Abstract

AIM: To clone ureB gene from a clinical isolate of Helicobacter pylori and construct a prokaryotic expression system of the gene and identify immunity of the expressed recombinant protein.

METHODS: ureB gene from a clinical H pylori strain Y06 was amplified by the high fidelity polymerase chain reaction technique. The target DNA fragment amplified from ureB gene was sequenced after T-A cloning. Prokaryotic recombinant expression vector pET32a inserted with ureB gene (pET32a-ureB) was constructed. The expression of recombinant UreB protein (rUreB) in E. coli BL21DE3 induced by isopropylthio-β-D-galactoside (IPTG) at different concentrations was examined by SDS-PAGE. Western blot using commercial antibodies against whole cell of H pylori and an immunodiffusion assay using a self-prepared rabbit anti-rUreB antibody were applied to determine immunity of the target recombinant protein. ELISA was used to detect the antibody against rUreB in sera of 125 H pylori infected patients and to examine rUreB expression in 109 H pylori isolates.

RESULTS: In comparison with the reported corresponding sequences, the nucleotide sequence homology of the cloned ureB gene was from 96.88-97.82% while the homology of its putative amino acid sequence was as high as 99.65-99.82%. The rUreB output expressed by pET32a-ureB-BL21DE3 was approximate 30% of the total bacterial proteins. rUreB specifically combined with the commercial antibodies against whole cell of H pylori and strongly induced rabbits to produce antibody with a 1:8 immunodiffusion titer after the animals were immunized with the recombinant protein. Serum samples from all H pylori infected patients were positive for UreB antibody and UreB expression were detectable in all tested H pylori isolates.

CONCLUSION: A prokaryotic expression system with high expression efficiency of H pylori ureB gene was successfully established. The expressed rUreB showed qualified immunoreactivity and antigenicity. High frequencies of UreB expression in different H pylori isolates and specific antibody against UreB in sera of H pylori infected patients indicate that UreB is an excellent antigen candidate for developing H pylori vaccine.

INTRODUCTION

In China, chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer are two most common gastric diseases, and gastric cancer is one of the malignant tumors with high mortalities and morbidities[1-34]. Helicobacter pylori, a microaerophilic, spiral and Gram-negative bacterium, is recognized as a human-specific gastric pathogen that colonizes the stomachs of at least half of the world’s populations[35]. Most infected individuals are asymptomatic. However, in some subjects, H pylori infection causes acute/chronic gastritis or peptic ulceration. Furthermore, the infection is also a high risk factor for the development of gastric adenocarcinoma, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma and primary gastric non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma[36-43]. Recently, direct evidence that H pylori causes gastric carcinoma in an animal model has been reported[44-46]. Immunization against the bacterium represents a cost-effective strategy to prevent H pylori-associated peptic ulcer disease and to reduce the incidence of global gastric cancer[47]. The selection of antigenic targets is critical in the design of H pylori vaccine. So far, no vaccine preventing H pylori infection was commercially available. Almost all H pylori strains produce a special urease decomposing urea and forming ammonia, which is harmful to gastric mucosa. Moreover, a high pH value is benefit for organisms to colonize the stomach. Urease is composed of 4 subunits, A, B, C and D. The subunit B (UreB), a peptide with 569 amino acid residuals encoded by ureB gene, has been demonstrated to show the strongest antigenicity and protection among all known H pylori proteins[48-50]. Furthermore, almost all H pylori isolates have ureB gene and express UreB protein, and their nucleotide and putative amino acid sequence homologies are as high as approximate 95%[51-53]. These data strongly indicate that UreB is a potential antigen candidate for H pylori vaccine. In this study, a recombinant prokaryotic vector responsible for the recombinant UreB protein (rUreB) expression was constructed. Immunogenicity and immunoreactivity of rUreB were further examined. Furthermore, rUreB was used as an antigen in ELISA to detect specific antibody in sera from H pylori infected patients, and rabbit anti-rUreB serum was prepared to examine the UreB expression in different H pylori isolates. The results of this study will supply further experimental foundation for the development of H pylori vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

A clinical strain of H pylori, provisionally named Y06, which was well-characterized by the Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, College of Medical Science, Zhejing University, was used in this study. A plasmid pET32a (Novagen, Madison, USA) and E. coli BL21 DE3 (Novagen, Madison, USA) were used as the expression vector and host cell, respectively. Primers for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification were synthezed by BioAsia (Shanghai, China). A Taq-plus high fidelity PCR kit and restriction endonucleases were purchased from TaKaRa (Dalian, China). The T-A Cloning kit and sequencing service were provided by BBST (Shanghai, Ch ina) . DAKO (Glostrup , Denmark) an d Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, USA) supplied rabbit antiserum against whole cell of H pylori, HRP-labeling sheep anti-rabbit IgG and anti- human IgG antibodies, respectively. Agents for H pylori isolation and identification were purchased from bioMérieux (Marcy I’Etoile, France). Overall, 126 patients (86 males and 40 females; age range: from 6-78 yr; mean age: 40.5 yr) who were referred for upper endoscopy from 4 different hospitals in Hangzhou during the period between December 2001 and June 2002 and had H pylori isolated from gastric mucosa were included in the study. All patients gave a written informed content. Of the 126 patients, 68 were endoscopically diagnosed as having chronic gastritis (CG, 48 superficial, 10 active and 10 atrophic gastritis), and 58 as having peptic ulcer disease (PUD, 12 gastric, 40 duodenal, and 6 gastric and duodenal ulcer). None of the patients had taken nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antacids and antibiotics during the 2-wk before seeking medical advice. At the same time, serum specimens were also collected from these patients.

Isolation and identification of H pylori

Each gastric biopsy taken during endoscopy was homogenized with a tissue grinder and then inoculated on Columbia agar plates supplemented with 80 mL/L sheep blood, 5 g/L cyclodextrin, 5 mg/L trimethoprim, 10 mg/L vancomycin, 2.5 mg/L amphotericin B and 2500 U/L cefsoludin. The plates were incubated at 37 °C under microaerobic conditions (50 mL/LO2, 100 mL/LCO2 and 850 mL/LN2) for 3 to 5 d. A bacterial isolate was identified as H pylori according to typical Gram stain morphology, biochemical tests positive for urease and oxidase, and agglutination with the commercial rabbit antibodies against whole cell of H pylori. One of the isolated strains, named as Y06 that had typical characteristics of H pylori, was selected for further experiments.

Preparation of DNA template

Genomic DNA of H pylori strain Y06 was prepared by the routine phenol-chloroform method and DNase-free RNase treatment. The obtained DNA was dissolved in TE buffer, and its concentration and purity were determined by ultraviolet spectrophotometry[54].

Polymerase Chain Reaction

Primers were designed to amplify the whole sequence of ureB gene from strain Y06 based on the published sequences and reading frames[51-53]. The sequences of ureB sense primer with an endonuclease site of EcoRV and antisense primer with an endonuclease site of Xho I were 5'-GGAGATATCATGATTAGCAGAAAAG AATATGTTTC-3' and 5'-GGACTCGAGCTAGAAAATGCTAAAGAGTT GTGC-3', respectively. Total volume per PCR was 100 μL containing 2.5 mol/L each dNTP, 250 nmol/L each of the 2 primers, 15 mol/L MgCl2, 3.0 U Taq-plus polymerase, 100 ng DNA template and 1 × PCR buffer (pH8.3). The parameters for PCR were 94 °C for 5 min, × 1; 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 120 s, × 10; 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 130 s (10 s addition for each of the following cycles), × 20; and then 72 °C for 12 min, × 1. The results of PCR were observed under UV light after electrophoresis in 10 g/L agarose, pre-stained with ethidium bromide. The expected size of target amplification fragment was 1 704 bp.

Cloning and sequencing

The target amplification DNA fragment from ureB gene was cloned into pUCm-T vector (pUCm-T-ureB) by using the T-A Cloning kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The recombinant plasmid was amplified in E. coli strain DH5α and then extracted by Sambrook’s method[54]. A professional company (BBST) was responsible for nucleotide sequence analysis of the inserted fragment. Two E. coli DH5α strains containing pUCm-T-ureB and expression vector pET32a, respectively, were subcultured in LB medium. Then the plasmids were extracted[54] and digested with EcoRV and XhoI, respectively. The ureB target fragments and pET32a were recovered for ligation. The recombinant expression vector pET32a-ureB was transformed into E. coli BL21DE3, which was named as pET32a- ureB-BL21DE3. The target ureB gene fragment inserted in pET32a plasmid was sequenced again.

Expression and identification of the fusion protein

pET32a-ureB-BL21DE3 was rotatively cultured in LB medium at 37 °C and induced by isopropylthio-β-D-galactoside (IPTG) at different concentrations of 1.0, 0.5 and 0.1 mmol/L. The supernatant and precipitate were separated by centrifugation after the bacterial pallet was ultrasonically broken (300 V, 5 s × 3). The molecular mass and output of rUreB were measured by SDS-PAGE. The expressed rUreB was collected by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. The commercial rabbit antiserum against whole cell of H pylori and HRP-labeling sheep anti-rabbit IgG were used as the first and second antibodies, respectively, to determine the immunoreactivity of rUreB by Western blot. Rabbits were immunized with rUreB to prepare the antiserum, and an immunodiffusion assay was applied to determine the antigenicity of rUreB.

ELISA

By using rUreB as antigen at the coated concentration of 20 μg/mL, a patient serum sample (1:400 dilution) as the first antibody and HRP-labeling sheep anti-human IgG (1:4000 dilution) as the second antibody, the specific antibody against UreB in sera from the 126 patients infected with H pylori were detected by ELISA. The result of ELISA for a patient’s serum sample was considered as positive if the A value at 490 nm (A490) was over the mean plus 3 SD of 6 negative serum samples[55]. UreB expression in H pylori isolates was examined by ELISA using the ultrasonic supernatant of each isolate (50 μg/mL) as a coated protein antigen, the self-prepared rabbit anti-rUreB serum (1:2000 dilution) as the first antibody and HRP-labeling sheep anti-rabbit IgG (1:3000 dilution) as the second antibody. The result of ELISA for a H pylori ultrasonic supernatant sample was considered as positive if its A490 value was over the mean plus 3 SD of 6 ultrasonic supernatant samples at the same protein concentration of E. coli ATCC 25922[55].

Data analysis

The nucleotide sequences of the cloned ureB gene inserted in the two recombinant plasmid vectors were compared for homology with the 3 published ureB gene sequences (NC000915, M60398, X57132, AB032429)[51-53] by using a molecular biological analysis soft ware.

RESULTS

PCR

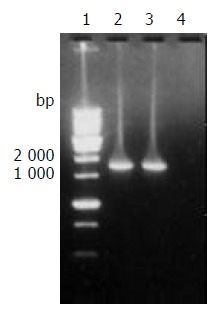

The target fragment of ureB gene with the expected size amplified from DNA template of H pylori stain Y06 is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The target fragment of ureB gene amplified from H pylori strain Y06 DNA. Lane 1, 1 kb DNA marker (BBST); lanes 2 and 3, the target amplification fragment of ureB gene from genomic DNA of H pylori strain Y06; lane 4: blank control.

Nucleotide sequence analysis

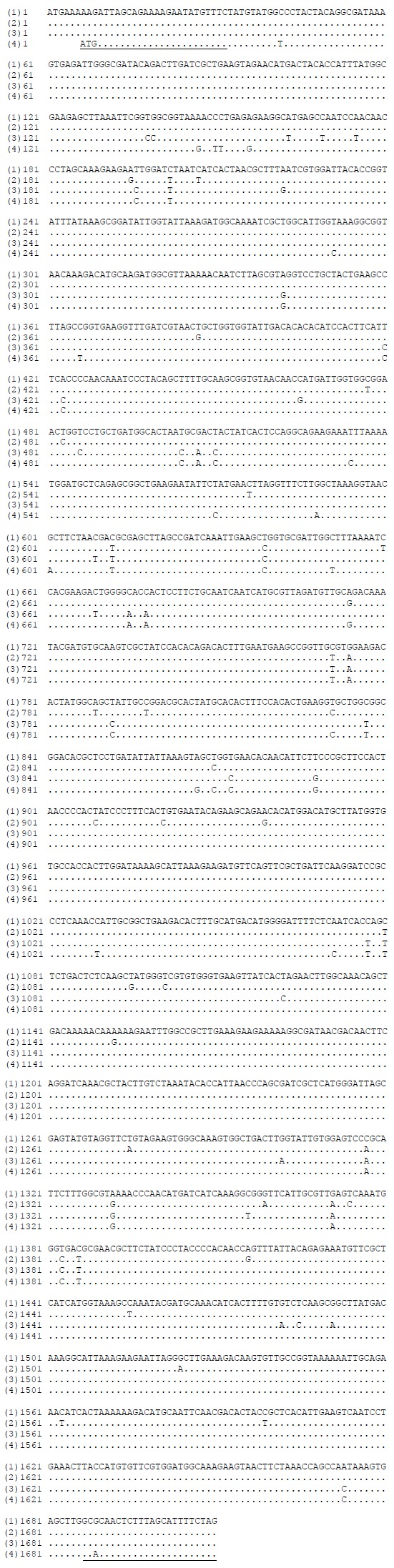

The nucleotide sequences of ureB gene in pUCm-T-ureB and pET32a-ureB were completely same. The homologies of the nucleotide and putative amino acid sequences of the cloned ureB gene compared with the published ureB gene sequences[51-53] were from 96.88% to 97.82% and from 99.65% to 99.82%, respectively (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Homology comparison of the cloned and reported H pylori ureB nucleotide sequences.(1)-(3): the reported sequences from GenBank (No. NC000915, strain 26695; No. M60398, X57132; No. AB032429); (4): the sequencing result of H pylori strain Y06 ureB gene. Underlined areas indicate the positions of primer sequences.

Figure 3.

Homology comparison of the putative amino acid sequences of the cloned and reported H pylori ureB gene. [1]-[3]: the reported sequences from GenBank (No. NC000915, strain 26695; No. M60398, X57132; No. AB032429); [4]: the putative amino acid sequence of the cloned H pylori strain Y06 ureB gene.

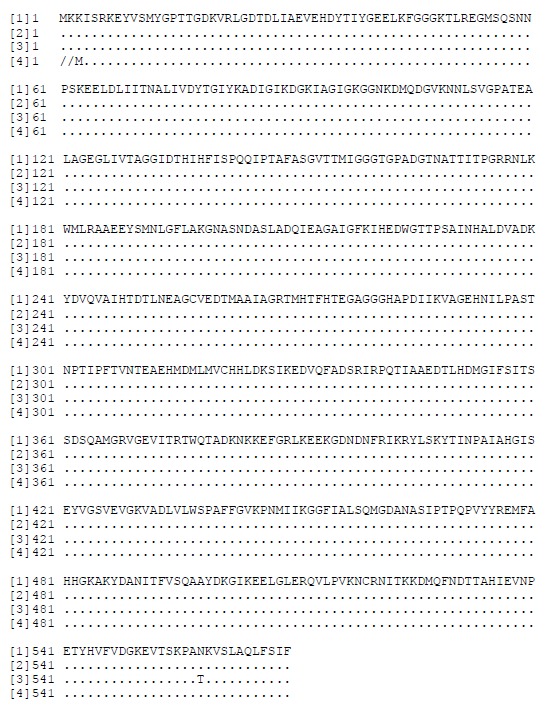

Expression of the target fusion protein

IPTG at concentrations of 1.0, 0.5 and 0.1 mmol/L efficiently induced the expression of rUreB in the pET32a-ureB-BL21DE3 system. The product of rUreB was mainly presented in ultrasonic precipitates and the output was approximate 30% of the total bacterial proteins (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Expression of rUreB induced by IPTG at different concentrations. Lane 1, molecular mass marker; lanes 2-4, IPTG at 1.0, 0.5, and 0.1 mmol/L, respectively; lanes 5 and 6, bacterial precipitate and supernatant with IPTG at 1 mmol/L , respectively; lane 7, control.

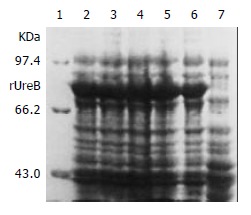

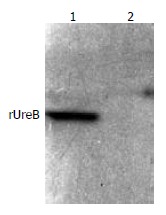

Immunoreactivity and antigenicity of rUreB

The commercial rabbit antibodies against the whole cell of H pylori combined with rUreB as confirmed by Western blot (Figure 5), and the titer demonstrated by immunodiffusion assay between rUreB and self-prepared rabbit anti-rUeB serum was 1:8.

Figure 5.

Western blot result of commercial rabbit antibodies against the whole cell of H pylori and rUreB. Lane 1, rUreB; lane 2, blank.

ELISA

Since the mean ± SD of A490 values of the 6 negative serum samples was 0.173 ± 0.025, the positive reference value for the specific antibody detection in patients’ sera was 0.248. According to the reference value, 100% (125/125, one serum sample was contaminated) of the tested patients’ serum samples were positive for antibody against rUreB with an A490 value range of 0.27-1.97. Since the mean ± SD of A490 of the 6 negative bacterial controls was 0.170 ± 0.026, the positive reference value was 0.248 for UreB detection in H pylori isolates. According to the reference value, 100% (109/109, the other 17 isolates could not be revived from -70 °C) of the tested H pylori isolates were positive for rUreB epitopes with an A490 value range of 0.47-1.93.

DISCUSSION

Amoxciilin and metronidazole, used as routinely therapeutic antibiotics in a triple therapy, effectively eradicate H pylori infection in vivo[56-58]. However, there are problems such as side effects, emergence of drug resistance and re-infection after withdrawal of antibiotics, etc. It is generally considered that inoculation with H pylori vaccine is of value in prevention and control of H pylori infection. Previous studies have demonstrated that inoculation with sonic-broken H pylori resist the challenge of live H pylori and even eliminate existing infection of H pylori in animal models. But high nutrition requirements, poor growth after several passages, easy contamination during cultivation and difficulty in bacterial conservation make whole cell vaccine of H pylori impracticable. Genetic engineering vaccine seems to be a possible pathway for developing H pylori vaccine. UreB, used as a candidate antigen for H pylori genetic engineering vaccine, has advantages of high sequence conservation, a high frequency of distribution and large expression in different isolates, strong antigenicity due to its big molecular mass, granular structure and exposure on the surface of bacteria[59,60].

In the present study, a prokaryotic expression system of rUreB was constructed. In comparison with the three published ureB gene sequences[51-53], high homologies of 96.88-97.82% and 99.65-99.82% of the nucleotide and putative amino acid sequences of the cloned ureB gene from the H pylori strain Y06, respectively, were found, whereas homologies were 96.78-97.83% and 99.82-100%, respectively, among the ureB genes from the 3 H pylori strains. These data indicate that the mutation level of ureB gene from different H pylori strains is considerably low.

The results of SDS-PAGE performed in this study demonstrate that the constructed prokaryotic expression system pET32a-ureB-BL21DE3 efficiently produces rUreB even at the concentration of IPTG as low as 0.1 mmol/L. rUreB mainly is presented in the form of dissoluble inclusion body and appears in the supernatant of culture only in a small amount. The output of rUreB is relatively high (approximately 30% of the total bacterial proteins), which is beneficial to industrial production.

Western blot assay performed in this study confirms that the commercial rabbit antiserum against whole cell of H pylori recognizes and combines to rUreB, indicating a high immunoreactivity of the recombinant protein. The immunodiffusion assay also demonstrates that rUreB efficiently induces rabbit to produce specific antibody with a higher titer, exhibiting a favorable antigenicity of the recombinant protein.

The findings by ELISA that all the tested H pylori isolates expressed UreB and all the tested sera from H pylori infected patients were positive for UreB-specific antibody indicate the universal existence of UreB in H pylori strains and a high frequency of UreB-specific antibody in human, which supports application of rUreB as an antigen for the development of H pylori vaccine.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the people’s Hospital of Zhejiang, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University and the Affiliated Run Run Shaw Hospital of Zhejiang University in Hangzhou for kindly providing gastric biopsies in this study.

Footnotes

Supported by the Excellent Young Teacher Fund of Chinese Education Ministry and the General Science and Technology Research Plan of Zhejiang Province, No. 001110438

Edited by Xia HHX and Xu FM

References

- 1.Ye GA, Zhang WD, Liu LM, Shi L, Xu ZM, Chen Y, Zhou DY. Helicobacter pylori vacA gene polymorphism and chronic gastrosis. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:593–595. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu SY, Pan XZ, Peng XW, Shi ZL. Effect of Hp infection on gastric epithelial cell kinetics in stomach diseases. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:760–762. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Z, Yuan Y, Gao H, Dong M, Wang L, Gong YH. Apoptosis, proliferation and p53 gene expression of H. pylori associated gastric epithelial lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:779–782. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i6.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu XL, Qian KD, Tang XQ, Zhu YL, Du Q. Detection of H.pylori DNA in gastric epithelial cells by in situ hybridization. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:305–307. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i2.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao YL, Xu B, Song YG, Zhang WD. Overexpression of cyclin E in Mongolian gerbil with Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric precancerosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:60–63. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo DL, Dong M, Wang L, Sun LP, Yuan Y. Expression of gastric cancer-associated MG7 antigen in gastric cancer, precancerous lesions and H. pylori -associated gastric diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:1009–1013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i6.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng ZS, Liang ZC, Liu MC, Ouyang NT. Studies on gastric epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis in Hp associated gas-tric ulcer. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:218–219. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiyama T, Haruma K, Kitadai Y, Miyamoto M, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Shimamoto F, Kajiyama G. B-cell monoclonality in Helicobacter pylori-associated chronic atrophic gastritis. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:232–237. doi: 10.1007/s004280000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harry XH. Association between Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: current knowledge and future research. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4:93–96. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v4.i2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quan J, Fan XG. Progress in experimental research of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:1068–1069. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu HF, Liu WW, Fang DC. Study of the relationship between apoptosis and proliferation in gastric carcinoma and its pre-cancerous lesion. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:649–651. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu ZH, Xia ZS, He SG. The effects of ATRA and 5-Fu on telomerase activity and cell growth of gastric cancer cells in vitro. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2000;8:669–673. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tu SP, Zhong J, Tan JH, Jiang XH, Qiao MM, Wu YX, Jiang SH. Induction of apoptosis by arsenic trioxide and hydroxy camptothecin in gastriccancer cells in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:532–539. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i4.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai L, Yu SZ, Zhang ZF. Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of gastric cancer in Changle County,Fujian Province,China. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:374–376. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i3.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao XX, Yin L, Zhang JY, Bai WY, Li YM, Sun ZC. HTERT expression and cellular immunity in gastric cancer and precancerosis. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:508–512. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu AG, Li SG, Liu JH, Gan AH. Function of apoptosis and expression of the proteins Bcl-2, p53 and C-myc in the development of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:403–406. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i3.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Lan M, Shi YQ, Lu J, Zhong YX, Wu HP, Zai HH, Ding J, Wu KC, Pan BR, et al. Differential display of vincristine-resistance-related genes in gastric cancer SGC7901 cell. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:54–59. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu JR, Li BX, Chen BQ, Han XH, Xue YB, Yang YM, Zheng YM, Liu RH. Effect of cis-9, trans-11-conjugated linoleic acid on cell cycle of gastric adenocarcinoma cell line (SGC-7901) World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:224–229. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i2.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai L, Yu SZ. A molecular epidemiologic study on gastric cancer in Changle, Fujian Province. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:652–655. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao GL, Yang Y, Yang SF, Ren CW. Relationship between pro-liferation of vascular andothelial cells and gastric cancer. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2000;8:282–284. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xue XC, Fang GE, Hua JD. Gastric cancer and apoptosis. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:359–361. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niu WX, Qin XY, Liu H, Wang CP. Clinicopathological analysis of patients with gastric cancer in 1200 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:281–284. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li XY, Wei PK. Diagnosis of stomach cancer by serum tumor markers. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:568–570. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang DC, Yang SM, Zhou XD, Wang DX, Luo YH. Telomere erosion is independent of microsatellite instability but related to loss of heterozygosity in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:522–526. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i4.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgner A, Miehlke S, Stolte M, Neubauer A, Alpen B, Thiede C, Klann H, Hierlmeier FX, Ell C, Ehninger G, et al. Development of early gastric cancer 4 and 5 years after complete remission of Helicobacter pylori associated gastric low grade marginal zone B cell lymphoma of MALT type. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:248–253. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i2.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng DJ. progress of gastric cancer etiology: N-nitrosamides 1999s. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:613–618. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i4.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu ZM, Shou NH, Jiang XH. Expression of lung resistance protein in patients with gastric carcinoma and its clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:433–434. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i3.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo CQ, Wang YP, Liu GY, Ma SW, Ding GY, Li JC. Study on Helicobacter pylori infection and p53, c-erbB-2 gene expression in carcinogenesis of gastric mucosa. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:313–315. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai L, Yu SZ, Ye WM, Yi YN. Fish sauce and gastric cancer: an ecological study in Fujian Province,China. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:671–675. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i5.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xue FB, Xu YY, Wan Y, Pan BR, Ren J, Fan DM. Association of H. pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a Meta analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:801–804. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i6.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang RT, Wang T, Chen K, Wang JY, Zhang JP, Lin SR, Zhu YM, Zhang WM, Cao YX, Zhu CW, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer: evidence from a retrospective cohort study and nested case-control study in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:1103–1107. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i6.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hua JS. Effect of Hp: cell proliferation and apoptosis on stom-ach cancer. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:647–648. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu DH, Zhang XY, Fan DM, Huang YX, Zhang JS, Huang WQ, Zhang YQ, Huang QS, Ma WY, Chai YB, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its role in oncogenesis of human gastric carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:500–505. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i4.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao WX, Ou JM, Fei XF, Zhu ZG, Yin HR, Yan M, Lin YZ. Methionine-dependence and combination chemotherapy on human gastric cancer cells in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:230–232. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michetti P, Kreiss C, Kotloff KL, Porta N, Blanco JL, Bachmann D, Herranz M, Saldinger PF, Corthésy-Theulaz I, Losonsky G, et al. Oral immunization with urease and Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin is safe and immunogenic in Helicobacter pylori-infected adults. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:804–812. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suganuma M, Kurusu M, Okabe S, Sueoka N, Yoshida M, Wakatsuki Y, Fujiki H. Helicobacter pylori membrane protein 1: a new carcinogenic factor of Helicobacter pylori. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6356–6359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Suekane H, Takeshita M, Hizawa K, Kawasaki M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Iida M, Fujishima M. Predictive value of endoscopic ultrasonography for regression of gastric low grade and high grade MALT lymphomas after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 2001;48:454–460. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgner A, Miehlke S, Fischbach W, Schmitt W, Müller-Hermelink H, Greiner A, Thiede C, Schetelig J, Neubauer A, Stolte M, et al. Complete remission of primary high-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2041–2048. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.7.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N, Badrinath S. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the ulcer recurrence rate after simple closure of perforated duodenal ulcer: retrospective and prospective randomized controlled studies. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1054–1058. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhuang XQ, Lin SR. Progress in research on the relationship between Hp and stomach cancer. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2000;8:206–207. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao HJ, Yu LZ, Bai JF, Peng YS, Sun G, Zhao HL, Miu K, L XZ, Zhang XY, Zhao ZQ. Multiple genetic alterations and behavior of cellular biology in gastric cancer and other gastric mucosal lesions: H.pylori infection, histological types and staging. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:848–854. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i6.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao YL, Zhang WD. Relation between Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:1045–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goto T, Nishizono A, Fujioka T, Ikewaki J, Mifune K, Nasu M. Local secretory immunoglobulin A and postimmunization gastritis correlate with protection against Helicobacter pylori infection after oral vaccination of mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2531–2539. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2531-2539.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe T, Tada M, Nagai H, Sasaki S, Nakao M. Helicobacter pylori infection induces gastric cancer in mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:642–648. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Honda S, Fujioka T, Tokieda M, Satoh R, Nishizono A, Nasu M. Development of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric carcinoma in Mongolian gerbils. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4255–4259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hatzifoti C, Wren BW, Morrow WJ. Helicobacter pylori vaccine strategies--triggering a gut reaction. Immunol Today. 2000;21:615–619. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01753-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rupnow MF, Owens DK, Shachter R, Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori vaccine development and use: a cost-effectiveness analysis using the Institute of Medicine Methodology. Helicobacter. 1999;4:272–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1999.99311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corthésy-Theulaz I, Porta N, Glauser M, Saraga E, Vaney AC, Haas R, Kraehenbuhl JP, Blum AL, Michetti P. Oral immunization with Helicobacter pylori urease B subunit as a treatment against Helicobacter infection in mice. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:115–121. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pappo J, Thomas WD, Kabok Z, Taylor NS, Murphy JC, Fox JG. Effect of oral immunization with recombinant urease on murine Helicobacter felis gastritis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1246–1252. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1246-1252.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, Clayton RA, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, Ketchum KA, Klenk HP, Gill S, Dougherty BA, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akada JK, Shirai M, Takeuchi H, Tsuda M, Nakazawa T. Identification of the urease operon in Helicobacter pylori and its control by mRNA decay in response to pH. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:1071–1084. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Labigne A, Cussac V, Courcoux P. Shuttle cloning and nucleotide sequences of Helicobacter pylori genes responsible for urease activity. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1920–1931. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.1920-1931.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning, A Labo-ratory Manual [M]. 2nd edition. New York: Cold Spring HarborLaboratory Press. 1989, pp1.21-1.52, 2.60-2.80, 7.3-7.35, 9.14-9.22 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen Y, Wang J, Shi L. [In vitro study of the biological activities and immunogenicity of recombinant adhesin of Heliobacter pylori rHpaA] Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2001;81:276–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McMahon BJ, Hennessy TW, Bensler JM, Bruden DL, Parkinson AJ, Morris JM, Reasonover AL, Hurlburt DA, Bruce MG, Sacco F, et al. The relationship among previous antimicrobial use, antimicrobial resistance, and treatment outcomes for Helicobacter pylori infections. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:463–469. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-6-200309160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong WM, Gu Q, Wang WH, Fung FM, Berg DE, Lai KC, Xia HH, Hu WH, Chan CK, Chan AO, et al. Effects of primary metronidazole and clarithromycin resistance to Helicobacter pylori on omeprazole, metronidazole, and clarithromycin triple-therapy regimen in a region with high rates of metronidazole resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:882–889. doi: 10.1086/377206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chi CH, Lin CY, Sheu BS, Yang HB, Huang AH, Wu JJ. Quadruple therapy containing amoxicillin and tetracycline is an effective regimen to rescue failed triple therapy by overcoming the antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:347–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dieterich C, Bouzourène H, Blum AL, Corthésy-Theulaz IE. Urease-based mucosal immunization against Helicobacter heilmannii infection induces corpus atrophy in mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6206–6209. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6206-6209.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ernst JD. Toward the development of antibacterial vaccines: report of a symposium and workshop. Organizing Committee. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1295–1302. doi: 10.1086/313484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]