Abstract

The up‐regulation of lectin‐like oxidized low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐1 (LOX‐1), encoded by the OLR1 gene, plays a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Moreover, OLR1 polymorphisms were associated with increased susceptibility to acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and coronary artery diseases (CAD). In these pathologies, the identification of therapeutic approaches that can inhibit or reduce LOX‐1 overexpression is crucial. Predictive analysis showed a putative hsa‐miR‐24 binding site in the 3′UTR of OLR1, ‘naturally’ mutated by the presence of the rs1050286 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). Luciferase assays revealed that miR‐24 targets OLR1 3′UTR‐G, but not 3′UTR‐A (P < 0.0005). The functional relevance of miR‐24 in regulating the expression of OLR1 was established by overexpressing miR‐24 in human cell lines heterozygous (A/G, HeLa) and homozygous (A/A, HepG2) for rs1050286 SNP. Accordingly, HeLa (A/G), but not HepG2 (A/A), showed a significant down‐regulation of OLR1 both at RNA and protein level. Our results indicate that rs1050286 SNP significantly affects miR‐24 binding affinity to the 3′UTR of OLR1, causing a more efficient post‐transcriptional gene repression in the presence of the G allele. On this basis, we considered that OLR1 rs1050286 SNP may contribute to modify OLR1 susceptibility to AMI and CAD, so ORL1 SNPs screening could help to stratify patients risk.

Keywords: Hsa‐mir‐24, OLR1 gene, acute myocardial infarction, Atherosclerosis, alternative splicing

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is characterized by the formation of plaques on the inner walls of arteries that threatens to become the leading cause of death worldwide via its sequelae of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and stroke. Many studies show that oxidized low‐density lipoproteins (ox‐LDL) play a key role in atherogenesis. Indeed, sub‐endothelial retention of ox‐LDL is considered the initial event of atherogenesis, followed by the infiltration and activation of inflammatory cells circulating in the blood 1. Lectin‐like oxidized low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐1 (LOX‐1) is the main ox‐LDL endothelial scavenger receptor (SR) 2 and the ox‐LDL/LOX‐1 interaction contributes to the triggering of endothelial dysfunction characteristic of atherosclerosis development 1. Moreover, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the OLR1 gene, encoding LOX‐1, have been associated with the risk of developing AMI 3, 4.

OLR1 (NM_002543) is subjected to alternative splicing generating two isoforms: Loxin (NM_001172633) 5 and OLR1D4 (NM_001172632). OLR1D4 lacks exon 4, so the putative encoded protein is shorter with a distinct C‐terminus. No other data are available for this isoform. On the contrary, Loxin, the splice isoform lacking exon 5, is well known and characterized 5, 6. It encodes for a truncated receptor (LOXIN) lacking two‐thirds of LOX‐1 functional lectin‐like binding domain. LOXIN forms heterodimers with LOX‐1 reducing the cells’ ability to bind ox‐LDL; when LOXIN is co‐expressed with LOX‐1, it is able to rescue cells from LOX‐1‐induced apoptosis in a dose‐dependent manner 6. Moreover, in vivo studies on animal models indicate that LOXIN expression induces a significant decrease in plaque coverage within the common carotid artery 7.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small single‐stranded non‐coding RNAs of 18–23 nucleotides, active in the regulation of gene expression both at transcriptional and post‐transcriptional levels. MicroRNAs, in fact, can block mRNA translation through a partial bond with complementary mRNA targets or determine a complete degradation when pairing is perfectly complementary 8.

Previous studies have described interactions among OLR1 and different miRNAs; within them, particularly interesting are hsa‐let7‐g 9 and hsa‐miR‐21 10 that are expressed mainly in endothelial cells and are associated with the apoptosis regulation.

To identify new miRNAs modulating the expression of OLR1 and its splice isoforms, we performed an in silico analysis searching for miRNA putative binding sites using popular miRNA target prediction algorithms (TargetScan and miRanda). Among the 89 putative miRNA binding sites identified, we functionally analysed and characterized the putative binding site for hsa‐miR‐24. In fact, the miR‐24 binding site, located in the 3′UTR of OLR1, contains a known SNP, rs1050286. Dual luciferase reporter assays showed that miR‐24 inhibited the expression of OLR1 by binding to the 3′UTR and that the inhibitory role of miR‐24 was impacted by rs1050286 SNP.

In addition, the functional relevance of miR‐24 in regulating physiologically OLR1 expression was established by miR‐24 overexpression studies in human cell lines heterozygous (A/G; i.e. HeLa) and homozygous (A/A; i.e. HepG2) for rs1050286 SNP. As expected, HeLa cells (A/G) showed a significant down‐regulation of OLR1 expression both at RNA and at protein level compared to HepG2 (A/A); moreover, the overexpression of miR‐24 in HeLa cells resulted in a decrement in cell proliferation rate.

Our results demonstrate that OLR1 is a new target of miR‐24 and that a genetic SNP (rs1050286) may disrupt miR‐24 binding site modulating OLR1 expression level. On this basis, we postulated that OLR1 rs1050286 SNP might contribute to modify OLR1 susceptibility to AMI and CAD.

Even if these data may be validated by additional studies, they suggest that OLR1 rs1050286 SNP screening could help to stratify patient risk.

Materials and methods

miRNA putative binding sites in silico analysis

In silico analysis were performed on the coding sequence and 3′UTR of OLR1 gene using TargetScan v6.0 (http://www.targetscan.org/) and miRanda (http://www.microrna.org/) software. All algorithms were run with default parameters. TargetScan predictions were evaluated on genomic multiple alignments of human, mouse, rat, cow, dog and chicken, imposing conservation in at least five species. The TargetScan context component of the score was ignored for the predictions in the coding sequence.

Luciferase reporter assays

The 3′UTR of OLR1 containing the putative miR‐24 binding site (G) and the ‘naturally’ mutated site (A) were amplified from genomic GM06991 and GM07053B clones, respectively, and the PCR products were XhoI/NotI digested and subcloned in psiCHECK‐2 vector immediately downstream of the Renilla Luciferase gene. The Firefly Luciferase gene reporter was used as control for transfection efficiency. pEFDEST51 premiR‐24‐2 vector was used to overexpress miR‐24 11. About 2 × 106 cells have been plated in a 60‐mm Petri dish and transfected with a total of 5 μg of DNA (for the cotransfection, we used 2.5 μg of each plasmid) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). After 24 hrs, a luciferase assay was conducted using Dual Glo® Luciferase Assay (Promega Fitchburg, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

OLR1 SNP rs1050286 genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted following the Flexigene Kit protocol (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A TaqMan® Genotyping Assay protocol (C_7433809_30; Life Technologies, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to analyse rs1050286 SNP in HeLa and HepG2 cell lines.

Cell culture and miRNA overexpression

HeLa and HepG2 cell lines (ATCC) were cultured in complete medium DMEM supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 1× L‐glutamine, 1× Fungizone at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were seeded in triplicate at a 25,000 cell/cm2 density and grown in complete culture medium. Both cell lines were transiently transfected by using Calcium Phosphate Transfection Kit (Invitrogen) with 5 μg of pEFDEST51 premiR‐24‐2 vector and pEGFPN‐1 as control. Cells were harvested 48 and 72 hrs after transfection and suspended in 1 ml of Trizol (Ambion Foster City, CA, USA) (until RNA extraction) for qRT‐PCR assay and fixed in buffered formalin for immunocytochemistry.

Quantitative real time PCR

Total RNA from transfected cells was treated with DNAse (2 U/μl; Ambion) and then retrotranscribed by using ‘High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit’ (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). A qRT‐PCR (SYBR Green assay Applied Biosystems) assay was performed with different primers pairs, designed using the software Primer Blast, specific for each OLR1 isoforms: OLR1 (F: 5′‐GCACAGCTGATCTGGACTTCAT‐3′, R: 5′‐CCCCATCCAGAATGGAAAACT‐3′), LOXIN (F: 5′‐AAAAGAGCCAAGAGAAGTGCTTGT‐3′, R: 5′‐TCTAAATCAGATCAGCTGTGC‐3′) and OLR1D4 (F: 5′‐TTGTTCAGGACTTCATCCAGC‐3′, R: 5′‐TCGGACTCTAAATAAGTGGGG‐3′). RPL37A and β‐actin genes were used for data normalization.

Western Blot analysis

Standard protein extraction was performed with RIPA lysis buffer. Denatured protein extracts (35 μg) were loaded on a 10% SDS‐PAGE. Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Hybond‐P; Amersham‐Pharmacia Biotech, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Amersham Place, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). Membranes were stained with Ponceau S dye, to check for equal loading and homogeneous transfer and incubated for 1 hr at RT with 3% skim milk (Difco Lab., Detroit, MI, USA) and 0.5% Tween 20 (USB, Cleveland, OH, USA). The membrane was incubated with anti‐LOX‐1 rabbit policlonal (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti‐β‐actin mouse IgG1 monoclonal antibody (Sigma‐Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). Horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated antibodies were used as secondary antibodies. Signals were detected by the SuperSignal‐detection method (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and quantified by densitometry (GeneGnome; SynGene, Bangalore, Karnataka, India) after normalization for β‐actin gene product. All the experiments were repeated three times and gave similar results.

Immunocytochemistry

An anti‐LOX‐1 antibody (R&D, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used to evaluate LOX‐1 expression. To assess the background staining, a negative control was carried out without addition of primary antibody. Secondary antibody (Biotinylated goat anti‐rabbit IgG) and following reagents (HRP‐conjugated streptavidin) were added. After washing, slides were incubated with diaminobenzidine and counterstained with haematoxylin.

Proliferation assay

Transfected cells, seeded in triplicate, at a density of 6 × 103 cells/cm2, were counted after 24, 48, 72 and 96 hrs. Trypan blue staining was performed to evaluate cell death percentage. The cell suspension was transferred to a haemocytometer for cell counting.

Statistical analysis

Each analysis was performed in triplicate and data are expressed as mean values ± SD. Student's t‐test was used to compare two groups. A P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

An in silico analysis using miRanda and TargetScan programs was conducted on the entire coding sequence and 3′UTR of OLR1 and its splice isoforms to identify new miRNAs binding sites. A total of 89 miRNA putative binding sites (Table 1) potentially interacting with OLR1 were identified. To find known SNPs that could modulate miRNA/OLR1 gene pairing we analysed them in the miR‐SNP database (http://www.bioguo.org/miRNASNP/). Twenty‐three miRNAs presented SNPs in the binding region (Table 1, in bold).

Table 1.

List of the 89 putative miRNAs identified on coding and 3′UTR sequences of OLR1. The start and end position of each seed region are indicated. In bold are shown the 23 miRNAs containing a known SNP in the seed region

| miRNAs | OLR1 (NM_002543) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start match | End match | TargetScan Score | miRanda Score | |

| hsa‐miR‐298 | 35 | 42 | −0.357 | 145 |

| hsa‐miR‐3158‐5p | 37 | 44 | −0.373 | 143 |

| hsa‐miR‐4274 | 77 | 83 | −0.23 | 142 |

| hsa‐miR‐4693‐3p | 85 | 91 | −0.283 | 155 |

| hsa‐miR‐767‐5p | 274 | 280 | −0.23 | 159 |

| hsa‐miR‐3065‐3p | 276 | 282 | −0.233 | 155 |

| hsa‐miR‐4266 | 309 | 316 | −0.366 | 142 |

| hsa‐miR‐1258 | 311 | 318 | −0.287 | 153 |

| hsa‐miR‐3152‐3p | 313 | 320 | −0.25 | 142 |

| hsa‐miR‐581 | 316 | 323 | −0.279 | 149 |

| hsa‐miR‐4464 | 329 | 336 | −0.237 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐4299 | 339 | 346 | −0.361 | 142 |

| hsa‐miR‐345 | 403 | 410 | −0.325 | 155 |

| hsa‐miR‐615‐3p | 442 | 448 | −0.265 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐876‐5p | 459 | 466 | −0.257 | 147 |

| hsa‐miR‐3167 | 459 | 466 | −0.278 | 140 |

| hsa‐miR‐4456 | 486 | 493 | −0.439 | 140 |

| hsa‐miR‐620 | 500 | 507 | −0.316 | 147 |

| hsa‐miR‐1270 | 500 | 507 | −0.327 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐432 | 502 | 509 | −0.4 | 147 |

| hsa‐miR‐4754 | 545 | 552 | −0.569 | 150 |

| hsa‐miR‐194 | 576 | 582 | −0.246 | 140 |

| hsa‐miR‐4642 | 640 | 647 | −0.336 | 140 |

| hsa‐miR‐198 | 675 | 681 | −0.233 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐1287 | 687 | 692 | −0.356 | 147 |

| hsa‐miR‐3151 | 786 | 792 | −0.339 | 150 |

| hsa‐miR‐3917 | 802 | 808 | −0.295 | 157 |

| hsa‐miR‐3192 | 816 | 823 | −0.344 | 151 |

| hsa‐miR‐4268 | 857 | 863 | −0.233 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐718 | 871 | 877 | −0.242 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐3614‐3p | 941 | 947 | −0.256 | 168 |

| hsa‐miR‐520a‐5p | 946 | 953 | −0.308 | 140 |

| hsa‐miR‐525‐5p | 946 | 953 | −0.318 | 146 |

| hsa‐miR‐96 | 1012 | 1019 | −0.315 | 141 |

| hsa‐miR‐1271 | 1012 | 1019 | −0.336 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐4674 | 1025 | 1031 | −0.264 | 140 |

| hsa‐miR‐378g | 1026 | 1033 | −0.384 | 141 |

| hsa‐miR‐1184 | 1051 | 1058 | −0.35 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐544 | 1066 | 1073 | −0.244 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐4755‐3p | 1088 | 1095 | −0.446 | 150 |

| hsa‐miR‐1302 | 1147 | 1154 | −0.364 | 146 |

| hsa‐miR‐4298 | 1147 | 1154 | −0.385 | 157 |

| hsa‐miR‐1207‐5p | 1159 | 1166 | −0.474 | 172 |

| hsa‐miR‐4763‐3p | 1159 | 1166 | −0.421 | 156 |

| hsa‐miR‐498 | 1217 | 1224 | −0.281 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐1248 | 1376 | 1383 | −0.238 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐4757‐5p | 1385 | 1392 | −0.403 | 151 |

| hsa‐miR‐140‐3p | 1455 | 1461 | −0.262 | 161 |

| hsa‐miR‐4451 | 1473 | 1480 | −0.382 | 154 |

| hsa‐miR‐3120‐5p | 1489 | 1496 | −0.267 | 161 |

| hsa‐miR‐3120‐5p | 1493 | 1500 | −0.3 | 161 |

| hsa‐miR‐3120‐5p | 1497 | 1505 | −0.312 | 161 |

| hsa‐miR‐4286 | 1539 | 1546 | −0.375 | 140 |

| hsa‐miR‐4674 | 1545 | 1552 | −0.378 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐635 | 1547 | 1554 | −0.433 | 143 |

| hsa‐miR‐4752 | 1592 | 1599 | −0.326 | 143 |

| hsa‐miR‐4795‐5p | 1607 | 1613 | −0.234 | 152 |

| hsa‐miR‐4650‐3p | 1644 | 1651 | −0.379 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐3909 | 1651 | 1658 | −0.364 | 142 |

| hsa‐miR‐3611 | 1676 | 1683 | −0.284 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐3153 | 1736 | 1742 | −0.246 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐1253 | 1770 | 1777 | −0.272 | 150 |

| hsa‐miR‐567 | 1806 | 1813 | −0.242 | 140 |

| hsa‐miR‐297 | 1807 | 1814 | −0.286 | 144 |

| hsa‐miR‐643 | 1809 | 1816 | −0.23 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐4658 | 1831 | 1838 | −0.337 | 140 |

| hsa‐miR‐4777‐5p | 1838 | 1845 | −0.266 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐4481 | 1936 | 1942 | −0.265 | 146 |

| hsa‐miR‐4745‐5p | 1936 | 1942 | −0.265 | 140 |

| hsa‐miR‐24 | 1942 | 1964 | −0.267 | 141 |

| hsa‐miR‐516a‐3p | 1965 | 1971 | −0.265 | 157 |

| hsa‐miR‐3944‐5p | 1983 | 1990 | −0.503 | 151 |

| hsa‐miR‐3074‐5p | 1998 | 2004 | −0.254 | 157 |

| hsa‐miR‐4639‐3p | 2172 | 2179 | −0.419 | 141 |

| hsa‐miR‐3201 | 2181 | 2188 | −0.319 | 140 |

| hsa‐miR‐4791 | 2181 | 2188 | −0.351 | 154 |

| hsa‐miR‐3134 | 2184 | 2191 | −0.356 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐4459 | 2214 | 2221 | −0.33 | 144 |

| hsa‐miR‐4667‐5p | 2229 | 2236 | −0.376 | 158 |

| hsa‐miR‐4700‐5p | 2229 | 2236 | −0.366 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐876‐3p | 2238 | 2245 | −0.371 | 147 |

| hsa‐miR‐518a‐5p | 2327 | 2333 | −0.237 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐527 | 2327 | 2333 | −0.237 | NA |

| hsa‐miR‐4534 | 2357 | 2363 | −0.253 | 141 |

| hsa‐miR‐4272 | 2395 | 2402 | −0.253 | 142 |

| hsa‐miR‐4506 | 2434 | 2440 | −0.283 | 146 |

| hsa‐miR‐4733‐5p | 2473 | 2480 | −0.393 | 161 |

| hsa‐miR‐646 | 2491 | 2497 | −0.283 | 143 |

| hsa‐miR‐578 | 2512 | 2518 | −0.261 | NA |

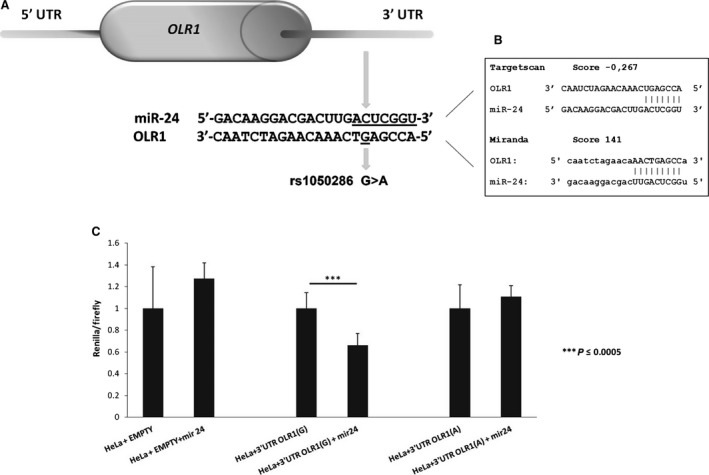

Among them, rs1050286 SNP (G>A), mapping in the 3′UTR of the OLR1 gene, is located within the seed‐binding region for hsa‐miR‐24 (Fig. 1A and B).

Figure 1.

Effect of miR‐24 overexpression on OLR1 3′ UTR luciferase activity. (A) A graphic representation of miR‐24 binding site on OLR1 3′UTR. The miR‐24 seed region is underlined. The position of SNP rs 1050286 is shown. (B) Prediction scores of the interaction between OLR1 and miR‐24 by TargetScan and miRanda software. (C) Luciferase assay results. Data were normalized to Firefly luciferase activity and to cells transfected with control vectors (empty psiCHECK‐2 or 3′UTR(G) alone or 3′UTR(A) alone). Error bars represent standard deviation of technical repeat experiments (n = 3).

To test the interaction between OLR1 3′UTR and miR‐24, we performed an in vitro luciferase assay. HeLa cells transfected with a plasmid expressing OLR1 3′UTR with a conserved hsa‐miR‐24 seed region (i.e. containing G nucleotide) showed a significant (P < 0.0005) reduction in luciferase level; on the contrary, luciferase level did not change when the same cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing mutated 3′UTR (containing A nucleotide) (Fig. 1C). These results confirm that OLR1 is a bona fide miR‐24 target. Moreover, this functional analysis proved that the rs1050286 G‐allele leads to a significant lower luciferase activity (P < 0.0005), compared with the A allele, thus demonstrating that in vitro interaction among miR‐24 and OLR1 is impaired by rs1050286 SNP.

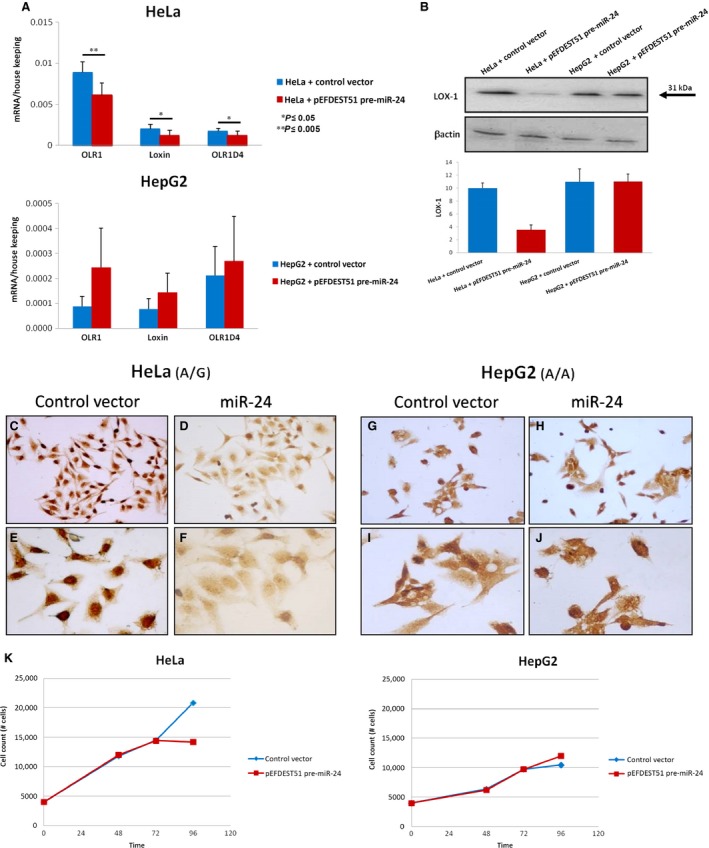

To confirm miR‐24/OLR1 binding, we analysed OLR1 and its splice isoform expression (mRNA and protein) in two human cell lines with different genotype (A/G versus A/A) both at 48 hrs and at 72 hrs after miR‐24 transfection. Although 48 hrs after transfection we did not observe significant changes in OLR1 mRNA and protein levels (data not shown), 72 hrs post transfection, HeLa cells (A/G) overexpressing miR‐24 showed a significant OLR1 (and its splice isoforms) mRNA decrease compared to cells transfected with control vector (Fig. 2A). Accordingly, LOX‐1 protein level decreased to about 65% in HeLa overexpressing miR‐24 (Fig. 2B). LOX‐1 down‐regulation by miR‐24 was also evident using Immunocytochemistry experiments (Fig. 2C–F). On the contrary, OLR1 and its splice isoform expression level (both mRNA and protein) did not change in HepG2 (A/A) after miR‐24 overexpression (Fig. 2A, B, G–J).

Figure 2.

LOX‐1 expression in HeLa and HepG2 cells is modulated by miR‐24 overexpression and rs1050286 SNP. (A) qRT‐PCR results. (B) Western blot analysis. Bar graphs show the ratio of LOX‐1 to β‐actin. The experiments were repeated three times and the data show the representative results. (C–K) Immunocytochemistry results. (C, E, G, I) Control plasmid; (D, F, H, J) miR‐24 transfected cells. (C, D, G, H) 20× magnification; (E, F, I, J) 40× magnification. (K) HeLa and HepG2 proliferation assay.

Interestingly, 96 hrs after seeding the overexpression of miR‐24 inhibits cell growth in HeLa cells with respect to the same cell line transfected with the empty plasmid, whereas cell growth did not change in HepG2 cells overexpressing miR‐24 compared to the same cells transfected with empty vector (P < 0.01, Fig. 2K).

Discussion

LOX‐1, encoded by the OLR1 gene, is the major endothelial receptor for ox‐LDL and plays a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis 1, 2, 4. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that normal LOX‐1 activity is essential for maintaining the structural integrity of tissues; in fact, an increased activity of LOX‐1 is associated with cancer cell invasion 12.

OLR1 is a spliced gene and its alternative splicing is regulated by six intronic SNPs spanning from intron 4 to 3′UTR; these SNPs are in linkage disequilibrium and related to a higher risk of developing AMI 3, 4. In fact, a specific haplotype (5′‐CTGGTT‐3′) correlates with a OLR1/LOXIN ratio 33% higher than those identified in individuals carrying another haplotype (5′‐GCAAGC‐3′), and the 5′‐CTGGTT‐3′ haplotype was significantly associated with CAD and myocardial infarction 3, 5.

Based on this and other data, LOX‐1 is generally considered a promising therapeutic target for both atherosclerosis and cancer 13.

Therefore, to identify molecular factors that may regulate the OLR1 expression, we performed an in silico analysis on the coding sequence and 3′UTR of OLR1 gene to search putative miRNA binding sites. As functional polymorphisms in 3′UTRs of several genes have been reported to be associated with diseases by affecting gene expression, we searched for SNPs, in the coding sequence and in the UTRs of OLR1, which map in the identified miRNA putative binding sites. We found a putative hsa‐miR‐24 binding site that is ‘naturally’ mutated, inside its seed region, by a common SNP (rs1050286) (Fig. 1). In fact, in the European population the frequency of the G allele, that results in a conserved miR‐24 seed region, is 0.483, whereas the A allele has a frequency of 0.517. However, in black/African‐Americans and in East Asians the G allele has a frequency of 0.233 (dbSNP, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

In vitro luciferase assay and overexpression studies demonstrate an interaction among miR‐24 and OLR1 and also that rs1050286 alters the binding affinity between miR‐24 and its 3′UTR, thus reducing the suppression of OLR1 expression.

miR‐24 is commonly considered as a multifunctional cardio‐miR that plays good and bad roles in heart; in fact, it protects cardiomyocytes from apoptosis and reduces cardiac fibrosis, but inhibits angiogenesis and deteriorates heart failure 14. Moreover, miR‐24 is up‐regulated in the chronic phase after myocardial infarction and promotes hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes in mouse model experiments and the cardiac overexpression of miR‐24 resulted in scar size reduction and heart function improvement 15. Our findings suggest that the rs1050286 SNP in the OLR1 3′UTR, by disrupting the regulatory role of miR‐24 on OLR1 expression, may contribute to the occurrence of atherosclerosis. Moreover, these results highlight the importance of genotype‐dependent differential microRNA regulation in relation to human disease risk.

Finally, these evidence suggest that OLR1 could be a new therapeutic target for miR‐24 and represent a starting point for the development of possible therapeutic strategies against diseases related to OLR1 overexpression.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose relevant to the contents of this paper. The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

E.M. and F.A. designed the research study; E.M, B.R and S.P. performed the research; F.F. and H.C.M analysed the data; G.N. and D.C. contributed essential reagents or tools; E.M., G.N. and F.A. wrote the paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from Fondazione Roma (Non Communicable Diseases, NCDs: Development of a integrated protocol based on environmental and genetic/epigenetic data for the risk prediction of AMI in patients with coronary atherosclerosis) to G.N. and by the Lazio Regional Municipality (Agreement CRUL‐Lazio n. 7 12650/2010) PhD scholarship to E.M. We are grateful to Dr. Li Qian for kindly supporting pEFDEST51 premiR‐24‐2 vector.

References

- 1. Pirillo A, Norata GD, Catapano AL. LOX‐1, OxLDL, and atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2013; 2013: 152786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sawamura T, Kume N, Aoyama T, et al An endothelial receptor for oxidized low‐density lipoprotein. Nature. 1997; 386: 73–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mango R, Clementi F, Borgiani P, et al Association of a single nucleotide polymorphisms in the oxidized LDL receptor 1 (OLR1) gene in patients with acute myocardical infarction. J Med Genet. 2003; 40: 933–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Novelli G, Mango R, Vecchione L, et al New insights in atherosclerosis research. LOX‐1, leading actor of cardiovascular diseases. Clin Ter. 2007; 158: 239–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mango R, Biocca S, Del Vecchio F, et al In vivo and in vitro studies support that a new splicing isoform of OLR1 gene is protective against acute myocardical infarction. Circ Res. 2005; 97: 152–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Biocca S, Filesi I, Mango R, et al The splice variant LOXIN inhibits LOX‐1 receptor function through hetero‐oligomerization. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008; 44: 561–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. White SJ, Sala‐Newby GB, Newby AC. Over‐expression of scavenger receptor LOX‐1 in endothelial cells promotes atherogenesis in the ApoE(‐/‐) mouse model. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2011; 20: 369–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ying SY, Chang DC, Lin SL. The microRNA (miRNA): overview of the RNA genes that modulate gene function. Mol Biotechnol. 2008; 38: 257–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ding Z, Wang X, Schnackenberg L, et al Regulation of autophagy and apoptosis in response to ox‐LDL in vascular smooth muscle cells, and the modulatory effects of the microRNA hsa‐let‐7g. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 168: 1378–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khaidakov M, Mehta JL. Oxidized LDL triggers pro‐oncogenic signaling in human breast mammary epithelial cells partly via stimulation of MiR‐21. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7: e46973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Qian L, Van Laake LW, Huang Y, et al miR‐24 inhibits apoptosis and represses Bim in mouse cardiomyocytes. J Exp Med. 2011; 208: 549–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hirsch HA, Iliopoulos D, Joshi A, et al A transcriptional signature and common gene networks link cancer with lipid metabolism and diverse human diseases. Cancer Cell. 2010; 17: 348–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ulrich‐Merzenich G, Zeitler H. The lectin‐like oxidized low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐1 as therapeutic target for atherosclerosis, inflammatory conditions and longevity. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013; 17: 905–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Katoh M. Cardio‐miRNAs and onco‐miRNAs: circulating miRNA‐based diagnostics for non‐cancerous and cancerous diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2014; 2: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guo C, Deng Y, Liu J, et al Cardiomyocyte‐specific role of miR‐24 in promoting cell survival. J Cell Mol Med. 2014; 20: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]