Abstract

We performed whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of 208 genomes from 53 families affected by simplex autism. For the majority of these families, no copy-number variant (CNV) or candidate de novo gene-disruptive single-nucleotide variant (SNV) had been detected by microarray or whole-exome sequencing (WES). We integrated multiple CNV and SNV analyses and extensive experimental validation to identify additional candidate mutations in eight families. We report that compared to control individuals, probands showed a significant (p = 0.03) enrichment of de novo and private disruptive mutations within fetal CNS DNase I hypersensitive sites (i.e., putative regulatory regions). This effect was only observed within 50 kb of genes that have been previously associated with autism risk, including genes where dosage sensitivity has already been established by recurrent disruptive de novo protein-coding mutations (ARID1B, SCN2A, NR3C2, PRKCA, and DSCAM). In addition, we provide evidence of gene-disruptive CNVs (in DISC1, WNT7A, RBFOX1, and MBD5), as well as smaller de novo CNVs and exon-specific SNVs missed by exome sequencing in neurodevelopmental genes (e.g., CANX, SAE1, and PIK3CA). Our results suggest that the detection of smaller, often multiple CNVs affecting putative regulatory elements might help explain additional risk of simplex autism.

Introduction

The underlying genetic etiology of autism (MIM: 209850) has been an area of intense focus and has benefited considerably from advances in sequencing technology. On the basis of twin studies1, 2 and syndromic forms of the disease,3, 4 autism is known to have a genetic component. With the application of exome sequencing and copy-number variation (CNV) microarrays to large collections of individuals with autism, the genetic architecture of autism has become clearer. Rare and, in particular, de novo variants that disrupt the protein-coding portions of genes and large CNVs are now estimated to contribute to 30% of the diagnoses of simplex autism.5 In addition, another 7% of cases have been attributed to variants in genes with a residual variation intolerance score (RVIS)6 < 50, private to a family, and inherited from the mother.7 One strategy for solving the remaining ∼60% is to explore the genome for genetic variants of large effect in families who are already known to be negative for any obvious potential causal variation (de novo likely gene-disruptive [LGD] mutations or large CNVs).

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) is increasingly becoming more affordable,8 providing access to a more comprehensive spectrum of genetic variation than is available with previous genomic technologies, including exome sequencing, SNP microarrays, and array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), especially within noncoding and potentially regulatory9, 10 regions of the genome.11 Previous publications have suggested that most of the protein-coding sequence is covered sufficiently well by WGS,8 which actually provides better coverage12 than WES technology. Early comparisons, however, were limited. A study of individuals with intellectual disability, for example, made a comparison by using different platforms, i.e., exomes generated by SOLiD or genomes sequenced with Complete Genomics technology. The authors reported a dramatic increase in diagnostic yield as high as 42% for individuals who were previously negative for microarray or exome sequencing,12 although it was difficult to disentangle these differences from sequence and coverage differences. Another study compared both Illumina WES and WGS but was limited to six individuals.13 Finally, a more recent analysis of exome and genome sequencing provided a comparison of multiple exome and genome platforms but focused only on a subset of clinically relevant genes14 as opposed to the whole genome.

In the present study, we specifically compared WGS on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform to WES on the NimbleGen capture and Illumina sequencing platforms on the same samples. There were two aims. The first was to understand the yield and technological limitations of both WGS and WES approaches in detection of SNVs and CNVs on a sufficiently large sample collection. The second was to assess whether there is any genetic signal for rare and private noncoding regulatory mutations in individuals with idiopathic autism. Using the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform, we initially focused on 160 individuals from 40 quads with a single proband with autism for which no likely pathogenic CNV or SNV had been originally identified in 39 families (phase I). We performed a follow-up study on another 13 trios with a single autistic proband and three control families by using standard HiSeq 2000 technology (phase II) in order to increase power.

Material and Methods

Phase I families (n = 39) for whom no de novo LGD mutations5, 15, 16, 17, 18 or large CNVs19, 20 had been observed in the proband in previous exome and SNP microarray analyses (Figure S1) were selected for WGS from the Simons Simplex Collection (SSC). In addition, one family with a known LGD mutation served as a “control” family for variant detection. We were blinded to this sample initially given that families were selected at the Simons Foundation, and when we detected the event (splice site in TCF7L2 [MIM: 602228] in proband 13069.p1), we reported to Simons, and they informed us that it was already known. Genomic DNA derived from blood was sequenced to an average depth of 31.1× ± 4.5× (Figure S2A) with an Illumina HiSeq X Ten sequencer at the New York Genome Center (full statistics are shown in Tables S1–S4 and Figure S2). We evaluated the quality of each genome by mapping WGS reads with mrsFAST21 to the human reference genome (GRCh37, 1000 Genomes), estimating copy number across the entire genome in 500 bp windows (100 bp sliding), and calculating the proportion of known copy-number-invariant regions that were properly called as copy number 2 (diploid) in each genome. The analysis identified four samples (11572.s1, 12175.s1, 12568.s1, and 13023.mo) that did not meet our threshold of >85% “diploidy” (Figure S3A). We used mitochondrial-genome characterization and KING22 analysis on nuclear genome SNV data to confirm all familial relationships. For the mitochondrial genome, we identified an average of 25 inherited events per family (Tables S5 and S6) and a trend toward excess heteroplasmy in probands (n = 4) rather than siblings (n = 2) (one-sided Fisher’s p = 0.34, odds ratio [OR] = 2.09). We also sequenced 13 trios from the SSC and three control trios from the National Children’s Study (phase II) locally to a median mapped coverage of 51× on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument. Once again, autism trios were selected if they contained no large CNVs according to an aCGH platform23 or any LGD events revealed through exome sequencing. Between the time the phase II samples were sequenced and this study, it was determined by array that one of these families already contained a known event in TMLHE (MIM: 300777) in proband 11000.p1.24 The institutional review board (IRB) of the University of Washington (IRB 46179) approved this study.

We called SNVs in the phase I genomes by using the Genome Analysis Toolkit v.3.2-2 (GATK best practices) HaplotypeCaller25, 26 and FreeBayes v.0.9.14-20-g5dc4d5e (Figure 1)27 in addition to Platypus28 to potentially improve indel sensitivity. Private SNVs and indels were defined as those identified by GATK and FreeBayes (intersection) as having an allele count equal to 1 in parents in this study and not present in dbSNP build 138. De novo SNV and indel discovery was achieved with software DNMFilter29 and TrioDeNovo.30 In the phase II genomes, reads were mapped with BWA-mem v.0.6.131 against GRCh37, and SNVs were called with GATK v.2.7-2 UnifiedGenotyper. Variant quality-score recalibration was applied and excluded tandem repeats, segmental duplications, and dbSNP 129 positions falling in or before release 129. Samples were split into trio variant call format (VCF) files containing entries for mother, father, and proband from each family. Potential de novo SNVs were selected if the alternate allele count in the parents was <2, and a subset of high-confidence SNVs were selected for validation by molecular inversion probe (MIP) resequencing32 after the call was observed with the Integrated Genomics Viewer.33 We used ForestDNM34 on each trio to select putative de novo variants. Variants with a score > 0.7 were considered high-confidence variants and included in the analysis. For de novo indels, we additionally required an allele balance in the proband of 0.25–0.75, no alternate reads present in the parents, and a minimum alternate allele count of 5 in the proband. We used SeattleSeq Annotation 138.835 to annotate SNVs and indels.

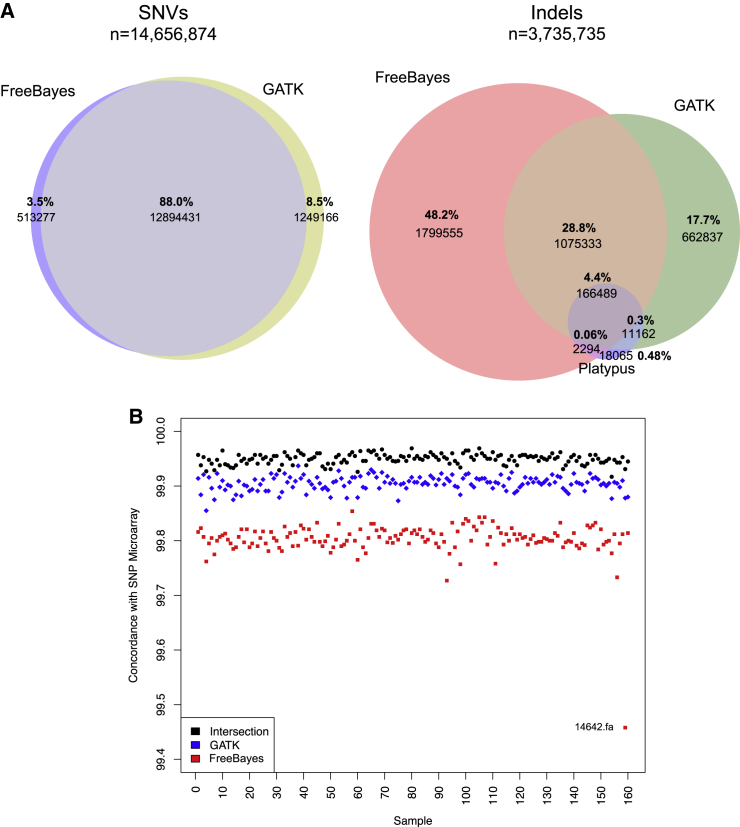

Figure 1.

SNV and Indel Analysis

(A) Venn diagram of SNV calls from FreeBayes and GATK and Venn diagram of indel calls from FreeBayes, GATK, and Platypus.

(B) Concordance by sample between variant calls from FreeBayes, GATK, or their intersection (FreeBayes and GATK) and exome-chip data. Variants shown are those passing filters. These data were available for all samples (n = 232,961 variants, of which 44,732 were identified in the genome VCF file). SNP concordance with exome SNP microarrays was 99.80% ± 0.03%, 99.90% ± 0.01%, and 99.95% ± 0.03% for FreeBayes, GATK, and the intersection of FreeBayes and GATK call sets, respectively.

We called CNVs in phase I genomes by using digital comparative genomic hybridization (dCGH),36 GenomeSTRiP,37 and VariationHunter38 (Figure 2). We merged all CNV calls to a minimal set by combining events with at least 25% reciprocal overlap and breakpoints that were <1,500 nucleotides from each other on both ends. This was applied uniformly to all samples and merged most CNVs, although a few remained unmerged because of separation by segmental duplications or large repeats. For exome-genome comparisons, we used exome calls from XHMM39 and CoNIFER40 as described previously.7 For phase II genomes, CNV calling was limited to VariationHunter (trio-aware CommonLAW)38 and GenomeSTRiP.37

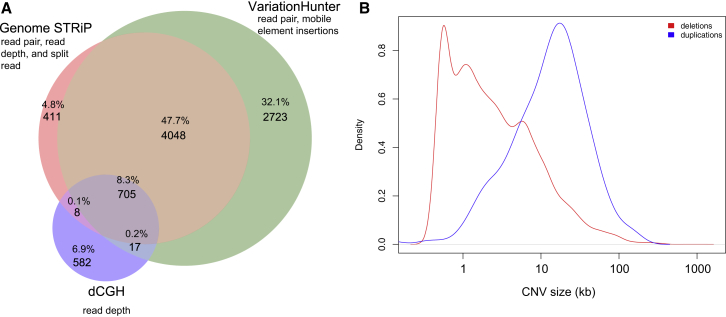

Figure 2.

CNV Analysis

(A) Venn diagram of CNV calls from dCGH, GenomeSTRiP, and VariationHunter.

(B) Density of size for deletions and duplications. CNVs were initially merged if they had at least 25% reciprocal overlap and their breakpoints were <1,500 nucleotides away from each other at both ends. To get a very minimal set, we subsequently merged CNVs by using a greedy merge in BEDTools.

Genic, putative regulatory and repeat-associated variants were annotated with SAVANT.41 Minor allele frequency was estimated with dbSNP42 build 138, and a CNV morbidity map was established on the basis of 29,085 case and 19,584 control individuals in whom large (>100 kb) events had been characterized.43 SNP and CNV genotypes were determined with the Illumina Human Exome 12 v.1.2 exome chip, Illumina whole-genome SNP microarray data,19 and comparison to exomes (NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Exome Kit v.2 [based on UCSC Genome Browser hg19] and Illumina sequencing) for which BAM and VCF files were available.7 DNase I hypersensitive sequencing sites were determined on the basis of sequencing of normal human fetal CNS tissues, including 13 brain samples (ages: post-conception days 85–142) and five spinal-cord samples (ages: post-conception days 87–113). After sequencing, the reads were aligned to the human genome, and peaks were called with the Hotspot algorithm44 using a false-discovery rate (FDR) of 1%. Herein, references to putative regulatory regions refer to these CNS DNase I sites, and putative regulatory variants were considered to be those falling within these regions or with a phyloP score > 4 according to the USCS 46-way alignment. De novo SNVs and indels identified in autistic individuals were collected from the literature5, 7, 15, 16, 17, 18, 32, 45 and re-annotated together. Testing for enrichment of de novo events was performed as described previously32 for LGD, missense, and combined LGD and missense events. A high-confidence set of 57 genes associated with autism risk was generated by the selection of genes with three or more de novo missense and/or LGD events in autistic individuals, one or fewer de novo missense events, and no LGD mutations in control individuals,5, 7 as well as a p value < 0.01 in at least one of the three tests. Enrichment of noncoding putative regulatory regions was tested within regions including and around genes where de novo mutations had been identified. These regions included the transcription start to the transcription stop and extended out from the gene by a given distance (d).

We attempted validation on 691 candidate de novo SNVs and indels in phase I by using Sanger and Pacific Biosciences sequencing. We focused on sites mapping to coding regions and putative, noncoding regulatory elements. In phase II, we used MIP resequencing to validate a subset of putative de novo SNVs and indels.32 In particular, we made MIP pools for each trio individually and ran mother, father, and proband. Events detected by both GATK and FreeBayes showed the highest validation rate (VR = 89.1%); these were followed by events detected only by GATK (VR = 28.9%) and finally events detected by FreeBayes alone (VR = 10.6%) (Table S7). DNMFilter consistently outperformed TrioDeNovo for de novo calling within trios. Events called by both DNMFilter and TrioDeNovo had the highest rate (VR = 97.8%), and these were followed by those only called by DNMFilter (VR = 65.5%) and finally events called only by TrioDeNovo (VR = 52.0%) (Table S7). For exonic regions, there were a total of 141 experimentally validated de novo mutations in 80 children. To look at various features important in de novo validation, we performed analysis with random forests46 and conditional inference trees,47 similar to the analysis we performed on variants from exome sequencing.7

We used two different approaches to validate CNVs. First, we utilized available whole-genome Illumina SNP microarray data and exome-chip data and applied Corrected Robust Linear Model with Maximum Likelihood Classification (CRLMM) software48, 49 to generate probe-level copy-number estimates as described previously.7 We compared different thresholds on the basis of the number of SNP microarray probes intersecting a CNV (≥5, ≥10, or ≥20) and assessed ∼10% of all CNVs with this approach. Site VRs (whether the site was confirmed in at least one person) were 91.3%, 96.8%, and 97.9% for deletions and 85.6%, 94.4%, and 95.2% for duplications at the ≥5, ≥10, and ≥20 thresholds, respectively. Genotype concordance, however, was significantly reduced at 60.9% (≥5 probes), 67.7% (≥10 probes), and 65.7% (≥20 probes) for deletions, whereas duplications had a genotype concordance of 40.6% (≥5 probes), 49.6% (≥10 probes), and 68.9% (≥20 probes).

In the second approach, we designed a customized microarray (Agilent) for aCGH validation. We targeted 2,002 CNV regions, including all candidate de novo CNVs and all rare, inherited events that had a frequency ≤ 4 and that either overlapped an exon or CNS DNase I hypersensitive site or were in a highly conserved region with a maximum phyloP score > 4. The 4×180K Agilent microarray contained 166,175 probes targeting the CNV regions. VRs were very high for events detected by all three callers (98.5%). For unique calls, dCGH showed the highest validation (92.2%) and was followed by GenomeSTRiP (89.1%) and lastly VariationHunter (38.2%). We note that sensitivity ranged by a factor of 3 for these different callers, reflecting the challenge of maintaining a low FDR as part of CNV discovery. Moreover, it is often difficult to validate events < 2 kb in size by aCGH.

We identified 12 CNS DNase I hypersensitive sites within the 14 kb deletion of DSCAM (MIM: 602523) in family 11572, and all were selected for functional testing. Nine sequence intervals (150–630 bp), encompassing either one or two of the 12 CNS DNase I hypersensitive sites within the interval, were synthesized as gBlocks (IDT) to be flanked by modified Gateway arms.50 Sequences separated by ≤100 bp were grouped into a common interval for the transgenic assay. The gBlocks were cloned (Gateway LR Clonase) into the pTEA vector, a version of pT2cfosGW51, 52 modified to express the red fluorescent reporter tdTomato, for injection into zebrafish embryos. Zebrafish were maintained as previously described.53, 54 At least 150 embryos were injected per construct at the 1- to 2-cell stage with tol2 transposase RNA as previously described.51, 52 Injected (mosaic) embryos were screened for tdTomato expression at 48 hr post fertilization (hpf). Mosaic embryos were scored positive if they had robust tdTomato CNS expression. The >20% threshold is an empiric cutoff used for determining the likelihood that injected constructs will show that same tissue expression when it is transmitted through the germline. Because all constructs showed CNS expression in >20% embryos, the results are consistent with strong drivers of expression. Embryos were then live imaged at 48 hpf with a Nikon AZ100 Multizoom microscope with NIS-Elements AR 3.2 64 bit software.

Results

SNV and Indel Discovery and Analysis

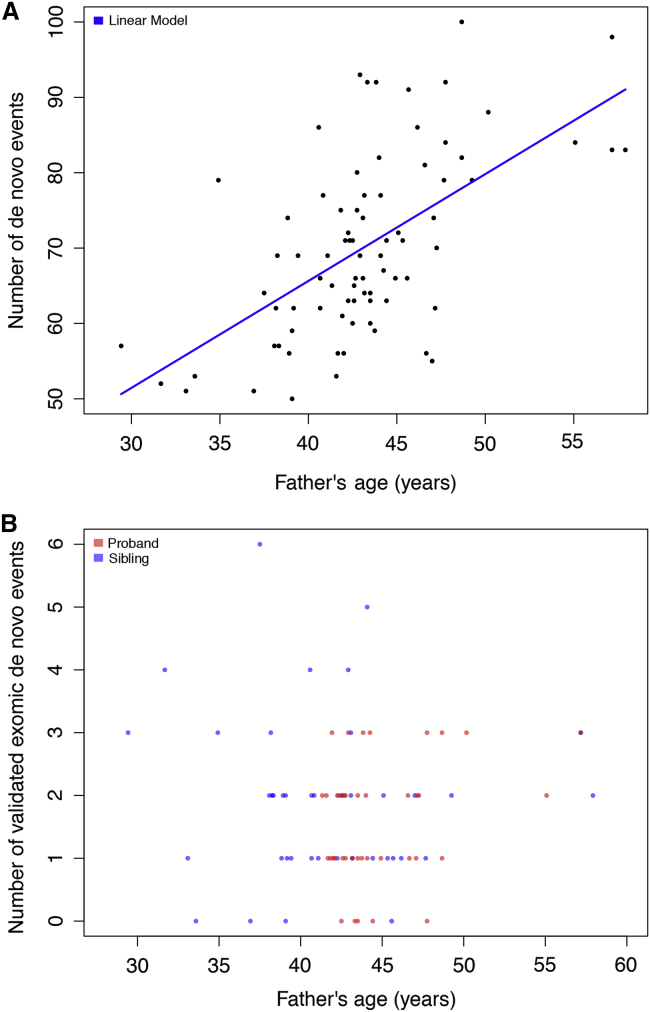

Applying two SNV and indel callers to WGS data, we identified 1,563,113 private or rare variants detected in the intersection of GATK and FreeBayes in probands and siblings. WGS SNP call sets were high according to a comparison to SNP microarrays (>99%) (Figure 1B). WES call sets showed lower concordance with WGS data (99.08% ± 0.83%) than with SNP microarray genotypes (99.96% ± 0.02%) (Figure S4). Although we observed no significant difference between probands and siblings in terms of overall variant counts (Table S8), probands showed a slight excess of highly conserved missense variants (phyloP > 4) in genes associated with autism risk variants (ten in probands versus seven in siblings). We initially identified 5,609 de novo SNVs and indels by using DNMFilter (70.1 ± 12.0 variants per individual). De novo variants showed evidence of nonrandom clustering (Figure S5), and the number of new mutations significantly correlated with paternal age (Figure 3A) as described previously.18, 55 Application of a second caller, TrioDeNovo, discovered an additional 2,341 variants (missed by DNMFilter), albeit with a lower VR. In total, we detected 7,978 de novo events (7,936 SNVs and 42 indels) and an overall VR of 75.2% for tested variants (Table S7). The most common cause of false positives was under-calling in the parent (which can be approximated by a probability score in DNMFilter; see Figures S6–S10 and, for a full table with features, Table S9).

Figure 3.

Paternal Age and De Novo Events

(A) Paternal age for de novo SNVs and indels. Probands generally have older fathers. The number of variants was significantly correlated with paternal age (Pearson correlation p = 7.9 × 10−9, r = 0.59). The data fit a linear trend (adjusted r2 = 0.34) with advancing paternal age (p = 7.9 × 10−9) such that there are on average 1.4 [0.98, 1.9] de novo mutations for each year of a father’s life. In this study, the father’s age at the time of the child’s birth ranged from 29.4 to 57.9 years.

(B) Paternal age for de novo SNVs and indels within the exome. The number of de novo events detected in each individual is plotted against the father’s age when the individual was born. Shown in blue are siblings, and in red are probands.

CNV Discovery and Analysis

We identified a total of 388,538 CNV events corresponding to 9,917 distinct genomic regions in the 160 phase I genomes. Overall, probands showed slightly more (n = 101,257) than siblings (n = 95,727; one-sided paired t test p = 1.8 × 10−3). Leveraging available SNP microarray data for 140 samples, we validated CNVs by using a custom permutation test and CRLMM (see Material and Methods, Figure S11, and Tables S10 and S11). Requiring a minimum of ten SNP microarray probes, we obtained site VRs of 96.8% for deletions and 94.4% for duplications, although genotyping concordance was significantly lower (Material and Methods). To further assess the validation of rare and de novo events, we applied a targeted aCGH approach. We tested 1,529 rare, inherited, and de novo CNVs in all 80 probands and siblings (n = 40 quads) and obtained an overall VR of 91.9% (Table S12). We validated five de novo CNVs in these families (two in probands and three in siblings). The de novo events included an SAE1 (MIM: 613294) exonic duplication (52 kb) in proband 13874.p1 and a CANX (MIM: 114217) promoter and exon 1 deletion (6 kb) in proband 14153.p1. Sibling de novo events included ATP2C2 (MIM: 613082) and TLDC1 deletions (84 kb) in sibling 13874.s1, PMAIP1 (MIM: 604959) and MC4R (MIM: 155541) duplications (1.3 Mb) in sibling 13023.s1, and an EIF5B (MIM: 606086) deletion (6 kb) in sibling 12175.s1. Restricting our analyses to the 3,193 de novo and private CNVs (which were identified in only one family in our study and had a frequency < 0.1% in 19,584 control individuals) in probands (n = 1,589) and siblings (n = 1,604), we found no significant difference in size, genic content, or transmission bias between siblings and probands, possibly because of the CNV exclusion criteria for probands (Table S13). Considering all genic regions in the human genome, we found no enrichment of noncoding putative regulatory CNV events in probands (n = 417 in probands versus n = 449 in siblings).

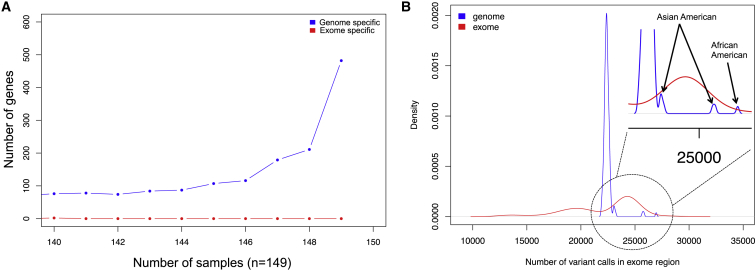

Exome versus Genome

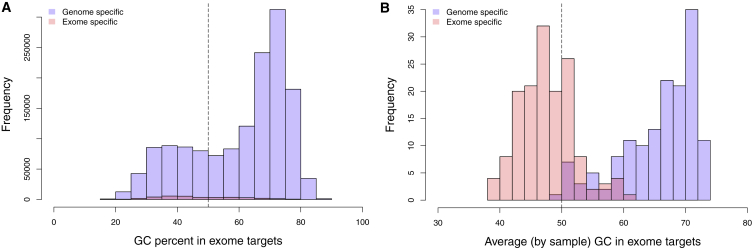

Sequence coverage was predictably13, 56 more uniform by WGS (36.6× ± 5.4×) than by WES (81.2× ± 38.6×) (Figure S12). WGS-only regions were higher in GC content (60.4% ± 0.2%, p < 2.2 × 10−16) than were WES-only regions (47.4% ± 0.1%) (Figure 4). WGS recovered 1,854 genes that were missing WES data for >90% of samples, whereas WES detected only two genes (ATP6V1G3 and SLCO1B1 [MIM: 604843]) that were missing WGS data in >90% of samples (Figure 5). Consequently, SNV and indel calling within exome targets was also more uniform by WGS (22,464 ± 578) than by WES (22,172 ± 3,207) (Figure 5). In the genome, the variability was primarily driven by ancestry (Figure S3B), and no such effect was seen in the exome calls, which showed rather stochastic variability across samples. Combining the WES and WGS data, we identified 176,131 exonic SNV and indel events. Of these, 53.9% were found by both WES and WGS, 35.2% were detected by WGS, and 10.8% were detected by WES.

Figure 4.

Exome versus Genome: GC Bias

(A) Percentage of GC content in exome-specific sequencing and genome-specific sequencing regions within the exome.

(B) Percentage of average GC content by sample of exome-specific sequencing and genome-specific sequencing regions within the exome. Genome-specific regions are defined as those at >10× coverage in the genome and <10× coverage in the exome. Exome-specific regions are defined as those at >10× coverage in the exome and <10× coverage in the genome. Genome-specific regions are higher in GC content (Wilcoxon p < 2.2 × 10−16).

Figure 5.

Exome versus Genome: Gene Coverage

(A) Number of genes that have regions covered in exome-specific sequencing or genome-specific sequencing regions of the exome and the number of samples in which they occur. Genome-specific regions of the exome add an additional ∼2 Mb (5%) of sequence, whereas exome-specific regions add an additional ∼40 kb. Genome sequencing detected 1,854 genes missing sequences in >90% of individuals targeted by exome sequencing, whereas exome sequencing identified only two genes missing sequences in >90% of samples targeted by genome sequencing. Among the genes ascertained only by WGS, those of interest in relation to autism include ACHE (MIM: 100740), AGAP2 (MIM: 605476), ARID1B, CACNA2D3 (MIM: 606399), DEAF1 (MIM: 602635), EFR3A (MIM: 611798), FOXP1 (MIM: 605515), LAMC3 (MIM: 604349), MYO1E (MIM: 601479), PRKAR1B, RANBP17 (MIM: 606141), RUFY3 (MIM: 611194), SHANK3 (MIM: 606230), and TRIO.

(B) Density plots of the number of variants (intersection of FreeBayes and GATK) called in the exome-by-exome sequencing and by genome sequencing. Shown is the uniformity of calls in the genome data where only ancestry is a contributor to the difference between samples. Of note, exome data are exceedingly variable in the number of variant calls.

In general, WES-specific sites showed higher sequence coverage (Wilcoxon p < 2.2 × 10−16), but examination of the unfiltered VCF files from WGS recovered most of these (93.7%), suggesting that the exclusion was a result of filters applied to the VCF files. Similarly, 78.9% ± 10.5% of WGS-specific sites within exome capture sites could be recovered in the raw exome VCF files (Figure S13). Ultimately, 3.1% and 3.0% of sites were WES and WGS specific, respectively. We combined data from our current study and from previously published exome studies to obtain the most comprehensive set of de novo variants in the protein-coding regions of these samples (Table S14). There were 210 such variants, of which 173 resided within the NimbleGen exome-capture regions. Of these events, 105 (VR = 93.3%, n = 104 tested) were detected by both exome and genome sequencing, 21 (VR = 35.0%, n = 20 tested) were detected by only exome sequencing, and 47 (VR = 37.1%, n = 35 tested) were detected only by genome sequencing. Overall, we estimate 1.8 ± 1.2 validated de novo exonic mutations per child, which is significantly higher than many of the earlier exome reports. These findings highlight the value of combining WGS and WES to maximize SNV sensitivity. However, fully determining the extent will require much larger sample sizes. With respect to CNVs, WES provided no additional gain in sensitivity (Figures S4B and S14). Moreover, events detected by WGS were 3-fold smaller (10 ± 24 kb, median = 2 kb) than those detected by WES analysis (38 ± 64 kb, median = 7 kb; Wilcoxon p = 1.4 × 10−7). Our comparison of CNV calls from WGS and SNP microarrays also indicated detection of additional CNVs by WGS: 6,898 smaller CNVs less than 50 kb were not detected by CNV calling in SNP microarrays (Figure S15).

Smaller CNV and Noncoding Putative Regulatory Mutations in Autism Genomes

In this study, we specifically focused our analysis on noncoding de novo SNVs and indels. In particular, we restricted our analysis to putative regulatory sites, defined as sites in a fetal human CNS DNase I hypersensitive region and/or at a highly conserved base (phyloP score > 4, UCSC 46-way alignment). We attempted Sanger or Pacific Biosciences validation on all such regulatory sites in phase I and combined the validated events with all events identified in the intersection of FreeBayes and GATK (VR = 89.1%) to generate a high-confidence de novo SNV and indel dataset. These data contained 204 noncoding putative regulatory events in probands and 171 in siblings, which did not meet significance (p = 0.07, paired t test) after we accounted for paternal age.

Although it was underpowered, we repeated the analysis by limiting to 57 genes where an excess of recurrent de novo mutations had been identified in probands on the basis of recent exome sequencing studies of families affected by simplex autism5, 32, 57 (Table S15). We hypothesized that these genes associated with autism risk might harbor more noncoding putative regulatory variants in probands given that such mutations would be more likely to affect dosage, as has been observed for Mendelian diseases.58 Because regulatory elements can exist at least as far as 1 Mb11 away from the gene, we tested various distance intervals (d) on either side of the transcription start and end of each gene. We consistently found an excess of de novo SNV and indel variants in probands, although none reached statistical significance (lowest p = 0.27, Fisher’s exact test).

We also examined CNVs for the same effect. Validation by aCGH, SNP microarray, or PCR was attempted on all de novo and private CNVs identified in the phase I genomes (n = 2,002). From this high-confidence set, we defined 1,202 validated de novo and private CNVs with at least one DNase I hypersensitive base. As with SNVs, we found a slight excess of events in probands at all distance intervals (lowest p value = 0.09 at d = 100 kb), which contained five events in probands (DSCAM, FAT3 [MIM: 612483], PRKAR1B [MIM: 176911], TRIO [MIM: 601893], and ZC3H4) but only a single event in siblings (PAX5 [MIM: 167414]). A combined analysis with de novo SNVs and private CNVs showed greater enrichment around genes where an excess of de novo protein-coding variants had been identified. This occurred especially in proximity to the gene (d = 25 kb [p = 0.12], d = 50 kb [p = 0.07], and d = 100 kb [p = 0.06]). In order to increase power, we tested for enrichment around autism-associated genes by using a larger set of samples sequenced locally (phase II genomes). We integrated genome sequence data from an additional 13 affected trios and 3 unaffected trios for a total of 53 autism genomes and 43 unaffected siblings or control individuals. We found modest yet statistically significant enrichment of potentially disruptive events close to genes associated with autism risk (d = 25 kb [p = 0.03], d = 50 kb [p = 0.03], and d = 100 kb [p = 0.04]; varying d shown in Table 1). Thus, three of the six tests showed nominal significance, and significance dropped off as distance increased. The set includes de novo SNVs (Table 2) and CNVs (Table 2) near DSCAM, SCN2A (MIM: 182390), TRIO, NR3C2 (MIM: 600983), and PRKCA (MIM: 176960) and multiple events associated with ARID1B (MIM: 614556) (Figure 6). Replication of this effect is required and will be testable with larger sample sizes in the future.

Table 1.

Enrichment of Mutations in Putative Regulatory Elements

| Variant Category |

Autism |

Control |

Fisher’s One-Sided p Value | Confidence Interval | Fisher’s OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Count | Genes Associated with Autism Risk Variants | Variant Count | Genes Associated with Autism Risk Variants | ||||

| Total | 3,787 | – | 2,997 | – | – | – | – |

| Noncoding Putative Regulatory | |||||||

| d = 10 kb | 5 | ARID1B (2), PRKCA, DSCAM, SCN2A | 0 | – | 0.05 | [0.96, inf] | inf |

| d = 25 kb | 6 | ARID1B (2), NR3C2, PRKCA, DSCAM, SCN2A | 0 | – | 0.03 | [1.22, inf] | inf |

| d = 50 kb | 6 | ARID1B (2), NR3C2, PRKCA, DSCAM, SCN2A | 0 | – | 0.03 | [1.22, inf] | inf |

| d = 100 kb | 8 | ARID1B (2), NR3C2, PRKCA, PHYIN, DSCAM, SCN2A, TRIO | 1 | DYRK1A (MIM: 600855) | 0.04 | [1.05, inf] | 6.34 |

| d = 500 kb | 21 | ARID1B (2), CACNA1D (MIM: 114206), CHD2 (MIM: 602119), MYO1E (MIM: 601479), NR3C2, PRKAR1B, PRKCA, PYHIN1 (2; MIM: 612677), SCN2A, SHANK3, WDFY3, DSCAM, PRKAR1B, RFX7 (MIM: 612660), SCN2A, SLC6A13 (MIM: 615097), SRCAP (MIM: 611421), TRIO, UNC45B (MIM: 611220) | 9 | DYRK1A (3), TMEM94, CACNA1D, CHD2, CHD8 (MIM: 610528), RFX7, UNC45B | 0.08 | [0.91, inf] | 1.85 |

| d = 1 Mb | 28 | ARID1B (2), ASH1L (MIM: 607999), CACNA1D, CHD2, CREBBP (2; MIM: 600140), MYO1E, NR3C2, NRXN1 (MIM: 600565), POGZ (MIM: 614787), PRKAR1B, PRKCA, PYHIN1 (2), SCN2A, SHANK3, WDFY3, AGAP2, DSCAM, PRKAR1B, RFX7, SCN2A, SLC6A13, SRCAP, TRIO, UBE3C (MIM: 614454), UNC45B | 18 | CACNA1D, CHD2, CLASP1 (MIM: 605852), DYRK1A (3), TMEM94 (2), LAMC3, PSME4 (MIM: 607705), SCN2A, TBR1 (MIM: 604616), WDFY3, CHD8, RFX7, SRCAP, UBE3C, UNC45B | 0.3 | [0.72, inf] | 1.23 |

This table summarizes the counts of possible disruptive mutations (de novo SNVs or CNVs) in predicted regulatory regions between probands and unaffected (control) siblings. The analysis is limited to genes associated with autism risk according to previous evidence of de novo LGD mutations in the coding region. The nearest gene with a given distance (d) is indicated as described in the Material and Methods. Abbreviations are as follows: inf, infinity; and OR, odds ratio.

Table 2.

Variants of Interest in Autistic Individuals from 53 Families

| Genomic HGVS (GRCh37) | Individual | Inheritance | Valid | Caller | Dataset | Type | Gene Exonic Splice | Putative Regulatory Variant | RefSeq HGVS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChrX: g.154770750_154784551del | 11000.p1 | MP | Yˆ | VH | phase II | CDS | TMLHE | N |

NM_018196: c.–1–9613_181+4007del |

| Chr21: g.42016189_42030325del | 11572.p1 | MP | Y | D, GS, VH | phase I | NCS | N | DSCAM (d = 10 kb)∗ | – |

| Chr12: g.1948914_1984653del | 11709.p1 | FP | Y | GS, VH | phase II | CDS | CACNA2D4 | N |

NM_172364: c.1720–150_2551+991del |

| Chr6: g.157315964_157328116del | 11709.p1 | MP | Y | GS, VH | phase II | NCS | N | ARID1B (d = 10 kb)∗ | – |

| Chr2: g.166253120_166373394del | 11709.p1 | MP | Y | GS, VH | phase II | NCS | CSRNP3 | SCN2A (d = 10 kb)∗ | – |

| Chr1: g.231828151_231933482del | 11712.p1 | MP | Y | GS, VH | phase II | CDS | DISC1 | N |

NM_018662: c.68–1421_1690–2372del |

| Chr2: g.149051133_149086337del | 11712.p1 | FP | Y | GS, VH | phase II | NCS | N | MBD5 (d = 10 kb) | – |

| Chr2: g.233396326G>A | 11729.p1 | DN | Y | GATK | phase II | CDS missense | CHRND | N |

NM_000751: c.1007G>A; NP_000742: p.Arg336Gln |

| Chr11: g.67926275G>A | 11729.p1 | DN | Y | GATK | phase II | CDS missense | SUV420H1 | N |

NM_017635: c.1538C>T; NP_060105: p.Ala513Val |

| Chr3: g.178916936G>A | 11804.p1 | DN | Y | GATK | phase II | CDS missense | PIK3CA | N |

NM_006218: c.323G>A; NP_006209: p.Arg108His |

| Chr3: g.13920617_13922554del | 12793.p1 | MP | Y | GS,VH | phase I | CDS | WNT7A | N |

NM_004625: c.–1241_71+626del |

| Chr4: g.148986808G>A | 12793.p1 | DN | Y | GATK | phase I | NCS | N | NR3C2 (d = 25 kb)∗ | – |

| Chr10: g.114901076G>A | 13069.p1 | DN | Y | GATK, F | phase I | ESS | TCF7L2 | N |

NM_001146274: c.685+1G>A |

| Chr6: g.157401254C>A | 13111.p1 | DN | Y | GATK | phase II | NCS | N | ARID1B (d = 10 kb)∗ | – |

| Chr11: g.131345836_131583798del | 13122.p1 | FP | Y | GS, VH | phase II | NCS | LOC101929653 | NTM | – |

| Chr16: g.6908075_7079700del | 13122.p1 | MP | Y | GS, VH | phase II | NCS | N | RBFOX1 (d = 10 kb) | – |

| Chr5: g.14015350_14055499dup | 13539.p1 | MP | Y | D | phase I | NCS | N | TRIO (d = 100 kb)∗ | – |

| Chr5: g.122155926_122163623del | 13825.p1 | FP | ND | GS, VH | phase II | CDS | SNX2 | N |

NM_003100: c.1212+1208_1509+282del |

| Chr15: g.25088705_25117621del | 13825.p1 | FP | Y | GS, VH | phase II | CDS | SNRPN | N | NM_022805: c–13736_–578–14041del |

| Chr12: g.99020493T>C | 13825.p1 | DN | Y | GATK | phase II | CDS missense | IKBIP | N | NM_153687: c.349A>G; NP_710154: p.Met117Val |

| Chr19: g.47635921_47687660dup | 13874.p1 | DN | Y | D | phase I | CDS | SAE1 | N | NM_005500: c.98+1636_734–12830dup |

| Chr1: g.159038053T>C | 13942.p1 | DN | Y | GATK, F | phase I | NCS | N | PYHIN1 (d = 100 kb)∗ | – |

| Chr5: g.153030052G>A | 13951.p1 | DN | Y | GATK, F | phase I | CDS missense | GRIA1 | N | NM_000827: c.623G>A; NP_000818: p.Arg208His |

| Chr5: g.179122573_179128204del | 14153.p1 | DN | Y | GS, VH | phase I | CDS | CANX | N | – |

| Chr11: g.119148951G>A | 14153.p1 | DN | Y | GATK, F | phase I | CDS missense | CBL | N | NM_005188: c.1171G>A; NP_005179: p.Val391Ile |

| Chr5: g.175921055A>G | 14153.p1 | DN | Y | GATK, F | phase I | CDS missense | FAF2 | N | NM_014613: c.539A>G; NP_055428: p.Asp180Gly |

| Chr7: g.79840305A>G | 14370.p1 | DN | Y | GATK, F | phase I | CDS missense | GNAI1 | N | NM_002069: c.611A>G; NP_002060: p.Gln204Arg |

| Chr17: g.64410805C>T | 14637.p1 | DN | Y | GATK, F | phase I | NCS | N | PRKCA (d = 10 kb)∗ | – |

“Genomic HGVS” lists the genomic HGVS information for the variant. “Individual” is the individual ID of the person with the event. “Inheritance” indicates the inheritance (MP, mother to proband; FP, father to proband; or DN, de novo). “Valid” indicates whether the event was validated by orthogonal methods (Y, yes; ND, not determined; or ˆ, published previously). “Caller” is the variant-calling program that detected this event (D, dCGH; F, FreeBayes; GS, GenomeSTRiP; and/or VH, VariationHunter). “Dataset” indicates whether the individual was part of phase I or phase II genome families in this study. “Type” indicates the variant type (NCS, noncoding sequence [putative regulatory]; CDS, coding sequence; CDS missense, coding missense; or ESS, essential splice site). “Gene exonic splice” indicates the gene with the exonic or splice-site mutation (N, no). In the “putative regulatory variant” column, d refers to the minimal distance as defined in the Material and Methods, and an asterisk indicates that the variant is in a gene where an enrichment of de novo mutations has been identified in autism. “RefSeq HGVS” values were calculated with Alamut v.2.7.1. and are indicated for mRNA and protein where available.

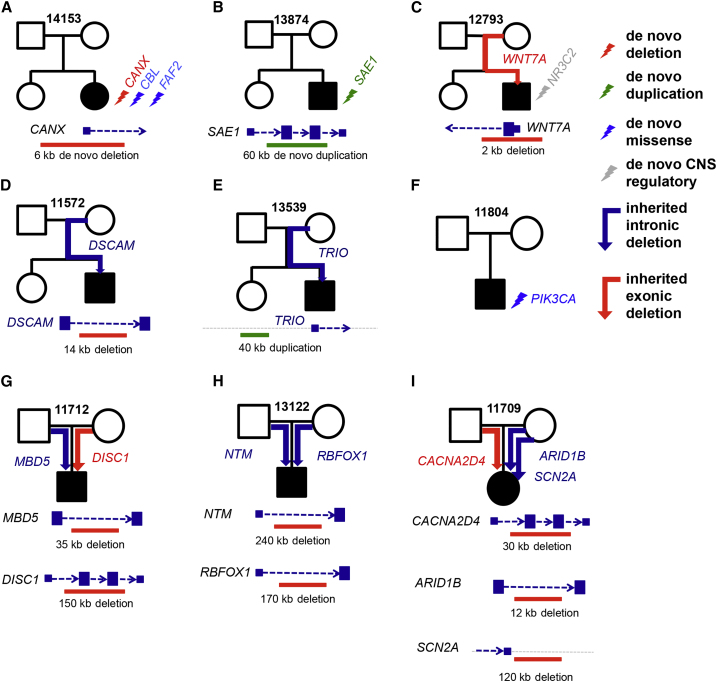

Figure 6.

All Variants Shown for Each Family Were Validated by Appropriate Methods

(A) Family 14153. The events are a de novo exonic deletion of the promoter and first exon of CANX and two de novo missense SNVs in CBL (MIM: 165360) and FAF2. The location of the de novo deletion is also shown with respect to CANX.

(B) Family 13874. The event is a de novo exonic duplication in SAE1. Furthermore, we provided a mock representation of the de novo duplication with respect to SAE1.

(C) Family 12793. The event is a promoter and exonic WNT7A deletion passed from the mother to the male proband. As shown in the mock representation of the inherited deletion, it removes the 5′ UTR and the first exon of WNT7A. This proband and the mother both have macrocephaly, which is in concordance with maternally inherited deletion of WNT7A.

(D) Family 11572. The event is a DSCAM deletion encompassing CNS DNase I hypersensitive sites passed from the mother to the male proband. This individual also suffers from nonfebrile seizures, in concordance with disruption of DSCAM.

(E) Family 13539. The event is a duplication upstream of TRIO. It encompasses CNS DNase I hypersensitive sites and was passed from the mother to the male proband.

(F) Family 11804. A conserved missense de novo mutation (phyloP = 2.57) was found in PIK3CA. This individual has macrocephaly, which is in concordance with disruption of PIK3CA.

(G) Family 11712. We found a maternally inherited rare, private exonic deletion of parts of DISC1 and a 35 kb paternally inherited rare intronic deletion of MBD5. The deletion affecting DISC1 is around 150 kb, deletes a few coding exons of this gene, and is not seen in over 15,000 genotyped control individuals.

(H) Family 13122. We found two large rare deletions that intersect NTM and RBFOX1—one inherited from the father and the other inherited from the mother. The maternally inherited rare deletion is 240 kb and deletes most of the first intron of NTM. This is an extremely rare deletion, given that it was not observed in over 15,000 control individuals. The paternally inherited rare deletion is 170 kb and deletes an intron of RBFOX1.

(I) Family 11709. We found three rare, private deletions affecting genes of interest. First, we found a 30 kb paternally inherited rare, private exonic deletion of CACNA2D4. We also found two maternally inherited rare, private deletions that affect genes of interest. One is a 120 kb exonic rare and private deletion less than 5 kb downstream of SCN2A, and the other is a 12 kb rare deletion of an intron of ARID1B.

Finally, we focused on integrating all potential disease-related CNV, SNV, and indel events in our set of 53 autism-affected families. In addition to identifying de novo and private mutations in putative regulatory elements of genes associated with autism risk, we identified and validated gene-disruptive CNVs in neurodevelopmental genes (DISC1 [MIM: 605210], WNT7A [MIM: 601570], RBFOX1 [MIM: 605104], and MBD5 [MIM: 611472]). We also validated smaller de novo CNVs and SNV exon-specific mutations missed by exome sequencing in likely candidate genes (e.g., CANX, SAE1, and PIK3CA [MIM: 171834]) according to the literature. The evidence and significance of each are discussed in detail below. Given that autism involves a well-appreciated sex bias favoring males, we considered the yield among four different proband-sibling gender combinations (male-male, male-female, female-male, and female-female) where applicable. In this analysis (Table S16), families were scored as having a candidate event in a gene associated with autism mutational burden, a candidate event in another gene, other events, or no events. Excluding two control families in whom potential pathogenic exonic events had been previously identified, we identified 16 families (31.3%) containing largely private or de novo events within genes previously associated with autism or neurodevelopmental disease; nine families (17.6%) in particular carried potentially high-impact variants (Figure 6). Among the latter, at least five probands (9.8%) were deemed to carry multiple high-impact variants, often as a result of transmission from both parents or of multiple de novo events.

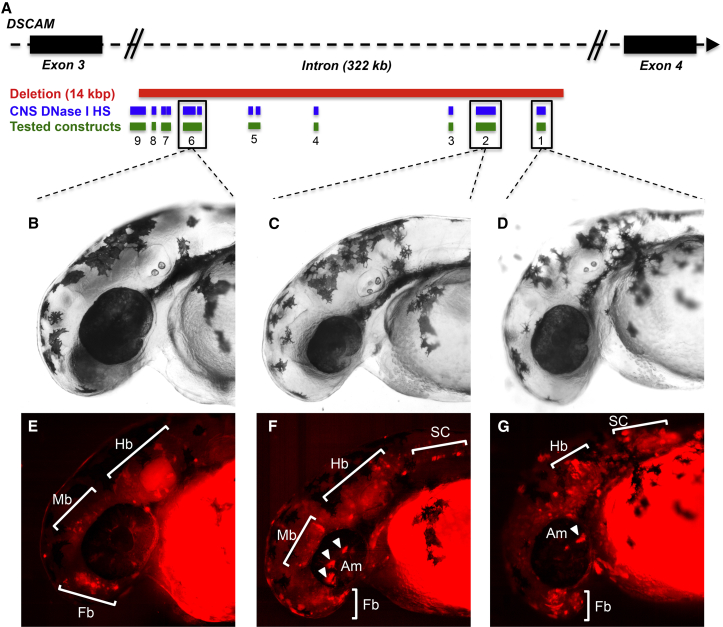

In Vivo Functional Testing of DSCAM Deletion Interval

Although DNase I hypersensitivity sites are enriched with noncoding regulatory DNA, their functional potential can only be determined through experimentation. We selected one of the smallest CNVs (14 kb DSCAM deletion interval from family 11572), which contained 12 CNS DNase I hypersensitivity sites, and assayed its potential to direct tissue-dependent reporter expression in a previously described transgenic zebrafish assay51, 52 (see Material and Methods). We synthesized nine sequence intervals (150–630 bp), corresponding to either one or two of the 12 CNS DNase I hypersensitive sites within the interval (Figure 7; see Material and Methods). Our analysis indicated that all nine constructs directed reporter expression in the CNS of 48 hpf G0 mosaic zebrafish embryos (Table 3). Although the lower threshold for reporting CNS positive expression only required signal to be detected in ≥20% of injected embryos, all constructs comfortably exceeded this threshold (range 49%–73%). Expression was seen consistently across a variety of CNS structures, including the forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain, spinal cord, olfactory placodes, and amacrine cells (Figure 7). We note that expression outside of the CNS was not consistently detected for any of the constructs, providing further evidence of the specificity. These findings are consistent with our hypothesis that the sequences within the 14 kb DSCAM deletion have regulatory potential that affects CNS biology. Analyses of reporter expression in stable transgenic lines will be needed for further validating this initial finding and refining our understanding of the neuronal populations in which these sequences can function.

Figure 7.

Functional Analysis of CNS DNase I Hypersensitivity Sites in the DSCAM Deletion

(A) Schematic of the 14 kb DSCAM deletion observed in family 11572. The diagram illustrates the 12 DNase I hypersensitivity sites (HSs) contained within the deletion, as well as the nine sequence intervals encompassing them. These sequence intervals were tested for their potential to direct reporter expression.

(B–D) Bright-field images of representative 48 hpf mosaic zebrafish embryos injected with DSCAM-6 (B), DSCAM-2 (C), and DSCAM-1 (D).

(E–G) tdTomato expression in representative 48 hpf mosaic embryos injected with DSCAM-6 (E), DSCAM-2 (F), and DSCAM-1 (G). Expression was seen in the forebrain (E–G), hindbrain (E–G), midbrain (E and F), spinal cord (F and G), and amacrine cells (F and G).

Table 3.

Number of Positive Mosaic Embryos per Zebrafish Assay

| Construct | Positive Mosaic Embryos | Structures with Expression |

|---|---|---|

| DSCAM-1 | 151/207 (73%) | Fb, Hb, Am, SC |

| DSCAM-2 | 129/211 (61%) | Fb, Mb, Hb, SC |

| DSCAM-3 | 127/214 (59%) | Fb, Mb, Hb |

| DSCAM-4 | 97/161 (60%) | Fb, Hb, Am, OP |

| DSCAM-5 | 118/180 (66%) | Fb, Hb, Am |

| DSCAM-6 | 80/162 (49%) | Fb, Mb, Hb, Am, SC |

| DSCAM-7 | 128/182 (72%) | Fb, Hb |

| DSCAM-8 | 125/174 (72%) | Fb |

| DSCAM-9 | 118/189 (62%) | Hb, SC |

Specific brain structures with expression are indicated. Abbreviations are as follows: Fb, forebrain; Mb, midbrain; Hb, hindbrain; Am, amacrine cells; SC, spinal cord; and OP, plfactory placode.

Discussion

In this study, we fully sequenced the genomes of 53 families who are affected by simplex autism and in whom de novo LGD mutations and large CNVs had not been detected by previous exome sequencing and microarray analysis. By this approach, we hypothesized that we would identify disease-associated events mapping to noncoding regions likely to affect gene regulation. We focused on de novo and rare inherited SNVs, indels, and CNVs identified with multiple callers in an effort to establish a set of best practices. It is critical to use a number of high-quality callers to detect variation given that no caller, at this time, is able to detect all relevant variants. In the case of SNVs, we applied both FreeBayes and GATK. The benefits of using multiple callers are twofold. First, when a variant is found by both callers, the VR is very high (89.1%), providing a very high-confidence set. Second, each caller is able to detect variants that the other missed. In our study of 40 quads, an additional 2,567 and 91 de novo and 133,058 and 57,974 private variant calls were detected by GATK alone and FreeBayes alone, respectively. These additional calls will be critical for discovering disease-related variants in affected individuals, although additional validation is required. For CNVs, especially, it is necessary to apply methods based on both read depth and read pairs. Similarly, implementing multiple de novo SNV callers significantly increases sensitivity. In this study, we combined the well-established practice of using a machine-learning-based approach to discover a high-quality dataset with the benefit of additional variants by a genotype likelihood-based approach.

In our study, we had access to WES and WGS data generated with the same sequencing platform for 149 of the individuals. This comparison differs from that of a previously published study of genome sequencing in intellectual disability,12 where the comparison was made with very different platforms (e.g., Complete Genomics WGS and SOLiD WES). On the basis of our comparisons of WGS and WES, we hypothesize that the heterogeneity in sequencing platforms most likely led to an overestimate of the utility of genome sequencing data, in part because the SOLiD data had much poorer representation of the exome (∼50% fewer variants than would be expected on the basis of more recent experiments).8, 13 In addition, the comparison presented here is more direct because we controlled for differences in discovery methods by calling SNVs and indels calls with the exact same software packages. Our study has found a benefit of using both WES and WGS for discovering SNVs and indels, as in a previously reported study,13 and highlights to a much greater extent the utility of CNV discovery within genome data and its superiority over exome sequencing in detecting variants. Although exome sequencing is very cost efficient, we found that genome sequencing increased sensitivity within protein-coding regions in that it recovered on average two million more bases than WES. In particular, this addition was in regions of higher GC content and allowed access to additional sequence in 1,854 genes previously missed in most samples by exome sequencing. SNV and indel calling was much more uniform in an analysis of genome sequencing data—the only noticeable shift in variation numbers was due to ancestry. Remarkably, the greatest benefit came from the discovery of small CNVs corresponding to single-exon events that cannot be reliably detected through exome sequence data.7 Importantly, these differences are in addition to the potential importance to be derived from the vastly increased sensitivity WGS provides over WES in analysis of noncoding transcribed and intergenic sequences. Nevertheless, combining both WES and WGS datasets achieves maximal sensitivity in discovering variants in coding DNA sequence (CDS). Our data suggest that integrating WES has the potential to increase SNV yield within protein-coding regions by 5%–10%, partly because of the higher sequence coverage afforded by WES. In lieu of combining WES and WGS, an alternate approach would be to perform deeper WGS sequencing,12 especially as the cost of WGS declines and WES is ultimately abandoned.

Among the de novo mutations in the 53 families, we discovered a 6 kb deletion of the first exon and promoter of calnexin (CANX) in proband 14153.p1. CANX binds calcium and associates with N-linked glycoproteins in the endoplasmic reticulum, where it is thought to function as a molecular chaperone. The gene is highly expressed in human neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells59 and has been predicted to be a protein-protein interaction hub associated with de novo mutations in individuals with schizophrenia.60 Interestingly, this particular affected female individual has the highest burden of de novo mutations (n = 3) in this study and might be an example of the female protective effect, whereby the development of autism requires a higher genetic burden.61, 62 In another family (13874), we discovered a larger de novo duplication (52 kb) affecting multiple exons of SUMO-activating enzyme unit 1, SAE1. SAE1 encodes one of the key proteins associated with the sumoylation pathway,63 which plays a role, among many others, in neuronal differentiation and synapse formation.64 Remarkably, four additional individuals carrying duplications of this locus have been reported previously in autism,65, 66 suggesting that a recurrent duplication might be associated with autism risk (Figure S16). We also discovered de novo missense mutations in genes associated with the glutamate receptor excitatory pathway in proband 13951.p1 (GRIA1 [MIM: 138248]) and proband 14370.p1 (GNAI1 [MIM: 139310]), as well as de novo mutations in two genes (CHRND [MIM: 100720] and SUV420H1 [MIM: 610881]) in proband 11729.p1 and a severe missense mutation (c.323G>A [p.Arg108His]) in the first exon of PIK3CA, missed by exome sequencing, in proband 11804.p1. Missense mutations of this gene have been previously associated with megalencephaly-capillary malformation-polymicrogyria (MCAP syndrome [MIM: 602501]),67 megalencephaly, hemimegalencephaly, and focal cortical dysplasia.68, 69 The autistic proband in this case was macrocephalic with a head circumference of 62 cm (5.6 SDs above the mean70) and a height of 147 cm (age 10 years).

Among potential inherited risk variants, we discovered that a private deletion of the promoter and first exon of WNT7A was transmitted maternally to a male proband (12793.p1). This CNV was only detected by read-pair analysis and was probably missed by WES because of its size (2 kb) and very high GC content (∼79%). WGS read-depth analysis, SNP microarray, and aCGH validation failed to detect or validate this event. PCR and sequencing of the breakpoints were the only experimental methods that confirmed the deletion. WNT7A is a critical gene in both cell proliferation and Wnt signaling; it has been implicated in diverse neuronal processes, including neural stem cell renewal, synapse formation, axon guidance, and neuronal progenitor cell progression.71 Whereas only the proband has a diagnosis of autism, both the proband and his mother have macrocephaly, and the proband has complications of gastrointestinal dysfunction—phenotypes seen in other genes associated with Wnt signaling.72 We also identified that a small deletion (14 kb) within noncoding putative regulatory DNA of DSCAM was transmitted from the mother to the male proband in family 11572. DSCAM is one of two genes associated with neurocognitive dysfunction with Down syndrome (MIM: 190685), and multiple de novo and inherited CNVs disrupting this gene have been reported among cases of autism.7, 45 For this particular deletion, 19% of the locus is characterized as DNase I hypersensitive, representing open chromatin; we hypothesize that the deletion is likely to have an effect on gene regulation. The proband in this family has a history of seizures—a phenotype also found in mice homozygous for loss-of-function mutations in this gene.73 In addition, our modeling in zebrafish showed that nine of nine tested CNS DNase I hypersensitive sites drive expression in vivo in the CNS (Figure 7 and Figure S17). We also found that a 40 kb noncoding putative regulatory duplication upstream of the gene TRIO was transmitted from the mother to the male proband in family 13539. TRIO encodes a rho-guanine nucleotide exchange factor and has been observed to be disrupted by new mutations in children with autism and intellectual disability.57, 74 Although this deletion does not affect exons, we note that 8% of the locus is DNase I hypersensitive and carries a robust H3K27AC signal, demarcating active regulatory elements.10 Although validating the effect of these smaller CNVs will require additional functional work, the association between such private or de novo damaging events and genes already implicated in autism makes them particularly appealing candidates. Most of the smaller CNVs associated with autism risk in this study were transmitted from the mother to the male proband, consistent with the maternal transmission bias observed for large CNVs and now inherited private gene-disruptive SNVs in autism.7, 61, 75

In five (∼10%) families, we identified probands carrying multiple high-risk mutations, potentially consistent with a more complex oligogenic model of autism risk.76 Autism proband 11712.p1, for example, carries a maternally inherited 120 kb genic deletion of DISC1, a gene strongly associated with schizophrenia (MIM: 181500) and bipolar disorder (MIM: 125480)77, 78—as well as a 35 kb paternally inherited private intronic deletion of MBD5 (MIM: 611472), a gene previously implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders.79, 80 In male proband 13122.p1, we identified two large private CNVs within the introns of neurodevelopmental genes NTM (MIM: 607938)81) and RBFOX182, 83, 84 (Figure 6). One female autistic proband, 13825.p1, carries a de novo missense mutation in IKBIP (MIM: 609861), in addition to a maternally inherited deletion of SNX2 (MIM: 605929) and paternally inherited 29 kb deletion involving a portion of the 5′ UTR of SNRPN (MIM: 182279), a maternal imprinted gene associated with Prader-Willi syndrome.85 In another female proband, 11709.p1, we found three rare, private deletions affecting neurodevelopmental genes. These include two maternally inherited deletions, a 12 kb intronic deletion of ARID1B, and a 120 kb deletion mapping within 5 kb of SCN2A, as well as a 30 kb paternally inherited rare exonic deletion of CACNA2D4 (MIM: 608171). The latter CNV is significantly more abundant in individuals with pediatric developmental delay and autism spectrum disorders than in control individuals (OR = 2.75, p = 0.03).43 These findings suggest that smaller CNVs affecting single exons and regulatory elements in genes associated with dosage imbalance and autism risk will be an important area of focus for future investigation.

Conflicts of Interest

E.E.E. is on the scientific advisory board of DNAnexus Inc. and is a consultant for Kunming University of Science and Technology as part of the 1000 China Talent Program.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Brown for assistance in editing this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Simons Foundation (SFARI 336475 to E.E.E.), National Institute of Child Health and Development (HHSN267200700021C to J.M.S.), (HHSN275200800015C and HHSN267200700023C to E.M.F.), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS062972 to A.S.M.), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (predoctoral training grant 5T32GM07814 to P.W.H.), and National Human Genome Research Institute (postdoctoral training grant 2T32HG000035 to T.N.T.). We also thank Dr. Daniela Witten for advice on statistical testing of regulatory elements and Dr. Bradley Coe for information on CNVs from his previous publication. We thank Natalia Volfovsky, Alex Lash, and Malcolm Mallardi from the Simons Foundation for help with depositing genome data to SFARI Base and Colleen Davis for help with depositing genome data to dbGaP. We are grateful to all of the families at the participating Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) sites, as well as the principal investigators (A. Beaudet, R. Bernier, J. Constantino, E. Cook, E. Fombonne, D. Geschwind, R. Goin-Kochel, E. Hanson, D. Grice, A. Klin, D. Ledbetter, C. Lord, C. Martin, D. Martin, R. Maxim, J. Miles, O. Ousley, K. Pelphrey, B. Peterson, J. Piggot, C. Saulnier, M. State, W. Stone, J. Sutcliffe, C. Walsh, Z. Warren, and E. Wijsman). We appreciate receiving access to phenotypic data on Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) Base. Approved researchers can obtain the SSC population dataset described in this study by applying at SFARI Base (see Web Resources). E.E.E. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Published: December 31, 2015

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include 17 figures and 16 tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.11.023.

Accession Numbers

The accession number for the phase I genome sequences reported in this paper is SFARI Base: SFARI_SSC_WGS_P. The accession numbers for the phase II genome sequences are SFARI Base: SFARI_SSC_WGS_trioP and dbGaP: phs001035. The variant calls reported in this paper are available in the National Database for Autism Research under accession number NDAR: 10.15154/1226523.

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

1000 Genomes GRCh37 assembly, ftp://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/technical/reference/human_g1k_v37.fasta.gz

National Database for Autism Research (NDAR) study, http://dx.doi.org/10.15154/1226523

OMIM, http://www.omim.org

SFARI Base, https://base.sfari.org/

SFARI Base WGS data, https://sfari.org/resources/autism-cohorts/simons-simplex-collection

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Steffenburg S., Gillberg C., Hellgren L., Andersson L., Gillberg I.C., Jakobsson G., Bohman M. A twin study of autism in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 1989;30:405–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey A., Le Couteur A., Gottesman I., Bolton P., Simonoff E., Yuzda E., Rutter M. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol. Med. 1995;25:63–77. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verkerk A.J., Pieretti M., Sutcliffe J.S., Fu Y.H., Kuhl D.P., Pizzuti A., Reiner O., Richards S., Victoria M.F., Zhang F.P. Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 1991;65:905–914. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90397-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amir R.E., Van den Veyver I.B., Wan M., Tran C.Q., Francke U., Zoghbi H.Y. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iossifov I., O’Roak B.J., Sanders S.J., Ronemus M., Krumm N., Levy D., Stessman H.A., Witherspoon K.T., Vives L., Patterson K.E. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2014;515:216–221. doi: 10.1038/nature13908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrovski S., Wang Q., Heinzen E.L., Allen A.S., Goldstein D.B. Genic intolerance to functional variation and the interpretation of personal genomes. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krumm N., Turner T.N., Baker C., Vives L., Mohajeri K., Witherspoon K., Raja A., Coe B.P., Stessman H.A., He Z.X. Excess of rare, inherited truncating mutations in autism. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:582–588. doi: 10.1038/ng.3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuen R.K., Thiruvahindrapuram B., Merico D., Walker S., Tammimies K., Hoang N., Chrysler C., Nalpathamkalam T., Pellecchia G., Liu Y. Whole-genome sequencing of quartet families with autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Med. 2015;21:185–191. doi: 10.1038/nm.3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas D.J., Rosenbloom K.R., Clawson H., Hinrichs A.S., Trumbower H., Raney B.J., Karolchik D., Barber G.P., Harte R.A., Hillman-Jackson J., ENCODE Project Consortium The ENCODE Project at UC Santa Cruz. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D663–D667. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ENCODE Project Consortium The ENCODE (ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) Project. Science. 2004;306:636–640. doi: 10.1126/science.1105136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lettice L.A., Heaney S.J., Purdie L.A., Li L., de Beer P., Oostra B.A., Goode D., Elgar G., Hill R.E., de Graaff E. A long-range Shh enhancer regulates expression in the developing limb and fin and is associated with preaxial polydactyly. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:1725–1735. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilissen C., Hehir-Kwa J.Y., Thung D.T., van de Vorst M., van Bon B.W., Willemsen M.H., Kwint M., Janssen I.M., Hoischen A., Schenck A. Genome sequencing identifies major causes of severe intellectual disability. Nature. 2014;511:344–347. doi: 10.1038/nature13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belkadi A., Bolze A., Itan Y., Cobat A., Vincent Q.B., Antipenko A., Shang L., Boisson B., Casanova J.-L., Abel L. Whole-genome sequencing is more powerful than whole-exome sequencing for detecting exome variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:5473–5478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418631112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lelieveld S.H., Spielmann M., Mundlos S., Veltman J.A., Gilissen C. Comparison of Exome and Genome Sequencing Technologies for the Complete Capture of Protein-Coding Regions. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:815–822. doi: 10.1002/humu.22813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iossifov I., Ronemus M., Levy D., Wang Z., Hakker I., Rosenbaum J., Yamrom B., Lee Y.H., Narzisi G., Leotta A. De novo gene disruptions in children on the autistic spectrum. Neuron. 2012;74:285–299. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanders S.J., Murtha M.T., Gupta A.R., Murdoch J.D., Raubeson M.J., Willsey A.J., Ercan-Sencicek A.G., DiLullo N.M., Parikshak N.N., Stein J.L. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature. 2012;485:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Roak B.J., Deriziotis P., Lee C., Vives L., Schwartz J.J., Girirajan S., Karakoc E., Mackenzie A.P., Ng S.B., Baker C. Exome sequencing in sporadic autism spectrum disorders identifies severe de novo mutations. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:585–589. doi: 10.1038/ng.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Roak B.J., Vives L., Girirajan S., Karakoc E., Krumm N., Coe B.P., Levy R., Ko A., Lee C., Smith J.D. Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature. 2012;485:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanders S.J., Ercan-Sencicek A.G., Hus V., Luo R., Murtha M.T., Moreno-De-Luca D., Chu S.H., Moreau M.P., Gupta A.R., Thomson S.A. Multiple recurrent de novo CNVs, including duplications of the 7q11.23 Williams syndrome region, are strongly associated with autism. Neuron. 2011;70:863–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy D., Ronemus M., Yamrom B., Lee Y.H., Leotta A., Kendall J., Marks S., Lakshmi B., Pai D., Ye K. Rare de novo and transmitted copy-number variation in autistic spectrum disorders. Neuron. 2011;70:886–897. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hach F., Hormozdiari F., Alkan C., Hormozdiari F., Birol I., Eichler E.E., Sahinalp S.C. mrsFAST: a cache-oblivious algorithm for short-read mapping. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:576–577. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0810-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manichaikul A., Mychaleckyj J.C., Rich S.S., Daly K., Sale M., Chen W.M. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2867–2873. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girirajan S., Brkanac Z., Coe B.P., Baker C., Vives L., Vu T.H., Shafer N., Bernier R., Ferrero G.B., Silengo M. Relative burden of large CNVs on a range of neurodevelopmental phenotypes. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Celestino-Soper P.B., Shaw C.A., Sanders S.J., Li J., Murtha M.T., Ercan-Sencicek A.G., Davis L., Thomson S., Gambin T., Chinault A.C. Use of array CGH to detect exonic copy number variants throughout the genome in autism families detects a novel deletion in TMLHE. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:4360–4370. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A., Garimella K., Altshuler D., Gabriel S., Daly M., DePristo M.A. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van der Auwera G.A., Carneiro M.O., Hartl C., Poplin R., Del Angel G., Levy-Moonshine A., Jordan T., Shakir K., Roazen D., Thibault J. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2013;11:11.10.11–11.10.33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garrison, E.M.G. (2012). Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. arXiv, arXiv:1207.3907, http://arxiv.org/abs/1207.3907.

- 28.Rimmer A., Phan H., Mathieson I., Iqbal Z., Twigg S.R., Wilkie A.O., McVean G., Lunter G., WGS500 Consortium Integrating mapping-, assembly- and haplotype-based approaches for calling variants in clinical sequencing applications. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:912–918. doi: 10.1038/ng.3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y., Li B., Tan R., Zhu X., Wang Y. A gradient-boosting approach for filtering de novo mutations in parent-offspring trios. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1830–1836. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei Q., Zhan X., Zhong X., Liu Y., Han Y., Chen W., Li B. A Bayesian framework for de novo mutation calling in parents-offspring trios. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1375–1381. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Roak B.J., Vives L., Fu W., Egertson J.D., Stanaway I.B., Phelps I.G., Carvill G., Kumar A., Lee C., Ankenman K. Multiplex targeted sequencing identifies recurrently mutated genes in autism spectrum disorders. Science. 2012;338:1619–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.1227764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson J.T., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Winckler W., Guttman M., Lander E.S., Getz G., Mesirov J.P. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michaelson J.J., Shi Y., Gujral M., Zheng H., Malhotra D., Jin X., Jian M., Liu G., Greer D., Bhandari A. Whole-genome sequencing in autism identifies hot spots for de novo germline mutation. Cell. 2012;151:1431–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng S.B., Turner E.H., Robertson P.D., Flygare S.D., Bigham A.W., Lee C., Shaffer T., Wong M., Bhattacharjee A., Eichler E.E. Targeted capture and massively parallel sequencing of 12 human exomes. Nature. 2009;461:272–276. doi: 10.1038/nature08250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sudmant P.H., Kitzman J.O., Antonacci F., Alkan C., Malig M., Tsalenko A., Sampas N., Bruhn L., Shendure J., Eichler E.E., 1000 Genomes Project Diversity of human copy number variation and multicopy genes. Science. 2010;330:641–646. doi: 10.1126/science.1197005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Handsaker R.E., Korn J.M., Nemesh J., McCarroll S.A. Discovery and genotyping of genome structural polymorphism by sequencing on a population scale. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:269–276. doi: 10.1038/ng.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hormozdiari F., Hajirasouliha I., McPherson A., Eichler E.E., Sahinalp S.C. Simultaneous structural variation discovery among multiple paired-end sequenced genomes. Genome Res. 2011;21:2203–2212. doi: 10.1101/gr.120501.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fromer M., Moran J.L., Chambert K., Banks E., Bergen S.E., Ruderfer D.M., Handsaker R.E., McCarroll S.A., O’Donovan M.C., Owen M.J. Discovery and statistical genotyping of copy-number variation from whole-exome sequencing depth. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krumm N., Sudmant P.H., Ko A., O’Roak B.J., Malig M., Coe B.P., Quinlan A.R., Nickerson D.A., Eichler E.E., NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project Copy number variation detection and genotyping from exome sequence data. Genome Res. 2012;22:1525–1532. doi: 10.1101/gr.138115.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Münz M., Ruark E., Renwick A., Ramsay E., Clarke M., Mahamdallie S., Cloke V., Seal S., Strydom A., Lunter G., Rahman N. CSN and CAVA: variant annotation tools for rapid, robust next-generation sequencing analysis in the clinical setting. Genome Med. 2015;7:76. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0195-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sherry S.T., Ward M., Sirotkin K. dbSNP-database for single nucleotide polymorphisms and other classes of minor genetic variation. Genome Res. 1999;9:677–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coe B.P., Witherspoon K., Rosenfeld J.A., van Bon B.W., Vulto-van Silfhout A.T., Bosco P., Friend K.L., Baker C., Buono S., Vissers L.E. Refining analyses of copy number variation identifies specific genes associated with developmental delay. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:1063–1071. doi: 10.1038/ng.3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.John S., Sabo P.J., Thurman R.E., Sung M.H., Biddie S.C., Johnson T.A., Hager G.L., Stamatoyannopoulos J.A. Chromatin accessibility pre-determines glucocorticoid receptor binding patterns. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:264–268. doi: 10.1038/ng.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Roak B.J., Stessman H.A., Boyle E.A., Witherspoon K.T., Martin B., Lee C., Vives L., Baker C., Hiatt J.B., Nickerson D.A. Recurrent de novo mutations implicate novel genes underlying simplex autism risk. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5595. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liaw A., Wiener M. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News. 2002;2:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hothorn T., Hornik K., Zeileis A. Unbiased Recursive Partitioning: A Conditional Inference Framework. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2006;15:651–674. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ritchie M.E., Carvalho B.S., Hetrick K.N., Tavaré S., Irizarry R.A. R/Bioconductor software for Illumina’s Infinium whole-genome genotyping BeadChips. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2621–2623. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scharpf R.B., Irizarry R.A., Ritchie M.E., Carvalho B., Ruczinski I. Using the R Package crlmm for Genotyping and Copy Number Estimation. J. Stat. Softw. 2011;40:1–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fu C., Wehr D.R., Edwards J., Hauge B. Rapid one-step recombinational cloning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fisher S., Grice E.A., Vinton R.M., Bessling S.L., McCallion A.S. Conservation of RET regulatory function from human to zebrafish without sequence similarity. Science. 2006;312:276–279. doi: 10.1126/science.1124070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fisher S., Grice E.A., Vinton R.M., Bessling S.L., Urasaki A., Kawakami K., McCallion A.S. Evaluating the biological relevance of putative enhancers using Tol2 transposon-mediated transgenesis in zebrafish. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1297–1305. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kimmel C.B., Ballard W.W., Kimmel S.R., Ullmann B., Schilling T.F. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitlock K.E., Westerfield M. The olfactory placodes of the zebrafish form by convergence of cellular fields at the edge of the neural plate. Development. 2000;127:3645–3653. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.17.3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kong A., Frigge M.L., Masson G., Besenbacher S., Sulem P., Magnusson G., Gudjonsson S.A., Sigurdsson A., Jonasdottir A., Jonasdottir A. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father’s age to disease risk. Nature. 2012;488:471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature11396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meynert A.M., Ansari M., FitzPatrick D.R., Taylor M.S. Variant detection sensitivity and biases in whole genome and exome sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:247. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Rubeis S., He X., Goldberg A.P., Poultney C.S., Samocha K., Cicek A.E., Kou Y., Liu L., Fromer M., Walker S., DDD Study. Homozygosity Mapping Collaborative for Autism. UK10K Consortium Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature. 2014;515:209–215. doi: 10.1038/nature13772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Kok Y.J., Merkx G.F., van der Maarel S.M., Huber I., Malcolm S., Ropers H.H., Cremers F.P. A duplication/paracentric inversion associated with familial X-linked deafness (DFN3) suggests the presence of a regulatory element more than 400 kb upstream of the POU3F4 gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995;4:2145–2150. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin M., Pedrosa E., Shah A., Hrabovsky A., Maqbool S., Zheng D., Lachman H.M. RNA-Seq of human neurons derived from iPS cells reveals candidate long non-coding RNAs involved in neurogenesis and neuropsychiatric disorders. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu B., Ionita-Laza I., Roos J.L., Boone B., Woodrick S., Sun Y., Levy S., Gogos J.A., Karayiorgou M. De novo gene mutations highlight patterns of genetic and neural complexity in schizophrenia. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1365–1369. doi: 10.1038/ng.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jacquemont S., Coe B.P., Hersch M., Duyzend M.H., Krumm N., Bergmann S., Beckmann J.S., Rosenfeld J.A., Eichler E.E. A higher mutational burden in females supports a “female protective model” in neurodevelopmental disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;94:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Turner T.N., Sharma K., Oh E.C., Liu Y.P., Collins R.L., Sosa M.X., Auer D.R., Brand H., Sanders S.J., Moreno-De-Luca D. Loss of δ-catenin function in severe autism. Nature. 2015;520:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature14186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Okuma T., Honda R., Ichikawa G., Tsumagari N., Yasuda H. In vitro SUMO-1 modification requires two enzymatic steps, E1 and E2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;254:693–698. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Henley J.M., Craig T.J., Wilkinson K.A. Neuronal SUMOylation: mechanisms, physiology, and roles in neuronal dysfunction. Physiol. Rev. 2014;94:1249–1285. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lionel A.C., Crosbie J., Barbosa N., Goodale T., Thiruvahindrapuram B., Rickaby J., Gazzellone M., Carson A.R., Howe J.L., Wang Z. Rare copy number variation discovery and cross-disorder comparisons identify risk genes for ADHD. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:95ra75. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Prasad A., Merico D., Thiruvahindrapuram B., Wei J., Lionel A.C., Sato D., Rickaby J., Lu C., Szatmari P., Roberts W. A discovery resource of rare copy number variations in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. G3 (Bethesda) 2012;2:1665–1685. doi: 10.1534/g3.112.004689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rivière J.B., Mirzaa G.M., O’Roak B.J., Beddaoui M., Alcantara D., Conway R.L., St-Onge J., Schwartzentruber J.A., Gripp K.W., Nikkel S.M., Finding of Rare Disease Genes (FORGE) Canada Consortium De novo germline and postzygotic mutations in AKT3, PIK3R2 and PIK3CA cause a spectrum of related megalencephaly syndromes. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:934–940. doi: 10.1038/ng.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jansen L.A., Mirzaa G.M., Ishak G.E., O’Roak B.J., Hiatt J.B., Roden W.H., Gunter S.A., Christian S.L., Collins S., Adams C. PI3K/AKT pathway mutations cause a spectrum of brain malformations from megalencephaly to focal cortical dysplasia. Brain. 2015;138:1613–1628. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oda K., Okada J., Timmerman L., Rodriguez-Viciana P., Stokoe D., Shoji K., Taketani Y., Kuramoto H., Knight Z.A., Shokat K.M., McCormick F. PIK3CA cooperates with other phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase pathway mutations to effect oncogenic transformation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8127–8136. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roche A.F., Mukherjee D., Guo S.M., Moore W.M. Head circumference reference data: birth to 18 years. Pediatrics. 1987;79:706–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]