Abstract

Background

The literature distinguishes two types of social normative influences on adolescent alcohol use, descriptive norms (perceived peer alcohol use) and injunctive norms (perceived approval of drinking). Although theoretical formulations suggest variability in the salience and influence of descriptive and injunctive norms, little is understood regarding for whom and when social norms influence adolescent drinking. Strong agentic and communal social goals were hypothesized to moderate the influence of descriptive and injunctive norms on early adolescent alcohol use, respectively. Developmental changes were also expected, such that these moderating effects were expected to get stronger at later grades.

Methods

This longitudinal study included 387 adolescents and 4 annual assessments (spanning 6th to 10th grade). Participants completed questionnaire measures of social goals, social norms, and alcohol use at each wave.

Results

Multilevel logistic regressions were used to test prospective associations. As hypothesized, descriptive norms predicted increases in the probability of alcohol use for adolescents with strong agentic goals, but only in later grades. Injunctive norms were associated with increases in the probability of drinking for adolescents with low communal goals at earlier grades, whereas injunctive norms were associated with an increased probability of drinking for adolescents with either low or high communal goals at later grades. Although not hypothesized, descriptive norms predicted increases in the probability of drinking for adolescents high in communal goals in earlier grades whereas descriptive norms predicted drinking for adolescents characterized by low communal goals in later grades.

Conclusions

The current study highlights the importance of social goals when considering social normative influences on alcohol use in early and middle adolescence. These findings have implications for whom and when normative feedback interventions might be most effective during this developmental period.

Keywords: social norms, social goals, adolescent alcohol use

Introduction

Adolescence is the developmental period most strongly associated with the initiation and escalation of substance use (Colder et al., 2002). Adolescent alcohol use is of concern because it is often associated with a variety of negative consequences including increased alcohol use later in life (Hawkins et al., 1997), decreased academic performance (Balsa et al., 2011), and illicit drug use (Hill et al., 2000). Understanding the factors that influence adolescent drinking is important for developing empirically supported etiological models and effective interventions.

During adolescence, an increasing amount of time is spent outside of the home and in the context of peers (Spear, 2000), and peers are believed to play a central role in the initiation and escalation of adolescent alcohol use (Barnes et al., 2007). Adolescents are often motivated to align their behaviors and opinions with those of their peers in part because they have a strong desire to maintain close peer relationships and to be accepted by their peers groups (Collins and Steinberg, 2006). Thus, perceived peer norms (e.g., perceptions of the behaviors peers engage in as well as perceptions of behaviors peers approve of) are viewed as an important mechanism through which peers influence a variety of behaviors, including alcohol use (Borsari and Carey, 2001; Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004). In this study, we propose that the influence of perceived norms on adolescent early alcohol use is not uniform and test whether the strength of the association between perceived norms and alcohol use depends on the type of social norm (descriptive or injunctive), an adolescent's social goals, and grade.

Social Norms

According to the Focus Theory of Normative Conduct, individuals adjust their behavior to match that of a relevant referent group because norms dictate what behaviors are socially acceptable (Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004). In this regard, social norms have been conceptualized as informal rules and standards that groups adopt to guide and constrain behavior (Cialdini and Trost, 1998). The evidence suggests that two types of perceived social norms are particularly relevant for understanding adolescent drinking behaviors, descriptive norms (perceptions of peer drinking) and injunctive norms (perceptions of the acceptability of peer drinking) (Borsari and Carey, 2001). Descriptive and injunctive norms have been associated with a variety of drinking behaviors in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Collins and Spelman, 2013 Larimer et al., 2004; Read et al., 2002; Teunissen et al., 2012; Authors, 2010; Voogt et al., 2013).

An important feature of the Focus Theory of Normative Conduct is that social norms are posited to influence behavior when they are salient (Cialdini et al., 1990). Understanding the conditions under which descriptive versus injunctive norms are made more salient is of critical importance because it has important implications for intervention and theory. For example, if individual characteristics differentially impact the salience of different norms, then such knowledge could be used to target either descriptive or injunctive norms as part of an individually tailored intervention strategy to enhance the impact of existing norms interventions (Neighbors et al., 2008; Walters and Neighbors, 2005). We propose that individual differences in social goals will impact the degree to which an adolescent will conform to descriptive and injunctive alcohol use norms. That is, social goals operate as moderators of the association between social norms and adolescent alcohol use, but these moderating effects will depend on the type of social norm as well as the specific nature of social goals.

Social Goals

Social goals refer to the value placed on appearing a certain way in social interactions and they are organized around a circumplex structure with two orthogonal axes that includes a vertical axis representing agentic goals and a horizontal axis representing communal goals and eight octants (Locke, 2003; Trucco et al., 2013). Agentic goals reflect a high value placed on status, respect and dominance, whereas communal goals reflect a high value placed on belongingness and closeness to one's social networks (Ojanen et al., 2005). These goals are particularly relevant in adolescence as this is a period of increased interest in and focus on close interpersonal ties with peers (Collins and Steinberg, 2006). Moreover, adolescence is a period where youth strive for independence from parents and focus on achieving mastery and competence that will bring adult privileges and status (Collins and Steinberg, 2006). The nature of agentic and communal goals suggests that they may impact the salience of descriptive and injunctive norms, and hence conformity to these norms.

Our prior work has provided some initial support for social goals moderating the influence of social norms on intentions to drink alcohol. Authors (2010) found that social norms were stronger predictors of intentions to drink for adolescents with high levels of communal goals. This study, however, was limited by examining intentions to drink in early adolescence using a cross-sectional design, and by combining descriptive and injunctive norms into a composite score. We look to extend this work by assessing the moderational role of social goals separately for descriptive and injunctive norms with a longitudinal design spanning early to middle adolescence. Moreover, the outcome of interest is alcohol use, rather than intentions to drink.

Social Goals and Social Norms: A Moderational Model

During adolescence, increased time and effort is spent on peer relationships and adolescents become increasingly attentive to the opinions of their peers as well as sensitive to peer approval (Collins and Steinberg, 2006; Steinberg, 2008). The increased focus on the peer context during adolescence is thought to increase the salience of both social norms and the potential impact of social goals during this developmental time period (Cialdini and Trost, 1998; Authors, 2013). There is evidence that youth are particularly susceptible to peer influence during early adolescence (Elek et al., 2006; Steinberg, 2008). If adolescents view drinking as a means of obtaining their desired social goals (e.g. helping them gain status and power or gain approval and peer closeness), then they may be particularly motivated to conform to the drinking norms of their peers. Indeed, the Focus Theory of Normative Conduct argues that adolescents may be particularly motivated to conform to social norms if they expect social rewards (Cialdini and Trost, 1998). However, social rewards vary ranging from increased closeness to high social status, and adolescents may be inclined to align their behavior to drinking norms that they believe will achieve their social goals.

Research on drinking prototypes suggests that adolescent drinkers are popular, admired, and respected by their peers in part because they are engaging in an adult behavior and have the appearance of achieving adult status (Allen et al., 2005; Balsa et al., 2011; Gerrard et al., 2002). Because drinking is associated with popular status during this developmental period, adolescents with strong agentic goals may view alcohol as a means of obtaining or retaining the status and power they desire. Considering the power and status associated with drinking during adolescence, strong agentic goals may motivate youth to conform to perceived drinking behavior of peers as doing so aligns with their social goals of status and power. Indeed, evidence suggests that popular adolescents engage in a variety of risky behaviors to maintain their high social status and that they tend to engage in behaviors that are established in the peer group (Allen et al., 2005; Ojanen and Nostrand, 2014).

In contrast to youth who value power and status in their peer relationships (high agentic goals), adolescents with high communal goals value acceptance and closeness to their peer group. Although awareness of and interest in approval of peers increases during adolescence (Kiefer and Ryan, 2011), these changes are especially pronounced among youth with high communal goals (Ojanen et al., 2005; Ojanen and Nostrand, 2014). Hence, injunctive norms, because they emphasize approval rather than descriptive norms, are likely to motivate drinking among youth high in communal goals.

Grade as a Moderator

In prior work, we have found that that agentic and communal goals increase with age (Authors, 2014) suggesting that the moderational effects of social goals on social norms may become stronger in later grades. Additionally, there has been a small body of work suggesting that the effects of social norms on drinking behaviors may vary with age (Salvy et al., 2014). Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of considering grade when assessing the moderational effects of social goals on social norms.

Current Study

The current study tested whether individual differences in social goals influenced the strength of the association of descriptive and injunctive norms with the increased likelihood of adolescent alcohol use using a longitudinal design. We hypothesized that descriptive norms would have a stronger prospective association with alcohol use for individuals high in agentic goals and that injunctive norms would have a stronger prospective association with alcohol use for individuals high in communal goals. Grade was tested as a potential moderator of social norms and was expected to enter into a three-way interaction with social norms and social goals, such that our hypothesized social goal by norms interactions would be stronger at later grades. We also tested gender as a potential moderator in preliminary models because there is some evidence that descriptive and injunctive norms may operate differently for males and females (Elek et al., 2006; Larimer, et al., 2004; Neighbors et al., 2008). However, no a priori hypotheses were made with respect to gender because findings regarding gender differences have been inconsistent (Elek et al., 2006; Voogt et al., 2013).

Materials and Methods

Participants

The current sample was drawn from a longitudinal study investigating the initiation and escalation of adolescent substance use. A community sample was recruited using random-digit dialing (RDD) procedures and both listed and unlisted telephone numbers. RDD was particularly well suited for the current study considering 98.5% of households in sampling frame (Erie County, NY) have a landline. For more information about recruitment procedures and eligibility criteria see Authors (2014).

The current study utilized data from Waves one through four (W1-W4) of the longitudinal project. There was some attrition, and the sample at W1 through four included 387, 373, 370, and 363 families, respectively. The average age of participants was 11.6 at W1, 12.6 at W2, 13.6 at W3, and 15.08 at W4. The sample was approximately evenly split on gender (55% female at W1) and the sample was predominantly non-Hispanic Caucasian (83.1%), and African American (9.1%).

Overall attrition across the three waves was 6.2%. Chi-square and ANOVA analyses were conducted using data from the first assessment to determine whether there was differential attrition over time. No significant differences between participants who completed all interviews and those with missing data were found for race (Χ2[1, N=386]=1.94, p=0.16), gender (Χ2[1, N=387]=0.60, p=0.44), age (F[1, 385]=0.44, p= 0.51), descriptive norms (F[1, 385]=0.14, p=0.71), injunctive norms (F[1,385]=0.22, p=0.64), lifetime alcohol use (Χ2[1, N=386]=0.05, p=0.82), parental education (Χ2[1, N=387]=0.10, p=0.75), marital status (Χ2[1, N=387]=2.17 p=0.14), or family income (F[1, 361]=1.44, p=0.23). This lack of differences and our data analytic approach (full information maximum likelihood estimation), which permitted inclusion of cases with missing data, suggest that missing data likely had a limited impact on our findings.

Procedures

Interviews at W1-W3 were conducted annually in university research offices. Transportation was provided for families (1 caregiver and 1 adolescent) upon request. Before beginning the interviews research assistants obtained consent from caregivers and assent from adolescents. Research assistants interviewed caregivers and adolescents in separate rooms to enhance privacy. Data collection involved the administration of behavioral tasks evaluating different cognitive abilities as well as computer administered questionnaires assessing a wide range of family, peer, and individual level risk and protective factors for the initiation and escalation of adolescent substance use. Families were compensated $75, $85 and $125 dollars for W1, W2 and W3 respectively and adolescents were given a small prize between $5 and $15 at each wave.

W4 consisted of a brief telephone administered audio-Computer Assisted Self Interview (CASI) of substance use that took 10-15 minutes to complete and was conducted 18 months after the W3 assessment. Parents provided consent over the phone and were given a phone number and PIN for their adolescent to use. Assent from the adolescent was obtained at the initiation of the audio-CASI survey.

Measures

Alcohol use (W1-W4)

Items from The National Youth Survey (NYS; Elliott and Huizinga, 1983) were used to assess past year alcohol use. Adolescents reported both the frequency and quantity of their alcohol use without parental permission in the past year. Drinking with parental permission at the ages of our assessments typically occurs in highly structured settings, where parents are supervising their children, such as family celebrations and religious ceremonies (Donovan and Molina, 2008). Thus, alcohol use with parental permission for early adolescents represents a different phenomenon than drinking without parental permission.

As would be expected given the age of our sample, rates of alcohol use were low and suggestive of the early stages of initiation and experimentation. Rates of past year alcohol use were 4.15%, 14.75%, 27.37% and 34.51% for W1-W4, respectively. Considering the low rates of use in our sample, both the quantity and the frequency of alcohol use were highly skewed, and accordingly, responses were dichotomized to indicate past year alcohol use (1) and no past year alcohol use (0). Although it is difficult to compare the rates of our sample to other studies, considering the age of our sample and our assessment of drinking without parental permission, our rates of use are comparable to those found in other studies. The Monitoring the Future Study (MTF) assesses past year alcohol use in a nationally representative sample of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders. MTF found rates of past year alcohol use of 29.30% in 8th grade and 52.10% in 10th grade (Johnston et al., 2010), compared to 15.84% in 8th grade and 35.50% in 10th grade in our sample. The lower rates seen in our sample are likely attributable to MTF not distinguishing between use with and without parental permission. King et al. (2004) found lifetime rates of alcohol use without parental permission in 11 and 14 year olds for their twin study (N=1,354) to be 2% and 31%, respectively. These lifetime rates are comparable to rates seen in our sample (2.41% and 27.01%, respectively). In sum, when accounting for differences in methods of assessing alcohol use in adolescence, our rates are comparable to other studies of the same developmental period.

Social Norms (W1-W3)

Descriptive and injunctive norms were each assessed with three items from the Monitoring the Future Study (Johnston et al., 2003). The descriptive norms items asked participants to report how many of their friends (1) drink occasionally, (2) drink regularly, and (3) consume more than 5 drinks during a single drinking occasion using six response options (1=none to 6=all). Injunctive norms were assessed with three items asked participants to rate how their 3 close friends would feel about them doing each of the following behaviors (1) drinking alcohol occasionally, (2) drinking alcohol regularly, and (3) having 5 or more drinks of alcohol at one time using a 5-point response scale (1=strongly disapprove to 5=strongly approve). The internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) for descriptive norms was .85, .90, and .87 at W1, W2 and W3, respectively, and .86, .89, and .91 for injunctive norms.

Social Goals (W1-W3)

Social goals were assessed with the Interpersonal Goals Inventory for Children Revised (IGI-CR; Trucco et al., 2013). The IGI-CR has been shown to fit a circumplex (Trucco et al., 2013; Authors, 2014) and has demonstrated strong convergent validity (Trucco et al., 2013). The IGI-CR is comprised of 32 items all containing the prompt, “When with your peers, in general how important is it to you that...?” Responses are on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all important to me) to 4 (extremely important to me). The IGI-CR is comprised of 8 octants containing 4 items each. The octants are Agentic (appearing dominant, independent), Agentic-Separate (appearing to have the upper hand and getting even), Separate (appearing detached and not disclosing thoughts and feelings to others), Submissive-Separate (appearing distant and avoiding rejection from others), Submissive (going along with peers to avoid arguments or upsetting others), Submissive-Communal (putting others’ needs first, valuing approval from others), Communal (valuing solidarity with peers and belongingness), and Agentic-Communal (expressing oneself openly, being respected). Vector scores were computed to represent agentic and communal goals using formulas commonly used by social goals researchers (Locke, 2003; Ojanen et al., 2005).

Data Analytic Strategy

Multilevel logistic regression was used to assess cross-lagged associations between descriptive and injunctive norms and alcohol use using the PROC GLIMMIX procedure in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., 2011) with maximum likelihood estimation (ML). The two-level model included repeated measures nested within participant. The models were set up to test cross-lagged effects (W1 social goals and norms predicting W2 alcohol use controlling for W1 alcohol use, W2 social goals and norms predicting W3 alcohol use controlling for W2 alcohol use, etc.). Grade was treated as a time-varying covariate. The model included a random intercept. Interaction terms with gender and grade were tested as a block in separate models using a nested model chi-square test. Predictor variables were standardized within grade to reduce non-essential multicollinearity and facilitate interpretation of the interaction effects (Hox, 2002).

Results

Correlations

Point-biserial correlations were computed between alcohol use and communal and agentic social goals as well as descriptive and injunctive norms. The relationship between descriptive norms and alcohol use (6th grade: r=.20, 7th grade: r=.23, 8th grade: r=.43, 9th grade: r=.48) as well as injunctive norms and alcohol use (6th grade: r=.19, 7th grade: r=.27, 8th grade: r=.47, 9th grade: r=.47) increased with grade. No systematic associations were observed between agentic goals and alcohol use (6th grade: r=.02, 7th grade: r=.17, 8th grade: r=.04, 9th grade: r=.11) and the strength of the association between communal goals and alcohol use decreased with grade (6th grade: r=.22, 7th grade: r=.13, 8th grade: r=.04, 9th grade: r=.−.03).

Multilevel Models

The gender interaction terms did not significantly improve model fit (Χ2 [8, N=386]=5.16, p>.05), and were not considered further. However, the first-order effect of gender was included as a statistical control variable in models testing grade interaction terms.

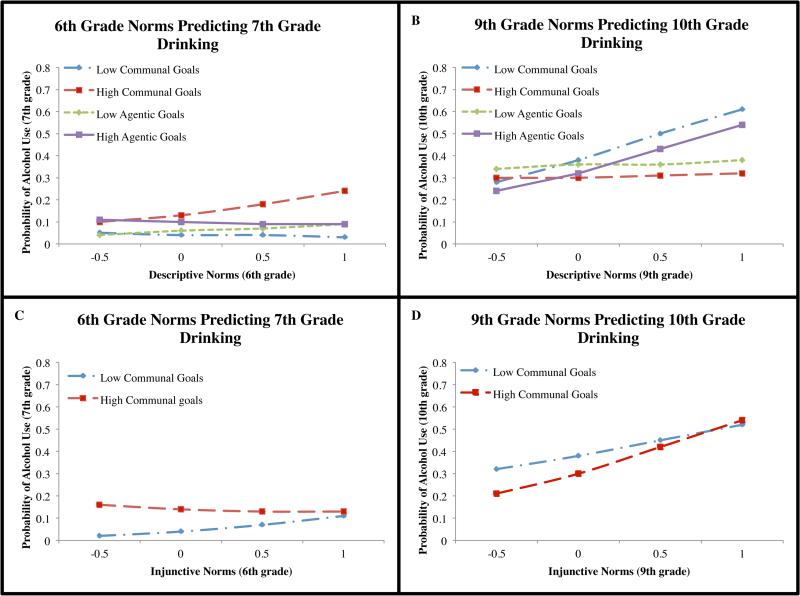

A nested chi-square test comparing a model with and without the hypothesized interaction terms with grade suggested that model fit improved with the inclusion of twoway (Χ2 [8, N=386]=18.25, p<.05) and three-way (Χ2 [4, N=386]=11.21, p<.05) interactions. As shown in Table 1, significant three-way interaction terms were found for grade × descriptive norm × communal goals (B =−0.33, p=.03), grade × injunctive norms × communal goals (B =0.30, p=.03), and grade × descriptive norms × agentic goals (B=0.24, p=.04). The grade × injunctive norms × agentic goals three-way interaction term was not statistically significant (B =−0.15, p=.30). To facilitate interpretation of the three-way interaction terms, simple slopes of norms by levels of social goals were plotted for an early (6th variables predicting 7th grade alcohol use) and late (9th grade variables predicting 10 grade alcohol use) cross-lag (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Hierarchical Logistic Regression results (unstandardized regression coefficients)

| Variable | B | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.53** | 0.24 |

| Prior alcohol use | 0.79** | 0.27 |

| Gender | −0.05 | 0.21 |

| Grade | 0.62** | 0.11 |

| Descriptive Norm (DN) | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| Injunctive Norm (IN) | 0.40 | 0.24 |

| Communal Goals (CG) | 0.65** | 0.19 |

| Agentic Goals (AG) | 0.32 | 0.21 |

| IN × CG | −0.67** | 0.26 |

| DN × CG | 0.52 | 0.30 |

| IN × AG | 0.21 | 0.28 |

| DN × AG | −0.34 | 0.22 |

| Grade × DN | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| Grade × IN | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Grade × CG | −0.27** | 0.10 |

| Grade × AG | −0.12 | 0.11 |

| Grade × DN × CG | −0.33* | 0.15 |

| Grade × IN × CG | 0.30* | 0.13 |

| Grade × DN × AG | 0.26* | 0.13 |

| Grade × IN × AG | −0.15 | 0.14 |

Note. DN=descriptive norms, IN=injunctive norms, CG=communal goals, AG=agentic goals.

p<.05

p<.01.

Figure 1.

Simple slopes of three-way interactions. Panels A and B depict simple slopes for the Grade × Descriptive Norms × Agentic/Communal Goal interaction and Panels C and D depict simple slopes for the Grade × Injunctive Norms × Communal Goals interaction.

Descriptive Norms

Descriptive Norms and Agentic Goals

As seen in Panel A of Figure 1, for adolescents in the 6th grade, descriptive norms were not found to significantly predict 7th grade alcohol use for adolescents with high or low levels of agentic goals (OR=0.86 and 1.71, respectively, both ps>.05). High levels of descriptive norms in the 9th grade were associated with increased probability of alcohol use in the 10th grade for adolescents with high (OR=2.43 p<.05), but not low (OR=1.09, p>.05) levels of agentic goals. This pattern provides partial support for the hypothesized interaction between descriptive norms, agentic goals and grade. That is, there was a shift in the moderating role of agentic social goals with grade, such that descriptive norms became a predictor of alcohol use for youth characterized by strong agentic goals, but only in later grades.

Descriptive Norms and Communal Goals

High levels of descriptive norms in the 6th grade were associated with increased probability of alcohol use in the 7th grade for adolescents characterized by high (OR=2.07, p<.05) but not low (OR=0.72, p>.05) levels of communal goals. As seen in Panel 2 of Figure 1, in later grades, this pattern reversed itself, such that 9th grade descriptive norms were not associated with 10th grade drinking for adolescents high in communal goals (OR=0.72, p>.05), but they were associated with 10th grade drinking for adolescents low in communal goals (OR=2.58, p>.05). Although descriptive norms were not hypothesized to interact with communal goals, these findings suggest a developmental shift such that in early adolescence, descriptive norms influence alcohol use for those characterized by strong communal goals whereas in later adolescence descriptive norms influence alcohol use for adolescents characterized by weak communal goals.

Injunctive Norms

Injunctive Norms X Communal Goals

As depicted in Panel C of Figure 1, 6th grade injunctive norms were associated with increased probability of alcohol in 7th grade alcohol use for adolescents with low (OR=2.91, p<.05), but not high (OR=0.76, p>.05) levels of communal goals. Moving to later adolescence, high levels of injunctive norms in 9th grade were associated with increased probability of alcohol use in 10th grade for adolescents with both low (OR=1.80, p>.05) and high (OR=2.68, p>.05) levels of communal goals. This pattern suggests that injunctive norms take on increasing importance in later adolescence across the spectrum of communal goals. These findings provide partial support for the hypothesized interaction between injunctive norms, high communal goals and grade but also contradict our hypotheses such that high levels of injunctive norms and low levels of communal goals predicted higher levels of alcohol use in later adolescence.

Discussion

Although social norms are robust predictors of adolescent alcohol use (Borsari and Carey, 2001; Perkins, 2002), theoretical formulations suggest that the impact social norms have on behavior varies depending on their salience. Few studies have examined potential mechanisms that may make social norms more or less salient to influence adolescent early drinking. The current study looked to elucidate moderating factors that might impact the strength of association between social norms on adolescent early alcohol use. Specifically, agentic and communal social goals were tested as moderators of the association between descriptive and injunctive norms and alcohol use across early to middle adolescence. Findings supported the moderating role of social goals, but the effects depended on grade.

Partial support was found for our hypothesis that descriptive norms would be a stronger predictor of alcohol use for adolescents with high levels of agentic goals. Perceptions of peer alcohol use (descriptive norms) were not prospectively associated with 7th grade alcohol use for adolescents with either low or high agentic goals. However, in later adolescence, descriptive norms came to be prospectively associated with 10th grade alcohol use for individuals characterized by high levels of agentic goals, suggesting that the moderating influence of agentic goals do not emerge until later adolescence. Several lines of evidence suggest that adolescence who value status and power (high agentic goals) may conform to peer drinking norms as a means to obtain or maintain social standing. Recent work suggests that alcohol use is linked to popular status, especially in later adolescence (Allen et al., 2005; Balsa et al., 2011). Moreover, there is evidence that popular peers are particularly susceptible to peer social norms because they are highly attuned to the behaviors of their peers and motivated to maintain their social status (Allen et al., 2005; Cillessen and Mayeux, 2004). These dynamics are likely not limited to alcohol use as evident by studies showing that popularity and high agency are associated with a wide variety of risk behavior (Mayeux et al., 2008; Markey et al., 2005).

Contrary to our hypotheses, descriptive norms were prospectively associated with 7th grade alcohol use for adolescents with high levels of communal goals. However, by 10th grade, injunctive, but not descriptive norms were prospectively associated with alcohol use for these adolescents. This pattern suggests a developmental shift such that youth characterized by high communal goals are likely to conform to descriptive alcohol norms in early adolescence and then to injunctive norms later in adolescence. We expected that youth with strong communal goals would be motivated to conform to peer approval of drinking (injunctive norms) to maintain close social ties. However, why conformity to descriptive norms was evident in early adolescence is unclear. Approval of drinking during early adolescence is fairly low (Jackson et al., 2014; Voogt et al., 2013), yet adolescents (even in early adolescence) view the prototypical drinker as someone who is gregarious, social, and fits in (Norman et al., 2007). In the absence of approval in early adolescence, youth with strong communal goals may conform to descriptive norms to maintain or form social ties. However, in later adolescence when alcohol becomes more common and attitudes about alcohol become more positive (Colder et al., 2014) injunctive norms may become of the more salient guide of drinking behavior.

Descriptive and injunctive norms were found to be prospectively associated with alcohol use in 10th grade for adolescents with low levels of communal goals. These findings were surprising. Social norms were not hypothesized to be associated with alcohol use for adolescence low in communal goals because these individuals are typically described as being socially detached (Ojanen et al., 2005). Moreover, weak communal goals are associated with high levels of social anxiety, shyness, social avoidance and unsociability (Authors, 2008), suggesting that these youth might be isolated from social contexts that promote drinking. However some research suggests that although adolescents with low communal goals are socially detached and rejected by their peers, they may still desire peer relationships (Ojanen et al, 2005; Authors, 2008). Additionally, work from developmental neuroscience suggests that there is an increased desire to have peer interactions during pubertal development, perhaps, as a result of maturation of neural circuitry that make these interactions more rewarding (Steinberg, 2007). Indeed, one of the notable transitions during adolescence is a shift toward spending increasing amounts of time with peers (Spear, 2000). Taken together, these findings suggest that despite their desire for emotional distance, adolescents low in communal goals may desire social ties and may look at social norms of drinking as a means of meeting their conflicting desire for emotional distance and social connectedness.

Limitations

Although the current study had several strengths including its longitudinal design spanning early to middle adolescence and its assessment of unique moderating mechanisms of descriptive and injunctive norms, it is important to note several limitations. First, our study spanned early to middle adolescence, and consequently our findings are most generalizable to the early stages of alcohol use (initiation and experimentation). Additionally, while descriptive and injunctive norms have been shown to be largely inaccurate in later adolescence (Borsari and Carey, 2003), few studies have assessed the accuracy of descriptive norms in early and middle adolescents (Henry et al., 2011) and none have assessed the accuracy of injunctive norms during this developmental period. Moreover, considering the low rates of use during this developmental period, we were limited to looking at the prevalence of adolescent drinking rather than the frequency of adolescent use. Future work would benefit from extending the current study to other developmental periods, such as young adults and college students, to test if our moderational findings are replicated at older ages and when using frequency and quantity outcomes. Second, social norms are necessarily keyed to a referent group, and in our study these included friends and close friends. There is a large literature demonstrating that as referents become more distal, there is a weaker association between norms and drinking behaviors (Collins and Spelman, 2013; Neighbors et al., 2008). Hence, our moderational findings may not generalize to social norms assessed using other more distal referents (e.g., someone your age and gender). Third, we did not measure the actual alcohol use and social goals of our participants’ peers in the current study. Selection effects have been well established in the adolescent drinking literature and recent work has suggested that adolescents may select into peer groups with similar social goals (Burk et al., 2012; Ojanen et al., 2013). We can't determine selection effects with our data. Identifying the role of selection effects in our moderational model using social network data would be an important direction for future research.

Despite these limitations, the current study makes an important contribution to the literature by elucidating specific moderating mechanisms through which descriptive and injunctive norms influence alcohol use. This work adds to limited number of studies assessing social norms from a developmental perspective and adds to body of work looking to understand for whom and when social norms impact behavior. Normative feedback interventions, which provide adolescents with accurate information regarding the drinking behaviors of their peers, have been widely used to combat adolescent and college student drinking (Perkins, 2002; Walters and Neighbors, 2005). Despite their widespread implementation, these interventions have had mixed efficacy (Schultz et al., 2007). Results from the current study suggest that normative feedback interventions may benefit from being tailored based on an individual's grade and social goals. For instance, personalized normative feedback for older adolescents (9th graders) with high agentic goals may be more successful if they target descriptive drinking norms, whereas, personalized normative feedback for older adolescents (9th graders) with high communal goals may be more successful if they target injunctive drinking norms.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA019631) awarded to Dr. Craig R. Colder.

References

- Allen JP, Porter MR, McFarland FC, Marsh P, McElhaney KB. The two faces of adolescents' success with peers: Adolescent popularity, social adaptation, and deviant behavior. Child Dev. 2005;76:747–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Authors 2008. [Citation omitted for review]

- Authors 2010. [Citation omitted for review]

- Authors 2014. [Citation omitted for review]

- Balsa AI, Giuliano LM, French MT. The effects of alcohol use on academic achievement in high school. Econ Educ Rev. 2011;30:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa AI, Homer JF, French MT, Norton EC. Alcohol use and popularity: Social payoffs from conforming to peers' behavior. J Res Adolescence. 2011;21:559–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. Adolescents’ time use: Effects on substance use, delinquency, and sexual activity. J Youth Adolescence. 2007;36:697–710. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. J Stud Alc. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk WJ, Van Der Vorst H, Kerr M, Stattin H. Alcohol use and friendship dynamics: Selection and socialization in early-, middle-, and late-adolescent peer networks. J Stud Alcohol Drug. 2012;73:89–98. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58:1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:591–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Trost MR. Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. 4 ed. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AH, Mayeux L. From censure to reinforcement: developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Dev. 2004;75:147–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Campbell RT, Ruel E, Richardson JL, Flay BR. A finite mixture model of growth trajectories of adolescent alcohol use: Predictors and consequences. J Consult Clin Psych. 2002;70(4):976–985. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, O'Connor RM, Read JP, Eiden RD, Lengua LJ, Hawk LW, Jr, Wieczorek WF. Growth trajectories of alcohol information processing and associations with escalation of drinking in early adolescence. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28:659–770. doi: 10.1037/a0035271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Spelman PJ. Associations of descriptive and reflective injunctive norms with risky college drinking. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27:1175–1181. doi: 10.1037/a0032828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Steinberg L. Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology (551-578) John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Molina BSG. Children's introduction to alcohol use: Sips and tastes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;21:108–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elek E, Miller-Day M, Hecht ML. Influences of personal, injunctive, and descriptive norms on early adolescent substance use. J Drug Issues. 2006;36:147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D. Social class and delinquent behavior in a national youth panel. Criminology. 1983;21:149–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Graham JW, Maguin E, Abott R, Hill KG, Catalano RF. Exploring the effects of age of alcohol initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:280–290. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Kobus K, Schoeny ME. Accuracy and bias in adolescents' perceptions of friends' substance use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:80–89. doi: 10.1037/a0021874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, White HR, Chung IC, Hawkins D, Catalano RF. Early adult outcomes of adolescent binge drinking: Person- and variable-centered analyses of binge drinking trajectories. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:892–902. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox JJ. Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson RP, Mortensen CR, Cialdini RB. Bodies obliged and unbound: Differentiated response tendencies for injunctive and descriptive social norms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;100:433–448. doi: 10.1037/a0021470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Roberts ME, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Abar CC, Merrill JE. Willingness to drink as a function of peer offers and peer norms in early adolescence. J Stud Alcohol Drug. 2014;73:404–414. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG. Volume I: Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 03-5375) National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2003. Monitoring the future: national survey results on drug use, 1975-2002. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2009 (NIH Publication No. 10-7583) National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99:1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:203–212. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke K. Status and solidarity in social comparison: Agentic and communal values and vertical and horizontal directions. J of Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:619–631. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markey PM, Markey CN, Tinsley B. Applying the interpersonal circumplex to children's behavior: Parent-child interactions and risk behaviors. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2005;31:549–559. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux L, Sandstrom MJ, Cillessen AH. Is being popular a risky proposition? J Res Adolescence. 2008;18:49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, O'Connor RM, Lewis MA, Chawla N, Lee CM, Fossos N. The relative impact of injunctive norms on college student drinking: The role of reference group. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:576–581. doi: 10.1037/a0013043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman P, Armitage CJ, Quigley C. The theory of planned behavior and binge drinking: Assessing the impact of binge drinker prototypes. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1753–1768. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojanen T, Grönoos M, Salmivalli C. An interpersonal circumplex model of children's social goals: Links with peer-reported behavior and sociometric status. Dev Psych. 2005;5:699–710. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojanen T, Findley-Van Nostrand D. Social goals, aggression, peer preference, and popularity: Longitudinal links during middle school. Dev Psych. 2014;50:2134–2143. doi: 10.1037/a0037137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojanen T, Sijtsema JJ, Rambaran JA. Social goals and adolescent friendships: Social selection, deselection, and influence. J Res Adolescence. 2013;23:550–562. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;14:164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Davidoff OJ, McLacken J, Campbell JF. Making the transition from high school to college: The role of alcohol-related social influence factors in students' drinking. J Subst Abuse. 2002;23(1):53–65. doi: 10.1080/08897070209511474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvy SJ, Pedersen ER, Miles JN, Tucker JS, D'Amico E J. Proximal and distal social influence on alcohol consumption and marijuana use among middle school adolescents. Drug Alcohol Dep. 2014;144:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS (Version 9.3) [Computer software] Author; Cary, NC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz PW, Nolan JM, Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ, Griskevicius V. The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychol Sci. 2007;18:429–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence new perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci BioBehav R. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teunissen HA, Spijkerman R, Prinstein MJ, Cohen GL, Engels RC, Scholte RH. Adolescents’ conformity to their peers’ pro-alcohol and anti-alcohol norms: The power of popularity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:1257–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Colder CR, Wieczorek WF. Vulnerability to peer influence: A moderated mediation study of early adolescent intentions to drink. Addict Behav. 2011;36:729–736. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Wright AG, Colder CR. A Revised Interpersonal Circumplex Inventory of Children's Social Goals. Assessment. 2013;20:98–113. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voogt CV, Larsen H, Poelen EAP, Kleinjan M, Engles RCME. Longitudinal associations between descriptive and injunctive norms of youngsters and heavy drinking and problem drinking in late adolescence. J Subst Use. 2013;18:275–287. [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Neighbors C. Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: What, why and for whom? Addict Behav. 2005;30:1168–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]