Abstract

Introduction

Despite the rising prevalence of stroke, no comprehensive model of postacute stroke care exists. Research on stroke has focused on acute care and early supported discharge, with less attention dedicated to longer term support in the community. Likewise, relatively little research has focused on long-term support for informal carers. This review aims to synthesise and appraise extant qualitative evidence on: (1) long-term healthcare needs of stroke survivors and informal carers, and (2) their experiences of primary care and community health services. The review will inform the development of a primary care model for stroke survivors and informal carers.

Methods and analysis

We will systematically search 4 databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL for published qualitative evidence on the needs and experiences of stroke survivors and informal carers of postacute care delivered by primary care and community health services. Additional searches of reference lists and citation indices will be conducted. The quality of articles will be assessed by 2 independent reviewers using a Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist. Disagreements will be resolved through discussion or third party adjudication. Meta-ethnography will be used to synthesise the literature based on first-order, second-order and third-order constructs. We will construct a theoretical model of stroke survivors’ and informal carers’ experiences of primary care and community health services.

Ethics and dissemination

The results of the systematic review will be disseminated via publication in a peer-reviewed journal and presented at a relevant conference. The study does not require ethical approval as no patient identifiable data will be used.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, COMMUNITY HEALTH SERVICES, LONG-TERM CARE, STROKE SURVIVORS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A synthesis of a large body of qualitative evidence on primary care services following stroke. On the basis of a preliminary selection of studies, we estimate that at least 50 studies will be included in the final review.

To the best of the knowledge of the authors, this is the first evidence synthesis of long-term care after stroke that focuses on primary care.

The review will assess how primary care meets the needs of informal carers as well as patients.

Long-term care provided by voluntary and private sectors will not be addressed in this review. Our focus is on how the prevalent population of stroke survivors and informal carers is supported by generalist services (ie, primary care and community health services delivered to general patient populations). In contrast, voluntary services such as the Stroke Association provide specialised services within the community, while the private sector will serve only a subpopulation of stroke survivors.

The review will not address long-term care experiences of stroke survivors living in nursing homes who have specific needs related to limited independence and greater severity of stroke.

Introduction

Stroke is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the UK, with one stroke occurring every 3 min and 27 s.1 The overall incidence of stroke has fallen by over 30% from 1.5/1000 person-years in 1999 to 1.0/1000 person-years in 2008. This has been attributed in part to improved identification of vascular risk factors and use of antihypertensive, lipid lowering and antiplatelet agents prior to, or after, stroke.2 In contrast, stroke prevalence has risen by 12.5% between 1999 and 2008, most likely resultant from greater survival rates and improved secondary prevention.2 The growing population of stroke survivors presents with diverse long-term needs which ought to be addressed. However, at present, no consistent model of long-term care beyond the discharge from specialist services has been developed in the UK.

Until recently, research and development of stroke services have focused mainly on acute care. Important advances have been made with regard to stroke unit care, thrombolysis and early supported discharge.3 However, there has been less development and evaluation of stroke services delivering postacute care. Surveys of stroke survivors have reported unmet needs following the discharge from specialist services in several domains, including mobility, continence care, communication, information provision, health provision after discharge and managing stroke-related problems.4 5 The multiple domains demonstrate the complexity of long-term postacute stroke care, and the potential need for interventions from many different types of healthcare and social care professionals. Less is known about the long-term outcomes of stroke survivors and informal carers following their transfer from hospital to primary care and the community services.

There is potential value in developing a comprehensive model of postacute stroke care to address the long-term unmet needs of stroke survivors and informal carers.3 6 The National Audit Office Report3 on improving stroke care has suggested that stroke survivors should be reviewed at 6 weeks and 6 months after stroke, and annually thereafter. However, little evidence to guide the development of such a long-term approach exists. For example, only 8% of the current UK National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke7 specifically address longer term stroke management. While there is an awareness of the need to address long-term management of stroke survivors and carers living in the community, there is little robust evidence on different approaches to support it.

Engaging informal carers in the process of postdischarge care is crucial, as over one-third of long-term stroke survivors are functionally dependent and 1 in 15 is cared for by their family and friends.1 Thus, informal carers act as mediators in the care pathway. Furthermore, informal carers as a group have unique needs associated with caring for a stroke survivor.8–14 A recent survey by the Stroke Association found that 64% of informal carers suffer from the emotional impact of stroke, over two-thirds experience stress and approximately 80% experience anxiety or frustration.15 Importantly, three quarters feel ill prepared for their role as a carer. Stress and negative affect can lead to a break in family relationships and abandonment of a caring role. Two-thirds of informal carers report experiencing difficulties in their relationship with a stroke survivor, and 1 in 10 breaks the relationship with their partner.15 Carer focused interventions which target problem-solving and coping can increase well-being and decrease the use of healthcare services.16 Therefore, supporting informal carers in their role is important and likely to form part of the primary care pathway. A number of quantitative and qualitative reviews explored the psychological consequences that caring for a stroke survivor has on informal (family) caregivers.9 12 16–18 However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no qualitative review has explored informal carers’ experiences of how primary care and community services support them in their caregiving role.

There has been a growing interest in recent years in postacute and long-term issues facing people with stroke and their informal carers.4 6 9 11 16 19 A number of qualitative studies into the long-term needs and experiences of primary care and community health services among stroke survivors and informal carers have been conducted.17 19–24 These studies can provide useful insights into the perceptions of primary care and community health services for stroke survivors and their informal carers. This protocol is a part of a programme module in developing a sustainable postacute care in primary care for stroke survivors and informal carers. The aim of this review is to synthesise and quality appraise qualitative evidence on stroke survivors, and informal carers’ needs and experiences of primary care and community health services after the discharge from specialist services. The review aims to inform how best to enable primary care services to provide long-term support to stroke survivors living in the community and informal carers.

Objective(s)

This review has the following objectives:

To identify, quality appraise and synthesise qualitative evidence on stroke survivors' and informal carers’ needs and experiences of primary care and community health services after discharge from specialist stroke care services.

To explore stroke survivors’ and informal carers’ views on the roles of primary and community care in providing services for stoke survivors and informal carers living in the community.

To construct hypotheses for the development of a primary care model which aims to provide sustainable long-term support for stroke survivors and informal carers in the community.

Review methods

Search strategy

The search strategy aims to identify all published studies from four databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsychINFO, supplemented by a review of reference lists and citation search. A search strategy will be developed on MEDLINE and adapted for other databases (the database for MEDLINE as in box 1). The search strategy will be based on the Information Specialists’ Sub-Group (ISSG) Search Filter strategy (http://www.york.ac.uk/issg-search-filters-resources/filters-to-identify-systematic-reviews), taking into account the inclusion of relevant subject headings (Medical Subject Heading, MeSH) and Boolean logic terms ‘OR’ and ‘AND’ in maintaining the sensitivity of the search strategy process. We will also refer to and update an earlier systematic review of the qualitative literature described by Murray et al.25 Primary search terms for subject headings will include; ‘stroke’, ‘CVA’, ‘stroke survivors’, ‘carers’, ‘primary care’, ‘homecare services’, ‘community health services’, ‘general practice’, ‘health services’, ‘general practitioner’, ‘family doctor’, ‘opinion’, ‘experience’, ‘satisfaction’, and ‘qualitative’, and will be adjusted accordingly throughout the search process.

Box 1. Search strategy for MEDLINE, March 2015.

1. Stroke

2. Stroke (title/abstract)

3. 1 Or 2

4. stroke[MeSH Terms]

5. CVA

6. cerebral stroke

7. ((stroke) OR Stroke[MeSH Terms]) OR CVA) OR cerebral stroke

8. patients or survivors or family or caregivers or carers

9. patients[MeSH Terms]

10. survivors[MeSH Terms]

11. family[MeSH Terms]

12. caregivers[MeSH Terms]

13. carers[MeSH Terms]

14. (12) OR 13

15. (9) OR 10

16. (11) OR 12

17. ((patients or survivors or family or caregivers or carers) OR 15) OR 16

18. general practice or family practice

19. private practitioner or general practitioner or family physician or family doctor

20. community health services

21. primary health care

22. homecare services

23. primary health care[MeSH Terms]

24. family physician[MeSH Terms]

25. general practitioner[MeSH Terms]

26. private practitioner[MeSH Terms]

27. family doctor[MeSH Terms]

28. community health services[MeSH Terms]

29. general practice[MeSH Terms]

30. family practice[MeSH Terms]

31. home care services[MeSH Terms]

32. (((community health services[MeSH Terms]) OR primary health care[MeSH Terms]) OR family physician[MeSH Terms]) AND home care services[MeSH Terms]

33. (((general practitioner[MeSH Terms]) OR family doctor[MeSH Terms]) OR general practice[MeSH Terms]) OR family practice[MeSH Terms]

34. 18 OR 19 OR 20 OR 21 OR 22

35. (32) OR 33) OR 34

36. perspective or experience or opinion or satisfaction or dissatisfaction or needs or demands

37. patient satisfaction or attitude or needs assessment

38. patient satisfaction[MeSH Terms]

39. attitude[MeSH Terms]

40. needs assessment[MeSH Terms]

41. (patient satisfaction[MeSH Terms] OR attitude[MeSH Terms]) OR needs assessment[MeSH Terms]

42. (37) OR 42

43. ((43) AND 35) AND 17) AND 3

44. qualitative OR focus group OR interviews

45. qualitative research

46. qualitative research[MeSH Terms]

47. evaluation studies as Topic[MeSH Terms]

48. focus groups[MeSH Terms]

49. ((((((qualitative) OR focus group) OR interviews)) OR qualitative research[MeSH Terms]) OR evaluation studies as Topic[MeSH Terms]) OR focus groups[MeSH Terms]

50. (44) AND 51

We will not place any date restriction. No restriction on language will be applied and attempts will be made to translate the publication to English for the analysis. Searching other resources will include conducting ‘related article’ searches in PubMed for all studies included in the review, contacting experts in the field, scanning reference lists of relevant studies, searching the reference lists of all included studies and key references, and searching for relevant papers that may have cited the included papers and key references in the ISI Web of Science (both the Science Citation Index and Social Science Citation Index).

Types of study

All studies published in peer-reviewed journals that use established qualitative methods of data collection (eg, interviews, focus groups, direct observations, action research or questionnaires that allow free text) will be included in the analysis.

The exclusion criteria include: (1) studies using quantitative or (2) mixed methods where the qualitative data cannot be separated, (3) studies of multiple patient populations (eg, traumatic brain injury, dementia, etc), (4) population of stroke survivors studied within an inpatient setting, (5) studies conducted within multiple settings (eg, hospital, early supported discharge, nursing homes, community setting) where perspectives on postacute services delivered in the community cannot be separated from other settings and (6) studies where data were collected using qualitative methods but analysed quantitatively. Conference abstracts and opinion pieces will not be considered.

Participants/populations

Participants will include: (1) adult (18 years or older) patients with a diagnosis of stroke living in the community and not under inpatient care; (2) informal adult (18 years or older) carers of stroke survivors living in the community and discharged from specialist services. Informal carers are defined as unpaid carers, including spouse or partner, family members, friends, or significant others who provide physical, practical, transportation or emotional help to someone after discharge from any stroke specialist service. No restrictions on the extent of caring role (eg, full-time or part-time carer, living in or visiting) will be imposed.

Intervention

The exposures of interest are: (1) primary care and (2) community health services, which support stroke survivors and informal carers after discharge from specialist services. We defined ‘primary care’, based on the definition used by Rashidian et al,26 as ‘the first level of contact with formal health services’, which provide first contact and ongoing care for patients with all types of health problems, including stroke. These include: family practice, general practice, outpatient settings and ambulatory care settings. Primary care may be delivered in the community or general practice settings, hence the inclusion of all these criteria during the search process.27

In contrast, our definition of ‘community health services’ includes services usually supplied by district nurses and allied healthcare professionals in the community such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy.28 Community health services can also include social services29 and psychological therapies (eg, counselling).

Outcome(s)

The outcomes of interest are qualitatively derived experiences, needs and preferences of stroke survivors and informal carers of primary care and community health services after discharge from specialist services. The secondary outcomes of this review are the views of stroke survivors and informal carers on the roles of primary care in providing them with relevant services after discharge from specialist care.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of the studies

Search results will be entered into Endnote folders. A three-stage screening process will be applied. The first stage will involve assessing the titles and abstracts, in which clearly irrelevant titles will be excluded. The second stage will involve abstract screening, and the third full-text screening. Two reviewers will independently perform the search, and later meet to compare the results. Studies can be excluded at any stage if both reviewers are in consensus but if there is no consensus on the selected title/abstract, full-text screening will be performed. During full-text screening, consensus must be reached to include or exclude studies for the review. A third reviewer will be engaged to make a final consensus if required. Where appropriate, we will contact the study authors for further information.

Data extraction and management

Data from included studies will be recorded on a purpose-built data extraction form. Descriptive data will include sample size, recruitment method, study design, study objectives, patient characteristics, methods of data collection, data analysis, recorded outcomes, themes, key findings, limitations and conflict of interests, which will be reported in a table including the referencing details.

We will also collect data on the types of health and care services (especially the primary care services) in order to develop a map of health and care services. This will help us to understand the associations between the needs and perceptions of the patients with stroke and informal carers with the types of services received after their discharge. We will extract and document additional information concerning the first/contact author's name, year of publication, language, country of study and study setting. A pilot trial of the data extraction form on the first few papers will be conducted to assess its adequacy, and changes will be made if necessary. Two independent reviewers will conduct the review of relevant articles to extract pertinent details identified from the form. Disagreement will be resolved by discussions until consensus was reached. All information will be stored in a database (QSR International NVivo software30).

Quality appraisal

Views on whether included studies should be rigorously appraised purely on the quality rather than conceptual contribution have been debated extensively.31 32 Since this review is an exploratory exercise for the development of a primary care model of stroke care, we chose to take a pragmatic approach to critical appraisal of included studies. We will include all studies that meet the inclusion criteria irrespective of the study quality, but will apply two appraisal tools.

First, all included studies will be scored using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP)33 quality assessment tool as the checklist for qualitative studies. This tool was chosen as it allows rapid evaluation using a 10-item checklist. The checklist can be applied to different types of qualitative designs to assess credibility, transferability, dependability and conformability of the studies. Second, articles will be evaluated using criteria outlined by Dixon-Woods et al,34 according to their relevance to our research objectives. Included studies will be scored as KP (a ‘key paper’ that is conceptually rich and could potentially make an important input to the synthesis); SAT (a ‘satisfactory paper’ of when the value or relevance of the paper to synthesis is unclear); IRR (a paper considered ‘irrelevant’ to the synthesis) or FF (a paper considered ‘fatally flawed’ methodologically). Two reviewers will perform the quality appraisal assessment independently. We will use both scoring methods and discussion in order to arrive at a consensus on quality. A third reviewer will make the final consensus should no agreement be reached between the two reviewers.

In this review, the quality appraisal process is not to exclude any studies but to provide further understanding of the contributions of the included studies at a later stage of this review. This will be used to find a balance between the relevance of insights and methodological flaws, as methodologically weak studies may offer insights that are new and not presented in the methodologically strong studies. Following the completion of the synthesis, the results will be analysed to examine which concepts have been derived from which papers. The development of concepts will be linked to the original papers in the light of their quality assessment.31

Data synthesis and analysis

For the synthesis, we will use the meta-ethnographical approach first described by Noblit and Hare,35 and subsequently modified for use in health services research, including for similar reviews such as by Rashid et al.36 This approach focuses on the ‘translation of qualitative studies into one another’ with the objective of developing interpretations and conceptual insights, rather than simply aggregating studies as occurs in a number of other approaches to synthesising findings from qualitative studies.

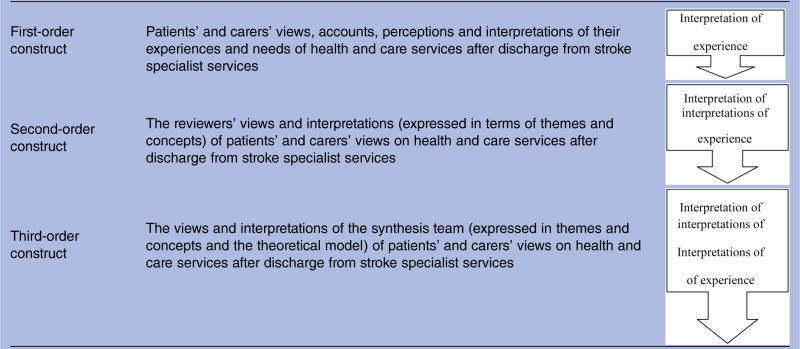

Meta-ethnography involves a three-stage approach (as in table 1): determining the key concepts from each article, known as first-order construct; translating the first order constructs across articles to determine second-order constructs; and synthesising these second-order constructs to produce overarching concepts, or third-order constructs. The first stage will involve two reviewers reading and rereading the included studies in chronological order, making note of stroke survivors’ and informal carers’ views, accounts and interpretations of their experiences of primary care and community health services after discharge from specialist services, and the authors’ interpretation of these constructs. Each will summarise the authors’ original findings using terms and key concepts from the paper, and the first-order constructs will be agreed on by consensus.

Table 1.

Working definition of first-order, second-order and third-order constructs (taken from Malpass et al31 drawing on work from Noblit and Hare35)

|

Reprinted from Social Science & Medicine. Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D, et al. “Medication career” or “Moral career”? The two sides of managing antidepressants: A meta-ethnography of patients' experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:154–68.31 Copyright (2015), with permission from Elsevier (www.journals.elsevier.com/social-science-and-medicine).

The ‘second-order constructs’ will be developed by completing a grid table of first order constructs from each study/article in Microsoft Excel; resultant second-order constructs will be agreed on at further consensus meetings. These second-order constructs will then be used as building blocks for the ‘line or argument’ synthesis which interprets the relationship between them, developing third-order constructs to create an overarching theoretical framework representing a further level of conceptual development incorporating all the included studies.35 36 We will achieve this by using discussions and consensus meetings of the team members. We will analyse the relation between findings of individual studies in two possible ways: (1) reciprocal, where the concepts in studies overlap; and (2) refutational, where the concepts in studies are in conflict. The final stage will involve constructing the ‘line of argument synthesis’, in which we will create a theoretical model to describe how the overall findings inform what might be sustainable long-term support in primary care. NVivo Software30 and hard copies will be used during the data synthesis and analysis processes and comparison will be made between the two entries to maintain robustness of the process.

Discussion

Unlike for acute stroke care, there is no agreed model as to how to provide long-term care and support for people with stroke and, in particular, how to engage primary care with this process. Until recently, there was a lack of consensus on how best postacute and long-term stroke care should be delivered. Service development and research in the community have focused on prevention and early intervention.37 Studies looking at longer term stroke, especially into health needs and service provision to stroke survivors living in the community, were few, with small patient numbers and heterogeneous in nature. Although a number of studies have addressed long-term psychological outcomes after stroke, they have mostly recruited stroke survivors in the first year after stroke, and so reflect the needs of incident rather than prevalent stroke survivors.38–40 In contrast, studies addressing the experiences of care provision for long-term needs after stroke in the general population of stroke survivors are sparse. Hence, with the increasing prevalence of stroke in the UK,2 there are real challenges in delivering sustainable long-term stroke support after specialist discharge. Earlier studies have identified the role of primary care services as the first point of contact between healthcare providers and stroke survivors in the community.25 41 For a comprehensive model of long-term stroke care to be developed, it is important to have an understanding of the perceptions of stroke survivors and informal carers of what is needed beyond specialist services. This systematic review will collate qualitative research to provide a better understanding of stroke survivors’ and informal carers’ perceptions in order to inform the development of a primary care model for long-term stroke care in the community.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Lisa Lim, Viona Rundell, Victoria Hobbs.

Contributors: NAA wrote the study protocol with input from the coauthors. NAA, DMP, RM and JM are the team members for the study project. DMP and NAA revised the manuscript on peer review. NAA, DMP, RM and JM were involved in the design of the protocol. FMW was involved in the design and methodology of the study protocol. All the authors critically reviewed the manuscript, its subsequent revisions and have given final approval to this version.

Funding: National Institute for Health Research (PTC-RP-PG-0213-20001).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We will comply with the standard data sharing policy of this journal.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Lisa Lim, Viona Rundell, and Victoria Hobbs

References

- 1.Stroke Association. State of the nation stroke statistics. 2015. https://www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/stroke_statistics_2015.pdf

- 2.Lee S, Shafe ACE, Cowie MR. UK stroke incidence, mortality and cardiovascular risk management 1999–2008: time-trend analysis from the General Practice Research Database. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000269 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Audit Office. Progress in improving stroke care. Department of Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKevitt C, Fudge N, Redfern J et al. . Self-reported long-term needs after stroke. Stroke 2011;42:1398–403. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.598839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray J, Young J, Forster A et al. . Feasibility study of a primary care-based model for stroke aftercare. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:775–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mold F, Wolfe C, McKevitt C. Falling through the net of stroke care. Health Soc Care Community 2006;14:349–56. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00630.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. National Clinical Guideline for Stroke. 4th edn London: Royal College of Physicians, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brereton L, Carroll C, Barnston S. Interventions for adult family carers of people who have had a stroke: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil 2007;21:867–84. 10.1177/0269215507078313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaugler JE. The longitudinal ramifications of stroke caregiving: a systematic review. Rehabil Psychol 2010;55:108–25. 10.1037/a0019023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenwood N, Mackenzie A, Harris R et al. . Perceptions of the role of general practice and practical support measures for carers of stroke survivors: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:57 10.1186/1471-2296-12-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGurk R, Kneebone II. The problems faced by informal carers to people with aphasia after stroke: a literature review. Aphasiology 2013;27:765–83. 10.1080/02687038.2013.772292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rombough RE, Howse EL, Bagg SD et al. . A comparison of studies on the quality of life of primary caregivers of stroke survivors: a systematic review of the literature. Top Stroke Rehabil 2007;14:69–79. 10.1310/tsr1403-69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salter K, Zettler L, Foley N et al. . Impact of caring for individuals with stroke on perceived physical health of informal caregivers. Disabil Rehabil 2010;32:273–81. 10.3109/09638280903114394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White CL, Lauzon S, Yaffe MJ et al. . Toward a model of quality of life for family caregivers of stroke survivors. Qual Life Res 2004;13:625–38. 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021312.37592.4f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroke Association. Feeling overwhelmed. The emotional impact of stroke. Stroke Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng HY, Chair SY, Chau JP-C. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for stroke family caregivers and stroke survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns 2014;95:30–44. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenwood N, Mackenzie A, Cloud GC et al. . Informal primary carers of stroke survivors living at home-challenges, satisfactions and coping: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Disabil Rehabil 2009;31:337–51. 10.1080/09638280802051721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saban KL, Sherwood PR, DeVon HA et al. . Measures of psychological stress and physical health in family caregivers of stroke survivors: a literature review. J Neurosci Nurs 2010;42:128–38. 10.1097/JNN.0b013e3181d4a3ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray J, Ashworth R, Forster A et al. . Developing a primary care-based stroke service: a review of the qualitative literature. Br J Gen Pract 2003;53:137–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allison R, Evans PH, Kilbride C et al. . Secondary prevention of stroke: using the experiences of patients and carers to inform the development of an educational resource. Fam Pract 2008;25:355–61. 10.1093/fampra/cmn048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameron J, Naglie G, Gignac M. Examining the changing needs of stroke family caregivers. Stroke 2010;41:e492. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cameron JI, Naglie G, Silver FL et al. . Stroke family caregivers’ support needs change across the care continuum: a qualitative study using the timing it right framework. Disabil Rehabil 2013;35:315–24. 10.3109/09638288.2012.691937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dowswell G, Lawler J, Dowswell T et al. . Investigating recovery from stroke: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 2000;9:507–15. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2000.00411.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reed MC, Harrington R, Wood VA. Stroke survivors’ long-term needs in the community: a meta-analysis of qualitative literature. Int J Stroke 2009;4:26 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00309.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray J, Young J, Forster A et al. . Developing a primary care-based stroke model: the prevalence of longer-term problems experienced by patients and carers. Br J Gen Pract 2003;53:803–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rashidian A, Shakibazadeh E, Karimi- Shahanjarini A et al. . Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of doctor-nurse substitution strategies in primary care: qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiley-Exley E. Evaluations of community mental health care in low- and middle-income countries: a 10-year review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:1231–41. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foot C, Sonola L, Bennett L et al. . Managing quality in community health care services. London: The King's Fund, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrews GR, Faulkner D, Andrews M et al. . A glossary of terms for community health care and services for older persons. 2004. http://www.who.int/kobe_centre/ageing/ahp_vol5_glossary.pdf

- 30.NVivo qualitative data analysis software [program]. 10 version: QSR International Pty Ltd, 2015.

- 31.Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D et al. . “Medication career” or “Moral career”? The two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:154–68. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith LK, Pope C, Botha JL. Patients’ help-seeking experiences and delay in cancer presentation: a qualitative synthesis. Lancet 2005;366:825–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67030-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Research Checklist. Secondary: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Research Checklist 2013. http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf

- 34.Dixon-Woods M, Sutton A, Shaw R et al. . Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12:42–7. 10.1258/135581907779497486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noblit GW, Hare RW. Meta-ethnography: synthesising qualitative studies. Qualitative research method. London: SAGE Publications, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rashid MA, Edwards D, Walter FM et al. . Medication taking in coronary artery disease: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:224–32. 10.1370/afm.1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aziz N. Long-term rehabilitation after stroke: where do we go from here? Rev Clin Gerontol 2010;20:239–45. 10.1017/S0959259810000080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hackett Maree L, Anderson Craig S, House A et al. . Interventions for preventing depression after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(3):CD003689. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003689.pub3/abstract. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/14651858.CD003689.pub3/asset/CD003689.pdf?v=1&t=ia6tue4n&s=e07bd9f188b83b8c4abd88a70411a8427a6ae9e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farner L, Wagle J, Engedal K et al. . Depressive symptoms in stroke patients: a 13 month follow-up study of patients referred to a rehabilitation unit. J Affect Disord 2010;127:211–18. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell Burton CA, Holmes J, Murray J et al. . Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(12):CD008860 10.1002/14651858.CD008860.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hare R, Rogers H, Lester H et al. . What do stroke patients and their carers want from community services? Fam Pract 2006;23:131–6. 10.1093/fampra/cmi098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]