Abstract

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head is a rare complication related to glucocorticoid administration and traditionally has been associated with high doses and/or prolonged therapy. Occurrence of osteonecrosis with a physiological replacement dose of glucocorticoids has not been reported previously. We report a 38-year-old man with non-secreting pituitary adenoma who developed bilateral AVN while on a very small dose of oral prednisolone for secondary adrenal insufficiency after surgery for pituitary adenoma. The patient was switched to hydrocortisone. Zolindronic acid was administered and the patient underwent bilateral core decompressive surgery resulting in a reduction of hip pain and improvement. When last evaluated, 2 years after diagnosis of AVN, the patient was functionally independent, and was able to do his routine activities with mild pain. The report intends to highlight the occurrence of AVN of the femur even with a very small dose of prednisolone used for treatment of panhypopituitarism. Glucocorticoids may have to be continued in the lowest possible dose using the most physiological preparation such as hydrocortisone when stoppage is not possible.

Background

Avascular necrosis (AVN) is also known as aseptic necrosis or osteonecrosis. It occurs in approximately 3–40% of patients receiving corticosteroids with the most common site of involvement being the femoral head, resulting in severe morbidity.1 2 This adverse complication is believed to be the result of limited blood supply to this area with death of bone tissue in the femoral head, leading to pain, limited mobility, fractures and in about 80% of untreated cases collapse of the femoral head requiring surgical management.1 3 4 We present the occurrence of AVN in a patient on replacement doses of prednisolone for panhypopituitarism following surgery for non-functional pituitary adenoma.

Case presentation

A 38-year-old man with persistent headache and visual disturbances for 3 months was diagnosed to have non-functioning pituitary adenoma of 26×22×12 mm size on MRI of the pituitary. Automated perimetry revealed bitemporal hemianopia. Surgical resection of the tumour through trans-sphenoidal pituitary surgery resulted in improvement in vision and resolution of bitemporal hemianopia. The patient had also received oral dexamethasone at a dose of 2 mg/day for less than a month before surgery. He did not follow-up for 2 months either in the surgery or endocrine unit. Two months after surgery, he presented with persistent fatigue, hypotension, anorexia and weight loss.

Investigations

On investigative workup, morning cortisol was<4 µg/dL. Biochemical investigations were significant for associated secondary hypothyroidism and hypogonadism (table 1). Symptoms improved with initiation of oral prednisolone which was given at a dose of 7.5 mg and later reduced to 5 mg daily. Levothyroxine was initiated 2 weeks later, initially at 50 μg/day and later increased to 100 µg/day. Injectable testosterone was also initiated at a dose of 100 mg 4 weekly as intramuscular injections.

Table 1.

Hormonal analysis of patient at the time of presentation

| Tests (normal range) | Reports |

|---|---|

| Free T3 (2–4.4 pg/mL) | 2.3 mg/mL |

| Free T4 (0.6–2.2 ng/dL) | 0.8 ng/mL |

| TSH (0.5–5 mIU/L) | 2.1 mIU/L |

| LH (1.8–7.8 mIU/L) | 1.4 mIU/mL |

| FSH (1.55–9.7 mIU/L) | 3.2 mIU/mL |

| Testosterone (4.5–28.2 nmol/L) | 0.48 nmol/L |

| Serum cortisol | <4 µg/dL |

FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinising hormone; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Two years after the initiation of hormone replacement, the patient noticed insidious onset pain in the medial aspect of bilateral thighs that gradually worsened with progressive difficulty in walking leading to limping. X-ray of the bilateral hip and MRI of soft tissue hips revealed bilateral AVN of the femoral head (right>left) (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior view of the pelvis showing a flattening of the outer portion of the right femoral head from avascular necrosis (arrow), with adjacent joint space narrowing.

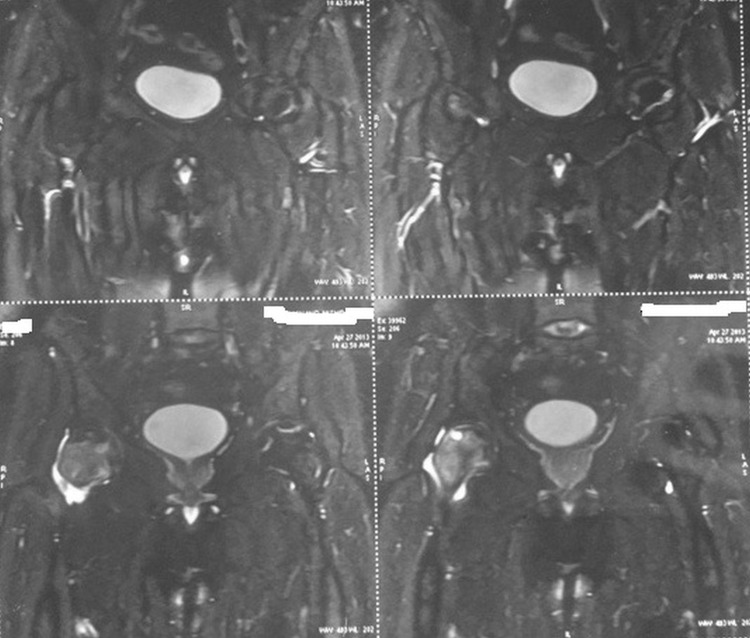

Figure 2.

MRI of the bilateral hip showing avascular necrosis of femoral heads with the right side affected more than the left side.

Treatment

Oral prednisone was replaced by hydrocortisone as it is believed to be the more physiological preparation of glucocorticoids at a lower dose of 10 mg in the morning (7:00) and 5 mg in the late afternoon (15:00) with counselling for increasing the dose during stress. The patient underwent core decompression surgery, immobilisation and zolindronic acid 5 mg administration along with calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient reported significant improvement in pain. When last evaluated, 2 years after diagnosis of AVN, the patient was functionally independent, and was able to do his daily activities with mild pain without analgesics. On further follow-up, he continued to require a low dose of oral hydrocortisone at a dose of 5 mg/day.

Discussion

AVN is one of the devastating complications of glucocorticoid therapy occurring in up to 40% of patients.1 The association between glucocorticoid use and osteonecrosis was first described in patients with a renal transplant who were on immunosuppression as part of the transplant regimen.1 5 Causes of AVN apart from trauma include conditions associated with hypercoagulable states, systemic lupus erythematosus, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, alcoholism and organ transplantation.5 These conditions put the patient at higher risk for developing AVN prior to the initiation of glucocorticoids. Most patients with AVN are incapacitated and may eventually require hip replacement. Corticosteroids affect almost every body system and its long-term use is associated with various well-established side effects, including AVN.6 7 Corticosteroids are also given as replacement therapy as our patient with hypopituitarism. The mechanism of steroid-induced AVN is due to a complex interplay and imbalance of bone resorption and formation, impairment of vasculature within bone and apoptosis.4 5

Powell et al8 reviewed 66 cases of steroid-induced AVN and found that the most commonly associated administered route included intravenous steroids followed by oral and rarely intramuscular, intra-articular injections and inhaled steroids. Karkoulias et al9 reported aseptic femoral head necrosis in a patient receiving long courses of inhaled and intranasal corticosteroids. The occurrence of AVN after steroid use appears to be dose related. A majority of the studies have shown an increased risk of AVN in patients receiving >20 mg/day of prednisone.

A meta-analysis of 22 studies conducted by Felson and Anderson10 suggested a 4.6-fold increase in incidence of AVN with every 10 mg/day increase in prednisone therapy in the first 6 months of corticosteroid therapy.10 Patton et al11 also noted that the mean linear trend of higher daily prednisolone dose was also statistically significant for the development of osteonecrosis. However, Dimant et al12 failed to find a correlation between peak dose, duration or cumulative dose of steroid and osteonecrosis.

Most cases of AVN due to oral prednisolone have been with doses ranging from 10 to 200 mg/day over a prolonged period ranging from 14 days to 20 years. We could come across only two cases of steroid-induced osteonecrosis where lower doses had been used. O'Brien and Mack13 reported AVN of the femoral head with oral prednisolone 5 mg/day over a prolonged duration of 10 years. However, this patient also received intra-articular cortisone injection. Another case was reported by Spencer et al14 where AVN of the femoral head occurred after 10 years of oral prednisone at 4 mg/day. This patient had also received intravenous methylprednisolone injection previously. As compared to these two patients, our patient developed AVN of the femoral head over a period of only 2 years. He also received supraphysiological doses of steroids for a short duration almost 2 years prior to the occurrence of AVN. It is difficult to say whether it was the cumulative doses of steroids that precipitated AVN in this particular case. Another unusual observation in our patient was bilateral involvement of femoral heads. Anecdotal case reports of steroid-induced bilateral AVN have been reported.8 15 Havel et al15also reported steroid-induced bilateral osteonecrosis of lateral femoral epicondyles with oral steroids.

The occurrence of osteonecrosis with such a low dose of corticosteroid was surprising. Tokuhara et al16 examined the relationship between osteonecrosis and steroid dose in white rabbits and they observed that low levels of steroid metabolising hepatic activity may increase responsiveness to steroids and further risk of steroid-induced osteonecrosis even with low steroid dose.

Hip replacement was not considered in our patient in view of improvement with conservative management, zolindronic acid and core decompression surgery. Bisphosphonates (alendronate) have been shown in two different studies to be helpful in delaying collapse of the femoral head and hence delaying the need for hip replacement.17

This report intends to highlight the occurrence of AVN of the femur even with a very small dose of glucocorticoid used for treatment of secondary hypocortisolism.

Learning points.

Any patient with hip pain even on a replacement dose of glucocorticoid should be evaluated to rule out avascular necrosis (AVN).

Stoppage of glucocorticoids may not always be possible.

In such situations, glucocorticoids need to be continued in the lowest possible dose using the most physiological preparation, viz hydrocortisone.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient for his cooperation and pray for his good health.

Footnotes

Contributors: PD and AA have clinically worked up the patient under the guidance of DD and BK. PD has written the case report under the guidance of BK and DD.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Assouline-Dayan Y, Chang C, Greenspan A et al. . Pathogenesis and natural history of osteonecrosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002;32:94–124. 10.1053/sarh.2002.33724b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seamon J, Keller T, Saleh J. The pathogenesis of nontraumaticosteonecrosis. Arthritis 2012;601763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstein RS. Glucocorticoid-induced osteonecrosis. Endocrine 2012;41:183–90. 10.1007/s12020-011-9580-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerachian MA, Seguin C. Glucocorticoids in osteonecrosis of femoral head: a new understanding of the mechanism of action. J Steroid Biochem Mol Bio 2009;114:121–8. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aaron RK, Voisinet A. Corticosteroid associated avascular necrosis: dose relationship and early diagnosis. Ann NY Acad Sci 2011;1240:38–46. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bialas MC, Routledge PA. Adverse effects of corticosteroids. Adverse Drug React Toxicol Rev 1998;17:227–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchman AL. Side effects of corticosteroid therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001;33:289–94. 10.1097/00004836-200110000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell C, Chang C, Naguwa SM et al. . Steroid induced osteonecrosis: an analysis of steroid dosing risk. Autoimmun Rev 2010;9:721–43. 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karkoulias K, Charokopos N, Kaparianos A et al. . Aseptic femoral head necrosis in a patient receiving long term courses of inhaled and intranasal corticosteroids. Tuberk Toraks 2007;55:182–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felson DT, Anderson JJ. Across-study evaluation of association between steroid dose and bolus steroids and avascular necrosis of bone. Lancet 1987;329:902–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)92870-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patton PR, Pfaff WW, Lieberman JR et al. . Aseptic bone necrosis after renal transplantation. Surgery 1988;103:63–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimant J, Ginzler EM, Diamond HS et al. . Computer analysis of factors influencing the appearance of aseptic necrosis in patients with SLE. J Rheumatol 1978;5:136–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Brien TJ, Mack GR. Multifocal osteonecrosis after short-term high-dose corticosteroid therapy. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992;279:176–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spencer JD, Humphreys S, Tighe JR et al. . Early avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Report of a case and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1986;68:414–17. 10.1002/bjs.1800730539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Havel PE, Ebraheim NA, Jackson WT. Steroid-induced bilateral avascular necrosis of the lateral femoral condyles. a case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989;243:166–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokuhara Y, Wakitani S, Oda Y et al. . Low levels of steroid-metabolizing hepatic enzyme (cytochrome P450 3A) activity may elevate responsiveness to steroids and may increase risk of steroid-induced osteonecrosis even with low glucocorticoid dose. J Orthop Sci 2009;14:794–800. 10.1007/s00776-009-1400-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGrory BJ, York SC, Iorio R et al. . Current practices of AAHKS members in the treatment of adult osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:1194–204. 10.2106/JBJS.F.00302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]