Abstract

Objectives

To compare the efficacy and safety of chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine hydrochloride (CS+GH) versus celecoxib in patients with knee osteoarthritis and severe pain.

Methods

Double-blind Multicentre Osteoarthritis interVEntion trial with SYSADOA (MOVES) conducted in France, Germany, Poland and Spain evaluating treatment with CS+GH versus celecoxib in 606 patients with Kellgren and Lawrence grades 2–3 knee osteoarthritis and moderate-to-severe pain (Western Ontario and McMaster osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) score ≥301; 0–500 scale). Patients were randomised to receive 400 mg CS plus 500 mg GH three times a day or 200 mg celecoxib every day for 6 months. The primary outcome was the mean decrease in WOMAC pain from baseline to 6 months. Secondary outcomes included WOMAC function and stiffness, visual analogue scale for pain, presence of joint swelling/effusion, rescue medication consumption, Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials and Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OMERACT-OARSI) criteria and EuroQoL-5D.

Results

The adjusted mean change (95% CI) in WOMAC pain was −185.7 (−200.3 to −171.1) (50.1% decrease) with CS+GH and −186.8 (−201.7 to −171.9) (50.2% decrease) with celecoxib, meeting the non-inferiority margin of −40: −1.11 (−22.0 to 19.8; p=0.92). All sensitivity analyses were consistent with that result. At 6 months, 79.7% of patients in the combination group and 79.2% in the celecoxib group fulfilled OMERACT-OARSI criteria. Both groups elicited a reduction >50% in the presence of joint swelling; a similar reduction was seen for effusion. No differences were observed for the other secondary outcomes. Adverse events were low and similarly distributed between groups.

Conclusions

CS+GH has comparable efficacy to celecoxib in reducing pain, stiffness, functional limitation and joint swelling/effusion after 6 months in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis, with a good safety profile.

Trial registration number:

Keywords: Analgesics, NSAIDs, Osteoarthritis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis in Western populations. It most frequently affects the knee, causing joint pain, tenderness, limitations of movement and impairment of quality of life, resulting in a social and economic burden.1 It accounts for a substantial number of healthcare visits and costs in populations with access to medical care.2 With increasing life expectancy, osteoarthritis is anticipated to become the fourth leading cause of disability by the year 2020.1

Standard treatment focuses on symptom relief with analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), though the latter can cause serious gastrointestinal and cardiovascular adverse effects, leading to concerns over long-term use.3–5

Various clinical trials have been performed with symptomatic slow-acting drugs for osteoarthritis (SYSADOA).6–9 Specifically, the Glucosamine/chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT) was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study comparing the efficacy and safety of glucosamine hydrochloride and chondroitin sulfate, alone and in combination, and celecoxib for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis.10 While no statistically significant effects were observed for the combination group in the overall study population, a significant difference was observed for the combination arm in patients with moderate-to-severe pain for the primary outcome, defined as a 20% decrease in Western Ontario and McMaster osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) pain score (p=0.002). Additionally, patients with moderate-to-severe pain showed significant differences in the combination versus placebo group for Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials and Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OMERACT-OARSI) response (p=0.001), 50% decrease in WOMAC pain (p=0.02), WOMAC pain score (p=0.009), WOMAC function score (p=0.008), normalised WOMAC score (p=0.017) and Health Assessment Questionnaire pain score (p=0.03).

To confirm these effects, the Multicentre Osteoarthritis interVEntion trial with Sysadoa (MOVES) was conducted to test whether chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine hydrochloride has comparable efficacy to celecoxib after 6 months of treatment in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis.

Methods

Study design

The MOVES trial was a phase IV, multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised, parallel-group, double-blind study. Patients were recruited consecutively by physicians in public or private practice at sites in France, Germany, Poland and Spain (see online supplementary table S1 for a list of investigators by study site and country).

Patients

Eligible patients were ≥40 years of age, with a diagnosis of primary knee osteoarthritis according to the American College of Rheumatology, with radiographic evidence (Kellgren and Lawrence grade 2 or 3) of osteoarthritis, and severe pain (WOMAC pain score ≥301 on a 0–500 scale) at inclusion. Patients were excluded if they had concurrent medical or arthritic conditions that could confound the evaluation of the index joint or coexisting disease that could preclude successful completion of the trial such as history of cardiovascular or gastrointestinal events and were excluded due to use of celecoxib. The full list of selection criteria is detailed in online supplementary table S2.

Treatment regimens and randomisation

Eligible subjects were randomised to 400 mg chondroitin sulfate plus 500 mg glucosamine hydrochloride (Droglican, Bioiberica, S.A., Barcelona, Spain) three times a day or 200 mg celecoxib (Celebrex, Pfizer) every day for 6 months. Subjects were assigned sequentially in a 1:1 ratio using a computer-generated randomisation list prepared by an independent biostatistician (GD) using proc Plan SAS System (V.9.1.3) software. Subjects receiving combination therapy took six capsules of chondroitin sulfate 200 mg plus glucosamine hydrochloride 250 mg per day; those receiving celecoxib took one celecoxib 200 mg plus one placebo capsule (in the morning) and four further placebo capsules per day. To maintain the blind (among patients, physicians, site staff and contract research organisation), celecoxib capsules were overencapsulated and placebo capsules had an identical appearance to the combination product. Patients were allowed to take up to 3 g/day of acetaminophen as rescue medication, except during the 48 h before clinical evaluation.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was defined as the mean decrease in WOMAC pain subscale from baseline to 6 months. Secondary efficacy outcome measures included: stiffness and function subscales of WOMAC; visual analogue scale; OMERACT-OARSI responder index;11 presence of joint swelling/effusion (see online supplementary table S3 for protocols for assessment); use of rescue medication (according to diary entries and tablet counts); patients’ and investigators’ global assessments of disease activity and response to therapy, and health status (EuroQol-5D) at 6 months. All outcome measures were assessed at 30, 60, 120 and 180 days.

Safety outcomes included discontinuation of study treatment due to adverse events (AEs), changes in various laboratory measures and vital signs.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated to test the non-inferiority of chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine hydrochloride versus celecoxib in the assessment of change in the WOMAC pain subscale. With 280 patients per group, the study would have 90% power assuming the expected difference in means was 0, the common SD was 26 (0–100 scale), according to previous studies,12–16 with a delta of eight units (0–100 scale),13 16 17 a one-sided significance level of 2.5% and assuming a 20% dropout rate. A delta of eight units in a range from 0 to 100 (the same as a delta of 40 units in the original range from 0 to 500) was used in the study.

The main analyses were performed using the per-protocol population, defined as all randomised patients meeting the inclusion criteria, who received study medication, had a baseline and at least one postbaseline efficacy measurement (for the primary efficacy variable) and did not have major protocol violations. In non-inferiority trials, the per-protocol set is used in the primary analysis as it is the most conservative approach. Additionally, the primary efficacy analysis was performed according to intention to treat to test the robustness of the results.18 19 The safety population was defined as all randomised subjects who took at least one dose of the study medication.

Continuous efficacy variables were analysed by means of a mixed models for repeated measurements (MMRM) approach, including time, treatment-by-time interaction and baseline value as a covariate. The variance–covariance matrix was unstructured. For categorical variables, Fisher's exact test was used for between-treatment comparisons, by time-point when applicable. Missing data in the main outcome were handled using a conservative approach by imputation using the dropout reason (IUDR) (the worst value for dropouts due to safety issues) or the last observation carried forward approach in case of lack of efficacy. Other reasons were not imputed and were handled by the MMRM approach, which relies on the missing at random assumption. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using the baseline observation carried forward (BOCF) and the MMRM with no imputation.

The analysis was performed using SAS V.9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA), and the level of significance was established at the 0.05 level (two-sided).

Results

Patient characteristics

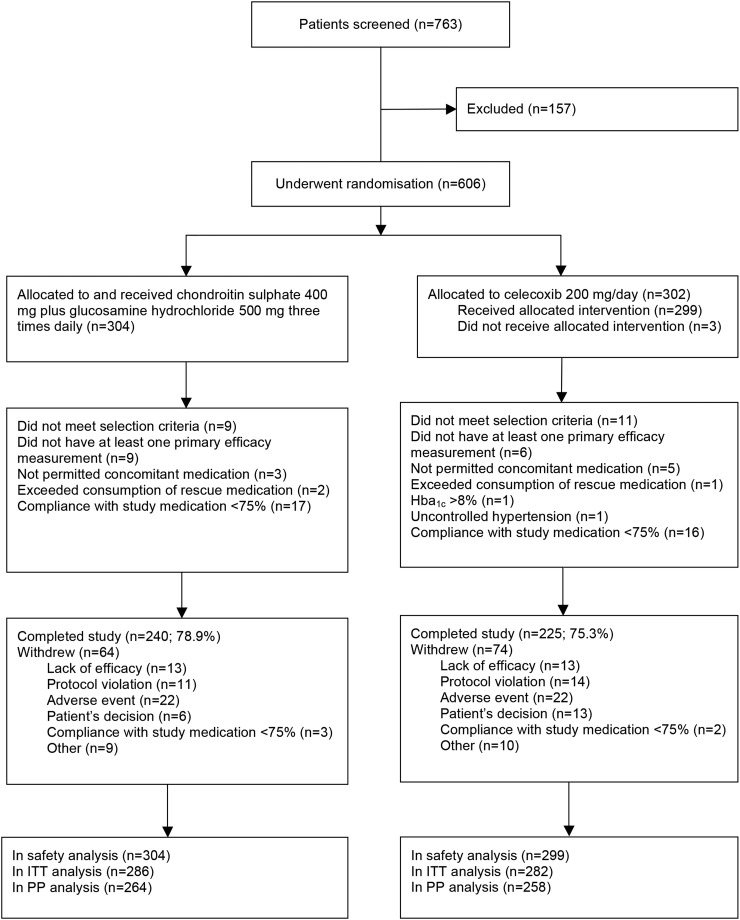

Recruitment began in September 2011 at 42 centres in France, Germany, Poland and Spain. The study was completed in April 2013. A total of 763 patients were screened and 606 underwent randomisation (figure 1). The main reasons for screen failure in 157 patients were high cardiovascular risk (n=36, 22.9%), patient decision (n=31, 19.8%) and low WOMAC pain score (n=23, 14.7%). Of the 606 subjects randomised, 568 (93.7%) were included in the intention-to-treat analysis and 522 (86.1%) in the per-protocol analysis. Of the 603 subjects included in the safety population, 465 (77.1%) completed the study, without differences between treatments (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of Multicentre Osteoarthritis interVEntion trial with SYSADOA (MOVES) patients. Hba1c, glycated haemoglobin; ITT, intention to treat; PP, per protocol.

The mean±SD age at baseline was 62.7±8.9 years, 438 (83.9%) were women and 515 (98.7%) were Caucasian. The overall mean WOMAC pain score was 371.3±41.6, and Kellgren and Lawrence grade 2 changes were present in 327 (62.6%) of the subjects. The groups were well balanced at baseline (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic | Chondroitin sulfate+glucosamine hydrochloride (n=264)* | Celecoxib (n=258)* |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62.2±8.8 | 63.2±9.0 |

| Women | 229 (86.7) | 209 (81.0) |

| White | 260 (98.5) | 255 (98.8) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 31.1±5.8 | 30.9±18.0 |

| Kellgren and Lawrence radiographic reading | ||

| Grade 2 | 165 (62.5) | 162 (62.8) |

| Grade 3 | 99 (37.5) | 96 (37.2) |

| Most common analgesics before inclusion | ||

| Acetaminophen | 74 (28.0) | 77 (29.8) |

| Ibuprofen | 45 (17.0) | 37 (14.3) |

| Diclofenac | 36 (13.4) | 40 (15.5) |

| WOMAC score (inclusion) | ||

| Pain scale | 372.0±41.8 | 370.6±41.4 |

| Stiffness scale | 130.2±35.0 | 129.5±37.2 |

| Function scale | 1131.4±242.7 | 1111.6±267.8 |

| Huskisson's visual analogue scale (pain intensity) | 72.8±15.1 | 73.5±15.1 |

| Joint swelling | 33 (12.5) | 36 (14) |

| Joint effusion | 18 (6.8) | 20 (7.8) |

| Patient's global assessment of disease activity | 69.1±17.3 | 69.4±16.4 |

| Investigator's global assessment of disease activity | 63.2±15.5 | 63.3±14.7 |

| EuroQol-5D (health-related quality of life) | ||

| Mobility | 1.8±0.4 | 1.8±0.4 |

| Self-care | 1.4±0.5 | 1.4±0.5 |

| Usual activities | 1.8±0.4 | 1.8±0.4 |

| Pain/discomfort | 2.3±0.4 | 2.3±0.4 |

| Anxiety/depression | 1.7±0.6 | 1.6±0.6 |

| Visual analogue scale | 54.5±20.3 | 52.5±20.7 |

Data are mean±SD or n (%).

*Continuous variables are mean±SD at baseline and baseline adjusted least-square means (95% CI) for other measurements; ordinal variables are mean±SD.

WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster osteoarthritis index.

Clinical outcomes

Efficacy

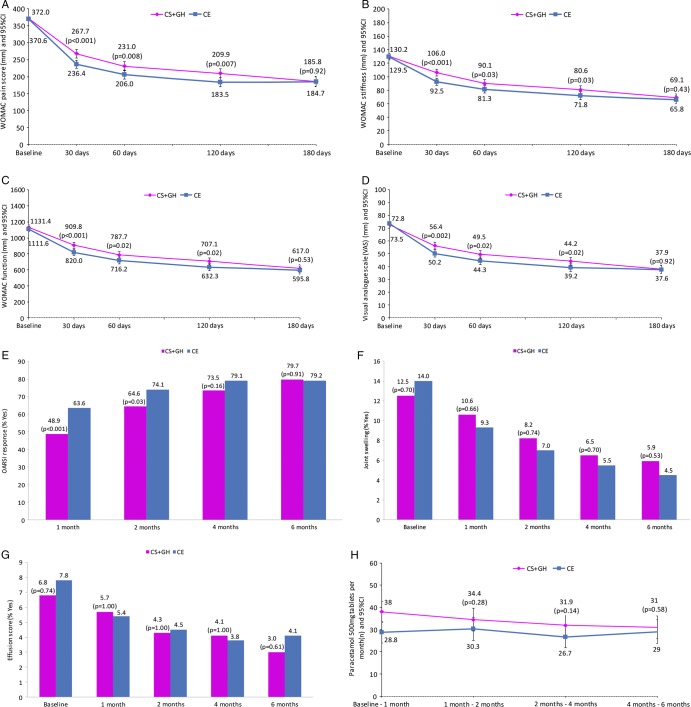

The primary and secondary efficacy outcomes are detailed in table 2 and figure 2.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary efficacy outcomes in per-protocol population

| Outcome | Chondroitin sulfate+glucosamine hydrochloride* |

Celecoxib* | p Value† | Treatment differences‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOMAC pain score (imputed data on per-protocol set) | ||||

| Baseline | 372.0±41.8 | 370.6±41.4 | ||

| 180 days | 185.8 (171.2 to 200.4) | 184.7 (169.8 to 199.6) | 0.92 | −1.1 (−22.0 to 19.8) |

| Change | −185.7 (−200.3 to −171.1) | −186.8 (−201.7 to −171.9) | ||

| WOMAC stiffness score | ||||

| Baseline | 130.2±35.0 | 129.5±37.2 | ||

| 180 days | 69.1 (63.3 to 74.8) | 65.8 (59.9 to 71.7) | 0.43 | −3.3 (−11.5 to 5.0) |

| Change | −60.4 (−66.1 to −54.7) | −63.7 (−69.6 to −57.8) | ||

| WOMAC function score | ||||

| Baseline | 1131.4±242.7 | 1111.6±267.8 | ||

| 180 days | 617.0 (570.8 to 663.2) | 595.8 (548.4 to 643.2) | 0.53 | −21.2 (−87.3 to 45.0) |

| Change | −504.4 (−550.6 to −458.2) | −525.6 (−573.0 to −478.3) | ||

| Huskisson's visual analogue scale | ||||

| Baseline | 72.8±15.1 | 73.5±15.1 | ||

| 180 days | 37.9 (34.7 to 41.0) | 37.6 (34.4 to 40.9) | 0.92 | −0.22 (−4.8 to 4.3) |

| Change | −35.1 (−38.3 to −31.9) | −35.3 (−38.6 to −32.1) | ||

| OMERACT-OARSI responder§ | 188 (79.7) | 175 (79.2) | 0.91 | |

| Joint swelling§ | 14 (5.9) | 10 (4.5) | 0.54 | |

| Joint effusion§ | 7 (3.0) | 9 (4.1) | 0.61 | |

| Consumption of rescue medication (days 120–180) | 31.0 (25.8 to 36.2) | 29.0 (23.6 to 34.3) | 0.58 | −2.1 (−9.5 to 5.4) |

| Patients’ global assessment of disease activity | ||||

| Baseline | 69.1±17.3 | 69.4±16.4 | ||

| 180 days | 38.3 (35.3 to 41.4) | 36.9 (33.8 to 40.0) | 0.51 | −1.5 (−5.8 to 2.9) |

| Change | −31.0 (−34.0 to −28.0) | −32.4 (−35.6 to −29.3) | ||

| Investigators’ global assessment of disease activity | ||||

| Baseline | 63.2±15.5 | 63.3±14.7 | ||

| 180 days | 35.3 (32.6 to 38.1) | 33.4 (30.6 to 36.2) | 0.33 | −1.9 (−5.8 to 2.0) |

| Change | −27.8 (−30.5 to −25.1) | −29.7 (−32.5 to −26.9) | ||

| Patients’ global assessment of response to therapy at 180 days | 36.8 (33.5 to 40.2) | 36.0 (32.6 to 39.5) | 0.74 | −0.8 (−5.6 to 4.0) |

| Investigators’ global assessment of response to therapy | 34.7 (31.6 to 37.9) | 33.8 (30.6 to 37.0) | 0.70 | −0.9 (−5.4 to 3.6) |

| EuroQol-5D | ||||

| Mobility | 1.5±0.03 | 1.5±0.03 | 0.16 | |

| Self-care | 1.2±0.03 | 1.2±0.03 | 0.94 | |

| Usual activities | 1.4±0.03 | 1.4±0.03 | 0.73 | |

| Pain/discomfort | 1.8±0.03 | 1.9±0.03 | 0.60 | |

| Anxiety/depression | 1.4±0.04 | 1.3±0.04 | 0.21 | |

| Visual analogue scale | 69.1±1.3 | 70.2±1.3 | 0.54 | |

*Continuous variables are mean±SD at baseline and MMRM model baseline adjusted least-square means (95% CI) for other measurements; ordinal variables are mean±SD.

†MMRM model p value of treatment effect.

‡MMRM model adjusted mean (95% CI).

§n (%) and Fisher's exact test p value.

MMRM, mixed models for repeated measurement; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster osteoarthritis index.

Figure 2.

Western Ontario and McMaster osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) (A) pain, (B) stiffness and (C) function subscales, and (D) visual analogue scale by visit; (E) Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials and Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OMERACT-OARSI) responder criteria, (F) joint swelling, (G) joint effusion and (H) consumption of rescue medication, by visit. The p values compare values between treatments. Data are least-square means±SEM. CE, celecoxib; CS+GH, chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine hydrochloride.

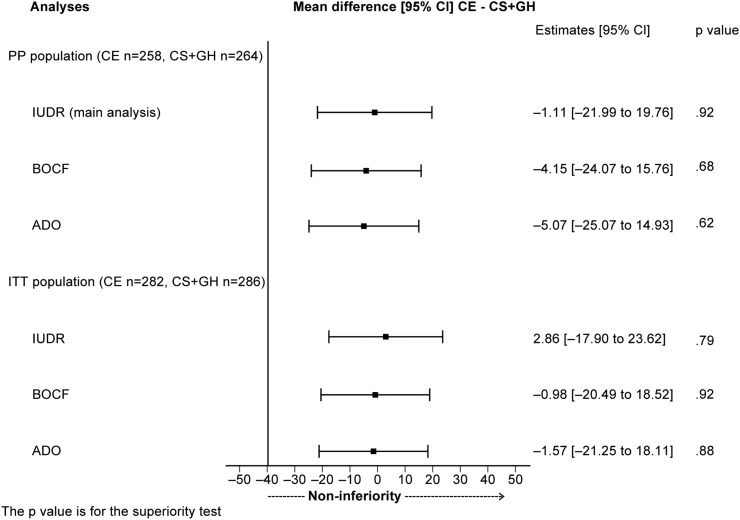

The mean change from baseline to 6 months in WOMAC pain score was −185.7 (−200.3 to −171.1) (a decrease of 50.1%) in the chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine group and −186.8 (−201.7 to −171.9) (a decrease of 50.2%) in the celecoxib group (figure 2A). The corresponding mean difference (95% CI) respected the non-inferiority margin of −40 units: −1.1 (−22.0 to 19.8; p=0.92) in the main analysis. All sensitivity analyses confirmed the non-inferiority conclusion (figure 3 and online supplementary table S4). There were no differences at 6 months between treatment groups in the WOMAC stiffness score, with a decrease of 46.9% in the combination group, compared with a decrease of 49.2% in the celecoxib group (p=0.43; figure 2B); WOMAC function score, with a decrease of 45.5% in the combination group compared with a decrease of 46.4% in the celecoxib group (p=0.53; figure 2C) and visual analogue scale, with a decrease of 48.0% in the combination group versus a decrease of 48.8% in the celecoxib group (p=0.92; figure 2D). Similarly, there were no differences in patients’ (p=0.51) and physicians’ (p=0.33) global assessments of disease activity or response to therapy (p=0.74 and 0.70, respectively). Over 70% of patients fulfilled the OMERACT-OARSI criteria in both treatments from 120 days onwards (p=0.16; figure 2E). At 6 months, both treatments achieved a 79% response rate (p=0.91; figure 2E). Both groups elicited a reduction from baseline >50% in joint swelling (figure 2F), from 12.5% (33/264) to 5.9% (14/264) for chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine, and from 14.0% (36/258) to 4.5% (10/258) for celecoxib (p=0.54). A similar reduction was also seen for effusions, from 6.8% (18/264) to 3.0% (7/264) and from 7.8% (20/258) to 4.1% (9/258), respectively (p=0.61; figure 2G). The consumption of rescue medication throughout the study was low and similar between treatments, except for the first month when use was higher in the combination group. No significant differences were observed afterwards (figure 2H).

Figure 3.

Mixed models for repeated measurements analysis, conducted using the following approaches for handling missing data: (A) imputation using drop-out reason (IUDR); (B) baseline observation carried forward (BOCF); and (C) available data only (ADO). The p value is for the superiority test. CE, celecoxib; CS+GH, chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine hydrochloride; ITT, intention to treat; PP, per protocol.

Health-related quality of life

All components of the EuroQoL-5D showed improvements over the treatment period in both groups. At 6 months, no differences were apparent between groups in terms of mobility (p=0.16), self-care (p=0.94), usual activities (p=0.73), pain/discomfort (p=0.60), anxiety/depression (p=0.21) or general health status measured by the visual analogue score (p=0.54; table 2).

Safety

The overall proportion of subjects having at least one treatment-emergent AE were 51.0% (155/304) in the chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine group and 50.5% (151/299) in the celecoxib group. In total, 17 of the AEs were serious, 7 (2.3%) in the chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine group and 10 (3.3%) in the celecoxib group. One serious AE was judged as definitely related to the study medication (allergic dermatitis) and one as possibly related (dizziness) (both in the celecoxib group); three serious AEs were judged to be probably related to the study group, two in the chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine group (Helicobacter pylori gastritis and allergic reaction) and one in the celecoxib group (dermatitis psoriaform). The other 12 were deemed to be unlikely or unrelated to study medication. No deaths occurred in this study. A total of 44 of 603 (7.3%) patients discontinued the study medication due to an AE, 22 in each treatment group (figure 1). Parameters determined from blood and urine, vital signs and physical examination were similar in both groups.

Discussion

The MOVES trial found that a fixed-dose combination of chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine has comparable efficacy to celecoxib in reducing pain in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee with moderate-to-severe pain after 6 months of treatment. The reduction in pain was both clinically important and statistically significant (50% reduction in both groups), as was the improvement in stiffness (46.9% reduction with the combination vs 49.2% with celecoxib), and function (45.5% vs 46.4%, respectively). Similar improvements were seen in visual analogue scale, the pain/discomfort dimension of EuroQoL-5D and patients’ and investigators’ assessments of disease activity and response to therapy without differences between treatments. Indeed, four-fifths of patients met the OMERACT-OARSI responder criteria in both groups. Other clinical symptoms, such as swelling/effusion, improved to the same extent in both groups and the consumption of rescue medication was similar. These results both confirm and extend those from the GAIT study in patients with severe knee pain.

Chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine have a slow onset of response and provide long-lasting pain relief and functional improvement in osteoarthritis.6–9 In the current study, celecoxib was superior to chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine at 1–4 months (in terms of WOMAC scores and Huskisson's visual analogue scale), but by 6 months, response to chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine was similar to celecoxib (see online supplementary table S4). Studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects of both glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate. Both inhibit metalloproteinase activity, prostaglandin E2 release, nitric oxide production and degradation of glycosaminoglycans, as well as stimulate the synthesis of hyaluronic acid in the joint. Chondroitin sulfate stimulates collagen synthesis, while glucosamine inhibits prostaglandin release.20–23 However, while each substance exerts beneficial effects on the processes underlying osteoarthritis, a number of studies have demonstrated that many of these effects benefit from the synergy observed with combined glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate treatment.24–27 In contrast, celecoxib inhibits prostaglandin biosynthesis, primarily through blocking the cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme, thereby achieving rapid reduction in signs and symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knee,28 but it does not alter other processes underlying the disease. This difference in the mechanisms of action is supported by the present results, which indicate more substantial and faster response for celecoxib than for chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine up to 120 days, but by 6 months there are no significant differences between the two treatments across all outcomes. Indeed, the overall pain improvement calculated using area under the curve analyses was superior with celecoxib than with the combination (p<0.001 for the imputed per-protocol population and p=0.002 for the imputed intention-to-treat sensitivity population).

Both treatments had a good safety profile and tolerability in this population, which excluded patients with high cardiovascular or gastrointestinal risk. Celecoxib is recognised to increase the risk of cardiovascular thrombotic events, congestive heart failure and major gastrointestinal events compared with placebo,5 and, in the European Union, is contraindicated in patients with known cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disease. Around half of the patients in each group had at least one AE, most of which were of mild or moderate intensity, with only 17 events classified as serious. The observed tolerability in both groups was as expected from previous studies, such as GAIT.10

While the present results are in accordance with data from other studies for the combination,10 29 30 and for celecoxib in painful knee osteoarthritis at the same dosage,10 12–14 22 direct comparisons are limited by differences in study designs and drug formulations. The only randomised double-blind study that allows the comparison of the combination of chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine with celecoxib was the GAIT study.10 The data of efficacy and safety in the present study are consistent with those from GAIT in patients with severe knee pain.

Chondroitin and glucosamine have been recommended in some practice guidelines for the treatment of osteoarthritis.31–33 Both chondroitin sulfate and the two commercially available salts of glucosamine hydrochloride or sulfate are available as prescription medicines in the European Union for the treatment of osteoarthritis. The clinical evidence to support these medications is, however, conflicting.10 34–38 Consequently, current evidence-based guidelines on the management of osteoarthritis focus on topical treatments and oral analgesics,31 39 40 and some39 40 advise against treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine on the basis of lack of efficacy evidence, but not on potential harm.39 Conversely, the suboptimal efficacy and possibility of serious adverse drug reactions with long-term use of analgesics, NSAIDs and opioids are well recognised.

The present study, conducted in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee with severe pain, provides robust data to demonstrate the long-term efficacy and safety of chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine in the management of these patients, and suggests that this combination may, in addition, offer an alternative, especially for individuals with cardiovascular or gastrointestinal conditions who have contraindications for treatment with NSAIDs.

This study has some limitations. The preparation of chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine used has been approved as a prescription drug, and the present results cannot therefore be generalised to other compound mixtures, such as commercially available dietary supplements in the UK and the USA, or to the individual components themselves. As patients with known cardiovascular disease and those at high risk for both cardiovascular and gastrointestinal disease were not included, it is not possible to extend the safety of the combination to this population. The study was designed as a non-inferiority trial with two active treatment arms. The use of a placebo group was not considered appropriate for ethical and methodological reasons. A non-inferiority trial requires that the reference treatment's efficacy is established or is in widespread use, as is the case for celecoxib, so that a placebo or untreated control group would be deemed unethical.41 This is of special relevance in this specific patient population with moderate-to-severe pain. Furthermore, the use of a placebo arm was not considered necessary as the design of the MOVES study was similar to that of the GAIT study, which already compared both active treatments with placebo. Additionally, both treatment groups have already demonstrated superiority compared with placebo in former randomised controlled trials.12–15 17 29 30

These results confirm that the combination of chondroitin sulfate plus glucosamine hydrochloride has proven non-inferior to celecoxib in reducing pain. No differences were found for stiffness, functional limitations, joint swelling and effusion after 6 months of treatment in patients with severe pain from osteoarthritis of the knee, and the combination has a similar good safety profile and tolerability. This combination of SYSADOA appears to be beneficial in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee and should offer a safe and effective alternative for those patients with cardiovascular or gastrointestinal conditions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. Figure 1 has been corrected.

Collaborators: MOVES Investigator Group.

Contributors: MCH, JM-P and J-PP contributed equally to this work. MCH had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. MCH, JM-P, JM, IM, JRC, NA, FB, FJB, PGC, GD, YH, TP, PR, AS, PdS and J-PP were responsible for study concept and design, acquisition, analysis or interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript and study supervision. IM, JRC, NA, FB, FJB, PGC, GD, TP, PR, AS, PdS and J-PP were responsible for critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. GD was responsible for the statistical analysis. Additional contributions: Sophie Rushton-Smith, PhD (Medlink Healthcare Communications, UK) drafted the paper based on detailed information and guidance provided by the lead author, including published abstracts, and information provided by the sponsor, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan and results. She also coordinated and integrated the comments and modifications suggested by all authors upon review. Her effort was funded by Bioiberica SA.

Funding: This trial was funded by Bioiberica SA, Barcelona, Spain. The sponsor provided all of the study medication free of charge and met the expenses that arose during the course of the study. The sponsor also participated in the study design and data interpretation.

Competing interests: MH is a consultant to Bioiberica SA, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono SA, Iroko Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharma AG, Pfizer, Samumed LLC and Theralogix LLC, and owns stock in Theralogix LLC. JM-P is a shareholder of ArthroLab and has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Bioiberica, Merck & Co, Servier, and TRB Chemedica. JM received personal fees for lectures from Bioiberica SA and Merck Sharp & Dohme during the 36 months prior to this publication. FJB has received grants (for clinical trials, conferences, advisory work, and publications) from Abbvie, Amgen, Bioiberica, Bristol Mayer, Celgene, Celltrion, Cellerix, Grunenthal, Gebro Pharma, Lilly, MSD, Merck Serono, Pfizer, Pierre-Fabra, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Tedec-Meiji and UCB. YH has received speaker fees from IBSA, Bioiberica and Expanscience, consulting fees from Galapagos, Flexion, Tilman SA, Artialis SA and Synolyne Pharma, and research grants from Nestec, Bioiberica, Royal Canin and Artialis SA. PdS acts as a consultant for WEX Pharmaceuticals and has received payment for lectures from Bioiberica. J-PP is a shareholder of ArthroLab and has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Bioiberica, Merck & Co, Servier and TRB Chemedica.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Local health authorities and the institutional review board of each centre approved the study. The trial was performed according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and to Good Clinical Practice.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional unpublished data from the MOVES trial may be obtained by contacting Dr. Josep Verges, c/o Bioiberica S.A., Barcelona, Spain.

References

- 1.Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81:646–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smalley WE, Ray WA, Daugherty JR, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the incidence of hospitalizations for peptic ulcer disease in elderly persons. Am J Epidemiol 1995;141:539–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1888–99. 10.1056/NEJM199906173402407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists' (CNT) Collaboration, Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, et al Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2013;382:769–79. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60900-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uebelhart D, Malaise M, Marcolongo R, et al. Intermittent treatment of knee osteoarthritis with oral chondroitin sulfate: a one-year, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study versus placebo. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12:269–76. 10.1016/j.joca.2004.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morreale P, Manopulo R, Galati M, et al. Comparison of the antiinflammatory efficacy of chondroitin sulfate and diclofenac sodium in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 1996;23:1385–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reginster JY, Deroisy R, Rovati LC, et al. Long-term effects of glucosamine sulphate on osteoarthritis progression: a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet 2001;357:251–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03610-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrero-Beaumont G, Ivorra JA, Del Carmen Trabado M, et al. Glucosamine sulfate in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study using acetaminophen as a side comparator. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:555–67. 10.1002/art.22371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med 2006;354:795–808. 10.1056/NEJMoa052771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pham T, van der Heijde D, Altman RD, et al. OMERACT-OARSI initiative: Osteoarthritis Research Society International set of responder criteria for osteoarthritis clinical trials revisited. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12:389–99. 10.1016/j.joca.2004.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bingham CO, Bird SR, Smugar SS, et al. Responder analysis and correlation of outcome measures: pooled results from two identical studies comparing etoricoxib, celecoxib, and placebo in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:1289–93. 10.1016/j.joca.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bingham CO, Sebba AI, Rubin BR, et al. Efficacy and safety of etoricoxib 30 mg and celecoxib 200 mg in the treatment of osteoarthritis in two identically designed, randomized, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority studies. Rheumatology 2007;46:496–507. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bingham CO, Smugar SS, Wang H, et al. Early response to COX-2 inhibitors as a predictor of overall response in osteoarthritis: pooled results from two identical trials comparing etoricoxib, celecoxib and placebo. Rheumatology 2009;48:1122–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rother M, Lavins BJ, Kneer W, et al. Efficacy and safety of epicutaneous ketoprofen in Transfersome (IDEA-033) versus oral celecoxib and placebo in osteoarthritis of the knee: multicentre randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1178–83. 10.1136/ard.2006.065128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnitzer TJ, Kivitz A, Frayssinet H, et al. Efficacy and safety of naproxcinod in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a 13-week prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:629–39. 10.1016/j.joca.2009.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birbara C, Ruoff G, Sheldon E, et al. Efficacy and safety of rofecoxib 12.5 mg and celecoxib 200 mg in two similarly designed osteoarthritis studies. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:199–210. 10.1185/030079906X80242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Conference on Harmonization (ICH). ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline Topic E9: Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials 1998. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500002928.pdf

- 19.Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP). CPMP/EWP/482/99 Final. Points to consider on switching between superiority and non-inferiority. London: European Medicines Agency, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.du Souich P. Absorption, distribution and mechanism of action of SYSADOAS. Pharmacol Ther 2014;142:362–74. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calamia V, Ruiz-Romero C, Rocha B, et al. Pharmacoproteomic study of the effects of chondroitin and glucosamine sulfate on human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:R138 10.1186/ar3077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bensen WG, Fiechtner JJ, McMillen JI, et al. Treatment of osteoarthritis with celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc 1999;74:1095–105. 10.4065/74.11.1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henrotin Y, Lambert C. Chondroitin and glucosamine in the management of osteoarthritis: an update. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2013;15:361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lippiello L, Woodward J, Karpman R, et al. In vivo chondroprotection and metabolic synergy of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000(381):229–40. 10.1097/00003086-200012000-00027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarty MF, Russell AL, Seed MP. Sulfated glycosaminoglycans and glucosamine may synergize in promoting synovial hyaluronic acid synthesis. Med Hypotheses 2000;54:798–802. 10.1054/mehy.1999.0954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orth MW, Peters TL, Hawkins JN. Inhibition of articular cartilage degradation by glucosamine-HCl and chondroitin sulphate. Equine Vet J Suppl 2002(34):224–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan PS, Caron JP, Rosa GJ, et al. Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate regulate gene expression and synthesis of nitric oxide and prostaglandin E(2) in articular cartilage explants. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005;13:387–94. 10.1016/j.joca.2005.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKenna F, Borenstein D, Wendt H, et al. Celecoxib versus diclofenac in the management of osteoarthritis of the knee. Scand J Rheumatol 2001;30:11–18. 10.1080/030097401750065265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leffler CT, Philippi AF, Leffler SG, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin, and manganese ascorbate for degenerative joint disease of the knee or low back: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Mil Med 1999;164:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Das A Jr, Hammad TA. Efficacy of a combination of FCHG49 glucosamine hydrochloride, TRH122 low molecular weight sodium chondroitin sulfate and manganese ascorbate in the management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2000;8:343–50. 10.1053/joca.1999.0308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: Report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1145–55. 10.1136/ard.2003.011742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porcheret M, Jordan K, Croft P, et al. Treatment of knee pain in older adults in primary care: development of an evidence-based model of care. Rheumatology 2007;46:638–48. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruyere O, Burlet N, Delmas PD, et al. Evaluation of symptomatic slow-acting drugs in osteoarthritis using the GRADE system. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008;9:165 10.1186/1471-2474-9-165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Gulin JP, et al. Glucosamine and chondroitin for treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic quality assessment and meta-analysis. JAMA 2000;283:1469–75. 10.1001/jama.283.11.1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichenbach S, Sterchi R, Scherer M, et al. Meta-analysis: chondroitin for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:580–90. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hochberg MC, Zhan M, Langenberg P. The rate of decline of joint space width in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials of chondroitin sulfate. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:3029–35. 10.1185/03007990802434932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wandel S, Juni P, Tendal B, et al. Effects of glucosamine, chondroitin, or placebo in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: network meta-analysis. Bmj 2010;341:c4675 10.1136/bmj.c4675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee YH, Woo JH, Choi SJ, et al. Effect of glucosamine or chondroitin sulfate on the osteoarthritis progression: a meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int 2010;30:357–63. 10.1007/s00296-009-0969-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Evidence-based guideline.

- 40.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Clinical Guideline 177. Osteoarthritis. Care and management in adults 2014. http://publications.nice.org.uk/osteoarthritis-cg177

- 41.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, et al. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 2006;295:1152–60. 10.1001/jama.295.10.1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.