An average of 25,900 cases of human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers are newly diagnosed in the United States each year.1,2 An estimated 14 million people are newly infected with HPV each year, and nearly half of these infections occur in people aged 14–25 years.3 Although most infections resolve over time, persistent infection with oncogenic HPV types is associated with a variety of cancers. Virtually all cervical cancers are caused by HPV, along with 90% of anal, 69% of vaginal, 60% of oropharyngeal, 51% of vulvar, and 40% of penile cancers.1 Furthermore, 87% of anal, 76% of cervical, 60% of oropharyngeal, 55% of vaginal, 44% of vulva, and 29% of penile cancers are caused by oncogenic HPV type 16 or 18.4 Of the 35,000 HPV cancers reported in 2009 in the United States, 39% occurred in males.1

Three HPV vaccines are currently available in the United States. One is a bivalent vaccine (designated as HPV2) designed to protect against HPV types 16 and 18, which are responsible for the most HPV-associated cancers. One is a quadrivalent vaccine (HPV4), which protects against HPV types 16 and 18 and two additional types, 6 and 11, that are the most common causes of genital warts. One is a nonavalent vaccine (HPV9) that protects against HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18, and offers additional protection against five oncogenic HPV types, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58. To prevent cancers associated with HPV infections, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends HPV immunization for all children aged 11 or 12 years with the licensed three-doses series. The ACIP has recommended routine HPV immunization for girls since 2006 and for boys since 2011.2

Despite ACIP's recommendations, rates of vaccination have remained low. In 2013, initiation rates for the HPV vaccine series were just 57.3% for girls and 34.6% for boys, and completion rates were <40% for girls and 15% for boys.2 These completion rates are well below the national Healthy People 2020 target of 80%.

CHARGE TO THE NATIONAL VACCINE ADVISORY COMMITTEE

To address the currently low HPV vaccination coverage rates, the Assistant Secretary for Health (ASH) charged the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) to review the current state of HPV immunization, to understand the root cause(s) for the observed relatively low vaccine uptake (both initiation and series completion), and to identify existing best practices, all with a goal of providing recommendations on how to increase use of this vaccine in young adolescents.

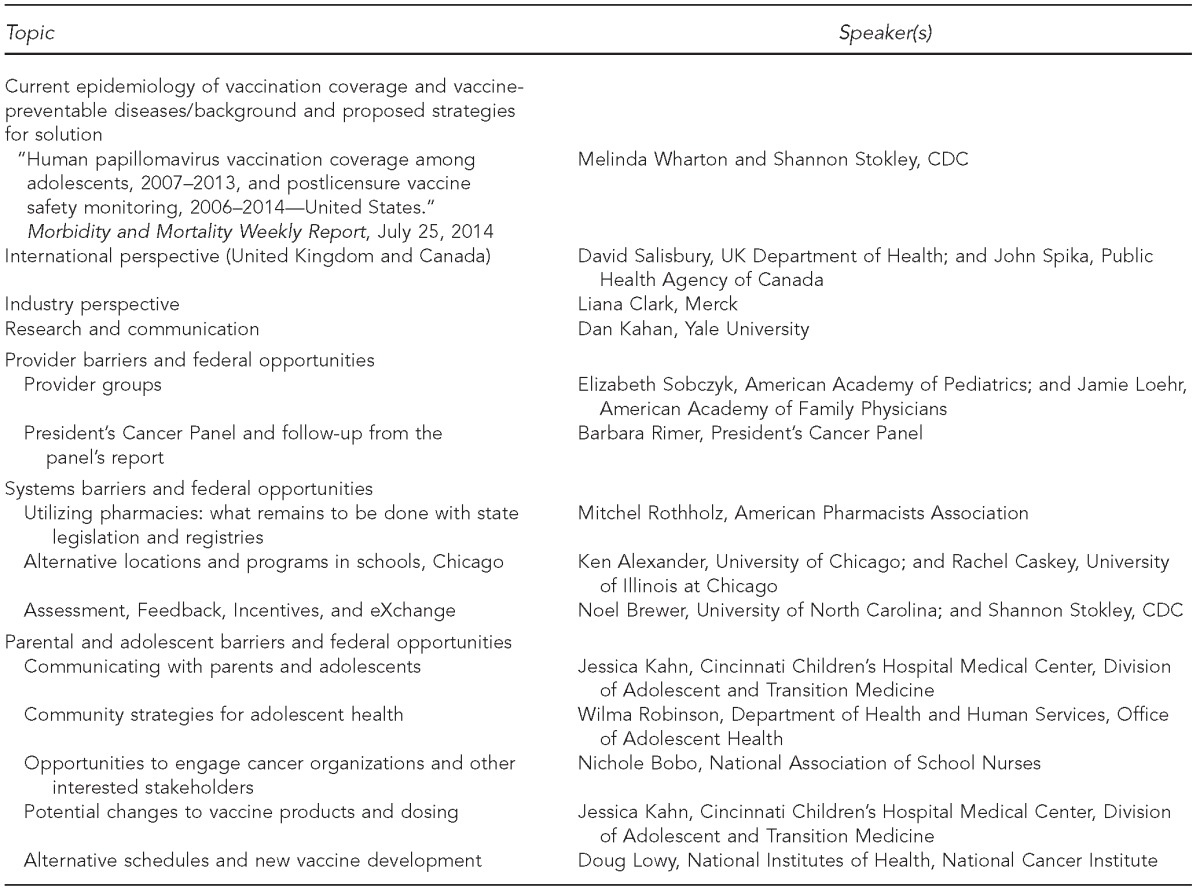

NVAC established the Human Papillomavirus Working Group (working group) in February 2013. In July 2013, the working group began hearing from external experts and stakeholders (Table 1) to inform its work and recommendations.

Table 1.

Invited speakers and topic presentations to the National Vaccine Advisory Committee Human Papillomavirus Working Group, teleconferences, 2013–2014

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

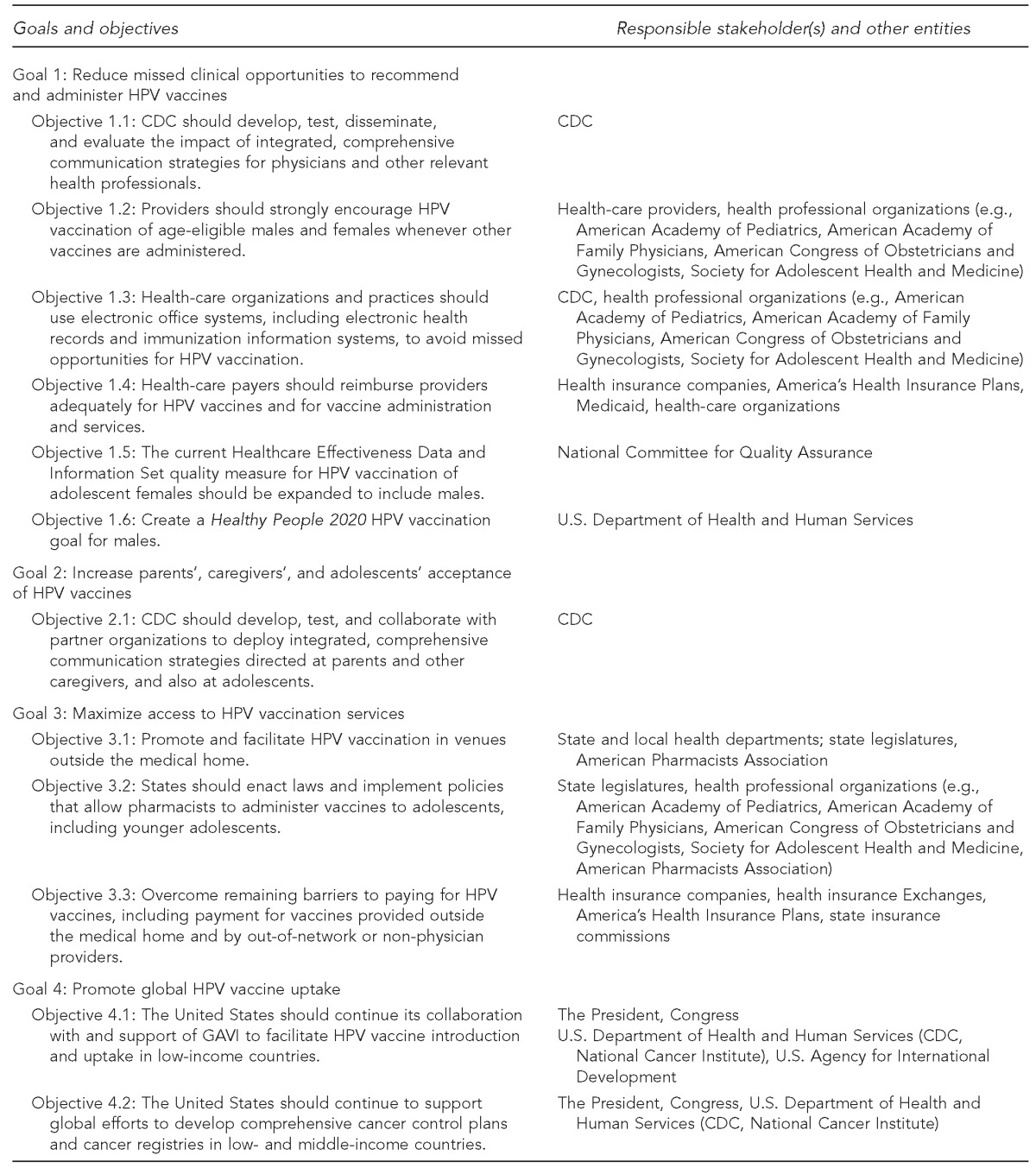

Concurrently, the President's Cancer Panel (PCP), a federal advisory committee of the National Institutes of Health's National Cancer Institute, was working on its annual report to the President. The PCP highlighted opportunities for primary prevention of cancer and focused on the use of HPV vaccines to prevent HPV-associated cancers. Its report, Accelerating HPV Vaccine Uptake: Urgency for Action to Prevent Cancer, released on February 10, 2014, provided recommendations on how to increase the use of HPV vaccination (Table 2).5

Table 2.

Goals, objectives, and responsible stakeholders outlined in the report, “Accelerating HPV vaccine uptake: urgency for action to prevent cancer,” President's Cancer Panel, 2014a

National Cancer Institute (US). Accelerating HPV vaccine uptake: urgency for action to prevent cancer. A report to the President of the United States from the President's Cancer Panel. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; 2014.

HPV = human papillomavirus

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The PCP presented its recommendations to the NVAC on February 11, 2014. Among other recommendations, the report recommended that NVAC “be given responsibility for monitoring the status of uptake and implementation of the recommendations.”5 The NVAC asked the working group to fully review the report and determine whether or not the NVAC should endorse and adopt the recommendations of the PCP and advise the ASH to do the same. On June 11, 2014, two recommendations were endorsed by the full NVAC.

SUPPORT FOR THE PCP REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 1. The ASH should endorse the PCP report, Accelerating HPV Vaccine Uptake: Urgency for Action to Prevent Cancer, and adopt the recommendations outlined therein.

Recommendation 2. As the PCP recommended, NVAC should monitor “the status of uptake and implementation of the recommendations.” This should be done by hearing an annual progress report from HPV vaccination stakeholders identified in the PCP report.

ADDITIONAL NVAC RECOMMENDATIONS

After endorsing Recommendations 1 and 2, the NVAC asked the working group to determine whether the PCP report completely addressed the charge given by the ASH, and, if not, whether the NVAC should consider making additional recommendations. The working group identified three additional recommendations, along with sub-recommendations, that complement those in the PCP report. These recommendations were developed after hearing from several external experts and incorporating the most recent data on strategies to increase HPV vaccination coverage. The ASH also asked the NVAC to identify strategies to overcome barriers to both initiation and completion of the HPV vaccine series.

The full set of recommendations, including Recommendations 3, 4, and 5, with sub-recommendations was approved on June 9, 2015.

Recommendation 3. The ASH should work with relevant agencies and stakeholders to develop evidence-based, effective, coordinated communication strategies to increase the strength and consistency of clinician recommendations for HPV vaccination to adolescents (both males and females) in the recommended age groups and to improve acceptance among parents/guardians, adolescents, and young adults.

Recommendation 3.1. Develop practical tools to increase clinicians' skills and confidence in promoting HPV vaccination as a routine adolescent vaccine and part of routine adolescent care. These communication tools should equip clinicians to emphasize HPV vaccine as a cancer prevention strategy, to increase clinicians' ability to respond to questions from parents/guardians and adolescents about HPV as a sexually transmitted infection, and to enable clinicians to effectively address parental hesitancy.

Recommendation 3.2. Develop evidence-based, culturally competent communication strategies for parents/guardians, adolescents, and young adults that address key beliefs driving decisions to vaccinate and address barriers to vaccination.

Recommendation 3.3. Promote collaboration among all stakeholders to coordinate communications and messaging that increase message consistency across professional organizations and their constituencies.

Recommendation 3.4. Utilize multiple methods for communication, including one-on-one counseling, public health messaging, social media, and decision support systems.

Recommendation 3.5. Promote science-based media coverage about HPV vaccination and appropriate response to media coverage that does not adequately reflect the science of HPV vaccines and HPV vaccination recommendations.

Both the PCP and the NVAC concluded that weak and inconsistent provider recommendations and low parental demand for HPV vaccination are two barriers to increasing coverage rates. National Immunization Survey data show that elimination of missed clinical opportunities to administer HPV vaccination would result in coverage rates of 80%–90% for the first dose. Missed clinical opportunities are defined as visits to a provider in which at least one other recommended adolescent vaccination was received.2 These data are concerning because they indicate that adolescents are visiting their providers and receiving routine vaccines but are not being vaccinated against HPV. These data also indicate a great opportunity for improving HPV vaccination coverage rates. Recommendation 3 builds upon several recommendations in the PCP report to develop strategies to support providers in effectively communicating the importance of HPV vaccination, to increase parental and adolescent demand for HPV vaccination, and to coordinate stakeholders to encourage consistent evidence-based messaging.

Providers most often cite financial concerns and parental attitudes and concerns as barriers to providing HPV vaccination to their patients.6 Discomfort with addressing questions about sexually transmitted infections and safety concerns are additional barriers for providers.7,8 Office strategies, such as reminder-recall systems and the distribution of information and educational materials from provider professional organizations, may help increase vaccination rates.

The National Immunization Survey reported that one-third of parents/guardians of girls and more than half of parents/guardians of boys did not receive a recommendation for HPV vaccination from their -clinicians.2 Although providers anticipate parental hesitancy about HPV vaccination, most parents/guardians report they would accept the vaccine for their adolescent children if their providers recommended it. Surveyed parents/guardians who have refused HPV vaccination for their children give a broad range of reasons, including the need for more information about HPV vaccination. They also cite other concerns as reasons for delaying or refusing HPV vaccination for their children: perceptions about safety, concerns about the vaccine's potential effect on sexual behavior, belief in a low risk of HPV infection, and a belief that their children are too young to need the vaccine.6

Taking these concerns into account the NVAC recommends that providers be supported with the information and tools they need to effectively and confidently recommend HPV vaccination for their patients and engage in any conversations that arise from that recommendation. The NVAC further recommends development of targeted communication strategies for parents/guardians and adolescents.

A broad community of stakeholders is dedicated to increasing HPV immunization. Accordingly, the NVAC suggests the need for improved collaboration among these organizations to increase the consistency and coordination of messages to promote HPV vaccination.

Recommendation 4. NVAC recommends the ASH should work with the relevant agencies and stakeholders to strengthen the immunization system in order to maximize access to and support of adolescent vaccinations, including HPV vaccines.

Recommendation 4.1. Addressing barriers to vaccination in venues outside the traditional primary care provider office, including pharmacies, schools, and public health departments. This may include immunization status assessment and administration of the appropriate doses toward completion of the HPV vaccination series.

Recommendation 4.1.1. Develop strategies to overcome barriers regarding reimbursement for vaccination administration and compensation of vaccine administrators and their staff.

Recommendation 4.1.2. Strengthen immunization information systems (IISs) to allow pharmacies, school-located programs, and public health clinics to view and query patient immunization records and submit records of immunizations administered to their state IIS, which ensures proper communication and record of immunization histories are available to the patient's primary care provider, vaccination administrator, and the state public health system.

Recommendation 4.1.3. Encourage collaboration and sharing of best practices for successful vaccination programs at pharmacies, schools, and public health clinics.

Recommendation 4.2. Working with relevant agencies and stakeholders to increase the widespread use of quality improvement strategies, such as Assessment, Feedback, Incentives, and eXchange (AFIX) visits, to support and evaluate HPV immunization practices within all vaccination venues.

Recommendation 4.3. Encouraging widespread adoption of state-centralized reminder recall for adolescent vaccines and reporting of vaccinations into existing immunization information systems and electronic health records.

In 2008, the NVAC issued a report and paper on adolescent vaccinations that outlined strategies to create a system for adolescent immunization. This report highlighted the fact that fewer adolescents, compared with other pediatric groups, access the medical system for preventive care, either in public or private delivery venues, and that, when they do, it is most often for acute care. Therefore, ensuring that adolescents have access to vaccines and other measures of preventive care is a unique challenge. The topics addressed in the 2008 report that had unique applications to adolescent immunization were: alternative venues for vaccine administration, financing, consent for immunizations, communication, surveillance, and the potential for school entry requirements.9 Much progress has been made toward addressing these topics. Notably, the Affordable Care Act ensures reimbursement for all ACIP-recommended adolescent vaccinations at in-network providers. In addition, national coverage targets have been established along with systems of surveillance of adolescent vaccine coverage, disease burden, and vaccine safety. However, some of the same challenges identified still exist. In Recommendation 4, the NVAC once again turns its attention to IISs and recommends ways to continue to increase access to immunization services for adolescents. The strategies outlined in Recommendation 4 are especially important to addressing barriers related to completing the three-dose HPV vaccine series.

As identified in the 2008 report and also highlighted in the PCP report, using appropriate complementary settings for adolescent vaccination is an important strategy for reaching adolescents and ensuring their access to vaccination services. The physician office or medical home is an essential venue for health-care delivery, including immunizations, and does provide vaccines to a large portion of adolescents. However, given the pattern of health-care utilization among adolescents, this venue alone may not adequately provide access for all adolescents, especially for HPV vaccination, which requires follow-up visits to complete the three-dose series. The NVAC believes other venues must be considered to reach national goals for HPV immunization. Toward this goal, the NVAC recommends addressing barriers to vaccination at pharmacies, schools, and public health clinics.

Although many physician professional organizations prefer that all vaccinations be given within the medical home,10–13 recognition is growing that new strategies may be required for HPV vaccination, given the unique challenge of the three-dose series along with the low rates of vaccination coverage. In an unpublished letter to the NVAC, the American Academy of Family Physicians stated that it would accept the second and third HPV vaccine doses being administered outside the medical home as long as those sites were required to report all doses given to the medical home and state registry.

Despite growing support for alternative venues for vaccination, many challenges prevent scaling them up nationally. The PCP concluded that pharmacies were the most promising alternative to medical home vaccination now, and it made recommendations to overcome barriers to pharmacy-based vaccination. The NVAC supports those recommendations.5 In addition, the NVAC concluded that, although the challenges to school-located vaccination programs may be great, the potential of these programs to increase access and ultimately increase vaccination coverage rates was worth continued effort and attention.

One of the primary barriers to vaccination programs at pharmacies, schools, and public health clinics is reimbursement and compensation. Although the Affordable Care Act requires first-dollar coverage for ACIP-recommended vaccines,14 including HPV vaccine administered at in-network providers, alternative settings do not always qualify as in-network providers and, therefore, are ineligible for reimbursement for vaccines administered. Therefore, creating in-network status for alternative vaccination sites will be required to make these programs feasible.15 Even with in-network status, billing insurance is a challenge in school settings because students are covered by public insurers or an array of private insurers. Furthermore, compensation for staff time and administration costs is often not adequately covered by insurance. The NVAC recommends the development of strategies to overcome these barriers.

A second challenge to alternative settings is their ability to adequately document vaccine doses to state IISs and to the adolescents' primary care providers.15,16 Providers in alternative settings often do not have access to state IIS or medical records. In addition, standardized methods do not exist for alternative settings to submit information on vaccines administered to their state registries or report back to primary care providers. Therefore, the NVAC recommends addressing these issues of access to IIS and medical records to ensure proper documentation and facilitate partnerships with primary care providers.

The NVAC discussed other challenges unique to school-located vaccination programs. For example, the principal of each school ultimately decides whether or not to allow vaccination programs at their schools. Acquiring consent forms from students and their parents/guardians is a substantial challenge. To overcome these barriers, the NVAC recommends collaboration and sharing of information among pharmacies, school-located programs, and public health clinics. These locations have found ways to overcome the aforementioned barriers in addition to other venue-specific challenges. Ensuring that their best practices and methods for success are shared widely will help expand these programs to additional locations and expand access to vaccination services for adolescents; certain alternative methods may work better in some settings than in others.

National Vaccine Advisory Committee.

Chair

Walter A. Orenstein, MD, Emory University, Atlanta, GA

Designated Federal Official

Bruce G. Gellin, MD, MPH, National Vaccine Program Office, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Public Members

Richard H. Beigi, MD, MSc, Magee-Womens Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA

Sarah Despres, JD, Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington, DC

Ruth Lynfield, MD, Minnesota Department of Health, St. Paul, MN

Yvonne Maldonado, MD, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA

Charles Mouton, MD, MS, Meharry Medical College, Nashville, TN

Wayne Rawlins, MD, MBA, Aetna, Hartford, CT

Mitchel C. Rothholz, RPh, MBA, American Pharmacists Association, Washington, DC

Nathaniel Smith, MD, MPH, Arkansas Department of Health, Little Rock, AR

Kimberly Thompson, ScD, University of Central Florida, College of Medicine, Orlando, FL

Catherine Torres, MD, Former New Mexico Secretary of Health, Las Cruces, NM

Kasisomayajula Viswanath, PhD, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA

Representative Member

Philip Hosbach, Sanofi Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA

National Vaccine Advisory Committee (Nvac) Human Papillomavirus (Hpv) Working Group

HPV Working Group Chairs

Sarah Despres, JD, Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington, DC

Wayne Rawlins, MD, MBA, Aetna, Hartford, CT

NVAC Chairman

Walter A. Orenstein, MD, Emory University, Atlanta, GA

NVAC Members

Richard H. Beigi, MD, MSc, Magee-Womens Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA

Philip Hosbach, Sanofi Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA

Mitchel C. Rothholz, RPh, MBA, American Pharmacists Association, Washington, DC

Kasisomayajula Viswanath, PhD, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA

NVAC Liaison Representatives

Nichole Bobo, MSN, RN, National Association of School Nurses, Silver Spring, MD

Noel T. Brewer, PhD, President's Cancer Panel, Bethesda, MD

Linda Eckert, MD, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Washington, DC

Paul Etkind, DrPH, National Association of County and City Health Officials, Washington, DC

Jessica A. Kahn, MD, MPH, Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine, Oakbrook Terrace, IL

Jamie Loehr, MD, American Academy of Family Physicians, Ithaca, NY

Kim Martin, Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, Arlington, VA

Julie Morita, MD, Chicago Department of Public Health, Chicago, IL

David Salisbury, CB, UK Department of Health, London

Debbie Saslow, PhD, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA

Litjen (LJ) Tan, PhD, MS, Immunization Action Coalition, St. Paul, MN

James C. Turner, MD, American College Health Association, Hanover, MD

Rodney E. Willoughby, Jr., MD, American Academy of Pediatrics, Leawood, KS

NVAC Ex Officio Members

Valerie Borden, MPA, Office on Women's Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Robert Croyle, PhD, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD

Carolyn D. Deal, PhD, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD

Rebecca Gold, JD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA

Mary Beth E. Hance, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, Baltimore, MD

Maureen A. Hess, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD

Nancy C. Lee, MD, Office on Women's Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Douglas Lowy, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD

Shannon Stokley, MPH, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA

Melinda Wharton, MD, MPH, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Vaccine Program Office Staff and Technical Advisors

Sharon Bergquist, PhD, National Vaccine Program Office, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Karin Bok, PhD, National Vaccine Program Office, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Bruce G. Gellin, MD, MPH, National Vaccine Program Office, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Katy Seib, MPH, Emory University, Atlanta, GA

Maggie Zettle, PharmD, National Vaccine Program Office, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Finally, the NVAC recommends widespread use of quality improvement strategies and state or regionally centralized reminder-recall systems. These programs have been shown to successfully increase vaccination coverage rates and, therefore, should be adopted more broadly.17

Recommendation 5. The ASH should encourage the review or development of available data that could lead to a simplified HPV vaccination schedule. In addition to a review that could impact existing vaccines, manufacturers of HPV vaccines in development should also consider opportunities to support the simplest HPV immunization schedule while maintaining vaccine effectiveness, safety, and long-term protection.

A growing body of evidence suggests that equivalent protection from HPV disease may be possible with fewer vaccine doses.18–21 A simplification of the schedule—by reducing the number of doses required or vaccinating at alternative ages—would help to relieve some of the difficulty in series completion and reduce cost. Immunological noninferiority has been shown for two doses in those aged 9–13 years compared with three doses in those aged 15–25 years.18,20,21 In addition, early data from a trial in Costa Rica for the HPV2 vaccine also suggest equivalent efficacy of one and two doses.19 These data have led the European Medical Agency and the World Health Organization to recommend a two-dose schedule, and many countries have also adopted a two-dose schedule. Although the data look promising, further post-licensure data are needed to confirm that fewer doses are equally effective at preventing persistent HPV infection and providing long-lasting protection.

Antibody levels to HPV vaccine have been demonstrated for up to five years after vaccination.22,23 Further research is planned to determine the duration of protection and antibody levels through at least 14 years of age after series completion. Accordingly, the NVAC recommends that the ASH encourage continued review of available data or support for additional data that could determine whether or not fewer doses are equivalent in both effectiveness and safety to the current three-dose schedule, and whether or not alternative ages of administration are a viable option based on long-term protection. The NVAC recognizes that changes to the recommended immunization schedule are the responsibility of ACIP and that ACIP continues to review these data.

Given the potential changes outlined previously, the NVAC had lengthy discussions on how best to communicate a change in vaccine recommendation or dose schedule, or both. The NVAC cautions that attention should be paid to ensuring that the public and vaccine providers understand the reasons for and the data supporting any changes made. In addition, the NVAC stressed that providers should continue to recommend and provide HPV vaccination during this period of potential transition.

CONCLUSION

With more than 25,000 cases of HPV-associated cancers diagnosed annually in the United States, routine administration of HPV vaccines is imperative. Greater HPV vaccination of 11- and 12-year-olds could reduce the rates of persistent HPV infection, which is currently the leading cause of cervical, anal, oropharyngeal, vaginal, vulvar, and penile cancers.1 The current low rates of vaccination highlight the many challenges to both initiating the first HPV vaccine dose and completing the three-dose series. Adhering to the recommendations of the NVAC and the PCP can ease these challenges. The NVAC will review data on HPV vaccination coverage at least annually to assess the impact of both the PCP and NVAC recommendations, to evaluate the strategies that are being developed, to respond to them, and, ultimately, to assess impact on HPV vaccination coverage.

Footnotes

The views represented in this report are those of the NVAC. The positions expressed and recommendations made in this report do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. government, or the individuals who served as authors of, or otherwise contributed to, this report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, Noone AM, Markowitz LE, Kohler B, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:175–201. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stokley S, Jeyarajah J, Yankey D, Cano M, Gee J, Roark J, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescents, 2007–2013, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006–2014—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(29):620–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:187–93. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318286bb53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Lowy DR. HPV prophylactic vaccines and the potential prevention of noncervical cancers in both men and women. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):3036–46. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute (US) Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; 2014. Accelerating HPV vaccine uptake: urgency for action to prevent cancer. a report to the President of the United States from the President's Cancer Panel. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:76–82. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vadaparampil ST, Malo TL, Kahn JA, Salmon DA, Lee JH, Quinn GP, et al. Physicians' human papillomavirus vaccine recommendations, 2009 and 2011. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:80–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahn JA, Cooper HP, Vadaparampil ST, Pence BC, Weinberg AD, LoCoco SJ, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine recommendations and agreement with mandated human papillomavirus vaccination for 11- to-12-year-old girls: a statewide survey of Texas physicians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2325–32. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Vaccine Advisory Committee. The promise and challenge of adolescent immunization. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:152–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Pediatrics. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1 Pt 1):184–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Family Physicians. Immunizations [cited 2015 Dec 3] Available from: http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/immunizations.html.

- 12.American Academy of Family Physicians. Letter to Suzanne Johnson-DeLeon, Health Education and Information Specialist, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 Mar 4 [cited 2015 Dec 3] Available from: http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/advocacy/prevention/vaccines/LT-CDC-PediatricImmunization-030415.pdf.

- 13.Szilagyi PG, Rand CM, McLaurin J, Tan L, Britto M, Francis A, et al. Delivering adolescent vaccinations in the medical home: a new era? Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 1):S15–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1115C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 et seq. (2010)

- 15.Shah PD, Gilkey MB, Pepper JK, Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT. Promising alternative settings for HPV vaccination of US adolescents. 2014 [cited 2014 Nov 7] Available from: http://informahealthcare.com.ezproxyhhs.nihlibrary.nih.gov/doi/full/10.1586/14760584.2013.871204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Lindley MC, Boyer-Chu L, Fishbein DB, Kolasa M, Middleman AB, Wilson T, et al. The role of schools in strengthening delivery of new adolescent vaccinations. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 1):S46–54. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1115F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Recommendations regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 Suppl):92–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobson SRM, McNeil S, Dionne M, Dawar M, Ogilvie G, Krajden M, et al. Immunogenicity of 2 doses of HPV vaccine in younger adolescents vs 3 doses in young women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1793–802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreimer AR, Rodriguez AC, Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Porras C, Schiffman, et al. Proof-of-principle evaluation of the efficacy of fewer than three doses of a bivalent HPV16/18 vaccine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1444–51. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romanowski B, Schwarz TF, Ferguson LM, Ferguson M, Peters K, Dionne M, et al. Immune response to the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine administered as a 2-dose or 3-dose schedule up to 4 years after vaccination: results from a randomized study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:1155–65. doi: 10.4161/hv.28022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazcano-Ponce E, Stanley M, Muñoz N, Torres L, Cruz-Valdez A, Salmerón J, et al. Overcoming barriers to HPV vaccination: non-inferiority of antibody response to human papillomavirus 16/18 vaccine in adolescents vaccinated with a two-dose vs. a three-dose schedule at 21 months. Vaccine. 2014;32:725–32. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler CM, Moscicki AB, Romanowski B, Roteli-Martins CM, et al. Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1247–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villa LL, Costa RLR, Petta CA, Andrade RP, Paavonen J, Iversen OE, et al. High sustained efficacy of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus types 6/11/16/18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine through 5 years of follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1459–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]