Abstract

Objective

Waterpipe tobacco smoking (WTS) is an emerging trend worldwide. To inform public health policy and educational programming, we systematically reviewed the biomedical literature to compute the inhaled smoke volume, nicotine, tar, and carbon monoxide (CO) associated with a single WTS session and a single cigarette.

Methods

We searched seven biomedical bibliographic databases for controlled laboratory or natural environment studies designed to mimic human tobacco consumption. Included studies quantified the mainstream smoke of a single cigarette and/or single WTS session for smoke volume, nicotine, tar, and/or CO. We conducted meta-analyses to calculate summary estimates for the inhalation of each unique substance for each mode of tobacco consumption. We assessed between-study heterogeneity using chi-squared and I-squared statistics.

Results

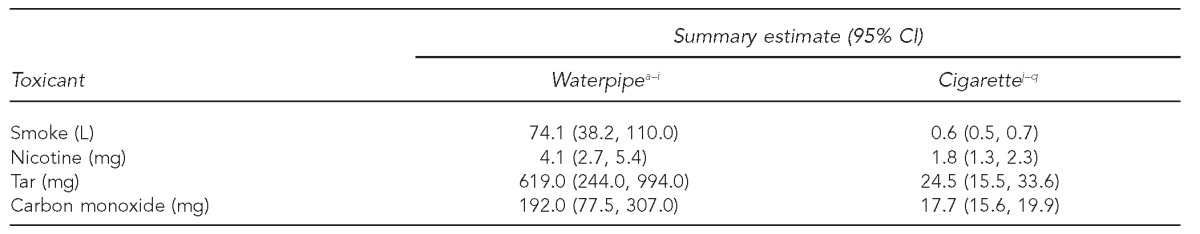

Sufficient data from 17 studies were available to derive pooled estimates for inhalation of each exposure via each smoking method. Two researchers working independently abstracted measurement of smoke volume in liters, and nicotine, tar, and CO in milligrams. All numbers included in meta-analyses matched precisely between the two researchers (100% agreement, Cohen's k=1.00). Whereas one WTS session was associated with 74.1 liters of smoke inhalation (95% confidence interval [CI] 38.2, 110.0), one cigarette was associated with 0.6 liters of smoke (95% CI 0.5, 0.7). One WTS session was also associated with higher levels of nicotine, tar, and CO.

Conclusions

One WTS session consistently exposed users to larger smoke volumes and higher levels of tobacco toxicants compared with one cigarette. These computed estimates may be valuable to emphasize in prevention programming.

Waterpipe tobacco smoking (WTS) is an emerging trend worldwide.1,2 For example, although the rate of U.S. cigarette smoking has decreased during the past two decades, national data demonstrate that ever and past 30-day WTS use among university students is 30.5% and 8.2%, respectively, making WTS the second most common type of tobacco used after cigarettes.3 In some populations, the prevalence of WTS is even higher than cigarette smoking.4,5 Although WTS previously was thought to be a phenomenon isolated to college populations, a recent national study showed that more than 20% of 12th-grade students participated in WTS in the past 12 months.6 Other studies have consistently shown substantial WTS among 6th- to 12th-grade students,7–9 as well as increasing WTS among adults who do not attend universities.10,11 Although WTS overlaps with the use of other forms of tobacco, up to half of WTS occurs without using other forms of tobacco.5,12,13 Therefore, WTS likely exposes many individuals who may otherwise have been tobacco naïve to tobacco combustion products.

Waterpipe tobacco smoke is known to contain many toxicants found in cigarette smoke, such as nicotine, tar (which is the common name for nicotine-free dry particular matter produced by the combustion of tobacco), carbon monoxide (CO), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, volatile aldehydes, phenols, and heavy metals.14–19 However, estimates vary as to the relative smoke volumes and toxicant loads associated with these modes of tobacco use based on factors such as when and where the study was conducted.20–23 Similarly, various estimates for comparisons among toxicants emitted by tobacco products have been made.15,19,21–24

To inform public health policy and educational programming, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to provide pooled estimates of relative toxicant exposures for WTS and cigarette smoking. More specifically, we computed associated smoke volume, nicotine, tar, and CO for a single WTS session and consumption of a single cigarette.

METHODS

We designed and reported this study using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).25 PRISMA was designed to guide authors in comprehensive, evidence-based systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Selection criteria

We included all studies published prior to April 2013 that (1) reported a controlled laboratory or natural environment study (i.e., a study conducted in a community-based location such as a WTS café) designed to mimic human tobacco consumption, (2) quantified the mainstream smoke of a single cigarette and/or single WTS session, and (3) reported smoke volume in liters (L), and nicotine, tar, and/or CO in milligrams (mg). For example, one recent study, which measured half a WTS session to investigate differences in charcoal emissions, was excluded because it did not measure an entire WTS session and because it was not intended to measure toxicant yield.16 We excluded studies that did not present sample sizes or sufficient information to compute means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each toxicant exposure. Study inclusion was not limited by sample size, age, sex, location of study, or language of publication.

Identification and selection of studies

We conducted the final searches of the seven databases in April 2013. Databases selected were OvidSP MEDLINE® and OvidSP MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations (both, Ovid Technologies, Inc., New York, New York), EMBASE and Scopus (both, Elsevier BV, Amsterdam), TOXLINE (TOXNET, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland), Science Citation Index Expanded (1945–present) and BIOSIS Previews (both, Web of Science, Thomson Reuters, New York, New York), and all databases of the Cochrane Library (Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey).

Specific search strategies, which are available upon request, were developed by a professional research librarian. Each strategy was designed to be broad and was tailored to the idiosyncrasies of the particular database. All searches included comprehensive lists of search terms related to WTS, to smoking, and to the various substances of interest (available upon request). Reference lists of included studies were hand-searched to identify additional relevant articles.

Ideally, we only would have included studies that measured both WTS and cigarette yield in the same study. However, only one study assessed both WTS and cigarettes in the same reports, and for one outcome only.21 Therefore, to improve quality and comparability of studies, our searches focused on capturing WTS-related studies and then searching reference lists of those articles for comparable cigarette-related articles and methodologies upon which they were based (a list of search terms is available upon request). In this way, we hoped to capture the WTS and cigarette articles that matched most closely.

Two researchers independently reviewed all articles retrieved to identify studies that met eligibility criteria. Interrater reliability was high (98% agreement, Cohen's k=0.83). For the few initial disagreements, the reviewers easily achieved consensus on eligibility.

Data extraction

Two researchers abstracted (1) study background information, such as location and year of study; (2) sample-related information, such as sample size and participant demographics; (3) toxicants tested; (4) testing apparatus and procedures; and (5) measured values for selected toxicants. Abstraction protocols called for measurement of smoke volume in liters, and nicotine, tar, and CO in milligrams. We developed structured spreadsheets to facilitate complete and accurate data collection. All numbers included in meta-analyses matched between the two researchers (100% agreement, Cohen's k=1.00).

Data analyses

We conducted meta-analyses to calculate summary estimates for the inhalation of each unique toxicant (i.e., smoke volume, nicotine, tar, and CO) for each mode of tobacco consumption (waterpipe and cigarette). Data from each study were standardized to the mean and 95% CI for each toxicant and by each mode of delivery. For each meta-analysis, we used the random-effects method of DerSimonian and Laird and assessed between-study heterogeneity using c2 and I2 statistics.26

Although the primary outcomes were the total amount of toxicant inhalation for each of the four substances of interest for all studies combined, we also performed subgroup analysis for each type of toxicant by study type (i.e., studies utilizing data from human subjects vs. machine smoking protocols). We conducted all analyses using Stata® version 11.0.27

RESULTS

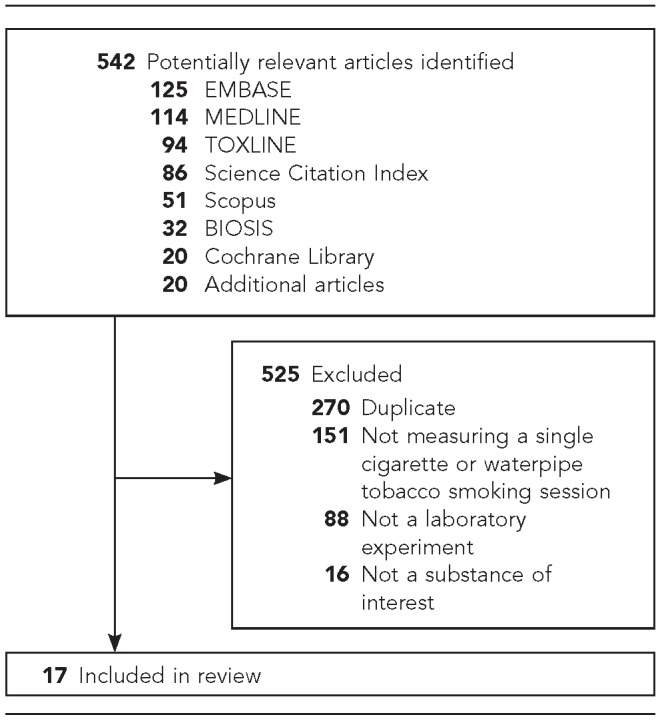

Of 542 potentially relevant published articles, 272 represented unique studies. Of these 272 unique studies, we eliminated 151 (56%) that did not measure a single cigarette or WTS session, 88 (32%) that were not laboratory experiments, and 16 (6%) that did not assess one of the substances of interest. Seventeen remaining studies were eligible for meta-analysis (Figure). Only four of the 17 included studies were located in reference lists of included studies, as opposed to the original searches themselves.

Figure.

Selection of studies in a literature review quantifying single-session waterpipe tobacco smoking and cigarette use in the United States, 2012–2015

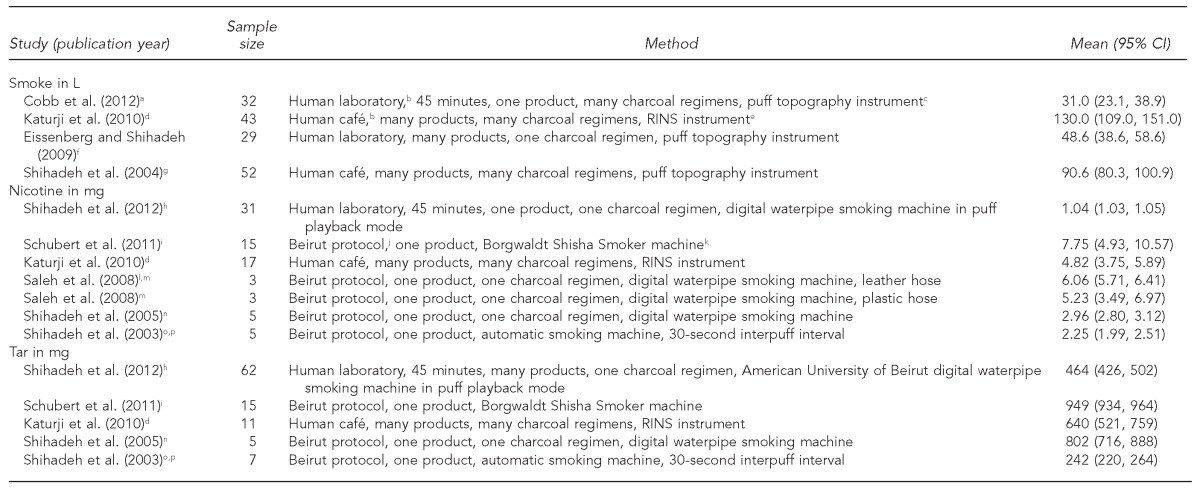

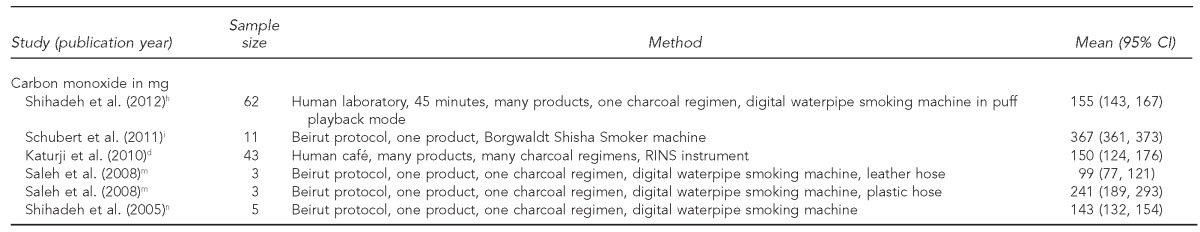

The nine WTS studies (Table 1) quantified inhalation of smoke volume (n=4),20–22,28 nicotine (n=6),18–20,29–31 tar (n=5),18–20,30,31 and CO (n=5).18,20,29–31 The eight cigarette studies quantified inhalation of smoke (n=5),21,23,32–34 nicotine (n=7),23,32–37 tar (n=7),21,32–37 and CO (n=5)23,34–37 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Studies quantifying smoke, nicotine, tar, and carbon monoxide in one waterpipe tobacco smoking session in a systematic literature review, United States, 2012–2015

aCobb CO, Sahmarani K, Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Acute toxicant exposure and cardiac autonomic dysfunction from smoking a single narghile waterpipe with tobacco and with a “healthy” tobacco-free alternative. Toxicol Lett 2012;215:70-5.

bHuman laboratory studies utilized human subjects smoking in a controlled laboratory setting, while human café studies involved human subjects in a real-life naturalistic community-based setting, such as a smoking lounge.

cA puff topography instrument is a specialized device attached to the user's waterpipe that assesses data such as the volume of smoke inhaled and the length of time between puffs (i.e., interpuff interval).

dKaturji M, Daher N, Sheheitli H, Saleh R, Shihadeh A. Direct measurement of toxicants inhaled by water pipe users in the natural environment using a real-time in situ sampling technique. Inhal Toxicol 2010;22:1101-9.

eThe RINS instrument is a type of puff topography instrument that performs RINS.

fEissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: direct comparison of toxicant exposure. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:518-23.

gShihadeh A, Azar S, Antonius C, Haddad A. Towards a topographical model of narghile water-pipe cafe smoking: a pilot study in a high socioeconomic status neighborhood of Beirut, Lebanon. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2004;79:75-82.

hShihadeh A, Salman R, Jaroudi E, Saliba N, Sepetdjian E, Blank MD, et al. Does switching to a tobacco-free waterpipe product reduce toxicant intake? A crossover study comparing CO, NO, PAH, volatile aldehydes, “tar” and nicotine yields. Food Chem Toxicol 2012;50:1494-8.

iSchubert J, Hahn J, Dettbarn G, Seidel A, Luch A, Schulz TG. Mainstream smoke of the waterpipe: does this environmental matrix reveal as significant source of toxic compounds? Toxicol Lett 2011;205:279-84.

jThe standard Beirut protocol (Katurji et al., 2010) used, unless otherwise noted, consists of 171 530-milliliter puffs of 2.6-second duration each.

kThe Borgwaldt Shisha Smoker machine (Borgwaldt, Hamburg, Germany) artificially creates inhalations designed to mimic human waterpipe tobacco smoking patterns. It was developed by Borgwaldt and is designed to standardize smoking of waterpipe tobacco to obtain reproducible results.

lSaleh et al. (2008) used two conditions (leather hose vs. plastic hose).

mSaleh R, Shihadeh A. Elevated toxicant yields with narghile waterpipes smoked using a plastic hose. Food Chem Toxicol 2008;46:1461-6.

nShihadeh A, Saleh R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, “tar,” and nicotine in the mainstream smoke aerosol of the narghile water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol 2005;43:655-61.

oShihadeh et al. (2003) used multiple interpuff intervals. The 30-second data were selected because waiting about 30 seconds between puffs most closely attempted to mimic human consumption. This study also used a different protocol consisting of 100 300-milliliter puffs of 3-second duration.

pShihadeh A. Investigation of mainstream smoke aerosol of the argileh water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol 2003;41:143-52.

CI = confidence interval

RINS = real-time in situ sampling

Table 2.

Studies quantifying smoke, nicotine, tar, and carbon monoxide in one cigarette smoking session in a systematic literature review, United States, 2012–2015

aEissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: direct comparison of toxicant exposure. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:518-23.

bHuman laboratory studies utilized human subjects smoking in a controlled laboratory setting.

cDjordjevic et al. (2000) utilized both a lower- and higher-tar condition, each of which met criteria for inclusion.

dDjordjevic MV, Stellman SD, Zang E. Doses of nicotine and lung carcinogens delivered to cigarette smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:106-11.

eTSITS refers to Djordjevic's tobacco smoke inhalation testing system, in which computer-recorded human smoking parameters are programmed into a smoking machine that mimics each recorded smoking pattern.

fDjordjevic MV, Hoffman D, Hoffman I. Nicotine regulates smoking patterns. Prev Med 1997;26:435-40.

gDjordjevic MV, Fan J, Ferguson S, Hoffman D. Self-regulation of smoking intensity. Smoke yields of the low-nicotine, low-“tar” cigarettes. Carcinogenesis 1995;16:2015-21.

hLower 95% CI limit set to zero.

iSutton SR, Russell MA, Iyer R, Feyerabend C, Saloojee Y. Relationship between cigarette yields, puffing patterns, and smoke intake: evidence for tar compensation? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:600-3.

jMoir D, Rickert WS, Levasseur G, Larose Y, Maertens R, White P, et al. A comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions. Chem Res Toxicol 2008;21:494-502.

kThe International Organization for Standardization protocol utilizes 35-milliliter puffs, 60-second intervals, and 2-second puff duration.

lThe Borgwaldt (Hamburg, Germany) smoking machines used here artificially create inhalations designed to mimic human cigarette smoking patterns. They were developed by Borgwaldt and are designed to obtain reproducible results.

mRickert WS, Trivedi AH, Momin RA, Wright WG, Lauterbach JH. Effect of smoking conditions and methods of collection on the mutagenicity and cytotoxicity of cigarette mainstream smoke. Toxicol Sci 2007;96:285-93.

nThe two products utilized were the CIM-7 flue-cured reference cigarette and the KY2R4F reference cigarette.

oRickert WS, Robinson JC, Collishaw N. Yields of tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide in the sidestream smoke from 15 brands of Canadian cigarettes. Am J Public Health 1984;74:228-31.

pThe modified ISO protocol utilized 35-milliliter puffs of 2-second duration every 58 seconds until a fixed butt length.

CI = confidence interval

TSITS = tobacco smoke inhalation testing system

ISO = International Organization for Standardization

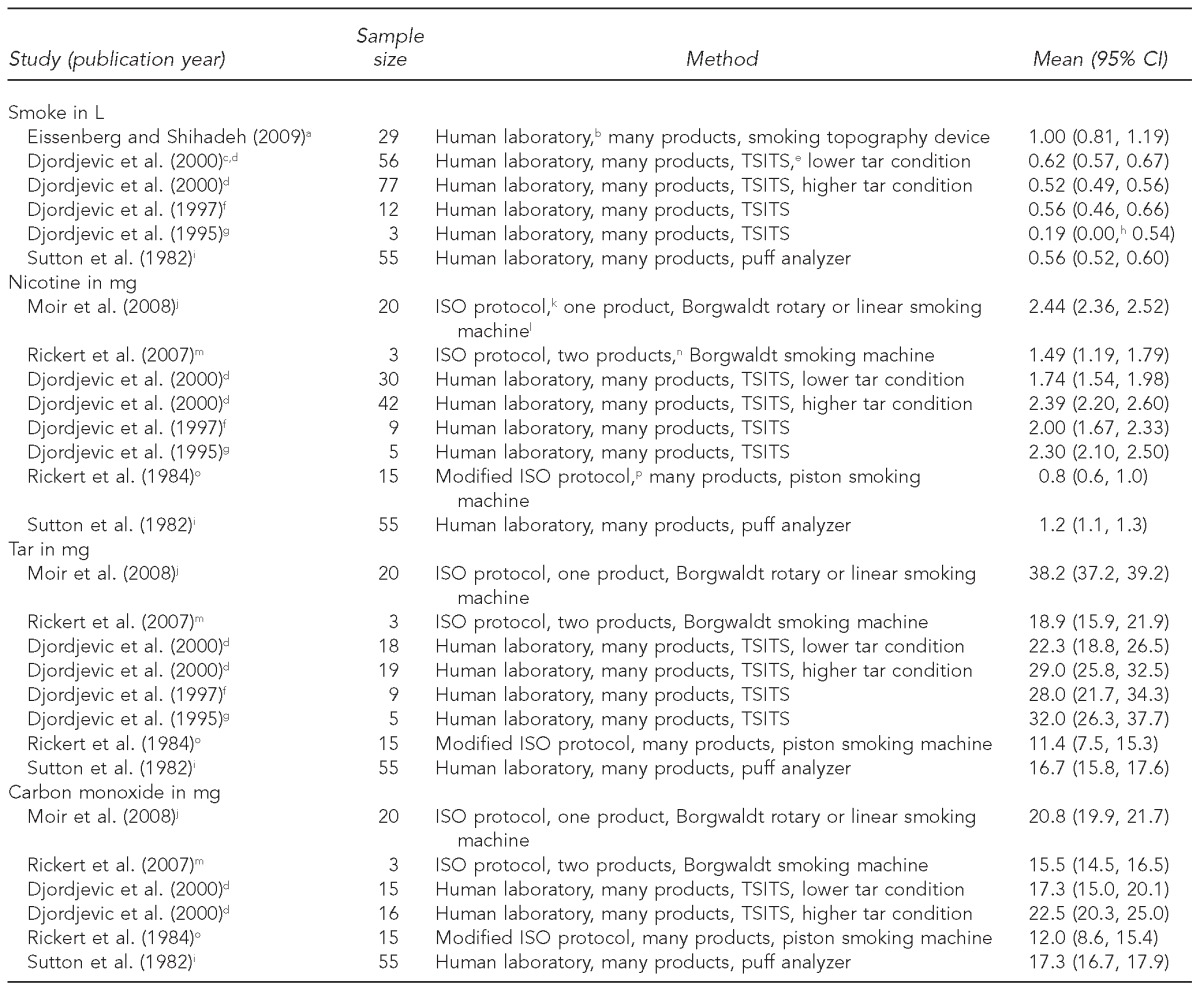

We found significant between-study heterogeneity in measured toxicant inhalation for each type of toxicant (all p<0.001). Whereas one WTS session was associated with 74.1 L of smoke inhalation (95% CI 38.2, 110.0), one cigarette was associated with 0.6 L of smoke (95% CI 0.5, 0.7). Other toxicant estimates and 95% CIs similarly demonstrated greater values for one WTS session compared with a single cigarette (Table 3).

Table 3.

Meta-analysis summary estimates based on 17 studies identified in a systematic literature review that quantified toxicant loads associated with a single waterpipe tobacco smoking session and a single cigarette, United States, 2012–2015

aCobb CO, Sahmarani K, Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Acute toxicant exposure and cardiac autonomic dysfunction from smoking a single narghile waterpipe with tobacco and with a “healthy” tobacco-free alternative. Toxicol Lett 2012;215:70-5.

bEissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: direct comparison of toxicant exposure. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:518-23.

cKaturji M, Daher N, Sheheitli H, Saleh R, Shihadeh A. Direct measurement of toxicants inhaled by water pipe users in the natural environment using a real-time in situ sampling technique. Inhal Toxicol 2010;22:1101-9.

dSaleh R, Shihadeh A. Elevated toxicant yields with narghile waterpipes smoked using a plastic hose. Food Chem Toxicol 2008;46:1461-6.

eSchubert J, Hahn J, Dettbarn G, Seidel A, Luch A, Schulz TG. Mainstream smoke of the waterpipe: does this environmental matrix reveal as significant source of toxic compounds? Toxicol Lett 2011;205:279-84.

fShihadeh A. Investigation of mainstream smoke aerosol of the argileh water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol 2003;41:143-52.

gShihadeh A, Azar S, Antonius C, Haddad A. Towards a topographical model of narghile water-pipe cafe smoking: a pilot study in a high socioeconomic status neighborhood of Beirut, Lebanon. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2004;79:75-82.

hShihadeh A, Saleh R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, “tar,” and nicotine in the mainstream smoke aerosol of the narghile water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol 2005;43:655-61.

iShihadeh A, Salman R, Jaroudi E, Saliba N, Sepetdjian E, Blank MD, et al. Does switching to a tobacco-free waterpipe product reduce toxicant intake? A crossover study comparing CO, NO, PAH, volatile aldehydes, “tar” and nicotine yields. Food Chem Toxicol 2012;50:1494-8.

jDjordjevic MV, Fan J, Ferguson S, Hoffman D. Self-regulation of smoking intensity. Smoke yields of the low-nicotine, low-“tar” cigarettes. Carcinogenesis 1995;16:2015-21.

kDjordjevic MV, Hoffman D, Hoffman I. Nicotine regulates smoking patterns. Prev Med 1997;26:435-40.

lDjordjevic MV, Stellman SD, Zang E. Doses of nicotine and lung carcinogens delivered to cigarette smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:106-11.

mEissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: direct comparison of toxicant exposure. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:518-23.

nMoir D, Rickert WS, Levasseur G, Larose Y, Maertens R, White P, et al. A comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions. Chem Res Toxicol 2008;21:494-502.

oRickert WS, Robinson JC, Collishaw N. Yields of tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide in the sidestream smoke from 15 brands of Canadian cigarettes. Am J Public Health 1984;74:228-31.

pRickert WS, Trivedi AH, Momin RA, Wright WG, Lauterbach JH. Effect of smoking conditions and methods of collection on the mutagenicity and cytotoxicity of cigarette mainstream smoke. Toxicol Sci 2007;96:285-93.

qSutton SR, Russell MA, Iyer R, Feyerabend C, Saloojee Y. Relationship between cigarette yields, puffing patterns, and smoke intake: evidence for tar compensation? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:600-3.

CI = confidence interval

In a subgroup analysis for each type of toxicant by study type, for smoke volume, we did not find enough studies to be able to make comparisons. However, the number of studies was sufficient to quantify inhalation of each type of toxicant other than smoke volume to conduct subgroup meta-analyses. These analyses indicated no significant differences between these types of studies.

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis comparing common toxicant exposures in WTS and cigarette smoking demonstrated consistently higher exposures in a WTS session compared with smoking a single cigarette, with large variation in the relative exposures by toxicant type. As indicated by I2 statistics, we found significant between-study heterogeneity in measured inhalation for each type of toxicant evaluated. While significant between-study heterogeneity did not affect point estimates, it is reflected in the width of the computed 95% CIs.

These results suggest potential health concerns posed by WTS and that it should be monitored more than it is currently. For example, while the 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey System Questionnaire assesses cigarette smoking, chewing tobacco, electronic cigarettes, and many other forms of substance abuse, it does not assess WTS.38 Similarly, although Monitoring the Future began assessing WTS in 2012, surveillance is currently limited to a subsample of 12th graders.39

The estimates provided in this study may be valuable for educational and media-based interventions to reduce WTS. Estimates used in these cases should be as accurate as possible, based on a rigorous evaluation of evidence from the scientific literature, for which meta-analysis is the gold standard.40 It will be valuable to repeat these analyses periodically, however, to determine whether or not the estimates change. For example, as cigarette makers have done in the past, waterpipe tobacco makers may utilize additives that can affect toxicant yields. Additionally, it would be valuable to repeat these analyses when sufficient data are available to compare content of other toxicants, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heavy metals.

Our findings related to smoke volume are consistent with prior estimates. For example, the World Health Organization has estimated that the smoke inhalation with a single WTS session was approximately 100–200 times that consumed in a single cigarette.2 One study suggested a lower ratio, approximately 50 times the smoke inhalation.21 However, this difference may have been driven by the fact that the participants were less experienced WTS users, compared with other studies, and drew comparatively fewer puffs per minute. Therefore, although the meta-analysis findings seem consistent with other estimates, it is worth noting that such comparisons will be driven by frequency of inhalation, which will be associated with prior experience.

Nicotine values are also consistent with prior estimates.2 The lower ratio of nicotine inhalation in a single WTS session compared with a single cigarette, compared with the total smoke volume, suggests that waterpipe tobacco smoke has a smaller concentration of nicotine than cigarette smoke. However, this finding does not suggest that WTS is somehow less addictive, and it should be considered along with two important facts. First, each WTS session is associated with inhalation of two or three cigarettes' worth of nicotine, and even the occasional use of this amount of nicotine has been associated with the development of addiction, especially in young people.41 Second, another study demonstrated that the blood nicotine level of an individual after a WTS session was similar to that of a person with a 10-cigarette-per-day habit,42 suggesting that this level of inhaled toxicants may be associated with substantial plasma levels. Other studies found substantial blood and urine levels of other toxicants and their metabolites.28,42–45 Results for tar and CO were also consistent with prior estimates.2 Importantly, reports of severe CO toxicity in WTS users have been made,46 and charcoal combustion seems to be the major source of CO in waterpipe smoke.16

Although estimates across studies were roughly similar, we found significant between-study heterogeneity, as indicated by high I2 values.26 This variation could be explained by many possible sources, including differences in inhalation frequency, inhalation depth, and interpuff interval (defined as the length of time between puffs), all of which may be associated with prior experience. Toxicant yield may also change with the type of tobacco, additives used, waterpipe design, and nicotine content. For example, waterpipe tobacco smokers in one study had a relatively low total volume of inhalation (31 L), which may have resulted from downward titration in puff volume due to the high nicotine content of the tobacco used in this study.28

Limitations

An important caveat of our findings was that we compared one WTS session with a single cigarette. This comparison was somewhat inevitable because researchers in this area commonly report data for a complete WTS session and a single cigarette (instead of, for example, a single puff of waterpipe tobacco smoke or a single puff of cigarette smoke). However, it should be recognized that, because of differences in smoking patterns between waterpipes and cigarettes, direct comparisons are complex. For example, a frequent cigarette smoker may consume 15–25 cigarettes per day, while a frequent waterpipe tobacco smoker may consume only 3–6 waterpipe tobacco bowls per day, which last longer and are more complicated to load and light. Such comparisons are also difficult to make because, although a cigarette consists of about one gram of tobacco, a WTS bowl contains about 10–20 grams of tobacco; however, most of this increase is because the tobacco is moistened and sweetened. Therefore, in the future, it may be valuable to gather detailed behavioral information about usage patterns in a sample to truly estimate the relative total dose of inhaled toxicants in a population.

Another limitation of this study was the fact that we examined an inhaled toxicant as opposed to an in vivo toxicant. Because studies examining in vivo toxicants are currently highly varied in their methodologies, it was not feasible to combine the values found in those studies with inhaled toxicant values in this meta-analysis at this time. While indications are that the amount of inhaled substance is strongly associated with in vivo measures,47 differences exist between the two. Therefore, future studies should examine in vivo toxicants when data are sufficient.

A final caveat of this study was that our sample relied heavily on studies conducted using a standard smoking protocol on a machine for both cigarette and WTS. For example, nearly all WTS studies assessing tar and nicotine utilized protocol smoking, and many of the protocol studies used similar methodologies. However, our estimates were similar between human and protocol studies, as has been previously reported.47,48

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

These findings suggest that waterpipe tobacco users are exposed to high toxicant loads. Because many users are unaware of the associated toxicant load and perceive WTS as a safe alternative to cigarette smoking10,49,50 the estimates presented in this article may be valuable for educational and media-based interventions to reduce WTS.

Footnotes

The authors acknowledge receipt of funding from the National Cancer Institute (R01-CA140150). The funders played no role in the conception, data collection, writing, or approval of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maziak W. The global epidemic of waterpipe smoking. Addict Behav. 2011;36:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2005. TobReg advisory note: waterpipe tobacco smoking: health effects, research needs and recommended actions by regulators. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Primack BA, Shensa A, Kim KH, Carroll MV, Hoban MT, Leino EV, et al. Waterpipe smoking among U.S. university students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:29–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sidani JE, Shensa A, Primack BA. Substance and hookah use and living arrangement among fraternity and sorority members at US colleges and universities. J Community Health. 2013;38:238–45. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9605-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Primack BA, Sidani J, Agarwal AA, Shadel WG, Donny EC, Eissenberg TE. Prevalence of and associations with waterpipe tobacco smoking among U.S. university students. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:81–6. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan Institute for Social Research; 2015. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975–2014. Also available from: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2014.pdf [cited 2015 Jul 21] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith JR, Edland SD, Novotny TE, Hofstetter CR, White MM, Lindsay SP, et al. Increasing hookah use in California. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1876–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Primack BA, Walsh M, Bryce C, Eissenberg T. Water-pipe tobacco smoking among middle and high school students in Arizona. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e282–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnett TE, Curbow BA, Weitz JR, Johnson TM, Smith-Simone SY. Water pipe tobacco smoking among middle and high school students. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2014–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aljarrah K, Ababneh ZQ, Al-Delaimy WK. Perceptions of hookah smoking harmfulness: predictors and characteristics among current hookah users. Tob Induc Dis. 2009;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith-Simone SY, Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:393–8. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith JR, Novotny TE, Edland SD, Hofstetter CR, Lindsay SP, Al-Delaimy WK. Determinants of hookah use among high school students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:565–72. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fielder RL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Predictors of initiation of hookah tobacco smoking: a one-year prospective study of first-year college women. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26:963–8. doi: 10.1037/a0028344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al Rashidi M, Shihadeh A, Saliba NA. Volatile aldehydes in the mainstream smoke of the narghile waterpipe. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:3546–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cobb CO, Shihadeh A, Weaver MF, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking and cigarette smoking: a direct comparison of toxicant exposure and subjective effects. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:78–87. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monzer B, Sepetdjian E, Saliba N, Shihadeh A. Charcoal emissions as a source of CO and carcinogenic PAH in mainstream narghile waterpipe smoke. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:2991–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sepetdjian E, Saliba N, Shihadeh A. Carcinogenic PAH in waterpipe charcoal products. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:3242–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shihadeh A, Saleh R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, “tar,” and nicotine in the mainstream smoke aerosol of the narghile water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43:655–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shihadeh A. Investigation of mainstream smoke aerosol of the argileh water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol. 2003;41:143–52. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katurji M, Daher N, Sheheitli H, Saleh R, Shihadeh A. Direct measurement of toxicants inhaled by water pipe users in the natural environment using a real-time in situ sampling technique. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:1101–9. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.524265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: direct comparison of toxicant exposure. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:518–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shihadeh A, Azar S, Antonius C, Haddad A. Towards a topographical model of narghile water-pipe cafe smoking: a pilot study in a high socioeconomic status neighborhood of Beirut, Lebanon. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Djordjevic MV, Stellman SD, Zang E. Doses of nicotine and lung carcinogens delivered to cigarette smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:106–11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sepetdjian E, Shihadeh A, Saliba NA. Measurement of 16 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in narghile waterpipe tobacco smoke. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:1582–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.StataCorp. College Station (TX): StataCorp; 2009. Stata®: Release 11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cobb CO, Sahmarani K, Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Acute toxicant exposure and cardiac autonomic dysfunction from smoking a single narghile waterpipe with tobacco and with a “healthy” tobacco-free alternative. Toxicol Lett. 2012;215:70–5. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saleh R, Shihadeh A. Elevated toxicant yields with narghile waterpipes smoked using a plastic hose. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:1461–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schubert J, Hahn J, Dettbarn G, Seidel A, Luch A, Schulz TG. Mainstream smoke of the waterpipe: does this environmental matrix reveal as significant source of toxic compounds? Toxicol Lett. 2011;205:279–84. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shihadeh A, Salman R, Jaroudi E, Saliba N, Sepetdjian E, Blank MD, et al. Does switching to a tobacco-free waterpipe product reduce toxicant intake? A crossover study comparing CO, NO, PAH, volatile aldehydes, “tar” and nicotine yields. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:1494–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Djordjevic MV, Hoffman D, Hoffman I. Nicotine regulates smoking patterns. Prev Med. 1997;26:435–40. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Djordjevic MV, Fan J, Ferguson S, Hoffman D. Self-regulation of smoking intensity. Smoke yields of the low-nicotine, low-“tar” cigarettes. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2015–21. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.9.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sutton SR, Russell MA, Iyer R, Feyerabend C, Saloojee Y. Relationship between cigarette yields, puffing patterns, and smoke intake: evidence for tar compensation? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:600–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6342.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rickert WS, Robinson JC, Collishaw N. Yields of tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide in the sidestream smoke from 15 brands of Canadian cigarettes. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:228–31. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.3.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moir D, Rickert WS, Levasseur G, Larose Y, Maertens R, White P, et al. A comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:494–502. doi: 10.1021/tx700275p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rickert WS, Trivedi AH, Momin RA, Wright WG, Lauterbach JH. Effect of smoking conditions and methods of collection on the mutagenicity and cytotoxicity of cigarette mainstream smoke. Toxicol Sci. 2007;96:285–93. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS): YRBS questionnaire content, 1991–2015. 2014 [cited 2015 Jul 21] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/crosswalk_1991-2015.pdf.

- 39.Primack BA, Freedman-Doan P, Sidani JE, Rosen D, Shensa A, James AE, et al. Sustained waterpipe tobacco smoking and trends over time among US high school seniors: findings from Monitoring the Future. Am J Prev Med. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.030. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F. New York: Wiley; 2000. Methods for meta-analysis in medical research. [Google Scholar]

- 41.DiFranza JR, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, Ockene JK, Savageau JA, St Cyr D, et al. Initial symptoms of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Tob Control. 2000;9:313–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shafagoj YA, Mohammed FI. Levels of maximum end-expiratory carbon monoxide and certain cardiovascular parameters following hubble-bubble smoking. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:953–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maziak W, Rastam S, Shihadeh AL, Bazzi A, Ibrahim, Zaatari GS, et al. Nicotine exposure in daily waterpipe smokers and its relation to puff topography. Addict Behav. 2011;36:397–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blank MD, Cobb CO, Kilgalen B, Austin J, Weaver MF, Shihadeh A, et al. Acute effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking: a double-blind, placebo-control study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116:102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vansickel AR, Shihadeh A, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco products: nicotine labelling versus nicotine delivery. Tob Control. 2012;21:377–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.042416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turkmen S, Eryigit U, Sahin A, Yeniocak S, Turedi S. Carbon monoxide poisoning associated with water pipe smoking. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011;49:697–8. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.598160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shihadeh A, Eisenberg TE. Significance of smoking machine toxicant yields to blood-level exposure in water pipe tobacco smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2457–60. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neergaard J, Singh P, Job J, Montgomery S. Waterpipe smoking and nicotine exposure: a review of the current evidence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:987–94. doi: 10.1080/14622200701591591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Korn L, Magnezi R. Cigarette and nargila (water pipe) use among Israeli Arab high school students: prevalence and determinants of tobacco smoking. Scientific World J. 2008;8:517–25. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakkash RT, Khalil J, Affifi RA. The rise in narghile (shisha, hookah) waterpipe tobacco smoking: a qualitative study of perceptions of smokers and non smokers. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:315. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]