ABSTRACT

This study explored fathers’ perceptions about breastfeeding infants. A qualitative exploratory study design was used. Study setting was urban and semiurban areas of Karachi, Pakistan. In-depth interviews were conducted with 12 fathers. The following themes emerged from the data collected: knowledge and awareness and enabling and impeding factors. Most fathers seemed eager to get involved and assist their partners in proper breastfeeding practices because they believed that doing so is in accordance with their faith. Fathers felt that adequate support from their family members and employers could enable them to encourage their partners to initiate and maintain exclusive and optimum breastfeeding practices. Exploring fathers’ perception regarding breastfeeding in the context of Pakistan is still a new field of study.

Keywords: father’s role, perception of fathers, breastfeeding practices, developing countries, fathers’ perspectives

Breastfeeding rates in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India are as low as 24%–26% in the first hour following birth (Ali, Ali, Imam, Ayub, & Billoo, 2011; Gupta, Arora, & Bhatt, 2006; Lawn, Osrin, Adler, & Cousens, 2008; Shamim, Jamalvi, & Naz, 2006). On the other hand, countries such as Sri Lanka that have committed to promote breastfeeding practices have been able to decrease their infant mortality rates. One reason for the high infant mortality and morbidity rates in Pakistan may be the fact that 84% of females do not follow exclusive breastfeeding practices (Gupta et al., 2006; Hanif, 2011; Hwang, Chung, Kang, & Suh, 2006). Although the breastfeeding initiation rate in Pakistan is about 95%, the continuity and sustainability of exclusive breastfeeding is still not very well practiced (Chen, 2011; Morisky et al., 2002; Premani, Kurji, & Mithani, 2011).

Although the breastfeeding initiation rate in Pakistan is about 95%, the continuity and sustainability of exclusive breastfeeding is still not very well practiced.

Breastfeeding is a time-intensive job, and women may require various types of support for initiation and continuation of optimum breastfeeding practices (Ball & Wright, 1999; Earle, 2002; Narayan, Natarajan, & Bawa, 2005). Essentially, at the time of breastfeeding, a woman needs to be listened to. The most critical support system is the baby’s father. Literature review also endorses that among the various supports, a “father’s support” for breastfeeding is significant to promote exclusive and optimum breastfeeding practices (Bar-Yam & Darby, 1997; Kirkland & Fein, 2003; Li, Darling, Maurice, Barker, & Grummer-Strawn, 2005; Li, Fridinger, & Grummer-Strawn, 2002; Morisky et al., 2002; Ny, Plantin, Dejin-Karlsson, & Dykes, 2008; Sikorski, Renfrew, Pindoria, & Wade, 2003; Sullivan, Leathers, & Kelley, 2004).

Authors also affirmed that fathers play a pivotal role because the breastfeeding decision is a multifaceted and complex phenomenon (Bar-Yam & Darby, 1997; International Lactation Consultant Association, 2007; Ny et al., 2008). Those mothers who receive support from their spouses usually opt for exclusive and optimum breastfeeding for their infants, and the chances of continuing this practice are higher (Flacking, Dykes, & Ewald, 2010; Ny et al., 2008; Rempel & Rempel, 2011). Many studies have also revealed that support from fathers is greatly appreciated by mothers (Bar-Yam & Darby, 1997; Kirkland & Fein, 2003; McInnes & Chambers, 2008; McLaughlin & Marascuilo, 1990; Ny et al., 2008; Quinn et al., 2001; Pisacane, Continisio, Aldinucci, D’Amora, & Continisio, 2005; Taveras et al., 2004).

RATIONALE AND AIM

However, no published data were found on the phenomenon of paternal support for breastfeeding in the Pakistani context.

Breastfeeding practices are declining in Pakistan, despite the fact that breastmilk is the ideal food for infants (Morisky et al., 2002). This descriptive exploratory study explored the knowledge, beliefs, and practices of fathers in urban and semiurban settings in Karachi, Pakistan. How fathers perceive their role in promoting breastfeeding and the barriers regarding infant feeding decisions were also explored.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Father’s Role in Breastfeeding

Father’s support has been identified as one of the strongest predictors of exclusive and optimum breastfeeding. Studies (Horton, 2005; Mitchell-Box & Braun, 2012; Scott, Landers, Hughes, & Binns, 2001) have affirmed that fathers play a pivotal role in supporting breastfeeding. Littman, Medendorp, and Goldfarb (1994) considered father’s support important in assisting mothers to initiate and continue breastfeeding. Various studies conducted in United States cite father’s support as key in initiating and maintaining breastfeeding (Ekström, Widström, & Nissen, 2003; Li et al., 2005). A study conducted to explore the declining prevalence of breastfeeding revealed that the infant feeding decision is not an individual’s decision but is multifaceted. Another study by Pisacane et al. (2005) highlighted the father’s involvement and preparedness as an essential predicator of infant feeding and further elaborated that those mothers who received support from their child’s father (intervention group) had a higher exclusive breastfeeding prevalence rate of 25%, whereas that rate was 15% for the mothers in the control group (no father’s support). Moreover, 12-month-old children of mothers in intervention group had 19% rate of successful breastfeeding, whereas it was 11% for the mothers in control group. Other studies (Flacking et al., 2010; Jordan & Wall, 1993; Lalive & Zweimüller, 2005; Sullivan et al., 2004) have indicated similar results, that is, the stronger the father’s support, the longer the duration of exclusive and optimum breastfeeding. They also reported that when fathers were supportive toward continuing and maintaining breastfeeding, mother’s rate of absenteeism from work was lower, retention rates were higher, stress on male partners was lesser, and expenses related to infant health issues were lower.

Fathers’ support is not the only factor related to breastfeeding success (Flacking et al., 2010; Gill, 2001; Kinanee & Ezekiel-Hart, 2009). A father has multiple roles, and it is not always possible for fathers to support their partners in exclusive and optimum breastfeeding practices (Arora, McJunkin, Wehrer, & Kuhn, 2000). In addition, not all fathers consider breastfeeding to be really beneficial for their infants, which is evident in one of the studies, in which 60% of the fathers reported breastfeeding as bad. In addition, 50% of these fathers mentioned that it made the breasts look ugly, whereas 80% of them reported that it interfered with maintaining a sexual relationship (Littman et al., 1994).

In short, fathers play an important role in the infant feeding decisions; however, they require prior knowledge to provide optimum support to their spouses (Flacking et al., 2010; Lalive & Zweimüller, 2005; Shirima, Gebre-Medhin, & Greiner, 2001).

METHODOLOGY

Qualitative method is used in this study. This design facilitated the paternal emic perspective, allowing the researcher to explore the inside world of the fathers’ thoughts and beliefs regarding the enabling and impeding factors of breastfeeding practices without making any judgments (Cresswell, 2007). The constructivist approach is the philosophical underpinning for this exploratory qualitative design (Boyce & Neale, 2006; Brinks & Wood, 1998; McLaughlin & Marascuilo, 1990; Polit & Beck, 2008).

Setting

A maternity home in Karachi, Pakistan, was selected as the urban study setting. This maternity home is situated in the locality of people in the lower to middle socioeconomic strata. Rehri Goth, an older than-300-year-old village situated in District Malir, Bin Qasim Town, on the outskirts of Karachi, Pakistan (Aga Khan University, n.d.), was selected as the semiurban setting. Because many couples visit the maternity home for outpatient consultations, recruitment of fathers in this setting was conducted while they waited for their wives, whereas the fathers from Rehri Goth were recruited during the community visit.

Sampling Technique and Sample Size

Twelve audiotaped interviews were conducted with 6 fathers from the urban area and 6 from the semiurban area. Purposive sampling was done with participants based on the following inclusion criteria:

-

•

Healthy fathers

-

•

Parity of partner: two to four

-

•

Couples with term single healthy infants

-

•

Previously breastfed at least one child

-

•

Couples who are not using hormonal contraceptives (pills)

-

•

Speak Urdu

-

•

Birth weight more than 2.5 kg

Data Collection Procedure

Permission for conducting interviews was obtained from the head of the department of the maternity home. Informed consent was sought from the fathers for in-depth interviews. The participants consented to be the part of the study.

Interview Guide

A semi-structured interview guide was developed, which contained open-ended and broad questions based on literature review. It was developed in English and then translated into Urdu while considering cultural equivalences, congruent values, and careful use of colloquialism. Pilot testing of in-depth interviews was carried out on those who consented and fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data Analysis

Analysis of the qualitative research commenced with data collection. Thematic analysis was done through six steps of the iterative process (LoBiondo-Wood & Haber, 2006; Polit & Beck, 2008). Data were analyzed and managed simultaneously by sketching ideas, taking field notes, summarizing field notes, identifying codes, reducing codes into themes, and finally, developing categories.

Ethical Considerations

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Aga Khan University Ethical Review Committee. In addition, written consent was taken from the participants. The consent form was developed in English and translated into Urdu. Voluntary participation was encouraged, and the participants were assured that their withdrawal from the study would not be penalized. Anonymity and confidentially were maintained.

RESULTS

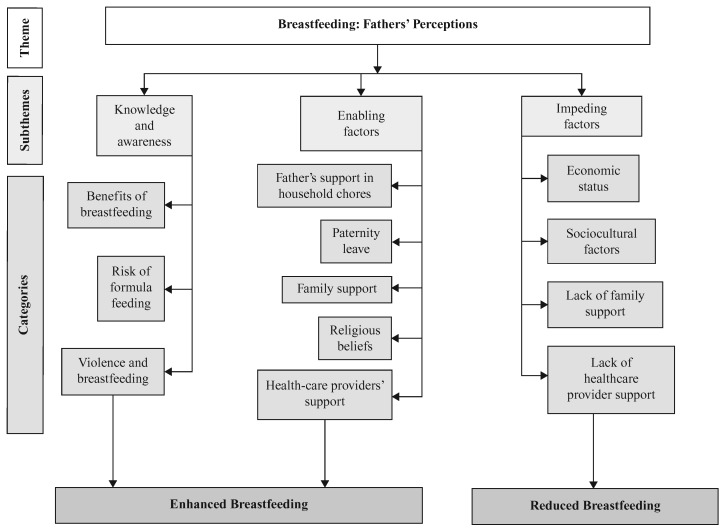

Fathers shared their perspectives about initiating and maintaining breastfeeding. The themes (Figure 1) of knowledge and awareness and enabling and impeding factors emerged from the data analysis through the iterative process (Flacking et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

Themes, categories, and subcategories of the results.

Participants’ Sociodemographic

All six participants (fathers) from the urban area were educated, whereas only one out of the six participants (fathers) from the semiurban area was educated. All participants from the semiurban area were living in extended families, whereas only a few of the participants from the urban area were living in extended families. Moreover, in the urban sample, the fathers were older, as compared to those in the semiurban setting, as represented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Fathers From the Urban and Semiurban Areas.

| Urban Fathers | Semiurban Fathers | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N = 6 | N = 6 |

| Age of participants (years) | ||

| 20–30 | 0 | 3 |

| 30–40 | 5 | 3 |

| 40–50 | 1 | 0 |

| Education of the participants | ||

| Uneducated | 0 | 3 |

| Primary/Secondary level | 1 | 2 |

| Intermediate | 0 | 1 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 4 | 0 |

| Master’s degree | 1 | 0 |

| Number of children | ||

| 1–2 | 2 | 1 |

| 3–4 | 4 | 5 |

| Type of family | ||

| Nuclear | 2 | 0 |

| Extended | 4 | 6 |

Breastfeeding: Fathers’ Perceptions

Knowledge and Awareness.

Data demonstrated that most fathers (n = 10) had knowledge and awareness of the importance of breastfeeding. The subcategories that emerged from the themes appreciating the advantages of breastfeeding were benefits of breastfeeding, risk of formula feeding, and fathers’ awareness of their role of supporting their infant’s mother while they breastfeed. These are discussed in the following text.

Advantages of breastfeeding.

Ten out of 12 fathers considered mother’s milk as complete nutrition for the first 6 months of an infant’s life, which should be continued until the age of 2 years. The reasons mentioned were that breastmilk increases the child’s immunity and provides strength to fight diseases. One of the participants even viewed breastmilk as a “wonderful gift of nature.” One of the fathers from the semiurban area said, “A mother’s milk is nutritious [shakti wala hay], particularly until 6 months of age.”

Disadvantages of formula feeding.

Fathers from the urban setting were aware of the risks of breastmilk substitutes and asserted that they had many disadvantages, including causing diarrhea in infants. Three out of the 12 fathers even reported that a baby should be fed breastmilk substitutes only when situations are beyond control (majboori). Another father mentioned the disadvantages of breastmilk substitutes as follows:

Formula milk is very dangerous for babies’ health. The child gets ill and does not put on weight [Bacha sookh jata hay aur wazan bhi nahi burtha hay]. It is not healthy for mothers also she may get different types of cancers.

However, two fathers from the semiurban areas stressed that breastmilk substitutes are more healthy and convenient. As one of them expressed,

I encourage my wife to breastfeed because I am poor although she insists on bringing formula milk . . . The cost is very high . . . babies who are bottle-feeding are more healthy and chubby.

Violence and breastfeeding.

While expressing the benefits of breastmilk and the risks of nonbreastfeeding, an interesting perspective was reported by two of the fathers from the semiurban area. It revealed a reluctance to engage in domestic violence toward their wives during the breastfeeding period. As one of them said,

I always support my wife for breastfeeding . . . I never hurt her. Even when I want to hit her I do not because I know she is very weak . . .

Enabling Factors for Fathers.

According to the fathers’ narration, various factors supported, promoted, and protected breastfeeding. Multiple factors were perceived as significant enabling factors by 9 out of 12 fathers, such as father’s support, resistance to violence, paternity leave, family support, health-care provider’s support, and religious beliefs.

Father’s support in household chores.

Nine out of 12 fathers reported that they considered their role to be important and crucial for their wives to initiate and maintain breastfeeding. Interestingly, all the fathers, from both urban and semiurban areas (n = 12), explicated that they cannot do anything directly for breastfeeding; however, they can perform various other tasks to assist their partners, such as taking care of household chores; looking after the older children; taking care of their wife’s diet, rest, and sleep; and participating in the care of the newborn baby. One of the participants from the semiurban setting reported,

I am very supportive of my wife. When my wife wakes up at night to feed, I also wake up and sit with her so that she does not feel alone and when she complains of lack of milk supply, I bring brown sugar [mitha gur], which helps in increasing the milk supply.

Three participants reported that although fathers could help support their wives in performing household chores, they would be unable to fulfill this responsibility, because of societal pressures and their own work routine. However, one of the father’s views was in complete contradiction of the ones mentioned earlier. He labeled breastfeeding as the mother’s responsibility entirely, with the father having nothing to do with it. Sharing his opinion, he said,

Fathers cannot play any significant role in the promotion of breastfeeding as it is entirely the mother’s responsibility. Even at night if the baby cries, the mother is responsible to wake up and take care of the baby. That is why God has put paradise under a mother’s feet [Ma Kay kadmo may jannat hay] . . .

Paternity leave.

Some of the fathers endorsed that paternity leave could help support them in their involvement in maternal and child care. Two of the fathers, one from the urban and the other from the semiurban area, acknowledged their employer’s support, but 10 out of the 12 fathers stated that they were not granted paternity leave in their organization. Yet they all recognized it as a supporting factor. For instance, the participant from the urban area explained,“ . . . Paternity leaves facilitated my wife in exclusive breastfeeding and I was able to take care of the older children.”

On the contrary, one of the participants from the urban area related that his employer did not encourage paternity leave because he viewed it as part of western culture and thought it was not necessary for fathers because family support is available at home. He mentioned,

I am well aware about a father’s role in breastfeeding but . . . my boss says its westernized culture, it’s the mother’s responsibility to feed the child . . . they do not want to disturb their work, as they had gone through this phase.

Family support.

Family support, particularly from mothers-in-law and elder sisters, was beneficial in the immediate postpartum period. Overall, fathers from the semiurban area were living in extended families and felt that obtaining help from family members was one of the driving forces for them. Eleven out of the 12 fathers considered family support a major supporting factor. As one father from the urban area shared, “Our social system is a cushion. My mother-in-law came and . . . stayed with us. It was a big help . . . ”

Conversely, another father from the urban area expressed that his mother’s attitude toward breastfeeding was not very supportive. He stated,

My mother insists on initiating formula feed for my babies as, according to her perception, formula-fed babies are chubbier . . . I think she herself was not able to feed us, therefore she was jealous of her daughter-in-law . . .

Health-care provider support.

Most study participants (n = 7) from urban as well as semiurban areas said health-care providers were very supportive in encouraging breastfeeding and solving initial lactation problems. They never approached the fathers directly, however, and spoke exclusively to the mothers regarding breastfeeding issues. As one of the fathers reported, “Doctors and nurses encourage breastfeeding a lot though there were no formal classes to prepare my wife.”

Another participant said, “Nurses and doctors also encourage mothers to breastfeed via creating awareness about benefits of breastfeeding.”

Religious beliefs.

Religious beliefs were a major enabling factor in initiating breastfeeding for most participants (n = 9). For instance, one of the participants from the urban setting reported, “Quran and Hadiths [sayings of the Holy Prophet Mohammad] have also recommended that mothers shall feed their child.”

Congruent with this religious belief, another participant from the semiurban setting said, “ . . . because I want to follow the guidance of the Quran . . . if God has given diet for the child, how can we human beings disrespect and devalue the child’s right [Bachay ka haq hay]?”

Impeding Factors for Fathers.

The study findings indicated that fathers experienced many barriers such as socioeconomic and cultural factors and lack of family and health-care provider’s support in promoting, initiating, and maintaining breastfeeding for their infants.

The study findings indicated that fathers experienced many barriers such as socioeconomic and cultural factors and lack of family and health-care provider’s support in promoting, initiating, and maintaining breastfeeding for their infants.

Economic status.

Some fathers perceived that their economic status was one of the impeding factors in initiating and maintaining breastfeeding. For example, two fathers from the semiurban and one from the urban area believed that because of their state of destitution, their wives could not eat a balanced diet, therefore compromising the quality and quantity of mother’s milk. One of the fathers from the urban area said, “Due to poverty [Garibi], my wife cannot eat meat, fruits, and fish; therefore, her quality of milk is not good for my baby.”

Sociocultural factors.

The study further determined that the sociocultural factor of male dominance is also perceived as impacting breastfeeding. Three out of 12 participants, 2 of them from the semiurban and 1 from the urban area, asserted that breastfeeding was a role designated to females only; men had nothing to do with it because they were very busy earning money.

One of the fathers said, “When my child awakes in the night, I get frustrated and angry with both mother and child. Men are supposed to be bread earners. Once they come home, everything should be settled.”

In contrast, one of the fathers from the urban setting had a different view. He mentioned, “Wife is not a factory of child production. Religion, Quran, and Hadiths also suggest respecting the wife but as men are more dominating, divorce rates are increasing.”

Lack of family support.

Interestingly, the fathers perceived family members as both enabling and hindering factors in the promotion of breastfeeding. Two fathers from the urban setting found family as a barrier, particularly mothers-in-law and sisters-in-law. For instance, one of them reported, “My wife had an increased work load [due to joint family] so she could not breastfeed our baby. Thus, we were helpless and initiated bottle feeding.”

Likewise, another one said, “My family [elder sister] did not support our breastfeeding decision, and my wife was pressured to keep the baby on both [breastfeeding and bottle feeding].”

Lack of health-care provider support.

Health-care provider support was also indicated as an enabling as well as an impeding factor. Many fathers (n = 9) verbalized a feeling of being left out. They further mentioned that antenatal classes are only conducted for mothers, and fathers are never invited for fatherhood classes. Most of these participants expressed the view that health-care providers did not prepare fathers to support their wives during breastfeeding. One of them complained,

When we came for the checkup after delivery and my wife complained of lack of milk supply, the doctor immediately started my baby on formula [upar ka dood shuru kurdya] . . . slowly, gradually the baby was switched to partial breastfeeding.

DISCUSSION

The study results revealed that breastfeeding was not effortless and that multifaceted interventions were required to initiate and maintain optimal breastfeeding. The fathers verbalized various enabling and impeding factors for exclusive breastfeeding, as shown in Figure 1. It was interesting to note that most fathers from the urban as well as from the semiurban areas verbalized the significance of breastmilk for infants and the risks of breastmilk substitutes, yet their spouses were unable to initiate breastfeeding immediately after birth because of their strong beliefs of azan (call for prayers), prelacteal feedings, and perception of colostrum being dirty and poisonous. Previous studies in Nepal, India, and Pakistan also have affirmed this finding (Fikree, Ali, Durocher, & Rahbar, 2008; Khadduri et al., 2008; Laroia & Sharma, 2006; Moran & Gilad, 2007). A study done in the United Kingdom also concluded that breastfeeding was delayed because of strong cultural values and beliefs (Ingram, Johnson, & Hamid, 2003). Strikingly, despite the fathers’ awareness of the benefits of breastfeeding, they, for the most part, reported that their infants were on partial rather than exclusive breastfeeding.

The study findings also revealed an unusual benefit of breastfeeding, which was the couples’ improved relationship. Most fathers felt that breastfeeding increased their bonding with their wives. Similar findings were also reported by a study conducted in Turkey, in which fathers reported feeling closer to their partner after the birth of their infants and felt that their workload sharing had increased (O’Brien & Shemilt, 2003).

On the contrary, differences were also discovered in the findings of this and some other studies pertaining to the fathers’ perspectives about intimacy between couples because of breastfeeding. Rempel and Rempel (2011) stated that some fathers felt lack of intimacy in their relationship as their partners were busy breastfeeding and taking care of their babies. Byrd, Hyde, DeLamater, and Plant (1998) also affirmed that fathers felt left out and believed that their intimacy with their partners was adversely affected by breastfeeding.

Another interesting finding was determined through this study. Two fathers from the semiurban area reported a very different perspective on the kind of support they provided to their wives. One of them noted that he did not verbally abuse his wife to support her because he feared that she might go away. Similarly, the other participant shared that he supported his wife by not hitting her because he did not have the money to pay for the doctor’s visit in case of an injury. Both of these perspectives were astonishing; in reality, the fathers were protecting their own interests by ensuring that their wives stayed at home, not protecting their wives from getting hurt. However, literature reveals that women who are in abusive relationships have difficulty breastfeeding. For instance, Averbuch (2009), Bowman (2007), and Fikree, Razzak, and Durocher (2005), reported that when women in such relationships are breastfeeding, domestic violence increases, which may cause insufficient milk syndrome.

The study findings revealed various measures through which fathers could support their spouses during breastfeeding. These were consistent among the fathers from both urban and semiurban settings. All the fathers recognized that while their wives breastfed, they could assist them by changing infants diapers and burping, swaddling, and holding them (Ny et al., 2008; Pisacane et al., 2005; Rempel & Rempel, 2011; Wolfberg et al., 2004). Literature (Kirkland & Fein, 2003; Littler, 1997; McLaughlin & Marascuilo, 1990) also suggests that fathers are instrumental in performing familial roles. This result was surprising for the researcher because it was assumed that fathers from the semiurban area would not take the responsibility of assisting their partners while they breastfeed.

According to a study conducted in Kuwait by Dashti, Scott, Edwards, and Al-Sughayer (2010), women valued multiple family members. Another important finding of the study validates that family support plays a pivotal role in the success of breastfeeding (Jordan & Wall, 1993; Sullivan et al., 2004).

Results from a study performed in Tanzania (Shirima et al., 2001) also highlighted that not only the father’s support but also family support were extremely significant for initiating and maintaining exclusive breastfeeding. Likewise, in Pakistan, it is expected that the female members of a family will help one another with any issues involving maternal and child health. Similarly, a study done in the United Kingdom with Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Indian mothers-in-law by Ingram et al. (2003) affirmed that elderly female members played a significant role for mothers during breastfeeding.

Religious beliefs were considered as one of the significant factors among both urban and semiurban fathers in promoting breastfeeding. All of the study participants agreed that they encouraged their wives to initiate and maintain breastfeeding because it is advised in their religion; hence, it played a motivational role. Similar observations are noted in studies conducted in Pakistan, Nepal, and India (Laroia & Sharma, 2006; Moran & Giland, 2007). Religious beliefs can act as a major driving force for breastfeeding.

The results further indicated that all of the fathers in this study recognized the importance of husband’s support in breastfeeding their infant. Yet, because of lack of employers’ support and their role as breadwinners for their families, they were unable to fully support their wives while they breastfed. Most fathers from both the urban and semiurban areas viewed paternity leaves as an enabling factor, as confirmed by the literature. However, only 2 out of 12 fathers received it and thus actually got involved in caring for their wife and child. A few of the fathers acknowledged that health-care providers’ support facilitated the initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding (Dashti et al., 2010; Li et al., 2005). For instance, fathers from both study settings indicated that attending antenatal classes with their wives enabled them to maintain breastfeeding for their child as a couple. The literature also shows that breastfeeding initiation rates were higher (74%) when fathers attended a 2-hours prenatal intervention, whereas it was 41% for the fathers in the control group (Li et al., 2002). This study revealed the lack of health-care provider support as a barrier to breastfeeding. Most fathers (n = 10) were of the view that they were never involved in maternal and child health care. Although they accompanied their wives for antenatal checkups, they just sat in the waiting area and were never approached by any nurse or doctor during their wife’s or child’s checkups. A few of the fathers reported their intense dissatisfaction with the quality of health care received by their wives and suggested that health-care providers also needed training and competency for improving communication with husbands. This observation is consistent with those mentioned by Furber and Thomson (2007).

IMPLICATIONS

The findings of this study will help various stakeholders:

-

1

Fathers: sharing opportunity to reflect on their roles and experiences related to breastfeeding

-

2

Policy makers: The enabling and impeding factors highlighted by the study may provide directions for decision making and policy-level changes related to breastfeeding practices. Based on the study findings, an employer-allocated paternity leave of around 4–6 weeks would facilitate a reversal in declining breastfeeding rates.

-

3

Health-care professionals: To the best of our knowledge and based on the literature search for related studies in Pakistan, no national qualitative data pertaining to the topic under discussion is available. Thus, it is expected that this study will add new knowledge to the area of study, which may have a positive impact on maternal and child health outcomes.

Breastfeeding has always been considered a women’s issue, whereas fathers are usually considered bread winners. Being lactation consultants, this study helped us in clarifying our own biases regarding fathers’ perceptions of breastfeeding in urban and semiurban communities. The lessons learned will be shared with other lactation consultants and health professionals.

RECOMMENDATIONS

-

•

The study findings also revealed a gradual change in the fathers’ perceptions about breastfeeding support in the semiurban and urban areas. Hence, impact of father’s education on infant feeding choice and the support provided can further help to develop strategies to improve health outcomes.

-

•

A few participants also shared that the quality of mother’s milk was compromised because of poverty, which in turn led to cessation of breastfeeding. Thus, more studies are needed to explore the impact of socioeconomic status on quality of breastmilk in developing countries and its implications for breastfeeding.

-

•

Pakistan has a male-dominant culture where females are suppressed and gender discrimination is very common. Hence, more research is required to understand the impact of gender discrimination on exclusive and optimum breastfeeding practices.

CONCLUSION

Fathers are motivated by maternal and child well-being. This study found that if fathers’ perspectives on breastfeeding support were taken into consideration, improvements could be seen in the declining rates of breastfeeding.

Most fathers seemed eager to get involved and assist their partners in proper breastfeeding practices because they believed that doing so was in accordance with their faith. It was further determined that adequate support from family members, health-care professionals, and employers can enable fathers to encourage and facilitate their partners to initiate and maintain exclusive and optimum breastfeeding. Along with enabling factors, fathers also identified some obstacles to breastfeeding. Many of them felt that the sociocultural environment, lack of family support, and scarcity of health-care providers served as challenges to proper and extended breastfeeding practices. This is a new field of study in Pakistan. Further research is needed before more substantial evidence can be obtained.

Because this study has identified multifaceted factors, as elucidated by fathers, a set of contextualized strategies can be planned to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding. Further research is needed before more substantial evidence can be obtained.

Biographies

YASMIN MITHANI, RM, RN, BScN, IBCLC, MSc, is a senior instructor/Year 1 and 2 coordinator at the Aga Khan University School of Nursing and Midwifery.

ZAHRA SHAHEEN PREMANI, RN, BScN, IBCLC, MSc, is chief operating officer at Catco Kids, Inc., in Karachi, Pakistan.

ZOHRA KURJI, RN, BScN, IBCLC, MSc, is a senior instructor/curriculum chair at the Aga Khan University School of Nursing and Midwifery.

SHEHNAZ RASHID, RN, BScN, IBCLC, is a research coordinator for the Sharjah Baby-Friendly Campaign, Government of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates.

REFERENCES

- Aga Khan University (n.d.). Urban health program, community health sciences. Aga Khan University, 318–327. Retrieved from http://www.aku.edu/chs/chsuhpfield.shtml#rehri

- Ali S., Ali S. F., Imam A. M., Ayub S., Billoo A. G. (2011). Perception and practices of breastfeeding of infants 0-6 months in an urban and a semi-urban community in Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 61(1), 99–104. Retrieved from http://www.scopus.com/record/display.url?eid=2-s2.0-78651245488&origin=inward&txGid=CC5331E46F9621055437A624B13EDB6A.I0QkgbIjGqqLQ4Nw7dqZ4A%3a2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S., McJunkin C., Wehrer J., Kuhn P. (2000). Major factors influencing breastfeeding rates: Mother’s perception of father’s attitude and milk supply. Pediatrics, 106(5), E67 Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/106/5/e67.full.ht [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averbuch T. (2009). Breastfeeding mothers and violence: What nurses need to know. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 34(5), 284–289. Retrieved from http://www.nursingcenter.com/lnc/JournalArticle?Article_ID=931994&JournalID=54021&Issue_ID=931983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball T. M., Wright A. L. (1999). Health care costs of formula-feeding in the first year of life. Pediatrics, 103(4, Pt. 2), 870–876. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10103324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yam N. B., Darby L. (1997). Fathers and breastfeeding: A review of the literature. Journal of Human Lactation, 31(1), 45–50. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9233185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman K. G. (2007). When breastfeeding may be a threat to adolescent mothers. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 28(1), 89–99. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17130009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce C., Neale P. (2006). Monitoring and evaluation—2. Conducting in-depth interviews: A guide for designing and conducting in-depth interviews for evaluation input. Retrieved from http://www2.pathfinder.org/site/DocServer/m_e_tool_series_indepth_interviews.pdf?docID=6301

- Brinks J. P., Wood M. J. (Eds.). (1998). Advanced design in nursing research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd J. E., Hyde J. S., DeLamater J. D., Plant E. A. (1998). Sexuality during pregnancy and the year postpartum. Journal of Family Practice, 47(4), 305–308. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9789517 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. (2011). Breastfeeding knowledge, attitude, practice and related determinants among mother in Guangzhou, China. Retrieved from http://hub.hku.hk/handle/10722/132348

- Creswell J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design. Retrieved from http://community.csusm.edu./pluginfile.php12115/modresource/content/desi.

- Dashti M., Scott J. A., Edwards C. A., Al-Sughayer M. (2010). Determinants of breastfeeding initiation among mothers in Kuwait. International Breastfeeding Journal, 5(7), 1–9. 10.1186/1746-4358-5-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earle S. (2002). Factors affecting the initiation of breastfeeding: Implications for breastfeeding promotion. Health Promotion International, 17(3), 205–214. Retrieved from http://heapro.oxfordjournals.org/content/17/3/205.full.pdf+html?sid=5b914761-1050-4d8f-9bc0-541384a36774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekström A., Widström A. M., Nissen E. (2003). Breastfeeding support from partners and grandmothers: Perceptions of Swedish women. Birth, 30(4), 261–266. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14992157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fikree F. F., Ali T. S., Durocher J. M., Rahbar M. H. (2008). Newborn care practices in low socioeconomic settlements of Karachi, Pakistan. Social Science & Medicine, 60(5), 911–921. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15589663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fikree F. F., Razzak J. A., Durocher J. (2005). Attitudes of Pakistani men to domestic violence: A study from Karachi, Pakistan. The Journal of Men’s Health & Gender, 2(1), 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Flacking R., Dykes F., Ewald U. (2010). The influence of fathers’ socioeconomic status and paternity leave on breastfeeding duration: A population-based cohort study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 38(4), 337–343. 10.1177/1403494810362002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furber C. M., Thomson R. M. (2007). Midwives in the UK: An exploratory study of providing newborn feeding support for postpartum mothers in the hospital. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 52(2), 142–147. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S. L. (2001). The little things: Perceptions of breastfeeding support. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 30(4), 401–409. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11461024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A., Arora V., Bhatt B. (2006). The state of the world’s breastfeeding: Pakistan report card. Retrieved from http://www.worldbreastfeedingtrends.org/reportcard/Pakistan.pdf

- Hanif H. M. (2011). Trends in breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in Pakistan, 1990–2007. International Breastfeeding Journal, 6, 15 10.1186/1746-4358-6-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W. J., Chung W. J., Kang D. R., Suh M. H. (2006). Factors affecting breastfeeding rate and duration. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, 39(1), 74–80. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16613075 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J., Johnson D., Hamid N. (2003). South Asian grandmothers’ influence on breastfeeding in Bristol. Midwifery, 19(4), 318–327. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14623511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Lactation Consultant Association (2007). Position paper on breastfeeding and work. Retrieved from http://www.ilca.org/files/resources/ilca_publications/BreasfeedingandWorkPP.pdf

- Jordan P. L., Wall V. R. (1993). Supporting the father when an infant is breastfed. Journal of Human Lactation, 9(1), 31–34. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8489721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadduri R., Marsh D. R., Rasmussen B., Bari A., Nazir R., Darmstadt G. L. (2008). Household knowledge and practices of newborn and maternal health in Haripur district, Pakistan. Journal of Perinatology, 28(3), 182–187. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18059464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinanee J. B., Ezekiel-Hart J. (2009). Men as partners in maternal health: Implications for reproductive health counselling in Rivers State, Nigeria. Journal of Psychology and Counseling, 1(3), 39–44. Retrieved from http://www.academicjournals.org/article/article1379759046_Kinanee%20and%20Ezekiel-Hart.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland V. L., Fein S. B. (2003). Characterizing reasons for breastfeeding cessation throughout the first year postpartum using the construct of thriving. Journal of Human Lactation, 19(3), 278–285. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12931779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalive R., Zweimüller J. (2005). Does parental leave affect fertility and return-to-work? Evidence from a “true natural experiment” (Working Paper No. 242). Zurich, Switzerland: Institute for Empirical Research in Economics, University of Zurich; Retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/p/zur/iewwpx/242.html [Google Scholar]

- Laroia N., Sharma D. (2006). The religious and cultural bases for breastfeeding practices among the Hindus. Breastfeeding Medicine, 1(2), 94–98. Retrieved from http://www.dors.it/latte/docum/Hindus.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn J. E., Osrin D., Adler A., Cousens S. (2008). Four million neonatal deaths: Counting and attribution of cause of death. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 22(5), 410–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Darling N., Maurice E., Barker L., Grummer-Strawn L. M. (2005). Breastfeeding rates in the United States by characteristics of the child, mother, or family: The 2002 National Immunization Survey. Pediatrics, 115(1), e31–e37. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/1/e31.long [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Fridinger F., Grummer-Strawn L. (2002). Public perceptions on breastfeeding constraints. Journal of Human Lactation, 18(1), 227–235. Retrieved from http://jhl.sagepub.com/content/18/3/227.long [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littler C. (1997). Beliefs about colostrum among women from Bangladesh & their reasons for giving it to the newborn. Midwifery, 110(1308), 3–7. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9128564 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littman H., Medendorp S. V., Goldfarb J. (1994). The decision to breastfeed. The importance of fathers’ approval. Clinical Pediatrics, 33(4), 214–219. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8013168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBiondo-Wood G., Haber J. (2006). Nursing research: Methods and critical appraisal for evidence based practice. St. Louis, Mosby: Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes R. J., Chambers J. A. (2008). Supporting breastfeeding mothers: Qualitative synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(4), 407–427. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04618.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin F. E., Marascuilo L. A. (Eds.). (1990). Advanced nursing and healthcare research: Quantification approach. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell-Box K., Braun K. L. (2012). Fathers’ thoughts on breastfeeding and implications for a theory-based intervention. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 41(6), E41–E50. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran L., Gilad J. (2007). From folklore to scientific evidence: Breast-feeding and wet-nursing in Islam and the case of non-puerperal lactation. International Journal of Biomedical Science, 3(4), 251–257. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3614654/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky D. E., Kar S. B., Chaudhry A. S., Chen K. R., Shaheen M., Chickering K. (2002). Breastfeeding practices in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 3, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan S. S. C., Natarajan N., Bawa K. S. (2005). Maternal and neonatal factors adversely affecting breastfeeding in the perinatal period. Medical Journal Armed Forces India, 61(3), 216–219. Retrieved from http://medind.nic.in/maa/t05/i3/maat05i3p216.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ny P., Plantin L., Dejin-Karlsson E., Dykes A. K. (2008). Experience of Middle Eastern men living in Sweden of maternal and child health care and fatherhood: Focus-group discussions and content analysis. Midwifery, 24(3), 281–289. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17129643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien M., Shemilt I. (2003). Working fathers: Earning and caring. Manchester, United Kingdom: Equal Opportunities Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Pisacane A., Continisio G. I., Aldinucci M., D’Amora S., Continisio P. (2005). A controlled trial of the father’s role in breastfeeding promotion. Pediatrics, 116(4), e494–e498. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16199676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit D. F., Beck C. T. (2008). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott William &Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Premani Z., Kurji Z., Mithani Y. (2011). To explore the experiences of women on reasons in initiating and maintaining breastfeeding in urban area of Karachi, Pakistan: An exploratory study. ISRN Pediatrics, 2011, 514323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P. J., O’Callaghan M., Williams G. M., Najman J. M., Andersen M. J., Bor W. (2001). The effect of breastfeeding on child development at 5 years: A cohort study. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 37, 465–469. Retrieved from http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/eserv.php?pid=UQ:8593&dsID=pq-musp-01.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rempel L. A., Rempel J. K. (2011). The breastfeeding team: The role of involved fathers in the breastfeeding family. Journal of Human Lactation, 27(2), 115–121. Retrieved from http://jhl.sagepub.com/content/27/2/115.abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. A., Landers M. C., Hughes R. M., Binns C. W. (2001). Factors associated with breast feeding discharge and duration of breastfeeding at discharge. Journal of Paediatric Child Health, 37(3), 254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamim S., Jamalvi S. W., Naz F. (2006). Determinants of bottle use amongst economically disadvantaged mothers. Journal of Ayub Medical College, 18(1), 48–51. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16773970 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirima R., Gebre-Medhin M., Greiner T. (2001). Information and socioeconomic factors associated with early breastfeeding practices in rural and urban Morogoro, Tanzania. Acta Pediatrica, 90, 936–942. Retrieved from http://global-breastfeeding.org/pdf/tan2.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski J., Renfrew M. J., Pindoria S., Wade A. (2003). Support for breastfeeding mothers: A systematic review. Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 17(4), 407–417. 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2003.00512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M. L., Leathers S. J., Kelley M. A. (2004). Family characteristics associated with duration of breastfeeding during early infancy among primiparas. Journal of Human Lactation, 20(2), 196–205. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15117519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taveras E. M., Li R., Grummer-Strawn L., Richardson M., Marshell R., Rego V. H., Lieu T. A. (2004). Mothers’ and clinicians’ perspectives on breastfeeding counseling during routine preventative visits. Pediatrics, 113(5), e405–e411. http:///dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.5.e405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfberg A. J., Michels K. B., Shields W., O’Campo P., Bronner Y., Bienstock J. (2004). Dads as breastfeeding advocates: Results from a randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 191(3), 708–712. Retrieved from http://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(04)00488-0/fulltext [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]