Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to investigate the factors related to prolonged on-scene times, which were defined as being over 30 min, during ambulance transportation for critical emergency patients in the context of a large Japanese city.

Design

A population-based observational study.

Setting

Kawasaki City, Japan's eighth largest city.

Participants

The participants in this study were all critical patients (age ≥15 years) who were transported by ambulance between April 2010 and March 2013 (N=11 585).

Outcome measures

On-scene time during ambulance transportation for critical emergency patients.

Results

The median on-scene time for all patients was 17 min (IQR 13–23). There was a strong correlation between on-scene time and the number of phone calls to hospitals from emergency medical service (EMS) personnel (p<0.001). In multivariable logistic regression, the number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel, intoxication, minor disease and geographical area were associated with on-scene times over 30 min. Age, gender, day of the week and time of the day were not associated with on-scene times over 30 min.

Conclusions

To make on-scene time shorter, it is vital to redesign our emergency system and important to develop a system that accommodates critical patients with intoxication and minor disease, and furthermore to reduce the number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel.

Keywords: ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study population consisted of 11 585 critical patients (age ≥15 years) who were transported by ambulance for 3 years in Japan's eighth largest city.

This study is the first to focus on factors related to prolonged on-scene time during ambulance transportation for critical emergency patients in a big city.

Our findings may not be generalisable to rural districts because our study was conducted in a big city.

Introduction

Total prehospital time consists of response time (the time from ambulance call receipt to arrival of the ambulance at the scene), on-scene time (the time from arrival of the ambulance at the scene to departure), and transport time (the time from departure of the ambulance at the scene to arrival at the hospital). Recently, the Japanese government reported that the average total prehospital time has gradually increased by about 10 min over a decade—from 28.8 min in 2002 up to 38.7 min in 2012.1

The prolongation of total prehospital time is a social problem in Japan. It negatively affects the outcomes for critical patients and inhibits the effective utilisation of ambulances.2–4 Kosaka and Yoshioka2 reported that hospital mortality for patients with acute cardiac failure was associated with the duration between on-scene time and transport time. Kelly et al3 also showed that patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction who did not receive thrombolytic therapy within 90 min of calling for medical assistance had an increased risk of death. Therefore, it is very important to reduce the total prehospital time as much as possible. Of the total prehospital time, on-scene time is particularly prolonged because of the expansion of the range of emergency treatments performed by the emergency life-saving technician (ELST) and also by the time taken for hospital selection.5 Even in big cities where there are a lot of hospitals, the same problems occur.

There have been few studies for prolonged on-scene time during ambulance transportation for critical emergency patients in a big city. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the factors related specifically to the prolongation of on-scene time during ambulance transportation for critical emergency patients within the context of a large Japanese city.

Methods

Study design, setting and selection of participants

The study was a population-based observational study conducted in Kawasaki City, the eighth largest city in Japan, with a population of 1.43 million (as of 2013) and a land area of 142.7 km2.6 We retrospectively screened every patient who was transported by ambulance in Kawasaki City from 1 April 2010 to 31 March 2013 (N=164 122). Only the patients who the physicians in charge at emergency departments (EDs) classified as critical were included in this study. Critical patients were defined according to the national criteria as those who are expected to be hospitalised for more than 3 weeks or are confirmed dead by the physicians in charge at EDs.1 We excluded patients who were aged under 15 years and cases of hospital transfer.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Teikyo University. The Ethics Committee waived the need for informed consent due to the anonymity of the data collected for routine operations and the retrospective nature of this study.

The Japanese and Kawasaki city's emergency medical service system

The Japanese emergency medical service (EMS) system is operated by a municipality, and its response consists of a single tiered ambulance system that is dispatched for all patients who need ambulance transportation. Each ambulance has at least three EMS personnel, and there is at least one ELST in almost every ambulance. ELSTs are licensed to insert an intravenous line and to place advanced airway management devices for only patients with cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) under online medical control direction. In addition, specially trained ELSTs are permitted to insert tracheal tubes and to administer intravenous epinephrine for only patients with CPA. Since April 2014, specially trained ELSTs have been permitted to insert an intravenous line and administer intravenous lactated Ringer's solution and to measure the blood glucose and administer intravenous glucose if the patient’s blood glucose is low for life-threatening patients. Ambulance service is free of charge.

The Kawasaki Fire Department is responsible for ambulance service in Kawasaki City and had 26 ambulances in 2012. Each ambulance has three EMS personnel, and 99.7% of ambulances had at least one ELST in 2012. Emergency transportations are provided for patients whose symptoms can worsen immediately or who are critically ill, and all patients except those who refuse to travel to hospitals or are already dead are transported to hospitals. Kawasaki city has the checking system for emergency transportation by medical control council. There were three tertiary care emergency centres and 24 acute care hospitals in Kawasaki City in 2012. EMS personnel record initial medical data for all patients whom they transport to hospital on recording papers, and the physicians in charge at EDs check their severities. Finally, the Kawasaki Fire Department keeps them.

Data collection

The data were obtained with the permission of the Kawasaki Fire Department. The data included the following information: age and gender of the patient, the day of the week, the time of the ambulance call, the fire station from which the ambulance was dispatched, the number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel, the disease name as diagnosed at the EDs, response time, on-scene time, and transport time.

Statistical analysis

Prolonged on-scene time was defined as over 30 min because over 30 min is usually used as the prolonged on-scene time in Japanese government reports. To analyse characteristics of patient demographics and backgrounds in relation to on-scene time, normally or near normally distributed continuous variables were presented as means and SD and were compared using the Student t test. Non-normally distributed continuous data were presented as medians and IQRs and were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test. Age was divided into three groups: 15–64 years, 65–84 years and over 85 years. Day of the week was divided into 2 groups: weekday and weekend. Time of ambulance call was divided into three groups: night shift (midnight to 08:00), day shift (08:00–16:00), and evening shift (16:00 to midnight). The fire stations from which the ambulances were dispatched were divided into three geographical areas: north, middle and south. The diseases, as diagnosed at the EDs, were divided into 12 groups: CPA, trauma, burn injury, intoxication, other external causes, central neurological diseases, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, renal and urogenital diseases, other internal causes and minor diseases. Other external causes included: heat stroke, hypothermia, hanging, asphyxia, drowning and foreign body. Other internal causes included: disturbance of consciousness and shock of unknown origin, haematological diseases, immunological diseases, endocrine metabolic diseases and neuromuscular diseases. Minor diseases included: eye diseases, skin diseases, nose and throat diseases, obstetrical and gynaecological diseases, psychiatric disorders, breast diseases and orthopaedic diseases except for trauma. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to investigate the factors related to on-scene time over 30 min. Age, gender and disease as diagnosed at the ED were included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis, and the following variables were applied to multivariable logistic regression analysis using a stepwise selection, if the univariate p value was <0.2: the day of the week, the time of the ambulance call (time of the day), the fire station from which the ambulance was dispatched (geographical area), and the number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel. Data were presented as ORs with 95% CIs. All p-values were two sided, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, North Carolina, USA).

Results

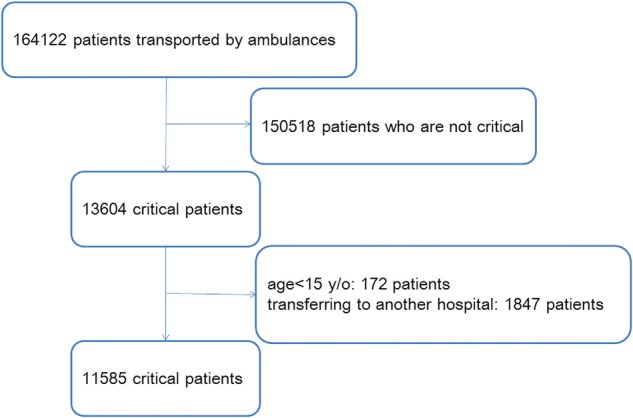

Of 164 122 patients transported by ambulances during the study period, the critical patients numbered 13 604. Among them, 11 585 patients were included in our analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study profile with selection of participants.

Table 1 shows the distribution of response time, on-scene time and transport time. Median on-scene time was 17 min (Q1=25 centile, Q3=75 centile, IQR 13–23).

Table 1.

The distribution of response time, on-scene time and transport time

| 25 centile | Median | 75 centile | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response time (min) | 6 | 7 | 9 |

| On-scene time (min) | 13 | 17 | 23 |

| Transport time (min) | 5 | 7 | 11 |

The demographics and backgrounds of study patients are shown in table 2. On-scene time of age, gender, time of day, geographical area and disease, as diagnosed at the ED, were statistically significant among groups in each category. With regard to the diseases, on-scene times for CPA, trauma, burn injury, intoxication, central neurological diseases, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, other internal causes and minor diseases were statistically significant compared with the other diseases. On-scene times for CPA and cardiovascular diseases were relatively shorter than for the other diseases. On-scene times for trauma, burn injury, intoxication, central neurological diseases, respiratory diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, other internal causes and minor diseases were relatively longer than for the other diseases. Day of the week was not statistically significantly different in each category.

Table 2.

Patient's demographics and backgrounds

| Number | On-scene time (min) Median (IQR) |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 11 585 | 17 (13–23) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 15–65 | 3446 | 17 (13–24) | <0.001 |

| 65–85 | 5261 | 17 (13–23) | |

| 85+ | 2878 | 17 (13–24) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 6627 | 17 (13–23) | <0.001 |

| Female | 4958 | 18 (13–24) | |

| Day of week | |||

| Weekday | 8249 | 17 (13–23) | 0.86 |

| Weekend | 3336 | 17 (13–23) | |

| Time of the day | |||

| Night shift | 2676 | 18 (13–24) | <0.001 |

| Day shift | 4792 | 17 (13–22) | |

| Evening shift | 4117 | 17 (13–23) | |

| Geographical area | |||

| North | 2293 | 19 (15–27) | <0.001 |

| Middle | 5035 | 18 (13–24) | |

| South | 4257 | 15 (12–20) | |

| Disease name as diagnosed at emergency departments | |||

| Cardiopulmonary arrest | 3678 | 15 (12–19) | <0.001 |

| External cause | |||

| Trauma | 1164 | 22 (16–31) | <0.001 |

| Burn injury | 43 | 23 (18–30) | <0.001 |

| Intoxication | 160 | 23 (18–30) | <0.001 |

| Other external cause* | 163 | 18 (14–24) | 0.26 |

| Internal cause | |||

| Central neurological disease | 1536 | 18 (14–23) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory disease | 1436 | 18 (14–25) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1431 | 16 (12–22) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 756 | 18 (14–25) | <0.001 |

| Renal and urogenital disease | 85 | 17 (13–20) | 0.88 |

| Other internal disease† | 1142 | 19 (15–26) | <0.001 |

| Minor disease‡ | 172 | 20 (14–29) | <0.001 |

*Other external causes include heat stroke, hypothermia, hanging, asphyxia, drowning and foreign body in an airway.

†Other internal causes included disturbance of consciousness and shock of unknown origin, haematological disease, immunological disease, endocrine metabolic disease and neuromuscular disease.

‡Minor diseases included eye disease, skin disease, nose and throat disease, obstetrical and gynaecological disease, psychiatric disorders, breast disease and orthopaedic disease (except trauma).

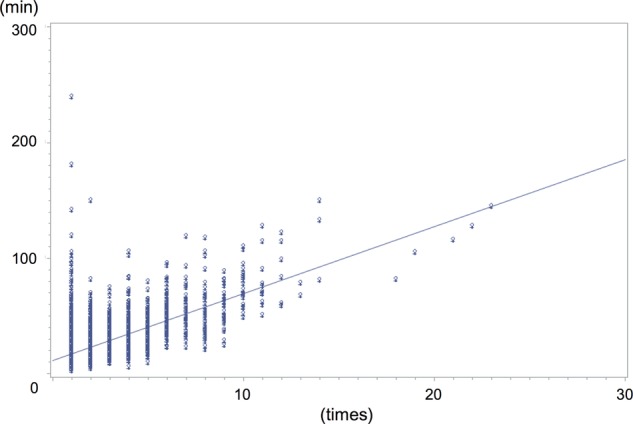

Figure 2 shows the relationship between on-scene time and the number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel. The more phone calls that were made, the longer was the on-scene time—hence, a strong correlation between the two (Pearson correlation coefficient: 0.57, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

The relationship between on-scene time and number of phone calls to hospitals from emergency medical service personnel.

The results of the multivariable logistic regression for on-scene time over 30 min are shown in table 3. The number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel, intoxication, minor disease and geographical area were the main factors associated with on-scene times over 30 min. The number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel had a higher OR per phone call (phone calls to hospitals: OR 2.57, p<0.001). Intoxication and minor diseases had higher ORs than the other diseases (intoxication: OR 1.82, p=0.011, minor disease: OR 1.65, p=0.023). As for geographical area, the north and middle areas had higher ORs than the south (the north: OR 3.20, p<0.001, the middle: OR 2.20, p=0.03). Age, gender, day of week, and time of the day had no relationship with on-scene times over 30 min.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis for on-scene time over 30 min

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | 0.32 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.05) | 0.22 |

| Disease name as diagnosed at emergency departments | ||

| Cardiopulmonary arrest | 0.30 (0.24 to 0.38) | <0.001 |

| Trauma | 1.19 (0.94 to 1.51) | 0.15 |

| Intoxication | 1.82 (1.15 to 2.87) | 0.011 |

| Other external cause | 0.58 (0.33 to 1.02) | 0.058 |

| Central neurological disease | 0.48 (0.37 to 0.61) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory disease | 0.63 (0.49 to 0.80) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.37 (0.28 to 0.48) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 0.68 (0.51 to 0.91) | 0.010 |

| Minor disease | 1.65 (1.06 to 2.57) | 0.023 |

| Time of the day | ||

| Night shift | 1.15 (0.96 to 1.36) | 0.068 |

| Evening shift | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.15) | 0.24 |

| Day shift | 1.00 | |

| Phone calls to hospitals | 2.57 (2.43 to 2.72) | <0.001 |

| Geographical area | ||

| North | 3.20 (2.65 to 3.87) | <0.001 |

| Middle | 2.20 (1.85 to 2.61) | 0.003 |

| South | 1.00 | |

Discussion

Key findings

In this study, we found that with regard to ambulance transportation for critical emergency patients in a big city in Japan, the number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel, intoxication, minor disease and geographical area were factors related to prolonged on-scene times over 30 min.

Relationship to previous studies

Our results are in accordance with a number of observational studies in Japan that have reported that on-scene time increased with the number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel regardless of the severity of illness.7–9 Kitamura et al9 reported that the more phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel that were made, the longer was the on-scene time for patients with acute myocardial infraction. One prospective population-based cohort study reported that, in Japan, on-scene time is particularly prolonged for suspected drug overdose patients because of the time to obtain acceptance from hospitals to care for them.10 A population-based observational study, again from Japan, showed that on-scene time of psychiatric emergency services was statistically longer than that of other emergency services.11 In our study, intoxication was related to prolonged on-scene time over 30 min, and three quarters of those intoxicated patients were suffering from drug overdose and likely to have psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, psychiatric disorders were included in our minor disease category, and this category was also related to prolonged on-scene times over 30 min. These findings suggest that on-scene times for drug overdose patients and those with psychiatric disorders were longer even in critical cases.

However, a few studies appear to contradict our results regarding geographical area, patient age and gender, and time of the day.11–14 Although our results showed that geographical area was associated with prolonged on-scene time over 30 min, a population-based observational study in Canada showed that there was no relation between on-scene time and the area of the city where the study took place. They reported that significant predictors of prolonged on-scene time for patients with chest pain were age, gender and the presence of an advanced life support (ALS) crew.12 In Japan, to the best of our knowledge, no study has shown the relationship between the geographical area of a city and on-scene time. One reason for the discrepancy between our finding and the Canadian study could well be the fundamental differences of the EMS systems in North America and Japan. In North America, all emergency patients are transferred to EDs in hospitals that provide emergency medicine, where emergency physicians see the emergency patients regardless of their symptoms or severity of their illnesses. On the other hand, in Japan, emergency patients are transferred to hospitals which the EMS personnel select on the basis of the severity of illnesses of patients, which requires the EMS personnel to call ahead to appropriate hospitals to ask if they can accommodate the patient. Another reason for the discrepancy between our result and those of the other study could well be due to the differences in the emergency medical systems of hospitals in Japan. For example, at some hospitals, the emergency physicians get a call directly from the EMS personnel, and at other hospitals, information clerks or nurses receive the call first and then ask each medical specialist if he/she can see and treat the emergency patient. Therefore, the talk time between the EMS personnel and the hospital in this latter case is likely to be longer than in the former case. Furthermore, in Japan, there are regional differences in the EMS and treatment offered at different hospitals. Several studies, for example, have reported differences in on-scene time between metropolitan cities and rural areas, and the survival outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest among seven different geographic regions of the country.14–16 Similar to Kawasaki city, it is possible that the differences in the emergency medical systems of tertiary care emergency centres and acute care hospitals in Kawasaki city affect on-scene time of geographical area.

In our study, using multivariable logistic regression, we found that age, gender and time of the day were not related to on-scene times over 30 min. However some previous studies have shown that age (per decade), gender (female) and time of the day (night shift) were related to prolonged on-scene time.11–14 These differences might be caused by differences in study population, outcome variables, statistical analysis and covariates. Our study included only critical patients, defined the outcome variable as on-scene time over 30 min, and conducted multivariable statistical analysis for the outcome variable. The influence of age, gender and time of the day on on-scene time may decrease in more specific cases as in our study.

Significance and implications

A survey made by the Japanese Fire and Disaster Management Agency reports that the number of patients transported by ambulances has increased year by year. The number of patients transported by ambulances in 2012 was 5.25 million people, the highest number ever, and an increase of 67 thousand people from 2011.1 A possible cause for this increase could be a rise in the number of mild and moderately ill patients who were transported by ambulances.1 However, in Japan, there is a concurrent annual decrease in the number of emergency medical facilities which will accept such patients.17 Therefore, mild and moderately ill patients may be transported to tertiary care hospitals, which may affect on-scene time for EMSs to transport critical patients due to overcrowding.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to focus on prolonged on-scene time of ambulance transportation for critical emergency patients in a big city. The results of our study showed that in a big city the difference in geographical area affected on-scene time over 30 min for critical patients. It also showed that intoxication and the number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel were related to prolonged on-scene time, even for critical patients.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, our results are considered to be useful with regard to big cities in Japan, as a few studies conducted in other big cities have reported similar results.7–10 However, our results may not adapt to rural districts and other countries. This study would be useful for big cities in other countries because they might enhance the welfare as universal coverage and free service for ambulance like Japan in future. Second, this study's participants were critical patients who had various diseases because illness-specific, injury mechanism-specific and on-scene specific aspects could affect on-scene time. Third, it is possible that our study population might include patients who were not critical, due to the fact that the definition of a critical patient used in this study (those who are expected to be hospitalised for more than 3 weeks or are confirmed dead by a doctor), in accordance with the national criteria, is somewhat vague. Fourth, the severity of a patient's condition might not reflect the severity at that time when the ambulance was called, because the assessment of the severity of the patient's condition was conducted after arrival at the hospital. Some patients might deteriorate during transportation and be assessed as critically ill at the hospitals. Therefore, it is possible that some patients in our study were misclassified, and further study is perhaps needed with a more defined selection of symptom severity.

Conclusions

Our study, based in a big city in Japan, has shown that for ambulance transport for critical emergency patients the number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel, intoxication, minor diseases and geographical area were factors related to prolonged on-scene times of over 30 min. To reduce on-scene time, it is vital to redesign our emergency system and important to develop a system that accommodates critical patients with intoxication and minor diseases and furthermore to reduce the number of phone calls to hospitals from EMS personnel.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Kawasaki Fire Department, and Thomas D Mayers for his English language manuscript revision.

Footnotes

Contributors: IN collected the data, conceived the study, participated in its design and performed the statistical analysis, and also wrote the manuscript. TA contributed to the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. YN and NT contributed to the design of the study and critically revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (H27-seisaku-senryaku-012).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee of Teikyo University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (2012). (Retrieved 25 Feb 2015). http://www.fdma.go.jp/neuter/topics/houdou/h25/2512/251218_1houdou/01_houdoushiryou.pdf (In Japanese).

- 2.Kosaka S, Yoshioka T. Importance of emergency transport for patients with acute cardiac failure: the relationship between arrival time at hospital and short-term prognosis. ICU CCU 2010;34:833–4 (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly AM, Kerr D, Patrick I et al. . Call-to-needle times for thrombolysis in acute myocardial infraction in Victoria. Med J Aust 2003;178:381–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamila SF, John AP, Jacob S. On-scene time and outcome after penetrating trauma: an observational study. Emerg Med J 2011;28:797–801. 10.1136/emj.2010.097535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohama A. Worrisome phenomenon of EMS system in metropolitan areas—the ambulance times from call to hospital are prolonged. JJSEM 2007;10:509–16 (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawasaki City. Retrieved 5 March 2015. http://www.city.kawasaki.jp/shisei/category/51-43-3-0-0-0-0-0=0.html, http://www.city.kawasaki.jp/200/page/0000009567.html (In Japanese).

- 7.Ito T, Takei T, Fujisawa M et al. . Analysis of the rejection of transportation to other hospitals before coming to our hospital. JJSEM 2010;13:1–7 (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto T, Suzuki N, Imaki S et al. . Present condition of transportation for patients calling for emergency medical service in Yokohama city and its problem. JJSEM 2011;14:1–6 (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T et al. . Ambulance calls and prehospital transportation time of emergency patients with cardiovascular events in Osaka City. Acute Med Surg 2014;1:135–44. 10.1002/ams2.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubota Y, Hasegawa K, Taguchi H et al. . Characteristics and trends of emergency patients with drug overdose in Osaka. Acute Med Surg 2015;2:237–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurosawa N, Kimura T, Arima K et al. . The survey about the stay time of psychiatric related emergency in the eastern Saitama area. JJSEM 2013;16:671–6 (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schull MS, Morrison LJ, Vermeulen M et al. . Emergency department overcrowding and ambulance transport delays for patients with chest pain. CAMJ 2003;168:277–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan AL, Beshansky JR, Ruthazer R et al. . Factors associated with longer time to treatment for patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes: a cohort study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:86–94. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumada K, Toyoda I, Ogura S et al. . The relationship between the EMS transportation time and the number of emergency facilities; Situation of two city. JJSEM 2011;14:431–6 (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsubouchi I, Kohama A, Sakurai A et al. . Comparison of emergency medical service (EMS) between rural area Tottori and capital city Tokyo. JJSEM 2010;13:487–92 (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasegawa K, Tsugawa Y, Camargo CA Jr et al. . Regional variability in survival outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the All-Japan Utstein Registry. Resuscitation 2013;84:1099–107. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare (2010). (Retrieved 5 March 2015). http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/hoken/kiso/21.html (In Japanese).