Abstract

Objectives

To explore the usefulness of Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) for general use by identifying best-evidenced formulae to calculate lean and fat mass, comparing these to historical gold standard data and comparing these results with machine-generated output. In addition, we explored how to best to adjust lean and fat estimates for height and how these overlapped with body mass index (BMI).

Design

Cross-sectional observational study within population representative cohort study.

Setting

Urban community, North East England

Participants

Sample of 506 mothers of children aged 7–8 years, mean age 36.3 years.

Methods

Participants were measured at a home visit using a portable height measure and leg-to-leg BIA machine (Tanita TBF-300MA).

Measures

Height, weight, bioelectrical impedance (BIA).

Outcome measures

Lean and fat mass calculated using best-evidenced published formulae as well as machine-calculated lean and fat mass data.

Results

Estimates of lean mass were similar to historical results using gold standard methods. When compared with the machine-generated values, there were wide limits of agreement for fat mass and a large relative bias for lean that varied with size. Lean and fat residuals adjusted for height differed little from indices of lean (or fat)/height2. Of 112 women with BMI >30 kg/m2, 100 (91%) also had high fat, but of the 16 with low BMI (<19 kg/m2) only 5 (31%) also had low fat.

Conclusions

Lean and fat mass calculated from BIA using published formulae produces plausible values and demonstrate good concordance between high BMI and high fat, but these differ substantially from the machine-generated values. Bioelectrical impedance can supply a robust and useful field measure of body composition, so long as the machine-generated output is not used.

Keywords: obesity, body fat, measurement

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Population-based cohort, but female only and restricted to parents.

Explicit, well-evidenced computational approach.

Validated against published gold standard data.

Compared with widely used commercial methods.

Introduction

The WHO defines obesity as “the disease in which excess body fat has accumulated to such an extent that health may be adversely affected”.1 Although prevention is the first step, being able to reliably identify people with excess fat is essential if the problem is to be recognised and appropriate measures taken. Body mass index (BMI) (weight/height2) is only an indirect measure of fatness, so reliable methods of assessing body composition are also needed. Hydrodensitometry is usually regarded as the nearest to a gold standard,2 but is impractical for most studies. For this reason, alternative less direct techniques have been developed. These include stable isotope methods and X-ray densitometry (DXA), but isotope methods require costly materials and processing while DXA equipment is non-portable. Thus, for ambulatory assessment, a cheaper and portable method such as Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) is valuable. The equipment necessary is portable, relatively inexpensive and the procedure simple and painless, making it a suitable method for studying large groups of participants.3 4 Measurements are taken by using four surface electrodes at different sites which send an imperceptible electrical current through the body (50 kHz alternating current of 800 μA between electrodes). Although there are also whole body machines, the most commonly used field method has been the four electrode leg-to-leg (eg, Tanita), where the participant stands with bare feet on the analyser’s footpads. The impedance value (Z) reflects the resistance and reactance that the electrical signal encounters when passing through the body; the ionised fluid in lean tissue acts as a conductor, and the current passes only through these fluids.4 The objective physical reading of impedance cannot be interpreted without further statistical manipulation, but assuming that LM∝TBW∝height2/Z, lean mass (LM) and total body water (TBW) can then be estimated, from which fat mass (FM) can be calculated.3 4

Although BIA is already widely used in practice and some body composition research, there remain doubts about its accuracy and precision.5 In fact, the measurement of impedance itself is reasonably precise and repeatable as long as it is performed in healthy individuals using the same method.6 However, the problems begin with the transformation of the impedance data. As described above, impedance has to be mathematically transformed to create meaningful estimates of TBW and thus LM. However, the prediction equations used to convert impedance measurements into measures of body fatness seem to vary between BIA machine manufacturers and incorporate elements other than the key components of height, impedance and the resistivity and hydration constants. Most manufacturers do not publish their formulae for commercial reasons, but the formulae used for a Tanita leg-to-leg machine have been published and these reveal that they incorporate weight as well as height2/Z.7 It is not clear what impact this would have on the results.

A further problem is that lean and FM values are difficult to interpret in isolation, as they differ systematically depending on the participant’s height,6 7 so in estimates of adiposity, FM is usually adjusted for body size by expressing it as a percentage of total mass. However, this then renders LM invisible, which is inappropriate, in individuals where LM varies markedly, since this will create differences in percentage fat (%fat), despite identical FM.6 This thus risks misclassifying individuals with low LM as having excess body fat and underestimating FM in very muscular individuals. It has been proposed as an alternative that lean and fat should simply be expressed as indices by dividing each by height2 6 but we have shown in children that this still leaves considerable unadjusted confounding by height.6 We have previously described an alternative approach in children which produces lean and fat residuals that fully adjust both lean and FM for height and compares them to a large population reference.6 8 We have now further applied these to children from the Gateshead Millennium cohort.9 As part of the same study, we wished to compare these children to similar measures collected in their parents, but there is no generally recognised method of doing this for adults.

Finally, it is widely believed in the lay population that BMI is a poor predictor of actually fatness. Published information on this suggests generally that BMI has high specificity, but low sensitivity to identify high %fat,10 but as described above, %fat may not be the best way to identify excess FM. We have already explored the concordance between BMI and fat residuals in children and found good concordance in the upper ranges of both, with very weak concordance for low BMI.11

We thus set out to:

Identify best-evidenced formulae to calculate lean and FM and compare these to historical gold standard data;

Compare these results with machine-generated output;

Explore how to best adjust estimates for height and how these overlap with BMI.

Participants and methods

Participants

The impedance data were obtained from mothers of participants in the Gateshead Millennium Study (GMS).12 This study set out to recruit all babies born to Gateshead residents between 1 June 1999 and 31 May 2000 in prespecified recruiting weeks. A wide range of information relating to feeding, growth and latterly obesity were collected on both children and parents and they have now been followed up to beyond age 9 years.12 The work presented here is based on data collected on the children's mothers in 2007, when the children were aged around 7 years. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Procedure

The data were collected on the children's parents at a home visit. While it was possible to study mothers at most of these visits, participation by fathers was minimal, so the paternal data were not used further. Impedance was measured using a single frequency (50 kHz) leg-to-leg BIA machine (Tanita TBF-300MA, Tokyo, Japan). The participants were measured wearing light clothing and bare feet after being asked to empty their bladders. The raw impedance and the machine calculated values for LM, FM and %fat were recorded. Height was measured without shoes and socks using a portable scale (Leicester height measure) to 0.1 cm with the head in the Frankfort plane. Weight was measured to 0.1 kg using the Tanita TBF-300MA. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2.

Analytical methods

The analysis was carried out using the software package R (V.2.2.0). We used the measured impedance to arrive at our own estimates of TBW and thus lean and FM using best published estimates of various constants. We assumed the hydration constant to be equal to 0.732 in adults, supported by previous studies13–15 which gives the equation LM=TBW/0.732. Values for the resistivity constant from various papers differ, but we used those of Bell,15 the only study where impedance was measured using leg-to-leg techniques. This gives a resistivity constant for adults ρ=0.66, that is, TBW=0.66 (height2/Z). Combining these two formulas, we obtained the following, simple prediction equation for adult women: LM=0.66/0.732 (height2/Z) or LM=0.898 (height2/Z). FM was then obtained as weight minus LM. To check whether the values we obtained for TBW, LM and FM using this approach were reasonable, we compared them to reference values from the two previous studies which had used gold standard measurement methods and published separate values for women.16 17 The first16 estimated TBW using 2H2O dilution, body density using underwater weighting and a three-component model to estimate %fat and LM. The second17 estimated TBW using either 2H2O or 3H2O dilution and FM and LM using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).

LM residual and FM residual

In order to produce estimates of FM and LM adjusted for height, a regression method to obtain lean and fat residuals for children8 was adapted to produce lean and fat residuals for their mothers, using their height as a covariate. A range of transformations of raw LM and raw FM were explored in order to achieve approximate normality and constant variance of residuals when regressed on height. The residuals from regression were then standardised (subtracting the mean and dividing by the SD) to get the so-called lean and fat standardised residuals. In addition, lean and fat indices were calculated (LM or FM divided by height2).

The Bland-Altman method18 was used to compare the Tanita-generated values of FM and LM and the ones produced following the equations presented in this paper. The Bland-Altman plot is widely used in the literature to evaluate the agreement between two methods that are measuring the same thing. This involves calculating the mean difference (bias) between the two measures for each individual and the limits of agreement. In addition, the difference is then plotted against the mean of the two measures, which supplies a visual presentation of how the spread and pattern of the points varies with the reading (variable bias). Linear regression was then used to test for a significant degree of variable bias.

Results

When the cohort was formed in 1999–2000, 1009 (81%) eligible mothers agreed to join the study and impedance and growth data were collected on 498 mothers in 2007, with mean (SD) age 36.3 (5.6) years (age range 23.6–53.1 years). Sixteen (3.2%) women were underweight (BMI <19), 141 women (28%) were overweight (BMI 25–30) and 112 (22%) were obese (BMI >30).

Total body water, lean mass and fat mass

Descriptive statistics for the anthropometric measurements are summarised in table 1. Values for TBW, LM, FM and %fat were produced according to the predictive equations discussed in the previous section. Summary statistics were then calculated using both this method and that of Tanita (table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the anthropometric measurements

| Median | IQR | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.63 | 32.25, 40.17 |

| Height (cm) | 163.00 | 158.90, 167.40 |

| Weight (kg) | 67.50 | 59.38, 78.20 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 80.40 | 74.20, 90.55 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 102.70 | 96.90, 111.30 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.06 | 22.64, 29.32 |

| Impedance (ohms) | 554 | 511, 600 |

| Generated using published constants |

Tanita-generated data |

Mean difference | p Value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |||

| TBW (L) | 31.8 | 29.0, 34.9 | NA | NA | ||

| LM (kg) | 43.4 | 39.6, 47.6 | 44.3 | 42.3, 47.4 | 1.19 | <0.001 |

| FM (kg) | 24.3 | 18.0, 33.5 | 23.0 | 17.1, 31.0 | −1.20 | <0.001 |

| %Fat | 36.0 | 30.4, 43.0 | 34.5 | 28.6, 39.9 | 1.97 | <0.001 |

*One sample t test.

%Fat, percentage fat; BMI, body mass index; FM, fat mass; LM, lean mass; NA, not available; TBW, total body water.

Our results are compared with the results from the two historical papers in table 2,16 17 with the GMS mothers stratified by age to allow direct comparability. Compared with the historical papers, the GMS values for weight BMI and %fat were much higher, with differences of the order of 1 SD in the youngest women. In contrast, the LM differed by no more than ¼ SD and were actually lower in the youngest GMS group.

Table 2.

Values (only females) reported by Hewitt 1993 and Chumlea 2001 (means±SD) compared with GMS values

| Study | Hewitt | Chumlea | GMS | Chumlea | GMS | Chumlea | GMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(year) | 32.6±6.0 | 20–29 | 23–29 | 30–39 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 40–50 |

| Year | 1993 | 2001 | 2007 | 2001 | 2007 | 2001 | 2007 |

| N | 19 | 124 | 75 | 130 | 292 | 104 | 128 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 59.6 | 8.0 | 62.4 | 12.4 | 68.7 | 16.9 | 63.6 | 13.7 | 71.9 | 17.2 | 68.5 | 15.5 | 69.7 | 13.0 |

| LM (kg) | 43.9 | 4.2 | 44.1 | 6.2 | 42.5 | 7.4 | 43.1 | 5.3 | 44.2 | 7.1 | 43.5 | 6.6 | 45.1 | 6.5 |

| %Fat | 26.0 | 5.4 | 28.5 | 8.8 | 36.6 | 9.1 | 30.4 | 8.2 | 37.1 | 9.3 | 35.0 | 8.9 | 34.2 | 9.0 |

| FM (kg) | * | * | 18.4 | 8.8 | 26.2 | 11.8 | 19.9 | 9.3 | 27.8 | 12.8 | 24.8 | 10.9 | 24.6 | 10.1 |

| BMI | * | * | 22.6 | 4.2 | 26.0 | 5.9 | 23.4 | 4.8 | 27.1 | 6.3 | 25.2 | 5.5 | 26.0 | 4.6 |

*Not described in that paper.

%Fat, percentage fat; BMI, body mass index; FM, fat mass; GMS, Gateshead Millennium Study; LM, lean mass.

Using our method, 22 (4%) women had fat <20%, and 180 (36%) had fat >40%. A majority of women with BMI >30 kg/m2 (88, 79%) also had greater than 40% fat, but only a minority of women with BMI <19 kg/m2 (4, 25%) had less than 20% fat.

How well do the manufactures algorithms describe body composition?

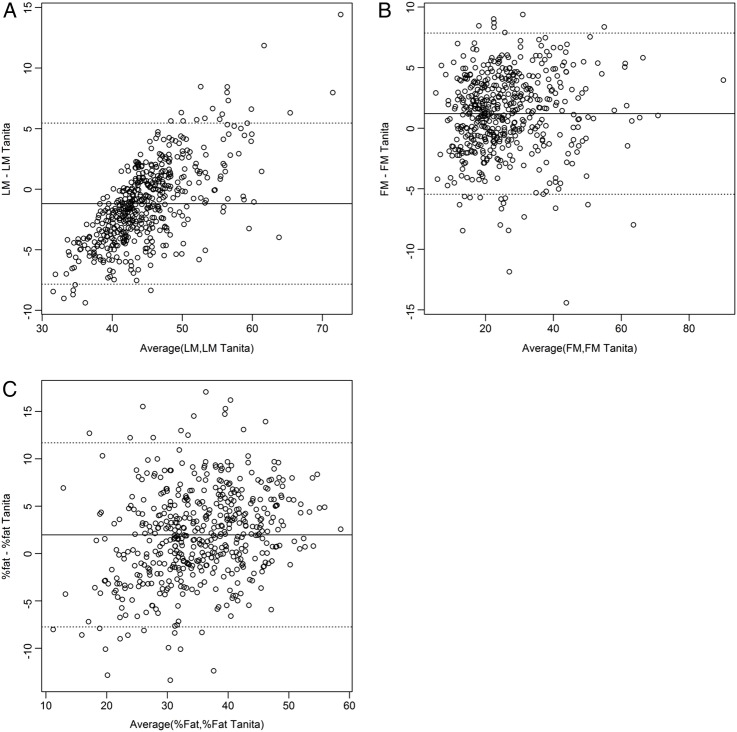

The machine-calculated values were also available for all but eight mothers. The sample mean of the Tanita LM values was lower than our calculated values (mean (SD) difference −1.19 (3.33) kg, 95% CI −1.49 to −0.90) while they were higher for FM and %fat (1.19 (3.33) kg, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.49 and 1.97 (4.86) %, 95% CI 1.54% to 2.40%, respectively). The two sets of results were compared using the Bland-Altman method,18 and major discrepancies were found between the two methods. The relative bias in LM calculated by Tanita varied from a mean of −4.68 for all participants in the lowest quintile for LM to +2.55 for the highest quintile (figure 1A). Using regression, this revealed a statistically significant slope (B=0.387 p<0.001). No equivalent relationship was seen for FM or %fat (figure 1B, C).

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman plots for (A) lean mass (LM), (B) fat mass (FM) and (C) percentage fat (%fat) comparing our own calculated values to the machine output values (Tanita).

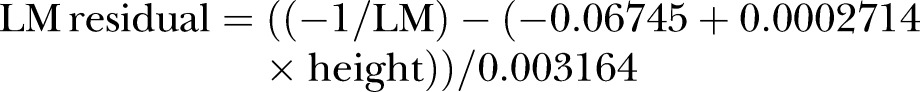

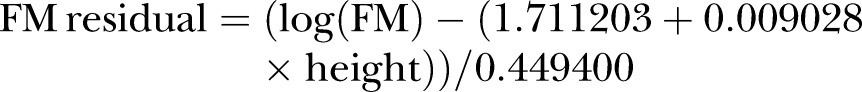

Calculation of lean residual and fat residual

In order to achieve approximate normality and constant variance of errors, LM was inverse-transformed before being regressed on height. The resulting equation was obtained:

|

1 |

Similarly, FM was log-transformed and regressed on height. The resulting equation was obtained:

|

2 |

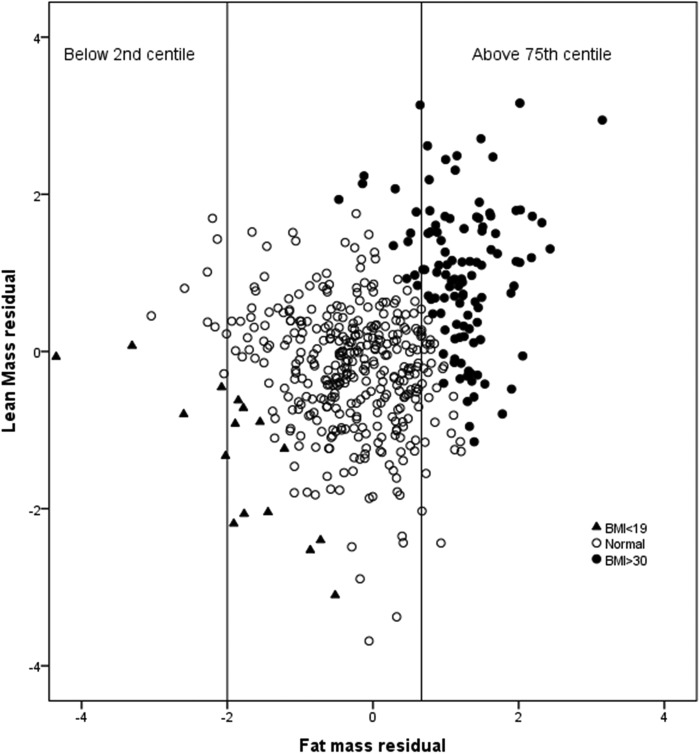

These residuals were normally distributed with mean 0 and variance 1. Fourteen women (2.4%) had fat residuals <−2 SD (roughly the 2.5th centile for the normal distribution) and 124 (25%) had fat residuals >0.68 SD (roughly the 75th centile) as expected.

Relationship of the FM and LM residuals to other measurements

As would be expected, there was no association between height and the lean and fat residuals (Spearman correlation (95% CI) of height with lean residual −0.02 (−0.11 to 0.07); with fat residual 0.01 (−0.07 to 0.10)), but nor was there any significant correlation of height with the lean index (LM/height2: −0.05 (−0.14 to 0.04)) or the fat index (FM/height2: −0.03 (−0.12 to 0.06)). Of the 112 women with BMI >30 kg/m2, 100 (91%) also had fat residuals >75th centile, while a BMI of >30 kg/m2 identified 81% of all with high fat residual. In contrast, of the 16 with BMI <19 kg/m2 only 5 (31%) also had fat residual <2nd centile (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of lean mass adjusted for height (lean mass residual) against fat mass adjusted for height (fat mass residual) per body mass index (BMI) category (underweight (<19) and obese (≥30). The vertical lines denote the cut-off for low (<2nd centile) and high (>75th centile) fat residual.

Discussion

In this analysis, we set out first to identify the best published constants to use for estimating lean and FM from BIA. The use of different devices and methods, under different conditions and on different populations, can make it difficult to extrapolate formulas from one study to another, but when we compared our estimated values for FM, LM and TBW to historical data, these revealed that results for LM were similar, while in contrast there were striking increases in average fat for the youngest, though not in the oldest category, who were already relatively more adipose even in the earlier cohorts.16 17 Overall, the participants had a high median %fat (34.5) and nearly a quarter had BMI in the obese range. The results thus vividly reflect the well-recognised secular trend to increased fatness in the population of young to middle-aged women. They also illustrate good concordance between high BMI and high adiposity.

Although based on a simplified mathematical model of the human body’s shape and composition, BIA has been shown to be a reliable method in population studies, though likely to have less accuracy in individuals.3 18 The large number of different published equations reflects differences in the reference methods, instrument used or the characteristics of the sample, but the constants used here seem to be the best ones currently in the public domain. The resulting prediction equation is strikingly simple in comparison to many others proposed in the literature, since it expresses LM as directly proportional to height2/Z with no involvement of other variables.

There are limitations to the study. We were not able to directly compare the results to a gold standard method and had to rely instead on published data. However, we were able to show how similar our results were to these, when using this simple parsimonious computational approach. The age range of the women was relatively narrow, but while there are major changes in body composition, hydration and body proportions during infancy and again in old age,16 in young adults body composition is fairly settled, making the model reported here valid for most adult women. We have data only on women as there were insufficient data on fathers in the GMS for useful analysis. The equations published here may well also be valid for use in men, but ideally this approach should also be extended in future, using a data set of adult men. While the hydration constant (relating TBW to LM) is fairly well established in adults, the resistivity constant (which relates impedance to TBW) was particularly difficult to find. A range of different values were found in the literature, but they were based on unusual samples,19 only males,13 20 or samples covering a wide age range.21 Only one study15 used the now more common leg-to-leg method and this is the value we used.

The results we obtained were very different from those automatically produced by the Tanita machine. It is important to understand the distinction between these essential mathematical transformation and factors that then correlate with or influence LM and FM, such as weight, sex and age. Manufacturers may seek to include these other variables in their output to contextualise their final estimates of adiposity. However, this then is no longer the true estimate of actual LM for that individual, derived solely from the impedance reading.

The equations used by different manufacturers and for different models are not made generally available, but have been published for a machine similar to the one used in our study.7 These show that the prediction equation used by Tanita for LM in adult women relies on weight as well as height2/Z and that the relative contribution of impedance to the final value is tiny relative to that of weight. For example, within our study, a decrease in impedance by 1SD (75 Ω) changes the Tanita-generated FFM estimate by <1 g while an increase in weight by 1SD (16 kg) increases it by 10% (2.8 kg). Thus, the machine estimate of FFM at least is actually largely based on weight rather than impedance.

Our results are in substantial agreement with the findings of Jebb et al,7 that Tanita underestimates LM in adult women by between 1 and 2 kg on average, and adds the new conclusion that the relative bias in the Tanita estimate of LM varies with size. The size of the positive biases in FM and %fat obtained using Tanita, relative to our method, are very similar to the bias relative to the four-compartment model reported in Jebb et al23 and our results also confirm poor agreement in individual cases.

Meanwhile, BIA technology has been moving on and there are now multifrequency devices and eight electrode techniques which aim to estimate different body segments and intracellular and extracellular fluids separately. However, the underpinning assumption and prediction formulae for these machines are likely to be even more complex and difficult to assess objectively.

We also considered the most robust way to adjust measures of fat and lean for height. A method that expresses lean and FM separately adjusted for height is much more informative than raw LM and FM estimates. We have shown previously in children that lean and fat residuals are effective in fully adjusting for height as well as allowing the data to be expressed as SD scores compared with a reference population.8 9 However, with adult women, simply dividing LM and FM by height2 also fully adjusted for height, suggesting that this would be equally valid and simpler. This adds further weight to Well's proposal22 that 1/Z could be used as a simple height-adjusted lean index, since lean index=LM/Ht2=(H2/Z)/Ht2=1/Z. Ideally, any reference should be validated against a more direct measure of body composition, but such studies seem only to have been done in children.

We have also shown that, as in children,11 the correspondence between high fat index and BMI is strong, with BMI >30 kg/m2 showing 90% specific and 80% sensitivity for fat index above the internal 75th centile. This is generally a much better correspondence than was found in a systematic review of the use of various BMI thresholds to detect high %fat measured, using different methods.10 However, most reviewed studies used much less stringent thresholds for both BMI and %fat, making comparison difficult.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that using BIA in models with published constants produces estimates of LM that are, on average, very similar to earlier studies using more direct methods, while the larger FM values are entirely plausible given the secular trends in obesity. These suggest that the physical measurement of impedance can produce useful estimates when appropriately transformed. However, the machine-generated estimates are likely to vary between machines and manufacturers and usually do not only reflect the physical measurement of impedance. They cannot therefore be used to validate or verify other measures of adiposity such as BMI. We would recommend that researchers using BIA in future should not rely on machine-generated estimates and should instead express lean and fat indices, divided by height2 in order to adjust for height.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the participation and advice of all those involved with The Gateshead Millennium Study—the research team, the families and children who took part, the External Reference Group, Gateshead Health NHS Foundation Trust, Gateshead Education Authority and local schools.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Gateshead Millennium Study core team: Ashley Adamson, Anne Dale, Robert Drewett, Ann Le Couteur, Paul McArdle, Kathryn Parkinson, John J Reilly.

Contributors: MSP and the Gateshead Millennium Study core team designed the research and supervised the data collection and data entry. MF-V analysed the data, performed the statistical analysis and initially drafted the paper. JHM and AS supervised the analysis and commented on successive drafts of the paper. CMW designed the research study, supervised the analysis, edited the paper and has primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Gateshead Millennium Study was first established with funding from the Henry Smith Charity and Sport Aiding Research in Kids (SPARKS) and followed up with grants from Gateshead NHS Trust R&D, Northern and Yorkshire NHS R&D, and Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Trust. This study wave was supported by a grant from the National Prevention Research Initiative (incorporating funding from British Heart Foundation; Cancer Research UK; Department of Health; Diabetes UK; Economic and Social Research Council; Food Standards Agency; Medical Research Council; Research and Development Office for the Northern Ireland Health and Social Services; Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health Directorates; Welsh Assembly Government and World Cancer Research Fund).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Gateshead Local Research Ethics Committee (LREC).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Ashley Adamson, Anne Dale, Robert Drewett, Ann Le Couteur, Paul McArdle, Kathryn Parkinson, and John J Reilly

References

- 1.[No authors listed]. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2000;894:i–xii, 1–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodie D, Moscrip V, Hutcheon R. Body composition measurement: a review of hydrodensitometry, anthropometry, and impedance methods. Nutrition 1998;14:296–310. 10.1016/S0899-9007(97)00474-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houtkooper LB, Lohman TG, Going SB et al. Why bioelectrical impedance analysis should be used for estimating adiposity. Am J Clin Nutr 1996;64(3 Suppl): 436S–48S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis—part I: review of principles and methods. Clin Nutr 2004;23:1226–43. 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker L, Reilly JJ, Slater C et al. Validity of six field and laboratory methods for measurement of body composition in boys. Obes Res 2003;11:852–8. 10.1038/oby.2003.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright CM, Sherriff A, Ward SC et al. Development of bioelectrical impedance-derived indices of fat and fat-free mass for assessment of nutritional status in childhood. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008;62:210–17. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jebb SA, Cole TJ, Doman D et al. Evaluation of the novel Tanita body-fat analyser to measure body composition by comparison with a four-compartment model. Br J Nutr 2000;83:115–22. 10.1017/S0007114500000155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherriff A, Wright CM, Reilly JJ et al. Age- and sex-standardised lean and fat indices derived from bioelectrical impedance analysis for ages 7–11 years: functional associations with cardio-respiratory fitness and grip strength. Br J Nutr 2009;101:1753–60. 10.1017/S0007114508135814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright CM, Cox KM, Sherriff A et al. To what extent do weight gain and eating avidity during infancy predict later adiposity? Public Health Nutr 2012;15:656–62. 10.1017/S1368980011002096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okorodudu DO, Jumean MF, Montori VM et al. Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:791–9. 10.1038/ijo.2010.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright CM, Garcia AL. Child undernutrition in affluent societies: what are we talking about? Proc Nutr Soc 2012;71:545–55. 10.1017/S0029665112000687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parkinson KN, Pearce MS, Dale A et al. Cohort profile: the Gateshead Millennium Study. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:308–17. 10.1093/ije/dyq015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukaski HC, Johnson PE, Bolonchuk WW et al. Assessment of fat-free mass using bioelectrical impedance measurements of the human body. Am J Clin Nutr 1985;41:810–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z, Deurenberg P, Wang W et al. Hydration of fat-free body mass: review and critique of a classic body-composition constant. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:833–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pace N, Rathbun EN. The body water and chemically combined nitrogen content in relation to fat content. J Biol Chem 1945;158:685–91. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hewitt MJ, Going SB, Williams DP et al. Hydration of the fat-free body mass in children and adults: implications for body composition assessment. Am J Physiol 1993;265(1 Pt 1):E88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chumlea WC, Guo SS, Zeller CM et al. Total body water reference values and prediction equations for adults. Kidney Int 2001;59:2250–8. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00741.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deurenberg P, Smit HE, Kusters CS. Is the bioelectrical impedance method suitable for epidemiological field studies? Eur J Clin Nutr 1989;43:647–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kushner RF, Schoeller DA. Estimation of total body water by bioelectrical impedance analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 1986;44:417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffer EC, Meador CK, Simpson DC. Correlation of whole-body impedance with total body water volume. J Appl Physiol 1969;27:531–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kushner RF, Schoeller DA, Fjeld CR et al. Is the impedance index (ht2/R) significant in predicting total body water? Am J Clin Nutr 1992;56:835–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells JC, Williams JE, Fewtrell M et al. A simplified approach to analysing bio-electrical impedance data in epidemiological surveys. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:507–14. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]