Abstract

Purpose

Taxane induced peripheral neuropathy (TIPN) is an important survivorship issue for many cancer patients. Currently, there are no clinically implemented biomarkers to predict which patients might be at increased risk for TIPN. We present a comprehensive approach to identification of genetic variants to predict TIPN.

Experimental Design

We performed a genome wide association study (GWAS) in 3431 patients from the phase III adjuvant breast cancer trial, ECOG-5103 to compare genotypes with TIPN. We performed candidate validation of top SNPs for TIPN in another phase III adjuvant breast cancer trial, ECOG-1199.

Results

When evaluating for Grade 3-4 TIPN, 120 SNPs had a p-value <10−4 from patients of European descent (EA) in ECOG-5103. 30 candidate SNPs were subsequently tested in ECOG-1199 and SNP rs3125923 was found to be significantly associated with Grade 3-4 TIPN (p=1.7×10−3; OR=1.8). Race was also a major predictor of TIPN, with patients of African descent (AA) experiencing increased risk of Grade 2-4 TIPN (HR=2.1; p=5.6×10−16) and Grade 3-4 TIPN (HR=2.6; p=1.1×10−11) compared with others. A SNP in FCAMR, rs1856746, had a trend toward an association with Grade 2-4 TIPN in AA patients from the GWAS in ECOG-5103 (OR=5.5; p=1.6×10−7).

Conclusion

rs3125923 represents a validated SNP to predict Grade 3-4 TIPN. Genetically determined AA race represents the most significant predictor of TIPN.

Keywords: Peripheral neuropathy, Taxanes, Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), Genome wide association study (GWAS), Genetic biomarker

INTRODUCTION

The taxanes are commonly used to treat patients with a variety of malignancies.(1, 2) While having improved outcomes, taxanes are not without toxicity. One of the most common toxicities is taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy (TIPN). TIPN can substantially impact quality of life, can be irreversible, and limit drug exposure; occasionally requiring cessation of treatment. The likelihood of TIPN depends on the type of taxane used, dose, and schedule.(3) However, there is also substantial inter-individual heterogeneity and it is difficult to predict which patients will be at greatest risk for TIPN prior to receipt. Several trials have previously been published evaluating the impact of germline genetic variation on likelihood of TIPN with variable results. These studies have varied widely in size, disease setting, phenotype definition, and genotype methodology.(4-12) Here we investigated genetic biomarkers of TIPN in two large, adjuvant breast cancer trials that incorporated taxanes; ECOG-5103(13) and ECOG-1199.(14)

METHODS

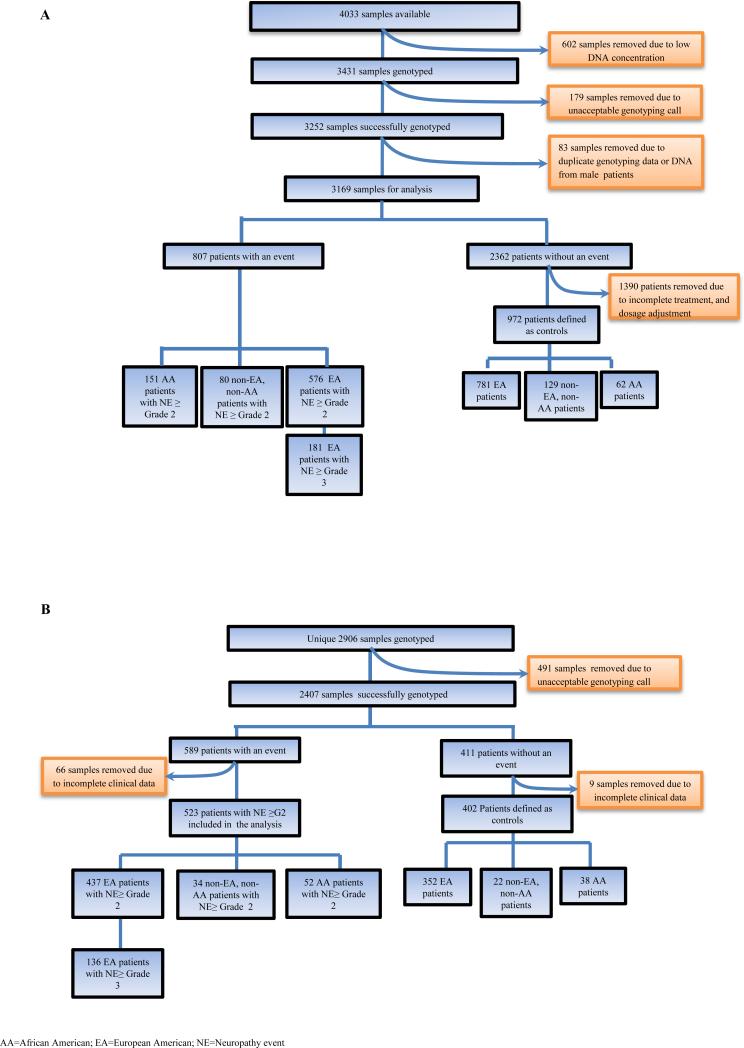

Genome wide association study (GWAS) for SNP discovery in ECOG-5103

ECOG-5103 (Figure 1A) was a phase III adjuvant breast cancer trial that randomized 4994 patients with node positive or high-risk node negative breast cancer to intravenous doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide every 2 or 3 weeks (at discretion of treating physician) for four cycles (AC) followed by 12 weeks of weekly paclitaxel (P; 80 mg/m2) alone (Arm A) or to the same chemotherapy with either concurrent bevacizumab (Arm B) or concurrent plus sequential bevacizumab (Arm C).(13) Germline (blood) DNA was available from 4033 patients. Genome-wide analyses were performed across all Arms to identify genotypes at single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were associated with TIPN.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram

(A) ECOG-5103 (the genome wide discovery cohort)

(B) ECOG-1199-(the candidate SNP validation cohort)

ECOG-5103 case/control definitions for TIPN

Cases

Cases were defined as those experiencing Grade 2-4 TIPN (n=576 EA, 151AA) as assessed by the Common Toxicity Criteria Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0. We separately assessed for those with the more extreme phenotype of Grade 3-4 (n=181 EA). Cases included patients who received at least one dose of paclitaxel and the neuropathy event occurred during treatment or within 3 months of the last dose of therapy.

Controls

Controls (n=781EA, 62AA) included patients who met all the following: 1). Received all planned doses of paclitaxel; 2). Had follow-up for at least 3 months after the last dose of drug; 3). Did not meet any of the case definitions as outlined above; and 4). Had either paclitaxel or bevacizumab held or modified for any reason (i.e. disease progression or other toxicity) were excluded.

Genotyping and Statistical analysis

Genotyping was performed in two distinct study subsets as described previously.(15) Genotyping array data was obtained on Illumina products and extensive quality review was performed to assure SNP quality, develop principal components for race assignment and imputation (see Supplemental Methods). Analyses were performed in genetically defined EA and AA subsets of the E5103 samples.

A Kaplan-Meier curve was plotted to evaluate the time to first neuropathy event. The association between race and time to first neuropathy was evaluated with Cox proportional hazards model, and their associated hazard ratios and p-values are reported. In the subsequent genetic association analysis, a standard case-control association analysis (logistic regression) was performed to identify SNPs associated with the presence or absence of TIPN. Principal component (PC) (Supplementary Figure 1), age, body surface area (BSA), Arm of study, menopausal status, and ER/PR status were considered as potential covariates. The threshold was set at p < 0.05 for inclusion of a covariate in the logistic regression model. PC1, age and BSA were significant predictors and were used in subsequent association analyses. The individual SNP effect is reported as odds ratio (OR) and p-value. SNPs available on the HumanOmni1-Quad array were included in the statistical analysis. An additive model of SNP effect was used and the analysis was performed using SNPTEST v2.4.(16) To correct for multiple SNP comparisons, the p-value threshold for genome wide significance was set at 5×10−8.(17)

Candidate SNP validation in ECOG-1199

ECOG-1199 (Figure 1B) was a phase III adjuvant breast cancer trial that randomized 5,052 patients to one of four treatment arms.(14) First, all patients received four cycles of AC every 3 weeks followed by P at 175 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for four cycles, or P at 80 mg/m2 weekly for 12 weeks, docetaxel (T) 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for four cycles, or T at 35 mg/m2 weekly for 12 weeks. Tumor derived DNA (formalin fixed paraffin embedded; FFPE) was available from 2906 patients. ECOG-1199 case and control designation were identical to that used for ECOG-5103 except CTC v2.0 definitions were used.

Top candidate SNPs (n=51) from the Grade 3-4 TIPN GWAS in ECOG-5103 were evaluated in ECOG-1199 (Supplementary Table 1). Only one SNP from each linkage disequilibrium (LD) block was selected to optimize coverage as well as to minimize corrections for multiple comparisons. Details regarding SNP selection, genotyping and quality review are available in the Supplemental Methods. Ancestry informative markers were not available, and thus analyses were performed separately for those of self-defined Caucasian race. The same logistic regression model used in the ECOG-5103 analyses was employed in the ECOG-1199 statistical analysis. Both OR and p-value were reported. The p-value threshold for candidate SNP significance was set at 1.7 × 10−3 based on correction for the 30 successfully genotyped SNPs tested. All covariates used in ECOG-5103 were included in the ECOG-1199 analyses.

RESULTS

Rates of TIPN and clinical predictors

ECOG-5103

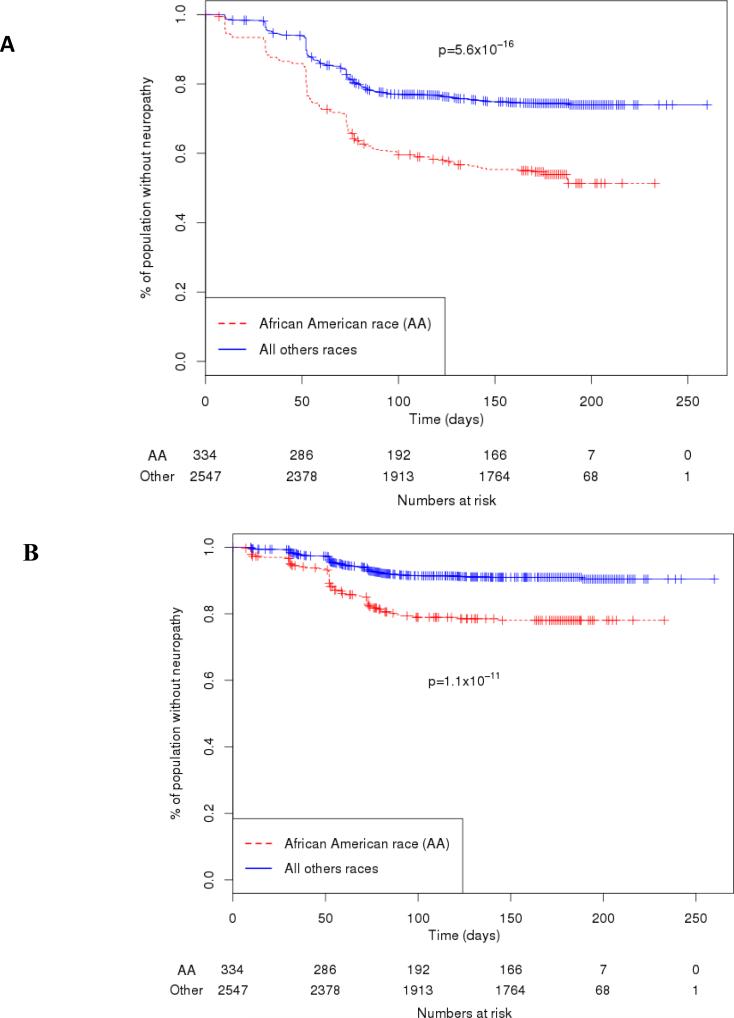

For the parent trial, depending on treatment arm 26-28% and 8-9% experienced TIPN of CTCAE v3.0 Grade 2-4 and 3-4 severity, respectively.(13) For the subset of 3169 patients who had analyzable genetic data, the risk of Grade 2-4 and Grade 3-4 TIPN was 27.6 % and 9.6 % respectively. Older age was a significant risk factor with a 13% increased risk per decade of life (p=9.3×10−4). Increased BSA was also significantly associated with an increased risk of neuropathy (HR=2.8; p=7.1×10−11). Race was genetically determined and those of African descent were markedly more likely to experience Grade 2-4 (HR=2.1; p=5.6×10−16) and Grade 3-4 (HR=2.6; p=1.1×10−11) TIPN compared to other races (Figure 2). This remained significant for both Grade 2-4 (p=5.6 ×10−14) and Grade 3-4 TIPN (p=1.4×10−11) when correcting for both age and BSA. Additionally, the degree of PC1 after correction for age and BSA was even more significantly associated with Grade 2-4 (HR=0.5; p=9.4×10−15) and Grade 3-4 (HR=0.37; p=7.4×10−13) TIPN.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Grade 2-4 and Grade 3-4 peripheral neuropathy by genetically determined race in ECOG-5103.

(A) The frequency of Grade 2-4 peripheral neuropathy in the genotyped cohort was 43.3% for those of African descent vs. 24.6% for all other races combined (p-value=5.6 ×10−16). The number of patients that had follow-up data and were still at risk for neuropathy at each time point is displayed below.

(B) The frequency of G3-4 peripheral neuropathy in the genotyped cohort was 18.4% for those of African descent vs. 8.1% for all other races combined (p-value=1.1 × 10−11). The number of patients that had follow up data and were still at risk for neuropathy at each time point is displayed below.

ECOG-1199

For the parent trial, depending on treatment arm 16-27% and 4-8% experienced TIPN of CTC v2.0 Grade 2-4 and 3-4 severity, respectively.(14) For the subset of 2906 patients who had analyzable genetic data, the risk of Grade 2-4 and Grade 3-4 TIPN was 19.8% and 6.2% respectively. For the parent trial, race was determined by self-report and was not associated with risk of TIPN for the entire cohort but there was a strong trend for increased risk in the weekly paclitaxel arm with a similar odds ratio to that seen in ECOG-5103.(18) Age was not significant but was considered as a covariate to maintain consistency across trials. Increased BSA (OR=1.9; p=0.0062) was significantly associated with an increased risk of neuropathy.

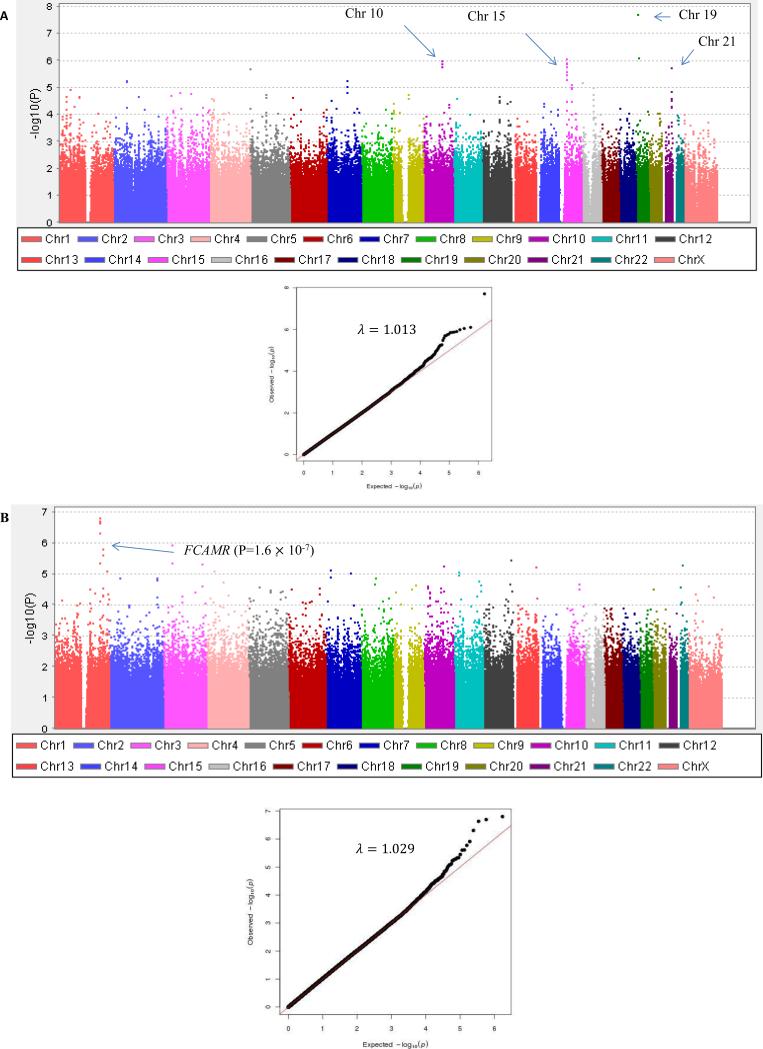

GWAS results for TIPN in EA subset from ECOG-5103

The strength of association between genotype and Grade 3-4 TIPN (Figure 3) and Grade 2-4 TIPN are demonstrated in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3, respectively. 120 and 65 SNPs had a p-value <1×10−4 for the Grade 3-4 analysis and the Grade 2-4 analysis, respectively.

Figure 3.

Manhattan plot (A) for Grade 3-4 peripheral neuropathy from EA patients in ECOG-5103. X-axis indicates the chromosomal position of each SNP analyzed; Y-axis denotes magnitude of the evidence for association, shown as –log10(p-value). (B) Grade 2-4 peripheral neuropathy from AA patients in ECOG-5103. X-axis indicates the chromosomal position of each SNP analyzed; Y-axis denotes magnitude of the evidence for association, shown as –log10(p-value).

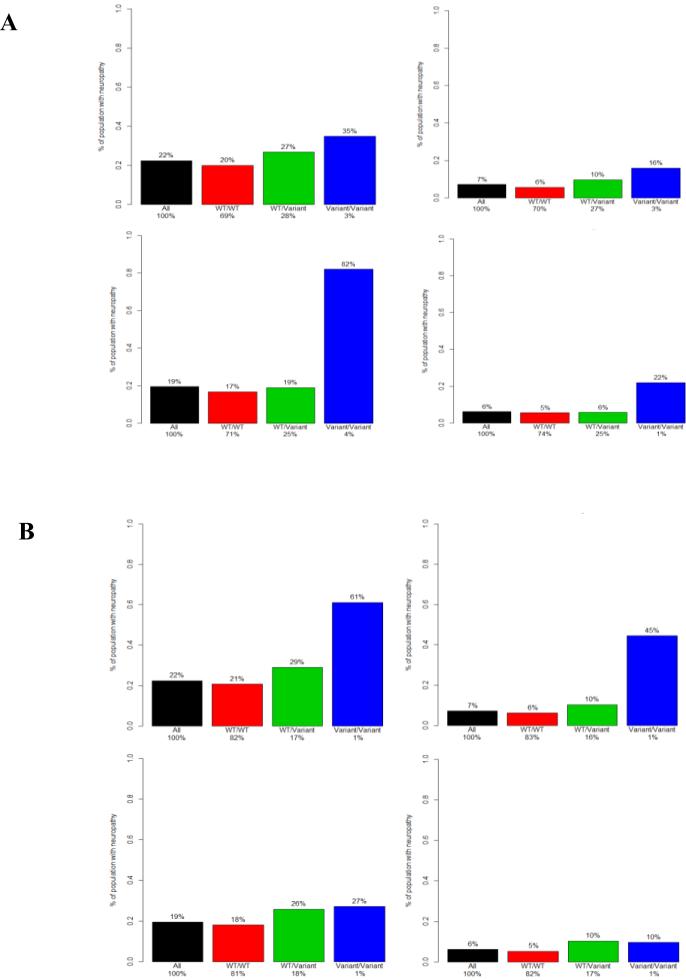

Evaluation of top EA SNPs in ECOG-1199

30 SNPs were evaluated in ECOG-1199 based on p-value and LD support (Supplementary Table 4). One SNP, rs3125923, was statistically significantly associated with increased risk of TIPN for Grade 3-4 severity after correction of multiple comparisons (p=1.7×10−3; OR=1.8). A second SNP, rs9862208, had a strong trend toward association with increased risk of TIPN for Grade 3-4 severity (p=5.9×10−3; OR=1.9); (Table 1; Figure 4).

Table 1.

SNPs with strongest statistical significance (based on p-value) from samples of European Ancestry in ECOG-1199 validation study

| SNP | Chr | E5103 G3-4 P-value | OR | E1199 G3-4 P-value | OR | E5103 G2-4 p-value | OR | E1199 G 2-4 p-value | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs3125923 | 1 | 5.0 ×10−5 | 1.8 | 0.0017 | 1.8 | 0.0001 | 1.5 | 0.0013 | 1.6 |

| rs9862208 | 3 | 8.5×10−5 | 2.0 | 0.0059 | 1.9 | 0.0002 | 1.6 | 0.0174 | 1.5 |

SNP=single nucleotide polymorphism; Chr=chromosome; OR=odds ratio; G3-4=Grade 3-4; G2-4=Grade 2-4

Figure 4.

Frequency of peripheral neuropathy by genotype for rs3125923 and rs9862208. Each colored bar represents the estimated frequency of neuropathy based on the relative likelihood of an event derived from a genotype. The black bar represents the frequency of neuropathy in the entire E5103 genotyped cohort. The red, green, and blue bars represent an estimated frequency as determined by the odds ratio for the WT/WT, WT/Variant, and Variant/Variant genotypes, respectively. The percentage value above each bar represents the estimated likelihood of a patient with that genotype experiencing neuropathy. The percentage value on the x-axis represents the fraction of the population with that specific genotype. WT= wild type allele.

(A) Frequency of neuropathy by genotypes of rs3125923 in ECOG-5103 (top) and ECOG-1199 (bottom) for grade 2-4 neuropathy (left) and grade 3-4 neuropathy (right).

(B) Frequency of neuropathy by genotypes of rs9862208 in ECOG-5103 (top) and ECOG-1199 (bottom) for grade 2-4 neuropathy (left) and grade 3-4 neuropathy (right).

GWAS results for TIPN in AA subset from ECOG-5103

Given the marked increased risk of TIPN among the AA subset, we performed an exploratory analysis for AA patients for Grade 2-4 TIPN (insufficient cases for Grade 3-4). The strength of association between genotype and TIPN are shown in Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 5. 112 SNPs had a p-value <1×10−4. A SNP near FCAMR, rs1856746, had a trend toward a significant association (p=1.6×10−7; OR= 5.5).

DISCUSSION

TIPN is considered one of the most important survivorship concerns for cancer patients.(19) There are established predictors of TIPN such as type and schedule of taxane.(18) Other demographic variables such as obesity and age are recognized to predispose as well.(18) Despite this, it is very difficult to predict which patients will ultimately develop neuropathy and which are at greatest risk for severe or irreversible TIPN. The heterogeneity of TIPN cannot be explained by differences in demographic variables alone suggesting the contributions of genetic variability. Several prior studies have demonstrated common SNP associations with TIPN,(4-9) although the clinical relevance is unclear.

In our analysis confined to EA patients, the more extreme phenotype data (Grade 3-4) provided the most impressive associations in terms of statistical significance despite smaller sample size. This suggests that there is an advantage to use of clearly defined, extreme phenotypes.(20) Although none of the SNPs in ECOG-5103 met genome wide significance, there were 120 SNPs with modest association and p-values <1.0 × 10−4. In our validation study from ECOG-1199, 58.8% of SNPs genotyped had an acceptable call rate ≥ 95% which is similar to previously reported data on FFPE samples.(21) We identified a SNP, rs3125923, that was associated with a statistically significant increased risk for TIPN. rs3125923 is a variant in a gene desert on chromosome 1 and had LD support in our analysis (Supplementary Figure 2). While understanding the functional implications of predictive SNPs is important, more than 80% of prior GWAS identified trait loci are in the non-coding regions of the genome,(22) as was the case here. Prior work has demonstrated that SNPs in gene deserts can have substantial consequences for regulation through alterations in gene expression, RNA splicing, transcription factor binding, chromatin openness as measured by DNase I hypersensitivity, DNA methylation and histone modification.(22) Recent expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) mapping has shown that rs3125923 alters GPR177 (G-Protein couple receptor gene) expression via trans-regulatory elements.(23) GPR177, also called the Wntless gene, encodes a receptor for Wnt proteins in Wnt secreting cells. Wnt, which is essential for neuronal development,(24) can sensitize peripheral sensory neurons via distinct noncanonical pathways.(25) These studies suggest downstream work should examine the impact of rs3125923 on expression of GPRR177 in neurons and the impact of differential GPR177 expression on taxane induced neuronal damage.

Prior studies (Table 2) have evaluated the role of genetic variation on likelihood of TIPN. Several have taken a candidate SNP-based approach with focus on metabolism,(5) transport,(10) paclitaxel binding site,(6, 10) and DNA repair genes.(7) Hertz et al.(5) demonstrated a trend toward greater likelihood of TIPN for those who carry the CYP2C8*3 variant. Apellaniz-Ruiz et al. performed whole exome sequencing on 8 patients with severe TIPN and found two with rare CYP3A4 variants that resulted in reduced enzyme expression.(11) Although not seen in any of the larger genome wide studies, the high-throughput panels are not optimally designed to evaluate for many of the CYP P450 metabolism enzymes and thus these findings should be further explored. Sucheston et al(7), Leandro-Garcia et al(6), and Abraham et al,(10) all identified associations between TIPN and SNPs from candidate genes with plausible biological rationale. Unfortunately, these did not include an independent validation cohort and were not reported as significant in the large genome wide data sets. Baldwin et al,(4) performed a GWAS in a large phase III adjuvant clinical trial. The top associations were SNPs in the genes FDG4, EPHA5, and FZD3, although the first two did not meet genome wide significance. They subsequently performed validation in a smaller cohort of patients and found an association with FDG4. Leandro-Garcia et al.(8) also performed a GWAS on 144 patients and found a modest association with a SNP in EPHA4 although no validation was performed. They did, however, perform a meta-analysis combining their data with the CALGB40101 trial(4) and found a significant p-value with a SNP in EPHA5. Although provocative, the SNP in EPHA5 did not validate in the independent validation cohort from the CALGB40101 trial and was not significant in our trial. Beutler et al.(9) performed massively parallel sequencing of 49 genes important for Charcot-Marie-Tooth in 119 patients. In this study, several SNPs in ARHGEF10 had modest association with high odds ratio. Unfortunately validation of rare SNPs is difficult using the standard GWAS platforms, which are traditionally built to evaluate common variants.

Table 2.

Selected SNPs previously reported to be associated with taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy

| Author | Number of patients | Clinical trial | Drugs | Phenotype | Genotypes | Genes of Top Associations | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sucheston (7) |

888 | SWOG S0221 |

Paclitaxel

(variable schedule/dose): Adjuvant- predefined number of cycles |

CTC

v.3.0 peripheral neuropathy - Grade 0-2 (controls) vs. Grade 3- 4 (cases) |

Candidate BRCA1 and FANCD2 |

FANCD2 | None |

| Leandro- Garcia(6) |

214 | Prospective Cohort |

Paclitaxel at variable dose +/− carboplatin, gemcitabine, bevacizumab, cisplatin, cetuximab, trastuzumab, or lapatinib. Metastatic setting-variable duration. |

CTC v.

2.0 peripheral neuropathy - Grade 2-3 (Cases vs. Grade 0-1 (controls) |

Candidate SNPs in Beta- tubulin IIa |

Beta-tubulin IIa |

None |

| Hertz(5) | 111 | Retrospective cohort |

Paclitaxel containing regimens- variable schedule and dose +/− cyclophosphamide or trastuzumab. Neoaduvant- predefined duration but variable |

CTC v.

4.0 peripheral neuropathy Grade 3+ (cases) |

Candidate metabolism SNPs: CYP1B1*3, CYP2C8*3, CYP3A4*1B/ CYP3A5*3C, and ABCB1*2. |

CYP2C8*3 | None |

| Baldwin( 4) |

855 | CALGB- 40101 |

Paclitaxel

4-6 cycles: Randomized, phase III trial with planned number of cycles |

CTC v.

2.0 Grade peripheral neuropathy Grade 2+ (cases) |

GWAS |

FDG4

EPHA5 FZD3 |

European American cohort (n- 154) and African American Cohort (n=117): FDG4 significant in EA (p=0.013) and AA subgroup; p=6.7 ×10−3 |

| Leandro- Garcia(8) |

144 | Prospective cohort |

Paclitaxel

+ carboplatin: variable Metastatic: duration variable and some with prior neurotoxic chemo |

CTC v.

2.0 Grade peripheral neuropathy Grade 2+ (cases) |

GWAS | EPHA4 | No validation but EPHA5 with significant p-value in meta- analysis with CALGB40101. (4) |

| Beutler(9 ) |

119 | Alliance N08C1 |

Paclitaxel at variable dose and schedule +/− carboplatin |

CIPN20 | Targeted sequencing of 49 candidate genes |

ARHGEF10 | None |

| Abraham (10) |

1303 | tAnGo & NeotAnGo |

Paclitaxel at uniform dose, but variable schedule |

CTC v.2.0 | Genotyping 73 SNPs in 50 candidate genes |

ABCB1

TUBB2A |

GWAS pending |

| Apellaniz -Ruiz (11) |

8 | Patients selected from hospital population |

Paclitaxel at variable dose and schedule |

CTC v.4.0 | Whole exome sequencing |

CYP3A4 | Yes |

| Boso (12) |

113 | Patients selected from electronic medical records |

Paclitaxel & Docetaxel |

CTC v.4.0 | Genotyping 47 SNPs in 20 candidate genes |

CYP3A4

ERCC1 CYP2C8 |

None |

| Schneider (Current study) |

1357 (for Grade 2+ analysis) 962 for Grade 3+ analysis |

ECOG- 5103 |

Paclitaxel at uniform dose and schedule. Randomized, phase III trial with predefined number of cycles +/− bevacizumab |

CTC v.

3.0 peripheral neuropathy. Grade 2+ and Grade 3+ |

GWAS |

See results section |

ECOG 1199 randomized phase III trial with paclitaxel or docetaxel at variable schedule and dose. Grade 3+ n=488. rs3125923 p=5.9×10−3 |

While each of the prior data sets has identified provocative genomic associations with TIPN, there has been little to no overlap to date by independent groups. The top two SNPs from ECOG-1199 were not reported in prior studies.(4, 8) Additionally, our study did not provide support for the previously identified SNPs as outlined in Table 2.(4-9) There have been signals, however, of potentially important susceptibility pathways. Perhaps the most provocative associations to date have been in the EPHA family of genes, although clearly not reproducible across all studies. As Wntless (this study) and Frizzled (FZD3; CALGB40101 study (4)) are in the same pathway, our validated SNP may support the importance of the Wnt pathway in TIPN.

The possible reasons for lack of complete overlap in results are multi-fold. First, some or all of these findings may be spurious. Second, the variable phenotype definition, taxane type/schedule, collection methodology, definition of race, and genomic strategy may have hampered reproducibility. The need to harmonize some of these confounding variables may be a reasonable expectation based on the underlying biology and pharmacology. For example, while the host tissue may broadly predispose a patient to a given drug or drug class that can cause neuropathy, there are biological and pharmacokinetic differences, that may make the identification of a universal predictive biomarker impossible to identify. The need to correct for all confounders, however, makes it difficult to use the marker in practice and begs the question as to which may be most valuable; a marker that is accurate for a very specific situation or a more generalizable marker with less statistical power. Regardless, novel genetic findings have the potential to unravel the underlying cause and potentially provide insight leading to novel drugs to prevent or treat TIPN. While our top SNP increased the risk, others with more modest associations decreased the risk. This speaks to the potential genetic complexity of predisposition for TIPN and also explains what is seen clinically, with some patients experiencing early and severe neuropathy while others never experience neuropathy. Multi-genetic models will ultimately need to be developed but will require multiple massive data sets for operative statistical power. Given the discordance in the data, it is highly likely that the most efficient and statistically well-poised approach will include a meta-analysis across several of these large datasets. Also, use of more high-throughput technology, such as massively parallel sequencing might further shed light on the genetic contributions.(9)

The strengths of the current study include the non-biased evaluation of common variants across the genome in a discovery cohort from a large, adjuvant randomized phase III trial with attempted validation in a similarly sized and designed trial. Despite the lack of established functionality of the SNPs identified, this represents the highest level of clinical association for a biomarker.(26) One weakness of this study includes the use of FFPE tumor derived DNA in ECOG-1199. Thus, for ECOG-1199, genotypes might be impacted by somatic point mutations and loss of heterozygosity (LOH). This limitation was minimized by careful quality review of the genotypes including filtering of SNPs that did not meet stringent criteria for the rate of genotype calls, expected MAF, and deviation from HWE. Additionally, none of these sites represent areas of frequent LOH nor somatic mutations in breast cancer.(27) Thus, while isolated cases of LOH or mutations cannot be ruled out at the individual level, at the trial level this did not appear to be an issue. Although race and obesity were significant independent predictors of peripheral neuropathy, other potentially important variables such as Diabetes Mellitus could also play a role. Unfortunately comorbidities and co-medications were not formally collected in either ECOG-5103 or ECOG-1199 and the inability to include them in modeling is a limitation to this study. Another limitation is the use of CTCAE phenotype definitions. Recent work has demonstrated patient reported outcomes (PROs) might be more sensitive.(28) The use of PROs in large trials is beginning to be used to help enhance clinically relevant interpretation and is destined to augment correlative studies such as these. Finally, although ECOG-5103 and ECOG-1199 were similar in design and size, there were some important differences. Important to this correlative work was the variability in taxane implemented and schedule. SNPs that might be docetaxel-specific would not have been identified from the discovery cohort that included only paclitaxel. Further, confirmation of paclitaxel-specific SNPs may have been underpowered in the validation cohort where only half the patients received paclitaxel. As we set out on this project, however, our hope was to identify a marker(s) that would predispose to neuropathy from the taxanes broadly.

In the group genome-wide genotyped from ECOG-5103, there was also a substantial increase in the risk for TIPN in AA patients. Further, the degree of African American ancestry (determined by PC1; with higher values representing less African ancestry) was even more statistically significant than the binary analysis. For example, the hazard ratio of 0.5 seen in the Grade 2-4 analysis meant that a 1-unit change in PC1 (reflecting a decrease in African ancestry) reduced the neuropathy risk by 50%. This analysis further supports that this is a true genetic effect, rather than environmental. Based on these data, AA patients should also be counseled about the increased risk of TIPN. As previously described, self-defined race is often inaccurate and thus ECOG-5103 includes a truly unique cohort of genetically defined AA patients from a trial with rigorous uniformity for phenotype collection. The GWAS confined to AA patients did identify an interesting group of SNPs that associated with TIPN on Chromosome 1, including rs1856746. This SNP, found at 1q32.2, is located within 20 Kb of FCAMR, a gene that encodes for the Fc receptor Fcα/μR. Fcα/μR is found in B Cells and lymphoid cells and is highly specific for IgM and IgA.(29) Though the mechanism of action for TIPN is not fully understood, there is evidence of a possible relationship with the immune system.(30) The rs1856746 G allele is more common in AA than EA (96% vs. 44%) and may partially explain the differential genetic predisposition. Although intriguing, this finding should only be regarded as hypothesis generating. Because of the substantial risk for TIPN in the AA cohort, additional work from other large data sets is warranted to confirm or refute these findings.

As markers of other toxicities from competing regimens emerge, more personalized treatment regimens can be recommended. The ultimate goal, however, is to identify therapies that might treat or prevent these toxicities. The genetic findings for predisposition might serve nicely to help unravel the mechanistic underpinnings, an important first step in therapeutic development and improved patient care.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

The optimal therapeutic index for any given drug is a function of efficacy as well as toxicity. While much work has focused on the identification of biomarkers that predict efficacy, the discovery of high quality biomarkers that predict toxicity are lacking. Inherited genetic variation is one important source for the heterogeneity in toxicity seen across a population. Drug-induced side effects can create unnecessary, serious medical morbidity and can impact the global quality of life experience for the patient. A significant toxicity can also limit the full-intended receipt of a potentially life-saving therapy. Taxane induced peripheral neuropathy is one of the most common and important toxicities across multiple disease types and settings. Herein we demonstrate that African American Race and a genetic variant (rs3125923) are important predictors for this toxicity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Biospecimens were provided by the ECOG Pathology Coordinating Office and Reference Laboratory.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: This study was coordinated by ECOG Group (RL Comis) and supported by NIH/NCI grants CA23318, CA66636, CA21115, CA49883, CA14958, CA16116, CA39229, CA25224, CA12027, CA32102, CA20319, CA77202; Susan G. Komen for the Cure; Conquer Cancer Foundation (BP Schneider); and Breast Cancer Research Foundation (D Hayes). Its content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NCI.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT:

The following authors have received research funds from Genentech/Roach: Kathy D. Miller, Mary Lou Smith and Elda Railey; from Novatis and Amgen: Mary Lou Smith and Elda Railey; and from Lilly, Celgene, Morphotek and Sanofi: Mary Lou Smith and Elda Railey. Bryan P. Schneider is on the advisory board of Genentech (compensated). Kathy D. Miller has received honoraria from Genentech. Joseph A. Sparano has received consulting fees from Genentech.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghersi D, Wilcken N, Simes RJ. A systematic review of taxane-containing regimens for metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:293–301. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nowak AK, Wilcken NR, Stockler MR, Hamilton A, Ghersi D. Systematic review of taxane-containing versus non-taxane-containing regimens for adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment of early breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:372–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park SB, Goldstein D, Krishnan AV, Lin CS, Friedlander ML, Cassidy J, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: a critical analysis. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:419–37. doi: 10.3322/caac.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin RM, Owzar K, Zembutsu H, Chhibber A, Kubo M, Jiang C, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel loci for paclitaxel-induced sensory peripheral neuropathy in CALGB 40101. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5099–109. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hertz DL, Motsinger-Reif AA, Drobish A, Winham SJ, McLeod HL, Carey LA, et al. CYP2C8*3 predicts benefit/risk profile in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant paclitaxel. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2012;134:401–10. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2054-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leandro-Garcia LJ, Leskela S, Jara C, Green H, Avall-Lundqvist E, Wheeler HE, et al. Regulatory polymorphisms in beta-tubulin IIa are associated with paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4441–48. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sucheston LE, Zhao H, Yao S, Zirpoli G, Liu S, Barlow WE, et al. Genetic predictors of taxane-induced neurotoxicity in a SWOG phase III intergroup adjuvant breast cancer treatment trial (S0221). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:993–1002. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1671-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leandro-Garcia LJ, Inglada-Perez L, Pita G, Hjerpe E, Leskela S, Jara C, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies ephrin type A receptors implicated in paclitaxel induced peripheral sensory neuropathy. J Med Genet. 2013;50:599–605. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beutler AS, Kulkarni AA, Kanwar R, Klein CJ, Therneau TM, Qin R, et al. Sequencing of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease genes in a toxic polyneuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:727–37. doi: 10.1002/ana.24265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abraham JE, Guo Q, Dorling L, Tyrer J, Ingle S, Hardy R, et al. Replication of genetic polymorphisms reported to be associated with taxane-related sensory neuropathy in patients with early breast cancer treated with Paclitaxel. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014;20:2466–75. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apellaniz-Ruiz M, Lee MY, Sanchez-Barroso L, Gutierrez-Gutierrez G, Calvo I, Garcia-Estevez L, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals defective CYP3A4 variants predictive of paclitaxel dose-limiting neuropathy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2015;21:322–28. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boso V, Herrero MJ, Santaballa A, Palomar L, Megias JE, de la Cueva H, et al. SNPs and taxane toxicity in breast cancer patients. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15:1845–58. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller K, O'Neill AM, Dang CT, Northfelt DW, Gradishar WJ, Goldstein LJ, et al. Bevacizumab (Bv) in the adjuvant treatment of HER2-negative breast cancer: Final results from Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group E5103. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl) abstr 500. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sparano JA, Wang M, Martino S, Jones V, Perez EA, Saphner T, et al. Weekly paclitaxel in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1663–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider BP, Li L, Shen F, Miller KD, Radovich M, O'Neill A, et al. Genetic variant predicts bevacizumab-induced hypertension in ECOG-5103 and ECOG-2100. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1241–48. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. https://mathgen.stats.ox.ac.uk/genetics_software/snptest/snptest.html.

- 17.Barsh GS, Copenhaver GP, Gibson G, Williams SM. Guidelines for genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider BP, Zhao F, Wang M, Stearns V, Martino S, Jones V, et al. Neuropathy is not associated with clinical outcomes in patients receiving adjuvant taxane-containing therapy for operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3051–57. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, Lavoie Smith EM, Bleeker J, Cavaletti G, et al. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1941–67. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manchia M, Cullis J, Turecki G, Rouleau GA, Uher R, Alda M. The impact of phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity on results of genome wide association studies of complex diseases. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baak-Pablo R, Dezentje V, Guchelaar HJ, van der Straaten T. Genotyping of DNA samples isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues using preamplification. J Mol Diagn. 2010;12:746–49. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.100047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Bailey SD, Lupien M. Laying a solid foundation for Manhattan--'setting the functional basis for the post-GWAS era'. Trends Genet. 2014;30:140–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fehrmann RS, Jansen RC, Veldink JH, Westra HJ, Arends D, Bonder MJ, et al. Trans-eQTLs reveal that independent genetic variants associated with a complex phenotype converge on intermediate genes, with a major role for the HLA. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciani L, Salinas PC. WNTs in the vertebrate nervous system: from patterning to neuronal connectivity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:351–62. doi: 10.1038/nrn1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simonetti M, Agarwal N, Stosser S, Bali KK, Karaulanov E, Kamble R, et al. Wnt-Fzd signaling sensitizes peripheral sensory neurons via distinct noncanonical pathways. Neuron. 2014;83:104–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM, et al. REporting recommendations for tumor MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:229–35. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtis C, Shah SP, Chin SF, Turashvili G, Rueda OM, Dunning MJ, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012;486:346–52. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hershman DL, Weimer LH, Wang A, Kranwinkel G, Brafman L, Fuentes D, et al. Association between patient reported outcomes and quantitative sensory tests for measuring long-term neurotoxicity in breast cancer survivors treated with adjuvant paclitaxel chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:767–74. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouchida R, Mori H, Hase K, Takatsu H, Kurosaki T, Tokuhisa T, et al. Critical role of the IgM Fc receptor in IgM homeostasis, B-cell survival, and humoral immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2699–706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210706109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stork AC, van der Pol WL, Franssen H, Jacobs BC, Notermans NC. Clinical phenotype of patients with neuropathy associated with monoclonal gammopathy: a comparative study and a review of the literature. J Neurol. 2014;261:1398–404. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.