Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the association of pre-treatment 13C-urea breath test (UBT) results with H pylori density and efficacy of eradication therapy in patients with active duodenal ulcers.

METHODS: One hundred and seventeen consecutive outpatients with active duodenal ulcer and H pylori infection were recruited. H pylori density was histologically graded according to the Sydney system. Each patient received lansoprazole (30 mg b.i.d.), clarithromycin (500 mg b.i.d.) and amoxicillin (1 g b.i.d.) for 1 week. According to pre-treatment UBT values, patients were allocated into low ( < 16‰), intermediate (16‰-35‰), and high ( > 35‰) UBT groups.

RESULTS: A significant correlation was found between pre-treatment UBT results and H pylori density (P < 0.001). H pylori eradication rates were 94.9%, 94.4% and 81.6% in the low, intermediate and high UBT groups, respectively (per protocol analysis, P = 0.11). When patients were assigned into two groups (UBT results ≤ 35‰ and > 35‰), the eradication rates were 94.7% and 81.6%, respectively (P = 0.04).

CONCLUSION: The intragastric bacterial load of H pylori can be evaluated by UBT, and high pre-treatment UBT results can predict an adverse outcome of eradication therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori can be identified in 90%-95% of patients with duodenal ulcers and 60%-80% of patients with gastric ulcers[1]. Eradication of H pylori infection was reported to be able to change the natural history of peptic ulcer disease[2-4]. Nowadays, H pylori has been regarded as the main cause of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer[5,6].

Eradication therapy for H pylori has developed rapidly in recent years. The global trend has now shifted to proton pump inhibitor (PPI)– based triple therapy (a PPI and two different antimicrobial agents)[7], which can assure rapid symptom relief, improve ulcer healing, and reduce ulcer recurrence[8,9]. However, treatment failure still occurs in some cases with this advanced PPI-based triple therapy. Patient compliance and antibiotic resistance are currently regarded as the major causes of eradication failure[10]. In addition, several papers have also revealed that high pre-treatment 13C-urea breath test (UBT) results, suggestive of a high intragastric bacterial load, were an independent predictor of treatment failure[10-12]. A high antral density of H pylori may be related to low eradication rate and increased rate of ulcer recurrence[12-14]. The intragastric bacterial load could be another factor affecting the success of eradication therapy.

UBT is the noninvasive method of choice to determine H pylori status. It is easy to perform and reliable, with a high sensitivity and specificity[15]. Furthermore, some authors have found that the results of UBT could be employed to semi-quantitatively assess both the intragastric bacterial load and the severity of gastritis[12,16]. Therefore, we conducted this study to investigate the association of UBT results with H pylori density in the stomach and the efficacy of eradication therapy in patients with active duodenal ulcers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient recruitment

From January 2000 to December 2002, consecutive outpatients with endoscopically verified active duodenal ulcers (5 mm in diameter or larger) at Cathay General Hospital were enrolled for this study. All panendoscopic examinations were performed and interpreted by the same group of experienced endoscopists. We only selected patients with a positive diagnosis of H pylori infection proven by both histological examinations and UBT. To avoid interference in evaluating the status of H pylori, the following patients were initially excluded before endoscopy: those who had ingested bismuth, antibiotics, anti-secretory medication, or PPI during the 4 wk prior to beginning the study; those who used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; those who were pregnant or immuno-compromised; and those who had a history of gastric surgery or a previous attempt to eradicate H pylori. Patients with coexisting gastric ulcers or gastric cancer were also excluded. All procedures were performed after obtaining informed consent from the patients.

The enrolled patients were all treated with the same regimen of 30 mg lansoprazole b.i.d. plus 500 mg clarithromycin b.i.d. and 1 g amoxicillin b.i.d. for the first 7 d and followed by 30 mg lansoprazole once daily for an additional 3 wk. After the completion of such therapy, neither PPI or anti-secretory H2-blocker was used; only oral antacids were taken for symptomatic relief when necessary. The second endoscopic examination was scheduled 4 wk after the completion of therapy. If the patient refused the second endoscopy, we arranged follow-up UBT only.

Histology

During the first endoscopic examination, three biopsies were taken from the gastric antrum (one near the incisura and the other two on the greater and lesser curvature, 2 cm within the pyloric ring)[17]. On the follow-up endoscopic examination, two additional specimens were taken from the greater curvature of the gastric body due to the possibility of patchy distribution of H pylori after eradication therapy. We used an Olympus GIF-XQ 200 endoscope; the biopsy forceps were the FB 25-K type. Specimens were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and with a modified Giemsa stain. Then they were examined by an experienced histopathologist unaware of the patients’ clinical diagnoses for the existence of H pylori. The version of the visual analogue scale in the updated Sydney system was used to grade the density of H pylori (4 grades: normal, no bacteria; mild, focally few bacteria; moderate, more bacteria in several areas; and marked, abundance of bacteria in most glands)[18]. If the density varied, the highest grade of density in the specimens was selected.

Urea breath test (UBT)

UBTs were performed before the start of therapy (right away after the first endoscopy) and on two separate occasions, at 4 and 8 wk after the completion of therapy, respectively. The 13C-urea used was 100 mg of 99% 13C-labelled urea produced by the Institute of Nuclear Energy Research, Taiwan. Patients drank 100 mL of fresh milk as the test meal. The procedure was modified from the European standard protocol for the detection of H pylori[19,20]. We chose 3 per mL for the cut-off level of the rise in the delta value of 13CO2 at 15 min after the ingestion of 13C-urea. UBT was defined as positive when △ δ 13CO2 was above this value. By using this cut-off, the sensitivity and specificity of UBT are 97% and 95%, respectively[20]. According to the pre-treatment UBT value, patients were allocated into low ( < 16‰), intermediate (16 - 35‰), and high ( > 35‰) UBT groups[12].

Eradication of H pylori infection was defined as negative results on both UBT and histology tests at 4 wk after the completion of therapy or negative results on two UBTs at both 4 and 8 wk after the completion of therapy[21].

Statistical analysis

The qualitative data of patients were evaluated using chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. ANOVA test was applied for the quantitative data. The relationship between the UBT results and H pylori density was assessed by Spearman’s rank correlation test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to detect the significant difference in UBT values among patients with different levels of H pylori density. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the eradication rates of H pylori infection in different UBT groups. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

One hundred and twenty-three patients were initially considered eligible for the study, but 6 patients were later excluded due to negative results for H pylori. We thus enrolled 117 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria (intention-to-treat). Among them, 4 patients did not complete the study adequately because of not taking drugs regularly (2 cases) or taking disallowed medications (two cases) . Therefore, a total of 113 patients were included for the per protocol analysis. Table 1 shows the demographic and other baseline characteristics of the patients according to the levels of UBT results. None of the differences in variables was statistically significant.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients

|

UBT result (‰) |

|||

| Low (< 16) n = 39 | Intermediate (16-35) n = 36 | High (> 35) n = 38 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 24 | 26 | 23 |

| Female | 15 | 10 | 15 |

| Age (year) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 45.1 ± 10.6 | 44.6 ± 12.8 | 47.0 ± 13.2 |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 20 | 20 | 22 |

| No | 19 | 16 | 16 |

| Ulcer size | |||

| < 1 cm | 35 | 32 | 34 |

| 1-2 cm | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| > 2 cm | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| No. of ulcers | |||

| One | 37 | 33 | 35 |

| Two | 2 | 3 | 3 |

Correlation between H pylori density and UBT results

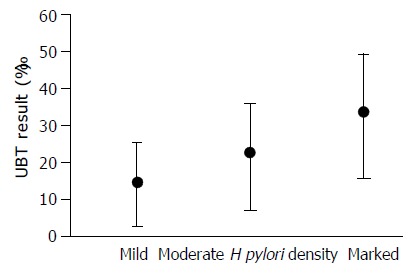

Levels of H pylori density, as assessed histologically, were compared with the UBT results in Figure 1. The median (P75 - P25) UBT value in each group was 9.6 (13.2), 17.9 (26.9) and 33.2 (25.4), respectively (P < 0.001). A significant correlation was found between the UBT result and H pylori density (rs = 0.47).

Figure 1.

Relationship between UBT result and Helicobacter pylori density. P < 0.001.

Eradication rates of H pylori infection and UBT results

The overall eradication rates were 87.2% (95%CI: 79.5%-92.4%) in the intention-to-treat analysis and 90.3% (95%CI: 82.9%-94.8%) in the per protocol analysis. Table 2 shows the eradication rates in the three UBT groups. Although there was a downward trend in the eradication rate with an increase in the UBT results, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.11). However, when the UBT results were allocated into only two groups ( ≤ 35‰ and > 35‰), the difference in the eradication rates between the 2 groups became statistically significant (P = 0.04) (Table 2). The higher UBT group had less eradication efficacy.

Table 2.

Correlation between UBT results and eradication rates of H pylori infection

| UBT result (‰) | Eradication rate (95%CI) |

| Low (< 16) n = 39 | 94.9 (81.4%-99.1%) |

| Intermediate (16-35) n = 36 | 94.4 (79.9%-99.0%) |

| Low + Intermediate (n = 75) | 94.7 (86.2%-98.3%) |

| High ( > 35) n = 38 | 81.6 (65.1%-91.7%)12 |

, comparison among low, intermediate and high UBT groups (three groups); P = 0.11;

, comparison between low + intermediate and high UBT groups (two groups), P = 0.04.

DISCUSSION

H pylori is now known to play the leading role in the pathogenesis of duodenal ulcer. Many reports have shown that eradication of H pylori not only aids ulcer healing but also prevents ulcer recurrence[22]. Eradication of H pylori can cure duodenal ulcer disease, and has become a standard therapy for duodenal ulcer patients[2,3,13].

The short-term (7 d) triple therapies including a PPI and two antibiotics (clarithromycin, and amoxicillin or a nitroimidazole compound) are currently considered as the firstline anti-H pylori regimens[7]. Despite the high efficacy, treatment failure occurs in a proportion of patients, varying from 10% to 25%, in the first attempt to eradicate H pylori[10]. Patient compliance and antibiotic resistance are regarded as the key factors affecting the outcome of treatment[10,12]. However, several reports have also revealed that patients with higher intragastric H pylori loads had reduced eradication rates. This association was found in both bismuth- and PPI-based triple therapies[10,12-14]. Thus, pre-treatment bacterial density has been used by some authors to predict the success of H pylori eradication in patients with duodenal ulcers[13,14,23]. The relationship between the eradication efficacy and intragastric bacterial load supports the importance of bacterial density as a factor in the treatment of H pylori infection[10,12-14].

UBT is the most useful noninvasive test for H pylori. The bacterium produces a powerful urease, which is the basis of UBT[24]. Since the numerical results of UBT are a function of the total urease activity within the stomach, they might be a quantitative index of the density of gastric H pylori colonization. Many studies have reported inconsistent conclusions about the relationship between the UBT results and those of histology-based semi-quantitative measures of bacterial infection. Such inconsistencies may have arisen from inter-observer differences or inaccuracies in the estimation of bacterial density[25]. Thus, UBT is best considered a qualitative test by some authors’ opinions[15]. However, in a recent study, Kobayashi et al[26] used a sensitive real-time (TaqMan) polymerase chain reaction to estimate numbers of H pylori genomes in biopsy samples, and found that the numerical results of H pylori density correlated significantly with the values of UBT. So, they concluded the information from UBT was useful not only in identifying H pylori infection but also in indirectly assessing of the numbers of H pylori in the stomach. In our study, UBT results correlated with the density of H pylori in the stomach as well, although the number of cases was relatively small.

Higher intragastric bacterial loads, as semi-quantitatively assessed by UBT, are associated with lower eradication rats[12-14]. Adopting the same cut-off value of δ UBT used by Perri et al[12], that is, > 35‰ as an index of a high H pylori load, we confirmed the existence of an inverse relationship between successful eradication and intragastric bacterial load. Although we did not find a correlation between eradication efficacy and the UBT results when we allocated the patients into three UBT groups, statistically significant correlation was revealed when patients’ UBT results were divided at 35‰ into 2 groups.

High UBT values may reflect high urease activity and indicate a high intragastric bacterial load. As observed in other infectious diseases, the bacterial load could be important in determining the outcome of eradication treatment[11]. There are other factors than the number of H pylori which influence the UBT results, including gastric emptying time, area of contact between the bacteria and the urea in the stomach, and differences in urease activity among H pylori strains[15]. Levels of H pylori too low to be detected by histology are usually associated with a negative UBT. High urease activity implies a high density of H pylori. Between the two extremes, some authors have considered that the actual test results can tell the clinicians little except that the infection is present[15]. When we wanted to use the results of UBT as a predictor of the efficacy of eradication therapy of H pylori infection, we had to set a high cut-off level to obtain statistical significance. Our result is consistent with previous reports which also revealed that high pre-treatment UBT results could be an independent predictor of eradication failure[10-12].

Recognition of predictors for eradication therapy is helpful in clinical practice. Since high UBT results adversely influence the efficacy of eradication therapy, patients with high intragastric bacterial loads may benefit from an extension of treatment duration from 1 to 2 wk[10]. Prolonging the duration of the standard triple therapy has been proposed to overcome the unfavorable effect caused by high H pylori density and proven to be effective[10,12].

Most patients (113/117 cases, 96.6%) in this study had good drug compliance. However, bacterial culture and drug sensitivity test to assess the effect of antibiotic resistance were not performed. Thus, we cannot demonstrate the influence of drug resistance on eradication therapy. The culturing and susceptibility testing of H pylori are time-consuming, and they are not performed routinely in most countries[27]. Our study may therefore provide an easy and practical option to disclose the pre-treatment predictor of eradication therapy when information on drug sensitivity is not available.

In conclusion, our findings reveal that the UBT results correlate with H pylori density in the stomach, and that high pre-treatment UBT results might adversely affect the success of eradication therapy in patients with active duodenal ulcers. Identifying patients with high bacterial loads before treatment and thus making adjustment in therapeutic regimens may further improve the efficacy of eradication therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Mr. Shui-Cheng Lee (Institute of Nuclear Energy Research, Taiwan) for his help in the assessment of the urea breath test. This research was supported by a grant from Cathay General Hospital, Taiwan.

Footnotes

Edited by Xia HHX and Xu FM

References

- 1.Hunt RH. Peptic ulcer disease: defining the treatment strategies in the era of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:36S–40S; discussion 40S-43S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss S, Calam J. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcers: the present position. Gut. 1992;33:289–292. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt RH. pH and Hp--gastric acid secretion and Helicobacter pylori: implications for ulcer healing and eradication of the organism. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:481–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham DY, Lew GM, Klein PD, Evans DG, Evans DJ, Saeed ZA, Malaty HM. Effect of treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection on the long-term recurrence of gastric or duodenal ulcer. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:705–708. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-9-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vandenplas Y. Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:20–31. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wewer V, Andersen LP, Paerregaard A, Gernow A, Hansen JP, Matzen P, Krasilnikoff PA. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori in children with recurrent abdominal pain. Helicobacter. 2001;6:244–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2001.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asaka M, Sugiyama T, Kato M, Satoh K, Kuwayama H, Fukuda Y, Fujioka T, Takemoto T, Kimura K, Shimoyama T, et al. A multicenter, double-blind study on triple therapy with lansoprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in Japanese peptic ulcer patients. Helicobacter. 2001;6:254–261. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2001.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penston JG. Review article: Helicobacter pylori eradication--understandable caution but no excuse for inertia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:369–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Logan RP, Bardhan KD, Celestin LR, Theodossi A, Palmer KR, Reed PI, Baron JH, Misiewicz JJ. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and prevention of recurrence of duodenal ulcer: a randomized, double-blind, multi-centre trial of omeprazole with or without clarithromycin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:417–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maconi G, Parente F, Russo A, Vago L, Imbesi V, Bianchi Porro G. Do some patients with Helicobacter pylori infection benefit from an extension to 2 weeks of a proton pump inhibitor-based triple eradication therapy? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:359–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perri F, Villani MR, Festa V, Quitadamo M, Andriulli A. Predictors of failure of Helicobacter pylori eradication with the standard 'Maastricht triple therapy'. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1023–1029. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perri F, Clemente R, Festa V, Quitadamo M, Conoscitore P, Niro G, Ghoos Y, Rutgeerts P, Andriulli A. Relationship between the results of pre-treatment urea breath test and efficacy of eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;30:146–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheu BS, Yang HB, Su IJ, Shiesh SC, Chi CH, Lin XZ. Bacterial density of Helicobacter pylori predicts the success of triple therapy in bleeding duodenal ulcer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:683–688. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moshkowitz M, Konikoff FM, Peled Y, Santo M, Hallak A, Bujanover Y, Tiomny E, Gilat T. High Helicobacter pylori numbers are associated with low eradication rate after triple therapy. Gut. 1995;36:845–847. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.6.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham DY, Klein PD. Accurate diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori. 13C-urea breath test. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000;29:885–93, x. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Labenz J, Bärsch G, Peitz U, Aygen S, Hennemann O, Tillenburg B, Becker T, Stolte M. Validity of a novel biopsy urease test (HUT) and a simplified 13C-urea breath test for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection and estimation of the severity of gastritis. Digestion. 1996;57:391–397. doi: 10.1159/000201366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genta RM, Graham DY. Comparison of biopsy sites for the histopathologic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: a topographic study of H. pylori density and distribution. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:342–345. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–1181. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Logan RP, Polson RJ, Misiewicz JJ, Rao G, Karim NQ, Newell D, Johnson P, Wadsworth J, Walker MM, Baron JH. Simplified single sample 13Carbon urea breath test for Helicobacter pylori: comparison with histology, culture, and ELISA serology. Gut. 1991;32:1461–1464. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.12.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang WM, Lee SC, Ding HJ, Jan CM, Chen LT, Wu DC, Liu CS, Peng CF, Chen YW, Huang YF, et al. Quantification of Helicobacter pylori infection: Simple and rapid 13C-urea breath test in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:330–335. doi: 10.1007/s005350050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unge P. The OAC and OMC options. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11 Suppl 2:S9–17; discussion S23-4. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199908002-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosking SW, Ling TK, Chung SC, Yung MY, Cheng AF, Sung JJ, Li AK. Duodenal ulcer healing by eradication of Helicobacter pylori without anti-acid treatment: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1994;343:508–510. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai YC, Wang TH, Huang SH, Yang SS, Wu CH, Chen TK, Lee CL. Density of Helicobacter pylori may affect the efficacy of eradication therapy and ulcer healing in patients with active duodenal ulcers. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1537–1540. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i7.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atherton JC, Spiller RC. The urea breath test for Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1994;35:723–725. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.6.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.el-Zimaity HM, Graham DY, al-Assi MT, Malaty H, Karttunen TJ, Graham DP, Huberman RM, Genta RM. Interobserver variation in the histopathological assessment of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi D, Eishi Y, Ohkusa T, Ishige T, Minami J, Yamada T, Takizawa T, Koike M. Gastric mucosal density of Helicobacter pylori estimated by real-time PCR compared with results of urea breath test and histological grading. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:305–311. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-4-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam SK, Talley NJ. Report of the 1997 Asia Pacific Consensus Conference on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]