Abstract

Neuroimaging research has implicated abnormalities in cortico-striatal-thalamic-cortical (CSTC) circuitry in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). In this study, resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (R-fMRI) was used to investigate functional connectivity in the CSTC in adolescents with OCD. Imaging was obtained with the Human Connectome Project (HCP) scanner using newly developed pulse sequences which allow for higher spatial and temporal resolution. Fifteen adolescents with OCD and 13 age- and gender-matched healthy controls (ages 12-19) underwent R-fMRI on the 3T HCP scanner. Twenty-four minutes of resting-state scans (two consecutive 12-minute scans) were acquired. We investigated functional connectivity of the striatum using a seed-based, whole brain approach with anatomically-defined seeds placed in the bilateral caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens. Adolescents with OCD compared with controls exhibited significantly lower functional connectivity between the left putamen and a single cluster of right-sided cortical areas including the orbitofrontal cortex, inferior frontal gyrus, insula, and operculum. Preliminary findings suggest that impaired striatal connectivity in adolescents with OCD in part falls within the predicted CSTC network, and also involves impaired connections between a key CSTC network region (i.e., putamen) and key regions in the salience network (i.e., insula/operculum). The relevance of impaired putamen-insula/operculum connectivity in OCD is discussed.

Keywords: Functional MRI, Neuroimaging, Striatum, Insula, Operculum

1. INTRODUCTION

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a debilitating disorder with a lifetime prevalence rate of approximately 2.7% (Ruscio et al., 2010; Kessler et al., 2012). Neuroimaging research has implicated cortico-striatal-thalamic cortical (CSTC) circuitry in OCD (Huyser et al., 2009). These networks connect neurons in the cortex, striatum (i.e., caudate, putamen, nucleus accumbens), thalamus, and back to the cortex (Alexander et al., 1986; Maia et al., 2008; Kalra and Swedo, 2009). Theory suggests that abnormalities in the CSTC result in the obsessions and compulsions of pediatric OCD (Kalra and Swedo, 2009). In addition to the CSTC, other networks and brain regions appear to be involved in OCD (Menzies et al., 2008; Fitzgerald et al., 2010; Jang et al., 2010; Milad and Rauch, 2012).

Advances in neuroimaging that assess brain connectivity allow for a sophisticated understanding of neural networks. Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (R-fMRI) assesses the spontaneous slow-wave fluctuations of blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals between brain areas at rest (Biswal et al., 1995). Functional connectivity is determined by inter-regional correlations of these temporal patterns (Fox and Raichle, 2007). There have been a number of resting-state studies of OCD (Harrison et al., 2009; Fitzgerald et al., 2010; Jang et al., 2010; Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Sakai et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012; Beucke et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2013; Gruner et al., 2014; Weber et al., 2014), but only four have been in children and adolescents (Fitzgerald et al., 2010; Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Gruner et al., 2014; Weber et al., 2014).

R-fMRI studies in adults show interesting findings in whole brain analyses using striatal seeds. Harrison and colleagues (2009) found reduced functional connectivity between the dorsal striatum and the lateral prefrontal cortex and between the ventral striatum and the midbrain ventral tegmental area in 21 adults with OCD (most were medicated) compared with 21 matched healthy controls. They also found increased functional connectivity in adults with OCD between the ventral caudate/accumbens and the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and surrounding areas. Similar to Harrison et al., Sakai and associates (2011) found significantly greater functional connectivity between the ventral striatum and the frontal cortex in 20 medication-free adults with OCD compared with 23 matched healthy controls. Our seeds included the seeds in Harrison et al. (2009) and Sakai et al. (2011).

Buecke and colleagues (2013) evaluated resting-state functional connectivity in both medicated and unmedicated adults with OCD and healthy controls. Data were analyzed using a graph theory approach in contrast with previous studies that used a whole brain seed-based approach. This study found significantly greater distant connectivity in the OFC and subthalamic nucleus in the unmedicated OCD group compared with healthy controls. Buecke et al. defined distant connectivity to be connectivity to any brain regions that was more than 12 mm from the OFC (or subthalamic nucleus). The study also reported greater local connectivity in the OFC and putamen in unmedicated OCD patients compared with healthy controls.

Given that OCD may have a neurodevelopmental etiology and that the networks of interest in OCD undergo considerable refinement throughout childhood and adolescence (Huyser et al., 2009), examination of OCD circuitry in youth is critical. Fitzgerald and colleagues (2010) found deceased connectivity between the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and right anterior operculum and between the ventral medial frontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) in youths with OCD (n = 18) compared with matched healthy controls (n = 18). Twelve of the OCD participants were on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Subsequently, Fitzgerald et al. (2011) examined resting-state functional connectivity between OCD and controls in four developmental age groups: children (8-12 years) (n = 11), adolescents (13-17) (n = 18), young adults (18-25) (n = 18), and older adults (26-40) (n = 13). Half of the OCD participants were on psychotropic medications. The seeds in Fitzgerald and colleagues’ study (2011) (i.e., dorsal striatum) overlapped with seed placement in the current study. Across all age groups, OCD patients compared with controls showed greater connectivity between ventral medial frontal cortex and dorsal striatum. However, only children with OCD showed significantly lower connectivity between rostral ACC and dorsal striatum, and between dorsal ACC and medial dorsal thalamus. Lower connectivity in the rostral ACC-dorsal striatum connection was associated with greater severity on the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) (Scahill et al., 1997). The findings suggest that developmental stage affects the pathophysiology of the disorder.

To date, R-fMRI studies show contrasting findings regarding whether CSTC connections in OCD patients are hypoconnected (Jang et al., 2010; Posner et al., 2013), hyperconnected (Sakai et al., 2011; Beucke et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2013), or both (Harrison et al., 2009; Fitzgerald et al., 2011). The current pilot study was designed to address some of the gaps in the literature with respect to resting-state functional connectivity in OCD. Our study investigated pediatric OCD and used advanced acquisition schemes that were developed at our University as part of the NIH-funded Human Connectome Project (HCP) to enable collection of fMRI data at much higher temporal and spatial resolution than has been standard (Feinberg et al., 2010; Moeller et al., 2010). While previous OCD studies collected data over short time periods (i.e., 4 to 8 minutes) (e.g., Harrison et al., 2009; Jang et al., 2010; Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Sakai et al., 2011), this study evaluated connectivity over 24 minutes. Lastly, we employed rigorous methods to minimize regions of interest (ROI) registration errors and to correct for confounds due to motion (Power et al., 2012).

In the current study, we viewed the striatal areas (caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens) as key central regions within the CSTC to interrogate this network in adolescents with and without OCD. It was hypothesized that adolescents with OCD would show abnormalities in functional connectivity in the CSTC (i.e., between caudate/putamen/nucleus accumbens and other regions within this network, e.g., frontal cortex, thalamus) when compared with healthy controls, as measured by R-fMRI.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

Seventeen adolescents with OCD ages 12-19 years and 13 age- and gender-matched healthy controls were enrolled. Inclusion Criteria for OCD participants: OCD as the primary DSM-IV diagnosis based on Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS) for DSM-IV, Child Version (Silverman and Albano, 1996). Exclusion Criteria: Lifetime diagnosis of autism/pervasive developmental disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or substance abuse/dependence on ADIS, IQ < 80 on Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence (WASI) (Wechsler, 1999), positive urine drug screen or pregnancy test, and MRI-incompatible features (e.g., metal implants, claustrophobia).

2.2. Procedure

The study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited from the Child and Adolescent Anxiety Disorders Clinic at our University, area clinics, newspapers, Craig's List and Facebook advertisements, and community postings. After written informed consent and assent were obtained, trained interviewers administered a 2-3 hour diagnostic assessment. Participants underwent neuroimaging at the Center for Magnetic Resonance Research and received monetary compensation for participation.

2.3. Assessment Instruments

(1) ADIS was used to confirm OCD diagnosis (Silverman et al., 2001; Wood et al., 2002). (2) Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) and Checklist is a clinician-rated semi-structuredinstrument to assess severity and types of obsessions and compulsions (Scahill et al., 1997). It has good inter-rater reliability and validity (Storch et al., 2006). (3) Yale Global Tic Severity Scale was used to evaluate severity of comorbid tics (Leckman et al., 1989). (4) Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale – Revised (COIS-R), Parent Version and Child Version measured functional impairment due to OCD (Piacentini et al., 2007). (5) WASI provided a measure of cognitive functioning to ensure IQs > 79.

2.4. MRI

Imaging was conducted on the Siemens Skyra 3T Human Connectome scanner (http://www.humanconnectome.org/about/project/MR-hardware.html) using a 32-channel receive only head coil. Anatomic Acquisition: Whole brain anatomical data with T1 contrast were acquired in 5 minutes using an MP-RAGE sequence with 1 mm isotropic resolution (TR = 2530 ms, TE = 3.52 ms, TI = 1100 ms, flip angle = 7 degrees). Processing and Analysis: T1 images were processed using FreeSurfer version 5.1.0 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). Specific FreeSurfer-defined ROIs of the CSTC network (bilateral caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens) were identified.

2.5. R-fMRI Acquisition

Resting-state BOLD data were collected using a novel multi-band EPI pulse sequence that allows for simultaneous acquisition of multiple slices (Feinberg et al., 2010; Moeller et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2013). Two 12-minute consecutive resting scans were acquired. The two consecutive R-fMRI datasets were acquired with identical scan parameters (TR = 1.15 seconds, TE = 30 ms, voxel size = 2 mm isotropic, 60 slices, multiband factor = 4, echo spacing 0.57 ms, 600 volumes) except the first acquisition used anterior to posterior phase encode direction while the second used posterior to anterior phase encode direction. For both resting scans, subjects were instructed to close their eyes, remain awake, and not think about anything in particular. There was a brief pause between first and second scans to verbally confirm that participants were awake. A field map scan with identical voxel parameters to the BOLD acquisition was acquired and used to correct geometric distortion caused by magnetic field inhomogeneity.

2.6. Image Processing

FSL (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/) tools were used to conduct preprocessing steps, including skull removal, distortion correction, motion correction and registration to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space (Mazziotta et al., 1995). The FSL program MELODIC was used to conduct an exploratory independent component analysis (ICA) on the processed functional data for each individual. As part of this process, a 4 mm Gaussian smoothing kernel was applied to the data during the ICA. Following methods described in our previous work (Cullen et al., 2011), the components were inspected with regard to spatial clusters, time series, and power spectra. Components that were most likely to represent artifacts such as heart rate, respiration, or movement, as well as components in white matter or cerebrospinal fluid were removed according to published guidelines (Kelly et al., 2010) using fsl regfilt.

To further remove artifactual correlations due to transient head motion, we utilized the “scrubbing” procedure advocated by Power and colleagues (Power et al., 2012), computing frame-wise displacement (FD) and derivative variance (DVARS) metrics. Because our acquisition parameters and preprocessing methods differed from Power et al. (2012), we determined appropriate volume exclusion values for the specifics of our acquisition. We used the same criterion for volume rejection due to motion as Power and colleagues (FD > 0.5 mm) but because the noise properties of our data were different, we excluded volumes with DVARS > 8 rather than DVARS > 5 used by Power et al. (2012).

2.7. Data Analysis

Two subjects with OCD were excluded. One of these subjects did not complete the scan and a second was excluded during the scrubbing process, yielding a sample size of 15 with OCD and 13 controls. Subject-identified bilateral caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens FreeSurfer ROIs, which are part of the CSTC circuit and implicated in OCD, were selected for investigation. The anatomical data were registered to the functional data using the FSL/FreeSurfer programs bbregister (Greve and Fischl, 2009), an advanced tool that allows for more precise alignment between functional and structural datasets.

Any volume which exceeded the FD and/or DVARS threshold was excluded from analysis, as well as the preceding volume and following two volumes. One OCD subject had more than 33% of the volumes (i.e., greater than 400 of 1200 volumes) rejected during the scrubbing process and was excluded from analysis as noted above. There was no significant difference between the mean number of volumes excluded from scans of OCD subjects (109.33 + 23.31) versus control subjects (134.08 + 49.60) [t(17.17) = 0.45, p = 0.657)]. FD was calculated for the volumes that remained after the scrubbing process. There was no significant difference between the mean FD for OCD subjects (0.13 + .03) and control subjects (0.12 + .03) [t(26) = 0.86, p = 0.397)].

2.8. Functional Connectivity Analysis

Connectivity stemming from the selected ROIs (bilateral caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens) was examined using a seed-based whole-brain approach similar to the methods used by Cullen and colleagues (2014). To enhance the registration of the ROIs to each subject's anatomy, we used FreeSurfer to create individual anatomically-based ROIs. ROIs were aligned to each individual's fMRI data using bbregister and his/her time series was extracted. This was performed separately for the two consecutive twelve-minute resting scans acquired on each subject using FSL FEAT to perform first-level analyses. The time series of each ROI was used as the primary regressor in a general linear model and the lateral ventricle CSF and white matter time course were used as regressors of no interest, each with no temporal derivative, temporal filtering, or convolution. We used a z threshold of 2.3 and cluster corrected p < 0.05. This step also included FILM prewhitening, and registration to MNI standard space for later group-level analyses. The statistical maps from the two resting scans were then combined for each ROI using a second level analysis in FSL FEAT, yielding the final connectivity maps for right and left caudate, right and left putamen, and right and left nucleus accumbens representing the entire 24 minutes of resting data for each person that would be used for the subsequent group analyses.

2.9. Group Analyses

We performed group-level comparisons to examine whole-brain functional connectivity for each ROI. We used a higher-level FEAT analysis to examine the main effect of group using a z-cluster threshold of 2.3 which corresponds to p < 0.0107 and applied a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons by using p < 0.0083 for six ROIs. We extracted z-scores within each of the significant clusters produced by group comparisons using Featquery.

To explore the relations between clinical measures (i.e., CY-BOCS, scores on four dimensions from the CY-BOCS Checklist, COIS-R) and connectivity, we used mean z-scores representing connectivity within the cluster. Correlations were calculated between mean z-scores and clinical measures for the OCD group (n = 15). Significant correlations were determined using p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants

There were no significant differences between the OCD and control groups on age at assessment, gender, socioeconomic status (Hollingshead, 1975), IQ, ethnicity, handedness, or caudate, putamen, or nucleus accumbens volume (Table 1). Mean age of onset of OCD was 9.1 + 4.0 years and mean duration of illness was 5.6 ± 4.1 years. Eighty percent (12 of 15) of OCD participants were on psychotropic medications. Of the 12 who were on an SSRI and/or clomipramine, 4 were also on other medications (Table 1). Mean total CY-BOCS score for OCD group was 19.7 (moderate severity). All urine toxicology and pregnancy tests were negative.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the OCD and control groups

| OCD (n = 15)a | Control (n = 13) | t or χ2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset, mean (SD) | 9.1 | (4.0) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Age at assessment, mean (SD) | 15.3 | (2.1) | 16.0 | (1.8) | t = 0.98 | 0.34 |

| Tanner stageb, mean (SD) | 3.6 | (1.5) | 4.2 | (0.9) | t = 1.1 | 0.27 |

| Male, n (%) | 8 | (53) | 7 | (54) | χ2 = 0.001 | 0.98 |

| SES, mean (SD) | 53.8 | (7.0) | 50.0 | (16.9) | t = 0.80 | 0.43 |

| WASI IQ, mean (SD) | 115.3 | (11.2) | 107.8 | (14.4) | t = 1.55 | 0.13 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | χ2 = 2.86 | 0.24 | ||||

| Caucasian | 13 | (86.7) | 8 | (61.5) | ||

| Latino | 1 | (6.7) | 4 | (30.8) | ||

| Asian | 1 | (6.7) | 1 | (7.7) | ||

| Right handedness, n (%) | 15 | (100) | 12 | (92.3) | χ2 = 120 | 0.27 |

| 1st-degree family history of OCD, n (%) | χ2 = 4.08 | 0.13 | ||||

| Yes | 4 | (26.7) | 0 | (0) | ||

| No | 9 | (60.0) | 11 | (84.6) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | (13.3) | 2 | (15.4) | ||

| Current medications, n (%) | ||||||

| SSRI or clomipramine | 8 | (53.3) | 0 | (0) | ||

| SSRI and/or clomipramine + other psychotropic medication(s) | 4c | (26.7) | 0 | (0) | ||

| Medication-free | 3 | (20.0) | 13 | (100) | ||

| Current comorbidityd, n (%) | ||||||

| Tic disorder | 1 | (6.7) | 0 | (0) | ||

| Social phobia | 3 | (20.0) | 0 | (0) | ||

| ADHD | 6 | (40.0) | 0 | (0) | ||

| ODD | 3 | (20.0) | 1 | (7.7) | ||

| MDD | 2 | (13.3) | 0 | (0) | ||

| CY-BOCS, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Total | 19.7 | (3.5) | 0.1 | (0.3) | t = 19.9 | <0.001 |

| Obsessions | 9.4 | (2.2) | 0.1 | (0.3) | t = 14.9 | <0.001 |

| Compulsions | 10.3 | (1.7) | 0.0 | (0.0) | t = 22.1 | <0.001 |

| OCD symptom dimensionse | ||||||

| Contamination/cleaning | 3.6 | (2.8) | ||||

| Ordering/repeating | 2.1 | (1.5) | ||||

| Hoarding | 1.7 | (1.7) | ||||

| Forbidden thoughts | 1.4 | (1.8) | ||||

| COIS-R, parent, mean (SD) | 32.9 | (23.0) | 0.1 | (0.3) | t = 5.2 | <0.001 |

| COIS-R, child, mean (SD) | 18.8 | (9.8) | 0.7 | (2.2) | t = 6.5 | <0.001 |

| YGTSS, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Total | 1.4 | (3.8) | 0.0 | (0.0) | t = 1.3 | 0.20 |

| Motor | 1.3 | (3.7) | 0.0 | (0.0) | t = 1.3 | 0.21 |

| Vocal | 0.1 | (0.3) | 0.0 | (0.0) | t = 1.0 | 0.33 |

| Volume, (mm) | ||||||

| Left caudate | 4361,9 | (551.4) | 4347.9 | (662.5) | 0.95 | |

| Right caudate | 4515.3 | (511.8) | 4409.5 | (786.7) | 0.67 | |

| Left putamen | 6540.1 | (559.5) | 6717,5 | (858.5) | 0.52 | |

| Right putamen | 6408.3 | (510.5) | 6368.9 | (830.6) | 0.88 | |

| Left nucleus accumbens | 727.9 | (109.6) | 724.5 | (122.2) | 0.94 | |

| Right nucleus accumbens | 814.3 | (149.5) | 792.2 | (111.3) | 0.67 | |

Note: ADHD = Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, COIS-R = Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale – Revised, CY-BOCS = Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, MDD = Major Depressive Disorder, OCD = Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, ODD = Oppositional Defiant Disorder, SES = socioeconomic status, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, WASI = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, YGTSS = Yale Global Tic Severity Scale

2 OCD subjects excluded from most analyses, 1 did not finish scan, 1 subject's scan was eliminated due to motion artifacts

Female Tanner stage based on pubic hair only

1 on clonazepam, 1 on methylphenidate, 1 on buspirone and dextroamphetamine/amphetamine, and 1 on propranolol and memantine

Generalized anxiety disorder was not assessed

CY-BOCS checklist was used to calculate scores on 4 factor-analyzed symptom dimensions (Bernstein et al., 2013)

3.2. Whole Brain Analyses

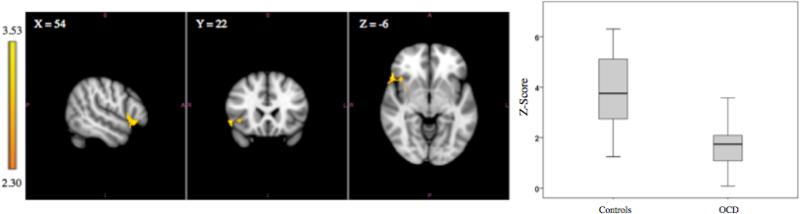

Adolescents with OCD compared with controls exhibited lower functional connectivity between the left putamen and a single right-sided cortical region including the OFC, inferior frontal gyrus, insula, and operculum (z-value = 3.53, p = 0.0066). The size of the cluster was 331 voxels. The critical cluster size as determined by the FSL software program was 322 voxels using p < 0.0107 as the cluster defining threshold. The MNI coordinates of the peak voxel were x = 54, y = 22, and z = −6 which is located in the area of the inferior frontal gyrus. See Figure 1 and Table 2. After correcting for multiple comparisons (using p <0.0083), no significant group differences were present using the right putamen, bilateral caudate, or bilateral nucleus accumbens seeds.

Figure 1.

Left images depict functional connectivity of the left putamen seed in which the OCD group has lower functional connectivity compared to the control group with the insula, inferior frontal gyrus, central opercular cortex, and orbitofrontal cortex. The coordinates represent the position of the voxel with the highest intensity in MNI standard space (z-score = 3.53). Right image is a boxplot comparing the range of functional connectivity z-scores between the left putamen and this cluster for the two groups. The means (bars within the boxes) and ranges (limit lines) represent z-scores in the cluster for the two groups.

Table 2.

Location, size, and peak z-values of the significant cluster in the group analyses

| Contrast | Seed Region | Brain Regions | # of Voxels | MNI Coordinates of Peak Voxel (x, y, z) | Peak z-value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls>OCD | Left Putamen | Right: Orbitofrontal Cortex, Inferior Frontal Gyrus, Insula, Central Opercular Cortex | 331 | 54, 22 -6 | 3.53 | 0.0066 |

3.3. Association of Connectivity with OCD Severity and Impairment

We extracted the mean z-scores representing left putamen connectivity within the area of group difference for each individual. In the OCD group, there were no significant correlations between this measure of functional connectivity and severity of OCD symptoms on CY-BOCS, between connectivity and dimensional scores on the CY-BOCS Checklist, and between connectivity and impairment due to OCD on COIS-R.

3.4. Volumetric Size of the Caudate, Putamen, and Nucleus Accumbens

There were no significant differences between the OCD and control groups on the volumes of the bilateral caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens, as shown in Table 1.

4. DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated reduced connectivity between the left putamen and a single right-sided cortical region including the OFC, inferior frontal gyrus, insula, and operculum in adolescents with OCD. Reduced connectivity between the putamen and the OFC and the inferior frontal gyrus supports our hypothesis that abnormalities in functional connectivity in the CSTC are associated with pediatric OCD. In addition, there was lower connectivity between the putamen and insula/operculum, which implicates key regions in the salience network as important in pediatric OCD.

The caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens, the seed regions, were once believed to be primarily motor structures, but research on non-human primates, human lesion studies, and human neuroimaging studies demonstrate that the basal ganglia are involved with a broader range of functions including motor, cognitive, motivational, and emotional processes (reviewed by Di Martino et al., 2008). The architecture of functional connectivity networks associated with the striatum in healthy adults has been documented. Di Martino and colleagues (2008) demonstrated that humans show evidence for an organization consisting of parallel and integrated loops as has been shown in animals. For example, the inferior striatum seeds revealed functional connectivity with the medial portions of the OFC, whereas more superior seeds were connected with both medial and lateral OFC.

Four previous studies used R-fMRI to evaluate functional connectivity in youths with OCD (Fitzgerald et al., 2010; Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Gruner et al., 2014; Weber et al., 2014). Fitzgerald and colleagues (2011) reported lower connectivity in the CSTC circuits in children ages 8-12 with OCD (but not in adolescents and adults with OCD). Specifically, they found reduced connectivity in the rostral ACC-dorsal striatum and dorsal ACC-medial dorsal thalamus connections. Gruner and colleagues (2014) and Weber and colleagues (2014) employed ICA, a different approach to analysis of whole brain functional connectivity data, in pediatric OCD. ICA is a data-driven approach that evaluates interactions among multiple brain regions and does not rely on selection of seed regions. Gruner et al. (2014) used an ICA approach to compare resting-state fluctuations between 23 youths with OCD (half on SSRIs) and 23 matched controls. Independent component expression scores were significantly higher in patients compared with controls in a middle frontal dorsal anterior cingulate network and in an anterior/posterior cingulate network and lower in a visual network. Weber and colleagues (2014) assessed functional connectivity in 11 medication-naïve children and adolescents with OCD and 9 healthy controls. The researchers found decreased connectivity in the right cingulate network (Brodmann areas 8 and 40). Brodmann area 8 relates to uncertainty (Volz et al., 2005), which from a clinical perspective is consistent with the obsessions and compulsions in OCD.

Thus, our findings and two of the previous four R-fMRI studies in youths with OCD provide evidence for reduced connectivity between specific regions in CSTC circuits (Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Weber et al., 2014). The current findings are in agreement with the Harrison et al. (2009) study in adults with OCD that demonstrated decreased functional connectivity between the dorsal putamen and inferior lateral prefrontal cortex. Our finding is consistent with a recent theory proposed by Gruner and colleagues (2015) that OCD is characterized by abnormal functional connectivity of the anterior inferior lateral prefrontal cortex, which overlaps with the cortical cluster identified in the current study. The anterior inferior lateral prefrontal cortex is involved with the regulation of habitual behavior and disruption of circuitry in this region could lead to inflexible reliance on habits as seen in individuals with OCD. Using a data-driven global brain connectivity approach, Anticevic and colleagues (2014) analyzed R-fMRI data of 27 adult OCD patients (half were medication-free) and 66 matched healthy control participants. Participants with OCD compared with controls showed reduced connectivity in the left lateral prefrontal cortex, both globally and specifically with the dorsal putamen.

Our results do not replicate an earlier finding of greater connectivity between the ventral striatum and OFC in adults with OCD compared with controls (Harrison et al., 2009; Sakai et al., 2011). Harrison et al. (2009) and Sakai et al. (2011) used similar methodologies to the current study (i.e., whole brain approach with seeds in the striatum). However, the seeds used in our study are larger than those used by Harrison et al. (2009) and Sakai et al. (2011), covering the entire caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens. Furthermore, our study was conducted in teenagers with OCD while the other two studies were conducted in adults. Age or pubertal stage may have an effect on connectivity findings in OCD. Fitzgerald and colleagues (2011) showed significant differences in connectivity between children with OCD and older participants. Children ages 8 to 12 compared with adolescents and adults showed lower connectivity between the dorsal striatum and rostral ACC and between the medial dorsal thalamus and dorsal ACC. To understand if there are developmental changes in OCD connectivity over time (e.g., lower functional connectivity in youth with OCD compared with higher connectivity in adults with OCD), there is a need for longitudinal studies to track brain connectivity from childhood into adulthood.

The current study also found lower connectivity between the putamen and the right insula/operculum. The operculum is the “lid” covering the insula. The insula and operculum are the cortical areas involved in interoception (Craig, 2002; Critchley et al., 2004) and have been identified as key areas (along with the OFC, dorsal ACC, extended amygdala, ventral pallidostriatum, thalamus, and temporal pole) in the “salience network”. The salience network signals the presence of events that are personally salient to the individual, assists with conflict monitoring, and facilitates behavioral responses to these stimuli (Seeley et al., 2007; Menon and Uddin, 2010). This network has been proposed to represent a system with the capacity to integrate the constant bombardment of many internal and external stimuli, and to allow individuals to assess the personal relevance of these stimuli to inform their actions (Seeley et al., 2007). These regions have previously been identified in OCD pathophysiology. A study in youths with OCD reported decreased connectivity between the dorsal ACC and right anterior operculum (Fitzgerald et al., 2010). Support for involvement of the insula in OCD comes from an fMRI study that compared 16 adults with OCD and 17 healthy controls using a symptom provocation paradigm (e.g., provocation of washing-related anxiety) (Mataix-Cols et al., 2004). There was a significant positive correlation between neural activation in the anterior insula and scores on the washing subscale of the Padua Inventory Revised. In another fMRI study, OCD participants with primarily washing compulsions compared with healthy controls showed greater activation of the right insula when viewing disgust-inducing pictures (Shapira et al., 2003).

Abnormal connectivity between putamen and insula/operculum has been described previously in a different population, but one that also has repetitive behavior as a key feature. A recent seed-based, whole brain R-fMRI study of 12 adolescents with internet gaming disorder compared with 11 matched healthy controls revealed lower functional connectivity between the putamen and the posterior insula/parietal operculum in participants with internet addiction (Hong et al., 2014). The authors note that previous imaging studies had implicated corticostriatal connectivity changes in addiction disorders and their study identified another important brain connection (i.e., putamen-insula/operculum) related to internet addiction (Hong et al., 2014). The overlapping findings with those of the present study suggest that abnormal connectivity in this circuit may represent an important mechanism underlying repetitive behaviors across psychiatric disorders.

Some studies support reduced connectivity in the CSTC in adults with OCD (Jang et al., 2010; Posner et al., 2014), other studies show increased connectivity in the CSTC (Sakai et al., 2011; Beucke et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2013), and some studies show both decreased and increased connectivity in the CSTC (Harrison et al., 2009; Fitzgerald et al., 2011). Several important variables may explain differences between study results: location of seeds, whether participants are taking SSRIs, age of participants, and comorbid conditions.

To properly compare seed-based functional connectivity studies, it is important to understand the similarities and differences between the seeds used in each study. The seeds used in our study were larger and more anatomically specific than those used in previous studies and included the entire caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens as determined for each subject individually by Freesurfer. In comparison, the seeds used in the Harrison et al. (2009), Sakai et al. (2011), and Fitzgerald et al. (2011) investigations were much smaller spherical seeds defined as coordinates on the MNI template. Harrison et al. (2009) and Sakai et al. (2011) used the same three bilateral caudate seeds. Their dorsal caudate and ventral caudate superior seeds map onto the boundary between the nucleus accumbens and caudate seeds for most subjects, falling mostly onto the nucleus accumbens in some subjects and onto the caudate in others. In addition, the Harrison et al. (2009) investigation used three bilateral spherical seeds from parts of the putamen. For all subjects, the three putamen seeds used by Harrison et al. (2009) mapped onto the Freesurfer putamen seed used in this study. See Supplemental Figure 4 for location of the Harrison et al. (2009) seeds with respect to our seeds. The study of Fitzgerald and colleagues (2011) used the dorsal caudate and ventral caudate/nucleus accumbens seeds used by Harrison et al. (2009) and Sakai et al. (2011).

Antidepressants can alter functional connectivity in depressed patients (Heller et al., 2013; Posner et al., 2013). A study of the effects of escitalopram, an SSRI, on brain connectivity in 22 healthy subjects revealed interesting findings (Schaefer et al., 2014). Using a network-centrality analysis, after only one dose of escitalopram there were decreases in functional connectivity in most cortical and subcortical areas. In addition, localized increases in connectivity were found in the thalamus and the cerebellum. The study suggested that serotonin modulates intrinsic brain activity. Thus, connectivity findings in medicated subjects likely reflect effects of the pharmacological treatment, as well as the underlying disease. Currently it is not known whether psychotropic medications affect connectivity differently in youths versus adults.

In addition, contrasting results in the literature may be explained by other methodological differences between studies (e.g., duration of scans, inclusion versus exclusion of OCD subtypes such as hoarders). These factors are likely less critical in explaining contrasting findings than the earlier mentioned factors (i.e., medication effects, locations of seeds, pediatric versus adult participants comorbidity).

This is one of the few studies of R-fMRI in pediatric OCD. Other strengths of this investigation include 24 minutes of R-fMRI data. The average acquisition time for a single resting-state scan is 5 to 10 minutes (Hutchison et al., 2013). In addition, scans were collected on the HCP scanner that provides imaging data with higher spatial and temporal resolution. Further, we employed rigorous methods to minimize ROI registration errors and to correct for confounds due to motion.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size. In addition, most of the OCD adolescents were medicated. Therefore, it is unclear to what extent our results reflect effects of disease, treatment, or both. For example, it may be that prior to pharmacological treatment, group differences were greater than we detected (i.e., even lower connectivity in the OCD group compared with controls) and were mitigated by treatment. Another confound may be comorbidity in the OCD patients. Forty percent of the OCD subjects in our study had ADHD. It is possible that the connectivity findings reflect comorbid condition (e.g., ADHD, rather than being due entirely to OCD). However, it is very difficult to recruit “pure” OCD patients for research. A review of clinical studies of pediatric OCD showed rates of 63-97% for any comorbid psychiatric disorder (Geller, 2010). Thus, in studies that exclude participants with comorbid disorders, the data are not generalizable to the population of youth with OCD in clinic samples.

Another shortcoming is our use of a liberal threshold (p < 0.0107) (Woo et al., 2014) when running FSL FEAT analyses for the seed-based whole brain connectivity. We used the default z threshold of 2.3 (which corresponds to p < 0.0107) and adjusted the alpha to p < 0.0083 to correct for the multiple tests (i.e., six separate analyses). Our choice of a liberal threshold was due to the small sample size of our pilot study and because p < 0.0107 is the default primary threshold in FSL. We are currently collecting similar data in a larger sample of unmedicated OCD youths and healthy controls that will be analyzed using a more stringent threshold (i.e., p < 0.001) to determine if our current findings are replicated. In addition, we did not collect data about levels of arousal, obsessions, anxiety, or attention before and after the MRI and therefore cannot determine if group differences on these variables may account for different connectivity patterns between groups. It is possible that some subjects in each group fell asleep during the first or second 12 minutes of scanning which may have impacted connectivity findings. In our current neuroimaging studies in youths with OCD, we are collecting these data (i.e., levels of arousal, obsessions, and anxiety) immediately before and after scanning and will correlate them with connectivity scores to evaluate relations between cognitive state and resting data. Finally, the mean IQ of the OCD group was 115, which is greater than one SD above the mean. Therefore, our data may not be generalizable to all teenagers with OCD.

Our study helps to delineate the neurobiological mechanisms of pediatric OCD, namely reduced functional connectivity in the putamen-OFC/inferior frontal gyrus connections within the CSTC and reduced connectivity in putamen-insula/operculum connections. Whether such functional connectivity differences are the cause or the consequence of the psychiatric disease state is yet to be determined (Hutchison et al., 2013). The resting-state findings from neuroimaging studies have the potential for identifying objective resting-state connectivity markers to predict and measure response to treatment and for guiding the development of new pharmacological treatments for OCD. The next steps will include characterizing the specific neural changes that predict response to established pharmacological treatments and determining the specific neurobiological differences in patients who do not respond to standard treatments. As stated by Hutchison and colleagues, “Quantification of disrupted dynamics (in neural networks) in clinical populations may lead to a better understanding of the disorder, more targeted drug treatment, and eventually diagnostic or prognostic indicators” (Hutchison et al., 2013, p. 372). Our preliminary findings suggest reduced connectivity in adolescents with OCD between the left putamen and a single right-sided cluster including the inferior frontal gyrus, insula, operculum, and a small region of the OFC. Additional R-fMRI investigations of these regions will be necessary to support the results of this pilot investigation.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Correlations between left putamen connectivity z-scores and clinical scales in OCD group (n = 15)

| Pearson Correlation | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Child COIS-R total | −.238 | .433 |

| Parent COIS-R total | .176 | .584 |

| CY-BOCS | ||

| Total | .046 | .872 |

| Hoarding | .126 | .655 |

| Ordering/repeating | −.224 | .422 |

| Forbidden thoughts | −.397 | .143 |

| Contamination | −.286 | .301 |

COIS-R = Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale – Revised, CY-BOCS = Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, OCD = Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

HIGHLIGHTS.

Adolescents with OCD show abnormal striatal resting-state functional connectivity.

Teens with OCD have lower connectivity between putamen and a cluster of cortical areas.

Cortical areas are orbitofrontal cortex, inferior frontal gyrus, insula, & operculum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors extend special thanks to the adolescents and their parents who participated in the study. This study was funded by the Academic Health Center Seed Grant and grants from the National Institutes of Health including R21MH101395 (Bernstein), the Human Connectome Project (1U54MH091657), 1P30NS076408, and P41EB015894. The work was carried out in part using computing resources at the University of Minnesota Supercomputing Institute. The funding sponsors had no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing the manuscript; or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors Bernstein, Mueller, and Cullen designed the study. Authors Mueller, Schreiner, Campbell, Regan, Nelson, and Houri collected the data. Authors Mueller, Schreiner, Lee, and Cullen conducted the analyses of the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and discussed content of the paper. Author Bernstein wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to the final manuscript.

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1986;9:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anticevic A, Hu S, Zhang S, Savic A, Billingslea E, Wasylink S, Repovs G, Cole MW, Bednarski S, Krystal JH, Bloch MH, Li CS, Pittenger C. Global resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging analysis identifies frontal cortex, striatal, and cerebellar dysconnectivity in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2014;75:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein GA, Victor AM, Nelson PM, Lee SS. Pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: symptom patterns and exploratory factor analysis. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2013;2:299–305. [Google Scholar]

- Beucke JC, Sepulcre J, Talukdar T, Linnman C, Zschenderlein K, Endrass T, Kaufmann C, Kathmann N. Abnormally high degree connectivity of the orbitofrontal cortex in obsessive-compulsive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:619–629. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:655–666. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Ohman A, Dolan RJ. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:189–195. doi: 10.1038/nn1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KR, Vizueta N, Thomas KM, Han GJ, Lim KO, Camchong J, Mueller BA, Bell CH, Heller MD, Schulz SC. Amygdala functional connectivity in young women with borderline personality disorder. Brain Connect. 2011;1:61–71. doi: 10.1089/brain.2010.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KR, Westlund MK, Klimes-Dougan B, Mueller BA, Houri A, Eberly LE, Lim KO. Abnormal amygdala resting-state functional connectivity in adolescent depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1138–1147. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino A, Scheres A, Margulies DS, Kelly AM, Uddin LQ, Shehzad Z, Biswal B, Walters JR, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Functional connectivity of human striatum: a resting state FMRI study. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18:2735–2747. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg DA, Moeller S, Smith SM, Auerbach E, Ramanna S, Glasser MF, Miller KL, Ugurbil K, Yacoub E. Multiplexed echo planar imaging for sub-second whole brain FMRI and fast diffusion imaging. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald KD, Stern ER, Angstadt M, Nicholson-Muth KC, Maynor MR, Welsh RC, Hanna GL, Taylor SF. Altered function and connectivity of the medial frontal cortex in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald KD, Welsh RC, Stern ER, Angstadt M, Hanna GL, Abelson JL, Taylor SF. Developmental alterations of frontal-striatal-thalamic connectivity in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:938–948. e933. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8:700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. In: Dulcan MK, editor. Textbook of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; Washington DC: 2010. pp. 349–363. [Google Scholar]

- Greve DN, Fischl B. Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. Neuroimage. 2009;48:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruner P, Anticevic A, Lee D, Pittenger C. Arbitration between Action Strategies in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Neuroscientist. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1073858414568317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruner P, Vo A, Argyelan M, Ikuta T, Degnan AJ, John M, Peters BD, Malhotra AK, Ulug AM, Szeszko PR. Independent component analysis of resting state activity in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Human Brain Mapping. 2014;35:5306–5315. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison BJ, Soriano-Mas C, Pujol J, Ortiz H, Lopez-Sola M, Hernandez-Ribas R, Deus J, Alonso P, Yucel M, Pantelis C, Menchon JM, Cardoner N. Altered corticostriatal functional connectivity in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:1189–1200. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller AS, Johnstone T, Light SN, Peterson MJ, Kolden GG, Kalin NH, Davidson RJ. Relationships between changes in sustained fronto-striatal connectivity and positive affect in major depression resulting from antidepressant treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170:197–206. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. Yale University Department of Sociology; New Haven, CT.: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hong SB, Harrison BJ, Dandash O, Choi EJ, Kim SC, Kim HH, Shim DH, Kim CD, Kim JW, Yi SH. A selective involvement of putamen functional connectivity in youth with internet gaming disorder. Brain Research. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison RM, Womelsdorf T, Allen EA, Bandettini PA, Calhoun VD, Corbetta M, Della Penna S, Duyn JH, Glover GH, Gonzalez-Castillo J, Handwerker DA, Keilholz S, Kiviniemi V, Leopold DA, de Pasquale F, Sporns O, Walter M, Chang C. Dynamic functional connectivity: Promise, issues, and interpretations. Neuroimage. 2013;80:360–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyser C, Veltman DJ, de Haan E, Boer F. Paediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder, a neurodevelopmental disorder? Evidence from neuroimaging. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;33:818–830. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang JH, Kim JH, Jung WH, Choi JS, Jung MH, Lee JM, Choi CH, Kang DH, Kwon JS. Functional connectivity in fronto-subcortical circuitry during the resting state in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuroscience Letters. 2010;474:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra SK, Swedo SE. Children with obsessive-compulsive disorder: Are they just “little adults”? Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119:737–746. doi: 10.1172/JCI37563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang DH, Jang JH, Han JY, Kim JH, Jung WH, Choi JS, Choi CH, Kwon JS. Neural correlates of altered response inhibition and dysfunctional connectivity at rest in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2013;40:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RE, Jr., Alexopoulos GS, Wang Z, Gunning FM, Murphy CF, Morimoto SS, Kanellopoulos D, Jia Z, Lim KO, Hoptman MJ. Visual inspection of independent components: Defining a procedure for artifact removal from fMRI data. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2010;189:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen HU. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169–184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, Ort SI, Swartz KL, Stevenson J, Cohen DJ. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: Initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28:566–573. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Li S, Dong Z, Luo J, Han H, Xiong H, Guo Z, Li Z. Altered resting state functional connectivity patterns of the anterior prefrontal cortex in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuroreport. 2012;23:681–686. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328355a5fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia TV, Cooney RE, Peterson BS. The neural bases of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adults. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:1251–1283. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Cols D, Wooderson S, Lawrence N, Brammer MJ, Speckens A, Phillips ML. Distinct neural correlates of washing, checking, and hoarding symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:564–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazziotta JC, Toga AW, Evans A, Fox P, Lancaster J. A probabilistic atlas of the human brain: theory and rationale for its development. The International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM). Neuroimage. 1995;2:89–101. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, Uddin LQ. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214:655–667. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies L, Chamberlain SR, Laird AR, Thelen SM, Sahakian BJ, Bullmore ET. Integrating evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychological studies of obsessive-compulsive disorder: The orbitofronto-striatal model revisited. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32:525–549. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, Rauch SL. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: beyond segregated cortico-striatal pathways. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller S, Yacoub E, Olman CA, Auerbach E, Strupp J, Harel N, Ugurbil K. Multiband multislice GE-EPI at 7 tesla, with 16-fold acceleration using partial parallel imaging with application to high spatial and temporal whole-brain fMRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2010;63:1144–1153. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Peris TS, Bergman RL, Chang S, Jaffer M. Functional impairment in childhood OCD: Development and psychometrics properties of the Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale-Revised (COIS-R). Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:645–653. doi: 10.1080/15374410701662790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner J, Hellerstein DJ, Gat I, Mechling A, Klahr K, Wang Z, McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Peterson BS. Antidepressants normalize the default mode network in patients with dysthymia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:373–382. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner J, Marsh R, Maia TV, Peterson BS, Gruber A, Simpson HB. Reduced functional connectivity within the limbic cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical loop in unmedicated adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Human Brain Mapping. 2014;35:2852–2860. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage. 2012;59:2142–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Kessler RC. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010;15:53–63. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y, Narumoto J, Nishida S, Nakamae T, Yamada K, Nishimura T, Fukui K. Corticostriatal functional connectivity in non-medicated patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. European Psychiatry. 2011;26:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, Cicchetti D, Leckman JF. Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: Reliability and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:844–852. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A, Burmann I, Regenthal R, Arelin K, Barth C, Pampel A, Villringer A, Margulies DS, Sacher J. Serotonergic modulation of intrinsic functional connectivity. Current Biology. 2014;24:2314–2318. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, Reiss AL, Greicius MD. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira NA, Liu Y, He AG, Bradley MM, Lessig MC, James GA, Stein DJ, Lang PJ, Goodman WK. Brain activation by disgust-inducing pictures in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:751–756. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Child and Parent Versions. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX.: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Pina AA. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Murphy TK, Adkins JW, Lewin AB, Geffken GR, Johns NB, Jann KE, Goodman WK. The Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale: Psychometric properties of child- and parent-report formats. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20:1055–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz KG, Schubotz RI, von Cramon DY. Variants of uncertainty in decision-making and their neural correlates. Brain Research Bulletin. 2005;67:403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber AM, Soreni N, Noseworthy MD. A preliminary study of functional connectivity of medication naive children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2014;53:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) Harcourt Assessment; San Antonio, TX.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Woo CW, Krishnan A, Wager TD. Cluster-extent based thresholding in fMRI analyses: pitfalls and recommendations. Neuroimage. 2014;91:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.12.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, Barrios V. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:335–342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Moeller S, Auerbach EJ, Strupp J, Smith SM, Feinberg DA, Yacoub E, Ugurbil K. Evaluation of slice accelerations using multiband echo planar imaging at 3T. Neuroimage. 2013;83:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.