Abstract

Background

The aim of the present study was to investigate the incidence of adverse events (AEs) during intra-hospital transport (IHT) of critically ill patients and evaluate the risk factors associated with these events.

Methods

This prospective multicenter observational study was performed in 34 intensive care units in China during 20 consecutive days from 5 November to 25 November 2012. All consecutive patients who required IHT for diagnostic testing or therapeutic procedures during the study period were included. All AEs that occurred during IHT were recorded. The incidence of AEs was defined as the rate of transports with at least one AE. The statistical analysis included a description of demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort as well as identification of risk factors for AEs during IHT by univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Results

In total, 441 IHTs of 369 critically ill patients were analyzed. The overall incidence of AEs was 79.8 % (352 IHTs). The proportion of equipment- and staff-related adverse events was 7.9 % (35 IHTs). The rate of patient-related adverse events (P-AEs) was 79.4 % (349 IHTs). The rates of vital sign–related P-AEs and arterial blood gas analysis–related P-AEs were 57.1 % (252 IHTs) and 46.9 % (207 IHTs), respectively. The incidence of critical P-AEs was 33.1 % (146 IHTs). The rates of vital sign–related critical P-AEs and arterial blood gas analysis–related critical P-AEs were 22.9 % (101 IHTs) and 15.0 % (66 IHTs), respectively. All data collected in our study were considered potential risk factors. In the multivariate analysis, predictive factors for P-AEs were pH, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood, lactate level, glucose level, and heart rate before IHT. Furthermore, the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood, lactate level, glucose level, heart rate, respiratory rate, pulse oximetry, and sedation before transport were independent influential factors for critical P-AEs during IHT.

Conclusions

The incidence of P-AEs during IHT of critically ill patients was high. Risk factors for P-AEs during IHT were identified. Strategies are needed to reduce their frequency.

Trial registration

Chinese Clinical Trial Register identifier ChiCTR-OCS-12002661. Registered 5 November 2012.

Background

Intra-hospital transport (IHT) is an inevitable and important part of intensive care unit (ICU) care. IHT is frequently required to perform diagnostic or therapeutic procedures for critically ill patients. Transported patients have more significant illnesses than patients not requiring transport [1]. Additionally, adverse events (AEs) during IHT occur commonly, and transported patients have significantly higher risks than non-transported patients in the ICU [1–3]. The decision to transport a critically ill patient is based on an assessment of the potential benefits and risks [4]. Knowledge of the incidence of AEs and risk factors for AEs during IHT is essential for scheduling safe ICU patient transport.

The overall incidence of AEs during IHT of critically ill patients reportedly ranges from 1.7 % to 75.7 % [5, 6]. Several explanations have been proposed for this wide range. One explanation is the different types of patients studied. Patients studied include those in the medical ICU [3], surgical ICU [7], anesthesiological ICU [6], neurological ICU [8], and emergency department [9–11]; mechanically ventilated patients [2, 3, 12]; and patients going to different transport destinations. Another explanation is the different definitions of AEs used among various reports. The most commonly used AE classifications are equipment/staff- and patient-related adverse events (P-AE) [12–14]. However, there is no standard definition of respiratory or circulatory AEs. A third explanation for the wide range of AEs during IHT is the different time periods studied. AEs related to IHT can occur during transport or secondarily even on the following day. Finally, the wide range may be explained by different programs used to limit AEs. This includes the use of specialized transport teams during IHT [5] or the use of designed transport checklists by acting nurses before the patients are transported [10].

To our knowledge, this is the first multicenter observational study to comprehensively identify the incidence and risk factors of AEs during the IHT of different ICU patients. These findings will help train a cadre of IHT personnel to perform safer ICU patient transport.

Methods

Study design and patients

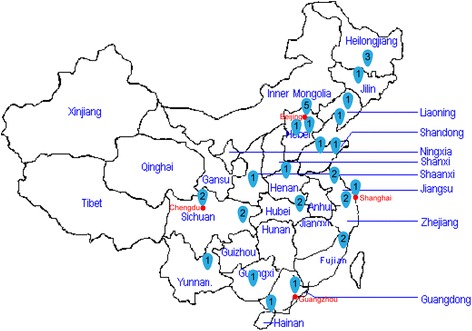

A prospective multicenter observational study was carried out in 34 closed ICUs (with staff members formally trained in critical care) in China during 20 consecutive days from 5 November to 25 November 2012 (Fig. 1). All consecutive patients who required IHT for diagnostic testing or therapeutic procedures during the study period were included. The study design and informed consent form were both approved by the medical ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (the organizer institution). The study was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Register as ChiCTR-OCS-12002661.

Fig. 1.

Thirty-four clinical centers in China participated in this study. Numbers represent number of centers at each location

No specific protocol, including special staff training, was used to manage critically ill patients before or during IHT. The risk or benefit of IHT for critically ill patients was assessed by the in-charge ICU physician. Patients who were transported to the operating room or the general ward after diagnostic testing were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their guardians or family members.

Data collection and outcome measures

Each participating ICU had a written procedure for data collection. All data were collected by trained observers from each participating ICU using a case report form. The observation period was divided into three parts: pre-IHT, IHT, and post-IHT. The pre-IHT period was defined as the time before the patient departed for IHT, and the post-IHT period was defined as the time after the patient returned to their ICU bed. Each period was measured with a maximum error of 5 minutes. All data in the pre-IHT period was established as baseline information.

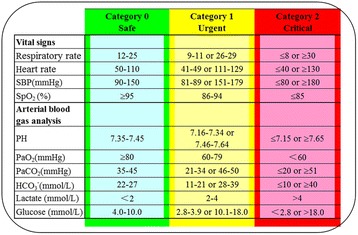

Patient characteristics were collected immediately after the patient was enrolled in the study. The severity of illness was determined using Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores obtained on the day of transport. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was evaluated on the basis of the patient’s last condition before transport if the patient had been sedated. IHT characteristics such as the transport destination were also recorded. Arterial blood gas analysis findings [pH, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2), partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood (PaCO2), bicarbonate, lactate level, and glucose level] were reviewed during the pre-IHT and post-IHT periods. Transport monitors were used to collect vital signs [systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), and pulse oximetry (SpO2)] every 5 minutes during the entire observation period. The vital signs and arterial blood gas analysis findings were categorized according to severity [15–17] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Severity categories of vital signs and arterial blood gas analysis. SBP systolic blood pressure, SpO 2 pulse oximetry, PaO 2 partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood, PaCO 2 partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood, HCO 3 − bicarbonate level

All AEs that occurred during IHT were recorded, regardless of whether a treatment was performed. AEs were classified as equipment- and staff-related adverse events (E-AEs) or as P-AEs. A P-AE was defined as any event that affected patient stability. A vital sign–related or arterial blood gas analysis–related P-AE was defined as an AE associated with detection of abnormal or more severe monitored parameters during the IHT period and the post-IHT period. A critical P-AE was defined as a vital sign or arterial blood gas analysis parameter with more severe abnormality detected (category 2 or worse), as well as other life-threatening events such as airway obstruction, accidental extubation, cardiac arrest, malignant arrhythmias, and others. Different AEs might occur during one transport. The incidence of AEs was defined as the rate of transports with at least one AE.

Data analysis

The sample size was calculated using the formula n = z 2 α/2π(1 − π)/δ2 (where α = 0.05, z α/2 = 1.96, π = 50 %, and δ = 5 %). Because the known incidence of AEs from previous studies of ICU patients during transport varies from 1.7 % to 75.7 %, we calculated the sample size as 384 IHTs with the assumption that 50 % of patients would experience an AE. We anticipated that 10 % of the data would be missing, which increased the target IHT sample size to 422.

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software (release 9.13, serial 989155; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Quantitative variables are reported as mean with standard deviation or as median with 25th and 75th percentiles. Qualitative data are described as values or percentages. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Possible risk factors for P-AEs during IHT were identified first by univariate logistic regression analysis. Those with a significance level <0.05 were included in a stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis. Results are reported as the odds ratio (OR) with 95 % confidence interval (CI).

Results

Patients and IHTs

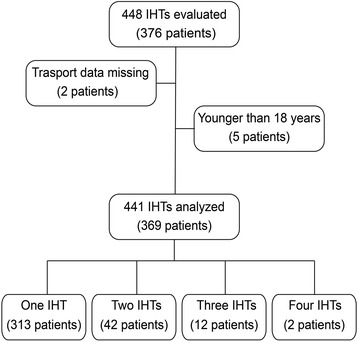

In total, 376 critically ill patients were enrolled during the study period (Fig. 3). These patients underwent 448 IHTs. Seven IHTs were excluded because of a lack of data documentation (n = 2) or a patient age <18 years (n = 5). Thus, 369 critically ill patients with 441 IHTs were included in the analysis. Fifty-six patients underwent more than 1 IHT, including 42 with 2 IHTs, 12 with 3 IHTs, and 2 with 4 IHTs. Thus, 72 IHTs were not the first IHT for that patient during that ICU stay. Patient and clinical characteristics before IHT were determined (Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 3.

Patients undergoing intra-hospital (IHT) transport

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 441 intra-hospital transports evaluated)

| Patient characteristic | Median | [25th–75th percentile] | Mean ± SD | Transports (n) | Transports (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 60 | [46–72] | 58.8 ± 18.0 | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 288 | 65.3 | |||

| Female | 153 | 34.7 | |||

| Weight, kg | 65 | [58–70] | 65.6 ± 12.5 | ||

| ICU admission type | |||||

| Medical | 163 | 37.0 | |||

| Surgical | 195 | 44.2 | |||

| Trauma | 46 | 10.4 | |||

| Other | 37 | 8.4 | |||

| APACHE II score | 14 | [9–21] | 15.4 ± 8.1 | ||

| GCS score | 15 | [9–15] | 11.9 ± 4.2 | ||

APACHE Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, GCS Glasgow Coma Scale, ICU intensive care unit SD standard deviation

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics before IHT (N = 441 intra-hospital transports evaluated)

| Clinical characteristic | Transports (n) | Transports (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial airway | 255 | 57.8 |

| Intubation | 144 | 32.7 |

| Tracheostomy | 111 | 25.2 |

| Mechanical ventilation | ||

| No ventilatory support | 237 | 53.7 |

| Nasal catheter | 155 | 35.1 |

| Face mask | 82 | 18.6 |

| Ventilatory support | 204 | 46.3 |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 8 | 1.8 |

| Invasive ventilation | 196 | 44.4 |

| Catheter use | ||

| Central venous | 317 | 71.9 |

| Peripheral vein | 171 | 38.8 |

| Arterial | 107 | 24.3 |

| Nasogastric tube | 291 | 66.0 |

| Foley catheter | 311 | 70.5 |

| Drainage catheter | 138 | 31.3 |

| Other | 22 | 5.0 |

| Vasoactive drug supporta | 107 | 24.3 |

| Catecholamines | 62 | 14.1 |

| Vasodilator | 28 | 6.4 |

| Other | 10 | 2.3 |

| More than one of above | 7 | 1.6 |

| Sedationa | 102 | 23.1 |

| Midazolam | 36 | 8.2 |

| Propofol | 35 | 7.9 |

| Dexmedetomidine | 18 | 4.1 |

| Other | 3 | 0.7 |

| More than one of the above | 10 | 2.3 |

| Analgesiaa | 67 | 15.2 |

| Opioid | 60 | 13.6 |

| Non-opioid | 7 | 1.6 |

| Severity categories of vital signsb | ||

| Respiratory rate | ||

| Category 0 | 346 | 78.5 |

| Category 1 | 48 | 10.9 |

| Category 2 | 47 | 10.7 |

| Heart rate | ||

| Category 0 | 355 | 80.5 |

| Category 1 | 65 | 14.7 |

| Category 2 | 21 | 4.8 |

| Systolic blood pressure | ||

| Category 0 | 381 | 86.4 |

| Category 1 | 51 | 11.6 |

| Category 2 | 9 | 2.0 |

| SpO2 | ||

| Category 0 | 391 | 88.7 |

| Category 1 | 47 | 10.7 |

| Category 2 | 3 | 0.7 |

| Severity categories of ABGb | ||

| pH | ||

| Category 0 | 253 | 57.4 |

| Category 1 | 186 | 42.2 |

| Category 2 | 2 | 0.5 |

| PaO2 | ||

| Category 0 | 326 | 73.9 |

| Category 1 | 95 | 21.5 |

| Category 2 | 20 | 4.5 |

| PaCO2 | ||

| Category 0 | 197 | 44.7 |

| Category 1 | 218 | 49.4 |

| Category 2 | 26 | 5.9 |

| Bicarbonate level | ||

| Category 0 | 220 | 49.9 |

| Category 1 | 217 | 49.2 |

| Category 2 | 4 | 0.9 |

| Lactate level | ||

| Category 0 | 345 | 78.2 |

| Category 1 | 72 | 16.3 |

| Category 2 | 24 | 5.4 |

| Glucose level | ||

| Category 0 | 333 | 75.5 |

| Category 1 | 101 | 22.9 |

| Category 2 | 7 | 1.6 |

SBP systolic blood pressure, SpO 2 pulse oximetry, ABG arterial blood gas, PaO 2 partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood, PaCO 2 partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood

aMedications were delivered as continuous infusions

bSeverity categories defined in Fig. 2

Patient IHT characteristics were evaluated (Table 3). In total, 433 IHTs (98.2 %) were to only one location, most commonly for computed tomographic imaging (380 IHTs, 86.2 %). Other destinations included ultrasonography (18 IHTs, 4.1 %), radiation treatment (8 IHTs, 1.8 %), magnetic resonance imaging (7 IHTs, 1.6 %), endoscopy (4 IHTs, 0.9 %), and angiography (4 IHTs, 0.9 %). Only eight IHTs (1.8 %) were to more than one location. Eighty-three IHTs (18.8 %) were emergent. The majority of IHTs (438 IHTs, 99.3 %) were carried out successfully. Three patients were not transferred successfully, owing to serious AEs (airway obstruction, accidental extubation, and a low SpO2 of 60 %, respectively). A minority of IHTs were performed between 5:00 pm and 8 am (27 IHTs, 6.1 %). The median duration of IHT was 25 minutes (25th–75th percentile range 20–35 minutes).

Table 3.

Intra-hospital transport characteristics (N = 441 intra-hospital transports evaluated)

| IHT characteristic | Transports (n) | Transports (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Transport destination | ||

| Computed tomography | 380 | 86.2 |

| Ultrasonography | 18 | 4.1 |

| Radiation therapy | 8 | 1.8 |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 7 | 1.6 |

| Digestive endoscopy | 4 | 0.9 |

| Angiography | 4 | 0.9 |

| Other | 12 | 2.7 |

| Multiple destinations | 8 | 1.8 |

| Transport type | ||

| Emergency | 83 | 18.8 |

| Elective | 358 | 81.2 |

| Multiple IHTs of one patient | 72 | 16.3 |

| Transport time | ||

| Daytime (8:00 am–5:00 pm) | 414 | 93.9 |

| Nighttime (5:00 pm–8:00 am) | 27 | 6.1 |

| Medications administered during IHTa | ||

| Analgesia | 45 | 10.2 |

| Sedation | 80 | 18.1 |

| Vasoactive drug support | 92 | 20.7 |

| Completed transports | 438 | 99.3 |

IHT intra-hospital transport

aMedications were delivered as continuous infusion

AEs during IHT

Table 4 shows the incidence and types of AEs during IHT. The overall incidence of AEs was 79.8 % (352 IHTs). The proportion of E-AEs was 7.9 % (35 IHTs). Most of these involved a disconnected monitor power source or monitor power failure (11 IHTs, 2.5 %), disconnected or depleted oxygen supply (9 IHTs, 2.0 %), or unexpected delays during transport (8 IHTs, 1.8 %). The rate of P-AEs was 79.4 % (349 IHTs). The rates of vital sign–related P-AEs and arterial blood gas analysis–related P-AEs were 57.1 % (252 IHTs) and 46.9 % (207 IHTs), respectively. Other P-AEs comprised mainly anxiety (66 IHTs, 15.0 %), agitation (49 IHTs, 11.1 %), resistance to ventilation when intubated (54 IHTs, 12.2 %), and pain or discomfort (27 IHTs, 6.1 %). The incidence of critical P-AEs was 33.1 % (146 IHTs) (Table 5). The rates of vital sign–related and arterial blood gas analysis–related critical P-AEs were 22.9 % (101 IHTs) and 15.0 % (66 IHTs), respectively. The majority of these AEs involved RR abnormality or more severe (54 IHTs, 12.2 %), HR abnormality or more severe (31 IHTs, 7.0 %), PaO2 abnormality or more severe (30 IHTs, 6.8 %), and lactate level abnormality or more severe (28 IHTs, 6.4 %). One accidental extubation and one airway obstruction occurred. No patient experienced cardiac arrest during the study period.

Table 4.

Adverse events during intra-hospital transports (N = 441 intra-hospital transports evaluated)

| Adverse event | Transportsa (n) | Transports (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total AEs | 352 | 79.8 |

| Equipment- or staff-related AEs | 35 | 7.9 |

| Loss of monitor power | 11 | 2.5 |

| Vascular tubing obstructed | 4 | 0.9 |

| Disconnected or depleted of oxygen supply | 9 | 2.0 |

| Loss of ventilator power | 3 | 0.7 |

| Unexpected delay ≥15 minutes | 8 | 1.8 |

| Other | 4 | 0.9 |

| Patient-related AEs (P-AEs) | 349 | 79.4 |

| Vital sign–related P-AEsb | 252 | 57.1 |

| RR abnormality or more severe | 99 | 22.5 |

| HR abnormality or more severe | 69 | 15.7 |

| SBP abnormality or more severe | 78 | 17.7 |

| SpO2 abnormality or more severe | 102 | 23.1 |

| Arterial blood gas analysis–related P-AEsb | 207 | 46.9 |

| pH abnormality or more severe | 53 | 12.0 |

| PaO2 abnormality or more severe | 70 | 15.9 |

| PaCO2 abnormality or more severe | 63 | 14.3 |

| HCO3 − abnormality or more severe | 36 | 8.2 |

| Lactate level abnormality or more severe | 42 | 9.5 |

| Glucose level abnormality or more severe | 39 | 8.8 |

| New-onset arrhythmia | 3 | 0.7 |

| Anxiety | 66 | 15.0 |

| Agitation | 49 | 11.1 |

| Pain or discomfort | 27 | 6.1 |

| Resistance to ventilation when intubated | 54 | 12.2 |

| Accidental extubation | 1 | 0.2 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 2 | 0.5 |

| Airway obstruction | 1 | 0.2 |

| Other | 2 | 0.5 |

AE adverse event, RR respiratory rate, HR heart rate, SBP systolic blood pressure, SpO 2 pulse oximetry, PaO 2 partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood, PaCO 2 partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood, HCO 3 − bicarbonate level

aNumber of transports with at least one AE

bDefined as an AE associated with detection of abnormal or more severe monitored parameters during the intra-hospital transport (IHT) period and post-IHT period

Table 5.

Critical patient-related adverse events during intra-hospital transports (N = 441 intra-hospital transports evaluated)

| Critical patient-related adverse events | Transportsa (n) | Transports (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total critical P-AEs | 146 | 33.1 |

| Vital sign–related critical P-AEsb | 101 | 22.9 |

| RR abnormality or more severe | 54 | 12.2 |

| HR abnormality or more severe | 31 | 7.0 |

| SBP abnormality or more severe | 21 | 4.7 |

| SpO2 abnormality or more severe | 11 | 2.5 |

| Arterial blood gas analysis–related critical P-AEsb | 66 | 15.0 |

| pH abnormality or more severe | 2 | 0.5 |

| PaO2 abnormality or more severe | 30 | 6.8 |

| PaCO2 abnormality or more severe | 7 | 1.6 |

| HCO3 − abnormality or more severe | 3 | 0.7 |

| Lactate level abnormality or more severe | 28 | 6.4 |

| Glucose level abnormality or more severe | 6 | 1.4 |

| Accidental extubation | 1 | 0.2 |

| Airway obstruction | 1 | 0.2 |

P-AE patient-related adverse events, RR respiratory rate, HR heart rate, SBP systolic blood pressure, SpO 2 pulse oximetry, PaO 2 partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood, PaCO 2 partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood, HCO 3 − bicarbonate level

aNumber of transports with at least one AE

bDefined as a parameter with more severe abnormality detected (category 2 or worse in Fig. 2)

When a vital sign–related P-AE was defined as an AE associated with detection of abnormal or more severe monitored parameters only in the post-IHT period, the rates of vital sign–related P-AEs and critical P-AEs were 29.5 % (130 IHTs) and 11.8 % (52 IHTs), respectively.

Risk factors for P-AEs during IHT

Univariate and stepwise multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors present before or during IHT that were related to an increase in P-AEs in critically ill patients during transport. Comparisons were made between reference category and each of the remaining groups per characteristic.

Table 6 shows the risk factors for P-AEs during IHT. Patient characteristics did not significantly affect the occurrence of P-AEs during transport. Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that the APACHE II score and vasoactive drug support before transport were associated with P-AEs during IHT. More specifically, patients with an APACHE II score ≥20 had a significantly higher incidence of P-AEs than did those with an APACHE II score ≤11 (P = 0.02). More P-AEs occurred in patients with a pH, PaCO2, lactate level, glucose level, HR, and RR in severity category 1 or 2 than in severity category 0 (P < 0.05). However, after adjusting for potential confounding factors through the multivariate analysis, only pH, PaCO2, lactate level, glucose level, and HR were independent influential factors for P-AEs during IHT (P < 0.05). Significantly more P-AEs occurred in patients with these parameters in severity category 1 or 2 than in severity category 0 (P < 0.05). Ventilation and transport characteristics were not associated with P-AEs during IHT. There was no evidence that patients receiving analgesia or sedation had more P-AEs during transport.

Table 6.

Risk factors for patient-related adverse events during intra-hospital transport

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95 % CI) | P value | OR (95 % CI) | P value | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age, yr | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.67 | NT | |

| Sex | 0.94 (0.58–1.51) | 0.79 | NT | |

| Weight, kg | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.06 | NT | |

| < 65 | Reference | – | ||

| ≥ 65 | 1.46 (0.92–2.32) | 0.11 | ||

| ICU admission type | 1.04 (0.80–1.34) | 0.79 | NT | |

| Clinical characteristics before transport | ||||

| APACHE II score | 1.43 (1.06–1.91) | 0.02* | ||

| ≤ 11 | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| 12–19 | 1.25 (0.74–2.12) | 0.40 | 1.27 (0.73–2.22) | 0.40 |

| ≥ 20 | 2.11 (1.14–3.88) | 0.02* | 1.89 (0.98–3.67) | 0.06 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score | 1.14 (0.86–1.51) | 0.36 | NT | |

| 15 | Reference | – | ||

| 9–14 | 0.86 (0.47–1.56) | 0.62 | ||

| ≤ 8 | 1.39 (0.77–2.51) | 0.27 | ||

| Artificial airway | 1.26 (0.80–2.01) | 0.32 | NT | |

| Ventilation | 1.22 (0.77–1.94) | 0.40 | NT | |

| Number of catheters | 1.24 (1.00–1.54) | 0.05 | NT | |

| Arterial blood gas analysis | ||||

| pH | ||||

| 7.35–7.45 | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| < 7.35 or >7.45 | 1.55 (1.34–1.88) | 0.01* | 1.53 (1.32–1.88) | 0.01* |

| PaO2 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.07 | NT | |

| PaCO2, mmHg | ||||

| 35–45 | Reference | – | ||

| < 35 or >45 | 1.61 (1.38–1.97) | 0.04* | 1.49 (1.29–1.81) | 0.00* |

| Bicarbonate level, mmol/L | NT | |||

| 22–27 | Reference | – | ||

| < 22 or >27 | 1.08 (0.68–1.71) | 0.75 | ||

| Lactate level, mmol/L | 1.60 (1.17–2.18) | 0.00* | ||

| < 2 | reference | – | Reference | – |

| ≥ 2 | 2.11 (1.10–4.07) | 0.03* | 1.47 (1.04–2.08) | 0.03* |

| Glucose level, mmol/L | ||||

| 4.0–10.0 | Reference | – | ||

| < 4 or >10 | 2.27 (1.21–4.28) | 0.01* | 1.97 (1.01–3.84) | 0.04* |

| Vital signs | ||||

| SBP, mmHg | NT | |||

| 90–150 | Reference | – | ||

| < 90 or >150 | 1.37 (0.67–2.82) | 0.39 | ||

| DBP, mmHg | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.12 | NT | |

| MAP, mmHg | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.08 | NT | |

| Heart rate | ||||

| 50–110 | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| < 50 or >110 | 3.02 (1.40–6.51) | 0.00* | 2.73 (1.21–6.16) | 0.02* |

| Respiratory rate | ||||

| 12–25 | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| < 12 or >25 | 2.33 (1.19–4.59) | 0.01* | 2.00 (0.98–4.10) | 0.06 |

| Pulse oximetry | 0.93 (0.85–1.02) | 0.13 | NT | |

| Analgesia | 1.60 (0.78–3.27) | 0.20 | NT | |

| Sedation | 1.42 (0.80–2.54) | 0.24 | NT | |

| Vasoactive drug support | 2.02 (1.09–3.75) | 0.03* | 1.85 (0.97–3.55) | 0.06 |

| Transport characteristics | ||||

| Analgesia | 1.25 (0.56–2.78) | 0.59 | NT | |

| Sedation | 1.07 (0.58–1.95) | 0.83 | NT | |

| Vasoactive drug support | 1.60 (0.86–2.99) | 0.14 | NT | |

| Emergency transport | 0.52 (0.26–1.03) | 0.06 | NT | |

| Multiple IHTs of one patient | 1.29 (0.76–2.18) | 0.34 | NT | |

| Night transport | 0.64 (0.22–1.91) | 0.43 | NT | |

| Transport duration, minutes | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.32 | NT | |

APACHE Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, PaO 2 partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood, PaCO 2 partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, MAP mean arterial pressure, NT not tested, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

*P < 0.05

Risk factors for critical P-AEs during IHT are shown in Table 7. Univariate logistic regression analysis identified pre-IHT parameters or transport characteristics associated with P-AEs during IHT (P < 0.05), namely weight, APACHE II score, GCS score, number of catheters, PaO2, lactate level, glucose level, HR, RR, SpO2, sedation before transport, vasoactive drug support during transport, and emergency transport. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, APACHE II score, PaO2, lactate level, glucose level, HR, RR, SpO2, and sedation before transport were independent influential factors for critical P-AEs during IHT (P < 0.05). Furthermore, patients with an APACHE II score ≥20 had a significantly higher incidence of critical P-AEs than did patients with an APACHE II score ≤11 (P = 0.01). A significantly higher rate of critical P-AEs occurred in patients with a parameter pre-IHT (PaO2, lactate level, glucose level, HR, RR, and SpO2) in severity category 1 or 2 than in severity category 0 (P < 0.05). Ventilation, night transport, multiple IHTs of one patient, and transport duration were not associated with critical P-AEs during IHT.

Table 7.

Risk factors for critical patient-related adverse events during intra-hospital transport

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95 % CI) | P value | OR (95 % CI) | P value | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age, yr | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.71 | NT | |

| Sex | 0.70 (0.46–1.08) | 0.10 | NT | |

| Weight, kg | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | 0.00* | ||

| < 65 | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| ≥ 65 | 1.95 (1.30–2.94) | 0.00* | 1.55 (0.95–2.54) | 0.08 |

| ICU admission type | 0.95 (0.76–1.19) | 0.67 | NT | |

| Clinical characteristics before transport | ||||

| APACHE II score | 1.66 (1.29–2.14) | 0.00* | ||

| ≤ 11 | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| 12–19 | 1.66 (1.01–2.74) | 0.04* | 1.44 (0.79–2.63) | 0.23 |

| ≥ 20 | 2.75 (1.66–4.57) | 0.00* | 2.49 (1.23–5.03) | 0.01* |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score | 0.76 (0.60–0.96) | 0.02* | ||

| 15 | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| 9–14 | 0.93 (0.53–1.64) | 0.80 | 0.67 (0.33–1.38) | 0.28 |

| ≤ 8 | 1.82 (1.14–2.91) | 0.01* | 0.89 (0.46–1.74) | 0.74 |

| Artificial airway | 1.38 (0.92–2.07) | 0.12 | NT | |

| Ventilation | 1.48 (0.99–2.20) | 0.06 | NT | |

| Number of catheter | 1.28 (1.07–1.54) | 0.01* | 1.20 (0.95–1.51) | 0.13 |

| Arterial blood gas analysis | ||||

| pH | NT | |||

| 7.35–7.45 | Reference | – | ||

| < 7.35 or >7.45 | 1.03 (0.69–1.54) | 0.88 | ||

| PaO2, mmHg | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.00* | ||

| ≥ 80 | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| < 80 | 2.49 (1.61–3.86) | 0.00* | 2.26 (1.31–3.91) | 0.00* |

| PaCO2, mmHg | NT | |||

| 35–45 | Reference | – | ||

| < 35 or >45 | 1.36 (0.91–2.02) | 0.13 | ||

| Bicarbonate level, mmol/L | NT | |||

| 22–27 | Reference | – | ||

| < 22 or >27 | 1.28 (0.86–1.92) | 0.23 | ||

| Lactate level, mmol/L | 1.87 (1.51–2.33) | 0.00* | ||

| < 2 | Reference | – | ||

| ≥ 2 | 2.82 (1.77–4.49) | 0.00* | 3.12 (1.75–5.58) | 0.00* |

| Glucose level, mmol/L | ||||

| 4.0–10.0 | Reference | – | ||

| < 4 or >10 | 2.24 (1.43–3.50) | 0.00* | 1.80 (1.05–3.08) | 0.03* |

| Vital signs | ||||

| SBP, mmHg | NT | |||

| 90–150 | Reference | – | ||

| < 90 or >150 | 1.10 (0.62–1.95) | 0.74 | ||

| DBP, mmHg | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.64 | NT | |

| MAP, mmHg | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.95 | NT | |

| Heart rate | ||||

| 50–110 | Reference | – | ||

| < 50 or >110 | 4.53 (2.76–7.42) | 0.00* | 2.97 (1.66–5.32) | 0.00* |

| Respiratory rate | ||||

| 12–25 | Reference | – | ||

| < 12 or >25 | 3.06 (1.92–4.89) | 0.00* | 2.45 (1.39–4.33) | 0.00* |

| Pulse oximetry | 0.84 (0.78–0.91) | 0.00* | ||

| ≥ 95 | Reference | – | ||

| < 95 | 3.56 (1.94–6.52) | 0.00* | 2.79 (1.31–5.95) | 0.01* |

| Analgesia | 1.34 (0.78–2.30) | 0.28 | NT | |

| Sedation | 1.96 (1.25–3.09) | 0.00* | 1.87 (1.07–3.29) | 0.03* |

| Vasoactive drug support | 1.51 (0.96–2.37) | 0.07 | NT | |

| Transport characteristics | ||||

| Analgesia | 0.90 (0.47–1.76) | 0.76 | NT | |

| Sedation | 1.27 (0.77–2.10) | 0.36 | NT | |

| Vasoactive drug support | 1.76 (1.10–2.83) | 0.02* | 1.63 (0.92–2.88) | 0.10 |

| Emergency transport | 1.54 (1.33–1.89) | 0.01* | 1.26 (0.68–2.35) | 0.47 |

| Multiple IHTs of one patient | 0.84 (0.54–1.31) | 0.45 | NT | |

| Night transport | 0.83 (0.37–1.87) | 0.65 | NT | |

| Transport duration, minutes | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.18 | NT | |

APACHE Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, PaO 2 partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood, PaCO 2 partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood, SBP Systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, MAP mean arterial pressure, NT not tested, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

*P < 0.05

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective multicenter study of the incidence and risk factors for AEs during IHT in both medical and surgical ICU patients, including both mechanically ventilated and non-ventilated patients. Three previous reports of IHT of ICU patients contained more transports than our study. One observational study was carried out in a cohort of 452 IHTs of 226 adults and infants from 3 anesthesiology ICUs in Austria [6]. In total, 4.2 % of IHTs were associated with a critical incident. Kue et al. [5] reported an AE rate of 1.7 % in a retrospective study of 3358 IHTs by a specialized transport team in the United States. AEs included hypoxia and alterations in blood pressure. Furthermore, a multicenter cohort of 1782 mechanically ventilated adult ICU patients with 3006 IHTs experienced 621 AEs (37.4 %). The authors of that study compared 1659 transported patients with 3344 patients who were not transported [2]. Pneumothorax, atelectasis, ventilator-associated pneumonia, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and hypernatremia were reported as complications that occurred more frequently in the transported population. A longer ICU stay, but not a higher mortality rate, was found in transported patients than in non-transported patients. No risk factors for AEs were reported. Perhaps an approach integrating multiple vital signs derangements in one score, such as the Modified Early Warning Score, might be helpful as a predictor. Additionally, AEs have been reported in many studies with more critically ill patients during inter-hospital transport [18–23] than we included in our study, but few data have documented the risks [24–26]. Although these findings were derived from studies on inter-hospital transport, they may also apply to IHT [20].

Definition of AEs during IHT

Reported rates of transfer-related AEs vary among different studies, not only because of differences in incidences but also because different definitions were used [22]. How to more reasonably define vital sign–related or laboratory work–related AEs is unclear. First, conditions of critically ill patients are prone to change even without transport. It is difficult to tell if these changes would have occurred if the patients had remained where they were. Second, no definition perfectly distinguishes whether such changes are actually adverse or simply represent physiologic variability among patients. Third, sicker patients are more likely to deteriorate during transfer [23]. Therefore, even a minimal change in vital signs or laboratory work might be clinically important.

Vital signs and arterial blood gas analysis findings were classified according to their severity in our study, and changes in severity categories were used to define vital sign–related and arterial blood gas analysis–related P-AEs. However, not all of the above-mentioned problems can be solved by this definition. We believe that a consensus on the definition of transfer-related AEs must be reached in the future to allow for appropriate comparison of AE rates.

Incidence of AE

In this study, we evaluated 369 adult critically ill patients with 441 IHTs. The overall incidence of AEs was 79.8 %, and 33.1 % of IHTs were associated with a critical P-AE. These findings are similar to those in some previous reports [9, 12–14] but greater than those in the largest studies evaluating IHT of ICU patients. These results are noteworthy, such that physicians should pay greater attention to the safety of critically ill patients during IHT.

A greater number of clinical characteristics were assessed in our study than in previous reports. The high AE rate found in our study is attributable to the definition of P-AE. First, vital signs were monitored and noted every 5 minutes during transport; thus, more transient events might have been captured than in previous studies [2]. In total, 57.1 % of the IHTs were associated with vital sign–related P-AEs, and 22.9 % of the IHTs were associated with vital sign–related critical P-AEs. However, if changes in these variables during the IHT period were not detected (vital signs were observed or collected just before and after transport, like in most previous studies), the rates of vital sign–related P-AEs and critical P-AEs were 29.5 % and 11.8 %, respectively. More than half of the vital sign–related P-AEs might not have been identified. Second, the careful observation of arterial blood gas values before and after IHT may also have contributed to the high AE rate, assessed in few previous studies [12, 27]. The incidence of arterial blood gas analysis–related P-AEs was unexpectedly high (46.9 % of IHTs). Additionally, AEs during IHT related to lactate (42 IHTs, 9.5 %) and bicarbonate (36 IHTs, 8.2 %) levels have not been reported previously. Patient glucose levels during IHT were described in only one recent report [2]. The rates of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia in this study were 3.38 % and 23.75 %, respectively. The percentage of glucose level deterioration was 8.8 % (39 IHTs) in our study, and a low rate of critical glucose level deterioration was found in our patients (6 IHTs, 1.4 %). These occurrences may be secondary to interruptions in nutrition support or insulin therapy during transport.

Identification of E-AEs is important because such AEs can lead to P-AEs. The incidence of E-AEs in the present study (35 IHTs, 7.9 %) was lower than rates reported in previous studies (11–34 %) [13, 28]. Most E-AEs were related to a disconnected power source or power failure of a monitor, a disconnected or depleted oxygen supply, or unexpected delays. These AEs were associated with insufficient preparation before IHT that did not take into account potential risk factors. Careful preparation of equipment before transport and assistance by well-trained personnel during IHT should minimize these problems.

Risk factors for P-AEs

Accurate assessment of the risk/benefit ratio of each transport is the key to reducing AEs during IHT of critically ill patients. Physicians should consider both the indications for and risk factors associated with IHT.

Adult ICU assessment models of illness severity have been used to predict patient outcomes for three decades [29, 30]. Several researchers have evaluated the predictive value of AEs during transport of critically ill patients. The Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System score is reportedly associated with the occurrence of AEs during transport [31]. The Simplified Acute Physiology Score II and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score have not been reported to predict AEs during transport [3, 25]. Disease severity as assessed by APACHE II scores was correlated with a higher risk of physiologic deterioration [6]. In the present study, the APACHE II score on the day of IHT was not an independent influential factor for P-AEs during IHT, but patients with an APACHE II score ≥20 had a significantly higher incidence of critical P-AEs than did patients with an APACHE II score ≤11. Further work is needed to evaluate the use of illness severity scores in predicting AEs during IHT.

The use of artificial airways was not associated with P-AEs during IHT by logistic regression analysis. Ventilated patients experience physical discomfort, anxiety, and hemodynamic instability and might be at higher risk for P-AEs during transport. However, our study showed that mechanical ventilation was not a risk factor for P-AEs during IHT, in contrast to previous reports [6, 26]. This result may be because of the lower incidence of E-AEs in our study or because ventilation settings were not analyzed in this study. Better characterization of these risks in patients requiring ventilation is needed.

Excluding the bicarbonate level, arterial blood gas analysis parameters before transport were significantly related to P-AEs or critical P-AEs during IHT in our study. These variables have not been studied as potential risk factors for AEs during IHT of ICU patients. Strauch et al. [25] reported that patients who died within 24 h after inter-hospital transport had a lower pH. Patients with an abnormal pH and PaCO2 were more prone to developing P-AEs during transport, and PaO2 was an independent influential factor for critical P-AEs. Blood lactate concentrations have been widely used as an indicator of disease severity [32, 33], and elevated lactate clearance is reportedly predictive of lower mortality in critically ill patients [34]. A high lactate level (≥2 mmol/L) before transport was a predictive factor for P-AEs or critical P-AEs during IHT of the patients in the present study. Additionally, a glucose level <4 or >10 mmol/L before transport was identified as a predictive factor for P-AEs or critical P-AEs during IHT.

Patients with physiologic instability before transport had a higher incidence of AEs during inter-facility transport [18]. Abnormal vital signs are reported to be strongly associated with adverse outcomes [15]. Our study found that vital signs were associated with P-AEs during IHT; this has not been described in previous studies. Patients with an HR <50 or >110 had more P-AEs than those in a safe severity category. Furthermore, RR and SpO2 were both influential factors for critical P-AEs during IHT. However, blood pressure was not found to be related to the occurrence of P-AEs in our study.

The duration of transport is also reportedly associated with AEs during transport of critically ill patients [26, 31]. IHT should be coordinated with the destination to shorten travel time and delays as much as possible. However, our results showed that a long IHT duration was not a significant risk factor for P-AEs, which is the same result found by Seymour et al. [24]. Unlike a similar study [6], emergency transport was not found to significantly increase the risk of P-AEs in our patients. Night transport and multiple IHTs of the same patient at different times were not risk factors for P-AEs during IHT, as previously described [3, 6]. These transport-related factors must be further investigated with more IHT cases.

Anxiety or agitation was recorded in more than 25 % of transports. Pain, discomfort, and resistance to ventilation when intubated occurred in about 19 % of IHTs. These AEs were perhaps due to inadequate analgesia and sedation in our patients. Patient sedation before transport is a well-described risk factor for AEs during IHT [3], but sedation was associated only with critical P-AEs in our study. Further research on this association is needed.

Strategies to minimize AEs

Various maneuvers have been reported to improve patient IHT outcomes. Transport monitors are not routinely used during the IHT of ICU patients in China, although recommendations for their use have been published [35]. Transport monitoring is an essential part of IHT. Manual ventilation of critically ill mechanically ventilated patients can be performed safely during transport [36]. However, transport ventilators provide more reliable and stable ventilatory support than do manual ventilators and are preferable for IHT [27]. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation is increasingly being used in patients with acute respiratory failure in the ICU setting [37]. The authors of one study reported that dedicated non-invasive ventilators allow better patient–ventilator synchrony than do ICU and transport ventilators [38]. Availability of a medical emergency team can also improve outcomes after AEs [39]. Use of resistive heating has been shown to be effective in maintaining the core temperature of ICU patients during IHT [40].

Recommendations for the IHT of critically ill patients have been published [4, 35, 41–44]. These recommendations cover pretransport coordination and communication, care of patient equipment, patient monitoring during transport, preparation of the patient before transport, documentation of transport, and training of caregivers involved in the transport processes. However, hospitals should implement policies and procedures to mitigate the risks associated with IHT in practice [45].

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. The impact of IHT on patient outcomes, such as the ICU or hospital length of stay and mortality rate, was not evaluated. Risk factors for E-AEs during IHT were not analyzed, owing to the inadequate case numbers. Because more than 50 % of the data for pain scales and sedation scores before or during transport were missing, their predictive values for AEs were not assessed in our study. Patient diagnosis, electrolyte levels, use of neuromuscular blockade medication, use of nutritional support, fluid therapy, use of infusion pumps, ventilator modes and settings, and accompanying personnel were also not evaluated as potential influential factors for P-AEs. Finally, standardized methods to transport patients, such as the use of transport protocols or well-trained transport teams, may reduce the incidence of AEs during transport. These programs used in the ICUs that participated in our study might have been important influential factors for AEs. However, the information was not recorded, and further research is needed.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective multicenter study to comprehensively identify the incidence and risk factors of AEs during the IHT of different ICU patients. A high P-AE rate was found in our patients. Risk factors for P-AEs during IHT were identified. These included abnormal pH and PaCO2, high lactate levels, and specific glucose levels before transport. Critical P-AEs were associated with the APACHE II score, PaO2, lactate level, glucose level, HR, RR, SpO2, and sedation before transport. Strategies designed to minimize AEs during IHT are needed in practice.

Key messages

The incidence of P-AEs during IHT of ICU patients in this multicenter study in China was very high.

New risk factors for P-AEs during IHT were abnormal PH and PaCO2, high lactate levels, and specific glucose level before transport. Critical P-AE was associated with APACHE II score, PaO2, lactate level, glucose level, HR, RR, SpO2, and sedation before transport.

Strategies designed to minimize AE during IHT are needed in practice.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all participating ICUs for providing data. We also acknowledge Jiangsu Singch Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. for funding this study.

Abbreviations

- ABG

arterial blood gas

- AE

adverse event

- APACHE

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- CI

confidence interval

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- E-AE

equipment- and staff-related adverse event

- GCS

Glasgow Coma Scale

- HCO3−

bicarbonate level

- HR

heart rate

- ICU

intensive care unit

- IHT

intra-hospital transport

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MEWS

Modified Early Warning Score

- NT

not tested

- OR

odds ratio

- PaCO2

partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood

- P-AE

patient-related adverse event

- PaO2

partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood

- RR

respiratory rate

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- SpO2

pulse oximetry

Footnotes

Liu Jia and Hongliang Wang contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LJ and HW conceived the study, oversaw all aspects of the study, designed of the study, analyzed the data, and drafted and revised the manuscript. YG assisted in study design, performed data acquisition, and helped to draft the manuscript. HL helped with the acquisition and interpretation of data and revised the manuscript. KY participated in the design of the study, carried out data analysis, and helped to draft and revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Kaijiang Yu is the president of Chinese Society of Critical Care Medicine, and president of the third Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University.

Contributor Information

Liu Jia, Email: jialiu179@163.com.

Hongliang Wang, Email: icuwanghongliang@163.com.

Yang Gao, Email: gaoyang0312@126.com.

Haitao Liu, Email: dr633@foxmail.com.

Kaijiang Yu, Email: icuyukaijiang@163.com.

References

- 1.Voigt LP, Pastores SM, Raoof ND, Thaler HT, Halpern NA. Review of a large clinical series: intrahospital transport of critically ill patients: outcomes, timing, and patterns. J Intensive Care Med. 2009;24:108–15. doi: 10.1177/0885066608329946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwebel C, Clec’h C, Magne S, Minet C, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Bonadona A, et al. Safety of intrahospital transport in ventilated critically ill patients: a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1919–28. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a3bbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parmentier-Decrucq E, Poissy J, Favory R, Nseir S, Onimus T, Guerry MJ, et al. Adverse events during intrahospital transport of critically ill patients: incidence and risk factors. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3:10. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warren J, Fromm RE, Jr, Orr RA, Rotello LC, Horst HM. Guidelines for the inter- and intrahospital transport of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:256–62. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000104917.39204.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kue R, Brown P, Ness C, Scheulen J. Adverse clinical events during intrahospital transport by a specialized team: a preliminary report. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20:153–62. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lahner D, Nikolic A, Marhofer P, Koinig H, Germann P, Weinstabl C, et al. Incidence of complications in intrahospital transport of critically ill patients – experience in an Austrian university hospital. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119:412–6. doi: 10.1007/s00508-007-0813-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szem JW, Hydo LJ, Fischer E, Kapur S, Klemperer J, Barie PS. High-risk intrahospital transport of critically ill patients: safety and outcome of the necessary “road trip”. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1660–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199510000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Picetti E, Antonini MV, Lucchetti MC, Pucciarelli S, Valente A, Rossi I, et al. Intra-hospital transport of brain-injured patients: a prospective, observational study. Neurocrit Care. 2013;18:298–304. doi: 10.1007/s12028-012-9802-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papson JP, Russell KL, Taylor DM. Unexpected events during the intrahospital transport of critically ill patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:574–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.tb01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi HK, Shin SD, Ro YS, Kim DK, Shin SH, Kwak YH. A before- and after-intervention trial for reducing unexpected events during the intrahospital transport of emergency patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1433–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillman L, Leslie G, Williams T, Fawcett K, Bell R, McGibbon V. Adverse events experienced while transferring the critically ill patient from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:858–61. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.037697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuchelo LT, Chiavone PA. Intrahospital transport of patients on invasive ventilation: cardiorespiratory repercussions and adverse events. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35:367–74. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132009000400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day D. Keeping patients safe during intrahospital transport. Crit Care Nurse. 2010;30:18–33. doi: 10.4037/ccn2010446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovell MA, Mudaliar MY, Klineberg PL. Intrahospital transport of critically ill patients: complications and difficulties. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2001;29:400–5. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0102900412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barfod C, Lauritzen MMP, Danker JK, Sölétormos G, Forberg JL, Berlac PA, et al. Abnormal vital signs are strong predictors for intensive care unit admission and in-hospital mortality in adults triaged in the emergency department - a prospective cohort study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2012;20:28. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-20-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niegsch M, Fabritius ML, Anhøj J. Imperfect implementation of an early warning scoring system in a Danish teaching hospital: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kyriacos U, Jelsma J, James M, Jordan S. Monitoring vital signs: development of a modified early warning scoring (MEWS) system for general wards in a developing country. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee LLY, Lo WYL, Yeung KL, Kalinowski E, Tang SYH, Chan JTS. Risk stratification in providing inter-facility transport: experience from a specialized transport team. World J Emerg Med. 2010;1:49–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiegersma JS, Droogh JM, Zijlstra JG, Fokkema J, Ligtenberg JJM. Quality of interhospital transport of the critically ill: impact of a mobile intensive care unit with a specialized retrieval team. Crit Care. 2011;15:R75. doi: 10.1186/cc10064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Droogh JM, Smit M, Hut J, de Vos R, Ligtenberg JJM, Zijlstra JG. Inter-hospital transport of critically ill patients; expect surprises. Crit Care. 2012;16:R26. doi: 10.1186/cc11191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan E, MacDonald RD, Adhikari NKJ, Scales DC, Wax RS, Stewart TE, et al. Outcomes of interfacility critical care adult patient transport: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2006;10:R6. doi: 10.1186/cc3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Droogh JM, Smit M, Absalom AR, Ligtenberg JJM, Zijlstra JG. Transferring the critically ill patient: are we there yet? Crit Care. 2015;19:62. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0749-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanter RK, Tompkins JM. Adverse events during interhospital transport: physiologic deterioration associated with pretransport severity of illness. Pediatrics. 1989;84:43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seymour CW, Kahn JM, Schwab CW, Fuchs BD. Adverse events during rotary-wing transport of mechanically ventilated patients: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2008;12:R71. doi: 10.1186/cc6909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strauch U, Bergmans DCJJ, Winkens B, Roekaerts PMHJ. Short-term outcomes and mortality after interhospital intensive care transportation: an observational prospective cohort study of 368 consecutive transports with a mobile intensive care unit. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006801. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh JM, MacDonald RD, Bronskill SE, Schull MJ. Incidence and predictors of critical events during urgent air–medical transport. CMAJ. 2009;181:579–84. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura T, Fujino Y, Uchiyama A, Mashimo T, Nishimura M. Intrahospital transport of critically ill patients using ventilator with patient-triggering function. Chest. 2003;123:159–64. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waydhas C. Intrahospital transport of critically ill patients. Crit Care. 1999;3:R83–9. doi: 10.1186/cc362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keegan MT, Gajic O, Afessa B. Severity of illness scoring systems in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:163–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f96f81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Afessa B, Gajic O, Keegan MT. Severity of illness and organ failure assessment in adult intensive care units. Crit Care Clin. 2007;23:639–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallen E, Venkataraman ST, Grosso MJ, Kiene K, Orr RA. Intrahospital transport of critically ill pediatric patients. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1588–95. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199509000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang Y, Choi J, Kim D, Tudtud-Hans L, Li J, Michel A, et al. Clinical predictors of adverse outcome in severe sepsis patients with lactate 2–4 mM admitted to the hospital. QJM. 2015;108:279–87. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcu186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.González-Robledo J, Martín-González F, Moreno-García M, Sánchez-Barba M, Sánchez-Hernández F. Prognostic factors associated with mortality in patients with severe trauma: from prehospital care to the intensive care unit. Med Intensiva. 2015;39:412–21. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Xu X. Lactate clearance is a useful biomarker for the prediction of all-cause mortality in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2118–25. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Society of Critical Care Medicine, Chinese Medical Association. Chinese guidelines for the transport of critically ill patients, 2010 [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2010;22:328–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Weg JG, Haas CF. Safe intrahospital transport of critically ill ventilator-dependent patients. Chest. 1989;96:631–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kluge S, Baumann HJ, Kreymann G. Intrahospital transport of a patient with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease under noninvasive ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:886. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2626-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carteaux G, Lyazidi A, Cordoba-Izquierdo A, Vignaux L, Jolliet P, Thille AW, et al. Patient-ventilator asynchrony during noninvasive ventilation: a bench and clinical study. Chest. 2012;142:367–76. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ott LK, Hoffman LA, Hravnak M. Intrahospital transport to the radiology department: risk for adverse events, nursing surveillance, utilization of a MET and practice implications. J Radiol Nurs. 2011;30:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jradnu.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheck T, Kober A, Bertalanffy P, Aram L, Andel H, Molnár C, et al. Active warming of critically ill trauma patients during intrahospital transfer: a prospective, randomized trial. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:94–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03040703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quenot JP, Milési C, Cravoisy A, Capellier G, Mimoz O, Fourcade O, et al. Intrahospital transport of critically ill patients (excluding newborns) recommendations of the Societe de Reanimation de Langue Francaise (SRLF), the Societe Francaise d’Anesthesie et de Reanimation (SFAR), and the Societe Francaise de Medecine d’Urgence (SFMU) Ann Intensive Care. 2012;2:1. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists; Joint Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Minimum standards for intrahospital transport of critically ill patients. Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2003;15:202–4. [PubMed]

- 43.Blakeman TC, Branson RD. Inter- and intra-hospital transport of the critically ill. Respir Care. 2013;58:1008–23. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fanara B, Manzon C, Barbot O, Desmettre T, Capellier G. Recommendations for the intra-hospital transport of critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2010;14:R87. doi: 10.1186/cc9018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nuckols TK. Reducing the risks of intrahospital transport among critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2044–5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828fd714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]