Abstract

A 68-year-old man experienced a right caudate haemorrhage with intraventricular haemorrhage. Although a subarachnoid haemorrhage was not shown clearly, our investigation demonstrated an aneurysm-like vascular pouch located in the anomalous vessel arising from the A2 segment of the right anterior cerebral artery. Rupture of the vascular pouch was considered to be the cause of the caudate haemorrhage. Neck clipping was performed. In intraoperative observation, the anomalous vessel was diagnosed as a right accessory middle cerebral artery. Histopathology of the saccular wall showed only an adventitia and a fibrin layer, indicating a pseudoaneurysm. We routinely perform detailed vascular evaluation for any cerebrovascular disease. A meticulous vascular survey makes it possible to obtain valuable clues in cases such as caudate haemorrhage due to pseudoaneurysm of the accessory middle cerebral artery, leading to prevention of rebleeding.

Background

The incidence of caudate haemorrhage is markedly less than that of haemorrhage of the putamen, thalamus, corticomedullary junction or posterior fossa, and accounts for 0.1–7.0% of all cases of spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage.1 Although hypertension is a major risk factor for caudate haemorrhage, aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation or moyamoya disease are also potential causes.1 The caudate nucleus receives blood supply from the recurrent artery of Heubner, the anterior lenticulostriate arteries and the lateral lenticulostriate arteries.2 The accessory middle cerebral artery (MCA) is a variation of the MCA and, according to Teal's classification, which is widely accepted for variations of the MCA, originates from the A1 or proximal A2 segment of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA).3 4 The frequency of accessory MCA is reported to be 0.3–2.7% of autopsy series and 0.26–4% of angiographical studies.3 Accessory MCA coexists with the recurrent artery of Heubner, and it reaches the anterior perforated substance.3 Therefore, a vascular event in the proximal portion of the accessory MCA may result in a stroke in the caudate. We present a case of caudate haemorrhage caused by a ruptured pseudoaneurysm of the accessory MCA, which was treated by surgical intervention. Although there are a few reports of aneurysm of the accessory MCA, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case describing the relationship between rupture of the accessory MCA and caudate haemorrhage.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old man was initially admitted to a local hospital because of a disturbance in consciousness and vomiting. Neurological examination on admission was Hunt and Kosnik grade 3 without motor weakness. He had no health problems and no family medical history. The patient was diagnosed as having caudate haemorrhage, and referred to our hospital for further treatment after receiving conservative care. On examination, he was fully conscious without any focal neurological deficits.

Investigations

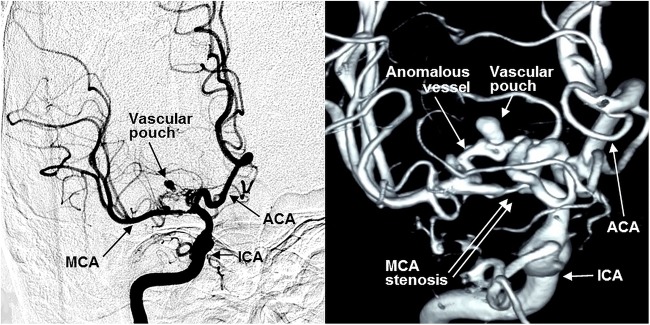

CT on the first admission demonstrated a haematoma in the right caudate nucleus with intraventricular haemorrhage. A subarachnoid haemorrhage was not clearly visualised (figure 1). In our hospital, CT angiography (CTA) showed an aneurysm-like vascular pouch located in the anomalous vessel arising from the right ACA. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) revealed a stenosis of the M1 segment of the right MCA, and an anomalous vessel originating from the proximal portion of the A2 segment of the right ACA, which coursed parallel to the MCA and continued to the cortical area (figure 2). Furthermore, a vascular pouch 7 mm in diameter was demonstrated in the anomalous vessel (figure 2).

Figure 1.

CT scans on the first admission showing a right caudate haemorrhage with intraventricular haemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage, which was not clearly demonstrated (R, right).

Figure 2.

Preoperative right internal carotid angiograms revealing a stenosis of the M1 segment of the right MCA; the anomalous vessel originated from the A2 segment of the right ACA with an aneurysm-like vascular pouch (ICA, right internal carotid artery; ACA, right anterior cerebral artery; MCA, right middle cerebral artery).

Treatment

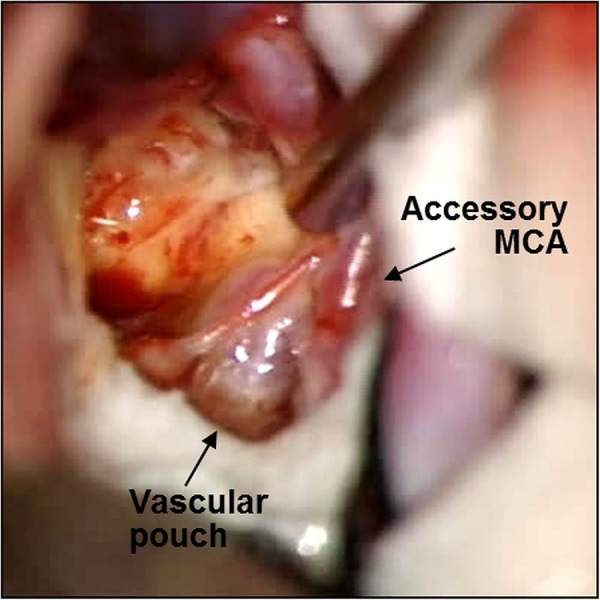

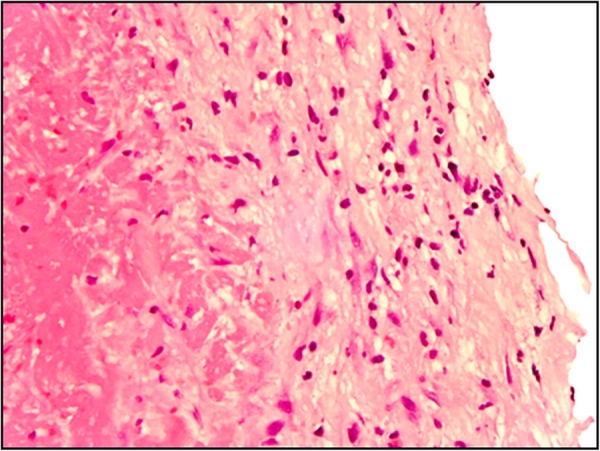

The location of the haematoma and the vascular pouch were so close that the cause of the haemorrhage was considered to be rupture of the vascular pouch. We decided that the vascular pouch should be treated because of a high risk of rebleeding. A trans-sylvian approach with frontotemporal craniotomy was performed. The MCA was identified, and several branches of the MCA exhibited atherosclerotic changes. After removal of the old haematoma in the base of the right frontal lobe, the vascular pouch harbouring the anomalous vessel was located. In intraoperative observation, the recurrent artery of Heubner was also confirmed, so that this anomalous vessel was identified as an accessory MCA from its origin and its course. Part of the saccular wall was dark red, indicating partial thrombosis (figure 3). After clipping the origin of the vascular pouch, the wall of the pouch was partially resected. Histopathological examination revealed that the wall of the vascular pouch was partly thrombosed and consisted of an adventitia and a fibrin layer without intima, internal elastic membrane and media (figure 4). These histopathological features indicated that this vascular pouch was a pseudoaneurysm.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative photograph showing a dark red wall on part of the vascular pouch, indicating partial thrombosis (Accessory MCA, right accessory middle cerebral artery).

Figure 4.

Histopathological photomicrograph of the saccular wall demonstrating that the arterial layer was only an adventitia and a fibrin without intima, internal elastic membrane and media. H&E stain, magnification ×400.

Outcome and follow-up

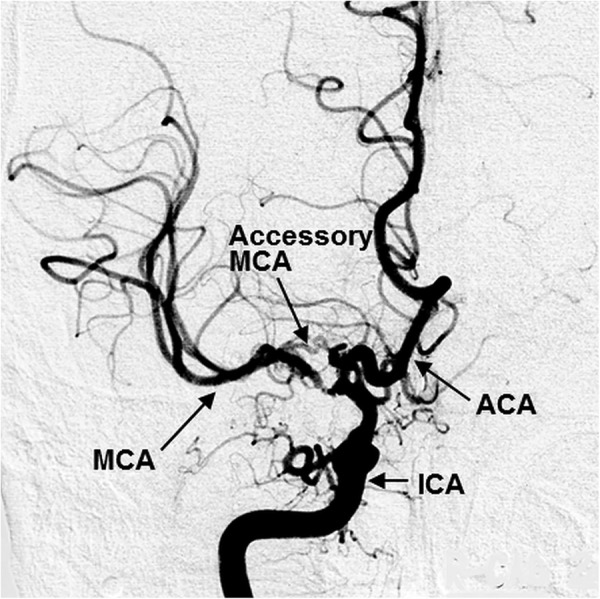

Postoperative angiography showed disappearance of the vascular pouch with preserved patency of the right accessory MCA (figure 5). The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on foot.

Figure 5.

Postoperative right internal carotid angiogram showing patency of the right accessory MCA and exclusion of the vascular pouch (ICA, right internal carotid artery; ACA, right anterior cerebral artery; MCA, right middle cerebral artery; Accessory MCA, right accessory middle cerebral artery).

Discussion

In 1973, Teal et al4 suggested that the term, ‘accessory middle cerebral artery’, given by Crompton et al, referred to an anomalous vessel arising from the ACA and running parallel to the MCA. The accessory MCA can coexist with the recurrent artery of Heubner, and also runs laterally into the sylvian fissure, unlike the recurrent artery of Heubner, which enters into the anterior perforated substance.5 In Teal's classification, the accessory MCA usually originating from the A1 or proximal A2 segment of the ACA provides the territory of the orbitofrontal, prefrontal, precentral and/or central arteries.3 4 Although it is generally smaller than the MCA, there are abundant anastomoses between the accessory MCA and the major trunk of the MCA.6 Therefore, the accessory MCA may serve as a collateral blood supply to the rest of the MCA territory.7 In the present case, stenosis of the M1 segment might have caused the accessory MCA to provide additional collateral blood flow to the MCA territory. The accessory MCA aneurysm is so rare that only 12 cases, including ours, have been reported in the literature.8 Haemodynamic stress has been suggested to lead to formation of an aneurysm, including a pseudoaneurysm.9 The recurrent blood flow from the A1 segment of the ACA to the accessory MCA may have produced haemodynamic stress.8 The present case may have exhibited haemodynamic stress induced by the severe stenosis in the M1 segment, resulting in increased blood flow to the accessory MCA. The pseudoaneurysm may have resulted from the haemodynamic stress that affected the accessory MCA. All the reported cases of ruptured accessory MCA aneurysm presented with subarachnoid haemorrhage.8 However, in the present case, the subarachnoid haemorrhage was not shown clearly and the caudate haemorrhage was strongly visualised. Most caudate haemorrhage occurs in the penetrating arteries of the ACA or MCA,10 with no reports of accessory MCA rupture as a cause of caudate haemorrhage. Although caudate haemorrhage and accessory MCA are rare, our data suggest that they can coexist. In our hospital, because vascular evaluation such as CTA and DSA is routinely performed for any cerebrovascular disease including intracerebral haemorrhage, it was possible to obtain this valuable case. In a typical haematoma in the basal ganglia, meticulous vascular survey should be performed, and any vascular anomaly should be treated.

Learning points.

Although caudate haemorrhage and accessory middle cerebral artery are both rare, they can coexist, and caudate haemorrhage is caused by rupture of the accessory middle cerebral artery.

The pseudoaneurysm develops in the accessory middle cerebral artery associated with a stenosis of the middle cerebral artery.

In a typical cerebral haemorrhage, a meticulous vascular survey is important to prevent rebleeding.

Footnotes

Contributors: ST was responsible for the conception, design and interpretation of this report. JT, YN and TY participated in drafting and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Liliang PC, Liang CL, Lu CH et al. Hypertensive caudate hemorrhage prognostic predictor, outcome, and role of external ventricular drainage. Stroke 2001;32:1195–200. 10.1161/01.STR.32.5.1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumral E, Evyapan D, Balkir K. Acute caudate vascular lesions. Stroke 1999;30:100–8. 10.1161/01.STR.30.1.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reis CV, Zabramski JM, Safavi-Abbasi S et al. The accessory middle cerebral artery: anatomic report. Neurosurgery 2008;63(1 Suppl 1):ONS10–13; discussion ONS13-14 10.1227/01.neu.0000335005.99756.eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teal JS, Rumbaugh CL, Bergeron RT et al. Anomalies of the middle cerebral artery: accessory artery, duplication, and early bifurcation. AM J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1973;118:567–75. 10.2214/ajr.118.3.567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi S, Hoshino F, Uemura K et al. Accessory middle cerebral artery: is it a variant form of the recurrent artery of Heubner? AJNR 1989;10:563–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain KK. Some observations on the anatomy of the middle cerebral artery. CJS 1964;7:134–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komiyama M, Nishikawa M, Yasui T. The accessory middle cerebral artery as a collateral blood supply. AJNR 1997;18:587–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakabayashi Y, Hori Y, Kondoh Y et al. Ruptured anterior cerebral artery aneurysm at the origin of the accessory middle cerebral artery. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2011;51:645–8. 10.2176/nmc.51.645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seki Y, Fujita M, Mizutani N et al. Spontaneous middle cerebral artery occlusion leading to moyamoya phenomenon and aneurysm formation on collateral arteries. Surg Neurol 2001;55:58–62; discussion 62 10.1016/S0090-3019(00)00339-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung CS, Caplan LR, Yamamoto Y et al. Striatocapsular haemorrhage. Brain 2000;123:1850–62. 10.1093/brain/123.9.1850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]