Abstract

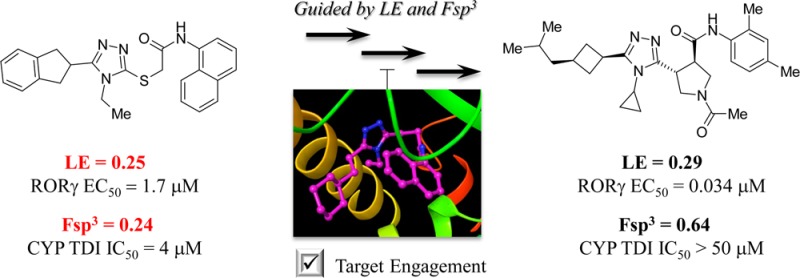

A novel series of RORγ inhibitors was identified starting with the HTS hit 1. After SAR investigation based on a prospective consideration of two drug-likeness metrics, ligand efficiency (LE) and fraction of sp3 carbon atoms (Fsp3), significant improvement of metabolic stability as well as reduction of CYP inhibition was observed, which finally led to discovery of a selective and orally efficacious RORγ inhibitor 3z.

Keywords: Th17, immunological diseases, nuclear receptor, RORγ, ligand efficiency (LE), fraction of sp3 carbon atoms (Fsp3)

Two decades after the discovery of Th1 and Th2 cells, a third subset of T helper cells called Th17 cells was identified and has drawn considerable attention since it was suggested to play a central role in the pathogenesis of various autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis.1,2 Among several regulatory pathways in which Th17 development and function are involved, the one regulated by the nuclear receptor RORγ appears to be crucial for controlling the differentiation and function.3 Given its validity as an emerging drug target for treatment of immunological diseases, many research groups have made significant efforts in the discovery of RORγ modulators in recent years.4−19

Since starting our RORγ inhibitor program in 2003, we discovered several structurally diverse hits after a HTS campaign.20 From these hits we selected compound 1 as the first hit-to-lead series for optimization. In addition to being reasonably potent against RORγ (hLUC EC50 = 1.7 μM, FRET EC50 = 0.85 μM), compound 1 also demonstrated >20-fold selectivity over five nuclear receptors (hRORα, hFXR, hRXRα, hPR, and hPPARγ) and was structurally unique in comparison to other nuclear receptor modulators.16−18

However, this compound has several drawbacks. For example, the microsomal stability in liver microsomes is poor with only 18% remaining at 10 min in human liver microsomes. It also has a modest time-dependent human CYP3A4 inhibition (IC50 = 4 μM) probably due to some reactive metabolites formed by the oxidation of 1. The ligand efficiency is only 0.25, far below the literature consensus value (0.30) for a drug-like molecule.21 The concept of ligand efficiency (LE) was first introduced by Kuntz22 and is widely accepted as a reliable index of drug-like qualities.23 Improvement of LE inevitably results in lower molecular weight and higher potency. We reasoned that a strategy of increasing LE and lowering the lipophilicity should therefore significantly improve the drug-like properties of compound 1. In addition, compound 1 is a rather flat molecule with a fraction of saturated carbons (Fsp3) of 0.24. Fsp3 is a newer index representing drug-likeness.24 Lovering et al. pointed out that a decrease of Fsp3 value would result in an increased incidence of CYP inhibition.25 The desired Fsp3 value is over 0.47 according to the literature.24 Thus, we considered that improvement of the poor Fsp3 value of compound 1 would be a rational way to overcome the CYP inhibition liability. As a result of the above analysis, we decided to optimize compound 1 by improving two drug-likeness metrics, LE and Fsp3, aiming to improve metabolic stability and reduce CYP inhibition.

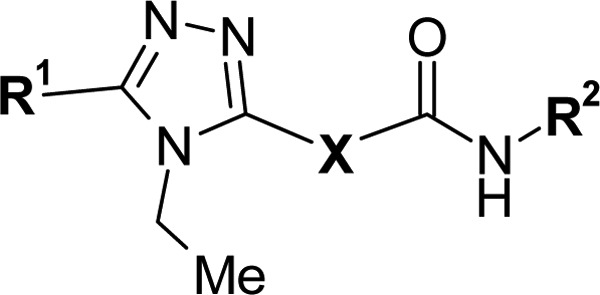

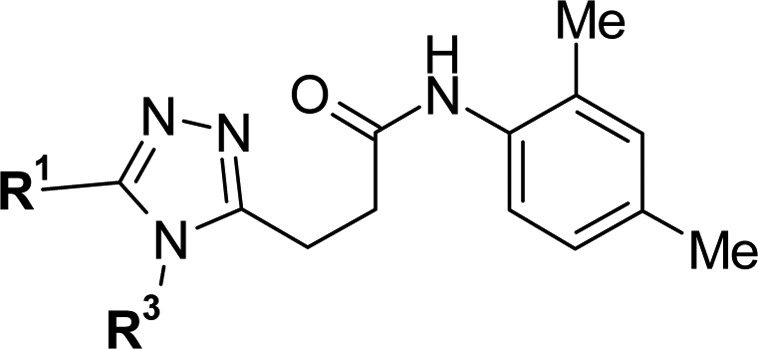

Initially, exploration of the sulfide portion was performed (2, 3a) and a carbon-substituted analogue 3a showed a slight improvement of ligand efficiency (Table 1). Introduction of a small substituent on the ethylene part of this molecule, however, afforded no further improvement (3b—3d). Thus, we chose 3a as a reference compound for further exploration. By changing the volume and shape of the substituents (3e—3j), we systematically examined the role of the R1 portion of the molecule, and 3g showed improved LE, while its Fsp3 value was doubled from that of 1. It is also noteworthy that the close analogue 3j showed reduced potency, which suggested that nonplanar substituents were preferred in this region of the binding pocket. For R2 exploration, disubstituted phenyl analogues26 were synthesized (3k—3m), and compound 3l showed significant improvements of both LE and Fsp3 (Table 1). We were encouraged to see such improvements, particularly because of the potential of 3l for further modifications.

Table 1. Initial SAR Exploration.

| RORγ-LUC EC50a (μM) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | X | R2 | human | mouse | LEb | Fsp3c |

| 1 | 2-indanyl | SCH2 | 1-naphthyl | 1.7 | 0.70 | 0.25 | 0.24 |

| 2 | OCH2 | >20 | >20 | <0.21 | 0.24 | ||

| 3a | (CH2)2 | 1.0 | 0.40 | 0.26 | 0.27 | ||

| 3bd | CH(Me)CH2 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.25 | 0.30 | ||

| 3cd | CH2CH(Me) | 1.3 | 0.67 | 0.25 | 0.30 | ||

| 3dd | CH(OH)CH2 | >20 | >20 | <0.20 | 0.27 | ||

| 3e | c-Hex | (CH2)2 | >20 | 4.5 | <0.23 | 0.43 | |

| 3f | c-HexCH2 | 14 | 2.6 | 0.23 | 0.46 | ||

| 3g | c-Hex(CH2)2 | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.48 | ||

| 3h | i-Pr(CH2)2 | 13.0 | 1.4 | 0.25 | 0.41 | ||

| 3i | t-Bu(CH2)2 | 6.7 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.43 | ||

| 3j | Ph(CH2)2 | 2.5 | 0.63 | 0.25 | 0.24 | ||

| 3k | c-Hex(CH2)2 | 3-Cl-2-Me-Ph | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.29 | 0.59 | |

| 3l | 2,4-di-Me-Ph | 0.90 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.61 | ||

| 3m | 3,5-di-Me-Ph | 2.9 | 3.1 | 0.27 | 0.61 | ||

The EC50s are mean values of at least two replicates.

LE = −1.37 log EC50(LUC hRORγ)/number of heavy atoms.

Fsp3 = number of sp3 hybridized carbons/total carbon count.

Racemic.

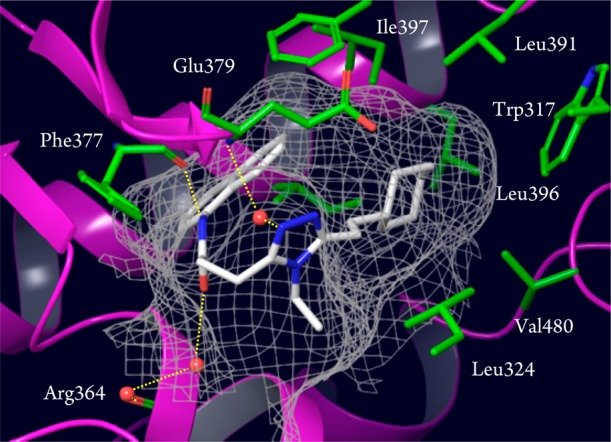

To confirm target engagement of the newly discovered RORγ inhibitors, we did an X-ray cocrystal analysis, which revealed that 3g binds to the ligand binding pocket of human RORγ with a unique U-shaped conformation (Figure 1). According to the structure, 3g made a direct hydrogen bond to Phe377 (2.97 Å), while the ligand formed water-mediated hydrogen bonds to both Arg364 (2.91 Å) and Glu379 (2.95 Å). The structure also suggested that the van der Waals contacts of the cyclohexylethyl moiety was important, and fine-tuning of this part was attempted later during the final optimization.

Figure 1.

X-ray structure of inhibitor 3g in human RORγ (PDB code 5AYG). Hydrogen bonds are depicted as dashed lines (yellow) and water molecules are shown as spheres (red).

Although 3l showed a favorable LE value, improvements on human CYP3A4 inhibition (IC50 = 12 μM) and metabolic stability (36% remaining at 10 min in human liver microsomes) were still unsatisfactory, thus further exploration was needed to obtain a selective RORγ inhibitor suitable for in vivo study.

A closer look at this molecule revealed that the compound contains several flexible C–C bonds, which result in entropic energy loss in order to maintain the binding conformation. In addition, these rotatable bonds may be contributing to the decent CYP inhibition profiles seen with these compounds.27 Therefore, we designed and synthesized some constrained analogues in an effort to stabilize the binding conformation and mask plausible metabolic sites simultaneously.

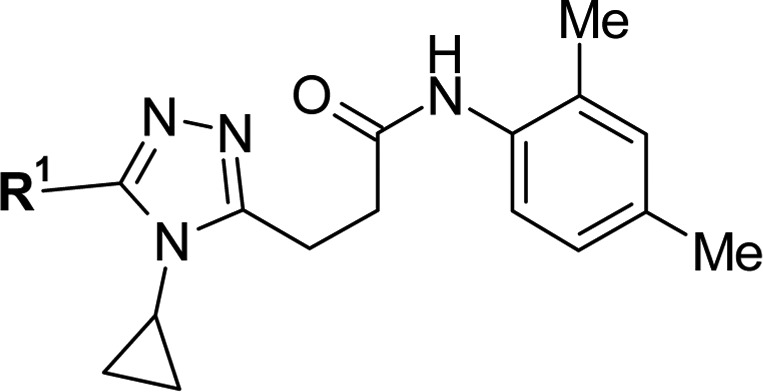

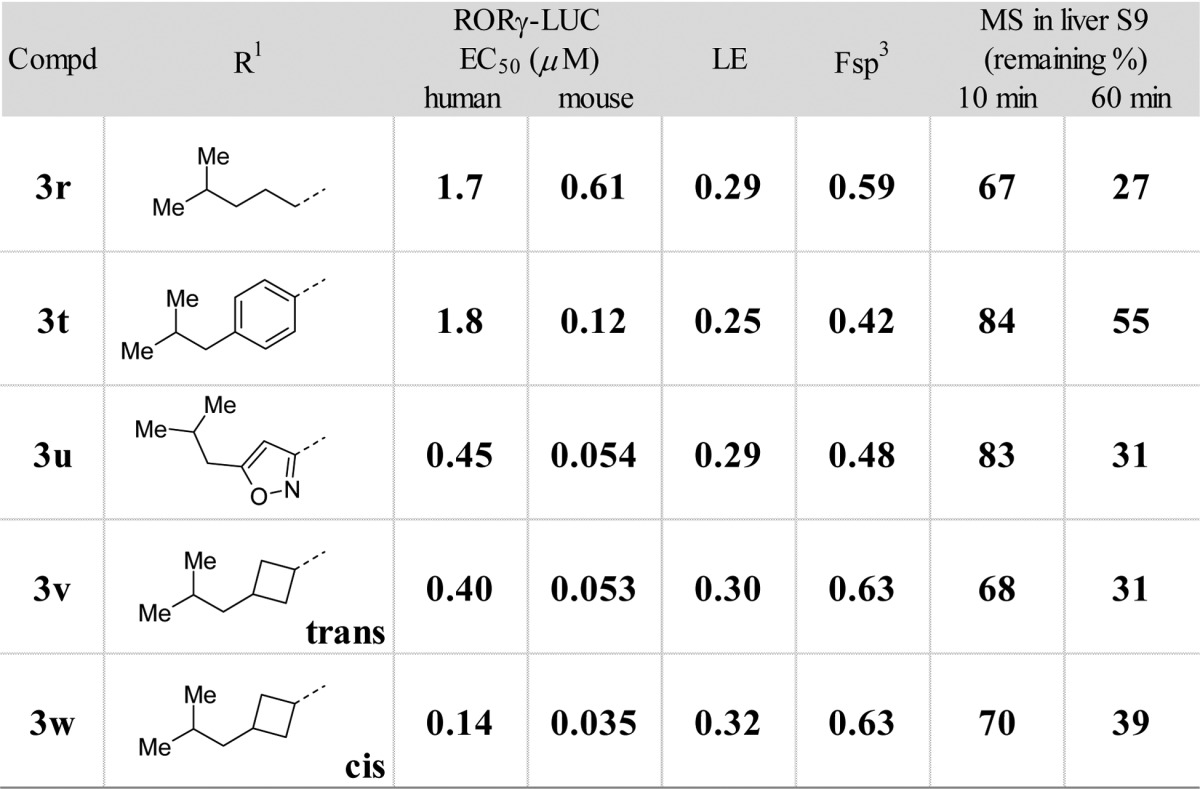

First, the ethyl group at the R3 portion was transformed into carbocycles, and the effect was examined (Table 2). As the size of the ring increased, we observed a decrease in the LE metric (3n—3p). However, compound 3n showed a marked improvement in metabolic stability with the least reduction of LE value. Therefore, this substituent was retained for further optimization. Our optimization of the R1 portion began with a brief investigation of the terminal position since relatively sharp SAR had been observed at this region during the initial SAR exploration. Compounds 3q–3s were synthesized as 3n analogues, and 3r showed a higher LE value with a slight increase of metabolic stability; thus, this terminal structure was chosen, and constrained subunits were inserted between this part and the triazole part.

Table 2. SAR of R1 Portion and R3 Portion.

| RORγ-LUC EC50a (μM) |

MS in liver S9 (remaining

%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | R3 | human | mouse | LE | Fsp3 | 10 min | 60 min |

| 3l | c-Hex(CH2)2 | Et | 0.90 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.61 | 36 | 0 |

| 3n | c-Pr | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 55 | 23 | |

| 3o | c-Bu | 9.5 | 1.8 | 0.23 | 0.64 | 49 | 27 | |

| 3p | 2,2-di-F-c-Pr | 0.92 | 0.50 | 0.27 | 0.63 | 75 | 59 | |

| 3qb | 2-Bu(CH2)2 | c-Pr | 3.9 | 1.4 | 0.27 | 0.59 | 63 | 27 |

| 3r | i-Pr(CH2)3 | 1.7 | 0.61 | 0.29 | 0.59 | 67 | 27 | |

| 3s | t-Bu(CH2)3 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 0.27 | 0.61 | 71 | 51 | |

The EC50s are mean values of at least two replicates.

Racemic.

Among the compounds shown in Table 3, 3w showed best LE value with a slight increase of metabolic stability. Most importantly, this compound’s potency reached a low submicromolar EC50 in the human LUC assay.

Table 3. Optimization of R1 Portiona.

The EC50s are mean values of at least two replicates.

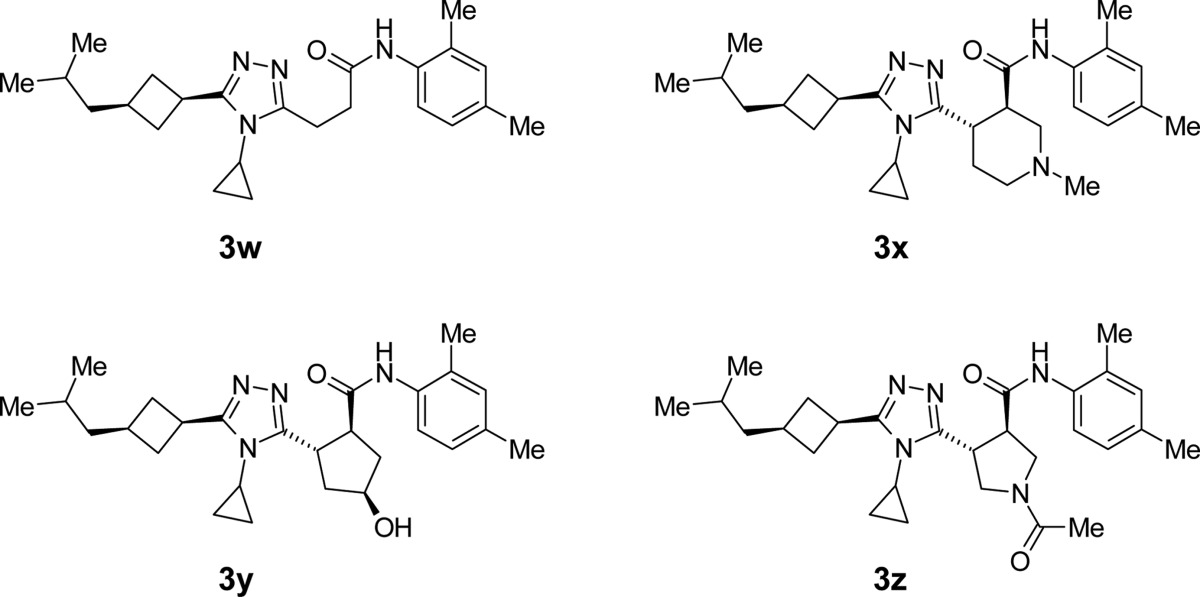

Finally, cyclic scaffolds were incorporated between the triazole ring and the amide bond to generate a U-shaped conformation best mimicking the binding mode required for this series of molecules. Among the 3w analogues listed in Table 4, 3y and 3z(28) showed good EC50 in the tens of nanomolar range, and most gratifyingly, 3z achieved the original goal of good metabolic stability as well as reduction of CYP inhibitory activity.

Table 4. SAR of 3w Analogues.

| RORγ-LUC EC50a (μM) |

MS in

liver S9 (remaining %) |

CYP3A4m (preincubation) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | human | mouse | LE | Fsp3 | 10 min | 60 min | IC50 (μM) |

| 3w | 0.14 | 0.035 | 0.32 | 0.63 | 70 | 39 | 5 |

| 3x″ | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.68 | 53 | 21 | |

| 3y | 0.098 | 0.038 | 0.29 | 0.67 | 87 | 76 | 3 |

| 3z | 0.034 | 0.029 | 0.29 | 0.64 | 86 | 61 | >50 |

The EC50s are mean values of at least two replicates.

Racemic.

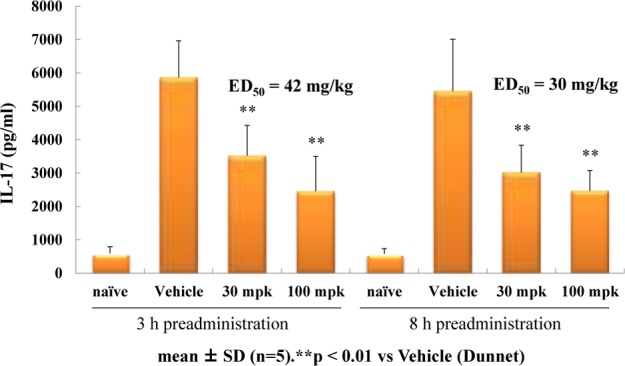

Given its most promising activity in terms of LUC potency as well as metabolic stability, 3z was considered the best choice for further investigations. An HCl salt of this compound was orally administered as a 0.5% methylcellulose suspension into mouse, and good bioavailability as well as a fair amount of plasma exposure (AUC0–inf) were observed at doses of 30 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg (see Supporting Information). Thus, 3z appeared to be a strong candidate for murine in vivo studies. The HCl salt of 3z was orally administered to mice that were stimulated with a mixture of MOG/PTX and a CD3 antibody. The plasma IL-17 level of each treated mouse was analyzed after 3 or 8 h of the administration (Figure 2). IL-17 release was suppressed in a dose-dependent manner, and both compound-treated groups showed similar results regardless of the difference in the plasma compound concentrations (the predicted free plasma concentration of 3z; 0.16 μM for 3 h/30 mg and 0.022 μM for 8 h/30 mg). Although the precise mechanism was not fully understood, it may suggest a delayed response of 3z toward RORγ signaling or the need of sustainable RORγ inhibition for the blockade of IL-17 production.

Figure 2.

Effect of compound 3z on the IL-17 level in a CD3-induced mouse PD model.

In summary, we have identified novel RORγ inhibitors. Lead optimization was conducted by optimization of two metrics, ligand efficiency and Fsp3. This strategy led to the discovery of a selective and orally efficacious RORγ inhibitor 3z. This compound also showed decent potency against human RORγ in the biochemical assay (FRET EC50 = 0.20 μM) with neither inhibitory activity against other nuclear receptors (EC50 > 20 μM; hRORα, hRORβ, hSF1, mGR, hRXRα, hVDR, hFXR, mLXRα, hPPARα, hPPARδ, hPPARγ, hPR, hRARα, hRARβ) nor time-dependent CYP inhibition properties (IC50 > 50 μM; hCYP3A4m, hCYP2C9, hCYP2D6, hCYP1A2, hCYP2A6, hCYP2C19). We demonstrated that the optimization of these two parameters provided an efficient and rational means to generate drug-like compounds that were metabolically stable with reduced CYP inhibition liabilities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jun-ichi Haruta for support. We are also grateful to Prof. Toshiya Senda and associate Prof. Noriyuki Igarashi at KEK-PF for supporting the synchrotron radiation experiments.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- RORγ

retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor gamma

- PR

progesterone receptor

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- SF1

steroidogenic factor 1

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- LXR

liver X receptor

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- LUC

luciferase

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00253.

Synthetic schemes, procedures, experimental data, stereochemical assignment of 3y and 3z, assay procedures, and PK profiles of 3z (PDF)

Author Present Address

# Corvus Pharmaceuticals Inc., 863 Mitten Road, Suite 102, Burlingame, California 94010, United States.

Author Present Address

∇ Janssen Research and Development, 3210 Merryfield Row, San Diego, California 92121, United States.

Author Present Address

○ Rebexsess Discovery Chemistry, 7819 Estancia Street, Carlsbad, California 92009, United States.

Author Present Address

◆ GIMDx Inc., 2440 Grand Avenue, Suite A, Vista, California 92081, United States.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper was published ASAP on November 9, 2015 with an incorrect version of the Supporting Information file. The corrected version was published ASAP on November 19, 2015.

Supplementary Material

References

- Harrington L. E.; Hatton R. D.; Mangan P. R.; Turner H.; Murphy T. L.; Murphy K. M.; Weaver C. T. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 1123–1132. 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.; Li Z.; Yang X. O.; Chang S. H.; Nurieva R.; Wang Y.-H.; Wang Y.; Hood L.; Zhu Z.; Tian Q.; Dong C. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 1133–1141. 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov I. I.; McKenzie B. S.; Zhou L.; Tadokoro C. E.; Lepelley A.; Lafaille J. J.; Cua D. J.; Littman D. R. The Orphan nuclear receptor RORγt directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 2006, 126, 1121–1133. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N.; Solt L. A.; Conkright J. J.; Wang Y.; Istrate M. A.; Busby S. A.; Garcia-Ordonez R. D.; Burris T. P.; Griffin P. R. The benzenesulfonamide T0901317 [N-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)-N-[4-[2,2,2-trifluoro-1-hydroxy-1-(trifluoromethyl)ethyl]phenyl]-benzenesulfonamide] is a novel retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor-α/γ inverse agonist. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010, 77, 228–236. 10.1124/mol.109.060905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N.; Lyda B.; Chang M. R.; Lauer J. L.; Solt L. A.; Burris T. P.; Kamenecka T. M.; Griffin P. R. Identification of SR2211: a potent synthetic RORγ-selective modulator. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012, 7, 672–677. 10.1021/cb200496y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solt L. A.; Kumar N.; He Y.; Kamenecka T. M.; Griffin P. R.; Burris T. P. Identification of a selective RORγ ligand that suppresses TH17 cells and stimulates T-regulatory cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012, 7, 1515–1519. 10.1021/cb3002649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh J. R.; Englund E. E.; Wang J.; Huang R.; Huang P.; Rastinejad F.; Inglese J.; Austin C. P.; Johnson R. L.; Huang W.; Littman D. R. Identification of potent and selective diphenylpropanamide RORγ Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 79–84. 10.1021/ml300286h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan P. M.; El-Gendy B. E.-D. M.; Kumar N.; Garcia-Ordonez R.; Lin L.; Ruiz C. H.; Cameron M. D.; Griffin P. G.; Kameneda T. M. Small molecule amides as potent RORγ selective modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 532–536. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Cai W.; Zhang G.; Yang T.; Liu Q.; Cheng Y.; Zhou L.; Ma Y.; Cheng Z.; Lu S.; Zhao Y.-G.; Zhang W.; Xiang Z.; Wang S.; Yang L.; Wu Q.; Orband-Miller L. A.; Xu Y.; Zhang J.; Gao R.; Huxdorf M.; Xiang J.-N.; Zhong Z.; Elliott J. D.; Leung S.; Lin X. Discovery of novel N-(5-(arylcarbonyl)thiozol-2-yl)amides and N-(5-(arylcarbonylthiophen-2-yl)amides as potent RORγt inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 692–702. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T.; Liu Q.; Cheng Y.; Cai W.; Ma Y.; Yang L.; Wu Q.; Orband-Miller L. A.; Zhou L.; Xiang Z.; Huxdorf M.; Zhang W.; Zhang J.; Xiang J.-N.; Leung S.; Qiu Y.; Zhong Z.; Elliott J. D.; Lin X.; Wang Y. Discovery of tertiary amide and indole derivatives as potent RORγt inverse agonists. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 65–68. 10.1021/ml4003875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauber B. P.; de Leon Boenig G.; Burton B.; Eidenschenk C.; Everett C.; Gobbi A.; Hymowitz S. G.; Johnson A. R.; Limatta M.; Lockey P.; Norman M.; Ouyang W.; René O.; Wong H. Structure-based design of substituted hexafluoroisopropanol-arylsulfonamides as modulators of RORc. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 6604–6609. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauber B. P.; René O.; Burton B.; Everett C.; Gobbi A.; Hawkins J.; Johnson A. R.; Liimatta M.; Lockey P.; Norman M.; Wong H. Identification of tertiary sulfonamides as RORc inverse agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 2182–2187. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauber B. P.; René O.; de Leon Boenig G.; Burton B.; Deng Y.; Eidenschenk C.; Everett C.; Gobbi A.; Hymowitz S. G.; Johnson A. R.; La H.; Liimatta M.; Lockey P.; Norman M.; Ouyang W.; Wang W.; Wong H. Reduction in lipophilicity improved the solubility, plasma–protein binding, and permeability of tertiary sulfonamide RORc inverse agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 3891–3897. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gege C.; Schlüter T.; Hoffmann T. Identification of the first inverse agonist of retinoid-related orphan receptor (ROR) with dual selectivity for RORβ and RORγt. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 5265–5267. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Niel M. B.; Fauber B. P.; Cartwright M.; Gaines S.; Killen J. C.; René O.; Ward S. I.; de Leon Boenig G.; Deng Y.; Eidenschenk C.; Everett C.; Gancia E.; Ganguli A.; Gobbi A.; Hawkins J.; Johnson A. R.; Kiefer J. R.; La H.; Lockey P.; Norman M.; Ouyang W.; Qin A.; Wakes N.; Waszkowycz B.; Wong H. A reversed sulfonamide series of selective RORc inverse agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 5769–5776. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenecka T. M.; Lyda B.; Chang M. R.; Grifin P. R. Synthetic modulators of the retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptors. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 764–776. 10.1039/c3md00005b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murali Dhar T. G.; Zhao Q.; Markby D. W. Targeting the nuclear hormone receptor RORγt for the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory disorders. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 2013, 48, 169–182. 10.1016/B978-0-12-417150-3.00012-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fauber B. P.; Magnuson S. Modulators of the Nuclear Receptor Retinoic Acid Receptor-Related Orphan Receptor-γ (RORγ or RORc). J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5871–5892. 10.1021/jm401901d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- René O.; Fauber B. P.; de Leon Boenig G.; Burton B.; Eidenschenk C.; Everett C.; Gobbi A.; Hymowitz S. G.; Johnson A. R.; Kiefer J. R.; Liimatta M.; Lockey P.; Norman M.; Ouyang W.; Wallweber H. A.; Wong H. Minor structural change to tertiary sulfonamide RORc ligands led to opposite mechanisms of action. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 276–281. 10.1021/ml500420y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thacher S.; Li X.; Babine R.; Tse B.. Modulators of retinoid-related orphan receptor gamma. US Patent US8389739, 2013.

- Abad-Zapatero C. Ligand efficiency indices for effective drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2007, 2, 469–488. 10.1517/17460441.2.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz I. D.; Chen K.; Sharp K. A.; Kollman P. A. The maximal affinity of ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 9997–10002. 10.1073/pnas.96.18.9997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A. L.; Groom C. R.; Alex A. Ligand efficiency: a useful metric for lead selection. Drug Discovery Today 2004, 9, 430–431. 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering F.; Bikker J.; Humblet C. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6752–6756. 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering F. Escape from Flatland 2: complexity and promiscuity. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 515–519. 10.1039/c2md20347b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S.; Newhouse B.; Anderson A. S.; Fauber B.; Allen A.; Chantry D.; Eberhardt C.; Odingo J.; Burgess L. E. Discovery and SAR of trisubstituted thiazolidinones as CCR4 antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 1619–1624. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veber D. F.; Johnson S. R.; Cheng H.-Y.; Smith B. R.; Ward K. W.; Kopple K. D. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Absolute stereochemistry of 3y and 3z was assigned based on the alignment of each enantiomer with the binding structure of 3g (Figure 1).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.