Abstract

Objectives

To explore perceptions of superslims packaging, including compact ‘lipstick’ packs, in line with 3 potential impacts identified within the impact assessment of the European Union (EU) Tobacco Products Directive: appeal, harm perceptions and the seriousness of warning of health risks.

Design

Qualitative focus group study.

Setting

Informal community venues in Scotland, UK.

Participants

75 female non-smokers and occasional smokers (age range 12–24).

Results

Compact ‘lipstick’-type superslims packs were perceived most positively and rated as most appealing. They were also viewed as less harmful than more standard sized cigarette packs because of their smaller size and likeness to cosmetics. Additionally, ‘lipstick’ packs were rated as less serious in terms of warning about the health risks associated with smoking, either because the small font size of the warnings was difficult to read or because the small pack size prevented the text on the warnings from being displayed properly. Bright pack colours and floral designs were also thought to detract from the health warning.

Conclusions

As superslims packs were found to increase appeal, mislead with respect to level of harm, and undermine the on-pack health warnings, this provides support for the decision to ban ‘lipstick’-style cigarette packs in the EU and has implications for policy elsewhere.

Keywords: Tobacco packaging, health warnings, superslims, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study allows an insight into how females respond to superslims packaging that is available in the UK and other markets.

This is the first study to explore the impact of superslims packaging on the seriousness of the pack in terms of warning of health risks.

Given the exploratory nature of the study and small sample size, the findings are not generalisable.

While young female perceptions of superslims packaging and warning messages are influenced by pack design, the study cannot say whether this would impact on smoking behaviour or brand choice.

Introduction

Historically, slim cigarettes have been marketed to young women via advertising campaigns communicating weight-control benefits, elegance, glamour, fashion and independence.1–3 However, as comprehensive bans on tobacco advertising have been introduced in many markets, tobacco companies are increasingly reliant on packaging related cues to communicate with consumers.

While global cigarette volumes are declining, superslims cigarettes are considered a major growth area.4 They now account for 5% of the European cigarette market,5 with growth in certain Middle Eastern markets6 and Central Asia.7 In many markets, superslims are available in different price segments.8 They are also available in different pack formats which include considerably smaller widths or depths than more regular shaped king-size cigarette packs. The most compact superslims pack format is often referred to as the ‘purse’ pack or ‘lipstick’ pack. Commonly used for brands associated with style, such as Vogue and Glamour, such packs are reported by tobacco companies as bringing ‘elegance and quality’ to the superslims sector.9 There has been concern, however, that such packaging may appeal to young women. That a recent tobacco industry journal states that “fashion statement cigarette formats such as Nanotek and Superslims could see further incidence amongst females”10 suggests that it may not only be existing female smokers that these products appeal to, but also non-smokers.

A number of recent studies have explored perceptions of ‘lipstick’-style superslims packaging. For instance, two separate qualitative studies found that a Silk Cut Superslims pack helped increase interest in the product among 15-year-old girls and women aged 18–24 years.11 12 In both studies, the smaller pack size and female-oriented colours communicated positive attributes and functionality. The pack was perceived as trendy, feminine and elegant, a convenient size for a handbag or a night out and was indicative of reduced harm. Furthermore, this style of packaging was found to generate feelings of cleanliness, niceness and femininity; positive emotions closely linked with a desired identity and image of young females.11 It was also frequently associated with items that gave them pleasure such as perfume, make-up and chocolate. The symbolic meanings inherent within slim pack designs therefore appear to help reduce negative connotations of smoking.

Experimental designs have found fully branded female-oriented superslims to be rated higher on appeal and taste and associated with more positive smoker traits than the same packs without descriptors, ‘plain’ packs and non-female brands.13–16 Compared with a regular king-size Silk Cut pack, the Silk Cut Superslims pack was perceived significantly more favourably by males and females aged 11–17 years on attractiveness, having a smoother taste and enticement to start smoking.17 It was also perceived to be of lower health risk and have less health warning impact than the king-size pack. Additionally, a cross-sectional survey with 11–16-year olds from across the UK found those receptive to the Silk Cut Superslims pack were 4.4 times more likely to be susceptible to smoking than those not receptive.18 These studies indicate the importance of pack structure on consumer responses. This is supported by a recent study with young women smokers and non-smokers (16–24 years), where pack structure was found to be more important than price, brand and warning size for ratings of product taste and harm and intention to try.19

Alongside the growing body of research, regulators have begun to take legislative action with respect to superslims. In Australia, the Plain Packaging Act 2011 requires the standardisation of pack appearance and also stipulates minimum pack dimensions, which effectively prohibits the small pack shapes which commonly distinguish superslims variants. Within the European Union (EU) the revised Tobacco Products Directive (TPD), to be implemented in all 28 EU member states from May 2016, will also ban lipstick-type packs. Unlike in Australia, the TPD sets minimum warning (rather than pack) dimensions; warnings must be a minimum height (44 mm) and width (52 mm). The Impact Assessment for the TPD states that “some of the current packet shapes make it difficult to effectively display health warnings…particularly the case for very narrow (including ‘lip-stick’ shaped) packets which distorts text and picture warnings”.20 The Impact Assessment also describes superslims packaging as increasing appeal and reducing perceived harm in comparison to other brand variants.20

In this study, we explored perceptions of superslims packaging, including compact ‘lipstick’ packs, in line with three potential impacts identified within the impact assessment of the TPD: appeal, harm perceptions and the seriousness of warning of health risks. We focused on adolescent girls and young adult women (12–24 years) given that the EU Commissioner for Health explained that lipstick-style cigarette packages are ‘specifically targeted to girls and young women’.21

Methods

Design and sample

Twelve focus groups were conducted with females aged 12–24 years (n=75) to explore perceptions of tobacco packaging, including female-oriented superslims packaging. Focus groups were considered an appropriate methodology as they provided an opportunity for participants to engage with one another and also the different styles of tobacco packaging. This helped to generate understanding of tobacco packaging from participants’ perspectives. Using purposive sampling, groups were segmented by age (12–14, 15–17, 18–24) and social grade (ABC1=middle class, C2DE=working class). ABC1 and C2DE groupings are based on the widely used UK demographic classifications system derived from the National Readership Survey. Social grade was determined by the chief income earner in the household. ABC1 social grade reflects managerial, administrative and professional occupations. C2DE reflects skilled and unskilled manual workers, and casual or lowest grade workers. The 15–17 and 18–24 age groups were also segmented by smoking status (non-smokers, occasional smokers). Difficulties in recruiting smokers in the youngest age group meant that the 12–14 groups comprised only non-smokers (see table 1).

Table 1.

Sample composition of focus groups: number, age, social grade and smoking status

| Group | Number | Age | Social grade | Smoking status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 15–17 | C2DE | Occasional |

| 2 | 6 | 15–17 | C2DE | Non-smokers |

| 3 | 6 | 18–24 | ABC1 | Occasional |

| 4 | 6 | 12–14 | ABC1 | Non-smokers |

| 5 | 7 | 15–17 | ABC1 | Non-smokers |

| 6 | 7 | 18–24 | ABC1 | Non-smokers |

| 7 | 6 | 12–14 | C2DE | Non-smokers |

| 8 | 6 | 12–14 | C2DE | Non-smokers |

| 9 | 6 | 12–14 | ABC1 | Non-smokers |

| 10 | 6 | 15–17 | ABC1 | Occasional |

| 11 | 6 | 18–24 | C2DE | Non-smokers |

| 12 | 7 | 18–24 | C2DE | Occasional |

Participants were recruited from Greater Glasgow in Scotland by independent professional market research recruiters. Potential participants were identified by recruiters through a combination of door knocking and street intercepts. For those who expressed an interest in participating, eligibility was assessed using a structured recruitment questionnaire. If they met the inclusion criteria, the recruiter provided participants with an information sheet outlining the research, what participation would involve and that it was voluntary. Participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. The recruiters obtained written informed consent from all participants and parental consent from those aged 12–17 prior to the start of the study. Participants received a small cash incentive for taking part.

Procedure

Groups were conducted in November/December 2013 in informal community venues in Greater Glasgow, and lasted approximately 90 min. The research team were responsible for conducting the groups and collecting the data. A lead moderator (AF) and assistant moderator conducted each group (CM/RP). A semistructured discussion guide was used to ensure that all topics of interest were explored while enabling flexibility, so that participants could express their views as part of an open discussion. As a warm-up exercise, participants were asked about shopping behaviour, before being shown a number of cigarette packs (n=23), with different colours, imagery and dimensions, to allow an insight into the types of pack designs available. The range of packs included more standard shaped king-size packaging, slims packaging and a range of superslims packaging including packs with a more standard width and very narrow ‘lipstick’-type packs. To facilitate discussion and explore reactions to the different packs, participants were asked to group them together as they thought appropriate. They were then asked to order the packs according to statements written on showcards: most appealing/least appealing; for someone like me/not for someone like me; pleasant taste/unpleasant taste; and least harmful/most harmful.

For the final exercise, 13 packs were removed and groups were asked to rate the remaining 10 packs in terms of seriousness in terms of warning about health risks (most serious/least serious; see figure 1). All exercises were accompanied by detailed probing and discussion of the reasons behind grouping and ordering decisions and the imagery associated with different pack styles. The discussions also explored perceptions of cigarette design.22 Data saturation was achieved within the 12 focus groups. All discussions were recorded on digital voice file with participants’ permission. Notes were also made throughout the discussions by the assistant moderator to record the ordering of packs for the exercises and any important participant responses. At the end of each group, participants were debriefed about the harms associated with tobacco use, the addictive nature of cigarettes, and that tobacco companies target young women with pack and cigarette design. Younger age groups (12–14 and 15–17 years) were also given an age appropriate take home pack including information on smoking-related harms and how tobacco marketing may promote smoking among youth.

Figure 1.

Packs used to explore seriousness in terms of warning about the health risks.

Analysis

Discussions were transcribed and checked for accuracy. Data were imported into NVivo V.10 to facilitate data management and analysis. Thematic analysis23 was used to identify emerging themes and transcripts were systematically coded into themes using a coding framework. Two members of the research team (RP, AF) coded the data, with coding decisions and labelling of themes discussed with the other members of the team (CM, AMM). Themes were compared and contrasted between different groups and different styles of packaging. All members of the team were involved in interpreting emerging findings. The analysis focused on whether there were differences in perceptions of superslims packaging, including ‘lipstick’ packs, comparative to perceptions of more standard shaped cigarette packaging.

Results

Pack perceptions and ratings were generally similar across groups, although where there are any differences between smoking status, social grade and age these are highlighted in the text.

Appeal

General appeal

Superslims packs in general were viewed as more appealing than other pack styles as they were described as ‘fancy’, ‘pretty’, ‘classy’ and ‘youthful’. They were considered unusual which made them stand out from other packs, which were described as ‘dull’, ‘bulky’ and ‘boring’ in comparison.

They [king-size packs] are not standing out to me as different or nice (Occasional smoker, 15–17).

The ‘lipstick’ superslims packs were viewed as most appealing in all groups. Unlike king-size and more standard shaped superslims packs they were described as ‘cute’ and referred to as ‘Barbie fags’ due to their small pack size and the perception of a toy-like appearance. These slimmer cigarette packs tapped into desired female traits such as femininity and glamour.

I would much rather have that [Glamour pack] than one of them [regular shaped pack] because that would make you feel like more kind of glamorous (Occasional smoker, 15–17).

Similarity to other products

The ‘lipstick’ superslims packs were repeatedly likened to a range of cosmetic products, such as perfume, lipstick, lip gloss and nail varnish, due to the pack imagery, for example, pastel colours and floral designs, and compact shapes. These associations heightened the appeal of these packs. In comparison, the less overtly feminine, king-size packs were congruent with their perception of what a cigarette pack looks like.

I just think it's much smaller [lipstick pack] and I just think it's more appealing to a woman because the pack, it does look like a lipstick (Occasional smoker, 15–17).

When first shown the ‘lipstick’ packs, some thought they were so similar to cosmetic products that they doubted whether they were genuine cigarette packs. For non-smoking groups, that these ‘pink’, ‘sparkly’ and ‘glamorous’ packs did not resemble conventional cigarette packs increased their appeal. As a result of their feminine design, the general view was that they would have greater stand out at point-of-sale than standard sized packs, tempting people to choose these packs over others. The design of the ‘lipstick’ packs was also thought to elicit curiosity among young children.

Children would be attracted to that, especially girls because I've got a little cousin and…she is always like “oh, can I have some lipstick” and like if she seen that she would be like “oh that's lipstick can I have that” (Non-smoker, 12–14).

Discretion

That superslims packs did not resemble traditional cigarette packs was considered an advantage for those who might wish to keep their smoking discreet. It was felt that this discretion could play a role in smoking uptake as superslims packs were considered particularly useful for concealing smoking. As the lipstick packs resembled cosmetic products, other people, such as parents and teachers, would be less aware that they were carrying cigarettes.

That's the kind of cigarette packet that you could have in your bag when you were younger and your parents would look through your bag and not even notice that as cigarettes. It's probably the most disguisable packet (Occasional smoker, 18–24).

[It could] encourage younger people to start smoking because they are not going to get caught (Non-smoker, 18–24).

Harm

The ‘lipstick’ packs were consistently rated as less harmful than more standard sized packs. This was attributed, in part, to the use of lighter and more feminine colours and patterns, where the ‘niceness’ of the pack reduced the image of a product that is damaging to health. In comparison, duller and darker colours, such greys and black, enhanced perceptions of harm.

They just look like they wouldn't hurt you and they wouldn't do anything to your insides because they look as if they've got flowers and that on them and like they are bright colours (Occasional smoker, 15–17).

You wouldn't look at that and think like that was something that would make your hands smell or like make your breath smell. It wouldn't be something that would like harm you (Occasional smoker, 15–17).

I think duller colours make you think it's bad for you (Non-smoker, 12–14).

Perceptions of harm were also linked to pack shape and size. The ‘lipstick’ superslims packs’ similarity to the compact packaging of cosmetic products reduced the association with tobacco and, concomitantly, the perception of harm. By comparison, standard sized packs, associated with more masculine traits, were perceived to be more harmful.

That one looks like a lip gloss, it looks as if it wouldn't do anything to you (Non-smoker, 15–17).

Cos they are bulkier packs as well, you think they'd be heavier and more dangerous (Non-smoker, 18–24).

Closely related to perceptions of harm was the user image of different styles of packaging. Superslims packaging was associated with young people and teenagers, a target group considered more likely to prefer a weaker and less harmful product. Standard sized, darker coloured packs fitted more closely with the image of an older (male) smoker. This user image was associated with health problems.

You have got in your head that it's like for an older person, you always see an old man coughing or whatever and they say they have been smoking for ages (Occasional smoker, 15–17).

Communicating the seriousness of health risks

A number of features contributed to how serious a pack was perceived in terms of communicating health risks, such as the pack graphics and structure, the font size of the health warning and the warning message.

Pack graphics (colour, pattern)

Pack colour influenced which packs were considered most and least serious about warning consumers about the health risks of smoking. Similar to perceptions of harm resulting from pack colour, darker colours communicated a more serious message while the brightly coloured, more feminine designs typical of superslims packs were felt to be ‘too pretty to be serious’. Bright colours and patterns also served as a distraction from the health warning.

Pack structure

The ‘lipstick’ packs were typically rated least serious in communicating the health risks of smoking due to their small size.

That one is really small and thin…You wouldn't think something like that [Glamour pack] could kill you (Non-smoker, 12–14).

Participants also commented that the very narrow shape of the Vogue pack altered the typography of the warning message. The message on this pack, with some words broken up with hyphens, reduced the seriousness and impact of the warning message. One participant commented that this made a joke out of the warning message, while another felt that the warning was not taken seriously by the manufacturer.

It just looks like a joke, the box, the packaging; it just doesn't look serious (Occasional smoker, 18–24).

It's as if they've not took it serious enough to write it properly, do you know what I mean? (Occasional smoker, 18–24)

Some participants commented that because the message looked ‘cluttered’ and ‘crammed’, it required more effort to read. Others thought that because the writing was disjointed, it indicated a brand from outside of the UK. Indeed, on first inspection, some participants initially thought the message was written in a foreign language.

Because it's broken up you wouldn't take the time to read it (Occasional smoker, 18–24).

It's the way it's written, it doesn't look like it's written in English (Non-smoker, 12–14).

It doesn't look like it's spelled right (Occasional smoker, 12–14).

Warning font size

Participants also commented on the smaller font sizes used for text warnings on the front of the narrow ‘lipstick’-type superslims packs. The font, described as ‘tiny’, was believed to undermine the seriousness of the warning in communicating health risk. The general view was that a smaller font did not stand out as much as a larger font, which would reduce the likelihood of people noticing or reading the message.

If they are wanting people to stop smoking they should have put the font size up bigger (Non-smoker, 18–24).

In comparison to the small font used on the ‘lipstick’ packs, the larger font used on the standard sized packs helped capture attention, and improve salience and readability.

It doesn't catch your eye whereas if you look at that [Sovereign pack] and you see the big ‘Smoking Kills’ it's kind of in your face (Occasional smoker, 18–24).

Because it says like ‘Smoking Kills’…people wouldn't stop to read that print on like the smaller, but that one [king-size pack] just stands out (Occasional smoker, 15–17).

Warning message

Of the two text warnings on the front of packs in the UK—‘Smoking Kills’ and ‘Smoking seriously harms you and others around you’—‘Smoking Kills’ was generally viewed as most serious in terms of communicating the health risks of smoking. This was due to the brevity, directness and perceived severity of the message.

‘Smoking Kills’ is more serious than ‘harming others’ (Non-smoker, 18–24).

Yeah because that is like the most, that's the message they are all trying to get across [Smoking kills] but that one is just saying it up front (Occasional smoker, 15–17).

Discussion

In the late 1990s, a marketing manager suggested that tobacco companies had much to learn from the cosmetics sector, given their expertise in targeting females through packaging design,24 with tobacco companies responding by introducing cosmetic-style packaging for superslims cigarettes. That superslims packaging reminded the adolescent girls and young adult women in this study of lipstick and perfume, items they considered pleasing, clearly helped to increase their appeal, as did the glamorous and feminine imagery evoked by these packs, which helped to reduce the negative associations that smoking has. This increased appeal of ‘lipstick’-style superslims packaging, in comparison to standard sized cigarette packaging, is consistent with past research.11–17 It is also consistent with the marketing literature, which suggests that pack shapes which are fun, convenient or easier to handle may appeal to children.25

Aside from appeal, we found that superslims packaging reduced perceptions of harm, as with previous studies11 12 17–19 and also research for other consumer products, such as confectionery, which is viewed as healthier when in smaller rather than larger packs.26 Tobacco companies have previously sought to communicate messages of reduced harm through the inclusion of filters in the 1950s,27 descriptors such as ‘light’ and ‘mild’,28 and the use of lighter pack colours, particularly for lower tar brands.29 It is possible that slimmer packaging is an extension of this trend.

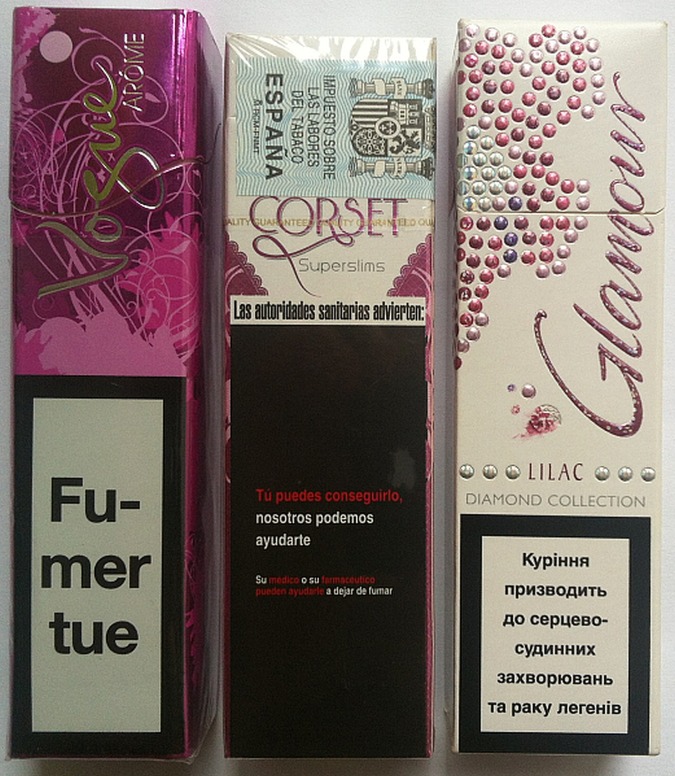

This study extends existing knowledge by also exploring the impact of superslims packaging on the seriousness of the pack in terms of warning of health risks. Marketers view packaging design as comprising two basic components: pack graphics and structure.30 In terms of graphics, the bright or pastel colours of superslims packaging, often adorned with floral imagery, was found to detract from the warning and reduce the impact of the seriousness of the message. With respect to the pack structure, the very narrow shape of the ‘lipstick’ packs clearly undermined the warning. As a result of the pack size, the font size of the warning message was much smaller than on regular packs, which made it less salient and less likely to be read. One of the packs, Vogue Frisson, which has recently been introduced to the UK market, is so small that some of the individual words on the warning message are unable to be displayed properly (eg, smok-ing and seri-ously). Some participants initially mistook the disjointed writing for a foreign language and others ridiculed it. Examples of these types of packs, with broken-up writing or small text, are evident throughout Europe (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Superslims packs with disjointed warning text or small font.

From May 2016, the new TPD is to be implemented across the EU. Tobacco companies oppose the Directive, and in November 2014 several tobacco companies won the right to challenge it before the European Court of Justice. The court will be asked to rule on whether the EU has misused its powers to legislate for tobacco, and whether its regulatory actions are disproportionate.31 The findings from this study suggest that the ban on ‘lipstick’-style superslims packaging, by way of stipulating minimum height, width and depth requirements for health warnings on packs, is proportionate. Aside from the impact of superslims packs in increasing appeal and reducing thoughts of harm, which is in keeping with earlier research, it would be difficult for tobacco companies to defend the disjointed warning messages or small font used on these packs.

In terms of limitations, given the small sample size, the findings are not generalisable to wider young female populations. While adolescent girls and young adult women's perceptions of superslims packaging and warning messages were influenced by design features such as colour, on-pack imagery, shape and typography, the study also gives no insight into whether this would impact on smoking behaviour or brand choice. Given that only non-smokers were recruited for the youngest age group (12–14 years), it would be useful to know what messages superslims packaging communicated to younger ages more involved in smoking. Understanding the appeal of packaging to even younger children, for example, 5–11-year olds, may also yield important insights. Children of this age residing with smokers are likely exposed to tobacco packaging. Exploring their perceptions of pack branding, colours and shapes may provide new understanding of how these things relate to children's perceptions of tobacco use. Experimental designs could also investigate further the impact of different pack shapes on warning salience or effectiveness.

This study supports existing evidence on ‘lipstick’-type superslims packaging by demonstrating that it influences perceptions of appeal and harm, and it extends it by showing how it reduces warning effectiveness. That these packs disrupt the warning message, create appeal and convey the illusion of reduced harm adds weight to the ban on compact superslims packs as a result of the TPD. As global sales of superslims continue to grow,4 and these packs can be found across the world, governments outside of the EU may like to consider if and how they choose to regulate these products. Further research outside of Europe and North America, where almost all research has been conducted, would be of significant value. Cigarette packaging is considered to have universal appeal32 and further studies would highlight the public health ramifications of tobacco packaging in other countries.

Footnotes

Contributors: CM conceptualised the study. AMM, AF and CM developed the topic guide. AF, CM and RP conducted the focus groups. AF and RP coded and analysed the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data. AF drafted and CM edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Cancer Research UK.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of Stirling Marketing Retail Division Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Barnewolt D, Thrane D. Review of imagery appealing to women smokers. Brown and Williamson, 1986. Bates No. 682121192/1203. https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=hgfm0132 (accessed 1 Jul 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. Factors influencing tobacco use among women. In: Women and smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001:453–536. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haglund M. Women and tobacco: a fatal attraction. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:563 10.2471/BLT.10.080747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meredith P. Back to the future—how patents have influenced filter innovation. Tob J Int 2015;1:75–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mapother J. Smoking kills—quit now. Tob J Int 2013;4:22–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Womack R. Middle East insights. Tob J Int 2014;2:62–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tobacco Reporter. From the plains. Tobacco Reporter, 2012;November:72–4.

- 8.Hedley D. Russia—a battleground under threat. Tob J Int 2014;1:32–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derbyshire D. Cigarette launch ‘targets girls’ with super-slim packs in female-friendly packaging. Daily Mail 20 October 2008. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1078862/Cigarette-launch-targets-girls-super-slim-packs-female-friendly-packaging.html (accessed 10 Aug 2015).

- 10.Lambat I. Tobacco remains a main component of China's five-year plan. Tob Int 2015;1:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford A, Moodie C, Mackintosh AM et al. . How children perceive tobacco packaging and possible benefits of plain packaging. Educ Health 2013;31:83–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moodie C, Ford A. Young adult smokers’ perceptions of cigarette pack innovation, pack colour and plain packaging. Australas Mark J 2011;19:174–80. 10.1016/j.ausmj.2011.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doxey J, Hammond D. Deadly in pink: the impact of cigarette packaging among young women. Tob Control 2011;20:353–60. 10.1136/tc.2010.038315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammond D, Doxey J, Daniel S et al. . Impact of female-oriented cigarette packaging in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:579–88. 10.1093/ntr/ntr045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammond D, Daniel S, White C. The effect of cigarette branding and plain packaging on female youth in the United Kingdom. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:151–7. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White CM, Hammond D, Thrasher JF et al. . The potential impact of plain packaging of cigarette products among Brazilian young women: an experimental study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:737 10.1186/1471-2458-12-737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammond D, White C, Anderson W et al. . The perceptions of UK youth of branded and standardized, ‘plain’ cigarette packaging. Eur J Public Health 2014;24:537–43. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford A, MacKintosh AM, Moodie C et al. . Cigarette pack design and adolescent smoking susceptibility: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003282 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotnowski K, Fong GT, Gallopel-Morvan K et al. . The impact of cigarette packaging design among young females in Canada: findings from a discrete choice experiment. Nicotine Tob Res 2015. Published Online First: 11 June 2015 10.1093/ntr/ntv114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Commission. Impact assessment. Proposal for a directive of the European parliament and of the council on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the member states concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products. Brussels: European Commission, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borg T. New Tobacco Products Directive: an achievement for public health in Europe. EU Newsletter 130, 2014. http://ec.europa.eu/health/newsletter/130/focus_newsletter_en.htm (accessed 10 Aug 2015).

- 22.Moodie C, Ford A, MacKintosh AM et al. . Are all cigarettes just the same? Female's perceptions of slim, coloured, aromatized and capsule cigarettes. Health Educ Res 2015;30:1–12. 10.1093/her/cyu063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Putz R. Learning from cosmetics. Tob J Int 15 June 1998;3:20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkes C. Food packaging: the medium is the message. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:297–9. 10.1017/S1368980009993168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wansink B, Park SB. At the movies: how external cues and perceived taste impact on consumption volume. Food Qual Preference 2001;12:69–74. 10.1016/S0950-3293(00)00031-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris B. The intractable cigarette ‘filter’ problem. Tob Control 2011;20(Suppl 1):i10–16. 10.1136/tc.2010.040113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mutti S, Hammond D, Borland R et al. . Beyond light and mild: cigarette brand descriptors and perceptions of risk in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction 2011;106:1166–75. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03402.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK et al. . The cigarette pack as image: New evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2002;11:i73–80. 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hine T. The total package: the evolution and secret meanings of boxes, bottles, cans, and tubes. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Co, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.BBC. Tobacco firms win legal right to challenge EU rules. BBC 3 November 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-29876574 (accessed 10 Aug 2015).

- 32.Thibodeau M, Martin J. Smoke gets in your eyes: branding and design in cigarette packaging. New York: Abbeville Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]