Abstract

Since the implementation of effective combination antiretroviral therapy, HIV infection has been transformed from a life-threatening condition into a chronic disease. As people with HIV are living longer, aging and its associated manifestations have become key priorities as part of HIV care. For women with HIV, menopause is an important part of aging to consider. Women currently represent more than one half of HIV-positive individuals worldwide. Given the vast proportion of women living with HIV who are, and will be, transitioning through age-related life events, the interaction between HIV infection and menopause must be addressed by clinicians and researchers. Menopause is a major clinical event that is universally experienced by women, but affects each individual woman uniquely. This transitional time in women’s lives has various clinical implications including physical and psychological symptoms, and accelerated development and progression of other age-related comorbidities, particularly cardiovascular disease, neurocognitive dysfunction, and bone mineral disease; all of which are potentially heightened by HIV or its treatment. Furthermore, within the context of HIV, there are the additional considerations of HIV acquisition and transmission risk, progression of infection, changes in antiretroviral pharmacokinetics, response, and toxicities. These menopausal manifestations and complications must be managed concurrently with HIV, while keeping in mind the potential influence of menopause on the prognosis of HIV infection itself. This results in additional complexity for clinicians caring for women living with HIV, and highlights the shifting paradigm in HIV care that must accompany this aging and evolving population.

Keywords: HIV, women, aging, menopause

Introduction

The nature of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pandemic has changed dramatically since discovered over 33 years ago. Extraordinary progress has been achieved in the management of HIV with the advent of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), which can effectively control viral replication, and has resulted in remarkable reductions in HIV-associated morbidity and mortality.1–4 In today’s landscape, the reported life expectancy for a person newly diagnosed with HIV, in the context of access to cART, can approach that of the general population.5 One of the greatest medical victories of this generation has been the transformation of HIV from an acute, life-limiting infection to a chronic disease with incredibly effective treatment.2

In addition to the marked changes in morbidity and life expectancy, the evolving epidemiology of HIV infection has seen an escalating impact on women. Current data suggest that of the 35 million people living with HIV worldwide, 52% are women. The proportion of infected women varies geographically:6 in Sub-Saharan Africa, women represent approximately 57% of those with HIV,6 while in developed countries such as Canada and the USA, this proportion is markedly lower at 22% to 23%.7,8 The vulnerability that women experience related to HIV, with respect to both the causes and consequences of infection, is a complex phenomenon resulting from biological and sociopolitical inequities.6,7

In earlier stages of the pandemic, the principal concerns surrounding HIV infection in women centered on sexual and reproductive health, largely due to the high rates of HIV infection among women of reproductive age and the risks of vertical transmission. However, in the current era of increasingly accessible and efficacious cART, and longer life expectancies, HIV in the context of increased age becomes a key clinical consideration.9,10 In 2011, 26% of individuals living with HIV in the USA were greater than 55 years of age.11 It is anticipated that by 2020, up to 70% of HIV infection will be in patients over the age of 70 years.12 Five percent of new infections in the USA are estimated to occur in those greater than 55 years of age, and older Americans are more likely to present in later stages of the disease.11 Consequently, issues pertaining to age-related comorbidities and other life events, including menopause, represent an emerging aspect of HIV care.9,13

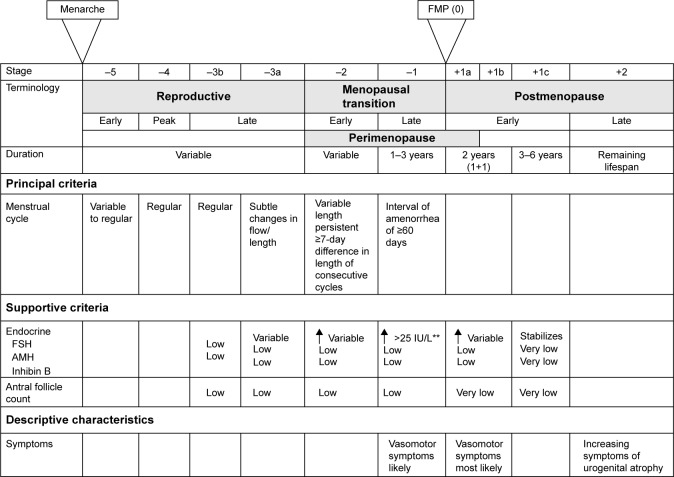

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines natural menopause as the permanent cessation of menses. Specifically, this refers to a period of amenorrhea of at least 12 months that is due to the loss of ovarian follicular activity, and occurs in the absence of any other physiologic or pathologic process.14,15 This is in contrast to other forms of menopause, in which an alternative etiology can be identified (Table 1).15 Natural menopause typically occurs between the ages of 50 and 52 years in developed nations, but there is considerable geographic variation with respect to age of onset throughout the world.16–20 As hormone production in the ovaries declines with age, and eventually ceases entirely, the menopausal transition occurs in three stages (Figure 1).21 Menopause is a complex clinical process that is uniquely experienced by each woman, and is associated with various biological and psychosocial changes including alterations in bone health, cognition, risk of other age-related comorbidities, and an array of physical and psychological symptoms.13,22–27 Women around the world from various cultural groups, races, and religions have been found to report diverse biological, sociocultural, and psychological factors that influence their experiences and perceptions related to menopause.23,28,29 In women living with HIV, an intricate relationship between HIV and menopause appears to exist in that HIV may influence the natural history, experience, and complications of menopause, while menopause itself could potentially influence the course of HIV infection.28 This bidirectional relationship between HIV infection and menopause confers an additional layer of complexity to the ongoing management of HIV-infected women as they age, and presents new and vaguely understood challenges for clinicians.

Table 1.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Natural menopause | Permanent cessation of menstruation resulting from a loss of ovarian follicular activity; diagnosis is made retrospectively after 12 months of amenorrhea in the absence of any other pathological or physiological cause |

| Perimenopause | The period immediately prior to menopause, when the endocrinological, biological, and clinical features of approaching menopause commence, and the first year after menopause |

| Premature menopause (or premature ovarian failure) | Menopause that occurs at an age less than two standard deviations below the mean established for the reference population; generally, refers to menopause prior to the age of 40 years |

| Induced menopause | Cessation of menstruation that follows either surgical removal of both ovaries (with or without hysterectomy) or iatrogenic ablation of ovarian function (including chemotherapy or radiation therapy) |

Figure 1.

The stages of the menopausal transition in women.

Notes: **Approximate expected level based on assays using current international pituitary standard. From Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop +10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Menopause. 2012;19(4):387–395.21 With permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Copyright ©2012.

Abbreviations: FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; FMP, final menstrual period; AMH, anti-Mullerian hormone.

Impact of menopause on HIV infection

Aging, menopause, and transmission of HIV

As individuals age, they continue to represent an important, but often overlooked, population at risk of acquiring HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).11,30 This has implications both from an individual and public health perspective. In 2010, approximately 5% of new HIV diagnoses in the USA occurred in adults greater than 55 years of age.11 Furthermore, older adults diagnosed with HIV tend to be diagnosed later on in the course of their disease, which can affect severity of immune dysfunction, response to treatment, and survival.11,31–34 In the USA in 2013, 27% of AIDS diagnoses, the most advanced stage of HIV infection,35 occurred in patients greater than 50 years of age.11 Additionally, while 98% of patients diagnosed with HIV between the ages of 20–29 years in the USA will survive beyond 12 months, the prognosis for new diagnoses in older adults is substantially lower. The proportion of those who survive for more than 1 year after diagnosis declines with increasing age, from 86% among those diagnosed at ages 50–59 years, to 82% among those aged 60–64 years, and 73% in those diagnosed at age 65 years and older.11

The primary mode of HIV transmission and acquisition in people over the age of 50 years is through sexual contact.11 While sexual activity does decline with age, many older individuals will continue to remain sexually active after the age of 50 years.11,30,36–38 In an assessment of sexual behavior in adults in the USA, 59% of women aged 55–59 years had engaged in sexual activity in the past year.30,39 A similar study of adults over the age of 60 years in the USA found that 71% of men and 51% of women remained sexually active.30,40 Furthermore, 30% of women in their 70s and 20% of those in their 80s engaged in some measure of sexual activity.30,40 Older adults will report sexual activity regardless of marital status, and may continue to engage in diverse sexual activities including vaginal-penile intercourse, oral sex, and receptive and insertive anal intercourse.30,39–42 These individuals, therefore, retain traditional risk factors for HIV acquisition. Condom use is an effective measure to prevent sexual transmission of HIV. However, with reduced fertility in the later years, condom use has been found to decline.43–46 The lack of condom use in older adults may be further explained by the misperception that they are at minimal risk of contracting HIV and other STIs.37,47 In fact, in an analysis of responses from 12,366 adults aged 50 years and older in the 2009 National Health Interview Survey in the USA, 84.1% believed they had zero chance of becoming infected with HIV.47 This underestimation of HIV-acquisition risk in older patients also extends to their physicians.11,37,48–50 For example, one study demonstrated that among individuals aged 58–93 years, of whom 57% were sexually active after the age of 60 years, 11% had received STI/HIV counselling from their physicians, and only 4% had ever been offered an HIV test.37 For postmenopausal women specifically, physiologic changes such as vaginal dryness, vaginal atrophy, and decreased libido likely contribute to reduced sexual activity. However, these changes in vaginal tissue may also increase biologic predisposition to acquiring HIV infection, even with reduced sexual contact.6,9,11,51,52 Therefore, it is important that physicians and other health care providers continue to discuss sexual behaviors with their aging patients, and counsel them on strategies to prevent HIV and other STIs. It is equally critical that HIV testing be offered to older adults who remain sexually active.

Continuation of sexual activity into older age has also been demonstrated in the HIV-positive population.32,36,53 In an assessment of women aged 40–57 years in the Women’s Interagency Health Study (WIHS), a prospective cohort study of HIV-positive and -negative women in the USA, 73%–74% of HIV-positive women remained sexually active.36 This included women with detectable and undetectable viral loads.36 With increasing age, there were similar patterns of reduced sexual activity between sero-positive and sero-negative women in the cohort.36 Similarly, a study of 123 HIV-positive women over the age of 50 years in the UK found that 60% remained sexually active.32 Unfortunately, up to one-third of older, HIV-infected patients report having unprotected intercourse, including with serodiscordant partners.36,53 While limited reproductive potential and underestimation of STI acquisition risk have been postulated as the reasons for low condom use in older adults, additional factors among people with HIV, including fear of HIV-related stigma and forced disclosure of HIV status, may also contribute to suboptimal condom use.11,43,44,54–56 Studies exploring condom use among postmenopausal women with HIV have suggested that approximately 70% use condoms.54,55,57 In the WIHS, menopausal status itself was not found to impact condom use in HIV-positive women; however, overall condom use was reported in only 74% of premenopausal and 70% of postmenopausal women.54 When adjustments for sero-status were performed in a multivariable model, no significant difference in condom use was found between the HIV-positive and HIV-negative women.54

In addition to the aforementioned need for improved condom use in older adults, prevention strategies specific to HIV-positive individuals also include “treatment as prevention”. This strategy is garnering increased attention in light of the evidence showing that there is minimal risk of HIV transmission from people on cART with fully suppressed viral loads.58,59 Treatment as prevention can be an important HIV prevention strategy among older adults. However, clinicians should promote safer sex practices in all of their adult patients for the prevention of other STIs.

Studies have also attempted to determine if menopausal status affects cervical shedding of the HIV virus, thereby increasing the risk of sexual transmission. However, these results have been inconsistent. An in vitro study of ectocervical tissues from pre- (<45 years) and postmenopausal (>55 years of age) women, in which tissue samples were ex vivo infected with HIV-1 virus after hysterectomy, found higher levels of viral transcription in postmenopausal vs premenopausal samples.60 This could potentially have clinical implications if recently infected postmenopausal women, in the setting of already reduced condom use, are more likely to transmit the virus to others because of higher cervical viral shedding. However, this finding has not been replicated in any in vivo studies. Melo et al61 performed a cross-sectional study of pre- and postmenopausal, HIV-positive women in Brazil. They found no association between menopausal status and in vivo cervico-vaginal viral shedding; rather, degree of shedding was, as expected, associated with plasma viral load and vaginal pH.61 Once again, this emphasizes the importance of antiretroviral treatment and virologic suppression in the HIV prevention armamentarium.

Menopause and progression of HIV

As women with HIV transition through menopause, the progression of their infection and response to treatment in the setting of altered reproductive hormones is a key consideration. Older patients with HIV who are not on cART have lower baseline CD4 counts than younger patients.31 A component of this is likely related to age, as lymphocyte subsets, including CD4 counts, have been found to decrease with increasing age in non-HIV-infected adults.62 In those with HIV, timing of diagnosis is also a potential contributor. Older individuals are less likely to be tested for HIV and are more likely to be diagnosed with HIV later on in the course of the disease.11,31 This can result in lower CD4 set points at the time of antiretroviral initiation and a blunted response to treatment.11,28,31,63–65 However, menopausal status itself may also contribute to lower CD4 counts.28 With age and menopause, quantity of thymic tissue is reduced, which has implications for immunologic status.28 In a study of 382 HIV-positive women not on cART, with a known period of sero-conversion, a regression analysis modeling CD4 decline found a trend for postmenopausal women having lower CD4 counts 3 years after sero-conversion compared to premenopausal women (333 cells/μL vs 399 cells/μL, P=0.09).66 However, this result did not achieve statistical significance and furthermore, there was no difference in the rate of CD4 decline.66

More recent studies have generally yielded promising results, finding that menopausal status itself does not influence response to antiretroviral treatment.67,68 In 267 treatment-naïve women living with HIV, 47 of whom were postmenopausal, CD4 and viral load response to antiretroviral initiation did not differ between those who were pre- and postmenopausal.67 Postmenopausal women were able to maintain viral suppression through a 96-week follow-up period.67 Similarly, in a prospective cohort study of 383 antiretroviral-naïve, HIV-infected women in Brazil (85% premenopausal and 15% postmenopausal), menopausal status had no effect on treatment response at 24 months post-initiation of therapy.68 Pre- and postmenopausal women, with similar baseline CD4 counts (231 cells/mm3 compared to 208 cells/mm3, P=0.14), were equally likely to achieve virologic suppression. Interestingly, postmenopausal women had a lower median CD4 response than premenopausal women at the 24-month postantiretroviral therapy (ART) time point (184 cells/mm3 vs 273 cells/mm3, P=0.02); however, when this analysis was restricted to the women who achieved a viral load <400 copies/mL, there was no longer a difference in CD4 response (P=0.27).68

With increased age and menopause, alterations in drug pharmacokinetics may result from changes in volume of distribution and renal and hepatic clearance, which may further have implications for treatment responses and toxicities in elderly patients.69 Gervasoni et al attempted to determine if antiretroviral levels were affected by menopause. They found that between 28 pre- and 22 postmenopausal women, there was no difference in plasma levels of tenofovir (TDF), a commonly used nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI).70 Similarly, Cottrell et al found no difference in steady-state area under the curve plasma levels of the integrase inhibitor, raltegravir, between HIV-positive pre- vs postmenopausal women.71 Nevertheless, increased plasma drug concentrations are known to occur in elderly patients,72 and clearly need to be considered in the management of menopausal HIV-positive women as they could be at higher risk of drug toxicities than their younger, premenopausal counterparts.73 However, an independent effect of menopausal status on antiretroviral pharmacokinetics has not been established.

Impact of HIV infection on menopause

Age of menopause

Natural menopause typically occurs between the ages of 50 and 52 years.16,17 However, average age of menopause displays significant country-to-country variation and therefore, an examination of the age of onset of menopause in any subpopulation requires comparison to the national average.18,20 Most studies operationalize the term “early menopause” as menopause occurring between the ages of 40 and 45 years,13–15,19,22,74 and premature menopause (sometimes referred to as premature ovarian failure) as menopause occurring before the age of 40 years (Table 1).14,15,22 Early and premature menopause have important clinical implications. They are linked to alterations in mood and sexual function, declines in quality of life, development of comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and fragility fractures, and have been associated with earlier mortality.22,75–79 Therefore, an understanding of which populations are at increased risk of early and premature menopause is important for the counseling and management of female patients, as well as for the assessment of hormone therapy (HT) initiation if clinically indicated.9

Within the HIV-positive community, several reports have demonstrated that the average age of menopause is lower than the general population, and that women with HIV are at higher risk of developing early and premature menopause (Table 2).13,19,32,80–84 In a study of 268 women living with HIV in Thailand, the average age of menopause was 2.2 years earlier than the national average.82 In this study, the earlier age of menopause occurred independent of immunologic (CD4 count and viral load) and socio-demographic variables (age of menarche, marital status, parity, education, or income). Calvet et al19 assessed 667 HIV-positive women in Brazil, and found that median age of menopause was 48 years (interquartile range: 45–50 years), which is lower than the average age of menopause in the general population. Additionally, 27% of women in this study experienced menopause before 45 years of age.19 In the USA, age of menopause onset in women living with HIV has ranged from 46 to 50 years across various studies.13,80,81,83,84 Fantry et al demonstrated that in 120 HIV-positive women, 35% reported early menopause,13 while Schoenbaum et al found that 26% of HIV-positive women in New York experienced premature menopause, significantly higher than the 10% reported in the HIV-negative counterparts.81 Conversely, other studies have failed to demonstrate an earlier age of menopause when comparing HIV-positive and HIV-negative women.74,83,85 In a prospective cohort study of women living with HIV in France, the median age of onset of menopause was 49 years (interquartile range: 40–50 years), which was comparable to the general population in France.74,86 However, it is important to note that in this study, 22% of women reported early menopause and 12% experienced premature menopause.74 Cejtin et al performed a study of 1,335 women in the WIHS, and found no difference in the mean age of menopause between sero-positive (47.7 years) and sero-negative women (48 years).83,87 However, in a follow-up study of 1,431 women in the same cohort, the median age of menopause onset in the entire sample was 47 years, which is lower than the national average in the USA.85 This raises the possibility that the entire patient population was at risk of early menopause, thereby impairing the ability to demonstrate a difference between those with and without HIV infection. Alternatively, this study has been the only one to examine the age of menopause with a biochemical confirmation of ovarian failure, which may result in a more accurate assessment of menopause than self-report. Fantry et al also failed to show an earlier age of menopause in HIV-positive women in Baltimore.13 In this study, median age of menopause was 50 years (95% confidence interval 49–53); however, 55% of menopausal women reported early menopause (<45 years), and 35% reported premature ovarian failure (<40 years), which is substantially higher than the 5% and 1% of early menopause and premature ovarian failure reported in the general population, respectively.13,22 Unfortunately, this study did not enroll an HIV-negative control group for comparison, and the small sample size limits the interpretation of these proportions.

Table 2.

Summary of studies assessing age of menopause in women with HIV

| Authors | Study design | Location | Population | Menopause definition | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clark et al84 | Cross-sectional | USA | 52 HIV-positive women ≥40 years with adequate menopausal information; 50% postmenopausal | • FSH >35 mU/mL or | Mean age of menopause was 47 years (range 32–57 years) |

| • Self-report of amenorrhea >6 months with age ≥55 years or | |||||

| • Investigator’s diagnosis | |||||

| Schoenbaum et al81 | Cross-sectional | USA | 571 women 52.9% HIV-positive; 17.8% postmenopausal |

Self-report of amenorrhea >12 months | HIV independently associated with risk of menopause (OR 1.73) |

| Among those with HIV, having a CD4 count >500 (OR 0.191) or CD4 200–500 (OR 0.346) associated with decreased risk of menopause | |||||

| In HIV-positive women: | |||||

| • median age of menopause was 46 years (IQR 39–49 years) | |||||

| • 26% had early menopause | |||||

| In HIV-negative women: | |||||

| • median age of menopause was 47 years (IQR 44.5–48 years) | |||||

| • 10% had early menopause | |||||

| Boonyanurak et al82 | Cross-sectional | Thailand | 268 HIV-positive women ≥40 years of age; 20.5% women postmenopausal | Self-report of amenorrhea >12 months | Mean age of menopause was 47.3 years (SD 5.1 years); this was 2.2 years earlier than the mean age of menopause in general population in Thailand of 49.5 years (SD 3.1 years) |

| Calvet et al19 | Prospective cohortstudy Study followed premenopausal women enrolled between 1996 and 2010 |

Brazil | 667 HIV-positive women ≥30 years of age who were followed for a median of 5 years | Self-report of amenorrhea >12 months | Natural menopause occurred in 132/667 women during follow-up: |

| • median age of menopause was 48 years (IQR 45–50 years) | |||||

| • 27% had early menopause (<45 years) | |||||

| • 2.3% had premature menopause (<40 years) | |||||

| Early natural menopause associated with: | |||||

| • early menarche (HR 2.70) | |||||

| • smoking (HR 3.00) | |||||

| • HCV coinfection (HR 6.26) | |||||

| • CD4 count <50 (HR 6.64) | |||||

| Fantry et al13 | Cross-sectional | USA | 120 HIV-positive women ≥40 years of age; 25% postmenopausal | Self-report of amenorrhea >12 months | Median age of menopause was 50 years (95% CI 49–53 years) |

| • 20% had early menopause (40–45 years) | |||||

| • 35% had premature menopause (<40 years) | |||||

| Cejtin et al85 | Cross-sectional evaluation of data collected from the prospective Women’s Interagency Health Study (WIHS) | USA | 1,431 women ≤55 years of age • 1,139 HIV-positive • 292 HIV-negative |

Self-report of no menstrual period on 2 sequential visits with elevated FSH (>25 mIU/mL) | Median age of menopause was 47 years (range 35–55 years) (no difference between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women) |

| In HIV-positive women, no association of menopause with CD4 count, virologic suppression, AIDS-defining illness or ART | |||||

| Ferreira et al80 | Cross-sectional | Brazil | 96 HIV-positive and 155 HIV-negative women ≥40 years of age | Self-report of amenorrhea >12 months | Median age of menopause in HIV-positive women was 47.5 years |

| de Pommerol et al74 | Prospective cohort study | France | 404 HIV-positive women, followed for a median of 8.8 years; 24.3% postmenopausal | Self-report of amenorrhea >12 months | 24.3% were postmenopausal with median age of menopause of 49 years (IQR 40–50 years) |

| • 22% had early menopause (40–45 years) | |||||

| • 12% had premature menopause (<40 years) | |||||

| Earlier onset of menopause associated with: | |||||

| • African–American ethnicity (HR 8.16) | |||||

| • injection drug use (HR 2.46) | |||||

| No association with smoking, ART, nadir CD4, or AIDS-defining illness |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ART, antiretroviral therapy; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range.

The association between HIV-positivity and early menopause is likely multifactorial and subject to confounding by other factors, which contributes to variation in patient populations, and limits the ability to compare studies. It has been consistently shown that several risk factors for early menopause, including African–American ethnicity,74,81,85,88–90 smoking,19,81,84 and substance use,74,81 are more prevalent in HIV-positive patients and can affect the age of menopause.28 Additionally, the assessment of age of menopause is complicated by the subjective nature of the diagnosis. The WHO defines menopause based on a self-report of cessation of menstruation, but does not require an evaluation of any biochemical parameters, such as reproductive hormone levels.14,15 While this may be appropriate for the general population, it is potentially problematic in women living with HIV. In this population, the higher risk of menstrual irregularity, anovulation, and amenorrhea confounds the ability to accurately assess onset of menopause.18,85,91–93 Cejtin et al demonstrated this phenomenon in the aforementioned WIHS study. In this cohort, being HIV-positive was associated with a nearly twofold increased risk of having a period of amenorrhea lasting ≥12 months.85 Furthermore, of the 136 women with more than 1 year of amenorrhea, less than half (46.7%) had biochemical evidence of menopause with an elevated follicle-stimulating hormone, compared to 68.8% in the HIV-negative group. This indicated an independently higher risk for women with HIV to have amenorrhea in the absence of menopause, with an odds ratio of 3.16.85 Amenorrhea without menopause was more common in those with lower albumin, history of AIDS-defining illness, reduced income, and non-Hispanic ethnicity, highlighting a potential contribution of more severe illness and poorer nutritional status.85 Similarly, in a study of stored serum samples from HIV-positive women aged 20–42 years, 48% demonstrated evidence of anovulation, which was associated with lower CD4 counts.91 Therefore, in women with HIV, biochemical confirmation of menopause may be warranted, as this may have implications for contraception counselling, as well as screening for and management of menopause-associated comorbidities.85

The influence of immunologic status and virologic control on risk and age of menopause among women with HIV has been inconsistent. While some studies have demonstrated a correlation between lower CD4 count and higher risk of early menopause,19,74,81,83 other studies have failed to confirm this relationship.13,85

Symptoms of menopause

The exact role and impact of HIV infection on the experience of menopause is far from certain. Women living with HIV may report a different experience of and attitude toward menopause. Menopausal symptoms are contextually dependent, subject to influence by an array of biological, psychosocial and cultural factors, and are uniquely experienced by each individual woman.25–29,80,94 HIV-positive women may be more likely to experience menopausal symptoms than those without HIV infection; however, a consistent association has not been found. Furthermore, defining the relationship between HIV and menopausal symptoms is complicated by the difficulty in reliably distinguishing between symptomatology due to aging and menopause vs that due to HIV infection itself and the effects of ART.85,95,96

There has been some indication that women with HIV may be more likely to experience vasomotor symptoms when transitioning through menopause (Table 3).80,82,94,97 In their study of HIV-positive Thai women, Boonyanurak et al found that postmenopausal status was, not unexpectedly, associated with more vasomotor night sweats and change in sexual desire when compared to premenopausal women with HIV.82 However, all women in this study were HIV-positive. Therefore, the study findings indicate that women with HIV still experience the typical symptoms of menopause, but does not allow for a differentiation of symptom experience between those with and without infection. On the other hand, Ferreira et al did find that HIV infection was independently associated with a 65% higher risk of reporting menopausal symptoms.80 Similarly, in 66 women living in the USA, those with HIV reported a greater severity of hot flashes when compared to women without HIV.97 However, these findings have not been consistently reported in the literature, and there have been several studies that have not demonstrated a relationship between HIV-positivity and vasomotor symptoms.27,94,98–101 Lui-Filho et al found that vasomotor symptoms were associated with menopausal status, as expected, but were no different between sero-positive and sero-negative women in Brazil.27 Additionally, a comparison between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women living in New York City found no difference in the prevalence of hot flashes or vaginal dryness between the two groups.98 These contradictory findings also extend to the relationship between immunologic status and experience of symptoms. While one study has found that lower CD4 counts are associated with increased vasomotor symptoms,94 others have found no association80,82 or even the opposite in that symptoms were more prevalent in women with higher CD4 counts.84 Therefore, a clear association has not been established.

Table 3.

Summary of studies assessing menopausal symptoms in women with HIV

| Authors | Study design | Location | Population | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clark et al84 | Cross-sectional | USA | 52 HIV-positive women ≥40 years with adequate menopausal information; 50% postmenopausal | In HIV-positive menopausal women, higher CD4 count associated with increased prevalence of hot flashes: 23% in those with CD4 <200 vs 54% in those with CD4 >500 |

| Fantry et al13 | Cross-sectional | USA | 120 HIV-positive women ≥40 years of age; 25% postmenopausal | Postmenopausal HIV-positive woman had higher rates of: Hot flashes (86.7%) Vaginal dryness (53.3%) Menopausal status was associated with development of hot flashes (OR 4.2) |

| Miller et al94 | Cross-sectional | USA | 289 HIV-positive and 247 HIV-negative women | 96% of all women had at least 1 menopausal symptom 88.6% had psychological symptoms 61% had vasomotor symptoms HIV infection independently associated with increased symptoms (OR 1.24) |

| Ferreira et al80 | Cross-sectional | Brazil | 96 HIV-positive and 155 HIV-negative women ≥40 years of age | HIV infection independently associated with menopausal symptoms (OR 1.65) HIV-positive had high prevalence of psychological (97.9%) and vasomotor symptoms (78.1%) No association between menopausal symptoms and CD4 count |

| Boonyanurak et al82 | Cross-sectional | Thailand | 268 HIV-positive women ≥40 years of age; 20.5% women postmenopausal | In HIV-positive women, menopausal status was associated with: Night sweats (P=0.03) Change in sexual desire (P=0.01) versus general Thai population, HIV-positive more likely to have: Hot flashes (47% vs 37%) Night sweats (48% vs 21%) |

| Looby et al97 | Cross-sectional | USA | 33 HIV-positive women and 33 HIV-negative women between ages of 45–52 years |

HIV-positive women had greater severity of hot flashes compared to HIV-negative women (P=0.03) and greater severity of menopausal symptoms (P=0.008) HIV-positive women also had more: Sleep difficulties (P=0.04) Depression (P<0.05) Irritability (P<0.05) Anxiety (P<0.05) In HIV-positive women, severity of hot flashes did not correlate with CD4 count or duration of HIV infection |

| Johnson et al98 | Cross-sectional | USA | 150 HIV-positive women and 128 HIV-negative women |

No difference in prevalence of hot flashes or vaginal dryness based on HIV status HIV-positive women were less likely to know the etiology of their hot flashes or vaginal dryness |

| Lui-Filho et al27 | Cross-sectional | Brazil | 273 HIV-positive and 264 HIV-negative women aged 40–60 years of age | HIV sero-status not associated with menopausal symptoms (either vasomotor or psychological symptoms) Hot flashes and vaginal dryness more likely to occur in women who were perimenopausal or postmenopausal |

| Maki et al102 | Cross-sectional evaluation of data collected from the prospective Women’s Interagency Health Study (WIHS) | USA | 835 HIV-positive and 335 HIV-negative women aged 30–65 years | Prevalence of depressive symptoms did not differ between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women Depressive symptoms did vary with stage of menopause (33% in premenopausal, 47% in early perimenopausal, 42% in late perimenopausal, and 43% in postmenopausal) Early perimenopausal status had higher risk of depression (OR 1.92 in HIV-positive women) Among HIV-positive women: Increased depression if CD4 <200 (OR 2.14) Less depression when adherent to ART (OR 0.67) |

| Rubin et al99 | Cross-sectional | USA | 708 HIV-positive and 278 HIV-negative women aged 30–65 years | No difference in menopausal symptoms between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women (trend to HIV-positive having more sleep disturbances than HIV-negative [P=0.07]) Early perimenopausal women more likely to report depressive symptoms than premenopausal (OR 1.84); postmenopausal women more likely to report sleep disturbances than premenpausal (OR 1.83) HIV-positive women had worse outcomes on tests of cognitive function, but this was not associated with menopausal status; those with depression and/or anxiety also had poorer cognitive function |

| Sorlini et al107 | Cross-sectional | Italy | 20 HIV-positive and 21 HIV-negative women ≥65 years | No difference in depression between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women Among HIV-positive women, depression was associated with having a CD4 count <500 (P=0.02) A greater proportion of HIV-positive women than HIV-negative women had pathological scores on neuropsychological testing |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Mental health considerations in the postmenopausal period are also of particular importance. However, the relationship between mental health, HIV infection, and other socio-demographic confounders presents a multifaceted and complex picture. The menopausal transition itself, and the accompanying symptoms, regardless of HIV sero-status, can be associated with sleep disturbances, depression, and changes in cognition.94,102 Several studies have reported worsened mental health outcomes among women with HIV in the postmenopausal period, including panic attacks, depressive symptoms, and sleep disturbances.80,97,99,102–105 However, other studies have failed to replicate this finding.27,82,99,102,106,107 Depressive symptoms are also more likely to occur in women who are experiencing menopausal symptoms94,102,108–110 and have been associated with reduced quality of life,25,111 a negative attitude towards menopause,28,112 and decreased adherence to therapy.113,114

The impact of menopause and depressive symptoms on cognition is also an important consideration in HIV, as the virus is found in central nervous system tissue and is associated with the HIV-associated neurological disorders.115,116 Studies have suggested that compared to men, women with HIV are more likely to have lower education levels and increased difficulty accessing ART, which may result in their being more vulnerable to the development of HIV-associated neurological disorders and dementia.107,116,117 In a study of 41 women (20 HIV-positive and 21 HIV-negative) in Italy aged 65 years and older, women with HIV had worse performance on tests of executive function, processing speed, and verbal learning than age-matched, HIV-negative controls.107 Depression and anxiety can exacerbate these cognitive changes.99,115,116 In a study of 708 HIV-positive and 278 HIV-negative women living in the USA, women with HIV had a poorer performance on tests of verbal learning than those without HIV. While this study did not find an independent association between menopausal status and cognitive performance, verbal learning was negatively influenced by symptoms of anxiety, and was likely also influenced by poorer socioeconomic status.99 Therefore, if women with HIV are truly more likely to experience depression and anxiety, either independently or due to the menopausal transition and its myriad of symptoms and complications, cognitive function may also be affected.

These differential and contradictory findings with respect to HIV and menopausal symptoms may be related to differences in the study populations, which makes a direct comparison between study results difficult. Differences in socioeconomic status and ethnicity have been shown to influence symptoms and attitudes toward menopause and are likely contributing to the variation in findings.80,94,109,118 Women of African–American ethnicity have been found to report more symptoms of menopause when compared to Caucasian and Hispanic women.101 Additionally, lower education, poverty, and receipt of social assistance are associated with more menopausal symptoms and may be more prevalent in the HIV-positive community.27,80,94,109,118 Method of menopausal symptom assessment is also a key consideration. It has been found that women with HIV may be unable to distinguish between symptoms related to menopause vs those related to HIV itself and ART.95,98 They are also less likely than HIV-negative women to have knowledge of what to expect when going through the menopausal transition, which could potentially influence their expectations of aging and have a negative impact on mood if they do not understand why certain symptoms are occurring.95,98 These findings may be related to the earlier age of menopause in HIV-infection, in which case symptoms might be misattributed to HIV itself because menopause would be unexpected.98 Lower education and socioeconomic status in certain study populations may also partially explain these misperceptions.95 Therefore, it is important for clinicians to discuss aging and menopause with their HIV-positive patients, so that they can be better prepared for any changes or symptoms they might develop.

Hormone therapy has been shown to have beneficial effects in certain women with menopause, particularly with respect to vasomotor symptoms and bone health.84,119 However, practitioners may be reluctant to provide HT to women with HIV for fear of worsening HIV status, or due to concerns regarding toxicity, increased pill burden, and/or drug–drug interactions with ART.84 Consequently, rates of HT use in HIV-positive women are typically very low at approximately 10% or less.13,32,84,120 There have been no published studies examining the utility and/or safety of HT in women with HIV, and there is limited data on use of HT in women on cART. Though there may be drug–drug interactions between HT and some protease inhibitors (PIs) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), including fosamprenavir (PI) and efavirenz (NNRTI), newer antiretroviral agents likely do not possess the same pharmacologic concerns.9 Prolonged HT has been associated with other medical complications such as breast cancer, thromboembolic disease, and cardiovascular disease. Therefore, current HIV primary care guidelines are similar to those for the general population and suggest that HT, if used, should be provided at the lowest effective dose and for a limited time only.121 However, HT is likely being underutilized in women with HIV and should be considered for those who might otherwise benefit due to severe menopausal symptoms, as long as there are no contraindications to therapy.32

Bone mineral density (BMD)

The higher prevalence of amenorrhea and earlier age of menopause that accompany HIV infection in women predisposes them to earlier and more severe bone loss when compared to those without HIV. Osteoporosis, a disorder characterized by decreases in bone density and quality and increased susceptibility to fracture, represents a significant global health burden, particularly for postmenopausal women.120,122 The WHO operationally defines osteoporosis as having a BMD score of 2.5 or more standard deviations below the mean for young, healthy women (ie, a T-score ≤2.5).122–124 Osteoporosis affects more than 75 million people in developed countries; globally, it is responsible for more than 8.9 million fractures per year,124 and leads to reductions in quality of life, and a higher risk of morbidity and mortality.120,125,126 While increased age and postmenopausal status are the two most important factors predisposing to low BMD and osteoporosis, a variety of additional factors, including lifestyle behaviors, chronic medical conditions and medications, also contribute to bone loss.122,127,128 HIV is an important risk factor for impaired bone health.120,122,129–134 The prevalence of low BMD among those with HIV ranges from 30% to 70%,131,134 while up to 15% of patients with HIV have osteoporosis.135–137 However, the development of bone disease in HIV is likely a multifactorial process that includes the effects of HIV infection itself, higher prevalence of other osteoporosis risk factors, as well as the impact of ART.9,23,120,122,132–134,138–142

Several studies have demonstrated that patients with HIV are more likely to experience additional osteoporosis risk factors including cigarette smoking and alcohol use, African–American or Hispanic ethnicity, decreased body mass index, vitamin D deficiency, chronic steroid use, amenorrhea, and hypogonadism.9,23,122,127,128,131,134,143–154 However, there is evidence that HIV infection itself, independent of its association with these other factors, contributes to bone loss (Table 4).120,122,129,132,133,141,142,144,147,148,155,156 A meta-analysis has shown that HIV is associated with a 6.4-fold increased risk of osteopenia/low BMD and a threefold increased risk of osteoporosis.129 In a cross-sectional study of 120 women over the age of 40 years, those with HIV who were postmenopausal had a lower mental index and antegonial depth on panoramic jaw X-ray examination when compared to those without HIV, while premenopausal HIV-positive women only had lower antegonial depth than HIV-negative women.156 Yin et al have performed several studies demonstrating lower BMD in women with HIV (Table 4). In a cross-sectional study of HIV-positive, postmenopausal women, mean BMD in the lumbar spine and total hip were significantly lower when compared to historical matched controls.144 Additionally, those with HIV were more likely to have documented osteoporosis based on T-scores at the lumbar spine (43% vs 23%) and hip (10% vs 1%) when compared to the HIV-negative controls.144 In a longitudinal cohort of women in New York, adjusted analyses demonstrated that HIV-positivity was associated with lower BMD at the lumbar spine and total hip, and that women with HIV were also more likely to have higher levels of markers of bone turnover.132 However, this did not translate to a higher risk of fragility fracture in this population.132 In a subsequent study of HIV-positive and HIV-negative women, HIV status was not associated with an increased risk of fracture, nor was CD4 count or use of ART.149 While some studies have corroborated Yin et al’s findings132,149 that fracture incidence does not increase with HIV,142 other studies have found evidence to the contrary.146,157–162 In a Canadian study of 137 HIV-positive patients and 402 HIV-negative controls, those with HIV had a 1.7-fold higher lifetime risk of fragility fracture.146 Similarly, association between bone loss and CD4 count among women with HIV has also been inconsistent.120,122,129,132,135,144,145,147,163–165

Table 4.

Summary of studies assessing bone mineral density (BMD) and osteoporosis in women with HIV and menopause

| Authors | Study design | Location | Population | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yin et al144 | Cross-sectional | USA | 31 HIV-positive postmenopausal women compared to 186 historical-matched (age, ethnicity) HIV-negative controls | Mean BMD lower in HIV-positive group vs controls |

| Prevalence of osteoporosis 42% (vs 23%) at lumbar spine (P=0.003) | ||||

| Prevalence of osteoporosis 10% (vs 1%) at total hip (P=0.003) | ||||

| Correlates of low BMD were: | ||||

| Years since menopause (P=0.02) | ||||

| Lowest weight (P=0.001) | ||||

| No association with duration of HIV infection, ART, CD4 count | ||||

| Arnsten et al133 | Cross-sectional | USA | 263 HIV-positive and 232 HIV-negative women ≥40 years of age | HIV-positive women had lower BMD at femoral neck (P=0.001) and lumbar spine (P=0.04) vs HIV-negative women |

| HIV was an independent predictor of low BMD (especially in non-Black women) | ||||

| CD4 count, ART and use of PIs not associated with low BMD | ||||

| Anastos et al155 | Cross-sectional | USA | 274 HIV-positive and 152 HIV-negative women | Prevalence of low BMD was higher in ART-naïve HIV-positive women compared to HIV-negative women (OR 4.36), indicating an independent association with HIV infection |

| Prevalence of low BMD higher in women receiving PI-therapy (OR 3.72) compared to HIV-negative women | ||||

| PI-based ART associated with lower BMD than non-PI-ART (P=0.014) | ||||

| Longer lopinavir use correlated with lower BMD (P=0.006) and longer efavirenz use associated with higher BMD (P=0.004) | ||||

| Yin et al132 | Cross-sectional analysis of data from a prospective cohort study | USA | 92 HIV-positive and 95 HIV-negative women ≥40 years of age who were postmenopausal and not on hormone therapy | HIV-positive women were more likely to have low BMD at lumbar spine, femoral neck and total hip |

| BMD was 5.9% lower in HIV-positive vs HIV-negative women at the total hip | ||||

| HIV was an independent predictor of BMD at the lumbar spine and total hip | ||||

| No difference between HIV-positive and HIV-negative for fragility fractures | ||||

| No difference by ART status | ||||

| Yin et al140 | Cross-sectional analysis of data from a prospective cohort study | USA | 92 HIV-positive and 95 HIV-negative women ≥40 years of age who were postmenopausal and not on hormone therapy | HIV-positive women had increased bone turnover markers compared to HIV-negative women |

| No difference between: | ||||

| ART vs no ART | ||||

| Ritonavir vs no ritonavir in ART regimen | ||||

| Greater induction of peripheral blood mononuclear cells into osteoclast-like cells when exposed to autologous HIV-positive serum (vs HIV-negative) and serum containing ritonavir (vs non-ritonavir-based ART) | ||||

| Pinto Neto et al141 | Cross-sectional | Brazil | 300 HIV-positive patients with median age 46 years (57.7% male and 42.3% female) | Low BMD in 54.7% of patients (95% CI 49.1%–60.3%) |

| Independent predictors of low BMD were: | ||||

| BMI <25 kg/m2 (OR 2.9) | ||||

| Menopause (OR 13.4) | ||||

| Undetectable viral load (OR 7.9) | ||||

| Zidovudine use (OR 0.2) and nevirapine use (OR 0.1) were protective against low BMD | ||||

| Sharma et al145 | Longitudinal | USA | 245 HIV-positive and 219 HIV-negative women | HIV-positive women had lower baseline BMD at femoral neck (P=0.02) and total hip (P<0.01) than HIV-negative women, but there was no difference in prevalence of osteoporosis between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women |

| No difference between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in rate of BMD decline over time | ||||

| Also no difference in BMD decline between: | ||||

| Tenofovir vs no tenofovir use | ||||

| PI vs no-PI use | ||||

| In multivariate analysis, menopause and chronic HCV infection associated with greater decline in BMD | ||||

| Gomes et al120 | Cross-sectional | Brazil | 273 HIV-positive women aged 40–60 years; 206/273 answered questions related to study | 33.5% had low BMD at lumbar spine and 33.1% at femoral neck |

| Low BMD at lumbar spine and femoral neck associated with: | ||||

| Age >50 years (P<0.01 at LS and FN) | ||||

| Menopause (P<0.01 at LS and FN) | ||||

| Increased FSH >40 mIU/mL (P<0.001 at LS and P<0.01 at FN) | ||||

| Menopause associated with 23-fold increased risk of low BMD at lumbar spine (P<0.01) and 57-fold increased risk of low BMD at femoral neck (P<0.01) | ||||

| No association between low BMD and smoking, alcohol, nadir CD4 count, viral load, tenofovir use, protease inhibitors, or duration of HIV infection | ||||

| Dravid et al147 | Cross-sectional | India | 536 HIV-positive patients (66% men and 34% women) with median age 42 years | In ART-naïve patients: |

| 67% had low BMD and 29.6% had osteoporosis | ||||

| In ART-experienced patients: | ||||

| 80.4% had low BMD and 36.6% had osteoporosis | ||||

| Low BMD associated with: | ||||

| Increased age (P<0.001) | ||||

| Reduced BMI (P<0.001) | ||||

| Smoking (P=0.05) | ||||

| Menopause (P=0.03) | ||||

| Prior et al146 | Case-control | Canada | 138 HIV-positive women and 402 HIV-negative controls matched for age and geographic region | HIV-positive women more likely to have other osteoporosis risk factors such as smoking, menstrual irregularity, weight loss, glucocorticoid use |

| No difference in BMD between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women | ||||

| HIV-positive cases had higher rates of lifetime fragility fractures compared to HIV-negative controls (26.1% vs 17.7%, OR 1.7); however, HIV status itself not associated with fracture in multivariable analysis when other osteoporosis risk factors taken into account | ||||

| Yin et al149 | Prospective cohort study – Women’s Interagency Health Study (WIHS) | USA | 1,728 HIV-positive and 663 HIV-negative women followed for median 5.4 years | One-third of new fractures were fragility fractures |

| No difference between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in history of self-reported fracture | ||||

| In multivariate analysis, new fracture was associated with older age, white race, HCV infection, and increased creatinine, but not HIV status | ||||

| In HIV-positive patients, older age, white race, smoking, and history of ADI were associated with new fracture, while NNRTIs were slightly protective (OR 0.92); there was no association with ART, CD4 count or cumulative tenofovir exposure |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; BMI, body mass index; PI, protease inhibitor; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IDU, injection drug use; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; OR, odds ratio; BMD, bone mineral density; CI, confidence interval; LS, lumbar spine; FN, femoral neck; ADI, AIDS-defining illness; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

Antiretroviral therapy has been associated with a decline in BMD within the first 1–2 years of therapy.122,129,134,138,139,166–168 However, the relationship between long-term ART and bone health is not as clear, and bone loss may stabilize with ongoing therapy.120,128,138,147 In vitro studies have shown several antiretrovirals cause changes in bone metabolism; zidovudine (AZT), an NRTI,169 and ritonavir, a PI,140 are associated with increased osteoclast activity, while TDF causes renal phosphate wasting and predisposes to osteoporosis.137,167,168,170,171 However, while TDF use has consistently been shown to cause bone loss,137,141,167,168,171 clinical studies examining other antiretrovirals have not necessarily confirmed the in vitro findings.141,147,167,172 For example, in a study of 300 HIV-positive women, ART use overall was not associated with a decrease in BMD, and AZT was found to be protective against bone loss.141 Another study found that NRTI use was associated with BMD decline.173 Similarly, the relationship between PIs and BMD is inconsist ent,120,128,134,145,155,167,174–177 while NNRTIs and integrase inhibitors, particularly raltegravir, appear to have less of an impact on bone health.122,137,149,178,179

Given that HIV is associated with changes in BMD, some experts suggest that HIV should be included in the list of medical conditions that cause secondary osteoporosis.131 However, regional osteoporosis guidelines vary in their recommendations regarding screening (Table 5).121,131,180,181 Most guidelines suggest that osteoporosis risk be estimated based on a comprehensive clinical tool (such as the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool [FRAX])182 to calculate a 10-year fracture risk (Table 6).123,131,183 HIV is not included in this clinical tool. In 2015, specific guidelines were published for management of bone disease in individuals with HIV (Tables 5 and 7).131 These guidelines suggest that all HIV-positive individuals should be assessed for their fracture risk, based on the clinical tool suggested in their appropriate regional guideline. HIV-positive individuals with one major risk factor for osteoporosis (such as men ≥50 years and postmenopausal women) should undergo screening with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Table 6).131,134 If no major risk factor exists, patients should be assessed according to age-specific recommendations: for men and premenopausal women ≥40 years of age, fracture riskshould be calculated and those at intermediate-to-high risk should undergo dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry screening.131

Table 5.

Guidelines for assessment of BMD in patients with HIV

| Source and location | Year of publication | Recommendations for screening |

|---|---|---|

| Brown et al. Recommendations for evaluation and management of bone disease in HIV. Clin Infect Dis.131 [USA]a | 2015 | It is appropriate to assess all HIV-positive patients for risk of low BMD and fragility fracture |

| All patients >50 years of age should have height assessment every 1–2 years | ||

| BMD assessment with DEXA-scan is recommended for: | ||

| All patients who have a major risk factor for osteoporosis | ||

| Postmenopausal women | ||

| Men ≥50 years of age | ||

| Previous fragility fracture | ||

| Glucocorticoid use at dose ≥ equivalent of prednisone 5 mg/day for >3 months | ||

| High falls risk | ||

| All other patients should be assessed for osteoporosis risk based on age-specific recommendations: | ||

| Assessment with comprehensive clinical tool (such as the FRAXb) is suggested for: | ||

| Premenopausal women >40 years of age | ||

| Men 40–49 years of age | ||

| Some experts suggest those with HIV should be considered to have a secondary cause of osteoporosis when utilizing the FRAX tool | ||

| Those who have an intermediate to high risk of fracture on FRAX should go on to have DEXA scan | ||

| No screening required for those <40 years of age unless other risk factors (as mentioned earlier) are present | ||

| Aberg et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with HIV: 2013 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis.121 [USA] | 2013 | Baseline bone densitometry (DEXA) screening is recommended for: |

| Postmenopausal women | ||

| Men ≥50 years of age | ||

| Asboe et al. British HIV Association guidelines for the routine investigation and monitoring of adult HIV-1-infected individuals, 2011. HIV Med.180 [UK] | 2011 | Assess patients for risk factors for reduced BMD (eg, with FRAX) at: |

| Initial HIV diagnosis | ||

| Prior to initiation of ART | ||

| Reassess these risk factors every 3 years when on ART and for those ≥50 years of age | ||

| BMD assessment (usually with DEXA) should be performed for: | ||

| Men ≥70 years of age | ||

| Women ≥65 years of age | ||

| Consider DEXA in men and women ≥50 years of age if intermediate to high risk FRAX or other risk factorsc | ||

| European AIDS Clinical Society. EACS Guidelines Version 7.1. EACS; 2014.181 [Europe] | 2014 | Consider all patients for classic risk factorsd for osteoporosis |

| Measure 25(OH) vitamin D in all persons at presentation | ||

| Consider DEXA for patients with ≥1 of the following (preferably before ART initiation): | ||

| Postmenopausal women | ||

| Men ≥50 years of age | ||

| History of low-impact fracture | ||

| High falls riske | ||

| Clinical hypogonadism | ||

| Oral glucocorticoid use at dose ≥ equivalent of prednisone 5 mg/day for >3 months | ||

| Assess effect of risk factors by including DEXA results into FRAX | ||

| Do not use for those <40 years of age | ||

| Consider using HIV as a cause of secondary osteoporosis |

Notes:

Reproduced from Brown TT, Hoy J, Borderi M, et al. Recommendations for evaluation and management of bone disease in HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(8):1242–1251,131 by permission of Oxford University Press. Copyright ©2015.

FRAX: World Health Organization Fracture Risk Assessment Tool: https://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp; Use country-specific FRAX algorithm; consider checking off box for “secondary osteoporosis” in patients with HIV (expert opinion).131

Additional risk factors include HIV or related risk factors, such as increased duration of HIV infection, low nadir CD4 count and hepatitis virus co-infection.

Classic risk factors include older age, female sex, hypogonadism, family history of hip fracture, low BMI (<19 kg/m2), vitamin D deficiency, smoking, physical inactivity, history of low-impact fracture, alcohol excess, steroid exposure (equivalent to ≥5 mg prednisone per day for >3 months).

Using Falls Risk Assessment Tool: www.health.vic.gov.au/agedcare/maintaining/falls/downloads/ph_frat.pdf.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; DEXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; FRAX, Fracture Risk Assessment Tool; BMD, bone mineral density; BMI, body mass index.

Table 6.

Interpretation of fracture risk assessment and DEXA scores in assessment of bone disease

| Source | Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Risk of Fracturea | ≤10% risk of major osteoporotic fracture in 10 years | Low risk |

| 10%–20% risk of major osteoporotic fracture in 10 years | Moderate risk | |

| ≥20% risk of major osteoporotic fracture in 10 years and/or ≥3% risk of hip fracture | High risk | |

| DEXA scanb | T-score. −1.0 | Within normal limits |

| T-score ≤−1.0 but. −2.5 | Osteopenia | |

| T-score ≤−2.5 | Osteoporosis |

Notes:

Based on a validated clinical tool such as the FRAX182 or the Canadian Association of Radiologists and Osteoporosis Canada (CAROC) tool.123

Use T-scores for postmenopausal women and men aged ≥50 years; use z scores for patients aged <50 years; based on the femoral neck score.124 Reproduced from Brown TT, Hoy J, Borderi M, et al. Recommendations for evaluation and management of bone disease in HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(8):1242–1251,131 by permission of Oxford University Press. Copyright ©2015.

Abbreviations: FRAX, Fracture Risk Assessment Tool; DEXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Table 7.

2015 Guidelines for management of bone disease in patients with HIV

| Source | Year of publication | Patient population | Recommendation for repeat screening | Recommendations for management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al. Recommendations for evaluation and management of bone disease in HIV. Clin Infect Dis.131 | 2015 | Patients younger than 40 years | No routine screening suggested; assess when develop major risk factor or become >40 years of age | All patients: Adequate calcium intake Adequate vitamin levels and supplementation if requiredb Lifestyle modifications Smoking and alcohol cessation Falls prevention Exercise |

| Patients aged 40–50 years with a low 10-year fracture risk based on FRAX (no DEXA required) | Monitor FRAX every 2–3 years | |||

| Patients with moderate 10-year fracture risk: FRAX ≥10% but <20% Lowest T-score >−2.5 No history of hip or vertebral fracture |

Repeat DEXA in 1–2 years if advanced osteopenia (T-score between −2.00 and −2.49) Repeat DEXA in 5 years if mild osteopenia (T-score between −1.00 and −1.99) |

|||

| Patients with clinical osteoporosis: Patients with high 10-year fracture riska T-score <2.5 at FN, TH or LS on DEXA scan Previous hip or vertebral fracture |

Repeat DEXA in 2 years | Exclude secondary causes of osteoporosisc Treat osteoporosis as per general population: Bisphosphonates first-line therapy (alendronate or zoledronic acid preferred) Review therapy at 3–5 years Consider avoiding TDF or boosted PIs if low BMD or osteoporosis (but benefits of ART outweigh risks) |

Notes:

≥20% risk of major osteoporotic fracture in 10 years and/or ≥3% risk of hip fracture (with or without incorporation of BMD result); based on validated clinical tool such as the FRAX.

Check vitamin D levels in those with low BMD or previous fracture or risk factors for vitamin D deficiency (dark skin, sun avoidance, malabsorption, obesity, chronic kidney disease, or on treatment with efavirenz); supplemental vitamin D if deficient and target level >30 μg/L.

Secondary causes of osteoporosis include: type 1 diabetes mellitus, osteogenesis imperfecta in adults, untreated long-standing hyperthyroidism, hypogonadism, or premature menopause (<45 years), chronic malnutrition, malabsorption, and chronic liver disease. Reproduced from Brown TT, Hoy J, Borderi M, et al. Recommendations for evaluation and management of bone disease in HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(8):1242–1251,131 by permission of Oxford University Press. Copyright ©2015.

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; ART, antiretroviral therapy; PIs, protease inhibitors; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Viread®); FN, femoral neck; TH, total hip; LS, lumbar spine; FRAX, Fracture Risk Assessment Tool; DEXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

With respect to management, those with HIV should be managed as per the general population, including both lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic therapy where appropriate (Table 7). Secondary causes of bone loss should be excluded. Many patients with HIV will have risk factors for vitamin D deficiency, and should be assessed for supplementation if insufficiency or deficiency exists.122,131,184 Bisphosphonates do not have significant interactions with ART and are considered safe for use in those with HIV.122 Alendronate and zoledronic acid are the preferred agents in HIV as they have been evaluated and found to be effective in this population.122,131,185–190 If bisphosphonates cannot be used, teriparatide is the suggested second-line agent, though it has not been specifically studied in patients with HIV.122,134 For the most part, the benefits of ART with respect to virologic control are considered to outweigh the risks of potentially exacerbating bone loss. However, in those patients who are at high risk of fracture based on a comprehensive clinical assessment, clinicians may consider avoiding TDF or PIs if reasonable alternatives are available.131,134

Future directions

While the body of evidence continues to grow, further research regarding the complex interaction between HIV and menopause is needed. Larger studies are required to determine if menopause affects antiretroviral pharmacokinetics and response to therapy. The influence of menopause on cervico-vaginal shedding of the HIV virus may have implications for risk of transmission and should be further evaluated. It will also be important to determine if earlier self-report of menopause is truly due to an earlier age of onset in women with HIV, or is confounded by a higher risk of amenorrhea without menopause. Therefore, future studies should consider including biochemical confirmation of menopause in order to better define this relationship. There are currently no studies specifically examining the efficacy and safety of HT in women with HIV, which likely contributes to underuse in this population. Finally, ongoing monitoring of bone health in the context of newer antiretrovirals, particularly with the introduction of tenofovir alafenamide fumarate, will be important to ensure that women are on safe and optimal anti-retroviral regimens as they transition through menopause.

Conclusion

Menopause is a pivotal life event for women, but each individual woman will have her own unique experience of the process. HIV infection is potentially associated with an increased risk of earlier menopause, more prevalent and pronounced menopausal symptoms, and likely exacerbates the changes in bone health that accompany the menopausal transition. Increasing age and menopause do not result in a cessation of sexual activity, but can affect the degree to which individuals perceive themselves to be at risk of transmitting and acquiring HIV infection, and can influence their engagement in safe sexual practices. Therefore, as patients with HIV live longer in the era of effective cART, the management of HIV infection will continue to increase in complexity. This management must occur in conjunction with the screening and management guidelines for age-related comorbidities, and must include an evaluation of the potential interactions between HIV, sexual behaviors, and other pivotal life events, including menopause.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose in this work.

References

- 1.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration Life expectance of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):293–299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison KM, Song R, Zhang X. Life expectancy after HIV diagnosis based on national HIV surveillance data from 25 states, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(1):124–130. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b563e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lima VD, Hogg RS, Harrigan PR, et al. Continued improvement in survival among HIV-infected individuals with newer forms of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2007;21(6):685–692. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32802ef30c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, et al. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2013. [Accessed November 16, 2015]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [homepage on the Internet] HIV Among Women. Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Tuberculosis Prevention: US Department of Health and Human Services; [Accessed November 16, 2015]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html#refa. Updated June 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health Agency of Canada . HIV and AIDS in Canada: Surveillance Report to December 31, 2013. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; Public Health Agency of Canada; 2014. 2014. [Accessed November 16, 2015]. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/aids-sida/publication/survreport/2013/dec/assets/pdf/hiv-aids-surveillence-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cejtin HE. Care of the Human immunodeficiency virus-infected menopausal woman. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(2):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanapathipillai R, Hickey M, Giles M. Human immunodeficiency virus and menopause. Menopause. 2013;20(9):983–990. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e318282aa57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [homepage on the Internet] HIV Among People Aged 50 and Over. Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Tuberculosis Prevention: US Department of Health and Human Services; [Accessed November 16, 2015]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html. Updated May 12, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychological Association [homepage on the Internet] Karpiak S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in older adults living with HIV/AIDS. American Psychological Association; 2014. [Accessed November 16, 2015]. Available from: http://www.apa.org/pi/aids/resources/exchange/2014/01/anti-retroviral-therapy.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fantry LE, Zhan M, Taylor GH, Sill AM, Flaws JA. Age of menopause and menopausal symptoms in HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19(11):703–711. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . WHO Scientific Group on Research on the Menopause in the 1990’s. Geneva, Switzerland; 1996. [Accessed November 16, 2015]. (WHO Technical Report Series 866). Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/41841/1/WHO_TRS_866.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Menopause Society [homepage on the Internet] Menopause Terminology. International Menopause Society; [Accessed November 16, 2015]. Available from: http://www.imsociety.org/menopause_terminology.php. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brambilla DJ, McKinlay SM. A prospective study of factors affecting age at menopause. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42(11):1031–1039. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKinlay SM, Bifano NL, McKinlay JB. Smoking and age at menopause in women. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103(3):350–356. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-3-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conde DM, Pinto-Neto AM, Costa-Paiva L. Age at menopause of HIV-infected women: a review. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24(2):84–86. doi: 10.1080/09513590701806870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calvet GA, Grinsztejn BG, Quintana MS, et al. Predictors of early menopause in HIV-infected women: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):765.e1–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas F, Renaud F, Benefice E, de Meeus T, Guegan JF. International variability of ages at menarche and menopause: patterns and main determinants. Hum Biol. 2001;73(2):271–290. doi: 10.1353/hub.2001.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop +10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Menopause. 2012;19(4):387–395. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824d8f40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shuster LT, Rhodes DJ, Gostout BS, Grossardt BR, Rocca WA. Premature menopause or early menopause: long-term health consequences. Maturitas. 2010;65(2):161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan MD, Maslow BS, Santoro N, Schoenbaum E. HIV and menopause. Menopause Int. 2008;14(4):163–168. doi: 10.1258/mi.2008.008027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumel JE, Castelo-Branco C, Binfa L, et al. Quality of life after the menopause: a population study. Maturitas. 2000;34(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conde DM, Pinto-Neto AM, Santos-Sa D, Costa-Paiva L, Martinez EZ. Factors associated with quality of life in a cohort of postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22(8):441–446. doi: 10.1080/09513590600890306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Utian WH. Psychosocial and socioeconomic burden of vasomotor symptoms in menopause: a comprehensive review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:47. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lui-Filho JF, Valadares ALR, Gomes DC, Amaral E, Pinto-Neto AM, Costa-Paiva L. Menopausal symptoms and associated factors in HIV-positive women. Maturitas. 2013;76(2):172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kojic EM, Wang CC, Cu-Uvin S. HIV and menopause: a review. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16(10):1402–1411. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zapantis G, Santoro N. The menopausal transition: characteristics and management. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17(1):33–52. doi: 10.1016/s1521-690x(02)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zablotsky D, Kennedy M. Risk factors and HIV transmission to midlife and older women: knowledge, options, and the initiation of safer sexual practices. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(Suppl 2):S122–S130. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Althoff KN, Gebo KA, Gange SJ, et al. CD4 count at presentation for HIV care in the United States and Canada: are those over 50 years more likely to have a delayed presentation? AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:45. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samuel MI, Welch J, Tenant-Flowers M, Poulton M, Campbell L, Taylor C. Care of HIV-positive women aged 50 and over – can we do better? Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(4):303–305. doi: 10.1177/0956462413504553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duffus WA, Kettinger L, Stephens T, et al. Missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis of HIV infection – South Carolina, 1997–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(47):1269–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duffus WA, Weis K, Kettinger L, Stephens T, Albrecht H, Gibson JJ. Risk-based HIV testing in South Carolina health care settings failed to identify the majority of infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(5):339–345. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization . WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children. WHO; 2007. [Accessed November 16, 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/HIVstaging150307.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor TN, Weedon J, Golub ET, et al. Longitudinal trends in sexual behaviors with advancing age and menopause among women with and without HIV-1 infection. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(5):931–940. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0901-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waite LJ, Laumann EO, Das A, Schumm LP. Sexuality: measures of partnerships, practices, attitudes, and problems in the national social life, health and aging study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(Suppl 1):i56–i66. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, et al. The social organization of sexuality: sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunn ME, Cutler N. Sexual issues in older adults. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14(2):6–69. doi: 10.1089/108729100317984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]