Abstract

Background

Mounting evidence suggests a causal relationship between specific bacterial infections and the development of certain malignancies. However, the possible role of the keystone periodontal pathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis, in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) remains unknown. Therefore, we examined the presence of P. gingivalis in esophageal mucosa, and the relationship between P. gingivalis infection and the diagnosis and prognosis of ESCC.

Methods

The presence of P. gingivalis in the esophageal tissues from ESCC patients and normal controls was examined by immunohistochemistry using antibodies targeting whole bacteria and its unique secreted protease, the gingipain Kgp. qRT-PCR was used as a confirmatory approach to detect P. gingivalis 16S rDNA. Clinicopathologic characteristics were collected to analyze the relationship between P. gingivalis infection and development of ESCC.

Results

P. gingivalis was detected immunohistochemically in 61 % of cancerous tissues, 12 % of adjacent tissues and was undetected in normal esophageal mucosa. A similar distribution of lysine-specific gingipain, a catalytic endoprotease uniquely secreted by P. gingivalis, and P. gingivalis 16S rDNA was also observed. Moreover, statistic correlations showed P. gingivalis infection was positively associated with multiple clinicopathologic characteristics, including differentiation status, metastasis, and overall survival rate.

Conclusion

These findings demonstrate for the first time that P. gingivalis infects the epithelium of the esophagus of ESCC patients, establish an association between infection with P. gingivalis and the progression of ESCC, and suggest P. gingivalis infection could be a biomarker for this disease. More importantly, these data, if confirmed, indicate that eradication of a common oral pathogen could potentially contribute to a reduction in the overall ESCC burden.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13027-016-0049-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Porphyromonas gingivalis, ESCC, Lys-gingipain, 16S rDNA, Oral pathogen, Differentiation, Metastasis, Overall survival rate, Prognoses

Background

Since the discovery that Helicobacter pylori plays a causative role in gastric adenocarcinoma, multiple other associations between specific bacteria and cancer have been reported [1, 2], including Salmonella typhi with gall bladder cancer [3], Streptococcus bovis with colon cancer [4], Chlamydophila penumoniae with lung cancer [5], Bartonella species with vascular tumor formation [6], Propionibacterium acnes with prostate cancer [7], and Escherichia coli with colon cancer [8]. Esophageal cancer is the eighth most frequent tumor and sixth leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Whereas the majority of cases occur in Asia, particularly in central China, recent data suggest that the frequency of new cases is rising in Western Europe and the USA [9, 10]. Two major histological subtypes of esophageal cancer have been identified including squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), which is more common in developing countries, and adenocarcinoma, which is more common in developed nations [11]. Esophageal cancer is characterized by difficulty of early diagnosis, rapid development and high mortality. Therefore, there is a considerable need to better understand causative agents in order to reduce the incidence and mortality of this disease. Like most cancers, a plethora of risk factors including age, gender, heredity, gene mutation, chemical exposure, and diet have been reported for esophageal cancer [12, 13].

A potential contribution of microbes to the development of esophageal cancer is beginning to emerge. Pei et al. reported that Streptococcus, Prevotella and Veillonella are the most prevalent genera detected in esophageal biopsies [14, 15]. Yang et al. have classified the esophageal microbiota into two subtypes: the Streptococcus-dominated type I microbiome, which is mainly associated with a normal esophagus, and the type II microbiome, in which Gram-negative anaerobes predominate, which is associated with Barrett’s esophagus (BE) and esophagitis [16]. A significant association between the inhabitants of the upper digestive tract microbiota and esophageal squamous dysplasia, a precursor lesion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, has also been reported [17]. While there are several phylum-wide studies on the esophageal microbiota and the possible associations with reflux esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal squamous dysplasia, there has been no research on the esophageal microbiota in patients suffering from ESCC, especially at species level, let alone the possible association of these bacteria with the development of ESCC.

The microbiome in chronic and severe manifestations of periodontal disease is enriched for Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. Among these, Porphyromonas gingivalis is a keystone oral pathogen which can invade epithelial cells, and interfere with host immune responses and the cell cycle machinery [18–20]. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that periodontal diseases and tooth loss are significantly associated several cancers such as oral cancer, gastric cancer, and pancreatic cancer and may even relate to survival [20–24]. P. gingivalis-mediated immune evasion, apoptosis inhibition, carcinogen conversion, induction of MMP-9 and dysbiosis of the oral microbiota have all been posited as pro-tumorigenic mechanisms in the context of oral squamous cell carcinoma [20, 25]. Since esophageal squamous cells are histologically similar to oral squamous cells and esophageal infection arising from the oral niche is highly plausible, we hypothesized that P. gingivalis may be associated with ESCC. We set out to test this hypothesis using 100 ESCC subjects and 30 normal matched controls.

Results

Immunohistochemical detection of P. gingivalis presence is more common in ESCC

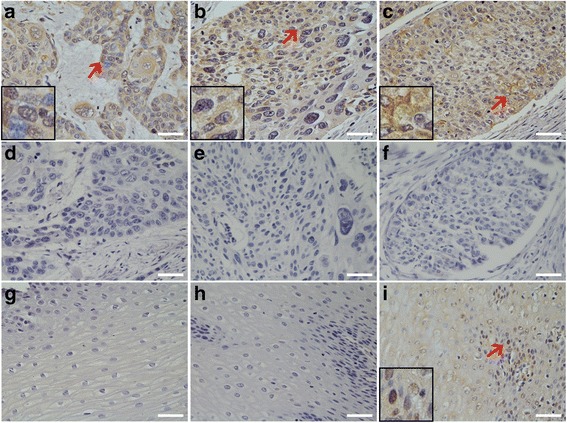

As shown in Fig. 1, P. gingivalis was detected in cancerous and adjacent esophageal mucosa, but not healthy mucosa. Furthermore, P. gingivalis infection was more common in cancerous tissue (61 %) than adjacent tissue (12 %) or normal control tissue (0 %) (both p < 0.01, Table 1). P. gingivalis was primarily immunolocalized to the epithelial cell cytoplasm but bacterial antigens were occasionally present in nuclei.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical detection of P. gingivalis in normal esophageal mucosa, and cancerous and adjacent tissues of ESCC. a, b, and c are representative images of P. gingivalis in well differentiated (a), moderately differentiated (b), and poorly differentiated (c) ESCC tissues. Pre-immune rabbit IgG was used as a control to detect the serial tissue sections from the same paraffin-embedded tissue block of: (d) well differentiated-; (e) moderately differentiated-; and (f) poor differentiated ESCC. g Normal esophageal mucosa stained with anti-P. gingivalis anti-serum; (h) and (i) are the representative negative/positive images of P. gingivalis immunostaining in the adjacent cancerous tissues. 20× magnification; scale bar = 50 μm; miniatures in the left corners amplify the area with red arrows

Table 1.

Presence of P. gingivalis and Lys-gingipain (Kgp) detected by specific antibodies in normal esophagus mucosa, cancerous and adjacent tissues of ESCC

| Factors | Pg positive cases (%) | KGP positive cases (%) |

|---|---|---|

| ESCC samples (n = 100) | 61 (61)* | 66 (66)* |

| Adjacent normal tissues (n = 100) | 12 (12)* | 17 (17)* |

| Normal esophageal mucosa (n = 30) | 0 (0)* | 0 (0)* |

*p < 0.01

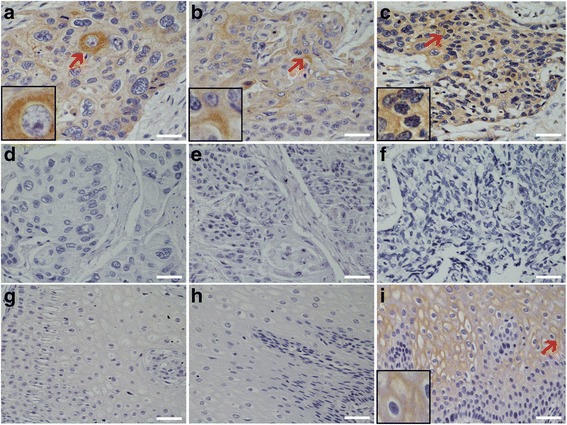

Expression of P. gingivalis lysine-gingipain (Kgp) is more common in ESCC

To corroborate the presence of P. gingivalis antigens in esophageal epithelium, we next used a Kgp-specific antibody. As shown in Fig. 2, the expression pattern of Kgp reflected that of the whole cell antigens as above, being primarily expressed in the epithelial cytoplasm but occasionally in nuclei, and expressed at significantly high levels in cancerous tissue (66 %), as compared with adjacent (17 %) or healthy tissues (0 %) (both p < 0.01, Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical detection of Lys-gingipain (Kgp) in normal esophagus mucosa, cancerous and adjacent tissues of ESCC. a, b, and c are representative images of Lys-gingipain in well differentiated (a), moderately differentiated (b), and poorly differentiated (c) ESCC tissues. Normal mouse IgG was used as a control to detect the serial tissue sections from the same paraffin-embedded tissue block of (d) well differentiated-; (e) moderately differentiated-; and (f) poorly differentiated ESCC. g Normal esophageal mucosa stained with anti-Lys-gingipain antibody; (h) and (i) are the representative negative/positive images of Lys-gingipain immunostaining in the adjacent cancerous tissues. 20× magnification; scale bar = 50 μm; miniatures in the left corners amplify the area with red arrows

P. gingivalis 16S rDNA is more frequent in ESCC

To control for false positives due to possible cross-reaction of antibodies, we next employed qRT-PCR to examine the presence of 16S rDNA in fresh esophageal tissue specimens. All esophageal samples were positive for the presence of bacteria, as determined using universal 16S rDNA primers (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Similar to the staining pattern with antibodies to the whole cells and to Kgp, P. gingivalis 16S rDNA was present in significantly more frequently in the cancerous tissues (71 %) than adjacent (12 %) or normal esophagus mucosa (3.3 %; both p < 0.001), as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

PCR-detected expression of P. gingivalis in normal esophagus mucosa, cancerous and adjacent tissues of ESCC

| Factors | Positive (%) | Negative (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESCC samples (n = 100) | 71 (71) | 29 (29) | <0.0001 |

| Adjacent normal tissue (n = 100) | 12 (12) | 88 (88) | |

| Normal esophageal mucosa (n = 30) | 1 (3.3) | 29 (96.7) |

Comparison of different methods for the detection of P. gingivalis presence

We next analyzed the correlation between the expression of P. gingivalis whole antigens and Kgp, and the concordance between the results of immunohistochemistry (IHC) and real time qPCR. Of the 100 esophageal cancerous tissue specimens that were analyzed in this study, 59 % of samples were positive for immunohistochemical staining for both P. gingivalis cells and Kgp enzyme (Table 3). The level of P. gingivalis whole cell staining was found to significantly correlate with the level of the Kgp staining in cancerous tissue of ESCC patients (p <0.0001; Pearson’s contingency coefficient = 0.630). Moreover, we compared the results of IHC and qRT-PCR for the presence of P. gingivalis to determine the agreement between these two different methods. The data showed that the average percentage of cancerous tissues positively stained with anti-P. gingivalis antibody in the qRT-PCR positive tumors was significantly higher than in the qRT-PCR negative tumors (84.5 % versus 3.4 %; p <0.0001). There was only one case with IHC scores of 2 that was qRT-PCR negative. However, we found eleven cases with IHC scores of lower than 2 that were qRT-PCR positive (Table 4), suggesting our IHC standard is higher and qRT-PCR is more sensitive for the detection of P. gingivalis in cancerous tissue. In current study, IHC scores with whole P. gingivalis antigen equal or more than 2 were P. gingivalis-positive. The sensitivity and specificity of IHC were 84.5 and 96.6 %, respectively. The concordance rate was 88 % (kappa = 0.736; p < 0.001) between IHC and qRT-PCR (Table 4). When we re-examined the eleven cases which were IHC negative and qRT-PCR positive, we found 7 of them staining with an IHC score close to 2, suggesting the positive criteria of IHC is critical for the agreement of these two methods. If we set the samples with IHC scores more than 1 as P. gingivalis positive, the sensitivity and specificity of IHC would be 94.3 and 96.6 %, respectively (Kappa = 0.882; p < 0.001, Additional file 2: Table S1), showing excellence concordance between IHC and qRT-PCR for the detection of P. gingivalis infection in the cancerous tissues of ESCC patients.

Table 3.

Pearson’s contingency coefficient analysis of the correlation between the levels of immunohistochemical staining of P. gingivalis and KGP in cancerous tissue of ESCC patients

| Antigens | KGP expression | R value | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | - | |||

| Pg (+) | 59 | 2 | 0.630 | <0.0001 |

| Pg (−) | 7 | 32 | ||

| Total | 66 | 34 | ||

*Data presented as the number of patients. P < 0.0001; Pearson’s contingency coefficient =0.630

Table 4.

Concordance between the immunohistochemistry with P. gingivalis whole cell antibodies and qPCR of P. gingivalis 16S rDNA in the cancerous tissue from patients with ESCC

| Approaches | PCR expression | Kappa value | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | - | |||

| IHC (+) | 60 | 1 | 0.736 | <0.0001 |

| IHC (−) | 11 | 28 | ||

| Total | 71 | 29 | ||

*Kappa value >0.7 excellent; 0.4–0.7, good; <0.4, poor agreement

P. gingivalis infection is positively correlated to clinicopathologic characteristics of ESCC

Since an association between P. gingivalis infection and ESCC had been demonstrated, we next sought to determine if the presence of P. gingivalis antigens is associated with the progression of esophageal cancer. Pathological information of the ESCC patients is presented in Table 5. While the presence of P. gingivalis was not significantly associated with age, gender, or smoking history of the patients, the presence of P. gingivalis was positively related to differentiation, lymph node metastasis and the TNM stage of ESCC (p < 0.05). A positive immunohistochemical signal for P. gingivalis was 90 % in the poorly differentiated tissues, which was significantly higher than that of well or moderately differentiated samples (p < 0.05) (Table 5). Moreover, the percentage of P. gingivalis infected lymph node metastasis samples was 84.2 %, statistically higher than that of non-metastatic group (46.8 %; p < 0.05) (Table 5). Similar relationships between P. gingivalis-derived Kgp expression, cancer cell differentiation and metastasis were observed (Table 5). Additionally, the presence of P. gingivalis was closely related to the TNM stage of ESCC. Late stage ESCC tissues were more likely to be positive for whole P. gingivalis-derived antigens (87.5 %) or Kgp (84.4 %) than early stage ESCC (48.5 and 57.4 %, respectively; p < 0.05). Taken together, these results reveal that P. gingivalis infection is positively correlated with poor differentiation, severe lymph node metastasis and stage of ESCC, suggesting that P. gingivalis could be a novel etiologic agent and potential prognostic indicator of this important malignant disease.

Table 5.

Association between the presence of P. gingivalis or Lys-gingipain and the clinicopathologic features of ESCC patients

| Factors | Pg positive cases (%) | KGP positive cases (%) |

|---|---|---|

| ESCC samples (n = 100) | 61(61)** | 66(66)** |

| Adjacent normal tissues (n = 100) | 12(12)** | 17(17)** |

| Normal esophageal mucosa (n = 30) | 0(0)** | 0(0)** |

| Gender | ||

| Male (n = 70) | 45(64.3) | 48(68.6) |

| Female (n = 30) | 16(53.3) | 18(60.0) |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤60 (n = 39) | 24(61.5) | 23(59.0) |

| >60 (n = 61) | 37(60.7) | 43(70.5) |

| Smoking history | ||

| Smoking (n = 45) | 31(68.9) | 32(71.1) |

| Non-smoking (n = 55) | 30(54.5) | 34(61.8) |

| Differentiation | ||

| Well (n = 22) | 8(36.4)* | 10(45.5)* |

| Moderate (n = 58) | 35(60.3)* | 39(67.2)* |

| Poor (n = 20) | 18(90.0)* | 17(85.0)* |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||

| Positive (n = 38) | 32(84.2)* | 31(81.6)* |

| Negative (n = 62) | 29(46.8)* | 35(56.5)* |

| TNM stage | ||

| I+ II (n = 68) | 33(48.5)* | 39(57.4)* |

| III (n = 32) | 28(87.5)* | 27 (84.4)* |

“**”and “*”indicate p < 0.01 and p <0.05, respectively

P. gingivalis infection is negatively correlated with overall ESCC survive rate

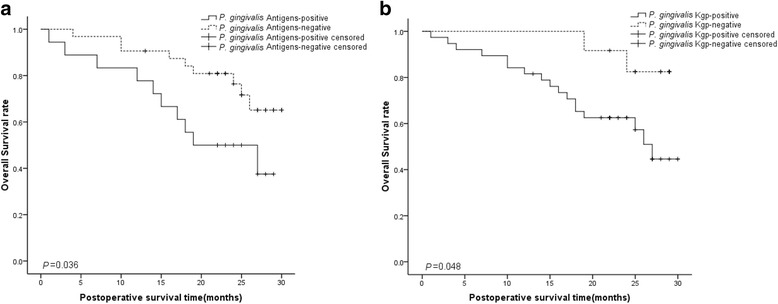

In order to assess the potential consequences of P. gingivalis infection on ESCC patients, we next compared the overall cumulative survival rate in ESCC patients with and without P. gingivalis infection. A total of 100 patients were followed up for survival analysis over a period of 30 months (Table 6). Because of the limited follow-up time, the survival rate of both groups was greater than 40 % and the median survival time could not be calculated. However, the mean survival time for patients with positive P. gingivalis antigen expression was 20.139 months, significantly lower than that of P. gingivalis negative group (25.971 months) or all patients (23.981 months) (both p < 0.05) (Table 6). Similar results were found when Lys- gingipain expression were examined, with mean survival times of 22.475, 27.078, and 23.981 months for positive, negative and all patients group, respectively (6). Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the difference between negative and positive P. gingivalis presence was significant for overall survival both for P. gingivalis positive staining (n = 100, p = 0.036) (Fig. 3a) and Kgp positive expression (n = 100, p = 0.048) (Fig. 3b).

Table 6.

Means and medians for the survival time (months) of ESCC patients with positive or negative expression of P. gingivalis and Lys-gingipain

| Factors | Group | Meana | Mediana | p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95 % Confidence interval | ||||||||||

| Est. | Std. error | Lower bound | Upper bound | Est. | Std. error | Lower bound | Upper bound | |||

| Pg | Positive | 20.139 | 2.238 | 15.752 | 24.526 | 19.000 | 5.874 | |||

| Negative | 25.971 | 1.264 | 23.493 | 28.449 | ||||||

| Overall | 23.981 | 1.225 | 21.580 | 26.382 | 0.036 | |||||

| KGP | Positive | 22.475 | 1.507 | 19.521 | 25.430 | 27.000 | 1.648 | 23.770 | 30.230 | |

| Negative | 27.708 | 0.874 | 25.996 | 29.421 | ||||||

| Overall | 23.981 | 1.225 | 21.580 | 26.382 | 0.048 | |||||

aEstimation is limited to the largest survival time; “Est.” and “Std.” are the abbreviations of “estimated” and “standard” respectively

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis of the relationship between the presence of P. gingivalis and the expression of Lys-gingipain and the overall survival rate of ESCC patients. Higher expression of the P. gingivalis whole cell antigens (a) or Lys-gingipain (b) were both positively related with poorer overall survival rate of ESCC patients. The p value is 0.036 (a) and 0.048 (b) respectively

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the composition and potential role of the esophageal microbiota in the patients suffering from ESCC have not been investigated. Using three complementary approaches, we have established that antigens and DNA from P. gingivalis, a periodontal pathogen, can be detected in the epithelium of the esophagus of ESCC patients. The intensity of expression of whole P. gingivalis antigen, its unique protease Lys-gingipain, and detection of P. gingivalis-specific16S rDNA were all significantly higher in the cancerous tissue of ESCC patients than in the surrounding tissue or normal control sites. Moreover, our analysis indicates that the presence of P. gingivalis correlates with multiple clinicopathologic factors, including cancer cell differentiation, metastasis, and overall survival ESCC rate. These findings provide the first direct evidence that P. gingivalis infection could be a novel risk factor for ESCC, and may also serve as a prognostic biomarker for this prevalent cancer.

A number of aspects of the interaction of P. gingivalis with host epithelial cells provide a plausible molecular basis for potential P. gingivalis-mediated carcinogenesis [20, 25, 26]. First, chronic inflammation per se is associated with the development of cancer [27], and, for example, prolonged IL-6 signaling and STAT3 activity is known to be pro-tumorogenic [28, 29]. In this regard, both our group and others have demonstrated that P. gingivalis activates JAK2 and GSK3β pathways, thus increasing the production of IL-6 in epithelial cells [28, 30]. Secondly, P. gingivalis can promote tumorigenesis by secreting a nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK). NDK from P. gingivalis antagonizes ATP activation of P2X7 receptors, and thus reduces IL-1β production from epithelial cells [31]. Since IL-1β is critical for priming IFNγ-producing, tumor–antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, NDK from P. gingivalis could promote the immune evasion of tumor cells [20]. Moreover, NDK-mediated degradation of ATP also suppresses apoptosis dependent on ATP activation of P2X7 receptors [32]. Thirdly, P. gingivalis inhibits epithelial cell apoptosis by a number of mechanisms, including activation of Jak1/Akt/Stat3 [33, 34], enhancing the Bcl2 (antiapoptotic): Bax (proapoptotic) ratio, blocking the release of the apoptosis effector cytochrome c, and the activation of downstream caspases [35]. Moreover, P. gingivalis can upregulate microRNAs, such as miR-203, which suppress apoptosis in primary gingival epithelial cells [36]. In concert with suppression of apoptosis, P. gingivalis can accelerate progression through the cell cycle by manipulation of cyclin/CDK (cyclin-dependent kinase) activity and reducing the level of the p53 tumor suppressor [37]. Lastly, in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells, P. gingivalis promotes cellular migration through activation of the ERK1/2-Ets1, p38/HSP27, and PAR2/NF-κB pathways to induce pro-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression [25]. Apart from all the above, another possible mechanism for P. gingivalis induced carcinogenesis is the metabolism of potentially carcinogenic substances. For example, P. gingivalis converts ethanol into its carcinogenic derivative, acetaldehyde, to levels capable of inducing DNA damage, mutagenesis and hyperproliferation of the epithelium [38, 39], which could help explain the epidemiological evidence associating heavy drinking and development of some cancers [20].

While it is possible that P. gingivalis infection initiates or is a co-factor in the transformation of esophageal epithelial cells, the possibility that cancer tissues represent a preferred microenvironment for P. gingivalis cannot be excluded. Thus, while our results reveal a positive association between infection with P. gingivalis and the progression of ESCC, P. gingivalis is not yet established as a novel etiological agent or co-factor of ESCC. Should P. gingivalis prove to cause ESCC, the implications are enormous. It would suggest (i) that improved oral hygiene might reduce ESCC risk, (ii) that screening for P. gingivalis in dental plaque may identify susceptible subjects, and that (iii) antibiotic use, or other anti-bacterial strategies, may prevent ESCC progression. Should the clear association between P. gingivalis infection and ESCC turn out to be better explained by physiological conditions inside ESCC cells being more amenable to P. gingivalis survival and growth, this would imply that attenuated P. gingivalis or non-pathogenic bacteroidetes strains that contain eukaryotic lysins may represent a novel and effective therapeutic approach for ESCC. In this regard, several studies have attempted to take advantage of the oxygen-limited conditions present in malignant cells to develop anaerobic, non-pathogenic bacteria for the delivery of cancer cell cytolysins [40]. These include Clostridium novyi for the treatment of melanoma and modified Bifidobacterium longum carrying 5-fluorocytosine for the treatment of breast cancer [41–43]. Hence, further studies to determine if P. gingivalis infection promotes the initiation and progression of ESCC are required.

Finally, colonization by P. gingivalis promotes the conversion of a symbiotic to a dysbiotic of oral microbiota, a process considered critical for the progression of periodontal disease [44]. Dysbiosis of the microbiota in the esophagus could potentially cause or exacerbate the severity of esophageal disorders [18]. Thus, a further possibility to be tested is that esophageal infection with P. gingivalis leads to shift in the microbiome involved in the development of esophageal cancer.

Conclusion

In summary, we have established that P. gingivalis molecules are present in the epithelium of the esophagus of ESCC patients and provide the first direct evidence of a positive correlation between P. gingivalis infection, ESCC severity and poor prognosis. These findings demonstrate for the first time that P. gingivalis infects the epithelium of the esophagus of ESCC patients, establish the association between the infection of P. gingivalis and the progression of ESCC, and suggest P. gingivalis infection could be a biomarker for this disease. More importantly, these data, if confirmed, indicate that eradication of an oral pathogen could potentially contribute to a reduction in the overall ESCC burden.

Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Henan University of Science and Technology (HUST).

Patients and human tissue

One hundred patients with ESCC who underwent esophagectomy surgery from 2010 to 2014 at the First Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Science and Technology and Anyang people’s hospital were investigated in this study. Adjacent tissue samples were obtained 3 cm distant to cancerous tissue. Thirty additional specimens were randomly selected during endoscopic examination from biopsy, and confirmed histologically as normal esophagus mucosa. Demographics (sex and age) and clinicopathologic features (differentiation status, lymphatic invasion, lymph node metastasis, TNM stage) were obtained from medical records. A smoker was defined as someone who had smoked one cigarette or more per day for at least 1 year. Overall survival rates were determined over 30 months.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in formalin and then embedded in paraffin. Serial sections of 4 mm thickness were prepared and deparaffinized by submersion in three separate concentrations of ethanol (100, 95, and 70 %), and rinsing continuously in distilled water for 5 min. Antigen retrieval was performed by incubating slides in antigen retrieval Citra plus solution (BioGenex, San Ramon, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were blocked 1.5 % normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, USA) for 30 min. Polyclonal rabbit anti-P. gingivalis 33277 [45] and monoclonal mice anti-Lys-gingipain (Kgp) (15C8G5E6C2) antibodies [46] were utilized for the detection of P. gingivalis. Pre-immune rabbit IgG and normal mouse IgG was used as a negative control. Primary antibodies were incubated with tissue sections (anti-whole cells 1:1000 dilution; anti-Lys-gingipain 1:500 dilution) for 12 h, 4 °C, followed by biotin-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, streptavidin-peroxidase for 30 min at room temperature, and enzyme substrate (3,3′-Diaminobenzidine, Dako, Denmark). As an additional control, sections were also incubated with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) only, followed by incubation with biotin-conjugated secondary antibody, streptavidin-peroxidase, and enzyme substrate. PBS washes (3 times, 5 min each) were performed during each incubation step. Sections were counterstained with methyl green and visualized by light microscopy (Eclipse 80i, Nikon, Japan). Every tissue section was evaluated by two senior pathologists (Dr. Mi and Dr. Zhang). The kappa statistic was used to assess inter-observer variability with a score of >0.75 indicating excellent agreement. Staining intensity was classified using a numerical scale; grade 0 (none, 0–10 % staining); grade 1 (weak, 10–30 %); grade 2 (moderate, 30–60 %), and grade 3 (strong, over 60 %), with a score of > =2 considered positive of staining with P. gingivalis or Lys-gingipain.

Determination of16S rDNA in fresh ESSC tissue

For each patient, tissues from cancer and adjacent to cancer sites (minimum 3 cm distant) were harvested and used as experimental and internal controls, respectively. Endoscopy biopsy specimens from healthy age- and gender-matched individuals were obtained from normal controls (n = 30). Tissues were suspended in 500 μl of sterile phosphate-buffered saline, vortexed for 30 s and sonicated for 10 s. Proteinase K (2.5 mg/ml final concentration) was added and the samples were incubated overnight at 55 °C, homogenized with sterile disposable pestle and vortexed. DNA was extracted as described previously [47] and purified by phenol-chloroform extraction. All samples were stored at −20 °C until further analysis. For amplification, DNA concentrations were adjusted to 20 ng/ml. 16S rDNA samples were amplified as described previously [47] using P. gingivalis specific and universal 16S rDNA primers (P. gingivalis 16S rDNA primer sequences were: 5′ AGGCAGCTTGCCATACTGCG 3′ (forward) and 5′ ACTGTTAGCAACTACCGATGT 3′ (reverse), and the PCR product size was 404 bp; The universal 16S rDNA primer sequences were 5′ GATTAGATACCCTGGTAGTCCAC 3′ (forward) and 5′ CCCGGGAACGTATTCACCG 3′ (reverse), and the PCR product size was 688 bp). PCR reactions were performed at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, annealing at 52 °C for 1 min, and elongation at 72 °C for 1 min with final elongation at 72 °C for 5 min.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by SPSS statistical package, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Pearson’s contingency coefficient was used to test for the association between the immunohistochemical staining levels of P. gingivalis and Kgp. Correlations between the presence of P. gingivalis and clinicopathologic factors were analyzed by ANOVA or Chi-square test, as appropriate. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test for comparison. Multivariate analysis was performed to examine if P. gingivalis presence was an independent prognostic factor using the Cox proportional-hazards regression model. P values of ≤ 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the financial supports by Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, GS 81472234; NSFC, YX U1404817), and partially by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research at National Institutes of Health, USA, DE023633 (HW), DE017921, DE011111 (RJL), and JP acknowledges support by NIDCR/NIH DE 022597, European Commission (FP7-PEOPLE-2011-ITN-290246 “RAPID” and FP7-HEALTH-F3-2012-306029 “TRIGGER”) and Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (project 2975/7.PR/13/2014/2).

Abbreviations

- ESCC

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- BE

Barrett’s esophagus

- Kgp

Lysine-gingipain

- TNM

Tumor-node-metastasis

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- JAK2

Janus kinase 2

- GSK3β

Glycogen synthesis kinase 3 beta

- NDK

Nucleoside diphosphate kinase

- PAR

Proteinase-activated receptor

- CDK

Cyclin-dependent kinase

- MMP

Metalloproteinase

- OSCC

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

Additional files

P. gingivalis 16S DNA in esophageal epithelium. PCR with specific primers for P. gingivalis (upper), and a universal primer (lower). Representative images of P. gingivalis PCR products from several pairs of cancerous (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8) and adjacent fresh biopsy tissues from ESCC patients (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9), and normal biopsy tissues as a control (Lane 10). Lanes1 and 11 are molecular size markers. (PDF 215 kb)

Concordance between the immunohistochemistry of P. gingivalis whole antigens and RT-PCR of P. gingivalis 16S rRNA in the cancerous tissue from patients with ESCC. (PDF 43 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SG, SL, and HW contributed to the experimental studies; SG, XF and HW contributed to the study design, supervision of experiments, and manuscript review; ZM, SL, TS, MZ, XZ, PZ, GL, FZ, XY, and RJ contributed to the collection of samples, the acquisition of clinical data, and the supervision of the experiments; FZ, HW, DAS, and RJL conceived of the study and prepared the manuscript; ZM, SL, TS, MZ, XZ, PZ, GL, FZ, XY, and RJ performed surgical treatments, and patient follow-ups; JP, DAS and RJL contributed to the study design and manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Huizhi Wang, Phone: 502-852-1589, Email: huizhi.wang@louisville.edu.

Xiaoshan Feng, Phone: (086)-379-649-2362, Email: samfeng137@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.De Koster E, Buset M, Fernandes E, Deltenre M. Helicobacter pylori: the link with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1994;3:247–257. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199403030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SS, Ruiz VE, Carroll JD, Moss SF. Helicobacter pylori in the pathogenesis of gastric cancer and gastric lymphoma. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:228–238. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randi G, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1591–1602. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boleij A, van Gelder MM, Swinkels DW, Tjalsma H. Clinical Importance of Streptococcus gallolyticus infection among colorectal cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:870–878. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Littman AJ, Jackson LA, Vaughan TL. Chlamydia pneumoniae and lung cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:773–778. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmid MC, Scheidegger F, Dehio M, Balmelle-Devaux N, Schulein R, Guye P, et al. A translocated bacterial protein protects vascular endothelial cells from apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinohara DB, Vaghasia AM, Yu SH, Mak TN, Bruggemann H, Nelson WG, et al. A mouse model of chronic prostatic inflammation using a human prostate cancer-derived isolate of Propionibacterium acnes. Prostate. 2013;73:1007–1015. doi: 10.1002/pros.22648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prorok-Hamon M, Friswell MK, Alswied A, Roberts CL, Song F, Flanagan PK, et al. Colonic mucosa-associated diffusely adherent afaC+ Escherichia coli expressing lpfA and pks are increased in inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. Gut. 2014;63:761–770. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of upper gastrointestinal malignancies. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:450–464. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao S, Brown J, Wang H, Feng X. The role of glycogen synthase kinase 3-beta in immunity and cell cycle: implications in esophageal cancer. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2014;62:131–144. doi: 10.1007/s00005-013-0263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hongo M, Nagasaki Y, Shoji T. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer: Orient to Occident. Effects of chronology, geography and ethnicity. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:729–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim R, Weissfeld JL, Reynolds JC, Kuller LH. Etiology of Barrett’s metaplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:369–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Tang L, Sun G, Tang Y, Xie Y, Wang S, et al. Etiological study of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in an endemic region: a population-based case control study in Huaian, China. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:287. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pei Z, Bini EJ, Yang L, Zhou M, Francois F, Blaser MJ. Bacterial biota in the human distal esophagus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4250–4255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306398101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pei Z, Yang L, Peek RM, Jr Levine SM, Pride DT, Blaser MJ. Bacterial biota in reflux esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7277–7283. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i46.7277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang L, Lu X, Nossa CW, Francois F, Peek RM, Pei Z. Inflammation and intestinal metaplasia of the distal esophagus are associated with alterations in the microbiome. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:588–597. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L, Francois F, Pei Z. Molecular pathways: pathogenesis and clinical implications of microbiome alteration in esophagitis and Barrett esophagus. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2138–2144. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Breaking bad: manipulation of the host response by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:328–338. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrian E, Mostefaoui Y, Rouabhia M, Grenier D. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases by Porphyromonas gingivalis in an engineered human oral mucosa model. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:56–62. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitmore SE, Lamont RJ. Oral bacteria and cancer. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003933. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn J, Segers S, Hayes RB. Periodontal disease, Porphyromonas gingivalis serum antibody levels and orodigestive cancer mortality. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1055–1058. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salazar CR, Sun J, Li Y, Francois F, Corby P, Perez-Perez G, et al. Association between selected oral pathogens and gastric precancerous lesions. PLoS One. 2013;8:e51604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salazar CR, Francois F, Li Y, Corby P, Hays R, Leung C, et al. Association between oral health and gastric precancerous lesions. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:399–403. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michaud DS. Role of bacterial infections in pancreatic cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2193–2197. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inaba H, Sugita H, Kuboniwa M, Iwai S, Hamada M, Noda T, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma through induction of proMMP9 and its activation. Cell Microbiol. 2014;16:131–145. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inaba H, Kuboniwa M, Sugita H, Lamont RJ, Amano A. Identification of signaling pathways mediating cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis in human trophoblasts. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2847–2857. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00258-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li N, Grivennikov SI, Karin M. The unholy trinity: inflammation, cytokines, and STAT3 shape the cancer microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:429–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H, Zhou H, Duan X, Jotwani R, Vuddaraju H, Liang S, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced reactive oxygen species activate JAK2 and regulate production of inflammatory cytokines through c-Jun. Infect Immun. 2014;82:4118–4126. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02000-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yee M, Kim S, Sethi P, Duzgunes N, Konopka K. Porphyromonas gingivalis stimulates IL-6 and IL-8 secretion in GMSM-K, HSC-3 and H413 oral epithelial cells. Anaerobe. 2014;28:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H, Kumar A, Lamont RJ, Scott DA. GSK3beta and the control of infectious bacterial diseases. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morandini AC, Ramos-Junior ES, Potempa J, Nguyen KA, Oliveira AC, Bellio M, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis Fimbriae Dampen P2X7-Dependent Interleukin-1beta Secretion. J Innate Immun. 2014;6:831–845. doi: 10.1159/000363338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yilmaz O, Yao L, Maeda K, Rose TM, Lewis EL, Duman M, et al. ATP scavenging by the intracellular pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis inhibits P2X7-mediated host-cell apoptosis. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:863–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yilmaz O, Jungas T, Verbeke P, Ojcius DM. Activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway contributes to survival of primary epithelial cells infected with the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3743–3751. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.3743-3751.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mao S, Park Y, Hasegawa Y, Tribble GD, James CE, Handfield M, et al. Intrinsic apoptotic pathways of gingival epithelial cells modulated by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1997–2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00931.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao L, Jermanus C, Barbetta B, Choi C, Verbeke P, Ojcius DM, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection sequesters pro-apoptotic Bad through Akt in primary gingival epithelial cells. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2010;25:89–101. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2010.00569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moffatt CE, Lamont RJ. Porphyromonas gingivalis induction of microRNA-203 expression controls suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 in gingival epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2632–2637. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00082-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuboniwa M, Hasegawa Y, Mao S, Shizukuishi S, Amano A, Lamont RJ, et al. P. gingivalis accelerates gingival epithelial cell progression through the cell cycle. Microbes Infect. 2008;10:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Homann N, Jousimies-Somer H, Jokelainen K, Heine R, Salaspuro M. High acetaldehyde levels in saliva after ethanol consumption: methodological aspects and pathogenetic implications. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1739–1743. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.9.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salaspuro MP. Acetaldehyde, microbes, and cancer of the digestive tract. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2003;40:183–208. doi: 10.1080/713609333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrissey D, O’Sullivan GC, Tangney M. Tumour targeting with systemically administered bacteria. Curr Gene Ther. 2010;10:3–14. doi: 10.2174/156652310790945575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dang LH, Bettegowda C, Huso DL, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Combination bacteriolytic therapy for the treatment of experimental tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15155–15160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251543698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yazawa K, Fujimori M, Amano J, Kano Y, Taniguchi S. Bifidobacterium longum as a delivery system for cancer gene therapy: selective localization and growth in hypoxic tumors. Cancer Gene Ther. 2000;7:269–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yazawa K, Fujimori M, Nakamura T, Sasaki T, Amano J, Kano Y, et al. Bifidobacterium longum as a delivery system for gene therapy of chemically induced rat mammary tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;66:165–170. doi: 10.1023/A:1010644217648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maekawa T, Krauss JL, Abe T, Jotwani R, Triantafilou M, Triantafilou K, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis manipulates complement and TLR signaling to uncouple bacterial clearance from inflammation and promote dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:768–778. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yilmaz O, Young PA, Lamont RJ, Kenny GE. Gingival epithelial cell signalling and cytoskeletal responses to Porphyromonas gingivalis invasion. Microbiology. 2003;149:2417–2426. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sztukowska M, Sroka A, Bugno M, Banbula A, Takahashi Y, Pike RN, et al. The C-terminal domains of the gingipain K polyprotein are necessary for assembly of the active enzyme and expression of associated activities. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:1393–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang MZ, Li CL, Jiang YT, Jiang W, Sun Y, Shu R, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection accelerates intimal thickening in iliac arteries in a balloon-injured rabbit model. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1192–1199. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]