Abstract

Objective

A systematic literature review (SLR; 2009–2014) to compare a target-oriented approach with routine management in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) to allow an update of the treat-to-target recommendations.

Methods

Two SLRs focused on clinical trials employing a treatment approach targeting a specific clinical outcome were performed. In addition to testing clinical, functional and/or structural changes as endpoints, comorbidities, cardiovascular risk, work productivity and education as well as patient self-assessment were investigated. The searches covered MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane databases and Clinicaltrial.gov for the period between 2009 and 2012 and separately for the period of 2012 to May of 2014.

Results

Of 8442 citations retrieved in the two SLRs, 176 articles underwent full-text review. According to predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria, six articles were included of which five showed superiority of a targeted treatment approach aiming at least at low-disease activity versus routine care; in addition, publications providing supportive evidence were also incorporated that aside from expanding the evidence provided by the above six publications allowed concluding that a target-oriented approach leads to less comorbidities and cardiovascular risk and better work productivity than conventional care.

Conclusions

The current study expands the evidence that targeting low-disease activity or remission in the management of RA conveys better outcomes than routine care.

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Treatment, Disease Activity

Introduction

New treatment options and new treatment strategies have changed the achievable outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) over the last 20 years.1–5 The treat-to-target (T2T) algorithm developed in 2010 consisted of 10 recommendations advocating the implementation of therapeutic principles, especially targeting remission or low-disease activity by adjusting therapy in the context of regular disease activity assessments. These recommendations were based on evidence obtained from a systematic literature review (SLR),6 but to a large extent also on expert opinion. The international task force of the T2T project assumed that the evidence base for the T2T recommendations may have expanded and further developed and that an update was needed especially to learn whether the expert-based statements were supported or contested by new evidence. Moreover, it was deemed interesting and important by the steering committee to not only focus on the traditional clinical, functional and structural endpoint but also on additional aspects related to quality of life and other outcomes important to patients.

Methods

In 2012 and 2014, systematic literature searches of available evidence regarding the effects of treating RA strategically were conducted. In addition to testing clinical, functional and/or structural changes as endpoints, comorbidities, cardiovascular (CV) risk, work productivity and education as well as patient self-assessment were investigated. In the opinion of the steering committee, an initial search of the 2009–2012 literature performed in 2012 did not provide sufficient new evidence to justify an amendment of the recommendations. A new search on the literature published between 2012 and 5/2014 was now performed; that latter SLR focuses also on the additional outcomes mentioned above.

SLR: update

The new SLRs are a follow-up to the SLR performed by Schoels et al in 2009.6 The search strategy developed then by the international steering committee of the T2T project and described in detail elsewhere6 was expanded by using additional keywords (see below). Two research fellows (MMS in 2012; MAS in 2014) performed the SLRs with support from their mentors.

The definitions of the 2009 SLR were generally also used for this update (with slight changes). These were:

Strategy trial—clinical trial of any RA drug treatment, in which a clear outcome target was the primary endpoint and therapeutic consequences of failing to reach the target were predefined.

Targets—a target could be formulated by clinical, serological, patient reported, functional or imaging-derived variables; individual measures (eg, joint counts or acute phase reactants), composite scores (eg, disease activity score (DAS) or simplified disease activity index (SDAI)), response criteria (eg, those defined by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) or the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)), structural or ultrasound outcomes were considered alike.

Outcomes—clinical, functional, serological, structural changes and comorbidity, as defined in the respective trials, were compared between treatment groups.6

Beyond those applied in 2009, several new keywords: “patient-self assessment”, “comorbidities”, “cardiovascular risk”, “work productivity” and “education” in a target-oriented study were used. Controlled trials and observational studies were included. The searches covered the databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane and Clinicaltrial.gov for the period between 1/2009 and 5/2014. The PICOs (see online supplementary table S1) and the search strings are shown in the online supplementary material (see online supplementary table S2 for 2012, supplementary table S3 for 2014). Like in the previous work, the search was limited to human RA, adults and the English language. Furthermore, we did not exclude studies based on quality in the initial searches.

Results

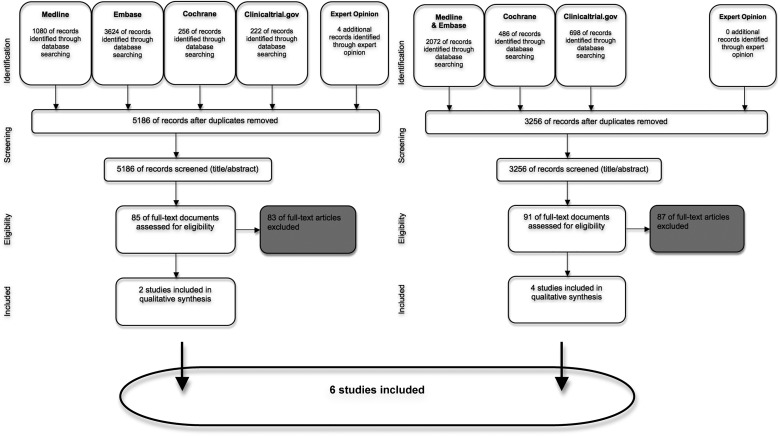

The first search performed in 2012 yielded 3256 hits. The search performed in 2014 arrived at 5186 records for further investigation (figure 1). Title and abstract review according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria led to assessment of eligibility of 91 and 85 full-text documents, respectively. The detailed review of the records in relation to the primary search objectives (comparison of primary endpoints in a priori strategy trials) resulted in the inclusion of four papers7–10 from the search in 2012 and two additional papers11 12 from the search performed in 2014. An overview of the six included studies is given in table 1A. From the identified references, we extracted information about the targets driving treatment decisions, the interval of control examinations, the numbers of patients included and the outcomes (table 1A).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the systematic literature search. Diagrammed are the results of the initial and second search (2012 and 2014, respectively) and the selection process of abstract screening, full-text review and inclusion according to expert opinion.

Table 1.

(A) Publications comparing an a priori targeted treatment strategy with routine care; (B) supportive evidence

| (A) Studies directly addressing outcomes based on different treatment strategies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Groups | Treatment decision driving target | Interval of control examinations | N | Outcomes | Randomisation |

| Goekoop-Ruiterman et al7 | Targeted group (T) | DAS≤2.4 | 3 months | 234 | Clinical outcome at 1 year Primary outcome: change damage progression by the total SHS | Yes |

| Routine control group (R) | Treatment changes left to the discretion of the treating doctor | 3 months | 201 | |||

| Soubrier et al (GUEPARD/ESPOIR)8 | GUEPARD—Targeted group (T) | LDA by DAS28ESR<3.2 | 3 months | 65 | Assessed variables: SJ, TJ, VAS pain, VAS general wellbeing, VAS physician overall assessment, morning stiffness, ESR, CRP, HAQ, radiographs hands and feet (SHS) | No |

| ESPOIR—Routine control group (R) | Assessment at weeks 0, 24 and 52 | 130 | ||||

| Van Eijk et al (STREAM)9 | Targeted group (T) | DAS(44-joint score)<1.6 | 3 months | 42 | Clinical outcome at 2 years Primary endpoint: progression of radiographic joint damage at 2 years Secondary endpoints: difference between the two treatment strategies after 2 years regarding DAS, the percentage of patients in clinical remission (DAS<1.6), HAQ and adverse events | Yes |

| Routine control group (R) | Treatment according to rheumatologist´s preference | 3 months | 40 | |||

| Schipper et al(DREAM)10 | Targeted group (T) | DAS 28<2.6 | Assessment at weeks 0, 8, 12, 20, 24, 36 | 126 | Clinical outcome at 1 year Primary endpoint: percentage of patients in remission (DAS28<2.6) Secondary endpoint: time to achieve remission, the course over time of the DAS28, the percentage of patients with “low” disease activity (DAS28≤3.2), the mean change in DAS28 and individual core set variables from baseline to 1 year | No |

| Routine control group (R) | Treatment at the discretion of the treating rheumatologist | Assessment at weeks 0, 12, 24, 36, 52 | 126 | |||

| Pope et al11 | DAS—targeted group (T) | DAS28<2.6 | Patients could be seen at any time as per judgement of the treating physician. Recommended visits were at 0, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 18 months | 100 | Clinical outcome at 1 year Primary endpoint: change in DAS 28 Secondary endpoint: changes at 6, 12, and 18 months in the SJC, TJC, CRP, ESR, HAQ, PGL, WLQ, patient satisfaction (5-point Likert scale), achievement of LDA (DAS<3.2), disease remission (DAS<2.6), and good/moderate EULAR response and time to achieve these end points | Cluster randomised |

| 0-SJC—targeted group (T) | 0-SJC | Patients could be seen at any time as per judgement of the treating physician. Recommended visits were at 0, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 18 months | 99 | |||

| Routine control group (R) | Treatment left at the discretion of the treating physician | Patients could be seen at any time as per judgement of the treating physician. Recommended visits were at 0, 6, 12, 18 months | 109 | |||

| Vermeer et al (DREAM)12 | Targeted group (T) | DAS28<2.6 | 0, 8, 12, 20, 24, 36, 52 weeks | 261 | The ICER per patient in remission and ICUR per QALY were calculated over two and 3 years of follow-up | No |

| Routine control group (R) | Treatment left at the discretion of the rheumatologist | 3 Months | 213 | |||

| Panel (B) Supportive evidence for differences of outcomes depending on reaching different endpoints | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Patients | Target/outcome | Conclusion | Randomisation |

| Targeting cardiovascular risk | ||||

| Crowson et al24 | Review | n.a. | Suppression inflammation—may also reduce risk of heart disease; investigations of the innate and adaptive immune responses occurring in RA may delineate novel mechanisms in the pathogenesis of heart disease and help identify novel therapeutic targets for the prevention and treatment of heart disease Therapies used to treat RA may also affect the development of heart diseases, by suppressing inflammation, they may also reduce the risk of heart disease. Therapies used to treat RA may also affect the development of heart diseases, by suppressing inflammation, they may also reduce the risk of heart disease |

Review |

| Work/productivity | ||||

| Rantalaiho et al20 | 195 | Strict remission rates at 6, 12 and 24 months as well as the cumulative work disability days up to 5 years in these four subgroups | Using targeted treatment with monotherapy may well substitute for using combination DMARDs, but to benefit as many early RA patients as possible both approaches are necessary. Targeted treatment strategy is beneficial irrespective of the type of therapy | Yes |

| Smolen et al21 | 834 enrolled—604 eligible for double-blind period | Sustained LDA | Conventional or reduced doses of etanercept with MTX in patients with moderately active RA more effectively maintain LDA than does MTX alone after withdrawal of etanercept | Yes |

| Radner et al19 | 356 | Physical function, health-related quality of life, work productivity, estimation of direct and indirect costs | Patient with remission show better function, health-related quality and productivity, even when compared with another good state, such as LDA. Also from a cost perspective, remission appears superior to all other states | No |

| Education | ||||

| Pope et al25 | 1000 serial RA charts | SDAI | Small group learning with feedback from practice audits is an inexpensive way to improve outcomes in RA | Cluster randomised |

| Additional evidence | ||||

| Thiele et al28 | 6864 | DAS28 (Boolean/SDAI) | Patients fulfilling the new remission criteria tend to be not only free from active RA, but also from other disabling diseases. If these criteria are applied in clinical practice to guide treatment decisions, the impact of comorbidity should be taken into account | No |

| Vermeer et al29 | 409 | DAS28, HAQ, SF36, MCS, SHS | In very early RA, T2T leads to high (sustained) remission rates, improved physical function and health-related quality of life, and limited radiographic damage after 3 years in daily clinical practice | No |

| Sakellariou et al30 | 166 | SDAI, DAS28, HAQ, PDPS | The new remission definitions confirmed their validity in an observational setting and identify patients with better disease control. | No |

| Balsa et al31 | 97 | SDAI | The results suggest that the SDAI classification of remission is closer to the concept of an absence of inflammatory activity, as defined by the absence of positive PD signal by US | No |

| Dale et al32 | 111 | DAS44, HAQ, MRI (RAMRIS), X-ray hands + feet | MSUS disease activity assessment was not associated with improved clinical outcomes except a higher rate of DAS44 remission after 18 months. Target US sonographic remission does not appear to be superior to clinical LDA |

Yes |

| Dale et al33 | 53 | DAS28 | Compared to the DAS28, global RA disease activity assessment using a limited MSUS joint set provided additional disease activity information and led to altered treatment decisions in a significant minority of occasions. This may allow further tailoring of DMARD therapy by supporting DMARD escalation in patients with continuing subclinical synovitis and preventing escalation in symptomatic patients with minimal clinical and/or ultrasonographic synovitis | No |

CRP, C reactive protein; DAS, disease activity score; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; DREAM, Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring; ESPOIR, Etude et Suivi des Polyarthrites Indifférenciées Récentes; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GUEPARD, Guérir la Polyarthrite Rhumatoide Débutante; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; ICUR, incremental cost utility ratio; LDA, low-disease activity; MCS, mental component summary; MSUS, musculoskeletal ultrasound; MTX, methotrexate; PDPS, power Doppler-positive synovitis; PD, power Doppler; PGL, patient global assessment of disease activity; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RAMRIS, rheumatoid arthritis MRI joint space narrowing score; SDAI, simplified disease activity index; SF36, short form 36 physical component summary; SHS, Sharp/van der Heijde radiographic score; SJ, swollen joint; SJC, swollen joint count; STREAM, Strategies in Early Arthritis Management TJ, tender joint; TJC, tender joint count; T2T, treat to target; US, ultrasound; VAS, visual analogue scale; WLQ, work limitations questionnaire.

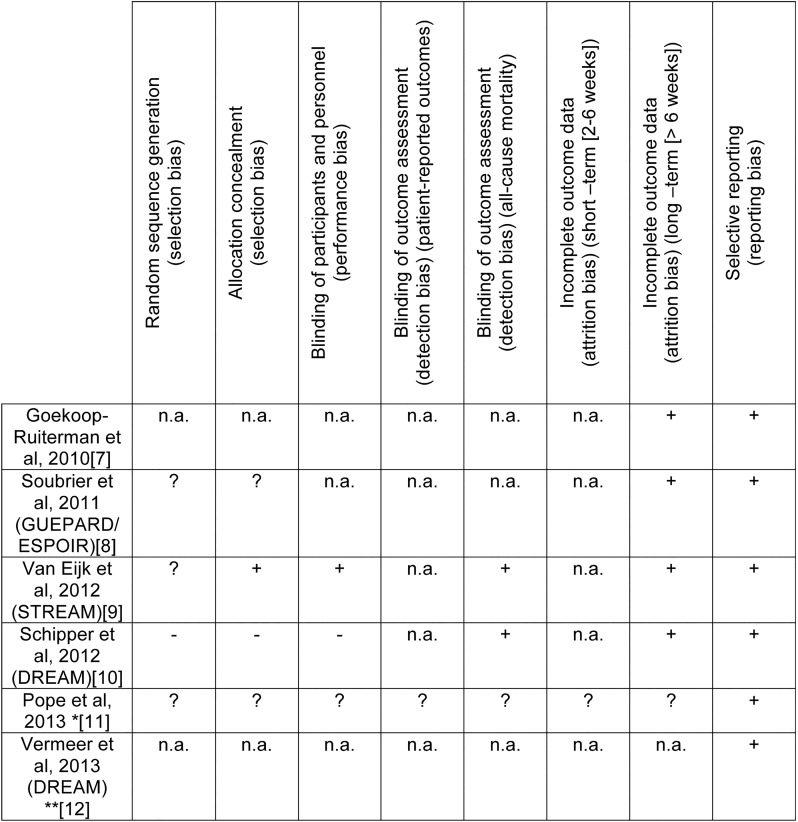

Five of the six included studies dealt with early RA7–10 12 and one trial with established RA.11 All studies showed a superiority of a T2T strategy compared with routine care (RC)7 8 10–12 except for one study (Strategic Reperfusion Early After Myocardial Infarction).9 For the included studies, the risk of bias was assessed according to the scheme proposed by the ‘Cochrane risk of bias assessment’ (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Rick of bias summary figure. +Low risk of bias, −High risk of bias, ?Unclear risk of bias, n.a. Not applicable. *In the study of Pope et al physicians were randomised. **Vermeer et al was comparing real life data from cohorts.

In early RA, the T2T strategy brought more patients into remission or low-disease activity and this was achieved more rapidly. Also, patients in the T2T group experienced larger improvements in patient assessments of pain, functional ability and disease activity (Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring (DREAM)).10 In one trial of recent-onset active RA, the tight control approach showed that more patients achieved remission without disability and radiographic progression (Guérir la Polyarthrite Rhumatoide Débutante (GUEPARD)/Etude et Suivi des Polyarthrites Indifférenciées Récentes (ESPOIR)).8 Another study showed similar findings: the DAS-driven treatment led to better clinical outcomes (health assessment questionnaire, DAS28 and median erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and numerically, but not statistically different suppression of joint damage in the T2T group.7

In a study dealing with established active RA,11 physicians were randomised into three groups (treating according to RC or targeting a DAS28<2.6 or a swollen joint count of 0). Although there was no difference in terms of therapeutic endpoint achievement, the time to reach a good/moderate EULAR response was significantly shorter and the dropout rates were significantly lower when using the targeted approaches.11 Furthermore, using real-life data from the DREAM registry and the Nijmegen early RA inception cohort, a T2T strategy was found to be cost-effective compared with RC.12

Only one study did not show superior effects of a T2T strategy; however, this study assessed only a small number of patients with low radiographic damage and presented good functional status in both treatment groups.9 Further studies are discussed in some more detail in the online supplement S4.

Regarding comorbidities, CV risk, work productivity or the role of (patient) education, none of the studies comparing T2T to RC had any of these outcomes as primary endpoint. However, these outcomes were addressed in observational data or registry studies comparing different strategic treatment approaches and endpoints, and therefore, these publications were regarded as further supporting evidence and are presented in table 1B.

Subanalysis of PREMIER (a multicenter, randomised, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment) and Active-Controlled Study of Patients Receiving Infliximab for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis of Early Onset (ASPIRE) data showed that the level of disease activity, the duration of SDAI remission and latency to remission all affect radiographic progression.13 There is a direct relationship between disease activity and radiographic changes but a dissociation of the effect with tumour necrosis factor inhibitor use.14 Among these publications were studies showing that Clinical Activity Disease Index remission is associated with lower CV risk and improved CV outcomes,15 16 and the absence of swollen joints with improved overall survival.17

Additional studies that emerged during the SLR were categorised by topics and also presented to the task force. All these studies are listed in the online material (see online supplementary table S5).

Aside from the work of Pope et al,11 all of the above-described articles studied patients with early RA. However, Gullick et al18 investigated an observational cohort of patients with long-standing RA in a setting of usual care. In their study, the authors compared the outcomes of an RA centre routinely using goal-directed therapy aimed at DAS28<2.6 with an age-matched and sex-matched sample of consecutive patients from other RA clinics. Significantly more T2T patients achieved the target, irrespective of their disease duration, and T2T led to significantly improved functional outcomes compared with RC.

Discussion

Since the original search informing the T2T task force, six new studies have been published, five of which fully support that a treatment strategy using a defined target conveys superior clinical, functional and structural outcomes compared with RC. In contrast to the data available in 2010, now more studies have used clinical remission defined by DAS or DAS28 as a main endpoint, which is a more stringent target than low-disease activity. While trials directly comparing potential differences in targeting remission versus low-disease activity are not available, supportive evidence exists that reaching ACR–EULAR remission is superior in terms of physical function, quality of life and work productivity and significant differences ensue when moving from one of these desired states to the other.19

In 2010, studies evaluating target-steered versus non-steered treatment approaches were only available for early RA. The new search revealed additional investigations on early or even recent-onset RA, but also data on established RA. Indeed, information on target steered therapy in established RA was a point in the research agenda in 2010; the data reveal that also in long-standing RA a T2T strategy is superior to RC.11 18

Finally, some new aspects were evaluated here, namely work productivity, comorbidities and effect of education on treatment outcomes. While trials comparing different therapeutic strategies using these outcomes as primary endpoints are not yet available, secondary analyses reveal that lower disease activity is associated with better work productivity, less comorbidity and CV risk and that better education is likewise related to better clinical outcomes.11 15 16 19–25 The task force was informed about these data as supportive evidence.

The present SLR provided new evidence regarding several items of the 2010 T2T recommendations,26 which allowed to update the recommendations as presented in the paper by Smolen et al.27 Indeed, the evidence base of several items increased from D to B or A (for details, see main paper) and several items, such as the overarching principle B and points 1 and 3 (with respect to established RA), as well as point 7, could be amended or expanded based on this new SLR. In conclusion, new and expanded evidence has been identified confirming that treating RA to a target of low-disease activity or remission enables patients to reach better outcomes than when they are exposed to RC. This information was provided to and discussed in detail by the task force allowing to develop an update of the T2T recommendations with much higher levels of evidence.27

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MAS and MMS are joint first author. Conception and design: MAS, MMS, JSS, DA, FCB, GB, VB, MD, PE, BH, JG-R, TKK, PN, VN-C, MS-V, RvV, DvdH, TAS. Analysis and interpretation of data: MAS, MMS, JSS, TAS, with all authors involved in the revision and final phases. Drafting the article and revising it critically for content: MAS, MMS, JSS, TAS, with all authors involved in the revision and final phases. Approval of the final version to be published: all authors were involved.

Funding: This study was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AbbVie. AbbVie had no influence on the selection of papers, extraction of data or writing of this manuscript.

Competing interests: MAS has received speaker fees from MSD, none of them relates to this work. JSS has provided expert advice to AbbVie, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Astro, BMS, Celgene, Glaxo, Janssen, Novartis-Sandoz, Novo-Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung, Sanofi and UCB. DA has provided expert advice to AbbVie, Astra-Zeneca, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novo-Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB. GB has provided expert advice to AbbVie, BMS, MSD/Merck, Novartis/Sandoz, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. VB has unrestricted grants or consulting agreements with Abbvie, Amgen, BMS, Roche, Medexus, Pfizer, Crescendo, UCB, Janssen, Regeneron. MD has received honorarium fees for participation at symposia and/or advisory boards organised by PFIZER, ABBVIE, UCB, MERCK, NOVARTIS, LILLY. His department has received research grants to conduct studies from PFIZER, ABBVIE, UCB, MERCK, NOVARTIS, LILLY. PE has received consulting fees from Abbvie, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, Lilly, Novartis and grant/research support from Abbvie, Merck, Pfizer, Roche. BH has received speaker fees from Abbvie, Amgen, BMS, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche and UCB but none in relation with this work. JG-R has received speaker fees from AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Glaxo, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB, and provided expert advice to AbbVie, BMS, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi and UCB. TKK has provided expert advice to AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Hospira, Merck Serono, MSD, Novartis, Orion Pharma, Pfizer, Roche, UCB. PN received research grants for clinical trials and honoraria for advice and lectures on behalf of all pharma making targeted biological therapies. VN-C has received speaker fees from AbbVie, BMS and MSD, none of them relates to this work. RvV received research support and grants from AbbVie, BMS, GSK, Pfizer, Roche, UCB and consultancy honoraria from AbbVie, Biotest, BMS, Crescendo, GSK, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, UCB, Vertex. DvdH has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Augurex, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Centocor, Chugai, Covagen, Daiichi, Eli-Lilly, Galapagos, GSK, Janssen Biologics, Merck, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, UCB, Vertex and is Director of Imaging Rheumatology bv. TAS has received speaker fees from UCB, AbbVie and MSD, none of them relates to this work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.van der Heijde DM, van ‘t Hof M, van Riel PL, et al. Development of a disease activity score based on judgment in clinical practice by rheumatologists. J Rheumatol 1993;20:579–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevoo ML, van ‘t Hof MA, Kuper HH, et al. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:44–8. 10.1002/art.1780380107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Schiff MH, et al. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology 2003;42:244–57. 10.1093/rheumatology/keg072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:727–35. 10.1002/art.1780380602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aletaha D, Nell VP, Stamm T, et al. Acute phase reactants add little to composite disease activity indices for rheumatoid arthritis: validation of a clinical activity score. Arthritis Res Ther 2005;7:R796–806. 10.1186/ar1740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoels M, Knevel R, Aletaha D, et al. Evidence for treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: results of a systematic literature search. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:638–43. 10.1136/ard.2009.123976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Kerstens PJ, et al. DAS-driven therapy versus routine care in patients with recent-onset active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:65–9. 10.1136/ard.2008.097683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soubrier M, Lukas C, Sibilia J, et al. Disease activity score-driven therapy versus routine care in patients with recent-onset active rheumatoid arthritis: data from the GUEPARD trial and ESPOIR cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:611–15. 10.1136/ard.2010.137695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Eijk IC, Nielen MM, van der Horst-Bruinsma I, et al. Aggressive therapy in patients with early arthritis results in similar outcome compared with conventional care: the STREAM randomized trial. Rheumatology 2012;51:686–94. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schipper LG, Vermeer M, Kuper HH, et al. A tight control treatment strategy aiming for remission in early rheumatoid arthritis is more effective than usual care treatment in daily clinical practice: a study of two cohorts in the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:845–50. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pope JE, Haraoui B, Rampakakis E, et al. Treating to a target in established active rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor: results from a real-world cluster-randomized adalimumab trial. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:1401–9. 10.1002/acr.22010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vermeer M, Kievit W, Kuper HH, et al. Treating to the target of remission in early rheumatoid arthritis is cost-effective: results of the DREAM registry. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:350 10.1186/1471-2474-14-350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aletaha D, Funovits J, Breedveld FC, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis joint progression in sustained remission is determined by disease activity levels preceding the period of radiographic assessment. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:1242–9. 10.1002/art.24433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smolen JS, Han C, van der Heijde DM, et al. Radiographic changes in rheumatoid arthritis patients attaining different disease activity states with methotrexate monotherapy and infliximab plus methotrexate: the impacts of remission and tumour necrosis factor blockade. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:823–7. 10.1136/ard.2008.090019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Provan SA, Semb AG, Hisdal J, et al. Remission is the goal for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional comparative study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:812–17. 10.1136/ard.2010.141523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solomon DH, Kremer J, Curtis JR, et al. Explaining the cardiovascular risk associated with rheumatoid arthritis: traditional risk factors versus markers of rheumatoid arthritis severity. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1920–5. 10.1136/ard.2009.122226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sciré CA, Lunt M, Marshall T, et al. Early and sustained remission is associated with improved survival in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis: Results from the norfolk arthritis register. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;71:95–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-eular.1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gullick NJ, Oakley SP, Zain A, et al. Goal-directed therapy for RA in routine practice is associated with improved function in patients with disease duration up to 15 years. Rheumatology 2012;51:759–61. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radner H, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: benefit over low disease activity in patient-reported outcomes and costs. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:R56 10.1186/ar4491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rantalaiho V, Kautiainen H, Korpela M, et al. Physicians’ adherence to tight control treatment strategy and combination DMARD therapy are additively important for reaching remission and maintaining working ability in early rheumatoid arthritis: a subanalysis of the FIN-RACo trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:788–90. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smolen JS, Nash P, Durez P, et al. Maintenance, reduction, or withdrawal of etanercept after treatment with etanercept and methotrexate in patients with moderate rheumatoid arthritis (PRESERVE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:918–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61811-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dirven L, van den Broek M, van Groenendael JH, et al. Prevalence of vertebral fractures in a disease activity steered cohort of patients with early active rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:125 10.1186/1471-2474-13-125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnan E, Lingala B, Bruce B, et al. Disability in rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biological treatments. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:213–18. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crowson CS, Liao KP, Davis JM III, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J 2013;166:622–8 e621 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pope J, Thorne C, Cividino A, et al. Effect of rheumatologist education on systematic measurements and treatment decisions in rheumatoid arthritis: the metrix study. J Rheumatol 2012;39:2247–52. 10.3899/jrheum.120597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:631–7. 10.1136/ard.2009.123919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2015. Published Online First 12 May 2015. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiele K, Huscher D, Bischoff S, et al. Performance of the 2011 ACR/EULAR preliminary remission criteria compared with DAS28 remission in unselected patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1194–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vermeer M, Kuper HH, Moens HJ, et al. Sustained beneficial effects of a protocolized treat-to-target strategy in very early rheumatoid arthritis: three-year results of the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring remission induction cohort. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:1219–26. 10.1002/acr.21984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakellariou G, Scire CA, Verstappen SM, et al. In patients with early rheumatoid arthritis, the new ACR/EULAR definition of remission identifies patients with persistent absence of functional disability and suppression of ultrasonographic synovitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:245–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balsa A, de Miguel E, Castillo C, et al. Superiority of SDAI over DAS-28 in assessment of remission in rheumatoid arthritis patients using power Doppler ultrasonography as a gold standard. Rheumatology 2010;49:683–90. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dale J SA, McInnes IB, Porter D. Targeting ultrasound remission in early rheumatoid arthritis—results of the taser study. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65(Suppl):338–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dale J, Purves D, McConnachie A, et al. Tightening up? Impact of musculoskeletal ultrasound disease activity assessment on early rheumatoid arthritis patients treated using a treat to target strategy. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:19–26. 10.1002/acr.22218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.