Abstract

Objective

The Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning (ECHPP) project was a demonstration project implemented by 12 U.S. health departments (2010–2013) to enhance HIV program planning in cities with high AIDS prevalence, in support of National HIV/AIDS Strategy goals. Grantees were required to improve their planning and implementation of HIV prevention and care programs to increase their impact on local HIV epidemics. A multilevel evaluation using multiple data sources, spanning multiple years (2008–2015), will be conducted to assess the effect of ECHPP on client outcomes (e.g., HIV risk behaviors) and impact indicators (e.g., new HIV diagnoses).

Methods

We designed an evaluation approach that includes a broad assessment of program planning and implementation, a detailed examination of HIV prevention and care activities across funding sources, and an analysis of environmental and contextual factors that may affect services. A data triangulation approach was incorporated to integrate findings across all indicators and data sources to determine the extent to which ECHPP contributed to trends in indicators.

Results

To date, data have been collected for 2008–2009 (pre-ECHPP implementation) and 2010–2013 (ECHPP period). Initial analysis of process data indicate the ECHPP grantees increased their provision of HIV testing, condom distribution, and partner services programs and expanded their delivery of prevention programs for people diagnosed with HIV.

Conclusion

The ECHPP evaluation (2008–2015) will assess whether ECHPP programmatic activities in 12 areas with high AIDS prevalence contributed to changes in client outcomes, and whether these changes were associated with changes in longer-term, community-level impact.

In 2010, the White House released the National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS), a five-year plan that detailed principles, priorities, and actions to guide the national response to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic.1 NHAS included four main goals: reduce new HIV infections, increase access to care and optimal health outcomes for people living with HIV infection (PLWH), reduce HIV-related health disparities, and achieve a more coordinated response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In support of this national strategy, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted the Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning (ECHPP) project from September 30, 2010, to September 29, 2013.2,3 Through ECHPP, health departments in the 12 U.S. metropolitan statistical areas with the highest prevalence of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) were required to conduct a situational analysis of all their HIV prevention and care activities (across all sources of HIV funding). Based on this analysis, the health departments were required to develop a set of goals and strategies that would increase the impact of their HIV programs on the local epidemic and increase the likelihood they would meet NHAS goals.

The ECHPP project was unique in that it required CDC's Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention to evaluate the collective implementation of numerous HIV prevention and care interventions across multiple sites. Typically, a program evaluation focuses on an assessment of a single intervention or program and whether or not intended client outcomes were achieved, comparing outcomes of the intervention arm with the outcomes of a planned control or comparison arm, in which a similar population did not receive the intervention. Funded with non-research (i.e., program) funds, the ECHPP project did not have a research design that used random assignment or planned comparison groups. Instead, the ECHPP project used a new programmatic approach that charged health departments with making local programmatic changes to maximize the impact of their HIV programs, considering all sources of HIV funding (CDC and other federal, state, local, and private funding streams). Additionally, the ECHPP evaluation was designed to use data from existing data sources only, avoiding the need to conduct new, costly, and time-consuming data collection activities. Taking these factors into consideration, to assess the overall success of the ECHPP project, the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention developed an evaluation approach that would accommodate 12 unique program models implemented in 12 unique geographic areas with 12 unique local epidemics. This article describes the overall evaluation approach and specific evaluation activities; some have been completed, and others are in progress.

The overall ECHPP evaluation goals are ultimately to assess whether or not ECHPP programmatic activities in 12 areas with a high prevalence of AIDS contributed to changes in client outcomes (e.g., client-reported HIV risk behaviors and access to service) and whether or not the changes in client outcomes were associated with changes in longer-term measures of impact (e.g., community-level trends in HIV diagnoses and prevalence). Once completed, this evaluation will provide a better understanding of HIV-related activities supported by health departments in high-prevalence areas and how health departments leveraged local prevention and care resources to increase local impact. Additionally, the evaluation will provide an opportunity for federal agencies to identify strategies that increase the coordination, collaboration, and integration of HIV-related services and the standardization and streamlining of data collection both within and across agencies.4–6

METHODS

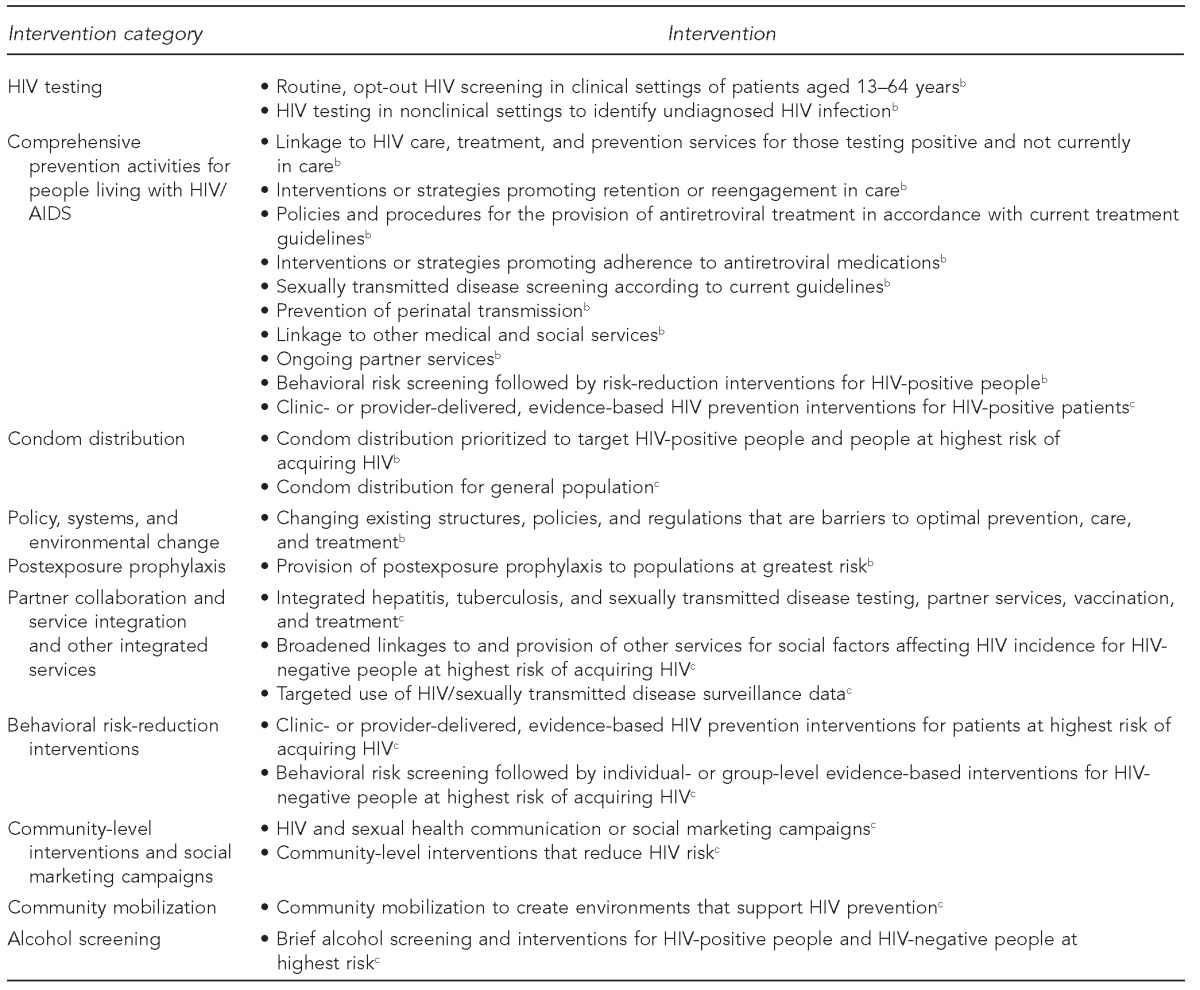

Each health department was required to develop an enhanced comprehensive HIV program plan to describe how it would improve its HIV prevention and care services using a combination of interventions, intervention targets, and intervention scales to optimize impact on NHAS goals.3 Program plans focused on priority populations (black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, injecting drug users, high-risk heterosexuals, men who have sex with men, and PLWH) consistent with the needs of the local epidemic. CDC provided a list of 24 required or recommended interventions (Table 1), many of which were already being implemented at some level in these sites. Innovative local initiatives, if approved by CDC, could also be included in a health department's plan.

Table 1.

Required and recommended interventions, by category—Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning (ECHPP) project sites,a 2010–2013

The 12 ECHPP sites were Atlanta, Georgia; Baltimore, Maryland; Chicago, Illinois; Dallas, Texas; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles, California; Miami, Florida; New York, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; San Francisco, California; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Washington, D.C.

bRequired intervention

cRecommended intervention

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Health department grantees received approximately $43 million from CDC under the ECHPP cooperative agreements during 2010–2013, which represented a relatively small proportion of their overall HIV budget (approximately 7% of their CDC HIV prevention funds). The health departments were expected to use the ECHPP cooperative agreement funds primarily for planning and secondarily for some initial implementation; however, most activities during 2010–2013 were supported by other health department funds (i.e., other CDC funds, non-CDC federal funds, state funds, and local funds). The 12 ECHPP sites were Atlanta, Georgia; Baltimore, Maryland; Chicago, Illinois; Dallas, Texas; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles, California; Miami, Florida; New York, New York; Philadelphia, -Pennsylvania; San Francisco, California; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Washington, D.C.

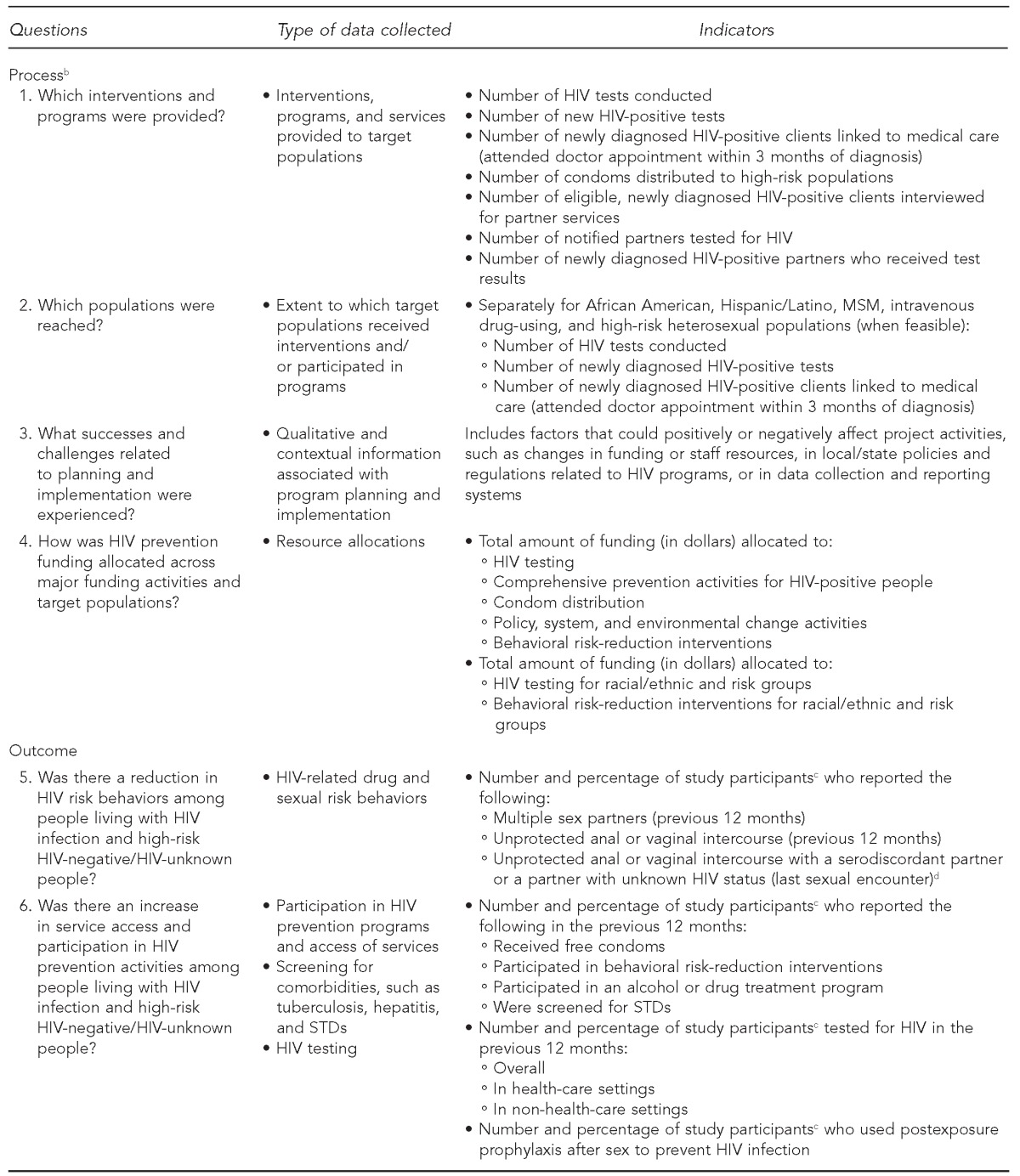

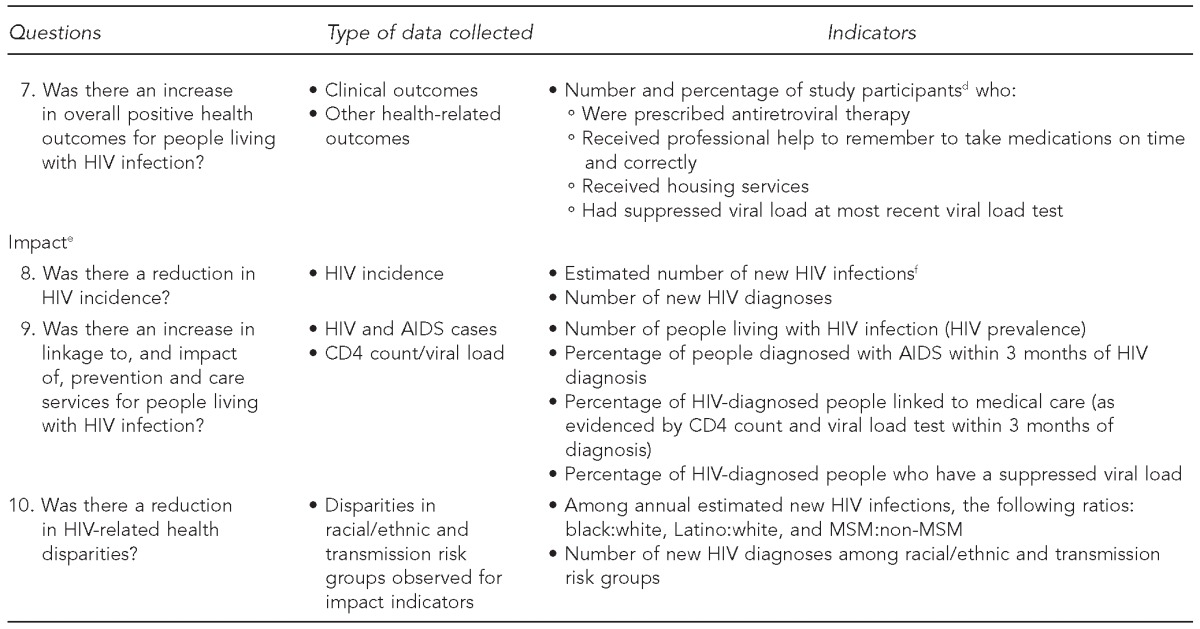

Development of the evaluation framework

CDC's evaluation approach for ECHPP comprises several components: (1) a broad assessment of program planning and implementation of HIV prevention and care activities across multiple funding sources, (2) a detailed examination of core HIV prevention activities across multiple years, and (3) an analysis of local environmental and contextual factors that can affect services. To date, data have been collected for 2008–2009 (two years prior to ECHPP implementation) and 2010–2013 (during ECHPP implementation). Data for the two years after ECHPP implementation (2014–2015) will be obtained when available. This data collection will allow us to describe trends and changes across an eight-year period in these 12 sites. Data analysis will extend beyond 2015 by several years because of time lags in data availability. The evaluation consists of process questions, outcome questions, and impact questions (Table 2), along with various types of data collected and numerous indicators. The development of the evaluation framework was led by the ECHPP evaluation team at CDC with input from stakeholders, subject matter experts from the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, and the 12 ECHPP health department grantees.

Table 2.

Process, outcome, and impact questions, type of data collected, and indicators for evaluation of the Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning (ECHPP) project sites,a 2010–2013

The 12 ECHPP sites were Atlanta, Georgia; Baltimore, Maryland; Chicago, Illinois; Dallas, Texas; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles, California; Miami, Florida; New York, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; San Francisco, California; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Washington, D.C.

bData reported by health department grantees to the National HIV Prevention Program Monitoring and Evaluation System (http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/surveillance/index.html) and through the ECHPP progress reports. Data represent services delivered to high-risk, HIV-negative/HIV-unknown, and HIV-diagnosed people.

cData represent self-reported behaviors, access of services, and participation in HIV programs among high-risk, HIV-negative/HIV-unknown people in the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System (http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/surveillance/systems/index.html).

dData represent self-reported behaviors, access of services, and participation in HIV programs among HIV-diagnosed participants in the Medical Monitoring Project (http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/surveillance/systems/index.html).

eData represent HIV case and laboratory data reported by health department grantees to the National HIV Surveillance System (http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/surveillance/index.html).

fHIV incidence estimation methods have been described by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_hssr_vol_17_no_4.pdf).

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

MSM = men who have sex with men

STD = sexually transmitted disease

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Data sources

Preexisting data sources, both internal (e.g., National HIV Surveillance System) and external (e.g., National STD Surveillance System) to CDC were reviewed and selected on the basis of the availability of indicators that could be used to answer the evaluation questions. The following general approach was used:

Use data from existing data sources when possible.

Identify indicators that are amenable to standardization across data sources.

Collect process data associated with program and intervention delivery that can be plausibly linked to client outcomes.

Collect client outcome data that can be plausibly linked to impact data.

Identify non-CDC data sources that may contribute to overall findings.

Process data.

We obtained process data (associated with program and intervention delivery) from several data sources. Grantees submitted process data through routine progress reports on HIV-related activities funded from all sources. Funding sources included CDC, the Health Resources and Services Administration–HIV/AIDS Bureau, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and state, local, and private sources. In these progress reports, grantees described their planning process and implementation for each intervention in their ECHPP plan, including successes and challenges. Grantees also submitted data on their total annual budget allocations for HIV prevention from all funding sources for the following program categories: HIV testing, comprehensive prevention services for PLWH, condom distribution, and behavioral risk-reduction interventions. When the data were available, grantees also provided data on allocations directed toward target populations. Expenditure data were not available. We also obtained CDC-funded testing data submitted by grantees to the National HIV Prevention Program Monitoring and Evaluation (NHM&E) System.7

Additionally, we will explore environmental and contextual factors relevant to local HIV epidemics, but not directly related to ECHPP, in participating ECHPP sites. Such factors include, for example, a local HIV-related clinical trial conducted during the study period, as well as STD prevalence8 and poverty rate,9 which are associated with HIV risk and related outcomes and have the potential to affect ECHPP findings. Funding levels of health department programs are also considered to be a contextual factor, because a decrease in resources for services in general could adversely affect client-level outcomes and community impact.

Outcome data.

Outcome data for self-reported HIV risk behaviors and screening for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) were obtained from the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System (NHBS) (i.e., self-report data collected from high-risk, HIV-negative individuals and individuals who do not know their HIV status)10 and the Medical Monitoring Project (i.e., data collected from PLWH who are receiving HIV care).11 Data on risk behaviors included the percentage of participants who received free condoms, participated in a behavioral risk-reduction intervention or an alcohol or drug treatment program, or were screened for STDs. We obtained additional outcome data related to the HIV care continuum4,12,13 from the Medical Monitoring Project. These data included (1) self-reported survey data on the percentage of participants who received professional help with medication adherence and the percentage who received housing services and (2) medical chart abstraction data on the percentage of participants who were prescribed antiretroviral therapy and the percentage who had a suppressed viral load at the most recent viral load test in the previous 12 months. We also collected data on the percentage of NHBS participants who tested for HIV and the percentage who used antiretroviral therapy (postexposure prophylaxis) after sex because they believed it would prevent HIV infection. All outcome data represent adults aged 18 years or older, stratified by race/ethnicity and transmission risk group in the previous 12-month period, except for one NHBS indicator: the percentage of participants who reported having unprotected sex with a serodiscordant partner or a partner whose HIV status was unknown at last sexual encounter.

Impact data.

Impact data obtained from the National HIV Surveillance System14 include the following indicators: estimated number of diagnosed and undiagnosed new HIV infections (incidence), number of new HIV diagnoses, number of people living with HIV infection (prevalence), percentage of people diagnosed with AIDS within three months of HIV diagnosis, percentage of HIV-positive people linked to medical care (as evidenced by CD4 count and viral load test within three months of diagnosis), and percentage of HIV-diagnosed people who have a suppressed viral load. All National HIV Surveillance System data represent people aged 13 years or older, stratified by race/ethnicity and transmission risk group.

Data analysis

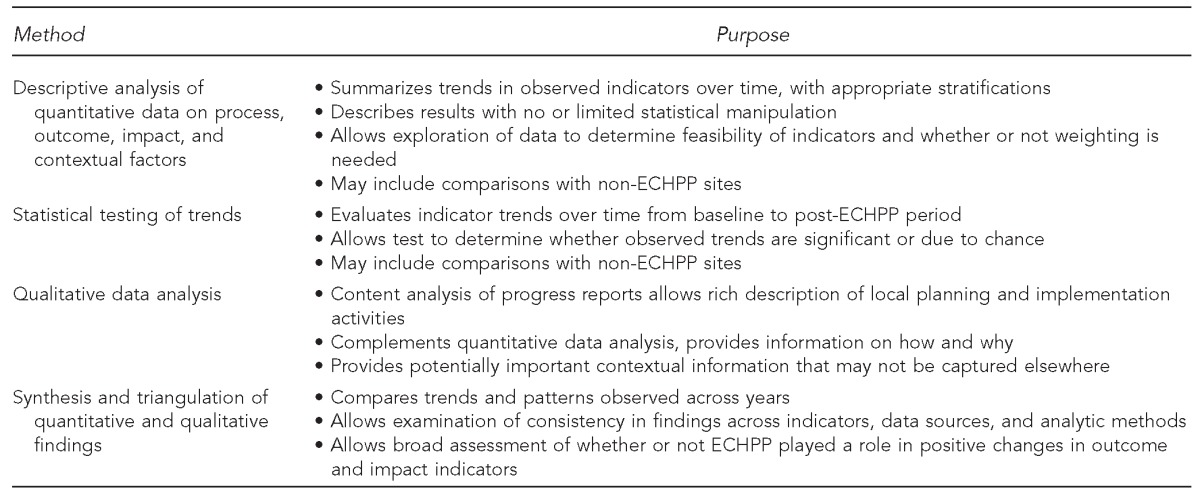

Table 3 summarizes proposed analytic methods. When evaluation data for all eight years (2008–2015) are available, the first step in data analysis will be to produce descriptive tables and graphs of the quantitative data on process, outcome, impact, and contextual factors by year. Descriptive statistics will summarize annual changes in programs delivered and target populations reached; outcomes for risk behaviors and service access among target populations; and estimated HIV incidence, HIV diagnoses, linkage to HIV medical care, and viral suppression among target populations. Because summary measures may conceal underlying trends and associations, data will also be explored by ECHPP site, transmission risk, race/ethnicity, and HIV status to assess, for example, whether a single site or target population accounts for a large proportion of the observations. Statistical testing of trends will be conducted to determine whether or not changes in indicators during the eight-year period are significant.

Table 3.

Data analytic methods and purposes for evaluation of the Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning (ECHPP) project sites,a 2010–2013

The 12 ECHPP sites were Atlanta, Georgia; Baltimore, Maryland; Chicago, Illinois; Dallas, Texas; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles, California; Miami, Florida; New York, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; San Francisco, California; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Washington, D.C.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

For the qualitative analysis, we plan to use thematic coding methods to identify themes of cross-jurisdictional planning and implementation reported through the ECHPP progress reports.15 The qualitative findings will provide a comprehensive picture of how these health departments shifted their programmatic activities in response to NHAS, successes and barriers experienced, and a description of strategies used to overcome barriers. These results will also help us interpret trends and patterns observed in the quantitative data analysis. To date, thematic coding has been completed for three of the 14 required interventions: linkage to HIV care, treatment, and prevention services for PLWH who are not in care; interventions or strategies promoting retention or reengagement in care; and interventions or strategies promoting adherence to antiretroviral treatment.16

Data triangulation will be used to review and synthesize quantitative and qualitative findings to determine whether or not ECHPP can be linked to significant changes in indicators. This approach, described by Rutherford and colleagues,17 integrates data from multiple existing data sources to answer broad public health questions, assess local and national trends in HIV indicators, and guide program policy. We will synthesize data across all indicators and data sources, incorporating non-ECHPP–related contextual data to inform trends and rule out alternate interpretations. For example, an analysis of outcome and impact indicators comparing ECHPP sites and non-ECHPP sites could provide additional evidence on whether or not ECHPP activities contributed to improving overall trends. Comparison cities will be selected according to disease burden (e.g., overall HIV/AIDS prevalence in the metropolitan statistical area, among black/African American people, and among Hispanic/Latino people), population demographics (e.g., number of black/African American and Hispanic/Latino people living in the metropolitan statistical area), and data availability. Analyses involving comparison cities will focus on required interventions and on the most important indicators (e.g., indicators related to HIV continuum of care for PLWH) to prevent the evaluation from becoming unwieldy and to ensure the findings are not so complex that they are uninterpretable.

A complete analysis of all process, outcome, and impact data cannot be conducted until the 2014–2015 post-ECHPP data are available.

RESULTS

Initial analyses of the process data indicate that the 12 health departments significantly increased their funding allocations for HIV testing and condom distribution activities and significantly increased their provision of important HIV prevention programs during the project period (2011–2013), in alignment with NHAS goals. Details on initial results are provided elsewhere in this issue.16 Specifically, ECHPP grantees significantly increased the number of African American people tested for HIV, the number of Hispanic/Latino people tested for HIV, the number of people newly diagnosed with HIV who were interviewed for partner services, the number of named partners who were tested for HIV, the number of newly diagnosed HIV-positive partners who received their test results, and the number of condoms distributed. Thematic coding of the ECHPP progress reports to date has identified common themes in implementing linkage to HIV medical care (e.g., 11 of 12 grantees reported piloting new, innovative linkage program models) and in improving treatment adherence among PLWH (e.g., nine of 12 grantees reported improving capacity of providers, case managers, and care coordination staff). However, the strategies grantees used to improve their linkage to care, retention and reengagement in care, and treatment adherence programs for PLWH varied widely.16 Details on how the grantees scaled up their HIV programs during ECHPP are provided elsewhere in this issue.3

LESSONS LEARNED

A number of challenges are expected with the evaluation approach described in this report, such as determining how cross-city differences in planning and implementation contribute to overall trends. Also, the planning and programmatic changes that took place in these cities because of ECHPP might not produce outcomes until years after the project ends. For example, ECHPP outcome and impact data for 2015 will not be available until 2017 or 2018. Establishing new relationships and methods for service delivery and data sharing is important for the long-term success of these programs, but it can be time-consuming and may affect the evaluation timeline. Although progress was made in data standardization and harmonization across federal agencies since NHAS was announced, much of this progress was concurrent with ECHPP and may not directly benefit our analyses. Although time-consuming, collaboration with other agencies will help to minimize the need for new data collections, reduce the burden on grantees of reporting data, and connect staff members across agencies who are knowledgeable about HIV-related data systems and variables.

We anticipate additional challenges during data analysis. In all participating cities, implementation was affected by changes in funding levels, programmatic priorities, data reporting systems, health-care legislation, and environmental factors, such as poverty and health insurance coverage rates. The evaluation must describe these changes and how they contributed to overall findings where feasible. At best, the evaluation team will be able to establish plausible linkages among programs, client outcomes, and community-level impact, but it will not be possible to infer that ECHPP caused the changes. Lastly, some data sources have special challenges. NHBS and Medical Monitoring Project survey questions (sources of ECHPP outcome data) were not developed specifically for ECHPP. Thus, extrapolations to broader risk groups must be made with care.

The ECHPP evaluation strategy represents the first time that CDC's Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention will use a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation approach to (1) assess whether or not HIV programs funded by various CDC and non-CDC sources were implemented collectively as intended by health departments, (2) determine whether or not changes in important client outcomes and longer-term community-level impact measures were observed among priority populations in high AIDS prevalence cities where health departments enhanced their program planning efforts, and (3) monitor progress toward NHAS goals in communities hardest hit by HIV. These findings will help CDC assess whether or not NHAS and other national goals were met in 2015, locally and nationally, given that these cities collectively are home to a large portion of the PLWH population. Additionally, programmatic information reported through the ECHPP progress reports will provide details about the challenges these jurisdictions faced in the midst of significant shifts in programmatic priorities, financial support, data utilization and reporting, and coordination across local, state, and federal groups.

Footnotes

The authors acknowledge the Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning (ECHPP) Project Steering Committee, the ECHPP Evaluation Team, and the health department grantees for their input on the evaluation design and methods.

Portions of this article were presented at the 2012 International AIDS Conference, Washington, DC, July 25, 2012. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.The White House (US), Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy. 2010 [cited 2015 Jul 6] Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Enhanced comprehensive HIV prevention planning and implementation for metropolitan statistical areas most affected by HIV/AIDS [cited 2015 Aug 2] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/demonstration/echpp.

- 3.Flores SA, Purcell DW, Fisher HH, Belcher L, Carey JW, Courtenay-Quirk C, et al. Shifting resources and focus to meet the goals of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy: the Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning project, 2010–2013. Public Health Rep. 2016;131:52–8. doi: 10.1177/003335491613100111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The White House (US) Executive order—HIV Care Continuum Initiative [cited 2015 Aug 2] Available from: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/07/15/executive-order-hiv-care-continuum-initiative.

- 5.The White House (US), Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy: implementation progress/federal implementation [cited 2015 Aug 2] Available from: http://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/implementation-progress/federal-implementation/index.html.

- 6.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Office of HIV/AIDS and Infectious Disease Policy Initiatives [cited 2015 Aug 2] Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ash/ohaidp/initiatives/index.html.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) National HIV Prevention Program Monitoring and Evaluation System [cited 2015 Sep 9] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/surveillance/index.html.

- 8.Hayes R, W-Jones D, Celum C, van de Wijgert J, Wasserheit J. Treatment of sexually transmitted infections for HIV prevention: end of the road or new beginning? AIDS. 2010;24:S15–26. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000390704.35642.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denning PH, DiNenno EA, Wiegand RE. Characteristics associated with HIV infection among heterosexuals in urban areas with high AIDS prevalence—24 cities, United States, 2006–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(31):1045–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System [cited 2015 Aug 2] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/surveillance/systems/index.html.

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Medical monitoring project [cited 2015 Aug 2] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/surveillance/systems/index.html.

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) HIV care saves lives [cited 2015 Aug 2] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/hiv-aids-medical-care/index.html.

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Understanding the HIV care continuum [cited 2015 Aug 2] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/dhap_continuum.pdf.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) National HIV Surveillance System [cited 2015 Jul 6] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/surveillance/index.html.

- 15.Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992;13:313–21. doi: 10.1080/07399339209516006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher HH, Hoyte T, Purcell DW, Van Handel M, Williams W, Krueger A, et al. Health department HIV prevention programs that support the National HIV/AIDS Strategy: the Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning project, 2010–2013. Public Health Rep. 2016;131:185–94. doi: 10.1177/003335491613100126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutherford GW, McFarland W, Spindler H, White K, Patel SV, A-Grasse J, et al. Public health triangulation: approach and application to synthesizing data to understand national and local HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:447. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]