Abstract

Objectives

The objective was to determine the frequency of trachoma genotypes of Chlamydia trachomatis-positive urogenital tract (UGT) specimens from remote areas of the Australian Northern Territory (NT).

Setting

The setting was analysis of remnants of C. trachomatis positive primarily UGT specimens obtained in the course of clinical practice. The specimens were obtained from two pathology service providers.

Participants

From 3356 C. trachomatis specimens collected during May 2012–April 2013, 439 were selected for genotyping, with a focus on specimens from postpubescent patients, in remote Aboriginal communities where ocular trachoma is potentially present.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of successfully genotyped UGT specimens that were trachoma genotypes. The secondary outcome measures were the distribution of genotypes, and the frequencies of different classes of specimens able to be genotyped.

Results

Zero of 217 successfully genotyped UGT specimens yielded trachoma genotypes (95% CI for frequency=0–0.017). For UGT specimens, the genotypes were E (41%), F (22%), D (21%) and K (7%), with J, H and G and mixed genotypes each at 1–4%. Four of the five genotyped eye swabs yielded trachoma genotype Ba, and the other genotype J. Two hundred twenty-two specimens (50.6%) were successfully genotyped. Urine specimens were less likely to be typable than vaginal swabs (p<0.0001).

Conclusions

Unlike in some other studies, in the remote NT, trachoma genotypes of C. trachomatis were not found circulating in UGT specimens from 2012 to 2013. Therefore, C. trachomatis genotypes in UGT specimens from young children can be informative as to whether the organism has been acquired through sexual contact. We suggest inclusion of C. trachomatis genotyping in guidelines examining the source of sexually transmitted infections in young children in areas where trachoma genotypes may continue to circulate, and continued surveillance of UGT C. trachomatis genotypes.

Keywords: SEXUAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study is highly targeted to a difficult problem in child protection, and the context and potential for translation is considered and discussed very carefully. Consistent with this, the authors included appropriate experts with extensive front line clinical and child protection experience.

It is the largest survey of genotypes of Chlamydia trachomatis from remote northern Australia.

The possibility that ocular genotypes were present in the urogenital specimens but below the detection level of the genotyping assay cannot be ruled out.

The failure rate of the genotyping assay meant that the power of the study was reduced somewhat.

Introduction

Chlamydia trachomatis causes ocular infections and sexually transmitted infections (STI) of the urogenital tract (UGT) in humans. Trachoma is a potentially blinding class of C. trachomatis disease with a characteristic pathology encompassing repeated infections leading to hypersensitivity, secondary bacterial infection, anatomical changes and consequent corneal scarring.1 The C. trachomatis strains associated with trachoma are distinct from other strains, which are primarily associated with UGT infections, but are also able to cause acute conjunctivitis (paratrachoma) that does not progress to the distinctive pathologies of trachoma. Trachoma is usually transmitted from child to child with ocular secretions, while paratrachoma is acquired by transmission from UGT infections, or as a result of mother to child transmission at delivery.2

The established basis for defining C. trachomatis strains is variation in the ompA gene, which encodes the immunodominant major outer membrane protein. OmpA genotypes A, B, Ba and C are associated with trachoma, genotypes D, E, F, G, H, Ia, J and K with non-invasive UGT infections and paratrachoma, and genotypes L1, L2, L2b and L3 with less common, invasive, lymphogranuloma venereum infections.2–4 The nomenclature reflects serology-based typing, although direct analysis of the ompA gene is now universally used.

When C. trachomatis is detected in UGT samples from a child, potential explanations are sexual abuse, autoinoculation from an ocular source, perinatal mother-to-child transmission, or contamination of specimens. Our research group has been investigating potential mechanisms leading to STI pathogen detection in UGT specimens, in the absence of sexual contact, in an endeavour to place numerical boundaries on their probabilities. For example, we have estimated the probability of the transfer of environmental STI pathogen-derived nucleic acid to diagnostic specimens.5 We demonstrated that while toilet-bathroom facilities in some Northern Territory (NT) primary health clinics were contaminated with nucleic acid from STI pathogens, the probability of this material finding its way into diagnostic specimens was low, but not zero. Therefore, it was recommended that UGT specimens from young children for STI testing should be obtained by trained staff in specialised facilities.

The current study addresses the issue of potential autoinoculation and/or infection of the UGT site with C. trachomatis derived from ocular C. trachomatis infection. This is particularly relevant to the remote regions of northern and Central Australia where trachoma remains endemic.6 7 Trachoma typically manifests as repeated childhood infections that are spread by the transfer of secretions from the eyes, usually in conditions of crowded living and poor hygiene. There are anecdotal reports that such secretions could contaminate the UGT, thus leading to detection of C. trachomatis in UGT specimens in the absence of sexual contact. While there are no published reports that clearly describe ocular to UGT transmission, or autoinoculation, it is well known that transmission from the UGT to the ocular site occurs in the setting of paratrachoma, and there is also evidence for transmission within families that could involve multiple modes.2 8 9

Our study addresses whether trachoma-associated ompA C. trachomatis genotypes are found in UGT diagnostic specimens from remote regions of the NT. If trachoma genotypes were very rare or undetectable in sexual transmission networks in the study area, then a trachoma genotype in a UGT sample from a young child would be unlikely to have been acquired from sexual transmission networks, and this is of potential significance in the child protection context.

Methods

We obtained deidentified C. trachomatis-positive diagnostic specimens that originated from the NT of Australia, and were collected between April 2012 and April 2013. Two pathology service providers, who at the time of this study accounted for the great majority of STI diagnostic testing in the NT, provided the specimens. Western Diagnostics Pathology (WDP) used the Aptima C. trachomatis diagnostic system (Hologic (Australia) Pty Ltd, Macquarie Park, New South Wales), and provided primary clinical samples as swabs and/or urine in the Aptima transport medium that had been prepared in accordance with the manufacturers of the Aptima system. The Royal Darwin Hospital (RDH) used the Siemens Versant C. trachomatis diagnostic system (Siemens Healthcare Australia, Bayswater, Victoria), and provided us with remnant purified total nucleic acid from clinical specimens. We contracted RDH to extract total nucleic acid from the Aptima swabs and urine specimens from WDP, using the extraction module of the Siemens Versant instrument, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The specimens were stored at 4°C for a period of up to 6 months, then at −80°C. Purified nucleic acid was stored at −80°C.

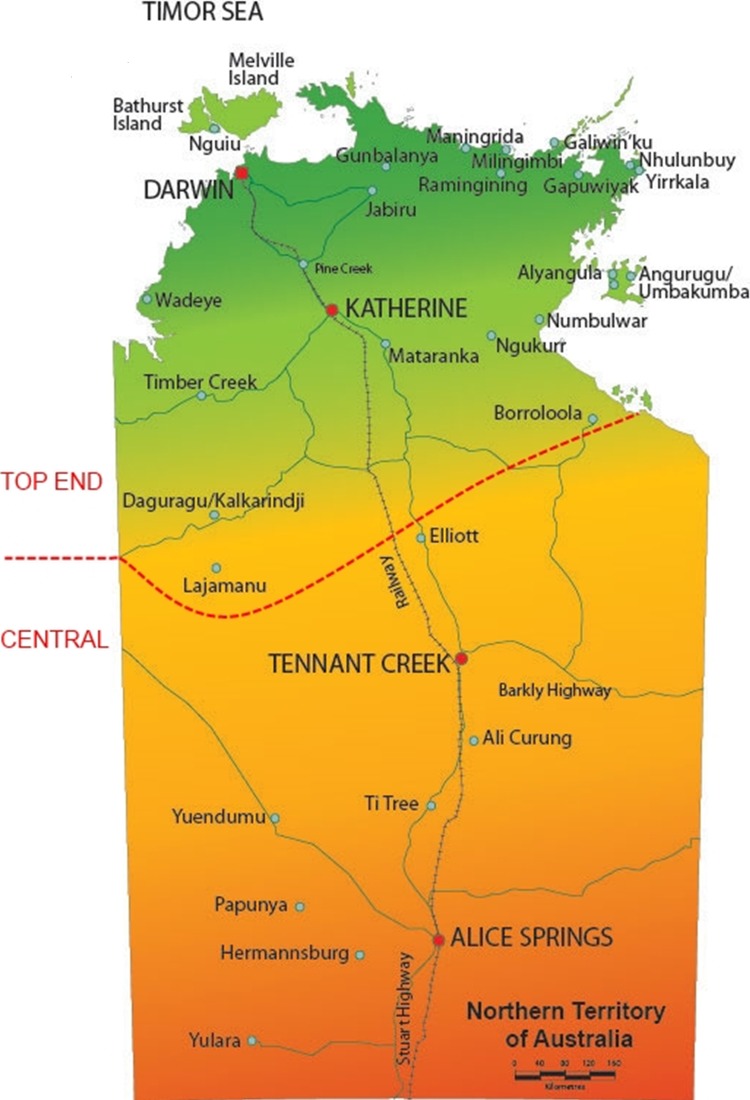

Our objective was to analyse specimens from remote indigenous communities. The great majority of such specimens were from WDP. Accordingly, we selected 434 specimens from the 2229 specimens available from WDP. These constituted 47% of the specimens from remote indigenous communities. They were selected on the basis of representing the geographical diversity and specimen type of the total collection. The specimens were classified as originating either from the Top End (260 specimens), or Central Australia (174 specimens) (figure 1). All the specimens were of UGT origin, except four eye swabs from the inland regions of the Top End. To this collection, we added three additional eye swabs from the inland regions of the Top End, and two UGT specimens from Central Australia from RDH, to yield a total of 439 specimens (263, Top End and 176, central Australia). This number was judged as sufficient to generate usefully narrow boundaries on the CI for the frequency of trachoma genotypes. The UGT specimens were primarily urine (75.4% of the Top End UGT specimens, 93.8% of central Australia UGT specimens). The other specimens were mostly lower vaginal swabs (LVS) (11.7% of Top End UGT specimens and 1.7% of Central Australia UGT specimens), with the remainder being other UGT swabs, or thin prep specimens. There were no rectal specimens. The breakdown of specimen types selected for analysis was similar to that for the entire collection from WDP; 70.2% urine specimens, 15.5% LVSs, with the remainder distributed between other UGT specimens and eye swabs. The ages were primarily adolescent and young adults, with only five specimens from patients <12 years old; 55.4% of the specimens were from female patients, 44.6% from male patients. The corresponding figures for the Top End and central specimens were 60.8% female, 39.2% male, and 47.2% female, 52.8% male, respectively.

Figure 1.

The Australian Northern Territory, with the boundary between the ‘Top End’ and ‘Central’ study areas indicated.

Following nucleic acid isolation, each sample was assessed for DNA quality using a quantitative PCR (qPCR) for a 260-bp fragment of the human β-globin gene,10 and specimens failing this step were not analysed further. The remaining nucleic acid preparations were analysed for C. trachomatis ompA genotypes using a two-stage method as described previously.4 This is based on hydrolysis probes, is performed on a qPCR platform, and supports the detection of multiple ompA variants in individual specimens. A limitation is that the closely related ompA genotypes B and Ba are not discriminated, so B/Ba genotypes were resolved by sequencing or high-resolution melting analysis (HRMA) of an ompA internal fragment amplified by PCR (see online supplementary figures S1 and S2).

Unless otherwise stated, the significances of differences in frequencies were assessed using the two-tailed Fisher's exact test.

Results

Genotyping was successful for 222 of the 439 specimens (50.6%), which included five of the seven eye swabs. Of the untypeable specimens, 28% yielded no signal in the β-globin gene PCR, 52% failed at the first stage of the genotyping, and 20% failed at the second stage of the genotyping. The LVS specimens were more likely to be typeable (29/33 (89%)) than urine specimens (165/358 (46%)) (p<0.0001); urine specimens from female patients were more likely to be typeable (93/169 (55%)) than those from male patients (72/189 (38%)) (p=0.0015); and male urine specimens from the Top End were more likely to be typeable (45/97 (46%)) than male urine specimens from Central Australia (27/92 (29%)) (p=0.0172). A breakdown of the typeability of different classes of specimens is provided as online supplementary data. We could find no relationship between length of storage and typeability (data not shown).

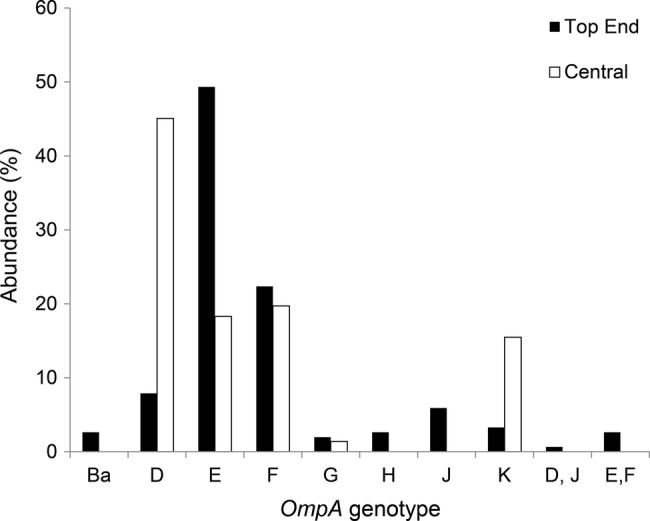

A single ompA genotype was detected in 212 UGT specimens and all five typeable eye swabs, and more than one ompA genotype was detected in five of the UGT specimens. Most importantly, no trachoma genotypes were identified in the UGT specimens (figure 2, table 1).

Figure 2.

The abundances of the ompA genotypes, in the samples obtained from the two study areas. All are UGT specimens except for the five eye swabs, which represent all four Top End genotype Ba specimens, and one Top End genotype J specimen. UGA, urogenital tract.

Table 1.

Chlamydia trachomatis genotypes in Australian studies, including the current study, relevant to remote regions of Australia, and/or reporting trachoma genotypes in non-ocular samples

| Study | Trachoma genotypes in UGT samples | Trachoma genotypes in ocular samples |

|---|---|---|

| This study | 0/217 | Ba×4 |

| Top End rural/remote, 1986–199111 12 | B×21/44 | B×54 Ba×13 C×31 |

| Western Australia remote13 | N/A | Ba×22 C×13 |

| NT remote14 | N/A | Ba×4 C×27 |

| Rural indigenous15 | 0/32 | N/A |

| Australian men who have sex with men15 | B×1/39 | N/A |

N/A, not applicable; UGA, urogenital tract.

The most common genotypes were D, E and F and K with genotypes G, H, J also present, but less common. The differences in the frequencies of genotypes D, E and F between the Top End and Central Australia were significant (χ2 p<0.0001), indicating that the C. trachomatis populations are not homogeneous across the NT. We could identify no correlations between genotype and age or gender (data not shown).

Four of the five typeable eye swabs were genotype B/Ba, according to the hydrolysis probe method, while the other was genotype J. HRMA revealed that all four B/Ba specimens were genotype Ba. PCR products from three of the latter specimens were sequenced, confirming genotype Ba. Three of the genotype Ba swabs were from prepubescent children, and the fourth was from an adult in late middle age, while the genotype J eye swab was from a young adult.

Discussion

Our objective is to inform the clinical and social response to the detection of C. trachomatis in UGT specimens in young children. Clinical guidelines frequently state that detection of an STI pathogen in a UGT sample is strongly indicative of sexual abuse and, even in the absence of a disclosure of sexual abuse, triggers an investigation by child protection and/or the justice system.16–20 This can be a difficult process because it is unlikely that the positive predictive value of a positive STI test for sexual contact is known with any accuracy for a young child, and both false positives and false negatives can be very problematic. In the NT in 2007, reports of high levels of child sexual abuse in remote Indigenous communities21 led to large-scale and contentious social interventions particularly on the part of the Australian Commonwealth Government. The high public profile of this issue, the imperatives to protect vulnerable members of the community, the remote locations, and well justified concerns regarding stereotyping of Aboriginal individuals, families and communities make this an exceptionally challenging area for service delivery.

In this study, the largest survey of ompA genotypes of C. trachomatis from remote Australia, of the 217 UGT specimens that were successfully genotyped, none yielded a trachoma genotype. This indicates that strains with trachoma genotypes are not currently contributing significantly to sexually transmitted C. trachomatis in the remote NT. The finding is similar to a previous smaller survey of C. trachomatis genotypes in UGT specimens in ‘rural’ regions of Australia15 (table 1). By contrast, four of the five genotyped eye swabs were trachoma genotype Ba, indicating that trachoma strains remain extant and associated with the ocular site.

Our results are relevant to the response when C. trachomatis is identified in UGT specimens in young children in remote regions of Australia, where trachoma strains of C. trachomatis continue to circulate. If there is no obvious evidence to account for the presence of C. trachomatis, such as disclosure of sexual contact, the strength of evidence for sexual contact is affected by the probability of autoinoculation of the UGT, or contamination of the specimen by trachoma strains of C. trachomatis. Our findings demonstrate that where C. trachomatis is identified in a UGT sample from a young child, genotyping of the C. trachomatis can be informative regarding inference of sexual contact or autoinoculation from an ocular site. The presence of an UGT genotype would represent stronger evidence of abuse on the basis of being consistent with acquisition from adult sexual networks. Conversely, identification of a trachoma genotype would constitute weaker evidence for acquisition from local adult sexual networks. As a result, in regions with endemic trachoma, genotyping should be incorporated into formal guidelines for the investigation of genital chlamydia in children.

A conservative approach to estimating the highest reasonable proportion of trachoma genotypes in UGT specimens in the study area is to determine the confidence limits on a frequency of 0/217. The upper boundary of the 95% CI is 0.017 (exact binomial method). While this directly provides insight into the probability that the C. trachomatis in a UGT sample has arisen from an ocular site, a more rigorous way to use that value would be to combine it with trachoma genotype frequencies in paediatric UGT specimens in the study area. An excess of trachoma genotypes in UGT specimens from children compared with UGT specimens from adults would define a lower boundary for the proportion of C. trachomatis-positive UGT specimens in children that cannot be accounted for by transmission from adult sexual networks. This, in turn, would enable the calculation of boundaries for pretest and post-test probabilities that the C. trachomatis in a paediatric sample arose from the ocular site.

It would be unwise to assume that the frequency of trachoma genotypes in adult UGT specimens in the study area is invariant. There are reports of trachoma genotypes in UGT specimens,22–28 and also in rectal specimens.15 Most commonly, if a trachoma genotype is identified in a survey of UGT specimens, then it is genotype B, and is in <5% of specimens. Most findings of genotype B in UGT specimens are from areas in which trachoma no longer exists, so it is likely that genotype B C. trachomatis, while usually classed as ‘trachoma’ strain, can be sexually transmitted in a sustainable manner. Specific examples of evidence for transmission of trachoma genotypes in sexual networks are a survey of 215 C. trachomatis-positive endocervical swab specimens from Japanese patients, of which one yielded genotype A, 11 genotype B, two genotype Ba, and one genotype C.28 Similarly, a survey of 50 urethral swabs and urine specimens from male patients in Greece yielded two genotype Bs,26 and similar studies in Finland in 1987 and 1996 yielded two genotype Bs from 51 specimens, and two genotype Bs from122 specimens, respectively.27 Particularly relevant to our results, and an outlier with respect to the proportion of UGT specimens containing trachoma strains, was a serotyping-based study performed in the remote north of the NT in the 1980s and 1990s.11 12 Forty-eight per cent of C. trachomatis-positive cervical swabs gave rise to serovar B isolates, while serovars B, Ba and C were identified in ocular swabs. Serovars Ba and C were not found in UGT specimens, with the possible exception of one specimen that also contained a urogenital serovar (table 1). It is significant that those specimens originated from a geographical area encompassed by the current study. Therefore, there is a case for ongoing surveillance of genotypes of C. trachomatis in the study area, with the objective of continually refining numerical boundaries for the frequencies of trachoma genotypes in adult and paediatric UGT specimens.

While the critical result in this current study is the lack of trachoma genotypes in UGT specimens, the results from the eye swabs are of interest and add to the understanding of the diversity of the C. trachomatis in the remote NT. Four of the five ocular specimens were genotype Ba. This is consistent with two previous studies of ocular C. trachomatis in remote Australia, which detected genotypes Ba and C,13 14 and the serotyping-based study described above in which serovars B, Ba and C were found in eye swabs11 12(table 1). The ages of the patients giving rise to the genotype Ba eye swabs are consistent with the association of this genotype and trachoma, while the age of the patient giving rise to the genotype J eye isolate is consistent with paratrachoma.

The proportion of specimens that were able to be successfully genotyped was lower than in another study using this assay.4 The reason is not fully understood. A contributing factor may have been that approximately half the specimens tested by Stevens and coworkers4 were anal swabs, and the other half were urine specimens, while the great majority of the specimens in the current study were urine. Urine specimens are known to have lower C. trachomatis loads than UGT swab specimens,29 30 and consistent with this, the LVS swabs in the current study were much more likely to be typeable than urine specimens. The lower typeability of urine from male patients compared with female patients, and for male urine from Central Australia compared with the Top End, remains unexplained. The storage of specimens in Aptima transport medium may have affected typeability. However, it has previously been shown that such storage does not preclude downstream genotyping,31 and in our study, the lack of correlation between time of storage at 4°C and typeability suggests that the RNA was not progressively degraded.

We considered whether the genotyping failure rate could bias the results. It is possible that specific instances of transfer to the UGT of C. trachomatis from an ocular source could result in very low levels of C. trachomatis in a corresponding UGT specimen and, therefore, compromise genotyping. However, our primary objective was to determine the genotypes circulating in the conventional sexual networks, rather than identification of specific instances of transfer of trachoma genotypes to the UGT. We cannot exclude the notion that trachoma genotypes are circulating in the sexual transmission networks, but never reaching the threshold for successful genotyping. However, we know of no reports that would support such a scenario. Therefore, we regard our study as credible in indicating which genotypes are circulating as STI pathogens in the study area, but with a potential limitation regarding the detection of specific instances of transfer to the UGT of C. trachomatis arising from ocular infections. It is likely that reliable genotyping of C. trachomatis in paediatric specimens in the context of child protection investigations will require careful sample collection, handling and transport for this very sensitive genotyping methodology, as has previously been suggested.5

In conclusion, we could not detect trachoma genotypes circulating in sexual transmission networks in the remote NT. Genotyping of C. trachomatis identified in UGT specimens from young children can, therefore, be informative in the context of child protection investigations. Trachoma genotypes should not be considered equivalent to UGT genotypes, and we suggest that inclusion of genotyping should be considered in guidelines and policies specifying institutional responses to STI diagnosis in young children in regions where ocular infections with trachoma strains may continue to exist. It is important that historical data from the study area and other studies worldwide, indicate that trachoma genotypes and, in particular, genotype B, can be transmitted through sexual networks, although is usually very uncommon if present at all. This suggests that ongoing genotyping of C. trachomatis in UGT diagnostic specimens could be of considerable value.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Terry Donald (forensic paediatrician), Frances McCann (sexual assault counsellor with Aboriginal cultural knowledge) and Carolyn Hudson (sexual assault counsellor with Aboriginal cultural knowledge) for providing comments on the manuscript. The authors thank Farshid Dakh and Rob Baird (Royal Darwin Hospital Pathology) for providing specimens and assisting with specimen management, and nucleic acid extractions. The authors thank Lida Ghoddosei for assistance with specimen handling. The authors thank Dr Louise Martin for discussions resulting in this research being initiated.

Footnotes

Contributors: PMG designed the study, analysed and interpreted results, and wrote the majority of the manuscript. NCB devised and implemented study protocols, selected specimens for analysis, and performed the bulk of specimen handling and initial data collection. SNT and SMG supervised the genotyping, assisted with the data interpretation, and provided expert editorial input. DCH contributed to the study design, and to specimen handling, and also checked and corrected the data analyses, and contributed to the development of the high-resolution melting analysis (HRMA) method. PA and RAL devised and implemented the HRMA method, and performed the PCR amplification and sequencing. SYCT contributed to the study design, assisted with development of data analysis methods and strategies, and provided expert editorial input. MK contributed to the development of the study protocols, supervised the collection and transport of specimens, and provided editorial input, particular as regards the use of APTIMA transport medium when non-standard genetic analyses are to be performed. PB, NR, TJ and GS contributed to the study design, and also provided expert editorial input, particularly as regards the potential of the results of the study to be translated into practice. TJ and GS were also central to the identification of the child protection issues that underpin this study. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council project grants 1004123 and 1060768. SYCT was supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship 1065736.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Human Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Territory epartment of Health and the Menzies School of Health Research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Taylor HR, ed. Trachoma: a blinding scourge from the Bronze age to the twenty-first century. VIC, Australia: Centre for Eye Research Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garland SM, Malatt A, Tabrizi S et al. . Chlamydia trachomatis conjunctivitis. Prevalence and association with genital tract infection Med J Aust 1995;162:363–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stothard DR, Jones RB. Chlamydia trachomatis omp1 genotyping J Infect Dis 2001;183:1542–3. 10.1086/320205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens MP, Twin J, Fairley CK et al. . Development and evaluation of an ompA quantitative real-time PCR assay for Chlamydia trachomatis serovar determination. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:2060–5. 10.1128/JCM.02308-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson P, Tong SY, Lilliebridge RA et al. . Multisite direct determination of the potential for environmental contamination of urine samples used for diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2014;3:189–96. 10.1093/jpids/pit085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor HR, Anjou MD. Trachoma in Australia: an update. Clin Exp Ophthamol 2013;41:508–12. 10.1111/ceo.12023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lange FD, Baunach E, McKenzie R et al. . Trachoma elimination in remote Indigenous Northern Territory communities: baseline health-promotion study. Aust J Prim Health 2014;20:34–40. 10.1071/PY12044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunlop EM, al-Hussaini MK, Freedman A et al. . Infection by TRIC agent and other members of the Bedsonia group; with a note on Reiter's disease. 3. Genital infection and disease of the eye. T Ophthalmol Soc UK 1966;86:321–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson C, Macdonald M, Sutherland S. A family cluster of Chlamydia trachomatis infection. BMJ 2001;322:1473–4. 10.1136/bmj.322.7300.1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saiki RK, Gelfand DH, Stoffel S et al. . Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science 1988;239:487–91. 10.1126/science.2448875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asche LV, Hutton SI. Serovars of C. trachomatis in northern Australia. In: Bowie WR, Caldwell HD, Jones RP et al., eds. Proceedings of the Seventh International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infections. International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infections; Harrison Hot Springs. Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douglas FP, Asche LV, Hutton SI. Serovars of C. trachomatis from the Northern Territory of Australia. In: Oriel D, Ridgway GL, Schachter J et al., eds. Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infections. International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infections Sanderstead, Surrey. Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porter M, Mak D, Chidlow G et al. . The molecular epidemiology of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infections in Western Australia: implications for trachoma control. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008;78:514–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens MP, Tabrizi SN, Muller R et al. . Characterization of Chlamydia trachomatis omp1 genotypes detected in eye swab samples from remote Australian communities. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42:2501–7. 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2501-2507.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandea CI, Debattista J, Joseph K et al. . Chlamydia trachomatis serovars among strains isolated from members of rural indigenous communities and urban populations in Australia J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:355–6. 10.1128/JCM.01493-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anonymous. Northern Territory Government. Reporting Child Sexual Harm. http://www.childrenandfamilies.nt.gov.au/library/scripts/objectifyMedia.aspx?file=pdf/55/75.pdf&siteID=5&str_title=Child%20Sex%20Abuse%20Flowchart.pdf (accessed Jun 2015).

- 17.Rogstad K, Thomas A, Williams O et al. . United Kingdom National Guideline on the Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Related Conditions in Children and Young People—2010. Secondary United Kingdom National Guideline on the Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Related Conditions in Children and Young People 2010. http://www.bashh.org/documents/2674.pdf (accessed Jun 2015).

- 18.Kellogg N. The evaluation of sexual abuse in children. Pediatrics 2005;116:506–12. 10.1542/peds.2005-1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammerschlag MR. Sexual assault and abuse of children. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53(Suppl 3):S103–9. 10.1093/cid/cir700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015;64:1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wild R, Anderson P. Ampe Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle, “Little Children are Sacred”. Report of the board of enquiry into the protection of Aboriginal children from sexual abuse 2007. http://www.inquirysaac.nt.gov.au/pdf/bipacsa_final_report.pdf (accessed Jun 2015).

- 22.Stothard DR, Boguslawski G, Jones RB. Phylogenetic analysis of the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein and examination of potential pathogenic determinants. Infect Immun 1998;66:3618–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gharsallah H, Frikha-Gargouri O, Sellami H et al. . Chlamydia trachomatis genovar distribution in clinical urogenital specimens from Tunisian patients: high prevalence of C. trachomatis genovar E and mixed infections BMC infect Dis 2012;12:333 10.1186/1471-2334-12-333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Machado AC, Bandea CI, Alves MF et al. . Distribution of Chlamydia trachomatis genovars among youths and adults in Brazil. J Med Microbiol 2011;60:472–6. 10.1099/jmm.0.026476-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han Y, Yin YP, Shi MQ et al. . Difference in distribution of Chlamydia trachomatis genotypes among different provinces: a pilot study from four provinces in China. Jpn J Inf Dis 2013;66:69–71. 10.7883/yoken.66.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Psarrakos P, Papadogeorgakis E, Sachse K et al. . Chlamydia trachomatis ompA genotypes in male patients with urethritis in Greece: conservation of the serovar distribution and evidence for mixed infections with Chlamydophila abortus Mol Cell Probes 2011;25:168–73. 10.1016/j.mcp.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niemi S, Hiltunen-Back E, Puolakkainen M. Chlamydia trachomatis genotypes and the Swedish new variant among urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis strains in Finland Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2011;2011:481890 10.1155/2011/481890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi S, Yamazaki T, Satoh K et al. . Longitudinal epidemiology of Chlamydia trachomatis serovars in female patients in Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis 2007;60:374–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiggins R, Graf S, Low N et al. . Real-time quantitative PCR to determine chlamydial load in men and women in a community setting. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47:1824–9. 10.1128/JCM.00005-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skidmore S, Horner P, Herring A et al. . Vulvovaginal-swab or first-catch urine specimen to detect Chlamydia trachomatis in women in a community setting? J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:4389–94. 10.1128/JCM.01060-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pabbaraju K, Wong S, Song JJ et al. . Utility of specimens positive for Neisseria gonorrhoeae by the Aptima Combo 2 assay for assessment of strain diversity and antibiotic resistance. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:4156–60. 10.1128/JCM.01694-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]