Abstract

Objective

We determined whether or not HIV testing in publicly funded settings in the United States increased after 2006, when CDC recommended expanded HIV screening in health-care settings for all people aged 13–64 years.

Methods

We analyzed 2003–2010 National Health Interview Survey data to estimate annual national percentages of people aged 18–64 years who were tested for HIV in the previous 12 months. Estimates were calculated by setting (publicly funded, yes/other) and stratified by sex. Test settings were categorized as publicly funded based on the contribution of public funds for HIV testing. We used logistic regression modeling to assess statistical significance in linear trends for 2003–2006 and 2006–2010, adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, and health insurance coverage. Using model parameters for survey year, we calculated the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) in HIV testing as the difference in the model-predicted testing prevalence between baseline and first post-baseline years, divided by baseline prevalence.

Results

During 2006–2010, the percentage of women tested for HIV in publicly funded settings increased significantly from 1.9% in 2006 to 2.4% in 2010 (EAPC=6.9%, p=0.008) and the percentage tested in other settings remained fairly stable, from 9.7% in 2006 to 9.6% in 2010 (EAPC=–0.5%, p=0.708). During the same period, the percentage of men tested for HIV in publicly funded settings increased, but not significantly, from 1.5% in 2006 to 1.9% in 2010 (EAPC=5.3%, p=0.110) and the percentage tested in other settings decreased significantly from 7.5% in 2006 to 6.2% in 2010 (EAPC=–4.4%, p=0.001).

Conclusion

Although HIV testing in publicly funded settings increased among women during 2006–2010, testing rates remained low, and no similar increase occurred among men. As such, all test settings should increase HIV screening, particularly for men.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing is the entry point into the continuum of HIV care that includes diagnosis, linkage to and retention in HIV medical care, prevention counseling, and antiretroviral therapy to achieve viral suppression.1 When diagnosis is made at an early stage in HIV progression and the HIV-infected person begins antiretroviral therapy immediately, he/she is likely to have lower morbidity, increased survival,2–4 and a lower risk of sexual transmission than if the diagnosis is made at a later stage of HIV infection.2,3 Additionally, people who are aware of their HIV infection are less likely to engage in high-risk sexual behaviors than people who are unaware of their HIV infection.5 Despite the individual and public health benefits of HIV testing and early diagnosis of HIV infection, one in six (15.8%) of the estimated 1,144,500 people aged ≥13 years living with HIV infection in the United States in 2010 was unaware of their infection and in need of HIV testing, diagnosis, and treatment. An estimated 81.5% of people with undiagnosed infection in 2010 were men.6

To increase HIV screening, in 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that health-care settings implement routine, opt-out HIV testing for adolescents and adults aged 13–64 years, regardless of risk, where prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection is ≥0.1%. The goals of CDC's revised recommendations were to facilitate earlier detection of HIV infection, counsel people newly diagnosed with HIV infection and link them to care, and further reduce perinatal transmission of HIV. The revised recommendations supported opt-out screening, where testing is performed unless the patient declines, and encouraged removing requirements for separate written consent for HIV testing and for pretest prevention counseling.7

Since the release of the revised recommendations, CDC has supported their implementation through the Expanded Testing Initiative (ETI) launched in 2007. In the first three years of ETI, CDC provided an additional $111 million to health departments in 25 U.S. jurisdictions. Under ETI, health departments were funded to increase the number of people tested, particularly people disproportionately affected by HIV (i.e., black/African Americans, those self-identifying as Hispanic/Latino, and gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men [collectively referred to as MSM]), and to support implementation of the revised recommendations for routine screening in clinical settings. Health departments were required to focus at least 80% of their activities on promoting opt-out HIV screening in high-morbidity clinical settings.8 In addition to ETI funding, CDC supported health department grantees to conduct routine and targeted HIV testing in various settings, including HIV testing and counseling venues, public health departments, community health clinics, family planning and prenatal clinics, drug treatment facilities, and sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics. Many of these sites rely on public funds to provide HIV testing to clients (hereinafter referred to as publicly funded settings).

Grantees funded by CDC to conduct HIV testing may be more aware of CDC's recommendations than test venues that pay for HIV testing with other funds (e.g., third-party reimbursement) and can access technical assistance to establish routine HIV screening. However, no studies have evaluated trends in the annual percentage of people tested for HIV in publicly funded settings in the United States after the release of the revised recommendations. (However, a special supplemental issue on HIV testing accompanies this issue of Public Health Reports.) The purpose of this study was to determine if HIV testing in publicly funded settings increased following release of the revised recommendations for HIV screening and provision of funding to support their implementation (e.g., ETI). We hypothesized that HIV testing increased in publicly funded settings since 2006. Some publicly funded settings include clinical venues that focus on care for reproductive-aged women (e.g., family planning and prenatal clinics); therefore, we assessed trends in HIV testing separately for men and women.

METHODS

Data source

We analyzed data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) for 2003–2010 for people living in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. NHIS is an ongoing, annual, cross-sectional household interview survey that collects information on a wide range of health topics. Using a multistage area probability design, NHIS obtains a nationally representative sample of civilian, noninstitutionalized U.S. households. The annual NHIS response rates ranged from 74.2% in 2003 to 60.8% in 2010.9

Statistical analysis

Inclusion criteria.

This analysis was based on three inclusion criteria. First, only respondents aged 18–64 years were included, to align with the age group represented in NHIS (i.e., ≥18 years of age) and for which CDC's revised recommendations encourage HIV screening (i.e., 13–64 years of age) (n=175,470). Second, respondents had to provide a yes/no response to whether or not they had ever been tested for HIV, excluding tests for blood donations (e.g., don't know or refused excluded) (n=168,516, 96.0%). Lastly, for those reporting a previous HIV test, the respondent had to provide either a valid estimated time period since their most recent HIV test or a valid month (e.g., January through December) and year (e.g., 1985 to interview year) for their most recent HIV test (n=165,349, 94.2%).

We assessed the percentage of people aged 18–64 years who were tested for HIV in the previous 12 months overall, in publicly funded settings, and in settings that were not primarily publicly funded (hereinafter referred to as “other settings”) for each year from 2003 to 2010. We defined respondents who were tested for HIV in the previous 12 months as those who reported having ever been tested for HIV and whose most recent HIV test was within 12 months of the interview date.

The test venue of their most recent HIV test was categorized as publicly funded settings or other settings. For the purposes of this analysis, publicly funded settings included acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) clinic/counseling/testing sites, public health departments, community health clinics, family planning and prenatal clinics, drug treatment facilities, STD clinics, and tuberculosis clinics. Other settings included private doctor/health maintenance organizations, hospital/emergency room/outpatient clinics, homes, military induction/service sites, immigration sites, correctional facilities, employer- or insurance company-run clinics, and other unspecified locations. Some of the other settings (e.g., correctional facilities and military induction/service sites) may receive federal funds, but we categorized them as other settings because the purpose of the publicly funded settings category was to capture settings whose funding for HIV testing was primarily supported through public health HIV prevention funding.10

Data analysis

We used SAS® version 9.3 to analyze data weighted to represent all U.S. adults aged 18–64 years and to adjust standard errors to account for the complex sampling design.11 From 2003 to 2010, the annual percentage and estimated number of people who reported being tested for HIV in the previous 12 months were calculated overall and for publicly funded and other settings. All analyses were stratified by sex. We calculated the average annual increase in the number of people tested during the time period by calculating the total change that accrued during the time period divided by the number of years (beyond the baseline year).

To compare trends before and after release of CDC's revised recommendations, we conducted trend analyses for 2003–2006 and 2006–2010.12,13 We included the year the revised recommendations were released, 2006, in both time periods as the last year before the revised recommendations were released for the first time period and as a baseline year for the latter time period. We assessed significant linear trends in HIV testing stratified by sex using separate logistic regression models overall and for each setting, with survey year as the continuous, independent variable. We adjusted the final models for age group, race/ethnicity, and having any health insurance coverage, because these variables were identified as potential confounders in HIV testing by setting. We coded the outcome variable as a binary indicator. We used the beta coefficient of the survey year with a standard intercept from the logistic regression models adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, and insurance coverage to calculate the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) by subtracting the model-predicted baseline prevalence (Ry) from the predicted year-one prevalence (Ry+1) and dividing this difference by the predicted baseline prevalence (Ry):12

RESULTS

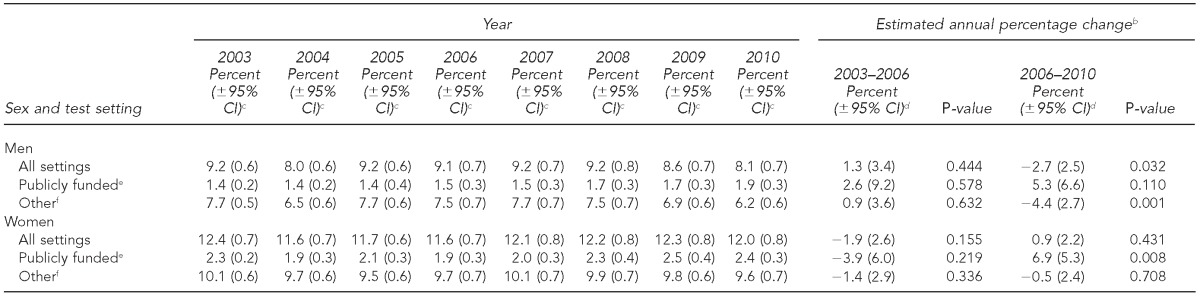

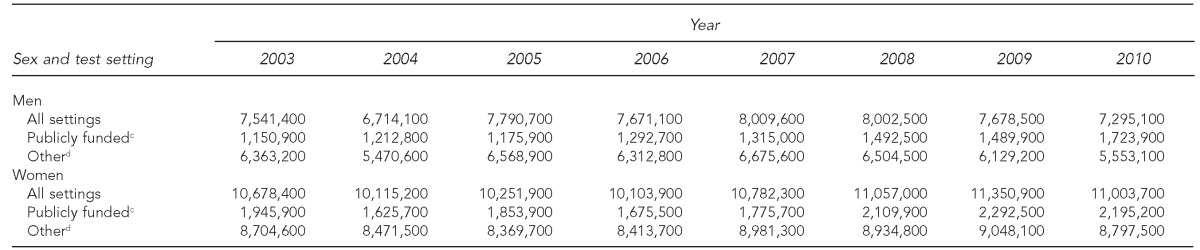

During 2003–2006, before release of CDC's revised recommendations, the percentage of men tested for HIV in the previous 12 months in all settings, in publicly funded settings, and in other settings did not change significantly. The percentage of men tested for HIV in the previous 12 months in all settings decreased significantly from 9.1% in 2006 to 8.1% in 2010 (EAPC=–2.7%, p=0.032). The percentage of men tested in publicly funded settings increased, albeit not significantly, from 1.5% in 2006 to 1.9% in 2010 (EAPC=5.3%, p=0.110). The percentage of men tested in other settings decreased significantly from 7.5% in 2006 to 6.2% in 2010 (EAPC=–4.4%, p=0.001) (Table 1). This decrease represented an average annual decrease of 189,900 fewer men tested in other settings, from 6,312,800 in 2006 to 5,553,100 in 2010 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Percentage of U.S. adults aged 18–64 years who tested for HIV in the previous 12 months, by test setting,a National Health Interview Survey, 2003–2010

The percentage of people tested for HIV in the previous 12 months in publicly funded settings and other settings may not sum to the percentage for all settings due to missing information for the last test setting venue.

bAll logistic regression models were adjusted for age group, race/ethnicity, and health insurance coverage.

cThe half-width of the 95% CI for the annual percentage tested was calculated from weighted estimates and standard errors that account for the complex sample design.

dThe half-width of the 95% CI for the estimated annual percentage change was calculated using the regression coefficient and its standard error from adjusted models and the baseline percentage for each time period.

ePublicly funded settings included acquired immunodeficiency syndrome clinic/counseling/testing sites, public health departments, community health clinics, family planning and prenatal clinics, drug treatment facilities, sexually transmitted disease clinics, and tuberculosis clinics.

fOther settings included private doctor/health maintenance organizations, hospital/emergency room/outpatient clinics, homes, military induction/service sites, immigration sites, correctional facilities, employer- or insurance company-run clinics, and other unspecified locations.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

CI = confidence interval

Table 2.

Estimated number of U.S. adults aged 18–64 yearsa who tested for HIV in the previous 12 months, by test setting,b National Health Interview Survey, 2003–2010

National Health Interview Survey data were weighted to represent all U.S. adults aged 18–64 years and to adjust standard errors to account for the complex sample design; estimates for those tested for HIV in the previous 12 months by sex and test setting were rounded to the hundred to avoid false precision.

The estimated number of people tested for HIV in the previous 12 months in publicly funded settings and other settings may not sum to the estimated number for all settings due to missing information for the last test setting venue.

cPublicly funded settings included acquired immunodeficiency syndrome clinic/counseling/testing sites, public health departments, community health clinics, family planning and prenatal clinics, drug treatment facilities, sexually transmitted disease clinics, and tuberculosis clinics.

dOther settings included private doctor/health maintenance organizations, hospital/emergency room/outpatient clinics, homes, military induction/service sites, immigration sites, correctional facilities, employer- or insurance company-run clinics, and other unspecified locations.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

During 2003–2006, the percentage of women tested for HIV in the previous 12 months in all settings, in publicly funded settings, and in other settings was stable. During 2006–2010, the percentage of women tested for HIV in the previous 12 months in all settings was stable at 12.0% (range: 11.6% to 12.3%) (EAPC=0.9%, p=0.431). The percentage of women tested in publicly funded settings increased significantly from 1.9% in 2006 to 2.4% in 2010 (EAPC=6.9%, p=0.008) (Table 1). This increase represented an -average annual increase of 129,900 more women tested in publicly funded settings, from 1,675,500 in 2006 to 2,195,200 in 2010 (Table 2). The percentage of women tested in other settings was stable during 2006–2010 at 9.8% (range: 9.6% to 10.1%) (EAPC=–0.5%, p=0.708) (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

After release of CDC's revised recommendations for HIV screening in 2006, HIV testing in the previous 12 months in publicly funded settings increased significantly among women by 6.9% annually from 1.9% in 2006 to 2.4% in 2010. Although small, this percentage increase translated to an average annual increase of nearly 130,000 more women obtaining an HIV test in the previous 12 months in publicly funded settings. The 5.3% annual increase observed among men testing for HIV in the previous 12 months in publicly funded settings was not significant, but the increase was consistent with the findings among women. However, the percentage of men tested in the previous 12 months in other settings decreased significantly by 4.4% annually during 2006–2010. This finding suggests a lack of wide-scale adoption of CDC's revised recommendations for routine HIV screening among men or that men may not have gone to settings where routine screening was conducted.

Following years of stable HIV testing during 2003–2006, the increased focus on HIV testing through CDC's revised recommendations for HIV screening, additional CDC funding for HIV testing, and access to technical assistance for implementing HIV testing programs may have contributed to the increase in HIV testing in publicly funded settings among women. The trend among men showed an increase that was not significant. Annually, we estimated that nearly 240,000 more people tested for HIV in publicly funded settings. Our results are supported by CDC's HIV testing program data that showed approximately 260,000 more tests were conducted in CDC-funded settings annually from 2006 to 2010.14,15 Although CDC measured the number of tests conducted and we measured the number of people tested, the similarity in the estimates supports our conclusion that testing has increased in publicly funded settings.

CDC's ETI directly contributed to testing resources for publicly funded settings. As of September 2010, venues that we categorized as publicly funded settings represented nearly 60% of the venues funded by ETI and nearly half of the 2.8 million ETI-funded testing events conducted. One goal of ETI was to expand opportunities for routine HIV screening to clinical venues that serve high HIV-prevalence communities. As such, the other 40% of venues funded by ETI were venues, such as emergency departments and primary care clinics, that have not traditionally been funded by CDC.8 Although CDC increased the emphasis on routine HIV screening, and the national incidence rate of HIV infection has decreased in recent years, the yield of HIV-positive tests only decreased by 212 annually (from 25,675 [1.2%] tests confirmed HIV-positive in 2006 to 24,828 [0.8%] tests confirmed HIV-positive in 2010).14–16

Other studies have shown that publicly funded test settings, such as community health clinics, have increased HIV screening as recommended by CDC.17,18 Myers et al. demonstrated that CDC's revised recommendations can be integrated into community health centers using rapid test technology to provide access to HIV testing for people not previously tested. Across six community health centers, of the 16,148 tests offered to patients aged 13–64 years during March 2007 and March 2008, 10,769 (67%) tests were performed compared with 3% of patients tested during the previous year.17 A separate study also demonstrated acceptability of routine HIV screening in community health clinics in urban, suburban, and rural areas in South Carolina; on average, 58% of patients were screened during the first eight months (December 2006–July 2007) of implementation of the routing screening program.18

The increase in HIV testing in publicly funded settings was likely higher among women than among men because some of the publicly funded settings focus on providing prenatal and family planning services. In 2006, 13% of HIV tests conducted in publicly funded settings were in family planning and prenatal clinics.10 HIV screening has been recommended for all pregnant women, regardless of risk, since 1995, and an HIV test is often included in the routine panel of screening tests for pregnant women.19 Because routine screening during pregnancy has been recommended for a longer period of time, routine prenatal HIV screening is more commonly reimbursed by third-party payers than routine HIV screening for men and for non-pregnant women. As of 2015, all state Medicare programs must cover one annual HIV screening for people aged 15–65 years and up to three HIV tests for women during each pregnancy.20 However, as of 2013, only 35 state Medicaid programs supported routine HIV screening for men and women regardless of risk.21 In other settings, our study found that testing in the previous 12 months was stable among women and decreased significantly among men.

The significant decrease in the percentage of men tested in the previous 12 months in other settings translated to nearly 190,000 fewer men tested annually, more than the increase in men tested in publicly funded settings. The decrease in testing among men in other settings may reflect a lack of provider awareness of CDC's recommendations, increased barriers to implementing routine HIV screening in other settings, and decreasing knowledge about and perception of HIV risk, particularly among young adult men.

Nationally, awareness of CDC's 2006 revised recommendations to conduct HIV screening on all people aged 13–64 years, regardless of risk, among primary care physicians, emergency department doctors, and internists is low.22,23 Since the recommendations to screen pregnant women were released in 1995, women of reproductive age have been tested at higher rates than men.24 Despite efforts to increase routine HIV screening among all people aged 13–64 years, the practices used to routinely screen women have not been adopted for men. Provider education campaigns should be conducted to increase knowledge of current HIV testing recommendations, state HIV testing policies, and reimbursement options for routine HIV screening. Although the CDC ETI funds directed toward other settings were intended to expand HIV testing opportunities and reduce financial barriers, these funds may have been insufficient to fill the gap caused by an increasing number of states with no state or local funding for HIV prevention.25

In addition to health-care providers' lack of awareness of CDC's revised recommendations and reduced local resources for HIV prevention, studies have demonstrated differences by sex among young adults and adolescents with regard to knowledge and perception of HIV risk. Among low-income African American adolescents, girls had higher levels of HIV knowledge than boys, and HIV knowledge was positively associated with HIV testing.26 In addition, one study showed that women were more likely to be offered or initiate an HIV test than men, while men were more likely to get an HIV test when experiencing physical symptoms.27 Although these cross-sectional studies did not document a decrease in knowledge or perception of HIV risk among males over time, it is possible that among males in the general population, decreasing perception of HIV risk as a major health concern and lower likelihood of being offered or initiating an HIV test contributed to the decrease in men testing in other settings.

Limitations

This study was subject to at least four limitations. First, NHIS data are self-reported and subject to recall bias and potential underreporting of sensitive information, such as HIV testing and use of potentially stigmatizing health-care services (e.g., STD clinics). As testing shifts from targeted testing to routine screening, people may be less likely to recall a previous HIV test because they no longer need to actively request one. The potential for underreporting of previous HIV testing is likely higher in more recent years and could have reduced our ability to detect true increases in testing trends. Second, NHIS excludes active military personnel and those who live outside of households (e.g., people who are incarcerated, in long-term care institutions, or homeless). As such, these populations might be tested at different rates than people in households.

Third, item nonresponse for the HIV test question may vary between groups that are more or less likely to have previously tested for HIV, resulting in biased HIV testing estimates. However, item nonresponse for the HIV test and test setting questions was <5% and 1.6%, respectively, of responders annually.9 Overall, people with item nonresponse for the HIV test question were similar by age, race/ethnicity, and sex to those who reported having never been tested (Unpublished data. NHIS 2003–2010), indicating that our estimates might be minimally higher than if people with item nonresponse for the HIV test question were included in the denominator. However, it would likely not affect trends over time. Finally, test settings were categorized as publicly funded or other based on assumptions regarding the primary funding streams for these venues; as such, they were subject to misclassification bias.

CONCLUSIONS

HIV testing in publicly funded settings increased significantly from 2006 through 2010 among women but not among men since release of CDC's revised recommendations for HIV screening, highlighting the need to focus more efforts on reaching men. HIV testing in publicly funded settings will continue to play an important role in HIV prevention even with increased health insurance coverage through the Affordable Care Act and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force grade A recommendation for HIV screening.28 Not all financial barriers will be eliminated, such as for people living in states that do not expand Medicaid or for people with traditional Medicaid in states that do not cover routine HIV screening. Additionally, some people (e.g., undocumented immigrants) will continue to be uninsured, while others, due to stigma, may not want an HIV test documented in their insurance file. Publicly funded settings should maintain their successful HIV testing practices for women and increase their focus on HIV screening for men to cover existing gaps in services for this population.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen SC, Van Handel MM, Branson BM, Blair JM, Hall HI, Hu X, et al. Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(47):1618–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Bethesda (MD): Department of Health and Human Services (US), National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; 2011. Treating HIV-infected people with antiretrovirals protects partners from infection. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palella FJ, Jr, Deloria-Knoll M, Chmiel JS, Moorman AC, Wood KC, Greenberg AE, et al. Survival benefit of initiating antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons in different CD4+ cell strata. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:620–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–53. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas—2011. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2013;18:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing among adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viall AH, Dooley SW, Branson BM, Duffy N, Mermin J, Cleveland JC, et al. Results of the Expanded HIV Testing Initiative—25 jurisdictions, United States, 2007–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(24):805–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Center for Health Statistics (US) National Health Interview Survey—questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation, 1997–present (survey description documents for 2003–2010) [cited 2014 Feb 13] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_questionnaires.htm.

- 10.Duran D, Beltrami J, Stein R, Voetsch A, Branson B. Persons tested for HIV—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(31):845–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.SAS Institute, Inc. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2012. SAS®: Version 9.3 for Windows. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clegg LX, Hankey BF, Tiwari R, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK. Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat Med. 2009;28:3670–82. doi: 10.1002/sim.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong VT, Dietz PM, Morrow B, D'Angelo DV, Farr SL, Rockhill KM, et al. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 sites, 2000–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62(6):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services (US), CDC; 2011. HIV counseling and testing at CDC-funded sites, United States, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, 2006–2007. Also available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/testing_report_2006_2007.pdf [cited 2015 May 18] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services (US), CDC; 2012. HIV testing at CDC-funded sites, United States, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, 2010. Also available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/testing_cdc_sites_2010.pdf [cited 2015 May 18] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17:1–26. Also available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_hssr_vol_17_no_4.pdf [cited 2015 May 18] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers JJ, Modica C, Dufour MK, Bernstein C, McNamara K. Routine rapid HIV screening in six community health centers serving populations at risk. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1269–74. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1070-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weis KE, Liese AD, Hussey J, Coleman J, Powell P, Gibson JJ, et al. A routine HIV screening program in a South Carolina community health center in an area of low HIV prevalence. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:251–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Revised recommendations for HIV screening of pregnant women. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50(RR-19):59–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (US) Decision memo for screening for the human immunodeficiency virus infection (CAG-00409R) [cited 2015 Sep 18] Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=276.

- 21.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. State Medicaid coverage of routine HIV screening. 2014 [cited 2014 Sep 9] Available from: http://kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/state-medicaid-coverage-of-routine-hiv-screening.

- 22.Mohajer MA, Lyons M, King E, Pratt J, Fichtenbaum CJ. Internal medicine and emergency medicine physicians lack accurate knowledge of current CDC HIV testing recommendations and infrequently offer HIV testing. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2012;11:101–8. doi: 10.1177/1545109711430165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arya M, Zheng MY, Amspoker AB, Kallen MA, Street RL, Viswanath K, et al. In the routine HIV-testing era, primary care physicians in community health centers remain unaware of HIV-testing recommendations. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13:296–9. doi: 10.1177/2325957413517140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson JE, Santelli J, Mugalla C. Changes in HIV-related preventive behavior in the US population: data from national surveys, 1987–2002. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2003;34:195–202. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200310010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors. National HIV prevention inventory—2013 funding survey report. 2013 [cited 2015 Sep 18] Available from: https://www.nastad.org/sites/default/files/NHPI-2013-funding-report-final.pdf.

- 26.Swenson RR, Rizzo CJ, Brown LK, Vanable PA, Carey MP, Valois RF, et al. HIV knowledge and its contribution to sexual health behaviors of low-income African American adolescents. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102:1173–82. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30772-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siegel K, Lekas HM, Olson K, VanDevanter N. Gender, sexual orientation, and adolescent HIV testing: a qualitative analysis. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21:314–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moyer VA. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:51–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]