Abstract

Introduction

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is the treatment of choice for unexplained infertility. Preovulatory uterine flushing could reduce intrauterine debris and inflammatory factors preventing pregnancy and constitute an alternative to IVF. Our objective is to assess the efficacy of preovulatory uterine flushing with physiological saline for the treatment of unexplained infertility.

Methods and analysis

We will perform a randomised controlled trial based on consecutive women aged between 18 and 37 years consulting for unexplained infertility for at least 1 year. On the day of their luteinising hormone surge, 192 participants will be randomised in two equal groups to either receive 20 mL of physiological saline by an intrauterine catheter or 10 mL of saline intravaginally. We will assess relative risk of live birth (primary outcome), as well as pregnancy (secondary outcome) over one cycle of treatment. We will report the side effects, complications and acceptability of the intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

This project was approved by the Ethics committee of the Centre Hospitatlier Universitaire de Quebec (no 2015–1146). Uterine flushing is usually well tolerated by women and would constitute a simple, affordable and minimally invasive treatment for unexplained infertility. We plan to communicate the results of the review by presenting research abstracts at conferences and by publishing the results in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

NCT02539290; Pre-results.

Keywords: Unexplained infertility, Uterine flushing, Tubal flushing

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study could lead to a new, simple, minimally invasive and easily available treatment for unexplained infertility.

This randomised controlled trial protocol adopts rigorous methodology and is written in accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT).

This trial is powered to compare live births.

Blinding of participants may not be effective, given the additional discomfort that may be felt by women receiving uterine flushing compared to vaginal flushing. For this reason, we will assess the success of blinding by asking participants which intervention they think was administered.

Introduction

Infertility affects approximately one in six couples.1 In over a quarter of cases, the infertility remains unexplained.2 Unfortunately, effective treatment options are then limited.3 Ovarian stimulation with clomiphene citrate4 and intrauterine insemination5 have not been shown to be effective treatments. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)3 and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM)6 no longer recommend their use in unexplained infertility. Gonadotropins are associated with such high rates of multiple pregnancy that their use is only recommended as part of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) protocols, leaving IVF as the only current reasonable treatment.3 6

In the months following tubal patency tests, studies have reported an increase in pregnancies and live births.7 A growing body of evidence suggests that uterine flushing could promote fertilisation by removing debris from otherwise undamaged tubes and altering interleukin and prostaglandin production by macrophages.7–10 The endometrial abrasion caused by the insertion of a catheter could also contribute to the therapeutic effect.11 In a randomised controlled trial, Edelstam et al12 found a fivefold increase in pregnancy rates following a preovulatory hysterosalpingosonography with diluted lidocaïne (15% vs 3%, p=0.04). The 130 studied couples were suffering from unexplained infertility and otherwise treated with clomiphene citrate and intrauterine insemination. Those findings were not supported by a subsequent study by Lindborg et al,13 in which there was no difference in pregnancy rates between infertile couples receiving a hysterosalpingosonography using a galactose solution and the control group receiving no intervention (risk difference of 2.7%, CI −6.9 to 12.3%, p=0.63). However, in the latter study, no specific timing in the cycle was evaluated. Moreover, 11% of participants were not compliant with the protocol, of which 11 women allocated to no intervention received a hysterosalpingosonography in another clinic during the study period. This could have been avoided with an adequate blinding of participants by providing, for example, a vaginal flushing in the control group.

Uterine flushing is usually well tolerated14 and could represent a less expensive and better tolerated option than IVF. Physiological saline is the most affordable and the least invasive contrast avoiding any risk of allergy.15 In order to obtain an appropriate visualisation of the tubes, an average of 9 mL and up to 22 mL of contrast are injected into the uterus.16 The amount of fluid may have an important role to play in the ability to dislodge plugs or other debris from within the fallopian tubes.

We designed this randomised controlled evaluator and patient-blinded superiority trial with two parallel groups to assess the efficacy of uterine flushing with 20 mL of saline compared to vaginal flushing with 10 mL of saline on the day of the luteinising hormone (LH) surge for the treatment of unexplained infertility. Our objective is to assess its effect on the proportion of live births (primary outcome) and pregnancies (secondary outcome) over a cycle of treatment. We will also report side effects, complications and acceptability of the intervention.

Methods and analysis

The study will be conducted at the fertility clinic of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Quebec from 1 August 2015. This protocol is written in accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) and has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02539290). Any changes from the original protocol will be reported in the final article.

Women aged between 18 and 37 years with unexplained infertility for at least 1 year will be consecutively invited to participate in the study at a follow-up visit. Selection criteria are shown in box 1. We define unexplained infertility as a normal semen analysis, a proof of ovulation, a normal ovarian reserve, patent tubes and a normal uterine cavity.17 Tubal patency must be established by a hysterosalpingography, hysterosalpingosonography or laparoscopy prior to enrolment.18 Women with an abnormal uterine cavity will be excluded except for those with an arcuate uterus given the lack of impact of the latter on reproductive outcomes.19

Box 1. Selection criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Primary or secondary infertility ≥12 months

Women aged ≥18 and ≤37 years

- Diagnosis of unexplained infertility ≤36 months

- Anti-Müllerian hormone ≥0.4 ng/mL and/or follicle-stimulating hormone ≤13 IU/L in early follicular phase

- Regular cycle of 25–35 days, positive ovulation tests, and/or luteal phase serum progesterone ≥25 mmol/L in a natural cycle

- Normal semen analysis*

- Normal uterine cavity

- Patent tubes

Negative genitourinary test for gonorrhoea and chlamydia ≤12 months

Exclusion criteria

Body mass index ≥35 kg/m2

Ongoing pregnancy

*According to the WHO criteria 2010.

Electronic records of all women presenting at the fertility clinic will be assessed for eligibility by a research assistant. Eligible women will be identified and invited to participate by their clinician at the time of their consultation. Further information will then be provided by a research assistant at the end of the consultation or by phone in the following days.

A simple computer-generated randomisation will be carried out by an independent statistician in a ratio of 1:1 and transferred into sealed opaque envelopes. Participating women will monitor their cycle by detecting the LH surge using test sticks in a urine sample. On the morning of their positive result, women will come to the clinic. A consultant gynaecologist or a trained resident in gynaecology will then obtain their written consent, allocate the intervention and administer the intervention.

After removing excess vaginal and cervical secretions with a cotton swab, a 5 Fr shapeable intrauterine insemination catheter (Thomas Medical, Indianapolis, USA) will be introduced into the cervical canal, preferably without the use of a tenaculum. Then, 20 mL of physiological saline will be injected through the catheter. In case of leakage, an additional 20 mL may be administered at the clinician's discretion. In the control group, 10 mL of physiological saline will be injected intravaginally to ensure that participants are blinded to the intervention. This will avoid the use of co-interventions and control for any placebo effect.20 No catheter will be introduced into the uterus given that endometrial scratching could be therapeutic in itself.11 We will use physiological saline at room temperature.

In both groups, sexual intercourse will be recommended within 12 h of the intervention. Couples must agree to take no other fertility treatment in the studied cycle. No premedication will be given. In case of pelvic pain, women will be advised to take acetaminophen if needed and avoid anti-inflammatory drugs. Participants, care providers, outcome assessors and data analysts will be blinded to treatment assignment.

The primary outcome is the difference in the proportion of live births, resulting from one cycle of treatment, between the two intervention groups. This outcome will be assessed 10 months after randomisation using a phone interview and will be confirmed by a medical record. Live births must result from the cycle targeted by the intervention, which will be verified using the first or second trimester ultrasound. The secondary outcome is the difference in the proportion of pregnancies (positive urinary or serum pregnancy test, gestational sac on ultrasound or histological evidence of trophoblastic tissue) resulting from one cycle of treatment between the two groups. This outcome will be assessed 1 month after randomisation using a phone interview and, when possible, medical data. Live births were chosen as primary outcome rather than pregnancies, the latter being a surrogate outcome in infertility. Adverse effects will be reported. After completing the intervention, the clinician will document the following symptoms: pain (none, mild, moderate, severe), nausea, vomiting, weakness, dizziness or loss of consciousness. At 1 month, participants will be asked if they have experienced fever, pelvic infection or any other late adverse effects in a phone interview. They will also be asked if they think uterine flushing is an acceptable treatment option and if they would be willing to repeat this treatment for a new cycle. Finally, phone interviews at 1 and 10 months will be used to document the occurrence of spontaneous abortions, ectopic pregnancies and multiple pregnancies.

Baseline information will be collected using a paper-based questionnaire completed by participants at home and presented to the gynaecologist on the day of the intervention. The questionnaire gathers information about potential confounders including: age of the male and female partner, ovarian reserve, sperm concentration, duration of infertility, previous fertility treatments, frequency of sexual intercourse, parity, body mass index, physical activity, use of tobacco, coffee, alcohol and drugs, ethnicity, salary, stress level, education level, marital status, number of sexual partners, as well as history of sexually transmitted infection, pelvic inflammatory disease and pelvic surgery.1 2 21–27 Details on the conduct of the intervention (injection pressure (low, moderation or high), leakage (yes or no), ease of procedure (easy, difficult or impossible), use of a tenaculum (yes or no), quantity of saline injected (in mL)) will be reported by the gynaecologist or the resident performing the intervention.

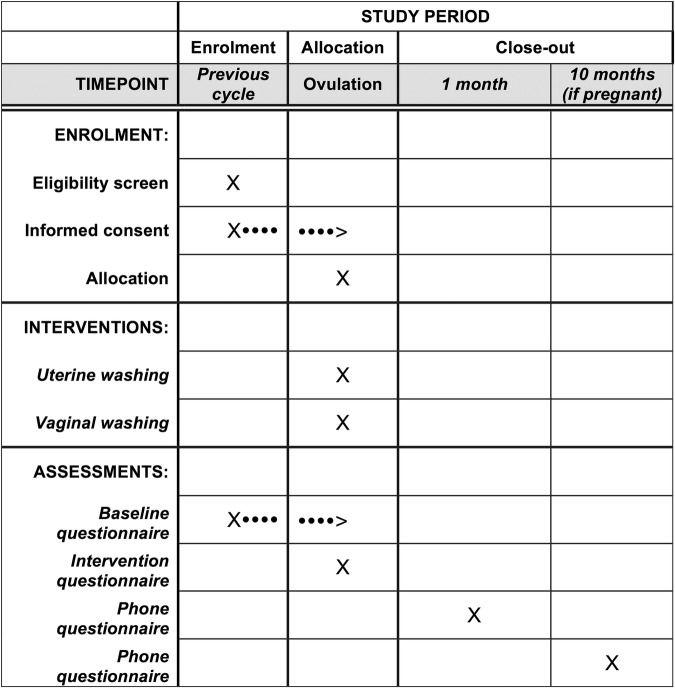

All participants will be contacted by phone 1 month following the intervention to document pregnancy, late adverse effects, compliance with the protocol (sexual intercourse within 12 h after the intervention and non-use of other fertility treatment) and treatment acceptability. At that time, we will assess the success of blinding by asking participants which intervention they think was administered. Pregnant participants will be reached over the phone 9 months later to assess pregnancy outcome. A blinded research assistant will administer phoned based interviews with a structured questionnaire. If not reachable after three attempts, participants will be contacted by email with their consent previously obtained. The primary outcome (live birth) and any event requiring a medical consultation will be verified using the medical record (eg, pelvic infection, spontaneous abortion and ectopic pregnancy). All questionnaires were piloted on five women. The participant timeline is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participant timeline.

Statistical analysis

Results will be presented using frequencies and means. We will calculate relative risks with exact 95% CIs. If participant characteristics are poorly balanced between the two groups, we will also present adjusted and unadjusted relative risks using a modified Poisson model. Results of intention to treat and per-protocol analyses will be presented.

Exploratory subgroup analyses will be conducted for the following potential modifiers: age <30 years vs ≥30 years old; duration of infertility <2 years vs ≥2 years; suspected versus non-suspected endometriosis; high versus low injection pressure; use versus non-use of a tenaculum; occurrence versus non-occurrence of leakage; intervention done by a gynaecologist versus a resident; and ≤20 mL vs >20 mL of saline. Observations with missing data on the outcome variables will be censored at the date of the last contact. If multivariable regression analyses are performed, missing data on adjustment variables, if they appear random, will be addressed using multiple imputation.

Sample size estimation was based on live birth rates observed in the study of Edelstam et al12 (14% in the flushing group and 3% in the non-flushing group) and an estimated dropout rate of 3% (0% in two previous studies13). With α=0.05, β=0.20, and bilateral testing, we will need to recruit 192 women.

Ethics and dissemination

Participating women will be asked to sign the informed consent form. At any time, women will be able to withdraw from the study. Data will be entered electronically. Original study forms will be kept locked at the study site and maintained in storage for a period of 3 years after the completion of the study. All data sets will be password protected and only available to project investigators. Data sets cleaned and blinded of any identifying participant information, as well as the full protocol, will be available after the completion of the trial on request to the contacting author.

Uterine flushing is generally well tolerated. In a previous study, adverse effects occurred in 8.8% of women and included moderate-to-severe pain (4%), vagal symptoms (3%), nausea (1%) and vomiting (0.5%).14 Pelvic infections are infrequent and were reported to occur in 0.17% of cases.14 To reduce the risk of infection, all participants will have to present a negative genitourinary test for gonorrhoea and chlamydia in the past 12 months. In addition, we will rule out the possibility of an ongoing pregnancy by performing a urinary pregnancy test before the intervention.

A data and safety monitoring committee will review adverse events after 92 women are enrolled. The committee consists of two independent researchers with experience in gynaecology. They will be unaware of treatment assignment unless they raise concerns and unblinding is judged necessary.

We anticipate that the study will be completed by 31 July 2017. We plan to communicate the results by presenting research abstracts at conferences and by publishing the results in a peer-reviewed journal. This study could bring a new alternative for the treatment of unexplained infertility. Compared to IVF, uterine flushing causes no increased risk of hyperstimulation syndrome and multiple pregnancy and would represent a less expensive and better tolerated option. It could constitute a simple, minimally invasive and easily available treatment, even in limited resource facilities.

Registration

The original protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov on 26 August 2015: Registration number NCT02539290. This article presents the second version of the protocol issued on 27 November 2015 (statements were added to better clarify the methodology in response to comments of the reviewers and editorial board).

Footnotes

Contributors: SM-L under the supervision of SD and M-ÈB, developed the objectives of the study and established their relevance in relation to the current literature. SM-L developed the methodology and drafted the first version of the manuscript with significant input from all other authors. SM-L, SD, LM and EB ensured the methodological quality of the study and M-ÈB, SD and JL led integration into the clinical setting. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Fonds d'approche intégrée en santé des femmes.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Centre Hospitatlier Universitaire de Quebec (no 2015–1146).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bushnik T, Cook JL, Yuzpe AA et al. Estimating the prevalence of infertility in Canada. Hum Reprod 2012;27:738–46. 10.1093/humrep/der465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hull MG, Glazener CM, Kelly NJ et al. Population study of causes, treatment, and outcome of infertility. BMJ 1985;291:1693–7. 10.1136/bmj.291.6510.1693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Fertility: assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems. London: NICE; 2013. CG156. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG156 (accessed 10 Apr 2015)..

- 4.Hughes E, Brown J, Collins JJ et al. Clomiphene citrate for unexplained subfertility in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(1):CD000057 10.1002/14651858.CD000057.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veltman-Verhulst SM, Cohlen BJ, Hughes E et al. Intra-uterine insemination for unexplained subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9:CD001838 10.1002/14651858.CD001838.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Use of clomiphene citrate in infertile women: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2013;100:341–8. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohiyiddeen L, Hardiman A, Fitzgerald C et al. Tubal flushing for subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;5:CD003718 10.1002/14651858.CD003718.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson J, Montoya I, Olive D. Ethiodol oil contrast medium inhibits macrophage phagocytosis and adherence by altering membrane electronegativity and microviscosity. Fertil Steril 1992;58:511–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikulska D, Kurzawa R, Ròzewicka L. Morphology of in vitro sperm phagocytosis by rat peritoneal macrophages under influence of oily contrast medium (Lipiodol). Acta Eur Fertil 1994;25:203–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukui A, Fujii S, Yamaguchi E et al. NK cell subpopulations and cytotoxicity for infertile patients undergoing in vitro fertilisation. Am J Reprod Immunol 1999;41:413–22. 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1999.tb00456.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibreel A, Badawy A, El-Refai W et al. Endometrial scratching to improve pregnancy rate in couples with unexplained subfertility: a randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2013;39:680–4. 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.02016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edelstam G, Sjösten A, Bjuresten K et al. A new rapid and effective method for treatment of unexplained infertility. Hum Reprod 2008;23:852–6. 10.1093/humrep/den003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindborg L, Thorburn J, Bergh C et al. Influence of HyCoSy on spontaneous pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod 2009;24:1075–9. 10.1093/humrep/den485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dessole S, Farina M, Rubattu G et al. Side effects and complications of sonohysterosalpingography. Fertil Steril 2003;80:620–4. 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00791-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saunders RD, Shwayder JM, Nakajima ST. Current methods of tubal patency assessment. Fertil Steril 2011;95:2171–9. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayida G, Kennedy S, Barlow D et al. A comparison of patient tolerance of hysterosalpingo-contrast sonography (HyCoSy) with Echovist-200 and X-ray hysterosalpingography for outpatient investigation of infertile women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1996;7:201–4. 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1996.07030201.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelbaya TA, Potdar N, Jeve YB et al. Definition and epidemiology of unexplained infertility. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2014;69:109–15. 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maheux-Lacroix S, Boutin A, Moore L et al. Hysterosalpingosonography for diagnosing tubal occlusion in subfertile women: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 2014;29:953–63. 10.1093/humrep/deu024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin P, Bhatnagar K, Nettleton G et al. Female genital anomalies affecting reproduction. Fertil Steril 2002;78:899–915. 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03368-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnhart KT. Placebo effect in fertility: advantageous or false advertisement? Fertil Steril 2014;101:36–7. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins JA, Rowe TC. Age of the female partner is a prognostic factor in prolonged unexplained infertility: a multicenter study. Fertil Steril 1989;52:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maher J, Macfarlane A. Trends in live births and birthweight by social class, marital status and mother's age, 1976–2000. Health Stat Q 2004(23):34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tietze C. Reproductive span and rate of reproduction among Hutterite women. Fertil Steril 1957;8:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de La Rochebrochard E, de Mouzon J, Thépot F et al. Fathers over 40 and increased failure to conceive: the lessons of in vitro fertilization in France. Fertil Steril 2006;85:1420–4. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins JA, Burrows EA, Wilan AR. The prognosis for live birth among untreated infertile couples. Fertil Steril 1995;64:22–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahamondes L, Bueno JG, Hardy E et al. Identification of main risk factors for tubal infertility. Fertil Steril 1994;61:478–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson NP, Farquhar CM, Hadden WE et al. The FLUSH trial—flushing with lipiodol for unexplained (and endometriosis-related) subfertility by hysterosalpingography: a randomized trial. Hum Reprod 2004;19:2043–51. 10.1093/humrep/deh418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]