Abstract

Liver injury due to idiosyncratic drug reactions can be difficult to diagnose and may lead to acute liver failure (ALF), which has a high mortality rate. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is effective treatment for paracetamol toxicity, but its role in non-paracetamol drug-induced ALF is controversial. We report on the use of a validated bedside tool to establish causality for drug-induced liver injury (DILI) and describe the first case of resolution of norfloxacin-induced ALF after NAC therapy. NAC is easy to administer and generally has a good safety profile. We discuss the evidence to support the use of NAC in ALF secondary to DILI and possibilities for further clinical research in this field.

Background

Acute liver failure (ALF) has a high mortality rate and therapeutic options other than liver transplantation remain limited. Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury (DILI) accounts for 11% of ALF cases.1 Although N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is effective treatment for paracetamol toxicity, its role in non-paracetamol drug-induced ALF is controversial. We report the first case of resolution of norfloxacin-induced ALF after NAC therapy.

Case presentation

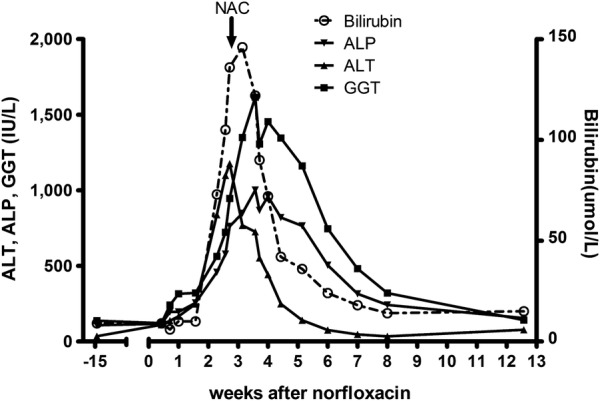

A 77-year-old woman was admitted to hospital for investigation of diarrhoea. Her medical history included hypertension and a mastectomy for breast cancer. Her regular medications were anastrazole, atenolol and olmesartan. She had taken 2 g norfloxacin (400 mg twice daily) starting 3 days before admission for suspected bacterial gastroenteritis. Stool analysis was normal and her diarrhoea resolved. LFTs were newly deranged (bilirubin 10 µmol/L, alanine aminotransferase 248 U/L, γ-glutamyltransferase 321 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 256 U/L). Full blood count and urea and electrolytes were normal. She became progressively jaundiced over 2 weeks (bilirubin 146 µmol/L, alanine transaminase 1176 U/L, γ-glutamyl transferase 1616 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 1002 U/L, figure 1). She had no history of liver disease and denied excessive alcohol intake.

Figure 1.

Liver function tests during the clinical course consistent with hepatitis and acute liver failure after norfloxacin treatment with slow resolution after administration of NAC. NAC, N-acetylcysteine; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, γ glutamyl transferase.

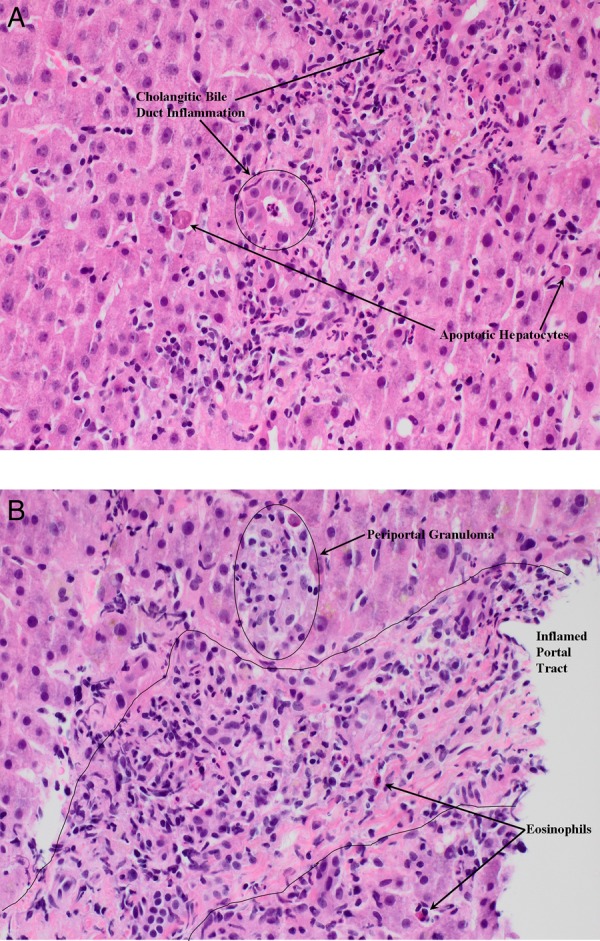

Initial liver screen was unremarkable; hepatitis A, B, C, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus serology were negative. Antismooth muscle antibodies, antiliver kidney microsomal antibodies, antinuclear antibodies and antimitochondrial antibodies were negative. Immunoglobulin profile, iron studies, caeruloplasmin, copper, paracetamol level and liver imaging (abdominal ultrasound with Doppler of portal and hepatic veins, and MR cholangiopancreatography) were normal. Because of worsening jaundice of uncertain aetiology, a liver biopsy was performed. Liver biopsy demonstrated acute hepatitis with centrilobular hepatocyte drop-out, ceroid-laden macrophages, pericholangitis/cholangitis (figure 2A), parenchymal and portal inflammation with eosinophilia (figure 2B). Using the Council for International Organisation of Medical Sciences scale for DILI causality,2 norfloxacin-induced hepatotoxicity was deemed ‘highly probable’.

Figure 2.

Liver biopsy demonstrated acute hepatitis with centrilobular hepatocyte drop-out, ceroid-laden macrophages, pericholangitis/cholangitis (A), parenchymal and portal inflammation with eosinophilia (B).

The patient developed ALF with low-grade encephalopathy and impaired synthetic function (international normalised ratio (INR) 2.7). The State liver transplant unit was contacted and they advised NAC administration, given as an 18 g/24 h infusion over 2 days. The patient's encephalopathy resolved, LFTs improved (figure 1) and INR normalised, although it was 3 months before LFTs completely normalised.

Discussion

DILI is a heterogeneous condition and can lead to ALF or death.3 It is most commonly due to antibiotics, and treatment options are limited. Although there are only five published cases of severe norfloxacin-induced hepatoxicity,4–8 numerous reports of DILI due to other fluoroquinolones demonstrate a likely ‘class effect’ with short latency to DILI and prominent eosinophils on liver biopsy.9 The prevalence of norfloxacin-induced liver injury may be higher than published data suggest, as 48 other probable or possible cases of liver injury caused by norfloxacin have been reported to the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration alone since 1988, with liver failure leading to transplantation in one case and death in another (personal correspondence, Department of Health, Australian Federal Government). However, attributing causality in suspected DILI can be difficult and misdiagnosis is common.2 The liver-specific Council for International Organisation of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) scale for DILI causality used in this case report has been validated for hepatoxicity and can be used prospectively as a bedside tool by the attending clinician rather than relying on expert opinion.2

ALF has a high mortality rate and therapeutic options other than liver transplantation remain limited. Although NAC is effective treatment for paracetamol toxicity, its role in non-paracetamol drug-induced ALF is not as well-established. There have been no prospective studies of NAC therapy in ALF specifically due to DILI, but some extrapolation can be made from studies of NAC administration in non-paracetamol induced ALF (which includes DILI and other ‘non-paracetamol’ causes of ALF). A prospective double-blinded randomised study in adults with non-paracetamol induced ALF demonstrated improved transplant-free survival after NAC therapy,10 with greatest benefit in those with low-grade encephalopathy and those with ALF due to DILI or hepatitis B. However, a recent randomised controlled study of children with non-paracetamol induced ALF demonstrated poorer transplant-free survival after NAC compared with placebo.11 The conflicting outcomes of these studies may be explained by the fact that DILI and hepatitis B, the aetiologies with the most favourable outcome after NAC in adults, were uncommon aetiologies in the paediatric study. There are also a number of case reports describing successful treatment of ALF due to DILI with NAC, but there are no previous reports of its use in hepatotoxicity due to norfloxacin.12 Additionally, NAC has been used for the treatment of ALF secondary to carbon tetrachloride, chloroform, penny royal oil, iron and ethanol toxicities, as well as hepatitis A, dengue fever and ischaemic hepatitis.12 13

ALF due to idiosyncratic DILI has a poor prognosis with the only prospective multicentre study of this patient group (none of whom received NAC) reporting transplant-free survival and overall survival of 27% and 66%, respectively.1 Multiple factors contribute to the pathogenesis of DILI, including formation of reactive drug metabolites, oxidative stress, and induction of signalling pathways and proinflammatory cytokines.14 NAC may provide benefit in DILI by targeting these mechanisms since it has been shown to improve oxygenation of the liver, has antioxidant properties and may attenuate the proinflammatory ‘cytokine storm’.14 15 NAC is relatively simple to administer in a standard hospital setting, and is generally well-tolerated and safe, with only rare reports of anaphylactoid reactions.12 We believe that NAC may be considered for ALF due to idiosyncratic DILI if transplantation is not possible or for patients in a non-transplant centre while awaiting transplantation. However, a large prospective randomised study of NAC as first-line therapy for ALF secondary to DILI is required in order to confirm its efficacy and safety in this context, as well as to define optimal dose and duration of therapy.

Learning points.

Norfloxacin and other fluoroquinolones are commonly prescribed antibiotics that can, rarely, cause acute liver failure.

The CIOMs scale is a bedside tool that can be used to determine drug-induced liver injury (DILI) causality.

N-acetylcysteine is a generally safe and potentially effective treatment for acute liver failure due to DILI.

Footnotes

Contributors: TRE was the patient's treating clinician, acquired and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. TS was the reporting pathologist who provided and described the liver histology images. GK was the patient's treating clinician and critically appraised the manuscript. PA is the Director of the Liver Transplant Unit, and provided clinical advice and critical appraisal of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM. Drug-induced acute liver failure: results of a US multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology 2010;52:2065–76. 10.1002/hep.23937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teschke R, Wolff A, Frenzel C et al. . Drug and herb induced liver injury: Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences scale for causality assessment. World J Hepatol 2014;6:17–32. 10.4254/wjh.v6.i1.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leise MD, Poterucha JJ, Talwalkar JA. Drug-induced liver injury. Mayo Clin Proc 2014;89:95–106. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björnsson E, Olsson R, Remotti H. Norfloxacin-induced eosinophilic necrotizing granulomatous hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:3662–4. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davoren P, Mainstone K. Norfloxacin-induced hepatitis. Med J Aust 1993;159:423, 426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero-Gomez M, Suarez-Garcia E, Fernandez MC. Norfloxacin induced acute cholestatic hepatitis in a patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:2324–5. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.02324.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez-Navidae A, Dimingo P, Cadasaleh J et al. . Norfloxacin-induced hepatotoxicity. J Hepatol 1990;11:277–8. 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90125-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucena MI, Andrade RJ, Sanchez-Martinez H et al. . Norfloxacin-induced cholestatic jaundice. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:2309–11. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.02309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orman ES, Conjeevaram HS, Vuppalanchi R et al. . Clinical and histopathologic features of fluoroquinolone-induced liver injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:517–23.e3. 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee WM, Hynan LS, Rossaro L et al. . Intravenous N-acetylcysteine improves transplant-free survival in early stage non-acetaminophen acute liver failure. Gastroenterology 2009;137:856–64. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Squires RH, Dhawan A, Alonso E et al. . Intravenous N-acetylcysteine in pediatric patients with nonacetaminophen acute liver failure: a placebo-controlled clinical trial. Hepatology 2013;57:1542–9. 10.1002/hep.26001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sales I, Dzierba AL, Smithburger PL et al. . Use of acetylcysteine for non-acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Ann Hepatol 2013;12:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison PM, Wendon JA, Gimson AE et al. . Improvement by acetylcysteine of hemodynamics and oxygen transport in fulminant hepatic failure. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1852–7. 10.1056/NEJM199106273242604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephens C, Andrade RJ, Lucena MI. Mechanisms of drug-induced liver injury. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;14:286–92. 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bémeur C, Vaquero J, Desjardins P et al. . N-acetylcysteine attenuates cerebral complications of non-acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure in mice: antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Metab Brain Dis 2010;25:241–9. 10.1007/s11011-010-9201-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]