Abstract

Health information technology (IT) has opened exciting avenues for capturing, delivering and sharing data, and offers the potential to develop cost-effective, patient-focused applications. In recent years, there has been a proliferation of health IT applications such as outpatient portals. Rigorous evaluation is fundamental to ensure effectiveness and sustainability, as resistance to more widespread adoption of outpatient portals may be due to lack of user friendliness. Health IT applications that integrate with the existing electronic health record and present information in a condensed, user-friendly format could improve coordination of care and communication. Importantly, these applications should be developed systematically with appropriate methodological design and testing to ensure usefulness, adoption, and sustainability. Based on our prior work that identified numerous information needs and challenges of HCT, we developed an experimental prototype of a health IT tool, the BMT Roadmap. Our goal was to develop a tool that could be used in the real-world, daily practice of HCT patients and caregivers (users) in the inpatient setting. In the current study, we examined the views, needs, and wants of patients and caregivers in the design and development process of the BMT Roadmap through two user-centered Design Groups, conducted in March 2015 and April 2015, respectively: Design Group I utilized a low-fidelity paper-based prototype and Design Group II utilized a high-fidelity prototype presented to users as a web-app on Apple® iPads. There were 11 caregivers (median age 44, range 34–69 years) and 8 patients (median age 18 years, range 11–24 years) in the study population. The qualitative analyses revealed a wide range of responses helpful in guiding the iterative development of the system. Three important themes emerged from the Design Groups: 1) perception of core features as beneficial (views), 2) alerting the design team to potential issues with the user interface (needs); and 3) providing a deeper understanding of the user experience in terms of wider psychosocial requirements (wants). From the patient and caregiver perspectives, the BMT Roadmap system was considered useful. The findings from the Design Groups resulted in changes that led to an improved, functional BMT Roadmap product. This unique research process and the findings reported herein included data generated from patients, caregivers, providers, and researchers as partners. Collectively, the data informed the design and development of the tool, which will be tested as an intervention in the pediatric HCT population at our center in the fall of 2015 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02409121).

Keywords: Health IT, Caregiver, Design Group, Engagement, User-Centered Design, Pediatric, Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Engaging patients in their healthcare has been shown to improve outcomes and is rapidly being embraced as the optimal approach for delivering care.1–3 This is especially needed for patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) due to the length, intensity, and potentially life-threatening complications from the therapy.4 Patients and families undergoing HCT have described a need for more active involvement in their care5,6 and a wide variety of information needs.7

Engagement has the potential to reduce ‘information asymmetry,’ wherein an imbalance exists in the information available to healthcare teams compared with patients.8,9 Providing patients with access to their own healthcare data can reduce information asymmetry, promote transparency, and increase engagement.10 This type of information-sharing has already proven to be effective and well-embraced with initiatives, such as the Open Notes11 project and in the widespread deployment of outpatient portals,12–14 the latter of which has been defined as applications managed by healthcare institutions that provide patients with access to their electronic health record (EHR) data and may also “offer functions and services that are targeted towards enhancing medical treatment.”15

Interestingly, engagement in the inpatient setting, including the use of inpatient portals, is lagging compared with what has been done in the outpatient setting.16,17 Yet, the need for real-time information to reduce information asymmetry could not be greater, especially since clinical decisions are made at all hours of the day.2 Hospitals and healthcare systems are beginning to embrace this ideal, and some inpatient portals are beginning to be deployed.18,19 Despite the importance of involving patients in their healthcare,20 it is unclear how many of the portals currently being developed or deployed have involved patients in their design. This is important, because resistance toward more widespread adoption of outpatient portals may be due to the lack of user friendliness.14 Indeed, participatory design processes can reveal problems that might not otherwise be uncovered,21 including those related to ‘terminology,’ ‘portal navigation,’ ‘task completion,’ ‘satisfaction,’ and ‘ease-of-use.’22 Importantly, a one-size-fits all approach for portals is antithetical to the concept of ‘tailoring,’23 one form of which involves changing the information provided depending on the information needs of individual patients or similar patient populations. 24,25

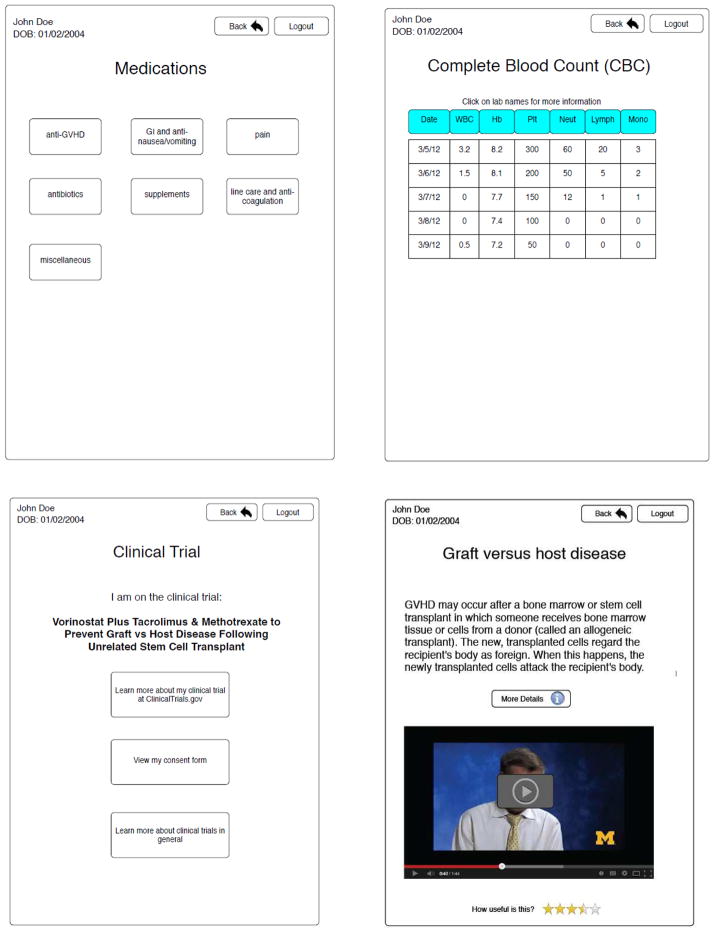

Recently, we examined the information needs and challenges of pediatric HCT patients and caregivers and identified numerous issues in which an inpatient portal could help alleviate their anxiety and satisfy their information needs.26–28 Based on formative evaluations, basic requirement studies, and insights gained from semi-structured qualitative interviews with patients, caregivers, nurses, pharmacists, nutritionists, advanced practice nurses, and physicians,26–28 we developed an experimental paper-based prototype of a health IT tool, the BMT Roadmap (Figure 1).28 Our goal was to develop a tool that could be used in the real-world, daily practice of HCT patients and caregivers (users) in the inpatient setting. The BMT Roadmap is a portable, tablet-based platform (Apple® iPad) for patients and caregivers to visualize real-time: 1) laboratory results (Labs) and medications (Meds); 2) patient-specific clinical trial and signed informed consent data; 3) health care provider profiles; and 4) discharge criteria checklist. By providing patient-specific health information updated in real-time, the BMT Roadmap system was intended to build knowledge, self-concept, and activation.

Figure 1.

Phase I – Example of the experimental paper-based prototype

Within this framework, it was important to understand the usability of the BMT Roadmap from the perspective of users. The purpose of the current study was to examine the views, needs, and wants of patients and caregivers in the design and development process of the BMT Roadmap through user-centered Design Groups.

METHODS

Study Design

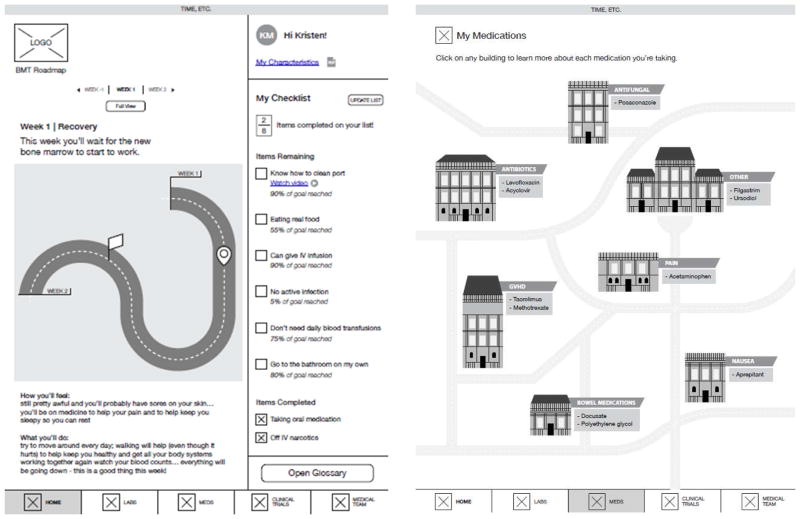

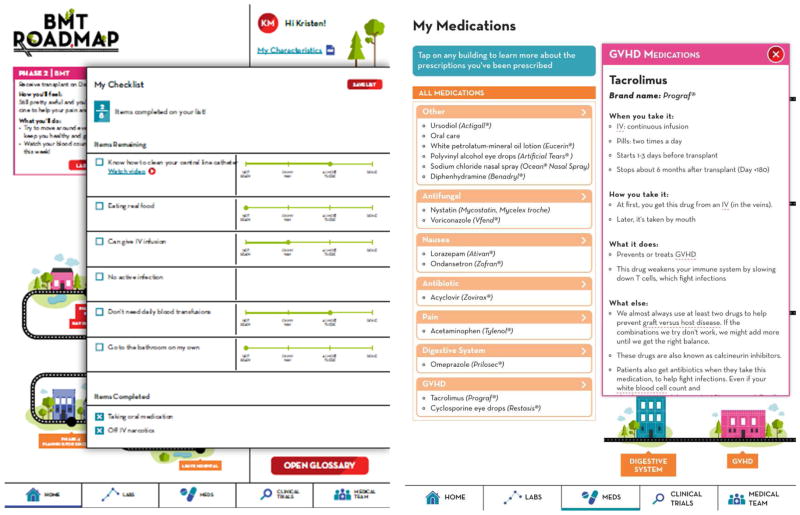

This work is part of a three-phase project (Supplemental Figure 1). In Phase 1, an experimental paper-based prototype of a health IT tool, the BMT Roadmap, was developed in 2014.28 In Phase 2 (the present study) two Design Groups were conducted with patients and caregivers in March and April 2015 using low fidelity and high fidelity prototypes, respectively (Figures 2 and 3). In Phase 3, a pilot, exploratory study, “Personalized engagement tool for pediatric BMT patients and caregivers,” funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02409121, will examine the use of a patient- and caregiver-controlled, web-based inpatient portal, the BMT Roadmap, in the inpatient HCT setting. Phase 2 focuses on the design and development of the BMT Roadmap from the user perspective prior to its implementation in Phase 3. Ethical approval was obtained by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB number HUM00100126). Details regarding “Definition of Design Group” and “Background on the Experimental Prototype of the BMT Roadmap” can be found in Supplemental Methods.

Figure 2.

Phase 2 - Examples from low-fidelity prototype from Design Group 1, on paper

Figure 3.

Phase 2 - Examples from high-fidelity prototype from Design Group II, on Apple® iPad web app

Study Site (Phase 2)

The Design Groups were located in a large conference room on the 7th Floor of the University of Michigan Mott Children’s Hospital, adjacent to the Pediatric HCT Unit. The Pediatric HCT Unit included the Inpatient Unit, Outpatient Clinic, and Infusion center spaces, which were all located on the 7th floor, facilitating recruitment and study participation. Transplant physicians and nurse coordinators recruited study participants from these sites directly. Each participant was provided with a $50 gift card at the completion of the study.

Study Sample (Phase 2)

The eligibility criteria avoided restrictive criteria that would adversely affect accrual and negatively impact the ability to generalize preliminary findings from this initial study. Inclusion criteria were: 1) caregiver (age 18 years or older) of a patient who underwent autologous or allogeneic HCT in the Pediatric HCT Unit; 2) patient (age 10 years or older) who underwent autologous or allogeneic HCT; 3) ability to speak and read proficiently in English; 4) willing and able to provide informed consent; and 5) willing to have the session audio-recorded.

Design Groups (Phase 2)

Before initiating the study, a moderator guide was developed by the study investigators, who included experts in HCT (SWC), health informatics (DAH and MM), human-computer interaction (EK), and health communications (HD, RF, KM, and DOR). The moderators used the guide to cover the usefulness and heuristic usability of the prototypes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Design Group Moderator Guide

| Design Group I – Low-Fidelity Prototype | Design Group II – High-Fidelity Prototype |

|---|---|

|

| |

After introduction to general features:

After reviewing individual modules:

|

Tasks were completed in small groups, with a researcher tracking:

Task prompts:

Following time interacting with each module (Laboratories, Medications, Clinical Trials, Roadmap, Checklist for Discharge, Medical Team):

|

Design Group I was conducted in March 2015 and Design Group II was conducted in April 2015. Upon arrival to the study site, participants signed the informed consent (assenting minors age ≥ 10 years also signed the consent form) and completed a brief questionnaire that collected information on socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. No patient identifiers were retained. Each group lasted approximately 2 hours and was audio-recorded with consent by the participants.

A moderator (EK) trained in human-computer interaction design techniques, health informatics (MM), and assistants (HD, RF, KM, and DOR) with backgrounds in health communication research moderated both of the Design Groups. None were affiliated with the Pediatric HCT Program; this exclusion of HCT Program members was intentional to ensure that participants felt comfortable to discuss concerns freely with the Design Group team.

Design Group I utilized a low-fidelity prototype, representing the modules as wireframes printed out on paper (Figure 2). Feedback obtained from the first Design Group was used to improve upon the prototype and develop a more detailed, high-fidelity prototype for further discussion. Design Group II utilized this high-fidelity prototype, presented to users as a web-app on Apple® iPads. Some portions of this prototype functioned fully (e.g., navigating between screens), while others (e.g., viewing lab results) were represented as static digital images of the interface (Figure 3).

Data Analysis (Phase 2)

The Design Group recordings were professionally transcribed verbatim (Babbletype, Philadelphia, PA). Two members of the study team (MM and EK) analyzed the data using an open coding method in which each researcher independently identified significant concepts. The coded transcripts were then discussed among all of the authors. Analytical memos were also circulated and discussed among the study team as insights emerged from the ongoing data collection. Findings from Design Group I were incorporated both in prototype design changes and in the research scripting of Design Group II. The team drew upon previous ethnographic research27 to corroborate the findings of the two Design Group sessions.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

As shown in Table 2, a total of 11 caregivers and 8 patients participated in the Design Groups, representing five households in each Design Group. In two cases, the caregiver participated alone because their child was too young (ages 2 and 3 years old). In one case, a patient was joined by two caregivers. There was a gender mix in both caregiver and patient populations. Caregivers ranged between 34–69 years of age. Families included patients with varying times removed from HCT, between three months and five years post-transplant. Majority of them were from the Southeastern Michigan region. There were diverse socioeconomic responses, reflected by variable household health insurances (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample

| Number of households represented | 10 |

| Caregiver participants | 11 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 4 |

| Female | 7 |

| Age, median (range), years | 44 (34–69) |

| Patients (children of participants) | 10 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 5 |

| Female | 5 |

| Age, median (range), years | 15 (2–24) |

| School Status | |

| Full time | 3 |

| Part time | 1 |

| None | 6 |

| Diseases | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 5 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 1 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 1 |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 1 |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1 |

| Shwachman-Diamond syndrome | 1 |

| Participated in workshop | 8 |

| Age, median (range, years) | 18 (11–24)* |

| Time since first HSCT | 9 (3–60) |

| median (range), mo | |

| Hometown | |

| Ann Arbor, Washtenaw County | 1 |

| Other Southeastern Michigan | 5 |

| Other Michigan | 3 |

| No Response | 1 |

| Household Income | |

| $25,000 – 49,999 | 4 |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 1 |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 2 |

| $125,000 – $149,999 | 2 |

| $150,000 and more | 1 |

| Employment Status of Caregiver | |

| Full time | 4 |

| Self employed | 2 |

| Unemployed | 4 |

| Household Insurance | |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 2 |

| Private | 1 |

| Other† | 1 |

| Employer + Medicaid/Medicare | 1 |

| Private + Medicaid/Medicare | 2 |

| Employer + Other† | 3 |

Two patients were too young to participate in the Design Groups (ages 2 and 3 years old)

Three of “Other” included participant notation of Children’s Special Health, a program through the Michigan Department of Community Health

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative analysis revealed a wide range of user responses helpful in guiding the iterative development of the BMT Roadmap. We focus here on detailing three important themes from patients and caregivers that emerged from our Design Groups: 1) perception of core features as beneficial (views), 2) alerting the design team to potential issues with the user interface (needs); and 3) providing a deeper understanding of the user experience in terms of wider psychosocial requirements (wants).

I. Affirmation of Usefulness of Core Features

In general, there was constructive criticism of and brainstorming of improvements for the BMT Roadmap. Participants described satisfaction with its core features and design. Specifically, they recognized how certain functionality would have facilitated their information management during hospitalization. Participants described a perceived usefulness of several modules including the medication list, medical team, laboratory results and discharge checklist. They also referenced important functionality, including synchronous data updates and flexibility of checklist presentation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Perceived Usefulness of Core Function and Features

| Feature or function | Design Group Participant quote regarding usefulness |

|---|---|

| Presentation discharge criteria and phase descriptions from the time of admission. | “I was in a mode where I was like, tell me what I need to do because I’m tired of being in the hospital.” –Patient participant, Design Group I “The thing is that we didn’t know what she needed to do to get out until the very end.” –Caregiver participant, Design Group I |

| Ubiquitous access to self-educational information via the iPad. | We all stumbled in the dark when our child was up there. I mean, the nurses, the doctors would tell us things, and we would forget because we were overwhelmed. Just all of it at the push of a button would be great, because we do forget, and we are overwhelmed, and it is devastating. –Caregiver participant, Design Group I |

| Self-monitoring progress in individual discharge criterion via a 4-point scale (‘Not ready,’ ‘on my way,’ ‘almost there,’ ‘done’) that can be adjusted toward or away from completion at any time. | “I think that’s good. I like that there’s a progression so it’s not either off or on. I think that would be a little less depressing.” – Patient participant, Design Group II |

| Synchronous connection to EHR data, including real-time lab result releases. | “Right, or you forget, or you ask the nurse, “Can you tell me those counts again?” This would be nice to have on your own just to review it yourself.” –Caregiver participant, Design Group I “Me, I felt like I was nagging, to be like, “So, did you, did the labs come through yet? Are they back yet?”—Caregiver participant, Design Group II |

| Lab results visualized with ranges and thresholds. | “Because they’ll tell you the number, but they don’t tell you what it means. Or what’s normal, what’s too high or too low. So I like that it shows that aspect of it.” –Caregiver participant, Design Group I “My husband used to chart them out. He would do a graph on our computer.” –Caregiver participant, Design Group I |

| Medication listed by purpose and name, with details on reasons for prescription, form of intake, and side effects. | “I like how the details are put out like that and exactly what it’s for, what are the side effects. I like that.” –Caregiver participant, Design Group II |

| Medical team directory with name, title and headshot for all care team staff on the BMT unit. | “With rounds and everything, there would be people in there that I didn’t even know who they were, and they would know my whole medical history. Obviously they’re doctors and everything, but it would be nice to know who’s in my room and who’s talking about what and everything.” –Patient participant, Design Group I |

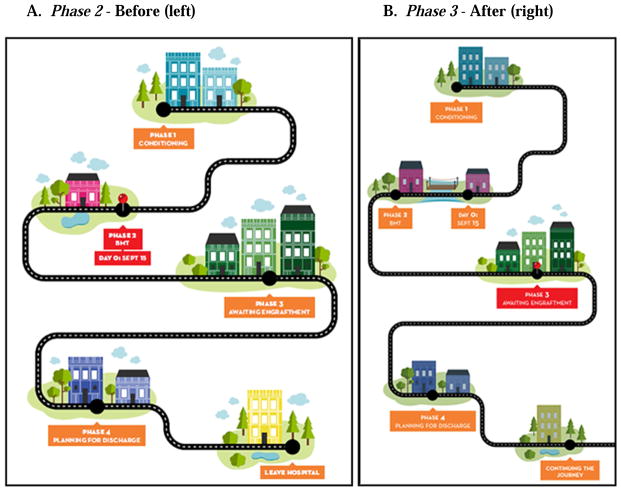

II. Designing the User Interface to Reflect Patient Experiences

The study team originally designed the user interface (UI) with a “roadmap” metaphor to reflect the purpose of the tool, a guided path for families through the hospitalization process that ended at discharge (Figure 4A). Many participants, particularly in Design Group I, however, indicated that this roadmap metaphor failed to capture the long-term impact of HCT. Instead, participants conceptualized the roadmap as extending far beyond their hospital discharge date. For the first 100 days post-transplant, most patients require controlled lifestyles and regular clinical attention to avoid infections or complications. Participants of the Design Group described the period after leaving the hospital as confusing and filled with challenges, and were often unprepared for the level of care that followed hospitalization. One participant noted that patients need to know they are “not out of the woods” following discharge, but will face future care challenges:

“My restrictions are lifted now, but I had no idea. I was totally blindsided. It would be nice to have that on here [user interface], to see that you’re not out of the woods yet until you hit day 100, that kind of thing.” – Patient participant, Design Group I

Figure 4.

Roadmap User Interface (UI) metaphor before (left) and after (right) Design Groups

Another participant indicated that patients and caregivers need support transitioning to life after discharge, and that the roadmap should not abruptly end at the hospital:

“I like it because it’s definitely a roadmap, but I think the after-discharge checklist should be on there because, like you said, it’s not over, and you have a long way to go, even longer than what you just did.” – Patient participant, Design Group II

In response to participant feedback, the study team visually extended the road to make an unending path (Figure 4B). Whereas the first design phase of the map from Design Group I displayed hospital discharge as the end of the patient path with a “Leave Hospital” icon (Figure 4A), the next design phase in Design Group II extended the road and substituted a “Continuing the Journey” icon (Figure 4B). This is an example of subtle design change that can impact the perceived usefulness of a patient-centered tool. We modified the design layout of the prototype to continue beyond discharge and the finalized version of the BMT Roadmap system will be tested for interventional use (Supplemental Figure 1: Phase 3) in the inpatient setting (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02409121).

III. Tailoring the User Experience to Support Patient Needs

The study team also found the Design Group research method helpful in eliciting the types of support patients found useful. Interacting with the prototype, participants described the types of information (content) they needed at each phase of the HCT process. We found that many of our participants thought it would be helpful to display content on the social and emotional dimensions of care as well as clinical data. As participants explained;

“I know I had a lot of anxiety [about the HCT process]. It would be good to have a section of how to deal with it, stuff you can fit in here, so that they know that they’re normal, and they’re okay.” –Patient Participant, Design Group I

“Especially the kids [need emotional support]. We have our families, but when you get a kid that’s sick with cancer, not even the parent knows how the child feels.” –Caregiver Participant, Design Group I

Our previous work informed our understanding of the intensive emotional needs and social stress patients and caregivers experience during HCT.27 Acting on user feedback about supporting these psychosocial needs, the prototype was modified after Design Group I from Supplemental Figures 2A to 2B, which now includes expectations for how a patient may feel emotionally and offers care resources to utilize.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we explored the views, needs, and wants of patients and caregivers in iterative phases toward the development of a health IT tool, the BMT Roadmap. An important finding of our work is that the Design Group approach allowed us to partner with individuals who have lived the HCT experience, probe their insights and perspectives, and make changes to the system that could be meaningful for future users. To our knowledge, this is the first report of utilizing user-centered techniques29 toward the development of a health IT tool in the HCT setting. In order to find a beneficial effect of the BMT Roadmap, the literature suggests that user acceptance is critical.30

Participants in the Design Groups articulated a wide range of suggestions to better support patients and caregivers going through HCT process. While it was not feasible to address all of these complex challenges in current design iterations, we have found participant (user) feedback helpful in framing future designs directions for the BMT Roadmap system. In line with another recent study,31 one of the desired functions of the BMT Roadmap was the capability of tracking daily goals. For example, a built-in feature to monitor and track patient-specific physical activity and nutrition data with target goals to achieve on a daily basis was one of the desired functions.32 While this design feature did not fit within the budget or resources of the current project, future iterations of the tool could consider this patient-centered feature. With regards to content, there was strong emphasis on psychosocial and emotional needs and participants pointed to areas where that information could be provided in the tool, consistent with our prior work.27,28 The study team plans to incorporate these patient-generated issues as probes for future studies on the HCT inpatient experience and explore ways in which future iterations of the BMT Roadmap system could support tailored personalized health information and social support.

Overall, the findings in this study suggest that many of the participants had positive perceptions about the BMT Roadmap system. The HCT population, in particular, could benefit from such innovative technologies to support their healthcare given the immense challenges that patients and caregivers face, both clinically and emotionally.26–28 HCT patients and caregivers experience significant distress at the time of discharge.33 Unfortunately, effective strategies that could better prepare and transition patients to self-manage their disease conditions from the inpatient to outpatient settings have been underdeveloped.34 Moreover, studies in self-efficacy and health management behaviors of parents have been associated with positive health outcomes for both parents and children.35,36 Therefore, it is strongly desired to promote efforts of self-efficacy and self-management.37

Meanwhile, the growing expectations to provide quality care by health care providers has led to increased attention to patient-centered care and outcomes.38 For example, an emerging health policy issue is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hospital Inpatient Value-Based Purchasing program, wherein reimbursements will be linked to patient satisfaction and quality.39,40 This intersection provides an opportunity to test novel interventions in patient-care related activities,41 particularly in patient populations with complex medical conditions and with high information needs, such as HCT patients who partner with caregivers and their healthcare providers in the co-management of their care.37 Health IT solutions, such as portals, offer the potential to overcome constraints in healthcare delivery limited by provider time, complicated health information, and financial pressures.2

As consumer-facing health IT tools reshape how health-related information is stored and communicated,9 accessibility and tailoring to user needs should be considered in the design and development phases.42 The literature suggests that patients desire to have access to a personally-controlled or patient-adapted version of the EHR.43,44 Accordingly, a user-friendly BMT Roadmap system has the potential to enhance the care and management given to patients and caregivers.

Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this study was the transdisciplinary approach that brought together expertise in HCT, health informatics, human-computer interaction, and health communications research. Careful and broad considerations of the design and development process were made through this unique team. For example, understanding and balancing the time and resources needed to employ Design Group vs. Design Workshop methodologies reflect the expertise of the team. Moreover, without consideration of patients’ needs and ability, the design, testing, and evaluation of patient engagement technology lack proof of usability or usefulness and may be alienating diverse populations.45 This failing can be addressed by applying principles of user-centered design in the development of consumer health technology.22,45,46 However, some aspects of participatory design practice may need to be adapted to operate under the constraints of the medical system and patients’ experiences,47 as was done in this study by conducting Design Groups.

While our work may be of interest to investigators conducting research in mobile health technology, we recognize the limitations of our findings. Our study examined the perspectives of children, adolescents, and young adults and caregivers in the design of a health IT system. Limitations of our study include: First, the Design Groups were conducted at a single institution (University of Michigan) and we recognize that the small number of participants may limit the generalizability of our findings. For example, our population comprised mostly of Caucasians and the socio-demographic factors were relatively homogeneous. However, the groups included patients and caregivers who underwent autologous or allogeneic HCT, representing both types of transplants. In future work we may want to consider eliciting feedback from patients and caregivers separately to detect any potential differences in their needs.

Second, as seen in our previous qualitative focus group study,26 our findings may have been influenced by selection bias. The patients and caregivers recruited to this study were those who already went through the HCT process, survived, and whose physical stamina was strong enough to attend the Design Groups. These relatively healthier patients may not reflect the opinions and perspectives of patients and caregivers who had a more complicated and poor transplant course. Moreover, it is possible that user perspectives would have been different if patients and caregivers actively undergoing the HCT process were included as participants in the Design Groups. Understanding user experience with actual use of data is an important consideration for recognizing risks and benefits of a portable health IT device, and we will monitor for this in the future Phase 3 portion of the research project when the BMT Roadmap system will be evaluated in real use.

Third, the Design Group moderators included researchers who were familiar with the systems’ contents and functions, and were immediately available to participants if they faced any difficulties with executing any of the functions. It is possible, in the inpatient setting, when patients and caregivers are left to use the tool at their leisure they could experience anxiety and frustration in the lack of immediate availability of “tech support.” This will also be addressed in the future Phase 3 portion of the research project when the BMT Roadmap system will be evaluated in real use.

CONCLUSIONS

From the patient and caregiver perspectives, the BMT Roadmap system was considered a useful tool. The findings from Design Group I led to design changes that were then examined in Design Group II. Additional changes were made thereafter that led to an improved, functional BMT Roadmap product. This unique research process and the findings reported herein included data generated from patients, caregivers, providers, and researchers as partners. Collectively, the data informed the design and development of the tool, which will be tested as an intervention in the Pediatric HCT population at our center in the fall of 2015 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02409121). The BMT Roadmap has the potential to offer users with an improved understanding of their healthcare as well as provide a platform for improved communication among patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers. The challenge is developing a health IT tool that is accessible and functional for users - tailored to their needs. In the design and development of the BMT Roadmap, in the present study, our aim was to involve users early in this process in order to implement and evaluate the processes in a more effective and meaningful manner. The main benefit of this study was the input of user perspectives in the design of the tool. It should be possible for our BMT Roadmap software to be implemented at other institutions, including those using Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI). With the increasing use of health IT resulting from government incentives, and the increasing importance of satisfaction and value-based care,40 designing innovative user-centered health IT tools is imperative.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

HCT patients and caregivers experience numerous information needs and challenges

Health IT has the potential to improve coordination of care and communication

User-centered Design Groups were feasible to conduct in HCT patient and caregivers

Design Groups resulted in changes that led to an improved health IT tool

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients, their families, and the clinical personnel who participated in this study. The work herein was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (“Exploratory and Developmental Grant to Improve Health Care Quality through Health Information Technology”: 1R21HS023613). SWC is an A. Alfred Taubman Institute/Edith Briskin/SKS Foundation Emerging Scholar and is also supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (1K23AI091623).

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP

M.M. (Health Informatics M.S. candidate) collected and analyzed data, and drafted and approved the manuscript; E.K. (Human-Computer Interaction [HCI] Ph.D. candidate) collected and analyzed data, and edited and approved the manuscript; H.D., R.F., K.M., D.O. (Health Communications Research Team) collected data and approved the manuscript; L.A. oversaw the Health Communications Research Team and approved the manuscript; M.T. advised on the study concept and approved the manuscript; M.A. designed the study, analyzed data, edited and approved the manuscript; D.A.H. designed the study, analyzed data, and drafted and approved the manuscript; S.W.C. designed the study, cared for patients, collected and analyzed data, and drafted and approved the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ozkaynak M, Brennan PF, Hanauer DA, et al. Patient-centered care requires a patient-oriented workflow model. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2013 Jun;20(e1):e14–16. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Annals of internal medicine. 2006 May 16;144(10):742–752. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine . Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. The New England journal of medicine. 2006 Apr 27;354(17):1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stetz KM, McDonald JC, Compton K. Needs and experiences of family caregivers during marrow transplantation. Oncology nursing forum. 1996 Oct;23(9):1422–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fife B, Monahan P, Abonour R, Wood L, Stump T. Adaptation of family caregivers during the acute phase of adult BMT. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2009;43(12):959–966. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarzian AJ, Iwata PA, Cohen MZ. Autologous bone marrow transplantation: the patient’s perspective of information needs. Cancer nursing. 1999 Apr;22(2):103–110. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199904000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winkelstein P. eHealth: Legal, Ethical and Governance Challenge. Springer; Berline Heidelberg: 2013. Medicine 2.0: Ethical Challenges of Social Media for the Health Profession; pp. 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ricciardi L, Mostashari F, Murphy J, Daniel JG, Siminerio EP. A national action plan to support consumer engagement via e-health. Health affairs. 2013 Feb;32(2):376–384. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang PC, Ash JS, Bates DW, Overhage JM, Sands DZ. Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2006 Mar-Apr;13(2):121–126. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delbanco T, Walker J, Darer JD, et al. Open notes: doctors and patients signing on. Annals of internal medicine. 2010 Jul 20;153(2):121–125. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-2-201007200-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyles CR, Sarkar U, Ralston JD, et al. Patient-provider communication and trust in relation to use of an online patient portal among diabetes patients: The Diabetes and Aging Study. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2013 Nov-Dec;20(6):1128–1131. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran CR. Patient Portals and Patient Engagement: A State of the Science Review. Journal of medical Internet research. 2015;17(6):e148. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruse CS, Bolton K, Freriks G. The effect of patient portals on quality outcomes and its implications to meaningful use: a systematic review. Journal of medical Internet research. 2015;17(2):e44. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Hoerbst A. The impact of electronic patient portals on patient care: a systematic review of controlled trials. Journal of medical Internet research. 2012;14(6):e162. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prey JE, Woollen J, Wilcox L, et al. Patient engagement in the inpatient setting: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2014 Jul-Aug;21(4):742–750. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Versel N. Healthcare IT News. Washington: 2014. Portals aren’t just for outpatients. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greysen R, Rajkomar A, Jacolbia R, et al. Bedside Coaching Improves Patient Engagement through PAtient Portals During and after Hospital Care. Paper presented at: Medicine 2.0; 2014–06–01, 2014; Maui, Hawaii, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epic Systems. [Accessed July 8, 2015];Mobile Applications and Portals. https://http://www.epic.com/software-phr.php.

- 20.Cegala DJ, Post DM. The impact of patients’ participation on physicians’ patient-centered communication. Patient education and counseling. 2009 Nov;77(2):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byczkowski TL, Munafo JK, Britto MT. Family perceptions of the usability and value of chronic disease web-based patient portals. Health informatics journal. 2014 Jun;20(2):151–162. doi: 10.1177/1460458213489054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britto MT, Jimison HB, Munafo JK, Wissman J, Rogers ML, Hersh W. Usability testing finds problems for novice users of pediatric portals. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2009 Sep-Oct;16(5):660–669. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawkins RP, Kreuter M, Resnicow K, Fishbein M, Dijkstra A. Understanding tailoring in communicating about health. Health education research. 2008 Jun;23(3):454–466. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreuter MW, Farrell DW, Olevitch LR, Brennan LK. Tailoring health messages: Customizing communication with computer technology. Routledge: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Northouse L, Schafenacker A, Barr KL, et al. A tailored web-based psychoeducational intervention for cancer patients and their family caregivers. Cancer nursing. 2014;37(5):321–330. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keusch F, Rao R, Chang L, Lepkowski J, Reddy P, Choi SW. Participation in Clinical Research: Perspectives of Adult Patients and Parents of Pediatric Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2014/10. 2014;20(10):1604–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaziunas E, Buyuktur AG, Jones J, Choi SW, Hanauer DA, Ackerman MS. Transition and Reflection in the Use of Health Information. Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing - CSCW ‘15; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaziunas E, Hanauer D, Ackerman M, Choi S. Identifying unmet information needs in the inpatient setting to increase patient and caregiver engagement in the context of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association. 2015 doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv116. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poole ES. HCI and mobile health interventions. Translational behavioral medicine. 2013;3(4):402–405. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0214-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarver WL, Menachemi D. The Impact of Health Information Technology on Cancer Care across the Continuum: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2015 Jul 15; doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baudendistel I, Winkler E, Kamradt M, et al. Personal electronic health records: understanding user requirements and needs in chronic cancer care. Journal of medical Internet research. 2015;17(5):e121. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephens J, Allen JK, Dennison Himmelfarb CR. “Smart” coaching to promote physical activity, diet change, and cardiovascular health. The Journal of cardiovascular nursing. 2011 Jul-Aug;26(4):282–284. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31821ddd76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phipps S, Dunavant M, Lensing S, Rai SN. Patterns of distress in parents of children undergoing stem cell transplantation. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2004 Sep;43(3):267–274. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooke L, Grant M, Gemmill R. Discharge needs of allogeneic transplantation recipients. Clinical journal of oncology nursing. 2012 Aug;16(4):E142–149. doi: 10.1188/12.CJON.E142-E149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warren-Findlow J, Seymour RB, Shenk D. Intergenerational transmission of chronic illness self-care: results from the caring for hypertension in African American families study. The Gerontologist. 2011 Feb;51(1):64–75. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bollinger LM, Nire KG, Rhodes MM, Chisolm DJ, O’Brien SH. Caregivers’ perspectives on barriers to transcranial Doppler screening in children with sickle-cell disease. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2011 Jan;56(1):99–102. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pennarola BW, Rodday AM, Mayer DK, et al. Factors associated with parental activation in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Medical care research and review : MCRR. 2012 Apr;69(2):194–214. doi: 10.1177/1077558711431460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Social science & medicine. 2000 Oct;51(7):1087–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed on January 24, 2014];Health IT financial incentive program. Meaningful Use. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Meaningful_Use.html.

- 40.LeMaistre CF, Farnia SH. Goals for Pay for Performance in Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Primer. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2015 Aug;21(8):1367–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Epstein RM, Street RLJ. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williamson K. Where one size does not fit all: understanding the needs of potential users of a portal to breast cancer knowledge online. Journal of health communication. 2005 Sep;10(6):567–580. doi: 10.1080/10810730500228961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weitzman ER, Kaci L, Mandl KD. Acceptability of a personally controlled health record in a community-based setting: implications for policy and design. Journal of medical Internet research. 2009;11(2):e14. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Earnest MA, Ross SE, Wittevrongel L, Moore LA, Lin CT. Use of a patient-accessible electronic medical record in a practice for congestive heart failure: patient and physician experiences. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2004 Sep-Oct;11(5):410–417. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyles C, Schillinger D, Sarkar U. Connecting the Dots: Health Information Technology Expansion and Health Disparities. PLoS Med. 2015;12(7):e1001852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Segall N, Saville JG, L’Engle P, et al. Usability evaluation of a personal health record. AMIA ... Annual Symposium proceedings / AMIA Symposium AMIA Symposium. 2011;2011:1233–1242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klasnja P, Civan Hartzler A, Unruh KT, Pratt W. Blowing in the wind: unanchored patient information work during cancer care. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2010; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.