Abstract

Background:

Decreased platelet (PLT) count is one of the independent risk factors for mortality in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. This study was to investigate the relationship between PLT indices and illness severity and their performances in predicting hospital mortality.

Methods:

Adult patients who admitted to ICU of Changzheng Hospital from January 2011 to September 2012 and met inclusion criteria were included in this study. Univariate analysis was used to identify potential independent risk factors for mortality. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to calculate adjusted odds ratio for mortality in patients with normal or abnormal PLT indices. The relationship between PLT indices and illness severity were assessed by the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) scores or sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores in patients with normal and abnormal PLT indices. The performances of PLT indices in predicting mortality were assessed by receiver operating curves and diagnostic parameters. The survival curves between patients with normal and abnormal PLT indices were compared using Kaplan–Meier method.

Results:

From January 2011 to September 2012, 261 of 361 patients (204 survivors and 57 nonsurvivors) met the inclusion criteria. After adjustment for clinical variables, PLT count <100 × 1012/L (P = 0.011), plateletcrit (PCT) <0.108 (P = 0.002), mean platelet volume (MPV) >11.3 fL (P = 0.023) and platelet distribution width (PDW) percentage >17% (P = 0.009) were identified as independent risk factors for mortality. The APACHE II and SOFA scores were 14.0 (9.0–20.0) and 7.0 (5.0–10.5) in the “low PLT” tertile, 13.0 (8.0–16.0) and 7.0 (4.0–11.0) in the “low PCT” tertile, 14.0 (9.3–19.0) and 7.0 (4.0–9.8) in the “high MPV” tertile, 14.0 (10.5–20.0) and 7.0 (5.0–11.0) in the “high PDW” tertile, all of which were higher than those in patients with normal indices. Patients with decreased PLT and PCT values (all P < 0.001), or increased MPV and PDW values (P = 0.007 and 0.003, respectively) had shortened length of survival than those with normal PLT indices.

Conclusions:

Patients with abnormally low PLT count, high MPV value, and high PDW value were associated with more severe illness and had higher risk of death as compared to patients with normal PLT indices.

Keywords: Mean Platelet Volume, Platelet Count, Platelet Distribution Width, Platelet Indices, Plateletcrit

INTRODUCTION

Platelet (PLT), a major and essential constituent of blood, plays an important role in physiological and pathological processes such as coagulation, thrombosis, inflammation and maintenance the integrity of vascular endothelial cells.[1,2,3] PLT indices are a group of parameters that are used to measure the total amount of PLTs, PLTs morphology and proliferation kinetics.[4] The commonly used PLT indices include PLT count, mean platelet volume (MPV), platelet distribution width (PDW), and plateletcrit (PCT).[5] The MPV refers to the ratio of PCT to PLT count. PDW is numerically equal to the coefficient of PLT volume variation, which is used to describe the dispersion of PLTs volume.[5]

Originally, these indices have been applied in the diagnosis of hematological system diseases. Recently, it has been discovered that these indices are related to the severity of illness and patients’ prognosis. A reduction in PLT count is an independent risk factor for critically ill patients in intensive care unit (ICU).[6] In addition, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) System also includes thrombocytopenia as an independent risk factor for mortality.[7] However, whether other PLT indices are associated with the severity of illness and patients’ prognosis is still under exploring. In a recent research, it was reported that MPV was rising synchronously with interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein in septic premature infants, and the increment was correlated to the severity of sepsis.[8] In addition, in patients with cirrhosis and ascites, elevated PDW and MPV were accurate diagnostic predictors for ascitic fluid infection.[9] In addition, elevated PDW and MPV were associated with higher risk of in-hospital cardiovascular adverse events in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention.[10] All these evidences indicated that PLT indices may be treated as indictors in a series of diseases. Thus, we conducted a retrospective study, which included patients who admitted to our ICU from January 2011 to September 2012, to explore whether PLT indices (PLT, PCT, MPV, and PDW) could be used to determine the severity of illness and to predict death events in critically ill patients.

METHODS

Patients

Patients who admitted to ICU of Changzheng Hospital from January 2011 to September 2012 were included. The general conditions, diagnosis at admission, laboratory examinations, treatment measures, length of ICU stay, outcomes, and other data regarding patients’ in-hospital information were obtained from the Electronic Medical Records System. Only the data and the illness severity scores recorded at admission were used for analysis. In cases when patients admitted into hospital multiple times, only the data drew from the first record was considered.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

(1) Age ranged from 18 to 75 years; (2) all PLT indices and in-hospital information were fully available; (3) the length of stay in ICU was more than 24 h.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Pregnant and maternity women; (2) patients with active hemorrhage; (3) patients with hematological diseases (including anemia, hypersplenia, lymphoma or leukemia, rheumatism, and bone marrow diseases); (4) patients who had infused with blood or PLTs prior to their admission; (5) patients who had used anti-PLT drugs such as clopidogrel prior to their admission; (6) patients who had received radiotherapy or chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation 1 month prior to admission.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Military Medical University and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or legal representatives.

Assessment of outcomes

The assessment of outcomes included: (1) The odds ratio (OR) for mortality in patients with normal and abnormal PLT indices; (2) the relationship between all PLT indices and the APACHE II scores or sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores; (3) the performance of received operating curves (ROCs) of all PLT indices in predicting patients’ death events; (4) the difference of survival curves between patients with normal and abnormal PLT indices.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and comparisons between groups were performed using a Student's t-test. Abnormally distributed data were expressed as median and interquartile range (M, IQR), and comparisons between groups were performed using a Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical variables were presented as numerical data and percentages, statistical comparisons were conducted by a Chi-square (χ2) test. In univariate analysis, variables with P < 0.1 between survivals and deaths were considered as potential risk factors for mortality and included into a multivariable logistic regression model for adjustment. After every PLT index had been adjusted by clinical covariates, the ORs for mortality in patients with normal or abnormal PLT indices were presented. Hosmer-Lemeshow test was applied to test Goodness-of-fit properties. Collinearity was determined by variance inflation factor (VIF). The value of VIF more than 5 indicated the existence of multicollinearity.[11] Second, to explore the relationship between PLT indices and illness severity, we first divided each PLT index into tertiles of the normal range, higher than upper limit, lower than lower limit. Then, we plotted the distribution of APACHE II scores and SOFA scores in each tertile to investigate whether the patients with abnormal PLT indices were associated with higher illness scores. Third, to evaluate the performance of the PLT indices in predicting death events, we built the ROCs for every index and compared the area under the curves (AUC). We also calculated optimal cut-off point (where the Youden index reached the maximum value)[12] and the diagnostic parameters including sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio and diagnostic accuracy for each PLT index. Finally, to compare the prognosis in patient with normal and abnormal PLT indices, we used the Kaplan–Meier method to construct survival curves for the each group. Log-rank test was used for comparison of different survival curves between patients with normal and abnormal PLT indices. All the statistical analysis was performed using Stata10 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All the diagrams were constructed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA).

RESULTS

General information of patients

A total of 361 patients were admitted to ICU from January 2011 to September 2012, of which 261 patients met the inclusion criteria. The clinical characteristics of the survival group and the death group were summarized in Table 1. There were 191 male patients and 70 female patients, and their death rates were 18.3% and 31.4%, respectively. Respiratory disease (25.7%), trauma (12.3%) and cardiovascular disease (10.0%) were the most common etiology among all the patients. Patients who died in hospital were elder (P = 0.002) and had higher APACHE II and SOFA scores (P < 0.001) than survivors. Among laboratory examinations, serum creatinine and serum lactate were significantly higher in death patients than survivors (P < 0.001 and P = 0.001, respectively). Among the four PLT indices, PLT and PCT were lower in death patients (P = 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively) while MPV and PDW were higher in the death patients (P = 0.011 and P < 0.001, respectively).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients on admission by survivors and death

| Variables | Survivors (n = 204) | Nonsurvivors (n = 57) | Total (n = 261) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 156 (76.5) | 35 (61.4) | 191 (73.2) | 0.023 |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 52 (43–61) | 64 (53–76) | 57 (46–65) | 0.002 |

| APACHE II scores, median (IQR) | 11 (8–16) | 18 (13–25.5) | 12 (9–18) | <0.001 |

| SOFA scores, median (IQR) | 5 (3–8) | 9 (7–14) | 6 (3–8) | <0.001 |

| Etiology, n (%) | ||||

| Cardiovascular | 21 (10.3) | 5 (8.8) | 26 (10.0) | >0.05 |

| Pulmonary | 54 (26.5) | 13 (22.8) | 67 (25.7) | >0.05 |

| Neurological | 20 (9.8) | 5 (8.8) | 25 (9.6) | >0.05 |

| Renal failure | 8 (3.9) | 3 (5.3) | 11 (4.2) | >0.05 |

| Hepatic failure | 8 (3.9) | 2 (3.5) | 10 (3.8) | >0.05 |

| Digestive | 8 (3.9) | 3 (5.3) | 11 (4.2) | >0.05 |

| Endocrine | 5 (2.5) | 2 (3.5) | 7 (2.7) | >0.05 |

| Multiple organ failure | 18 (8.8) | 5 (8.7) | 23 (8.8) | >0.05 |

| Trauma | 25 (12.3) | 7 (12.3) | 32 (12.3) | >0.05 |

| Shock | 14 (6.9) | 5 (8.8) | 19 (7.3) | >0.05 |

| Sepsis | 17 (8.3) | 5 (8.8) | 22 (8.4) | >0.05 |

| Unclassified | 6 (2.9) | 2 (3.5) | 8 (3.1) | >0.05 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 89 (43.6) | 36 (63.1) | 125 (47.9) | 0.013 |

| Laboratory examinations, mean ± SD | ||||

| WBC count, ×109/L | 9.2 ± 5.6 | 10.6 ± 6.3 | 9.5 ± 5.8 | >0.05 |

| Total bilirubin, µmol/L | 22.7 ± 28.1 | 31.2 ± 39.8 | 24.6 ± 31.0 | >0.05 |

| Urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 6.7 ± 8.9 | 9.3 ± 12.3 | 7.3 ± 9.7 | >0.05 |

| Serum creatinine, µmol/L | 73.2 ± 89.7 | 123.7 ± 196.3 | 84.2 ± 121.3 | 0.006 |

| Blood lactic acid, mmol/L | 2.3 ± 3.6 | 4.3 ± 6.7 | 2.7 ± 4.5 | 0.003 |

| Platelet indices, mean ± SD | ||||

| PLT, ×109/L | 196.5 ± 103.3 | 141.1 ± 48.3 | 178.5 ± 100.6 | <0.001 |

| PCT | 0.26 ± 0.20 | 0.17 ± 0.09 | 0.22 ± 0.18 | 0.001 |

| MPV, fL | 12.8 ± 8.5 | 15.8 ± 4.3 | 13.4 ± 7.9 | 0.011 |

| PDW, % | 14.5 ± 3.2 | 17.0 ± 4.4 | 15.0 ± 3.6 | <0.001 |

Characteristics and clinical information of patients on admission were obtained from EMRS. IQR: Interquartile range; APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; SOFA: Sequential organ failure assessment; SD: Standard deviation; WBC: White blood cell; PLT: Platelet count; PCT: Plateletcrit; MPV: Mean platelet volume; PDW: Platelet distribution width percentage; EMRS: Electronic Medical Records System.

Adjusted odds ratio of abnormal platelet indices in multivariate regression model

As the results of univariate analysis presented in Table 1, gender, age, APACHE II, SOFA scores, mechanical ventilation, blood lactic acid, serum creatinine and all PLT indices were selected as potential risk factors for death and entered in the multivariate analysis. After adjustment for well-established clinical risk factors, PLT <100 × 1012/L (OR: 1.96 [1.21–2.32], P = 0.011), PCT < 0.108 (OR: 1.97 [1.60–2.09], P = 0.002), MPV >11.3 fL (OR: 1.15 [1.02–2.36], P = 0.023) and PDW >17% (OR: 2.38 [1.14–4.99], P = 0.009) were identified as the independent risk factors for mortality [Table 2].

Table 2.

The ORs of platelet indices for mortality after adjustment

| Platelet indices | OR | 95% CI | P for OR | P of Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLT, ×1012/L | 0.683 | |||

| 100–300 (reference) | 1 | – | – | |

| <100 | 1.96 | 1.21–2.32 | 0.011 | |

| >300 | 0.86 | 0.56–3.41 | 0.998 | |

| PCT | 0.559 | |||

| 0.108–0.282 (reference) | 1 | |||

| <0.108 | 1.97 | 1.60–2.09 | 0.002 | |

| >0.282 | 0.81 | 0.62–3.21 | 0.162 | |

| MPV, fL | 0.721 | |||

| 7.7–11.3 (reference) | 1 | – | – | |

| <7.7 | 1.21 | 0.13–10.21 | 0.897 | |

| >11.3 | 1.15 | 1.02–2.36 | 0.023 | |

| PDW, % | 0.530 | |||

| 10–17 (reference) | 1 | – | – | |

| <10 | 1.70 | 0.34–3.37 | 0.511 | |

| >17 | 2.38 | 1.14–4.99 | 0.009 |

Platelet indices were divided into three tertiles of lower than low limit, higher than up limit and normal range as presented in table. The normal range was considered as reference. ORs were adjusted for variables including gender, age, APACHE II, SOFA scores, mechanical ventilation, blood lactic acid, serum creatinine. PLT: Platelet; PCT: Plateletcrit; MPV: Mean platelet volume; PDW: Platelet distribution width percentage; ORs: Odds ratios; CI: Confidence interval; APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; SOFA: Sequential organ failure assessment.

The receiver operating curves of platelet indices on predicting mortality

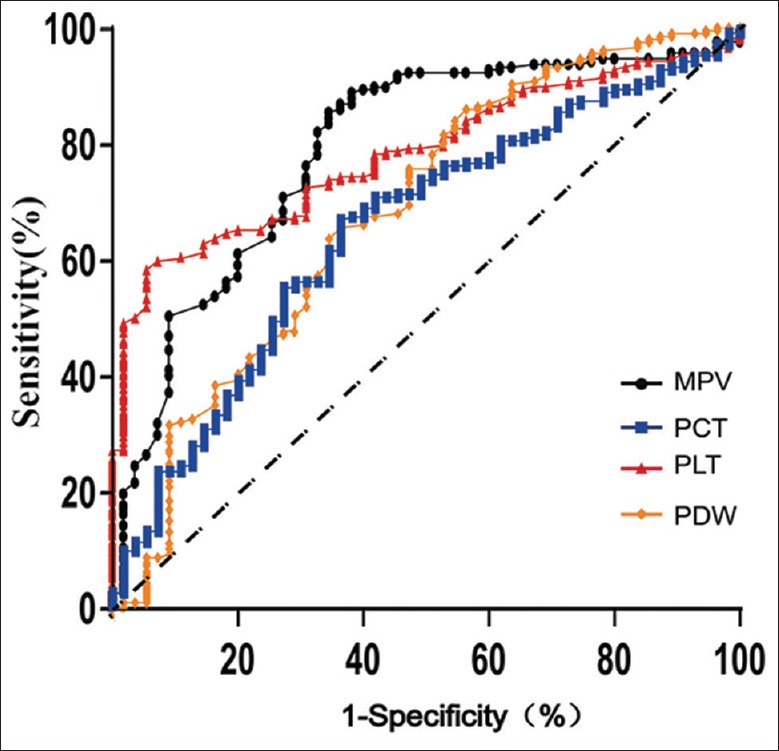

The ROCs of four PLT indices on predicting mortality were shown in Figure 1 and Table 3. PLT and MPV obtained the largest areas under ROCs of 0.78 and 0.79, respectively. PCT and PDW obtained lesser areas under ROCs of 0.66 and 0.68, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity for PLT were 60.1% and 91.2%, both of which were slightly higher than those of MPV (58.2% and 90.2%). However, MPV has the highest diagnostic accuracy (83.5%) among the four PLT indices. PLT count and MPV also obtained better positive likelihood ratio (6.9 and 6.0) and the negative ratio (0.4 and 0.5) compared to those of PCT and PDW.

Figure 1.

ROC for platelet indices in predicting mortality. The area under ROC (AUC) for MPV, PCT, PLT and PDW were 0.78, 0.66, 0.79, 0.68. The AUC for the combined index of MPV and PLT was 0.80. ROC: Receiver operating curve; AUC: Area under the ROC curve; MPV: Mean platelet volume; PCT: Plateletcrit; PLT: Platelet; PDW: Platelet distribution width percentage.

Table 3.

Diagnostic parameters of ROCs by platelet indices on predicting mortality

| Platelet indices | AUC | Optimal cutoff point | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Diagnostic accuracy, % | PLR | NLR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLT | 0.78 | 169 | 60.1 | 91.2 | 66.9 | 6.9 | 0.4 |

| PCT | 0.66 | 0.18 | 67.5 | 63.2 | 66.5 | 1.8 | 0.5 |

| MPV | 0.79 | 15.1 | 58.2 | 90.2 | 83.5 | 6.0 | 0.5 |

| PDW | 0.68 | 16.1 | 60.0 | 67.5 | 65.9 | 1.8 | 0.6 |

ROC: Receiver operating curve; AUC: Area under the ROC curve; PLR: Positive likelihood ratio; NLR: Negative likelihood ratio; PLT: Platelet; PCT: Plateletcrit; MPV: Mean platelet volume; PDW: Platelet distribution width percentage.

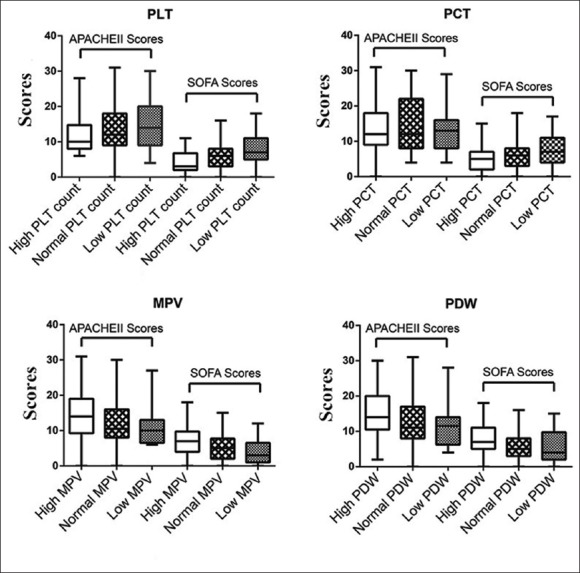

The relationship between platelet indices and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scores and sequential organ failure assessment scores

All the PLT indices were divided into tertiles of normal range, higher than upper limit, lower than lower limit. APACHE II and SOFA scores in each tertile were presented in Figure 2. For PLT, the M and IQR of the APACHE II and SOFA scores in the “low PLT” tertile were 14.0 (9.0–20.0) and 7.0 (5.0–10.5), respectively. Correspondingly, the APACHE II and SOFA scores in the “normal PLT” tertile were 12.0 (9.0–18.0; P = 0.170) and 6.0 (3.0–8.0; P = 0.002), respectively. For PCT, the APACHE II and SOFA scores in the “low PCT” tertile were 13.0 (8.0–16.0) and 7.0 (4.0–11.0), respectively, and were not significantly different to those in the “normal PCT” tertile, which were 12.0 (8.0–22.5; P = 0.531) and 6.0 (3.0–8.0; P = 0.141), respectively. For MPV, the APACHE II and SOFA scores in the “high MPV” tertile were 14.0 (9.3–19.0) and 7.0 (4.0–9.8) respectively and were significantly higher than those in the “normal MPV” tertile that were 10.5 (8.0–16.0; P = 0.008) and 5.0 (2.0–7.3; P = 0.001), respectively. For PDW, the APACHE II and SOFA scores in the “high PDW” were 14.0 (10.5–20.0) and 7.0 (5.0–11.0) respectively and were higher than that in the “normal PDW” tertile, which were 11.0 (8.0–16.0; P = 0.002) and 5.0 (3.0–8.0; P = 0.001), respectively.

Figure 2.

APACHE II and SOFA scores in patients with normal and abnormal platelet indices. The four platelet indices of PLT, PCT, MPV, and PDW were divided into three tertiles of lower than low limit, higher than up limit and normal range. The APACHE II and SOFA scores were calculated and graphically depicted as median, interquartile range, maximum value and minimum value. APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; SOFA: Sequential organ failure assessment; PLT: Platelet; PCT: Plateletcrit; MPV: Mean platelet volume; PDW: Platelet distribution width percentage.

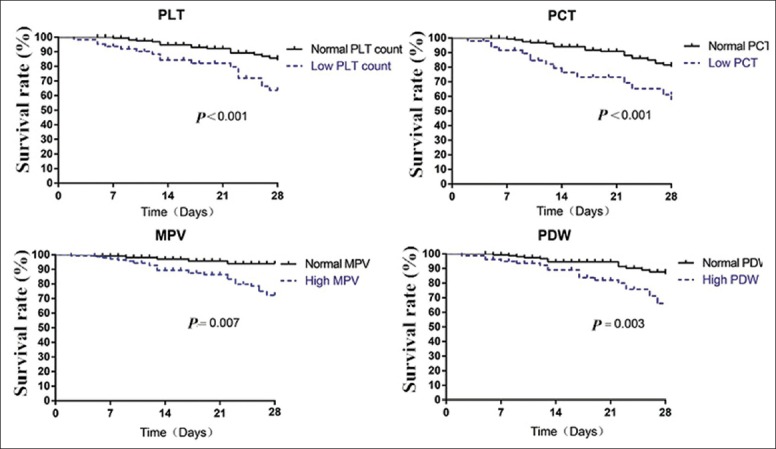

Survival curves by patients with normal and abnormal platelet indices

The 28-day survival curves for patients with normal and abnormal PLT indices were shown in Figure 3. Patients with decreased PLT and PCT values had significantly shortened length of survival than those with normal PLT and PCT values (both P < 0.001). Similarly, patients with increased MPV and PDW values had significantly shortened length of survival than those with normal range of MPV and PDW (P = 0.007 and 0.003, respectively).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with normal and abnormal platelet indices were compared and log-rank test were assessed for significance. PLT: Platelet; PCT: Plateletcrit; MPV: Mean platelet volume; PDW: Platelet distribution width percentage.

DISCUSSION

In our study, we found that patients with abnormally low PLT, abnormally high MPV value and abnormally high PDW value had higher APACHE II and SOFA scores than those with normally PLT indices, indicating that patients with abovementioned abnormally PLT indices were likely to have more severe illness. In addition, we also demonstrated that patients with reduced PLT and PCT or increased MPV and PDW had shortened length of survival as compared to patients with normal PLT indices.

Platelet indices are a group of indices that are used to measure the PLT count and PLT morphology. Under physiological conditions, the amount of PLTs in blood can be maintained in an equilibrium state by regeneration and elimination. Thus, either the PLT or their morphology remains relatively constant. Under pathophysiological conditions, any factor which could inhibit PLT regeneration, increase their activation or accelerate their death once overwhelming the capacity of self-regulation will cause changes in both PLT count and morphology and thus results in a change in PLT indices.[13] Researches have shown that activation of the coagulation system, severe infection, trauma, systemic inflammatory reaction syndrome and thrombotic diseases could all result in changes in PLT indices. Reduction in PLT has been proved to be one of the independent risk factors for ICU patients.[14,15] PCT is the arithmetic product of PLT count and PLT volume, which is positively correlated with PLT. A reduction of PLT and PCT simultaneously indicates that PLTs have been excessively consumed. MPV is the measure of PLT volume. When PLTs have been excessively consumed, bone marrow will produce a large amount of immature PLTs which have larger volume than mature ones. At that time, both newly produced PLTs with large volume and mature PLTs with small volume simultaneously present in the blood, therefore, both MPV and PDW (coefficient of PLT variation) will be increased correspondingly.[5] Thus, instead of only measuring PLT as has been done previously, to measure all of the PLT indices, will provide us a more comprehensive view of illness severity and an insight into potential etiology which has been induced changes in PLTs indices. Two previously published researches reported that in sepsis or septic shock patients, in-hospital mortality was negatively correlated with PLT and PCT values, and positively correlated with MPV and PDW values. In addition, increased MPV and PDW have been considered as predictors of poor outcomes among a number of diseases, including sleep apnea syndrome,[16] chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,[17] myocardial infarction[18] and infection.[19]

Our study found that PLT indices were also useful in determining illness severity and predicting prognosis in critically ill patients. In our univariate analysis, we found that patients who had lower PLT and PCT were more likely to die than those who had normal PLT and PCT. Similarly, patients who had higher MPV and PDW were associated with higher mortality as compared to those with normal MPV and PDW. In multivariate logistic regression model, reduced PLT count and PCT, increased MPV and PDW were still four independent risk factors for mortality even after they were adjusted for other covariates related to clinical variables. To analyze the performance of PLT indices in predicting mortality, we built the ROC for each PLT index and calculated the diagnostic parameters for all the PLT indices. In our study, PLT and MPV possessed the largest areas under ROC of 0.78 and 0.79, respectively. In addition, MPV also ranked the supreme of predictive accuracy among the four indices. Thus, MPV was inferred to be the optimal predictive indicator. However, in another study, which reported that all the AUCs of PLT indices were lower than 0.65 when predicting mortality, indicating a poor operating performance.[5] One possible explanation for the poor performance of ROCs may be the inclusion criteria of patients used in that study was not specified. For example, the patients who had received PLT infusion were not excluded in that study. Additionally, patients came from various regions could have variations in PLT indices.[19] In the following survival analysis, we found that patients with abnormally low PLT, abnormally low PCT value, abnormally high MPV value or abnormally high PDW value had significantly shortened length of survival than those with normal PLT indices.

Our studies also have several limitations. First, due to more specified inclusion and exclusion criteria in this study, a number of patients were precluded and inevitably resulted in limited sample size. Second, we did not conduct stratified analysis on whether there was a difference when PLT indices were applied as a predictor in patients with different disease. This was because patients in our ICU often bear several etiologies, making it difficult to discriminate the effect of a certain disease on PLT indices. Third, this is a retrospective study that inevitably had a risk to introduce selective bias. Forth, although we found that several abnormal PLT indices were associated with higher risk of death and more severe illness, the causal relationship cannot be verified in the present study. Our study also has several strong points. First, to our knowledge, previous studies were mainly focused on the relationship between PLT indices and patients prognosis. However, in this study, we found that a linkage between abnormal PLT indices and illness severity. Second, we selected patients by a more specified criteria, which could partly eliminate the effects of cofounders.

With the progress in health care examination, increasing novel indices have been applied in diagnosis and prediction of clinical outcomes, such as red blood cell β-subunit,[20] soluble CD14 subtype[21] and presepsin.[22] However, these novel diagnostic indices are expensive and ineffective in timeliness. PLT indices can be simply and rapidly measured from routine blood examination that is inexpensive and repeatable, providing a simple and convenient stratification tool for illness severity. If a patient presents reduced PLT count and PCT indices or elevated MPV and PDW indices at admission, more intensive supervision and aggressive treatment may be needed to prevent exacerbation.

In conclusion, PLT indices are valuable indicators of illness severity and effective predictors of clinical outcomes. Abnormally low PLT, high MPV value, and high PDW value are associated with more severe illness. In addition, patients have higher risk of death when they present reduced PLT count and PCT or increased MPV and PDW as compared to patient with normal PLT indices.

Footnotes

Edited by: Xin Chen

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gardiner EE, Andrews RK. Structure and function of platelet receptors initiating blood clotting. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;844:263–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2095-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golebiewska EM, Poole AW. Platelet secretion: From haemostasis to wound healing and beyond. Blood Rev. 2015;29:153–62. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Mikhailidis DP, Kitas GD. Mean platelet volume: A link between thrombosis and inflammation? Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:47–58. doi: 10.2174/138161211795049804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guclu E, Durmaz Y, Karabay O. Effect of severe sepsis on platelet count and their indices. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13:333–8. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v13i2.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Z, Xu X, Ni H, Deng H. Platelet indices are novel predictors of hospital mortality in intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2014;29:885.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sezgi C, Taylan M, Kaya H, Selimoglu Sen H, Abakay O, Demir M, et al. Alterations in platelet count and mean platelet volume as predictors of patient outcome in the respiratory intensive care unit. Clin Respir J. 2014 doi: 10.1111/crj.12151. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catal F, Tayman C, Tonbul A, Akça H, Kara S, Tatli MM, et al. Mean platelet volume (MPV) may simply predict the severity of sepsis in preterm infants. Clin Lab. 2014;60:1193–200. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2013.130501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdel-Razik A, Eldars W, Rizk E. Platelet indices and inflammatory markers as diagnostic predictors for ascitic fluid infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:1342–7. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rechcinski T, Jasinska A, Forys J, Krzeminska-Pakula M, Wierzbowska-Drabik K, Plewka M, et al. Prognostic value of platelet indices after acute myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiol J. 2013;20:491–8. doi: 10.5603/CJ.2013.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW., Jr A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115:92–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fluss R, Faraggi D, Reiser B. Estimation of the Youden Index and its associated cutoff point. Biom J. 2005;47:458–72. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200410135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gadó K, Domján G. Thrombocytopenia. Orv Hetil. 2014;155:291–303. doi: 10.1556/OH.2014.29822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han L, Liu X, Li H, Zou J, Yang Z, Han J, et al. Blood coagulation parameters and platelet indices: Changes in normal and preeclamptic pregnancies and predictive values for preeclampsia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghoshal K, Bhattacharyya M. Overview of platelet physiology: Its hemostatic and nonhemostatic role in disease pathogenesis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:781857. doi: 10.1155/2014/781857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nena E, Papanas N, Steiropoulos P, Zikidou P, Zarogoulidis P, Pita E, et al. Mean Platelet Volume and Platelet Distribution Width in non-diabetic subjects with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: New indices of severity? Platelets. 2012;23:447–54. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2011.632031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steiropoulos P, Papanas N, Nena E, Xanthoudaki M, Goula T, Froudarakis M, et al. Mean platelet volume and platelet distribution width in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The role of comorbidities. Angiology. 2013;64:535–9. doi: 10.1177/0003319712461436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirbas Ö, Kurmus Ö, Köseoglu C, Duran Karaduman B, Saatçi Yasar A, Alemdar R, et al. Association between admission mean platelet volume and ST segment resolution after thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2014;14:728–32. doi: 10.5152/akd.2014.5078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Sweedan SA, Alhaj M. The effect of low altitude on blood count parameters. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2012;5:158–61. doi: 10.5144/1658-3876.2012.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoo H, Ku SK, Kim SW, Bae JS. Early diagnosis of sepsis using serum hemoglobin subunit Beta. Inflammation. 2015;38:394–9. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-0043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kweon OJ, Choi JH, Park SK, Park AJ. Usefulness of presepsin (sCD14 subtype) measurements as a new marker for the diagnosis and prediction of disease severity of sepsis in the Korean population. J Crit Care. 2014;29:965–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou Q, Wen W, Zhang XC. Presepsin as a novel sepsis biomarker. World J Emerg Med. 2014;5:16–9. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]