Abstract

Objective

Public health nurses (PHNs) represent the single largest group of public health practitioners working in U.S. state and local health departments. Despite the important role of PHNs in the delivery and administration of public health services, little research has been conducted on this group and relatively little is known about PHN education, training, and retirement intentions. We describe the findings of a nationally representative survey of PHNs working in state and local health departments by characterizing their educational background and plans for retirement.

Methods

An advisory committee convened by the University of Michigan Center of Excellence in Public Health Workforce Studies developed the Public Health Nurse Workforce Survey and disseminated it in 2012 to 50 U.S. state and 328 local health departments.

Results

The 377 responding state and local health departments reported an estimated 34,521 full-time equivalent registered nurses in their employ, with PHNs or community health nurses as the largest group of workers (63%). Nearly 20% of state health department PHNs and 31% of local health department PHNs were educated at the diploma or associate's degree level. Approximately one-quarter of PHNs were determined to be eligible for retirement by 2016. Professional development and promotion opportunities, competitive benefits and salary, and hiring procedures were among the recruitment and retention issues reported by health departments.

Conclusion

PHNs were reported to have highly variable occupational classifications and educational backgrounds in health departments. Additional training opportunities are needed for PHNs with diploma and associate's degrees. A shortage of PHNs is possible due to retirement eligibility and administrative barriers to recruitment and retention.

Public health nurses (PHNs) represent the single largest group of public health practitioners working in U.S. state health departments (SHDs) and local health departments (LHDs).1 Prior workforce enumeration studies suggest the size of the PHN workforce has remained relatively stable for the last 15 years. A 2000 study estimated nearly 37,000 PHNs (roughly 11% of the state and local public health workforce) working in state and territorial public health agencies.2 A more recent 2012 enumeration using combined 2010 national profile data from the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) and the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) estimated a total of nearly 39,000 PHNs, or almost 15% of the entire workforce,3–5 in SHDs and LHDs. A follow-up 2014 public health workforce enumeration study found 41,000 nurses (approximately 18% of the workforce) in SHDs and LHDs.1 However, none of these studies provided information on educational characteristics of the PHN workforce or addressed factors related to nurse recruitment, retention, or retirement.

PHNs are vital to the delivery of essential public health services for populations, and often possess diverse skills to carry out job tasks related to clinical diagnostics and treatment, epidemiology, statistics, health promotion, disease surveillance, community health assessment, and policy development.6 In addition, PHNs frequently provide direct patient care for vulnerable and underserved populations.7 Workforce supply and worker characteristics, such as educational background, continue to be important considerations when assessing the capacity of the PHN workforce to effectively deliver public health services. On a national level, the government public health workforce is shrinking,8–10 although few studies have determined the types of workers being lost and the reasons for these losses. Partially driven by the lack of systematic data collection to monitor the size and composition of the public health workforce generally,11 and PHNs specifically, concern about a potential PHN shortage12 has prompted a call for further research on the PHN workforce.13 To help address that need, we describe the educational background, and recruitment, retention, and retirement factors of the PHN workforce based on survey responses of SHDs and LHDs.

METHODS

Survey development

Beginning in 2012, a national advisory committee convened by the University of Michigan School of Public Health Center of Excellence in Public Health Workforce Studies developed the Public Health Nurse Workforce Surveys. For this study, PHNs were defined as all licensed registered nurses (RNs) who were employed or contracted by an SHD or LHD. Two surveys were developed to collect PHN workforce data: one for individual RNs and one targeted to health departments, which is the focus of this article.

The Association of Public Health Nurses (APHN) developed a “Count Me In!” marketing campaign to promote awareness and participation in the national online survey prior to its dissemination. APHN distributed the survey link to PHN contacts in all 50 U.S. states, who in turn disseminated the link to a nurse administrator or other appropriate respondent (i.e., the key informant) in an SHD or LHD. Data were extracted from the health department's human resources information. APHN staff followed up with health department contacts throughout the three-month data collection period to encourage completion and offer technical assistance. The survey required approximately one hour to complete, including data gathering time, and included questions about agency RN workforce size, job characteristics and requirements, shortage projections, and recruitment issues, among others.7

Study design and population

The study used a two-stage survey design that included all 50 SHDs in addition to a nationally representative, randomized sample drawn from a listing of 2,565 LHDs from all 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C., provided by NACCHO. To generate the LHD sample, health departments were first stratified by the population size of the LHDs' jurisdictional catchment area: small (<50,000 people), medium (50,000–499,999 people), and large (≥500,000 people).14 A randomized sample of 328 LHDs was then drawn using SAS® PROC SURVEYSELECT.15 The study sample of 328 LHDs was proportionally reflective of both governance structure (e.g., decentralized or centralized as determined by ASTHO4) and jurisdictional category (e.g., county or city) nationally, while LHDs with a large jurisdictional catchment size were oversampled. A single LHD in the sample was removed from the study because the SHD reported its data for it. The final study sample included 50 SHDs and 327 LHDs for a total of 377 health departments. A target response rate of 80% was established for both SHDs (n=40) and LHDs (n=262) in the survey to achieve sufficient power to complete additional statistical analyses in the future. Data were collected in mid- to late-2012 and analyzed in 2013.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed using Microsoft® Excel® and SPSS® version 19.16 Response denominators for individual questions varied throughout the survey. Results were tabulated in aggregate for all responses from health departments from the 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C. Partial survey responses were included if data on workforce size were reported. LHD response totals were calculated using probability of selection weighting. The profile of respondents to the organizational-level survey closely matched the sample profile; therefore, nonresponse weighting adjustments were not needed. Proportional adjustments were made to account for item nonresponse in the LHD data to provide a more accurate national estimate for variables whose data were totaled. SHDs were not weighted and no nonresponse adjustments were made.

RESULTS

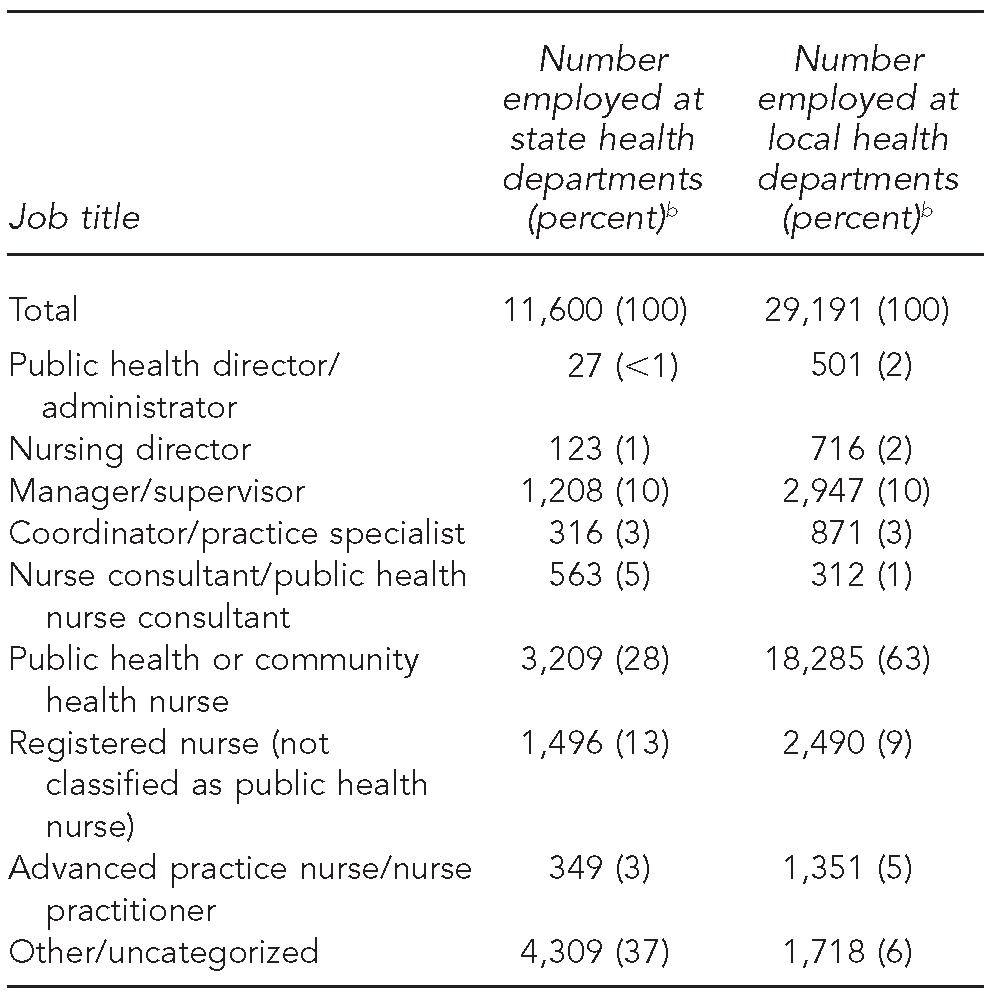

Of 377 health departments that received the survey, a total of 310 (82%) responded, including 45 SHDs and 265 LHDs, achieving response rates of 90% and 81%, respectively. The 45 responding SHDs reported employing a total of 12,063 RNs, the full-time equivalent (FTE) of 11,600 RNs (Table 1), of which 260 (2%) FTEs were contracted staff. Approximately 6,270 (54%) FTE RNs employed/contracted by SHDs worked in an LHD setting, leaving 5,330 FTE RNs employed in an SHD setting. The 265 responding LHDs reported 4,785 RN workers, equivalent to 4,212 FTE RNs. Weighting LHD responses resulted in an estimate of approximately 29,191 FTE RNs employed in LHDs nationally (Table 1), 1,979 (7%) of which were contract employees.

Table 1.

Registered nurses employed at 45 respondent U.S. state and 265 local health departments, by job title, Public Health Nurse Workforce Survey, 2012a

Data were obtained from the organizational-level survey. Job titles were not provided for 3,345 state workers. Local health department estimates were based on proportional extrapolations of 4,077 registered nurses.

bPercentages do not sum to 100 due to rounding.

The 11,600 FTE RNs in the responding SHDs and the estimated 29,191 FTE RNs in LHDs together yielded an approximate national PHN workforce in SHDs and LHDs of 40,791 RNs. However, it is likely that the LHD total included the 6,270 SHD RNs who were actually working in LHDs. To adjust for this possible redundancy in reporting, the 6,270 SHD RNs were removed from the total number of FTE RNs in SHDs and LHDs responding to this survey, leaving an estimated workforce size of 34,521 FTE RNs.

Workforce size by occupational classification

Forty-three SHDs provided RN job classification data. Based on proportional extrapolations of 11,600 RNs in SHDs, 28% of RNs were PHNs or community health nurses, 13% were RNs, and 10% were managers/supervisors. Other job titles included nurse consultant/public health nurse consultant (5%), coordinator/practice specialist (3%), and advanced practice nurse/nurse practitioner (3%). Approximately 37% of RNs were either classified as other (n=964) or were uncategorized (n=3,345) (Table 1). Surveyor and inspector/regulator were among the most common “other” job categories for SHD RNs.

Based on proportional extrapolations of 4,077 RNs, 63% of LHD RNs were PHNs or community health nurses, 10% were managers/supervisors, and 9% were RNs. Other job titles included advanced practice nurses (5%), coordinators (3%), nursing directors (2%), public health directors (2%), and nurse consultants (1%). Six percent did not report a job title (Table 1).

Educational background

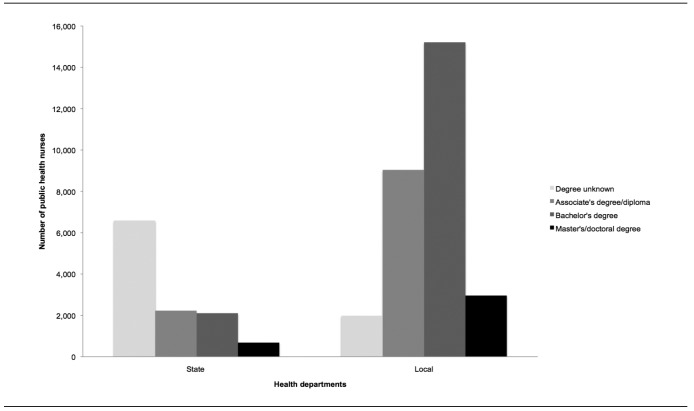

The highest level of nursing degree was reported for 5,011 of the 11,600 RNs employed or contracted by SHDs. Approximately 2,227 (19%) RNs were educated at the associate's degree or diploma level, 2,105 (18%) held a bachelor's degree in nursing, and 679 (6%) held a master's or doctoral degree in nursing. Degree level was not reported by the health department for 6,589 (57%) RNs (Figure).

Figure.

Highest nursing degree obtained by public health nurses employed or contracted by state and local health departments, United States, 2012a

aThe sample size for public health nurses was 11,600 for state health departments and 29,161 for local health departments. These numbers included nurses who may have been represented in both local and state health department counts (e.g., nurses employed by the state health department working in a local unit).

A total of 15,213 (52%) held a bachelor's degree in nursing, 9,039 (31%) held an associate's degree or diploma, and 2,957 (10%) held a master's or doctoral degree in nursing. The degree level was not reported for 1,982 (7%) LHD RNs (Figure).

Workforce recruitment, retention, and retirement

Retirement and shortage projections.

Only 14 SHDs had estimated the number of RNs who would be eligible for retirement from fiscal years 2012 to 2016 at the time of the survey, 12 of which provided analyzable retirement projection figures for the 1,901 RNs employed or contracted by those agencies. Of the 1,901 RNs in the states' workforce, approximately 509 (27%) were expected to be retirement-eligible by 2016, with a range of 80–135 (4%–7%) RNs reaching retirement eligibility each year. One hundred-forty LHDs in the survey sample reported having estimated retirement eligibility for their RNs from 2012 to 2016. Similar to the SHD RN workforce, 778 of 3,089 (25%) nurses in those jurisdictions was expected to be retirement eligible during those five years, with 133 (4%) eligible in 2012, 104 (3%) eligible in 2013, 129 (4%) eligible in 2014, 158 (5%) eligible in 2015, and 254 (8%) eligible in 2016.

Twenty-seven SHDs reported anticipating a shortage of RNs to meet their health department's service needs by 2017. Twenty-one of the 27 SHDs reported worker retirements and noncompetitive wages as factors contributing to a shortage of RNs, 19 anticipated budget reductions as a factor, seven reported low job satisfaction as a possible shortage factor, and five reported other factors including lack of willingness to relocate, replacement of nurses by paraprofessionals, uncertainty of support of public health programs, an inadequate benefits package, and an overall labor shortage of RNs. Among LHDs, 85 jurisdictions indicated anticipating a shortage of RNs by 2017. Approximately 79% of LHDs reported that noncompetitive wages would be a factor contributing to a shortage of RNs, 74% anticipated budget reductions as a factor, 51% reported worker retirements resulting in an RN shortage, 14% reported low job satisfaction as a possible shortage factor, and 12% reported other factors including educational requirements being unmet, local competition for RNs, lack of qualified applicants for open positions, and job location.

Recruitment and retention factors.

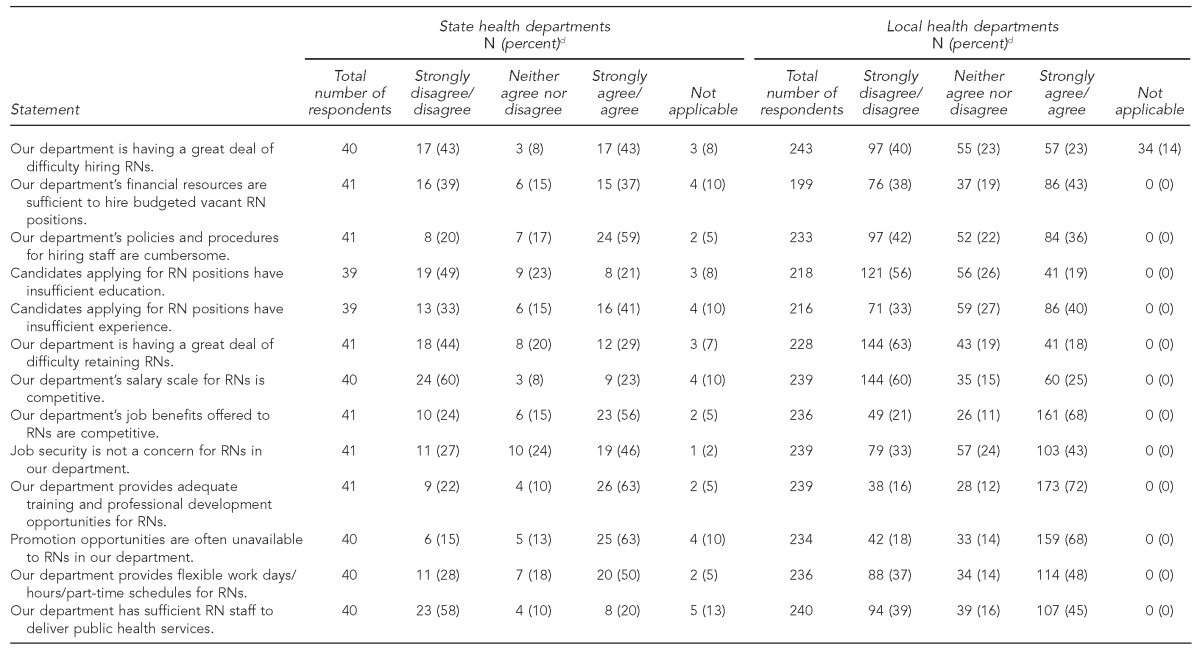

At least half of the 41 responding states agreed or strongly agreed with the following statements related to hiring and/or retaining RNs: department provides adequate training and professional development opportunities for RNs, promotion opportunities are often unavailable to RNs, department's policies and procedures for hiring staff are cumbersome, department's job benefits are competitive, and department provides flexible schedules. Recruitment and retention factors of most concern for SHDs included job security for RNs, difficulty hiring RNs, insufficient experience of candidates applying for RN positions, and lack of departmental financial resources to hire budgeted vacant RN positions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Agreement level of statea and localb health departments responding to a survey on recruitment and retention factors for public health nurses, United States, 2012c

All 50 state health departments were surveyed; 45 states responded.

A nationally representative sample of 328 local health departments was drawn from a listing of 2,565 local health departments from all 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C., provided by the National Association of County and City Health Officials. Final sample included 327 local health departments; 265 responded.

Surveys were distributed to nurse manager contacts and were likely completed by multiple staff members within the health department, including human resources personnel or administrators.

dNot all percentages sum to 100 due to rounding.

RN = registered nurse

In the LHD sample, more than half of responding health departments agreed or strongly agreed with the following statements about RNs in their agencies: department provides adequate training and professional development opportunities, job benefits offered are competitive, and promotion opportunities are often unavailable. Recruitment and retention factors of most concern to LHDs included the ability to provide flexible work schedules, having sufficient RN staff to deliver public health services, job security for RNs, and lack of departmental financial resources to hire budgeted vacant RN positions (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our findings provide data supported by the Public Health Systems and Services Research Agenda, which emphasizes the need for more research on educational background, supply and demand, and recruitment and retention factors of the public health workforce.17 The study showed that PHNs occupy many different positions in health departments and have highly varied job titles, which is consistent with PHNs fulfilling assorted key roles in SHDs and LHDs dispersed across administrative/managerial, programmatic, and clinical areas, or a combination of these areas.

The study findings revealed a significant need to strengthen the education and training of PHNs. Although the American Nurses Association Scope and Standards of Practice18 recommends education at the bachelor of science level in nursing for PHNs, nearly 20% of SHD and 31% of LHD PHN workforces had only a diploma or associate's degree. PHNs have historically filled a variety of roles in health departments; however, our findings indicated that a large percentage of this workforce was unlikely to have had the formal public health training or educational background needed to develop the skills for these roles, which could be a significant PHN workforce development issue to be addressed. This finding is especially important because health-care reform measures may result in reduced clinical service provision in most health departments, thereby lessening the role of and need for clinicians such as doctors and nurses, and increasing the demand for public health-educated staff in health departments with a greater understanding of population-based prevention and programmatic interventions. Additionally, the ever-increasing number of accredited schools and programs of public health offering a master of public health degree are producing substantially more graduates with specialty training who are moving into the public health job market.19 These professionalization trends in the public health workforce may create a push for higher levels of formal public health training and education among PHNs.

Findings from this study indicated that many health departments, particularly those at the state level, did not have retirement projections for RNs available to report. It is unknown whether these health departments elected not to report this information or simply lacked the requisite data to report, which would clearly be a significant impediment to accurately projecting future workforce needs. The health department respondents that were able to provide this information estimated more than one-quarter of the PHN workforce as eligible for retirement by 2016, which is higher than the percentage estimated in similar studies of epidemiologists20 and public health laboratory workers,21 but is consistent with previous ASTHO projections of state public health worker retirement eligibility generally.22

Given the central role PHNs play in public health department operations, particular attention should be paid to the recruitment and retention factors identified by health departments, as replenishing the PHN workforce pipeline and replacing workers lost to retirement will be a critical challenge going forward. Most respondents indicated that provision of training and professional development opportunities was a recruitment and retention strength of their health department; however, many respondents also noted barriers, such as a lack of promotion opportunities for RNs, job insecurity, lack of budget to hire vacant RN positions, and inability to offer a competitive salary to RNs. These administrative issues deserve further exploration to avoid a potential PHN workforce shortage, which is a growing national concern.12 Job insecurity was another barrier reported by health departments, a finding that is supported by the program cuts and job losses reported by SHDs and LHDs to ASTHO and NACCHO as a result of the economic downturn.23,24

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. First, the results provided a weighted estimate of the number of RNs in LHDs nationally as a result of sampling; however, all SHDs were included in the survey and five states did not respond to the survey, resulting in missing data. For reference purposes, three of the five nonresponding states reported an approximate total of 1,121 PHNs in the 2010 ASTHO Profile Survey,10 although the definition of PHN used by ASTHO was slightly different than the definition used in our study. The remaining two states did not report their number of PHNs. Additionally, some respondents, SHDs in particular, were unable to provide data for all nurses they employed or contracted with, especially those working in state-run hospitals. It is possible that some LHD RN data were dropped from the study when adjustments were made for duplicate counting, although we believe this omission to be minimal.

In addition, the job of the person who completed the survey likely differed by health department; nurse managers, human resources personnel, and administrators all completing the survey is a common methodology for health department workforce surveys. This difference could have affected the validity of the results if respondents completed questions differently. Respondents based their agency's FTE estimate on the number of personnel within certain job titles commonly held by RNs. It is possible that RNs in other job titles, such as administrative or other nonclinical job titles, were omitted from this survey. Finally, SHDs in particular had high levels of nonresponse for the educational background survey questions and were unable to categorize more than one-third of their RN workforce into a specific job classification.

CONCLUSION

The PHN workforce in SHDs and LHDs comprises a diverse group of RNs in terms of occupational classification and educational background. A substantial percentage of this workforce may be eligible for retirement by 2016, creating a potential shortage of this critical component of the government public health workforce. Strategies should be developed to provide additional training opportunities for the large percentage of nurses educated at the diploma and associate's degree level and to address administrative barriers to recruiting and retaining RNs into public health practice to ensure effective delivery of population health services.

Footnotes

The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board deemed this study as exempt from continuing review.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beck AJ, Boulton ML, Coronado F. Public health workforce enumeration, 2014. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(5 Suppl 3):S306–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gebbie K, Merrill J, Hwang I, Gebbie EN, Gupta M. The public health workforce in the year 2000. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9:79–86. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.University of Michigan Center of Excellence in Public Health Workforce Studies. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan; 2013. Public health workforce enumeration, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Arlington (VA): ASTHO; 2011. ASTHO profile of state public health, volume two. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Association of County and City Health Officials. Washington: NACCHO; 2011. 2010 national profile of local health departments. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell SL, Fowles ER, Weber BJ. Organizational structure and job satisfaction in public health nursing. Public Health Nurs. 2004;21:564–71. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.21609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulton ML, Beck AJ. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan Center of Excellence in Public Health Workforce Studies; 2013. Enumeration and characterization of the public health nurse workforce: findings of the 2012 Public Health Nurse Workforce Surveys. Also available from: http://www.sph.umich.edu/cephw/docs/nurse%20 workforce-RWJ%20report.pdf [cited 2015 Sep 3] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Arlington (VA): ASTHO; 2014. ASTHO profile of state public health, volume three. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Association of County and City Health Officials. Washington: NACCHO; 2013. Local health department job losses and program cuts: findings from the 2013 profile study. Also available from: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/lhdbudget/upload/survey-findings-brief-8-13-13-3.pdf [cited 2015 Sep 3] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck AJ, Boulton ML. Trends and characteristics of the state and local public health workforce, 2010–2013. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 2):S303–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boulton ML, Beck AJ, Coronado F, Merrill JA, Friedman CP, Stamas GD, et al. Public health workforce taxonomy. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(5 Suppl 3):S314–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reilly JE, Fargen J, Walker-Daniels KK. A public health nursing shortage. Am J Nurs. 2011;111:11. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000399292.51773.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Association of Community Health Nursing Educators (ACHNE) Research Committee. Research priorities for public health nursing. Public Health Nurs. 2010;27:94–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Association of County and City Health Officials. Washington: NACCHO; 2014. 2013 national profile of local health departments. Also available from: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/profile/upload/2013-national-profile-of-local-health-departments-report.pdf [cited 2015 Sep 3] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SAS Institute, Inc. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2012. SAS®: Version 9.3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.IBM Corp. Armonk (NY): IBM Corp.; 2012. SPSS®: Version 19 for Macintosh. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Consortium from Altarum Institute; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; National Coordinating Center for Public Health Services and Systems Research. A national research agenda for public health services and systems. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5 Suppl 1):S72–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Nurses Association. 2nd ed. Silver Spring (MD): American Nurses Association; 2013. Public health nursing: scope and standards of practice. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulton ML, Baker EL, Beck AJ. The public health workforce. In: Erwin PC, Brownson RC, editors. Scutchfield and Keck's principles of public health practice. 4th ed. Clifton Park (NY): Cengage Learning; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck AJ, Boulton ML, Lemmings J, Clayton JL. Challenges to recruitment and retention of the state health department epidemiology workforce. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boulton ML, Beck AJ, DeBoy JM, Kim DH. National assessment of capacity in public health, environmental, and agricultural laboratories—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(9):161–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Arlington (VA): ASTHO; 2008. 2007 State Public Health Workforce Survey results. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Arlington (VA): ASTHO; 2012. Budget cuts continue to affect the health of Americans: update March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Association of County and City Health Officials. Washington: NACCHO; 2010. Local health department job losses and program cuts: findings from January/February 2010 survey. Also available from: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/lhdbudget/upload/job-losses-and-program-cuts-5-10.pdf [cited 2015 Sep 3] [Google Scholar]