Abstract

We have been focused on identifying a structurally different next generation inhibitor to MK-5172 (our Ns3/4a protease inhibitor currently under regulatory review), which would achieve superior pangenotypic activity with acceptable safety and pharmacokinetic profile. These efforts have led to the discovery of a novel class of HCV NS3/4a protease inhibitors containing a unique spirocyclic-proline structural motif. The design strategy involved a molecular-modeling based approach, and the optimization efforts on the series to obtain pan-genotypic coverage with good exposures on oral dosing. One of the key elements in this effort was the spirocyclization of the P2 quinoline group, which rigidified and constrained the binding conformation to provide a novel core. A second focus of the team was also to improve the activity against genotype 3a and the key mutant variants of genotype 1b. The rational application of structural chemistry with molecular modeling guided the design and optimization of the structure–activity relationships have resulted in the identification of the clinical candidate MK-8831 with excellent pan-genotypic activity and safety profile.

Keywords: Antiviral, HCV, NS3/4a, genotype 3a, pan-genotypic, macrocycle, MK-5172, MK-8831

In the 25 years that have passed since the first report of cloning of hepatitis C virus (HCV), the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus has undergone dramatic changes.1 Approximately 170–200 million people worldwide are chronically infected with HCV with majority infected by genotype 1 (∼70% of all cases of HCV in United States), 2, and 3.2 Among the six major genotypes (gt) 1–6 that have so far been identified, gt1 is the most prevalent worldwide comprising 83.4 million cases (46.2% of all HCV cases) and gt3 the next most prevalent globally (54.3 million, 30.1%). For several years the standard of care was pegylated interferon plus rivabarin, which had a cure rate of only ∼45% for genotype (gt) 1 affected patients with a treatment period of 24–48 weeks and associated with difficult side effects.3 The first approval of direct-acting antiviral agents (boceprevir and telaprevir) was considered a major milestone in the field as it significantly improved the sustained virological response (SVR) up to 75% for naïve HCV genotype 1 patients and shortened the treatment time.4,5 Recent FDA approval of Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi; HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor) and other protease inhibitors have shown promise to further improve the cure rates, tolerability, and shorten treatment for HCV patients.6−8 At Merck, we have recently reported impressive cure rates with MK-5172 (NS3/4a protease inhibitor) in combination with MK-8742 (NS5A inhibitor), resulting in “breakthrough” designation from FDA and is currently under regulatory review.9 Recent focus across the pharmaceutical industry has been to combine compounds from different classes of HCV direct acting antivirals (DAAs) that would offer an all-oral interferon free treatment option. In this context there is a continuing need for potent pan-genotypic NS3/4a protease inhibitors with high barrier to resistance against gt variants.

We have previously reported the discovery of MK-5172 (P2–P4 HCV macrocyclic protease inhibitor) and newer pan-genotypic quinoline analogues as protease inhibitors.10−12 Several P1–P3 HCV protease inhibitors, e.g., simprevir, danoprevir, asunaprevir, and faldaprevir, have also been reported by others.7,13−15 While earlier protease inhibitors are highly effective for gt1 patients, they have limited efficacy against gt3a and multiple resistant variants for gt1b. Hence, we were interested to follow-up MK-5172 with a compound that would be structurally different and further improve potency specifically against genotype 1 (gt1) resistant variants and genotype 3 (gt3) but also provide robust pan-genotypic activity.

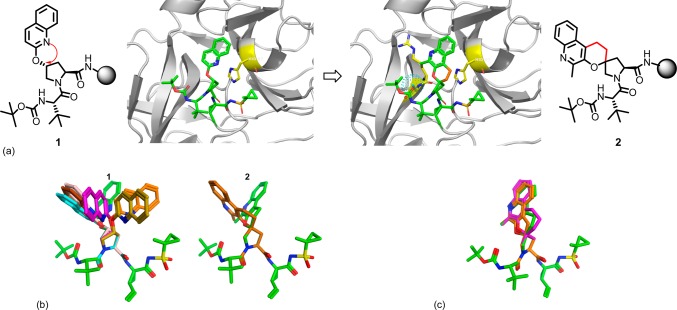

In our efforts leading to the back-up of MK-5172, we decided to employ a molecular modeling strategy and focus on novel variants of P2 quinolines. We have previously reported that modifying the P2 quinoline region could improve gt3a activity.11 We were interested to see if we could impart structural rigidity to these optimized P2 groups and possibly identify a novel alternative core with significant potency improvements. Our efforts started with the previously reported acyclic P1–P3 compound 1 with a rational modeling approach and a focus on imparting structural modifications focused on the P2 quinoline region to improve potency specifically on gt3a and gt1.16 After carefully looking at several constrained models of P2, we hypothesized that a spirocyclization of the quinoline moiety onto the proline could make favorable van der Waals contacts with histidine (H57) an invariant catalytic residue, which may result in an improved mutant profile. Spirocyclization would also impart greater conformational rigidity to the molecule and may provide an advantage with reduced entropic cost of binding by biasing it toward the bioactive conformation (Figure 1a). We chose the 2-methyl quinolone 2 for spirocylization as modeling indicated that the methyl group could have favorable hydrophobic interactions with A156 in the enzyme.

Figure 1.

(a) Comparison of the models of acyclic and spirocyclized P2-proline inhibitors and their interactions with H57. (b) Conformational analysis of the P2 side chains of acyclic compound 1 and spiro compound 2. The bound conformation is colored green. Only low energy conformers (dE < 2 kcal/mol) are shown. (c) Overlay of 5–7-membered spiro-cyclic rings with the 6-membered ring in green.

To test our hypothesis we performed a conformational analysis and molecular dynamics simulations of the open chain and the spirocyclized P2. It was nice to see that though multiple conformers exist below 2 kcal for the acyclic version 1, only two low energy conformers are available for the spiro compound 2 (Figure 1b). It is noteworthy that conformational analysis of the P2 groups, while constraining the rest of the inhibitor in the bound conformation, indicates that the bound conformation of P2 is essentially the lowest energy conformations for both inhibitors 1 and 2. In addition, different ring sizes 5–7 were explored using molecular modeling, and the 6-membered ring was the apparent choice to mimic the parent acyclic P2 (Figure 1c).

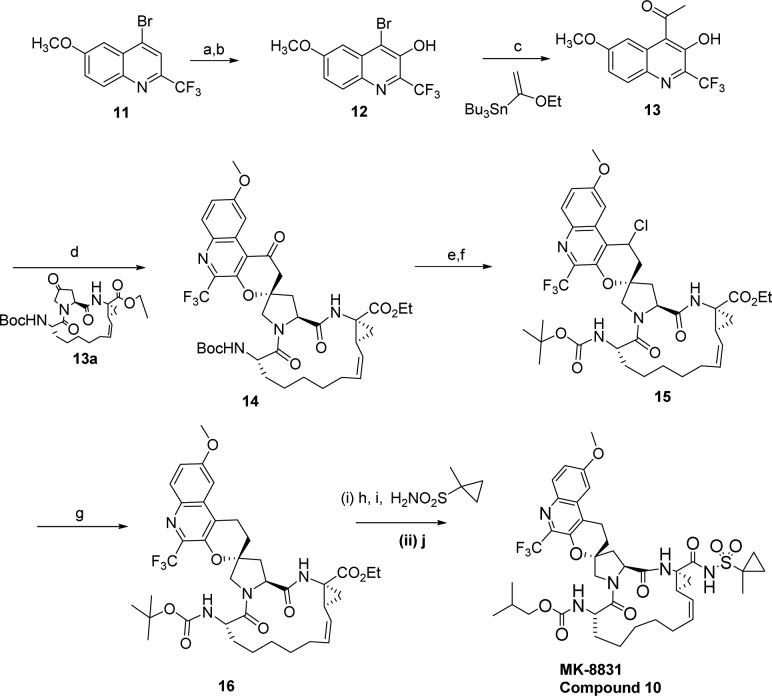

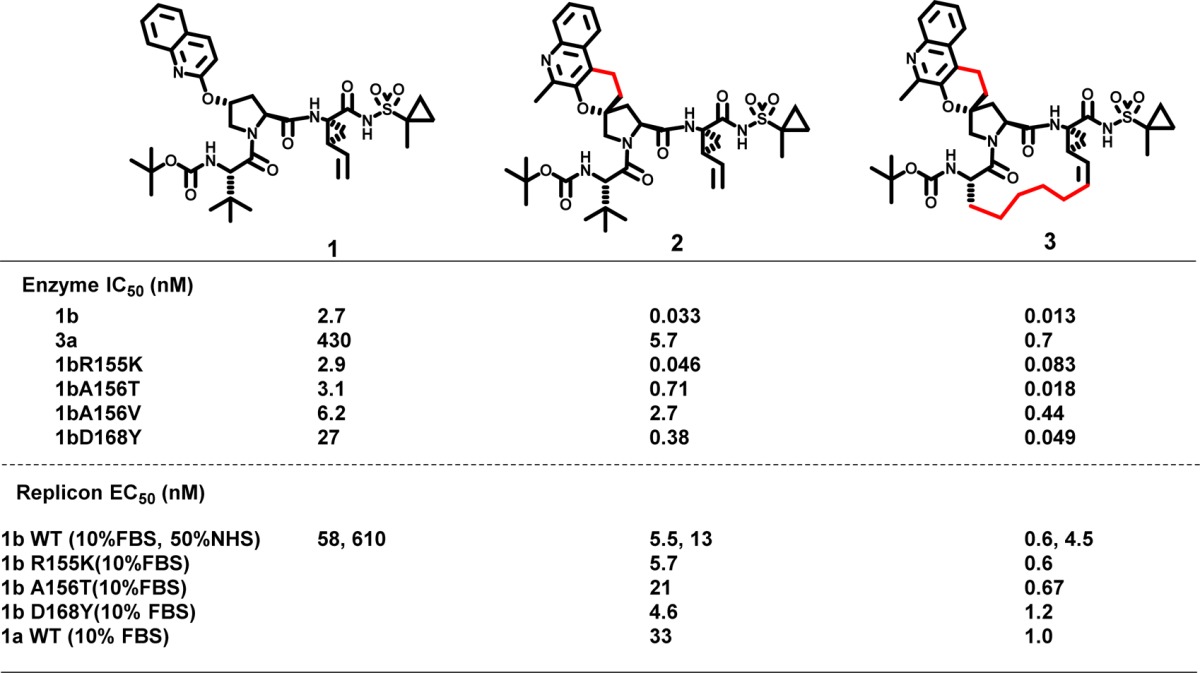

The enzyme and replicon data of the linear compound 1 and spiro 2 are compared in Table 1. As can be seen from the data, the spiro-cyclization of the P2 groups to proline improved the potency of genotype 1b, 3a by ∼80-fold, and the overall potency against key 1b mutants. With the proof of concept that improved conformational rigidity results in improved pan-genotypic profile of 2, we decided to see if we can further improve the potency of the spirocyclic proline analogue by forming a P1–P3 macrocycle. As described before, several P1–P3 macrocycles have been reported to have improved potency and pharmacokinetic properties, and we reasoned that a macrocycle of 2 would further boost pan-genotypic potency of this spiro-proline hit.13−15 With this in mind, 3 was synthesized and as can be seen from the data in Table 1, compound 3 displayed excellent potency profile with picomolar activity against 1b and 8-fold improvement in 3a in the enzyme panel. Compound 3 also showed significantly improved potency profile against resistant associated variants (RAV) of 1b like R155K, A156T, A156V, and D168Y. The replicon assay also showed similar potency boost across the 1b wild type and the associated RAVs.

Table 1. Enzyme and Replicon Data Showing Potency Improvements for the Spiro-Prolines 2 and 3 When Compared to Acyclic Compound 1 for gt1b, gt3a, and gt1 Resistant Variants.

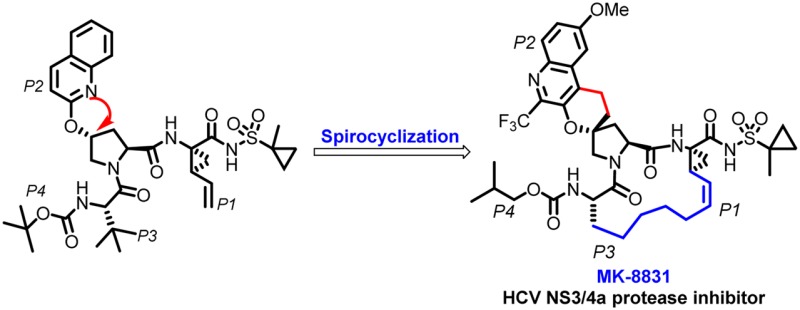

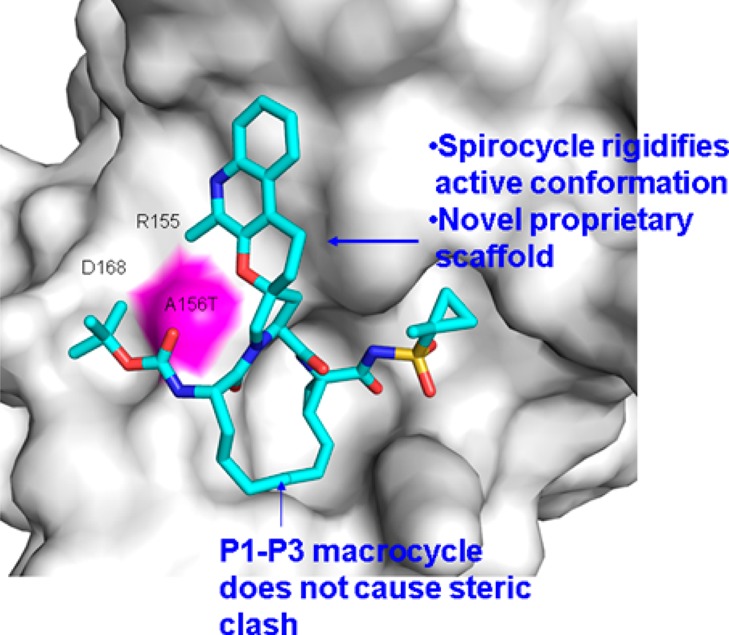

Differences in genotype 1–3 are seen close to P1–P4 region and hence most of the previously reported P2–P4 macrocycle inhibitors interact with A156 and its mutation to threonine results in resistance. By moving to a spiro-macrocycle, which goes via P1–P3, we were able to improve potency against A156T and also genotype 3a as shown in Figure 2 of the compound 3 in the protease binding site. It was particularly gratifying to see that with rational structure-based drug design, the combination of spiro-ring formation and macrocyclization had resulted in a compound with excellent pan-genotypic activity. Having achieved excellent in vitro profile with 3, our next goal was to assess the pharmacokinetic properties of this compound. Unfortunately, we found that compound 3 gave very poor exposures after oral administration. At 5 mpk, the compound showed poor AUC(0–24 h) of 0.14 μM·h, short t1/2 = 0.9 h, and poor bioavailability of 4%. As HCV targets the liver, the concentration of the drug in liver was always measured and served as an important criterion for advancement. However, this compound had negligible liver levels at 24 h.

Figure 2.

Overlay of compound 3 in the binding site of the protease.

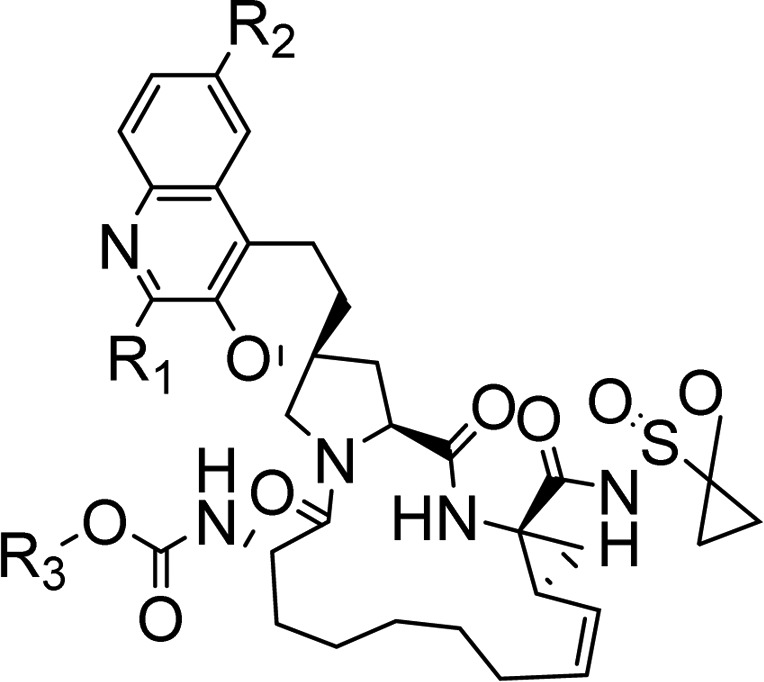

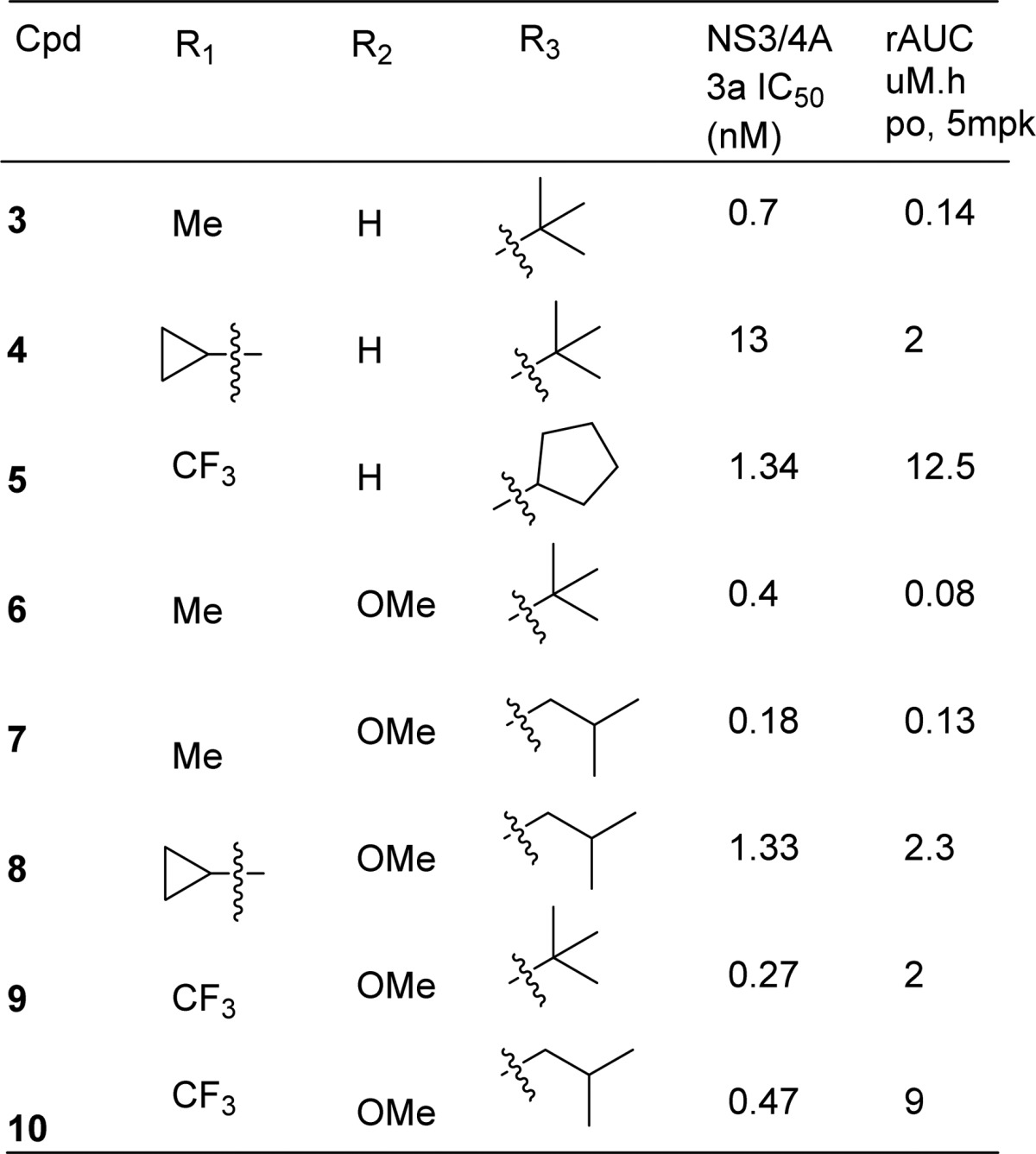

Our efforts to balance pharmacokinetic profile and potency of compound 3 were mostly focused on the P2 aromatic region and P4 carbamates as some of the previous reported structure–activity relationships (SARs) from us and our peers had already shown the methyl cyclopropyl group (P1′) to be an optimal group for binding.14 The P1–P3 macrocycle was also designed based on modeling and had the optimized chain length to avoid any steric interactions related loss in potency.17 For SAR purposes, we mainly focused on balancing gt3a potency with rat AUC as activity against this genotype was highly sensitive to changes to the P2 or P4 regions. Though we did make significant functional group modifications, Table 2 below highlights only the compounds that were the key breakthroughs as we tried to optimize the properties to identify a clinical candidate. We reasoned that the methyl group in the quinolone could be a liability to oxidative metabolism and when the methyl group in 3 was converted to cyclopropyl 4 we were pleased to see the first hint of oral exposure, but it came with reduced gt3a activity. When we introduced a trifluoromethyl group in the quinoline 5 and changed the t-butyl to cyclopentyl carbamate in P4, we had the first example that had a good balance of oral exposures and gt3 activity. The second key functionality that made a big improvement to potency was a methoxy group on quinoline as can be seen in compound 6 but again resulted in a loss in plasma exposure. We also found the isobutyl carbamate to be a better group at improving rat AUC while maintaining good gt3a potency. By combining the three key functionalities that we had identified [(i) trifluoromethyl, (ii) methoxy group on quinoline, and (iii) isobutyl carbamate] we discovered compound 10, which had a favorable balance of potency and plasma exposures in both rat and dog and was later identified as the preclinical candidate MK-8831 (Table 2).

Table 2. SAR of P2 and P4 Groups: Comparison with gt3a Potency and Rat AUC.

The synthesis of compound 10 is shown in Scheme 1. Commercially available bromide 11 was converted to a borate, which was then treated with mCPBA mediated conditions to generate the phenol 12. Compound 12 was then treated under tin mediated conditions to obtain the important precursor ketone 13. The ketone was then cyclized with the previously reported macrocyclic prolinone 13a under highly optimized conditions, employing benzoic acid and pyrrolidine.18 While initial conditions gave very poor yields, the optimized methods gave 14 in >65% yield and high levels of diastereoselectivity (dr = 99:1). The ketone of compound 15 was converted to chloride under standard conditions and reduced under a novel nickel boride mediated radical conditions to obtain compound 16. This was a key reaction as other attempts to obtain 16 with hydrogenation or reductive conditions always led to the reduction of the double bond in the macrocycle. The sequence to compound 10 then involved hydrolysis of the ester 16 to acid and coupling with cyclopropyl-methyl sulfonamide followed by deprotection of the Boc group and treatment with isopropyl chloroformate to obtain compound 10 (MK-8831).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of MK-8831.

Reagents and conditions: (a) LDA, B(OCH3)3, THF, −78 °C; (b) mCPBA, NaHCO3, CH3CN; (c) Pd(PPh3)4, 1,4-dioxane, 120 °C; (d) compound 2, pyrrolidine, benzoic acid, 55 °C; (e) NaBH4 (f) MsCl, Et3N; (g) NaBH4, NiCl2·6H2O, (h) LiOH.H2O; (i) cyclopropylmethyl sulfonamide, CDI, DBU; (j) (i) 4 N HCl, (ii) i-BuOCOCl, Et3N.

The activities against various genotypes and the gt1 resistant variants comparing MK-8831 with our clinical compound MK-5172 are shown in Table 3. As can be seen MK-8831 had excellent activity in enzyme and replicon assays and had pan coverage of the prominent resistant genotypes and when compared with our best-in-class protease inhibitor MK-5172, MK-8831 showed significant improvements in potencies for gt1b RAVs like A156T and D168Y. Most importantly in the replicon assays shown in Table 3, MK-8831 showed >4-fold improvement over genotype 3a in comparison to MK-5172.

Table 3. Comparing MK-8831 and MK-5172 Potency (IC50, nM) Across an HCV NS3/4A Enzyme and Replicon Genotype Panel.

| assay | genotype (GT) | MK-8831 | MK-5172 |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCV NS3/4a enzyme assay IC50 (nM) | 1a | 0.009 | 0.007 |

| 1b | 0.004 | 0.004 | |

| 1b R155K | 0.010 | 0.021 | |

| 1b A156T | 0.483 | 3.917 | |

| 1b A156V | 2.760 | 5.511 | |

| 1b D168Y | 0.023 | 0.105 | |

| 3a | 0.413 | 0.690 | |

| HCV NS3/4a replicon assay EC50 (nM) | 1a | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| 1b | 0.8 | 0.3 | |

| 2a | 0.9 | 1.2 | |

| 2b | 3.4 | 5.0 | |

| 3a | 1.7 | 7.2 |

MK-8831 showed good pharmacokinetic profile with oral bioavailability in both rat and dog of 31 and 17%, respectively.19 It was highly protein bound in both species, but the high dose PK showed good margin for us to do safety studies. For human dose predictions we mainly wanted to obtain good coverage for gt1 and 3a. For this purpose we assumed a worst case scenario of 100% serum bound EC90 values as our criteria for a projected human Ctrough. We saw that in 100% NHS (normal human serum) the EC90 values for MK-8831 ranged from 60 to 90 nM (gt1a = 68, 1b = 20, 2a = 60, and 3a = 90). We decided to aim for a human dose that would match the serum adjusted EC90 values at Ctrough (90 nM) and Cmax, which would be ten times that at 900 nM. Based on an allometric scaling mainly using dog clearance and Vd we made a preliminary human PK prediction (hupred: CL= 0.2 mL/min/kg, Vd = 0.1 L/kg, Foral = 15%, t1/2 = 5 h) for a projected efficacy Cmax of 900 nM. Our human dose projections show that a clinical dose of ∼35–100 mg (MRT ≈ 7 h) could yield a target plasma trough of 90 nM. Moving on to safety, MK-8831 had excellent off-target profile. It was clean against the Cyp enzymes (3A4, 2C9, 2D6 up to 50 μM and 2D8 up to 20 μM) and did not show any negative results in mutagenicity studies and in the AMES assays. Compound 10 showed a clean profile in a reproductive toxicity assay up to 300 μM and also in the micronucleus induction assay. We also performed a standard rat/dog telemetry study and found that it was clean in rats and dogs up to 40 mpk with 35× and 366× exposure multiples (EM). In conscious telemetered dogs there were no effects on heart rate, blood pressure, ECG parameters, respiratory function, or body temperature. The three day safety studies performed in rats for MK-8831 achieved excellent exposures at 400 mkd (mg/kg/day) with no safety issues with liver concentration at 134 μM (149× EM).

In summary, based on rational computational modeling and structure-guided SAR designs, we were able to discover a novel spiro-proline scaffold, which was then optimized to obtain MK-8831 with excellent pangenotypic profile and good coverage over the highly resistant 1b variants like A156T, A156V, R155K, and D168Y as well as gt3a. Based on good pharmacokinetic profile and excellent safety, MK-8831 was selected as our preclinical candidate and entered Phase 1 studies. Further clinical data, process development and other SAR studies on MK-8831 will be disclosed in the near future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ann Weber, Dr. Joseph Vacca, and Dr. Chris Hill for their support of this program. We also thank Dr. Alexei Buevich for NMR support.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- SVR

sustained virological response

- DAA

direct acting antivirals

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- gt

genotype

- AUC

area under the curve

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00425.

Synthetic experimental details including 1H NMR and mass spectral data for selected compounds, description of primary biological assays, molecular modeling protocols, and PK data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Choo Q. L.; Kuo G.; Weiner A. J.; Overby L. R.; Bradley D. W.; Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science 1989, 244 (4902), 359–362. 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong G. L.; Wasley A.; Simard E. P.; McQuillan G. M.; Kuhnert W. L.; Alter M. J. The Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 705–714. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghany M. G.; Strader D. B.; Thomas D. L.; Seeff L. B. Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment of Hepatitis C: An Update. Hepatology 2009, 49, 1335–1374. 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poordad F.; McCone J. Jr.; Bacon B. R.; Bruno S.; Manns M. P.; Sulkowski M. S.; Jacobson I. M.; Reddy K. R.; Goodman Z. D.; Boparai N.; DiNubile M. J.; Sniukiene V.; Brass C. A.; Albrecht J. K.; Bronowicki J. P. SPRINT-2 Investigators. Boceprevir for Untreated Chronic HCV Genotype 1 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1195–1206. 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson I. M.; McHutchison J. G.; Dusheiko G.; Di Bisceglie A. M.; Reddy K. R.; Bzowej N. H.; Marcellin P.; Muir A. J.; Ferenci P.; Flisiak R.; George J.; Rizzetto M.; Shouval D.; Sola R.; Terg R. A.; Yoshida E. M.; Adda N.; Bengtsson L.; Sankoh A. J.; Kieffer T. L.; George S.; Kauffman R. S.; Zeuzem S. ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for Previously Untreated Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2405–2416. 10.1056/NEJMoa1012912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid T.; Savini C.; Seyedkazemi S. Sofosbuvir, a significant paradigm change in HCV treatment. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2015, 1, 27–35. 10.14218/JCTH.2014.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist Å.; Samuelsson B.; Johansson P. O.; Cummings M. D.; Lenz O.; Raboisson P.; Simmen K.; Vendeville S.; de Kock H.; Nilsson M.; Horvath A.; Kalmeijer R.; de la Rosa G.; Beumont-Mauviel M. Discovery and development of simeprevir (TMC435), a HCV NS3/4a protease inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1673–1693. 10.1021/jm401507s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks E. D. Ombitasvir/Paritaprevir/Ritonavir Plus Dasabuvir: A review in chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. Drugs 2015, 75, 1027–1038. 10.1007/s40265-015-0412-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawitz E.; Gane E.; Pearlman B.; Tam E.; Ghesquiere W.; Guyader D.; Alric L.; Bronowicki J.-P.; Lester L.; Sievert W.; Ghalib R.; Balart L.; Sund F.; Lagging M.; Dutko F.; Shaugnessy M.; Hwang P.; Howe A.; Wahl J.; Robutson M.; Barr E.; Haber B. Efficacy and safety of 12 weeks versus 18 weeks of treatment with grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK-8742) with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection in previously untreated patients with cirrhosis and patients with previous null response with or without cirrhosis (C-WORTHY): a randomized, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet 2015, 385 (9973), 1087–1097. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61795-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summa V.; Ludmerer S. W.; McCauley J. A.; Fandozzi C.; Burlein C.; Claudio G.; Coleman P. J.; Dimuzio J. M.; Ferrara M.; DiFilippo M.; Gates A. T.; Graham D. J.; Harper S.; Hazuda D. J.; McHale C.; Monteagudo E.; Pucci V.; Rowley M.; Rudd M. T.; Soriano A.; Stahlhut M. W.; Vacca J. P.; Olsen D. B.; Liverton N. J.; Carroll S. S. MK-5172, a Selective Inhibitor of Hepatitis C Virus NS3/4a Protease With Broad Activity Across Genotypes and Resistant Variants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56 (8), 4161–4167. 10.1128/AAC.00324-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah U.; Jayne C.; Chackalamannil S.; Velazquez F.; Guo Z.; Buevich A.; Howe J. A.; Chase R.; Soriano A.; Agarwal; Rudd M. T.; McCauely J. A.; Liverton N. J.; Romano J.; Bush K.; Coleman P. J.; Grise-Bard C.; Brochu M.; Charron S.; Aulakh V.; Bachand B.; Beaulieu P.; Zaghdane H.; Bhat S.; Han Y.; Vacca J. P.; Davies I. W.; Weber A. E.; Venkatraman S. Novel quinolone-based P2-P4 macrocyclic derivatives as pangenotypic HCV NS3/4a protease inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 264–269. 10.1021/ml400466p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd M. T.; Butcher J. W.; Nguyen K. T.; McIntyre C. J.; Romano J. J.; Gilbert K. F.; Bush K. J.; Liverton N. J.; Holloway K. M.; Harper S.; Ferrara M.; DiFilippo M.; Summa V.; Swestock J.; Fritzen J.; Caroll S. S.; Burlein C.; DiMuzio J.; Gates A.; Graham D. J.; Hang Q.; McClain S.; McHale C.; Stahlhut M.; Black S.; Chase R.; Soriano A.; Fandozzi C.; Taylor A.; Trainor N.; Olsen D.; Coleman P.; Ludmerer S.; McCauley J. A. P2 quinazolinones and bis-macrocycles as new templates for next-generation hepatitis C virus NS3/4a protease inhibitors: Discovery of MK-2748 and MK-6325. ChemMedChem 2015, 10, 727–735. 10.1002/cmdc.201402558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.; Andrews S. W.; Condroski K. R.; Buckman B.; Serebryany V.; Wenglowsky S.; Kennedy A. L.; Madduru M. R.; Wang B.; Lyon M.; Doherty G. A.; Woodard B. T.; Lemieux C.; Geck D. M.; Zhang H.; Ballard J.; Vigers G.; Brandhuber B. J.; Stengel P.; Josey J. A.; Beigelman L.; Blatt L.; Seiwert S. D. Discovery of Danoprevir (ITMN-191/R7227), a Highly selective and Potent Inhibitor of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) NS3/4A Protease. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1753–1769. 10.1021/jm400164c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scola P. M.; Sun Q.-L.; Wang A. X.; Chen J.; Sin N.; Venables B. L.; Sit S.-Y.; Chen Y.; Cocuzza A.; Bilder D. M.; D’Andrea S.; Zheng B.; Hewawasam P.; Tu Y.; Friborg J.; Falk P.; Hernandez D.; Levine S.; Chen C.; Yu F.; Sheaffer A.; Zhai G.; Barry D.; Knipe J.; Han Y.-H.; Schartman R.; Donoso M.; Mosure K.; Sinz M.; Zvyaga T.; Good A.; Rajamani R.; Kish K.; Tredup J.; Klei H.; Gao Q.; Mueller L.; Colonno R.; Grasela D. M.; Adamas S.; Loy J.; Levesque P.; Sun H.; Shi H.; Sun L.; Warner W.; Li D.; Zhu J.; Meanwell N.; McPhee F. The discovery of asunaprevir (BMS-650032), an orally efficacious NS3 protease inhibitor for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1730–1752. 10.1021/jm500297k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P. W.; Llinàs-Brunet M.; Amad M.; Bethell R. C.; Bolger G.; Cordingley M. G.; Duan J.; Garneau M.; Lagacé L.; Thibeault D.; Kukolj G. Preclinical characterization of BI 201335, a C-terminal carboxylic acid inhibitor of the hepatitis C virus NS3-NS4A protease. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 4611–4618. 10.1128/AAC.00787-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scola P. M.; Wang A. X.; Good A. C.; Sun L.-Q.; Combrink K. D.; Campbell J. A.; Chen J.; Tu Y.; Sin N.; Venables B.; Sit S.-Y.; Chen Y.; Cocuzza A.; Bilder D. M.; D’Andrea S.; Zheng B.; Hewawasam P.; Ding M.; Thuring J.; Li J.; Hernandez D.; Yu F.; Falk P.; Zhai G.; Sheaffer A.; Chen C.; Lee M.; Barry D.; Knipe J.; Li W.; Han Y.-H.; Jenkins S.; Gesenberg C.; Gao Q.; Sinz M.; Santone K.; Zvyaga T.; Rajamani R.; Klei H.; Colonno R.; Grasela D.; Hughes E.; Chien C.; Adams S.; Levesque P.; Li D.; Zhu J.; Meanwell N.; McPhee F. Discovery and early clinical evaluation of BMS-605339, a potent and orally efficacious tripeptidic acylsulfonamide NS3 protease inhibitor for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1708–1729. 10.1021/jm401840s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau B.; O’Meara J. A.; Bordeleau J.; Garneau M.; Godbout C.; Gorys V.; Leblanc M.; Villemure E.; White P. W.; Llinas-Brunet M. Discovery of Hepatitis C Virus NS3–4a protease inhibitors with improved barrier to resistance and favorable liver distribution. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1770–1776. 10.1021/jm400121t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bara T.; Bhat S.; Biswas D.; Brockunier L.; Burnette D.; Chackalamannil S.; Chelliah M. V.; Chen A.; Clasby M.; Colandrea V.; Guo Z.; Han Y.; Jayne C.; Josien H.; Marcantonio K.; Miao S.; Neelamkavil S.; Pinto P.; Rajagopalan M.; Shah U.; Velazquez F.; Venkatraman S.; Xia Y.. HCV NS3 protease inhibitors. WO Pat. Appl. 2014025736, 2014.

- A table of pharmacokinetic data from iv/po dosing of rat and dog can be found in the Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.