Abstract

Objectives

Duhuo Jisheng decoction (DJD) is considered beneficial for controlling knee osteoarthritis (KOA)-related symptoms in some Asian countries. This review compiles the evidence from randomised clinical trials and quantifies the effects of DJD on KOA.

Designs

7 online databases were investigated up to 12 October 2015. Randomised clinical trials investigating treatment of KOA for which DJD was used either as a monotherapy or in combination with conventional therapy compared to no intervention, placebo or conventional therapy, were included. The outcomes included the evaluation of functional activities, pain and adverse effect. The risk of bias was evaluated using the Cochrane Collaboration tool. The estimated mean difference (MD) and SMD was within a 95% CI with respect to interstudy heterogeneity.

Results

12 studies with 982 participants were identified. The quality presented a high risk of bias. Meta-analysis found that DJD combined with glucosamine (MD 4.20 (1.72 to 6.69); p<0.001) or DJD plus meloxicam and glucosamine (MD 3.48 (1.59 to 5.37); p<0.001) had a more significant effect in improving Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (total WOMAC scores). Also, meta-analysis presented more remarkable pain improvement when DJD plus sodium hyaluronate injection (MD 0.89 (0.26 to 1.53); p=0.006) was used. These studies demonstrated that active treatment of DJD in combination should be practiced for at least 4 weeks. Information on the safety of DJD or comprehensive therapies was insufficient in few studies.

Conclusions

DJD combined with Western medicine or sodium hyaluronate injection appears to have benefits for KOA. However, the effectiveness and safety of DJD is uncertain because of the limited number of trials and low methodological quality. Therefore, practitioners should be cautious when applying DJD in daily practice. Future clinical trials should be well designed; more research is needed.

Keywords: COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE, knee osteoarthritis, Duohuo jisheng decoction

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first systematic review to provide an objective assessment of Duhuo Jisheng decoction (DJD) for the management of knee osteoarthritis (KOA) by integrating different outcome measures from 12 randomised controlled trials.

The included trials were on the basis of evidence with a high risk of bias, and low-quality studies.

The effectiveness and safety of DJD and combination therapy for KOA is uncertain because of the limited number of included trials and methodological limitations.

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a major cause of pain and motor dysfunction, with an estimated prevalence between 12% and 35% in the general population throughout the world.1 2 Patients with KOA usually have a lower quality of life or are less active compared to people without KOA.3 4 Common risk factors for people with KOA are age, obesity, trauma of the joints in the knee due to repetitive movements (in particular squatting and kneeling) and type 2 diabetes.5 6 In some Asian countries, the increasing epidemiological data indicate that the high prevalence of KOA constitutes an important health topic, with intense medical care expenditures—especially for people over the age of 50 years.7–12 In light of this situation, the question of how to effectively manage degenerative joint disease in the knee has remained an extremely important issue, until now.

The main objectives in the management of KOA have been to alleviate pain, educate patients about their disease, restore function, slow down the progression of the disease and maintain a health-related quality of life.13 Based on existing treatment guidelines, the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) set up a committee to complete a systematic review of current evidence that would eventually develop recommendations for the treatment of KOA.14 15 However, at the time there was also an ongoing debate on possible treatment options in daily practice.16 17 Glucosamine and viscosupplementation, for instance, had inconclusive evidence due to the lack of sufficient studies using placebos as comparators, lack of evaluation of the worst outcome, and lack of long-term pharmaceutical and safety evaluations.18 19 In contrast, non-pharmacological treatments such as exercise, self-management education and reducing stress provided symptom relief with very few side effects.20 Alternative treatments such as herbal preparations,21 acupuncture,22 moxibustion,23 massage24 and tai chi25 were also being investigated for their efficacy in randomised controlled trials. At present, many clinicians do not hesitate to recommend herbs or herbal products to their patients for the effective treatment of several chronic diseases.26 In fact, researchers have recently discovered that Chinese herbal medicine, a kind of complementary and alternative therapy, may alleviate the symptoms of KOA.21 27–29

Duhuo Jisheng decoction (DJD) is a Chinese herbal recipe consisting of 15 commonly used herbs: Doubleteeth Pubescent Angelica Root (Duhuo, Radix Angelicae Pubescentis), Chinese Taxillus Twig (Sangjisheng, Herba Taxilli), Largeleaf Gentian Root (Qinjiao, Radix Gentianae Macrophyllae), Divaricate Saposhnikovia Root (Fangfeng, Radix Saposhnikoviae), Manchurian Wild Ginger (Xinxi, Herba Asari), Szechwan Lovage Rhizome (Chuanxiong, Rhizoma Chuanxiong), Angelica Root (Danggui, Radix Angelicae Sinensis), Rehmannia (Dihuang, Radix Rehmanniae Glutinosae), White Peony Root (BaiShao, Radix Paeoniae Alba), Cinnamon Bark (Rougui, Cortex Cinnamomi), Sclerotium of Tuckahoe (Fuling, Poria), Eucommia Bark (Duzhong, Cortex Eucommiae), Achyranthes Root (Niuxi, Radix Achyranthis Bidentatae), Ginseng Root (Renshen, Panax Ginseng) and Licorice root (Gancao, Radix Glycyrrhizae). DJD is documented in Bei Ji Qian Jin Yao Fang, a famous medical book dating as far back as the Tang Dynasty.30 According to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) theory, DJD can be mainly used to treat arthralgia syndrome, with the effects of eliminating stagnation, removing blood stasis, nourishing the liver and kidney, and also invigorating the Qi and blood.31 With the development of modern biological techniques, research on the mechanism of DJD showed that the decoction could promote chondrocyte proliferation and inhibit sodium nitroprussiate-induced chondrocyte apoptosis, and regulate the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α).32–36 In addition, the compounds in DJD proved to have potential synergy and pharmacological uses in the treatment of osteoarthritis through computational approaches.37 In recent years, a number of published clinical studies of DJD have reported its effectiveness in many cases, and randomised controlled trials showed that DJD could contribute to KOA-related symptom control.38–40 On the contrary, the clinical safety of DJD has been described in some studies with only small sample sizes or limited durations.41 42

Until now, few studies have systematically examined the effectiveness and safety of DJD treatment for KOA according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).43 Because of this, our study aims to evaluate the beneficial and harmful effects of DJD for KOA, from randomised controlled trials.

Methods

Database and search strategies

Seven databases including PubMed (1959–2015), EMBASE (1980–2015), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, 1996–2015), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, 1979–2015), Chinese Scientific Journal Database (VIP, 1989–2015), Wanfang data (1998–2015) and Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM, 1978–2015) were investigated up to 12 October 2015. The reference list of retrieved papers was also studied.

The following search terms were used individually or in combination: ‘Duhuo Jisheng’, ‘DuhuoJisheng’, ‘arthritis’, ‘osteoarthritis’, ‘knee osteoarthritis’, ‘knee arthritis’, ‘osteoarthritis of knee joint’ and ‘knee joint osseous arthritis’. To increase the search range, no date and no language limits were imposed. Also, no restrictions on population characteristics were imposed.

The specific search strategy of PubMed was presented as follows:

#1 Search (((((arthritis [Title/Abstract]) OR osteoarthritis [Title/Abstract]) OR knee osteoarthritis [Title/Abstract]) OR knee arthritis [Title/Abstract]) OR osteoarthritis of knee joint [Title/Abstract]) OR knee joint osseous arthritis [Title/Abstract]

#2 Search (Duhuo Jisheng [Title/Abstract]) OR DuhuoJisheng [Title/Abstract]

#3 Search (#1 and #2).

Study selection

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials on the use of DJD for the treatment of KOA were included while quasi-randomised controlled trials were not. Multiple publications reporting the same groups of participants were excluded to reduce overlapping data.

Types of participants

The diagnosis of participants was in accordance with the recognised criteria for KOA, such as the guideline established by American College of Rheumatology in 1995.44 Participants were excluded if they had rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing arthritis, joint tuberculosis, purulent arthritis, allergic arthritis, Kashin-Beck disease or Podagra.

Types of interventions

In the randomised controlled trials, the treatment groups were oral DJD or pill, modified DJD—used alone or combined with conventional treatments regardless of dosage—and preparation formulation and duration. The rule of ‘Jun-Chen-Zuo-Shi’ (also known as ‘sovereign-minister-assistant-courier’) is the basic principle of Chinese herbal formula.45 ‘Jun’ and ‘Chen’ herbs are the core of herbal formulae. According to the theory of the TCM formula, the key herbs in the modified DJD should include Doubleteeth Pubescent Angelica Root (Duhuo, Radix Angelicae Pubescentis), Largeleaf Gentian Root (Qinjiao, Radix Gentianae Macrophyllae), Divaricate Saposhnikovia Root (Fangfeng, Radix Saposhnikoviae), Manchurian Wild Ginger (Xinxi, Herba Asari) and Cinnamon Bark (Rougui, Cortex Cinnamomi).46 47 The number of modified herbs is limited to no more than 5 (n≤5).

Types of controls

The control group included no treatment, no placebo and no conventional therapies.

Types of outcomes

Functional activities and pain are the main evaluation index. The primary outcome was measured by Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (total WOMAC scores), Lequesne functional index (total Lequesne scores), Lysholm knee score scale (total Lysholm scores) and specific pain scales including visual analogue scale (VAS scores) or analogous pain scales. The secondary outcome was adverse drug reaction (ADR) or adverse event (AE).

Two authors (YZ and XL) conducted the literature search and study selection. Discrepancies in whether or not to include or exclude a study were resolved by consensus with a third investigator (YL).

Data extraction

Data abstraction included the first author's name, year of publication, sample size, diagnosis criteria, age and sex of the participants, details of the intervention and control, treatment duration, follow-up and outcome measurement for each study. Two authors (SW and XW) conducted data extraction independently according to predefined criteria.

Methodological quality assessment

Two authors (WZ and RZ) assessed the methodological quality of each trial independently according to the standards advised by the Cochrane handbook. Disagreement, if any, was resolved by discussion and reached consensus through a third party (YL). The risk of bias was evaluated for each study by assessing the randomisation process, the treatment allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, the completeness of the data, and the reporting of results and other bias. Selective reporting bias is judged according to the published protocol. Registered clinical trials were conducted on the websites of the Chinese clinical trial registry (http://www.chictr.org) and international clinical trial registry of the US National Institutes of Health (http://clinicaltrials.gov). We compared the outcomes between the study protocol and the final published trial. The two cases were considered as other bias: (1) if the trials were stopped early; (2) if the baseline was lack of balance. When inadequate information was presented in the trial and we were unable to explicitly judge ‘yes’ or ‘no’, the item was judged as ‘unclear’. Across studies, the risk of bias was considered by using one of the three answers: ‘high’, ‘low’, ‘unclear’.

Data synthesis

Data analysis was carried out using RevMan software (V.5.2) provided by Cochrane Collaboration. Given the characteristics of extracted data in the review, continuous outcomes were expressed as mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs. Heterogeneity was assessed by means of I2 statistic. I2 ≥50% represented high heterogeneity. Standardised mean difference (SMD) was used when the studies included in meta-analysis assessed the outcome based on different scales (eg, VAS 0-10 and VAS 0-100). We used the random-effect model to analyse the data of Chinese medicine because we thought that it would be more precise due to its large amount of clinical heterogeneity. Publication bias would be analysed by funnel plot analysis if sufficient studies (n≥10) were found.

Results

Description of included trials

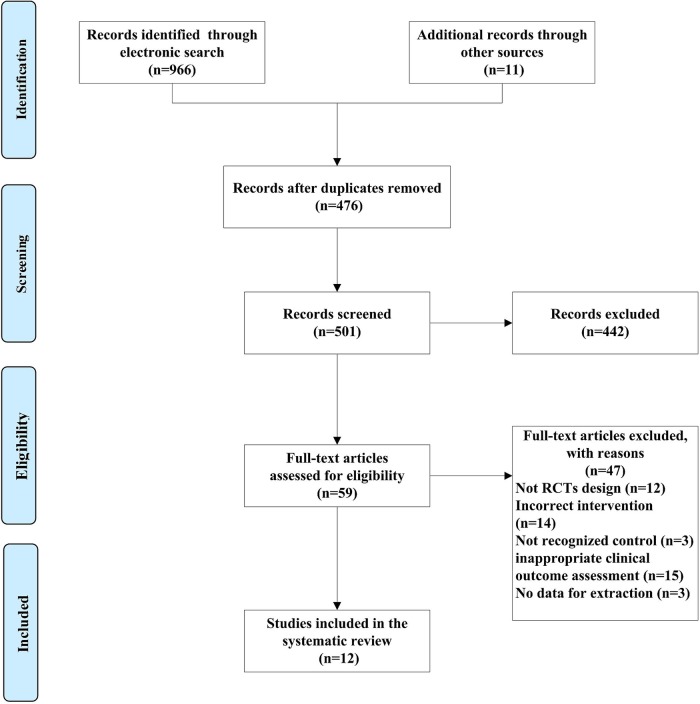

Among 966 identified studies and 11 additional studies, 12 studies were eligible for data extraction according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.30 39 48–57 The flow diagram for screening the trials is described in figure 1. One study was conducted in Thailand,30 the other studies in China.39 48–57 The language of enrolled trials included English30 and Chinese.39 48–57

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram (RCT, randomised controlled trial).

Study characteristics

Essential characteristics of the 12 studies are described in table 1. All the studies, including 490 patients from the treatment group and 492 controls, were recruited into this systematic review. Two different diagnostic criteria of KOA were used in the included trials: 11 trials used 1995 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for the medical management of osteoarthritis (ACR criteria–1995)30 39 48–51 53–57 and only one trial used 2007 Chinese Medical Association guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of osteoarthritis (CMA criteria–2007).52 The two sets of criteria for KOA were basically the same, depending mostly on the diagnosis of clinical manifestation and knee joint X-ray. The average age of patients enrolled in the review ranged from 51 to 71 years of age, and female participants accounted for 66.38% of the patients.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the included studies

| First author, year | Sample size (T/C) | Diagnosis criteria | Population characteristics | Treatment | Control | Duration of treatment | Follow-up | Outcome assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teekachunhatean, 200430 | 200 (100/100) | ACR criteria-1995 | T: mean age (62.66 years) M/F (22/78 cases) C: mean age (62.38 years) M/F (19/81 cases) |

DJW | Diclofenac 25 mg/time, PO, Tid | 4 weeks | None | Lequesne VAS AE |

| Yu, 201039 | 113 (56/57) | ACR criteria-1995 | T: mean age (56 years) M/F (21/35 cases) C: mean age (59 years) M/F (19/38 cases) |

DJD | Glucosamine 0.5 g/time, PO, Tid |

4 weeks | 4 weeks | Lequesne ADR |

| Cao, 201348 | 100 (50/50) | ACR criteria-1995 | T: mean age (61.5 years) M/F (24/26 cases) C: mean age (63.2 years) M/F (23/27 cases) |

DJD+control | Sodium hyaluronate 2 mL/time, intra-articular injection Once per week |

5 weeks | None | VAS ADR |

| Gu, 201349 | 60 (30/30) | ACR criteria-1995 | T: mean age (57.38 years) M/F (13/17 cases) C: mean age (54.98 years) M/F (12/18 cases) |

DJD | Meloxicam 7.5 mg/time, Qd |

4 weeks | None | Lysholm VAS |

| Yu, 201350 | 43 (21/22) | ACR criteria-1995 | T: mean age (55.2 years) M/F (8/13 cases) C: mean age (57.2 years) M/F (10/12 cases) |

DJD+control | Glucosamine 2 pills/time, PO, Tid |

4 weeks | 12 weeks | WOMAC |

| Zhang, 201351 | 80 (40/40) | ACR criteria-1995 | T: mean age (57 years) M/F (11/29 cases) C: mean age (56 years) M/F (12/28 cases) |

DJD+Control | Diacerein 50 mg/time, PO, Bid |

12 weeks | None | WOMAC VAS ADR |

| First author, year | Sample size (T/C) |

Diagnosis criteria | Population characteristics | Treatment | Comparison | Duration of treatment | Follow-up | Outcome assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhong, 201352 | 56 (28/28) | CMA criteria-2007 | T: mean age (70 years) M/F (10/18 cases) C: mean age (71 years) M/F (11/17 cases) |

DJD+control | Glucosamine 2 pills/time, PO, Tid |

6 weeks | None | WOMAC |

| Dong, 201453 | 60 (30/30) | ACR criteria-1995 | T: mean age (55.1 years) M/F (9/21 cases) C: mean age (51.26 years) M/F (8/22 cases) |

DJD+control | Knee arthroscopic surgery+rehabilitation training | 4 weeks | 6 months | Lysholm |

| Huang, 201454 | 70 (35/35) | ACR criteria-1995 | T: mean age (56.4 years) M/F (12/23 cases) C: mean age (53.26 years) M/F (15/20 cases) |

DJD+control | Sodium hyaluronate 20 mg/time, intra-articular injection Once per week |

T: 4 weeks C: 3 weeks |

12 weeks | Lysholm VAS |

| Jiang, 201455 | 40 (20/20) | ACR criteria-1995 | T: mean age (63.15 years) M/F (3/17 cases) C: mean age (62.3 years) M/F (3/17 cases) |

DJD+control | Meloxicam 7.5 mg/time, PO, Bid +Glucosamine 0.75 g/time, PO, Bid |

12 weeks | None | WOMAC ADR |

| Wang, 201456 | 100 (50/50) | ACR criteria-1995 | T: mean age (65.12 years) M/F (21/29 cases) C: mean age (64.3 years) M/F (24/26 cases) |

DJD+control | Glucosamine 2 pills/time, PO, Tid |

4 weeks | None | WOMAC |

| Zhou, 201457 | 60 (30/30) | ACR criteria-1995 | T: mean age (NA) M/F (NA) C: mean age (NA) M/F (NA) |

DJD+control | Meloxicam 15 mg/time, PO, Bid +Glucosamine 1.5 g/time, PO, Bid |

8 weeks | None | WOMAC ADR |

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ADR, adverse drug reaction; AE, adverse event; Bid, twice a day; C, control group; CMA, Chinese Medical Association; DJD, Duhuo Jisheng decoction; DJW, Duhuo Jisheng wan (Duhuo Jisheng pill); F, female; NA, not applicable; M, male; PO, oral administration; Qd, once a day; T, treatment group; Tid, three times a day; VAS, visual analogue scale.

All studies used DJD, except for one, which used Duhuo Jisheng wan (DJW; a Duhuo Jisheng pill).30 Among the included clinical trials, three trials compared DJW or DJD alone with conventional Western medicine including: diclofenac,30 glucosamine39 and meloxicam.49 Nine trials compared the combination of DJW or DJD and conventional treatments with conventional treatments such as sodium hyaluronate,48 54 knee arthroscopic surgery and rehabilitation training,53 glucosamine,50 52 56 diacerein,51 Meloxicam and glucosamine.55 57 The total duration of treatment ranged from 3 to 12 weeks. The follow-up was completed in four trials ranging from 1 to 6 months. Various outcomes were compared between the groups (table 1).

Risk of bias in included trials

The methodological quality of the included studies is described in table 2. The risk of bias was unclear for one study30 and high for 11 studies.39 48–57 Only one study used a random number table48 and the other trials did not provide detailed information regarding random sequence generation. Concealment of allocation, blinding of participants and researchers, and outcome assessment could be achievable in a randomised, double-blind and double-dummy controlled trial.30 However, the majority of trials did not report concrete details on allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors. In this review, blinding of participants and researchers was still difficult.39 48–57 Incomplete outcome data was low risk in six studies.30 39 49 50 53 54 Selective reporting could not be judged in all the studies because of the insufficient information provided. Other bias was evaluated to be of low risk in all the studies.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment in included studies based on the Cochrane handbook

| Included studies | Random sequence generation | Concealment of allocation | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other bias | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teekachunhatean et al30 | ? | + | + | + | + | ? | + | Unclear |

| Yu and Zhang39 | ? | ? | − | ? | + | ? | + | High |

| Cao et al48 | Random number table | ? | − | ? | ? | ? | + | High |

| Gu49 | ? | ? | − | ? | + | ? | + | High |

| Yu50 | ? | ? | − | ? | + | ? | + | High |

| Zhang and Sun51 | ? | ? | − | ? | ? | ? | + | High |

| Zhong and Zhong52 | ? | ? | − | ? | ? | ? | + | High |

| Dong53 | ? | ? | − | ? | + | ? | + | High |

| Huang and et al54 | ? | ? | − | ? | + | ? | + | High |

| Jiang55 | ? | ? | − | ? | ? | ? | + | High |

| Wang56 | ? | ? | − | ? | ? | ? | + | High |

| Zhou and Wang57 | ? | ? | − | ? | ? | ? | + | High |

+, Low risk of bias; −, high risk of bias; ?, unclear risk of bias.

Outcome measurements

In order to provide more accurate effectiveness of the treatments, we evaluated the effect according to various outcome scales and types of interventions. A change in total Lequesne scores, total Lysholm scores, total WOMAC scores and VAS scores was reported in the trials. Considering the different interventions, it could be divided into two groups—‘DJD versus conventional Western medicine’ and ‘DJD plus conventional therapies versus conventional therapies’. The summarised results of included trials are listed as follows.

Total Lequesne scores

Two studies compared DJD (DJW) with conventional Western medicine including diclofenac30 and glucosamine.39 The mean difference in Lequesne scores did not significantly differ between DJW group and diclofenac group after 4 weeks (p>0.05).30 However, the DJD group showed more significant improvement than glucosamine group after 4 weeks (p<0.01).39

Total Lysholm scores

One study compared DJD with comparators of meloxicam,49 while two studies assessed the effect of the combination of DJD with knee arthroscopic surgery and rehabilitation training53 or sodium hyaluronate injection.54 Considering the difference of therapeutic methods, no meta-analysis could be conducted.

DJD monotherapy showed a better effect compared with meloxicam in improving Lysholm scores after 2–4 weeks (p<0.05).49 DJD plus knee arthroscopic surgery and rehabilitation training provided more remarkable improvement, than surgery and training, at the beginning of 4 weeks (p<0.05).53 Similarly, the result showed that the therapeutic effect of DJD in combination with sodium hyaluronate injection was better than sodium hyaluronate injection alone after 12 weeks (p<0.05).54

Total WOMAC scores

All six studies compared DJD plus conventional Western medicine with the latter including glucosamine,50 52 56 diacerein,51 meloxicam and glucosamine.55 57 To reduce the clinical heterogeneity among the studies, three subgroups were analysed as follows:

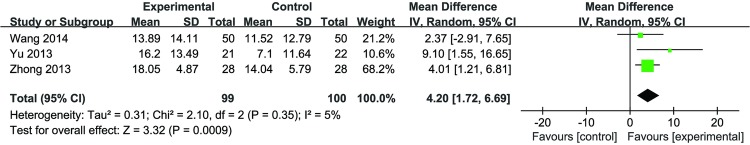

DJD plus glucosamine versus glucosamine: The pooled effects from three studies (n=99 vs 100) identified a significant effect of DJD compared with glucosamine (MD 4.20 (1.72 to 6.69); p=0.0009) with low heterogeneity (I2=5%) in figure 2.

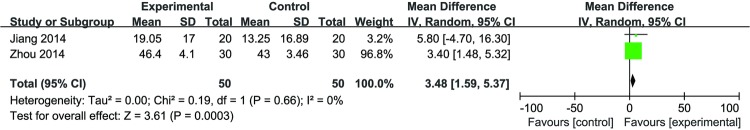

DJD plus meloxicam and glucosamine versus meloxicam and glucosamine: a meta-analysis (n=50 vs 50) of two trials demonstrated a significant improvement of DJD plus meloxicam and glucosamine, compared with meloxicam and glucosamine alone (MD 3.48 (1.59 to 5.37); p=0.0003) with low heterogeneity (I2=0%) in figure 3.

DJD plus diacerein versus diacerein: The result indicated DJD plus diacerein was better than diacerein alone in improving WOMAC scores after treatment at 12 weeks (p<0.01).51

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the effect of Duhuo Jisheng decoction plus glucosamine versus glucosamine in total WOMAC scores.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the effect of Duhuo Jisheng decoction plus meloxicam and glucosamine, versus meloxicam and glucosamine, in total WOMAC scores.

VAS scores

For VAS scores, two studies evaluated the effects of DJD (DJW) compared with conventional Western medicine including diclofenac30 and meloxicam.49 The mean difference in VAS scores did not significantly differ between DJW group and diclofenac group after 4 weeks (p>0.05).30 But the DJD group showed more remarkable improvement than meloxicam group after 4 weeks (p<0.05).49

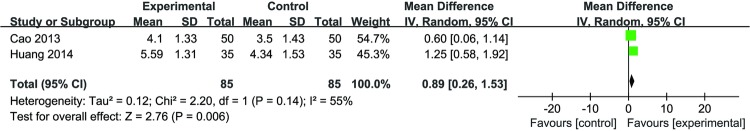

Three studies reported the combined effect of DJD and conventional therapy that covered sodium hyaluronate injection48 54and diacerein.51 Meta-analysis (n=85 vs 85) of two trials demonstrated a significant improvement between the DJD plus sodium hyaluronate injection and sodium hyaluronate injection alone (MD 0.89 (0.26 to 1.53); p=0.006) with high heterogeneity (I2=55%) (figure 4). The other study indicated DJD plus diacerein was better than diacerein alone in improving VAS scores after 12 weeks (p<0.01).51

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the effect of Duhuo Jisheng decoction plus sodium hyaluronate injection versus sodium hyaluronate injection in visual analogue scale (VAS) scores.

Adverse effects

Adverse effects were reported in six studies and not mentioned in others.30 39 48 51 55 57 Common AEs occurring in the DJW group were raised blood pressure (16%), central nervous system symptoms (including dizziness, somnolence and drowsiness) (16%) and gastrointestinal symptoms (including nausea/vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhoea and constipation) (12%).30 ADR was not found in the study by Yu and Zhang.39 However, none of the adverse effects were serious in the DJD groups.

The remaining four studies observed adverse effects of DJD plus conventional therapy when compared with conventional therapy. Both studies observed two cases of diarrhoea and nausea,48 51 while one of the trials also reported a case of dizziness.51 No significant abnormality was seen in the routine blood examination or in liver and renal function in the other two studies.55 57

Funnel plot analysis

According to the different intervention and outcome measurements, funnel plot analysis could not be completed because of the small number of included studies (<10) in the meta-analysis.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

As an adjunctive treatment method to KOA, Chinese herbal medicine has been used in clinical practice for many years.58–60 DJD is a popular TCM formula for the treatment of arthralgia and functional disorders in patients with KOA. This review compared the effectiveness and safety of DJD (DJW) against conventional treatment, as well as DJD plus conventional treatment against conventional treatment alone, for the management of KOA. It is the first systematic review to provide an objective assessment of DJD for the management of KOA by integrating different outcome measures from 12 randomised controlled trials. A detailed subgroup analysis based on different comparisons revealed the clinical outcome of KOA.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that DJD (duration ranging 4–12 weeks) combined with glucosamine or meloxicam and glucosamine had a more significant effect associated with total WOMAC scores. The meta-analysis of two trials presented more remarkable pain improvement when DJD (duration ranging 4–5 weeks) plus sodium hyaluronate injection was used. As there was a lack of study for the dose–response relationship, the dosage of the active treatment of DJD was difficult to precisely define. The high heterogeneity across studies was mainly owing to the use of different medications.

On the contrary, information on the safety of DJD or comprehensive therapies including DJD was insufficient in few studies. Based on the limited data, whether they were the adverse effect of DJD alone or of the combination of DJD with conventional therapy is not known, but the most common gastrointestinal symptoms (including nausea and diarrhoea) were found in three trials.30 48 51

Limitations

One limitation of this review was that the results are on the basis of evidence that has a high risk of bias and low quality. All 12 included studies declared randomisation, but only one study described a concrete random method.48 Only one placebo-controlled trial in the form of a pill implemented allocation concealment and double-blind study.30 The lack of a placebo control was of critical concern and is a common problem confronted by TCM research on the whole.61 There was no comparator of placebo in the previous studies, therefore, placebo effects were still not completely eliminated. Nevertheless, it is difficult to prepare a placebo that has the same colour, taste and flavour as a Chinese herbal decoction.62 Blinding of the outcome assessors was unclear in most of the investigated studies. Six studies do not explicitly describe study drop-outs and withdrawals.48 51 52 55–57 The protocol in the research was not public or visible so selective reporting was difficult to judge.

Further limitations were the decision to pool the results of the trials, putting DJD and DJW together, and the fact that the duration of treatment between the groups was not considered. First, the efficacy of the similar drug compositions but not identical dosage forms might be different in clinical practice.63 Second, the duration of treatments varied; this might have influenced the pooled effects of the review to some extent. Otherwise, long-term effects (more than 1 year) could not be found in the current study. Furthermore, attention was given only to the functional and pain scales assessed by the total scores or VAS scores, however, the sub-items in the scales, such as joint stiffness and swelling, were not considered. Quality of life was always applied to the evaluation of KOA64–66 but the design in the included trials was rarely seen.

Implications for practice

Based on our investigation, DJD combined with conventional Western medicine seems to be efficacious in improving total WOMAC scores in people with KOA. Also, DJD plus sodium hyaluronate injection may have a positive effect on reducing pain (VAS scores). It is recommended that DJD should be practiced for at least 4 weeks, however, the current findings are unsupported by the low-quality evidence, and we draw no comprehensive or final conclusions about the effectiveness and safety of the treatments. Moreover, the severity of patients with KOA was not reported in most studies. To discover whether different severities of KOA can be treated by this integrative medicine method, it is necessary to obtain more high-quality studies to use as evidence.

Implications for research

More trials with high methodological quality and adequate power are needed to further identify the effectiveness and safety of DJD or DJD plus conventional treatments. Rigorous methods of design, measurement and evaluation (DME) following the Cochrane Handbook should be applied. Clinical trial registries should be encouraged to provide details of the protocols for treating KOA—specifically, placebo-controlled clinical trials are essential, although not enough for Chinese herbal decoctions. Furthermore, careful consideration of the interventions for responding to different levels of KOA severity is required to find optimal subgroups that provide greater benefits than harm. Outcome measures should include the evaluation of sub-items in the internationally recognised scales. Quality of life and long-term effect should be assessed as well.

Conclusions

Overall, DJD combined with conventional Western medicine or other therapy appears to have benefits for improving physical function and decreasing pain for KOA. The safety of DJD and combination therapies is uncertain because of the limited number of included trials. The methodological limitations reduce the confidence in the effect estimates in the present systematic review. Future studies should overcome the limitations to more precisely assess the effectiveness and safety of DJD. Randomised controlled trials, for instance, should be strictly required in study design and reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michalein Dickinson from Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis for revising the English language of the paper. They thank Dong Y from China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences for improving the search strategies.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors made substantial contributions and approved the final version. WZ, YL and XW conceived the idea for the study; YZ and XL completed the literature search and study selection; SW and XW conducted data extraction; WZ and RZ evaluated the methodological quality; WZ, SW, RZ and XW conducted the meta-analysis and wrote the article.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81173282).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:476–99. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loyola-Sánchez A, Richardson J, MacIntyre NJ. Efficacy of ultrasound therapy for the management of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:1117–26. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yildiz N, Topuz O, Gungen GO et al. Health-related quality of life (Nottingham Health Profile) in knee osteoarthritis: correlation with clinical variables and self-reported disability. Rheumatol Int 2010;30:1595–600. 10.1007/s00296-009-1195-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkan BM, Fidan F, Tosun A et al. Quality of life and self-reported disability in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2014;24:166–71. 10.3109/14397595.2013.854046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidari B. Knee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: part I. Caspian J Intern Med 2011;2:205–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eymard F, Parsons C, Edwards MH et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis progression. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:851–9. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felson DT, Nevitt MC, Zhang Y et al. High prevalence of lateral knee osteoarthritis in Beijing Chinese compared with Framingham Caucasian subjects. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:1217–22. 10.1002/art.10293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang L, Rong J, Zhang Q et al. Prevalence and associated factors of knee osteoarthritis in a community-based population in Heilongjiang, Northeast China. Rheumatol Int 2012;32:1189–95. 10.1007/s00296-010-1773-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang H, Liu X, Shen L et al. Risk factors for and prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the rural areas of Shanxi Province, North China: a COPCORD study. Rheumatol Int 2013;33:2783–8. 10.1007/s00296-013-2809-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muraki S, Oka H, Akune T et al. Prevalence of radiographic knee osteoarthritis and its association with knee pain in the elderly of Japanese population-based cohorts: the ROAD study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2009;17:1137–43. 10.1016/j.joca.2009.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim I, Kim HA, Seo YI et al. The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in elderly community residents in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2010;25:293–8. 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.2.293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Song L, Liu G et al. Role of mtDNA haplogroups in the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in a southern Chinese population. Int J Mol Sci 2014;15:2646–59. 10.3390/ijms15022646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1145–55. 10.1136/ard.2003.011742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007;15:981–1000. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:132–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAlindon T, Zucker NV, Zucker MO. 2007 OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: towards consensus? Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:636–7. 10.1016/j.joca.2008.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henrotin Y, Chevalier X. [Guidelines for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis: for whom? Why? To do what?] Presse Med 2010;39:1180–8. 10.1016/j.lpm.2010.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henrotin Y, Mobasheri A, Marty M. Is there any scientific evidence for the use of glucosamine in the management of human osteoarthritis? Arthritis Res Ther 2012;14:201 10.1186/ar3657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Migliore A, Bizzi E, Herrero-Beaumont J et al. The discrepancy between recommendations and clinical practice for viscosupplementation in osteoarthritis: mind the gap! Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2015;19:1124–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burks K. Osteoarthritis in older adults: current treatments. J Gerontol Nurs 2005;31:11–19. 10.3928/0098-9134-20050501-05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsai CC, Chou YY, Chen YM et al. Effect of the herbal drug guilu erxian jiao on muscle strength, articular pain, and disability in elderly men with knee osteoarthritis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014;2014:297458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinman RS, McCrory P, Pirotta M et al. Acupuncture for chronic knee pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:1313–22. 10.1001/jama.2014.12660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim TH, Kim KH, Kang JW et al. Moxibustion treatment for knee osteoarthritis: a multi-centre, non-blinded, randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness and safety of the moxibustion treatment versus usual care in knee osteoarthritis patients. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e101973 10.1371/journal.pone.0101973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perlman AI, Ali A, Njike VY et al. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized dose-finding trial. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e30248 10.1371/journal.pone.0030248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang C, Iversen MD, McAlindon T et al. Assessing the comparative effectiveness of Tai Chi versus physical therapy for knee osteoarthritis: design and rationale for a randomized trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:333 10.1186/1472-6882-14-333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan SY, Zhou SF, Gao SH et al. New perspectives on how to discover drugs from herbal medicines: CAM's outstanding contribution to modern therapeutics. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:627375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao QW, Xu Y, Jin DE et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of Gubitong Recipe () in treating osteoarthritis of knee joint. Chin J Integr Med 2009;15:458–61. 10.1007/s11655-009-0458-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li XH, Liang WN, Liu XX. Clinical observation on curative effect of dissolving phlegm-stasis on 50 cases of knee osteoarthritis. J Tradit Chin Med 2010;30:108–12. 10.1016/S0254-6272(10)60024-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Cao Y, Pang J et al. Traditional Chinese herbal patch for short-term management of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012;2012:171706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teekachunhatean S, Kunanusorn P, Rojanasthien N et al. Chinese herbal recipe versus diclofenac in symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN70292892]. BMC Complement Altern Med 2004;4:19 10.1186/1472-6882-4-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma Y, Cui J, Huang M et al. Effects of Duhuojisheng Tang and combined therapies on prolapsed of lumbar intervertebral disc: a systematic review of randomized control trails. J Tradit Chin Med 2013;33:145–55. 10.1016/S0254-6272(13)60117-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu G, Chen W, Fan H et al. Duhuo Jisheng decoction promotes chondrocyte proliferation through accelerated G1/S transition in osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Med 2013;32:1001–10. 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen JS, Li XH, Li HT et al. Effect of water extracts from Duhuo Jisheng decoction on expression of chondrocyte G1 phase regulator mRNA. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2013;38:3949–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu G, Fan H, Huang Y et al. Duhuo Jisheng decoction-containing serum promotes proliferation of interleukin-1β-induced chondrocytes through the p16-cyclin D1/CDK4-Rb pathway. Mol Med Rep 2014;10:2525–34. 10.3892/mmr.2014.2527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu F, Liu G, Liang W et al. Duhuo Jisheng decoction treatment inhibits the sodium nitroprussiate-induced apoptosis of chondrocytes through the mitochondrial-dependent signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med 2014;34:1573–80. 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen CW, Sun J, Li YM et al. Action mechanisms of du-huo-ji-sheng-tang on cartilage degradation in a rabbit model of osteoarthritis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011;2011:571479 10.1093/ecam/neq002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng CS, Xu XJ, Ye HZ et al. Computational approaches for exploring the potential synergy and polypharmacology of Duhuo Jisheng decoction in the therapy of osteoarthritis. Mol Med Rep 2013;7:1812–18. 10.3892/mmr.2013.1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai JN, Chen HJ, Chen CC et al. Duhuo Jisheng Tang for treating osteoarthritis of the knee: a prospective clinical observation. Chin Med 2007;2:4 10.1186/1749-8546-2-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu JH, Zhang H. The clinical observation of Duhuo Jisheng decoction for knee osteoarthritis. Zhongguo Shi Yan Fang Ji Xue Za Zhi 2010;16:215–17. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu YG, Shen FX, Fang WL. 60 Cases clinical observation of Duhuo Jisheng decoction combined with sodium hyaluronate injection for knee osteoarthritis. Zhongguo Zhong Yi Gu Shang Ke Za Zhi 2014;22:49–50. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lai JN, Tang JL, Wang JD. Observational studies on evaluating the safety and adverse effects of traditional Chinese medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:697893 10.1155/2013/697893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsieh SC, Lai JN, Chen PC et al. Is Duhuo Jisheng Tang containing Xixin safe? A four-week safety study. Chin Med 2010;5:6 10.1186/1749-8546-5-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med 2009;3:e123–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hochberg MC, Altman RD, Brandt KD et al. Guidelines for the medical management of osteoarthritis. Part II. Osteoarthritis of the knee. American College of Rheumatology. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:1541–6. 10.1002/art.1780381104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu L, Wang Y, Li Z et al. Identifying roles of “Jun-Chen-Zuo-Shi” component herbs of QiShenYiQi formula in treating acute myocardial ischemia by network pharmacology. Chin Med 2014;9:24 10.1186/1749-8546-9-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li YB, Cui M, Yang Y et al. Similarity of traditional Chinese medicine formula. Zhong Hua Zhong Yi Yao Xue Kan 2012;30:1096–7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Feng B, Yang XC et al. Tianma gouteng yin as adjunctive treatment for essential hypertension: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:706125 10.1155/2013/706125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao GP, Hu JX, Wang CF. Clinical observation of Duhuo Jisheng decoction combined with sodium hyaluronate injection in intra-articular cavity injection in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Zhongguo Shi Yan Fang Ji Xue Za Zhi 2013;19:305–8. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gu CL. The Clinical Efficacy Study of Duhuo Jisheng decoction for knee osteoarthritis patients with the traditional Chinese medicine syndrome of Shen Xu Shi Zu. Nanjing: Nanjing Univ Chin Med 2013:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu HA. The clinical efficacy study of Duhuo Jisheng decoction combined with glucosamine for knee osteoarthritis patients with the traditional Chinese medicine syndrome of liver and kidney deficiency. Guang Dong Yi Xue Yuan Xue Bao 2013;31:560–2. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang L, Sun DY. Clinical observation of diacerein combined with Duhuo Jisheng decoction in the treatment of middle and aged people with knee osteoarthritis. Zhongguo Shi Yan Fang Ji Xue Za Zhi 2013;19:299–302. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhong LP, Zhong J. Clinical study of modified Duhuo Jisheng decoction combined with western medicine treatment for knee osteoarthritis. Nei Meng Gu Zhong Yi Yao 2013;88:450. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dong W. A comparative study on the clinical effect of Duhuo Jisheng decoction combined with arthroscopy in management of knee osteoarthritis. Jinan Shandong Univ Chin Med 2014:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang WY, Wei QS, Zeng JY et al. Effect of Duhuo Jisheng decoction with sodium hyaluronate on the quality of life of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Guang Dong Yi Xue 2014;35:2447–50. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiang YY. The clinical efficacy study of Duhuo Jisheng decoction for knee osteoarthritis patients with the traditional Chinese medicine syndrome of liver and kidney deficiency. Nanjing: Nanjing Univ Chin Med 2014:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang SG. Clinical observation of modified Duhuo Jisheng decoction for knee osteoarthritis. Bei Fang Yao Xue, 2014;11:78–9. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou LM, Wang YK. Observation on Du-Huo-Ji-Sheng decoction treatment for knee osteoarthritis. Cheng Du Zhong Yi Yao Da Xue Xue Bao 2014;37:46–8, 78. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cameron M, Chrubasik S. Oral herbal therapies for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;5:CD002947 10.1002/14651858.CD002947.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lechner M, Steirer I, Brinkhaus B et al. Efficacy of individualized Chinese herbal medication in osteoarthrosis of hip and knee: a double-blind, randomized-controlled clinical study. J Altern Complement Med 2011;17:539–47. 10.1089/acm.2010.0602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao G, Wu H, Tian J et al. Clinical efficacy of bushen huoxue qubi decoction on treatment of knee-osteoarthritis and its effect on hemarheology, anti-inflammation and antioxidation. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2012;37:390–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiong X, Li X, Zhang Y et al. Chinese herbal medicine for resistant hypertension: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2015;5:e005355 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sarris J. Chinese herbal medicine for sleep disorders: poor methodology restricts any clear conclusion. Sleep Med Rev 2012;16:493–5. 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang JN, Zhang GD, Yu RH et al. Thinking of the profound meaning of the dosage form by the traditional Chinese medicine clinical effects difference. Zhongguo Shi Yan Fang Ji Xue Za Zhi 2010;16:185–7. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh AK, Kalaivani M, Krishnan A et al. Prevalence of osteoarthritis of knee among elderly persons in urban slums using American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria. J Clin and Diagn Res 2014;8:JC09–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim HJ, Lee JY, Kim TJ et al. Association between serum vitamin D status and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in an older Korean population with radiographic knee osteoarthritis: data from the Korean national health and nutrition examination survey (2010–2011). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:48 10.1186/s12955-015-0245-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Visser AW, de Mutsert R, Bloem JL et al. Do knee osteoarthritis and fat-free mass interact in their impact on health-related quality of life in men? Results from a population-based cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:981–8. 10.1002/acr.22550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]