Abstract

Aims/Introduction

The present study was to compare the efficacy and safety of subject‐driven and investigator‐driven titration of biphasic insulin aspart 30 (BIAsp 30) twice daily (BID).

Materials and Methods

In this 20‐week, randomized, open‐label, two‐group parallel, multicenter trial, Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled by premixed/self‐mixed human insulin were randomized 1:1 to subject‐driven or investigator‐driven titration of BIAsp 30 BID, in combination with metformin and/or α‐glucosidase inhibitors. Dose adjustment was decided by patients in the subject‐driven group after training, and by investigators in the investigator‐driven group.

Results

Eligible adults (n = 344) were randomized in the study. The estimated glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) reduction was 14.5 mmol/mol (1.33%) in the subject‐driven group and 14.3 mmol/mol (1.31%) in the investigator‐driven group. Non‐inferiority of subject‐titration vs investigator‐titration in reducing HbA1c was confirmed, with estimated treatment difference −0.26 mmol/mol (95% confidence interval −2.05, 1.53) (–0.02%, 95% confidence interval –0.19, 0.14). Fasting plasma glucose, postprandial glucose increment and self‐measured plasma glucose were improved in both groups without statistically significant differences. One severe hypoglycemic event was experienced by one subject in each group. A similar rate of nocturnal hypoglycemia (events/patient‐year) was reported in the subject‐driven (1.10) and investigator‐driven (1.32) groups. There were 64.5 and 58.1% patients achieving HbA1c <53.0 mmol/mol (7.0%), and 51.2 and 45.9% patients achieving the HbA1c target without confirmed hypoglycemia throughout the trial in the subject‐driven and investigator‐driven groups, respectively.

Conclusions

Subject‐titration of BIAsp 30 BID was as efficacious and well‐tolerated as investigator‐titration. The present study supported patients to self‐titrate BIAsp 30 BID under physicians’ supervision.

Keywords: Biphasic insulin aspart, Titration, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes in China has increasingly risen, reaching an estimated 100 million adults diagnosed with diabetes1. However, only about 40% of patients who received treatment had their blood glucose under control in China2. A total of 34% of patients with type 2 diabetes used insulin therapies in China. For these patients, the mean glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was just 8.21%, which is far from the HbA1c target of 53.0 mmol/mol (7%)3. A lack of regular dose adjustment for insulin users could partially account for this poorly controlled situation. Currently, most patients have their insulin dose titrated according to physicians’ discretion, which is a time‐ and cost‐consuming process4. Not to mention, it certainly becomes a challenge for the limited healthcare resources in China. Along with the importance of self‐management in diabetes being gradually realized, self‐measured plasma glucose (SMPG) and self‐titration have been shown to be helpful in lowering blood glucose and diabetes management for insulin users, and recommended by several clinical guidelines5, 6, 7. With self‐management including SMPG and self‐titration, patients might benefit physically and psychologically from improved awareness of the disease and conditions, the process of making informed decisions and the involvement of self‐care8.

In China, approximately one‐third of insulin using patients take premixed insulin to control blood glucose3, 9. Premixed insulin analog, such as biphasic insulin aspart 30 (BIAsp 30), has been shown to effectively improve blood glucose, has a better control of postprandial glucose in the Chinese population compared with human or basal insulin10, 11 and is associated with less total direct medical cost over 30 years (BIAsp 30 vs human premixed insulin −79,628 CNY)12. The improvement of postprandial glucose, mainly attributed to the rapid‐acting proportion of BIAsp 30, is of particular importance in Chinese people, in which a high proportion of postprandial hyperglycemia has been reported1. Despite the method of self‐titration based on SMPG being well established in basal insulin users, titration of premixed insulin has been generally considered more complicated and less investigated4. In a study carried out in Dutch patients with type 2 diabetes13, all participants were introduced to self‐monitoring and self‐titration of BIAsp 30, and most of them were able to manage self‐titration. However, the non‐randomized trial design limited the conclusion. The approach of subject‐driven titration was also applied in some other trials, where BIAsp 30 was administered twice daily (BID), such as INITIATEplus, 1‐2‐3 study and EuroMix study14, 15, 16. However, as none of these studies exclusively aimed to compare patient‐centered titration and investigator‐driven titration of BIAsp 30 BID, this issue, as of yet, remains elusive.

A randomized controlled trial was hence designed to compare the efficacy and safety of BIAsp 30 BID between a subject‐driven titration group and an investigator‐driven titration group in order to potentially provide an efficacious method of patient empowerment, through patient‐centred titration of BIAsp 30 treatment.

Materials and Methods

Trial Design and Participants

This was a 20‐week, randomized, open‐label, two‐group parallel, multicenter trial comparing the efficacy and safety of subject‐driven titration and investigator‐driven titration of BIAsp 30 BID in combination with oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) in patients with type 2 diabetes. An open‐label trial design was chosen, as blinding the randomized titration algorithm was not possible. The trial protocol and consent form were approved by independent ethics committees for each participating center. Signed informed consent was obtained from each participant before any trial‐related activities. The trial was carried out between 11 June 2012 and 31 January 2013 at 23 sites in China, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Guideline of Good Clinical Practice.

Men and women (age 18–65 years) with type 2 diabetes for at least 12 months, HbA1c 53.0–80.3 mmol/mol (7.0–9.5%), body mass index ≤35.0 kg/m2 and currently treated with premixed/self‐mixed human insulin (proportion of short‐acting insulin ≤30%) BID combined with metformin ± α‐glucosidase inhibitor for at least 3 months were eligible for inclusion. Patients treated with any insulin secretagogue, thiazolidinedione, dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors and glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists within the past 3 months were excluded from the trial. Other exclusion criteria included previous use of any insulin other than those listed in inclusion criteria, previous use of insulin intensification treatment more than 14 days, recurrent severe hypoglycemia or hypoglycemia unawareness, cardiovascular disease, impaired liver or renal function, pregnancy or breast‐feeding and mental incapacity. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrial.gov number NCT01618214.

Randomization

At the randomization visit (visit 2), eligible patients were randomized 1:1 to receive subject‐driven or investigator‐driven titration of BIAsp 30 BID by a telephone or web‐based randomization system, Interactive Voice/Web Response System, with stratification of HbA1c (53–64 mmol/mol [7.0–8.0%] and 65–80 mmol/mol [8.1–9.5%], all inclusive) and OADs (metformin monotherapy and metformin + α‐glucosidase inhibitor). BIAsp 30 (100 U/mL, 3 mL NovoMix® 30 Penfill®; Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) was administered subcutaneously, BID (morning and evening right before meal), using NovoPen® 4 (Novo Nordisk, Tianjin, China).

Treatment Administration and Titration

The treatment consisted of a 4‐week training period and a 16‐week maintenance period. Patients discontinued their previous treatment, and started BIAsp 30 BID (on a 1:1 basis from their previous premixed/self‐mixed human insulin) with OADs unchanged at randomization. Training on Guidelines for Insulin Education and Management17 was provided to all participants. Titration training on how to adjust the BIAsp 30 doses based on SMPG including the titration algorithm and how to adjust insulin dose to avoid hypoglycemia was exclusively provided to the subject‐driven group in the training period. Patients in the subject‐driven group were then asked to adjust BIAsp 30 doses themselves in the maintenance period. Patients in the investigator‐driven group adjusted BIAsp 30 doses only according to the directions from an investigator.

A glucose meter (OneTouch® UltraVue®; LifeScan, Milpitas, California, USA) was provided in the trial to measure blood glucose and was automatically calibrated to present plasma glucose values, generating SMPG values. SMPG was carried out on three consecutive days weekly in the first 8 weeks of treatment and then every 2 weeks in the last 12 weeks of treatment. The titration of the BIAsp 30 dose at breakfast/dinner was based on the lowest pre‐dinner/breakfast SMPG value measured from three preceding days, following the titration algorithm in Table 1, 18, 19.

Table 1.

Algorithm for titration of biphasic insulin aspart 30

| Before breakfast/dinner SMPG | Dose adjustment (U) | |

|---|---|---|

| mmol/L | mg/dL | |

| <4.4 | <80 | −2 |

| 4.4–6.1 | 80–100 | 0 |

| 6.2–7.8 | 111–140 | +2 |

| 7.9–10 | 141–180 | +4 |

| >10 | >180 | +6 |

SMPG, self‐measured plasma glucose.

A detailed visit schedule is shown in Table 2. In the training period (visit 2–6), there was one clinical visit and two phone contacts scheduled for the subject‐driven group after the randomization visit, whereas there were two clinical visits and two phone contacts for the investigator‐driven group. These mandatory contacts were to assure the quality of the training. In the maintenance period (visit 7–16), the subject‐driven group had two mandatory clinical visits (visit 10 and 12) before the final visit, whereas the investigator‐driven group had four mandatory clinical visits (visit 8, 10, 12 and 14) before the final visit, and were required to call the site in the week without a scheduled on‐site visit (visit 7, 9, 11, 13 and 15) if one of the doses had been changed at the previous visit. Blood samples were drawn to assess the HbA1c at the screening visit, visit 6, 10, 12, and the final visit. HbA1c was analyzed by a central laboratory. Any safety issues were reported and recorded at each clinical visit and phone contact. Patients could call the site at any time, if deemed necessary.

Table 2.

Visit schedule

| Visit no. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of visit (weeks) | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 |

| Subject‐driven | O | O | P | P | P* | O | P* | O | P* | O | P* | O | ||||

| Investigator‐driven | O | O | P | O | P | O | P# | O | P# | O | P# | O | P# | O | P# | O |

O, on‐site visit; P, phone contact (subject must call the site); P*, phone contact (subject can call the site at any time, if deemed necessary by the subject); P#, phone contact (subject must call the site if one of the doses has been changed at the previous visit. However, subjects can call the site at any time if deemed necessary by the subjects).

Trial End‐Points

The primary end‐point was the change from baseline in HbA1c after 20 weeks of treatment. Secondary end‐points included the percentages of patients achieving HbA1c <53.0 mmol/mol (7.0%) after 20 weeks of treatment, the percentages of patients achieving HbA1c <53.0 mmol/mol (7.0%) without severe + minor hypoglycemic episodes during the last 12 weeks of treatment, change from baseline in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) after 20 weeks of treatment, prandial plasma glucose (PPG) increment and eight‐point SMPG profile after 20 weeks of treatment.

As safety end‐points, all adverse events (AEs), hypoglycemic episodes, physical examinations, vital signs, laboratory assessments and electrocardiograms were recorded, as well as changes in bodyweight and total daily insulin dose. Plasma glucose (PG) value <3.1 mmol/L (56 mg/dL) (regardless of symptoms) was defined as minor hypoglycemia, whereas requiring third‐party assistance was defined as severe hypoglycemia, both of which were included in confirmed hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemic events that occurred between 00.01 and 05.59 h (both inclusive) were classified as nocturnal.

The overall impact of diabetes treatment evaluated by patients was assessed by the validated questionnaire, Treatment‐Related Impact Measures for Diabetes in Chinese (scale 0–100), including five domains: treatment burden, daily life, diabetes management, compliance and psychological health. The greater score represents less impact of diabetes treatment on the patients20.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was determined using a t‐statistic under the assumption of a one‐sided test of size 2.5% and a zero mean treatment difference, with a standard deviation of 1.2% for HbA1c. Assuming that 15% of subjects were excluded from the per‐protocol analysis set, 338 randomized subjects were required to achieve 80% power of non‐inferiority. Statistical analysis of HbA1c, FPG, PPG increment, eight‐point SMPG, HbA1c responder and patient‐reported outcomes was carried out in all randomized patients (full analysis set). The last observation carried forward was used to impute missing values, and applied for all efficacy end‐points. Change in HbA1c was analyzed using a linear mixed model, with treatment, HbA1c strata, previous OAD strata, interaction between HbA1c strata and previous OAD strata as fixed factors, and baseline HbA1c as covariates. The non‐inferiority of subject‐driven compared with investigator‐driven titration of BIAsp 30 in the change of HbA1c could be confirmed with a non‐inferiority limit of 0.4%. Changes in other efficacy end‐points were analyzed with a similar model used for the primary end‐point. The number of hypoglycemic episodes were analyzed in all patients exposed to treatment (safety analysis set) using a negative binomial regression model. Post‐hoc analysis included percentages of patients achieving the HbA1c target without confirmed hypoglycemic events throughout 20 weeks of treatment and hypoglycemic episodes that occurred in patients achieving the HbA1c target.

Results

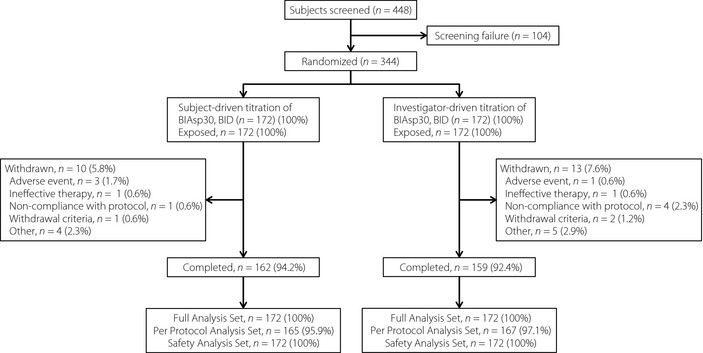

Of the 448 patients screened in the trial, 344 were eligible and randomized into two groups, subject‐titration (172) and investigator‐titration (172), all of which were exposed to treatment (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the two groups were comparable at screening (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Subjects’ disposition.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the full analysis set

| Subject‐driven | Investigator‐driven | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 172 | 172 | 344 |

| Male | 93 (54.1%) | 71 (41.3%) | 164 (47.7%) |

| Age (years) | 54.8 (7.3) | 53.4 (7.5) | 54.1 (7.4) |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 10.5 (6.2) | 10.6 (6.2) | 10.6 (6.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.8 (3.3) | 25.5 (3.0) | 25.6 (3.1) |

| Previous OAD treatment | |||

| Metformin monotherapy | 142 (82.6) | 142 (82.6) | 284 (82.6) |

| Metformin + α‐glucosidase inhibitor | 30 (17.4) | 30 (17.4) | 60 (17.4) |

Data are shown as n (percentages %) for sex and previous oral antidiabetic drug (OAD) treatment, and mean (standard deviation) for age, diabetes duration and body mass index (BMI).

Efficacy

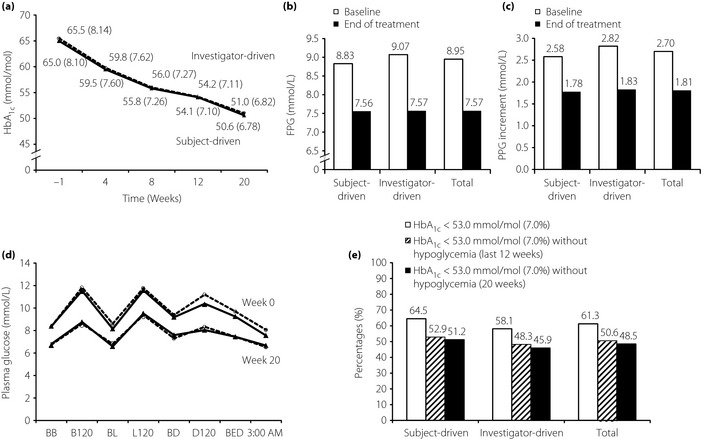

HbA1c (mean ± standard deviation) decreased throughout the 20 weeks of treatment (Figure 2a), from 65.3 ± 7.2 mmol/mol (8.12 ± 0.65%) at baseline to 50.8 ± 8.5 mmol/mol (6.80 ± 0.78%) at the end of trial in the overall cohort. The estimated mean changes in HbA1c (least squares mean ± standard error) were −14.5 ± 0.7 mmol/mol (−1.33 ± 0.06%) for the subject‐driven group and −14.3 ± 0.6 mmol/mol (–1.31 ± 0.06%) for the investigator‐driven group. The treatment difference (subject‐driven group vs investigator‐driven group) was −0.26 mmol/mol (95% confidence interval [CI] −2.05, 1.53) (–0.02%, 95% CI –0.19, 0.14). Non‐inferiority was therefore achieved, which was further supported by per‐protocol set analysis, with the treatment difference of −0.07 mmol/mol (95% CI −1.84, 1.70; –0.01%, 95% CI –0.17, 0.16).

Figure 2.

Efficacy end‐points from baseline to the end of treatment. Changes of mean levels of (a) glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), (b) fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and (c) postprandial glucose (PPG) increment with (d) last observation carried forward (full analysis set). (D) Eight‐point self‐measured plasma glucose profile at week 0 and week 20 with last observation carried forward (full analysis set); data are shown as mmol/mol (%) for HbA1c. (e) Percentages of patients achieving the HbA1c target of <7% at week 20, achieving HbA1c targets without confirmed hypoglycemic events in the last 12 months or throughout the trial (20 weeks; last observation carried forward, full analysis set). Triangle with solid line, subject‐driven group; circle with dash line, investigator‐driven group. B120, 120 min after breakfast; BB, before breakfast; BD, before dinner; BED, at bedtime; BL, before lunch; D120, 120 min after dinner; L120, 120 min after lunch.

The estimated mean changes of FPG were –1.36 ± 0.15 mmol/L and –1.38 ± 0.15 mmol/L for the subject‐driven group and investigator‐driven group, respectively, with a difference of 0.02 mmol/L (95% CI –0.40, 0.43; P = 0.94; Figure 2b). The estimated mean change of PPG increment (average of three meals of a day) were –0.91 ± 0.13 and –0.93 ± 0.13 mmol/L for the subject‐driven group and investigator‐driven group, respectively, with a difference of 0.02 mmol/L (95% CI –0.35, 0.39; P = 0.9; Figure 2c).

Treatment with BIAsp 30 for 20 weeks improved eight‐point SMPG profiles in both the subject‐driven and investigator‐driven groups (Figure 2d). Blood glucose levels were reduced at all eight time‐points in both groups, compared with baseline. The most substantial decreases in the SMPG profiles were observed at 120 min after breakfast (PG reduction 2.90 ± 4.34 and 3.18 ± 3.81 mmol/L in the subject‐driven and investigator‐driven groups, respectively). For eight‐point SMPG profiles at the end of treatment, overall parallelism between the two groups was confirmed with a P‐value of 0.46.

At the end of treatment, patients achieving HbA1c <53.0 mmol/mol (7.0%) were comparable in the subject‐driven group (64.5%) and in the investigator‐driven group (58.1%), with no significant difference (P = 0.27). The similarity was also shown for the percentages of patients achieving HbA1c target without confirmed hypoglycemia throughout the trial (51.2% for the subject‐driven group and 45.9% for the investigator‐driven group, P = 0.23; Figure 2e). Likewise, similar percentages of HbA1c responders without confirmed hypoglycemia in the last 12 weeks were reported in the two groups (Figure 2e).

Safety

During the trial, AEs were reported by 19.8 and 30.8% of patients in the subject‐driven and investigator‐driven group, respectively, with the most frequently reported AE being infections and infestations (in total reported by 13.4% of patients). The majority of AEs were mild in severity. A total of four patients withdrew from the trial as a result of AEs (three in the subject‐driven group and one in the investigator‐driven group). All reported treatment‐emergent serious AEs (four events reported by four patients in the subject‐driven group and eight events reported by seven patients in the investigator‐driven group) were assessed as unlikely to be related to the trial product. No deaths were reported.

In general, the rates of confirmed hypoglycemia were comparable in the subject‐driven group (1.71 events/patient‐year) and in the investigator‐driven group (1.68 events/patient‐year), with a P‐value of 0.98. Severe hypoglycemic events were experienced by one patient (0.6%, 1 event) in the subject‐driven group and one patient (0.6%, 1 event) in the investigator‐driven group (Table 4). No severe nocturnal hypoglycemia was reported in any of the groups, whereas six and 17 minor nocturnal events were recorded in the subject‐driven and investigator‐driven groups, respectively. Among patients achieving the HbA1c target of <53.0 mmol/mol (7.0%), one episode of severe hypoglycemia was reported in each group (Table 4). The incidences of minor or nocturnal hypoglycemia were not more frequently reported by the HbA1c responders, but rather remained similar, when compared with those in all patients in the safety analysis set of each group.

Table 4.

Summary of treatment‐emergent hypoglycemic episodes

| Subject‐driven | Investigator‐driven | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 172 | 172 | 344 |

| Severe | 0.6/0.02 | 0.6/0.02 | 0.6/0.02 |

| Minor | 22.1/1.70 | 23.8/1.66 | 23.0/1.68 |

| Nocturnal | 23.3/1.10 | 20.9/1.32 | 22.1/1.21 |

| Patient achieving HbA 1c <53.0 mmol/mol (7.0%) | |||

| n | 111 | 100 | 211 |

| Severe | 0.9/0.02 | 1.0/0.03 | 0.9/0.02 |

| Minor | 21.6/1.43 | 21.0/0.91 | 21.3/1.18 |

| Nocturnal | 20.7/1.12 | 16.0/0.78 | 18.5/0.96 |

Data are shown as percentages of patients having events (%)/rate (events/patient‐year).

Bodyweight was slightly increased without statistical difference between the two groups (Table 5). The increases of insulin dose were similar between the two groups (Table 5).

Table 5.

Change in bodyweight, insulin dose and patient report outcomes

| Subject‐driven | Investigator‐driven | |

|---|---|---|

| Bodyweight (kg) | ||

| Baseline | 70.3 ± 11.3 | 69.5 ± 11.6 |

| Week 20 | 72.0 ± 11.4 | 71.1 ± 11.8 |

| Treatment difference at week 20 | 0.08 (95% CI –0.51, 0.67), P = 0.79 | |

| Insulin dose (U/kg) | ||

| Week 1 | 0.52 ± 0.17 | 0.56 ± 0.18 |

| Week 20 | 0.81 ± 0.30 | 0.82 ± 0.27 |

| Patient report outcomes | ||

| Total score | ||

| Week 0 | 62.7 ± 11.3 | 64.0 ± 12.9 |

| Week 20 | 70.0 ± 11.5 | 71.2 ± 12.4 |

| Treatment difference at week 20 | –0.59 (95% CI –2.92, 1.74), P = 0.62 | |

| Subscales | ||

| Treatment burden | ||

| Week 0 | 50.9 ± 14.1 | 52.2 ± 16.8 |

| Week 20 | 57.5 ± 15.7 | 59.2 ± 16.7 |

| Daily life | ||

| Week 0 | 69.9 ± 15.7 | 70.2 ± 18.8 |

| Week 20 | 75.2 ± 16.2 | 75.7 ± 16.2 |

| Diabetes management | ||

| Week 0 | 45.9 ± 12.4 | 49.4 ± 18.4 |

| Week 20 | 56.0 ± 15.2 | 59.3 ± 17.2 |

| Compliance | ||

| Week 0 | 67.8 ± 17.3 | 68.3 ± 16.7 |

| Week 20 | 75.1 ± 15.4 | 76.5 ± 17.7 |

| Psychological health | ||

| Week 0 | 76.0 ± 17.1 | 76.3 ± 17.8 |

| Week 20 | 82.7 ± 14.8 | 82.3 ± 14.4 |

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. CI, confidence interval.

Patient‐Reported Outcomes and Healthcare Resource Utilization

Overall patient evaluation of diabetes treatment was improved (Table 5). There was no statistically significant difference in total ratings between the groups, with estimated mean changes of 6.82 ± 0.84 and 7.41 ± 0.84 for the subject‐driven and investigator‐driven groups, respectively, and the difference being –0.59 (95% CI –2.92, 1.74; P = 0.62). No statistically significant differences were observed in the ratings for each of the five subscales either.

Compared with the investigator‐driven group, patients in the subjects‐driven group had fewer visits to the clinic, as defined by the protocol, and similar numbers of telephone consultations and additional contacts that were not mandatory per protocol (Table 6).

Table 6.

Healthcare resource utilization

| Subject‐driven | Investigator‐driven | |

|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 172 | 172 |

| Contact by reason | ||

| Mandatory | 172 (100.0), 1350, 0.40 | 172 (100.0), 1852, 0.55 |

| Additional | 149 (86.6), 644, 0.19 | 166 (96.5), 695, 0.21 |

| Contact by type | ||

| Telephone | 172 (100.0), 973, 0.29 | 171 (99.4), 1023, 0.30 |

| Visit to the clinic | 172 (100.0), 1021, 0.30 | 172 (100.0), 1524, 0.45 |

Number of patients (percentage of patients), number of contacts, mean number of contacts per patient week.

Discussion

The present study showed that, after switching human insulin to BIAsp 30 BID, subject‐driven titration was non‐inferior to investigator‐driven titration in reducing HbA1c. The improvement of FPG, PPG increment, and eight‐point SMPG profile and hypoglycemic incidences were all similar in both groups. This was to our knowledge the first head‐to‐head comparison with patient‐titration and investigator‐titration of a premixed formulation BIAsp 30 BID in a Chinese population, providing direct evidence showing that patient‐titration of BIAsp 30 BID is as effective and well tolerated as investigator‐titration. This trial gave an example that can be followed in clinical practice; that is, after adequate training (including titration algorithm, note of hypoglycemia and how to handle it), patients could be able to self‐adjust the premixed insulin doses with similar efficacy and safety profiles as upon investigator's discretion. These data are important for both patients who are insufficiently involved in self‐management of their conditions and caregivers who are considering empowering patients.

A notable decrease of HbA1c (14.5 mmol/mol [1.33%]) was observed in the subject‐driven titration group in the current trial. As a result of the improved glycemic control, 64.5% patients in subject‐driven group met the HbA1c target. Effective glycemic control was also reported in other trials where dose adjustment of BIAsp 30 BID was self‐decided by patients13, 14, 15, 16. The reduction of HbA1c was 1.4–2.5% in those trials, which was similar to that reported in the present study. The positive effect with reduced HbA1c levels in these trials explicitly showed that patient titration of BIAsp 30 BID was feasible. The present study has further shown that subject‐driven titration of BIAsp30 BID was non‐inferior to investigator‐driven titration in reducing HbA1c, suggesting a possibility to empower patients to self‐titration without compromising the effectiveness. Once weekly or every 2 weeks titration of BIAsp30 was applied in the present trial with proven efficacy, in line with the recommendation in a practical guidance, and can be translated into clinical practice18.

Several investigations have suggested that intensive glycemic control was associated with a higher risk of hypoglycemia21, 22, 23, 24. The concerns for hypoglycemia could be a barrier when optimizing insulin dose, resulting in disappointing glycemic control4. It was valuable in this trial to see that the HbA1c target of <53.0 mmol/mol (7.0%) was not achieved at the expense of increased risk of hypoglycemia in the investigator‐driven group, and particularly, in the subject‐driven group as well. The incidences of severe and nocturnal hypoglycemia were similar to those reported in HbA1c responders in the subject‐driven group. Most patients who met the HbA1c target experienced no hypoglycemic events throughout the trial (79% in both groups). This showed that titration of insulin dose to achieve HbA1c target was not accompanied with increased risk of hypoglycemia. No obvious differences regarding safety issues were observed between the two groups, suggesting that empowering patients to self‐titration did not raise additional safety concerns.

Without major safety concerns, the total daily insulin dose was uptitrated from 0.5 to 0.8 U/kg as the final dose. This insulin dose was in line with the Initiation of Insulin to Reach A1c Target study (INITIATE Study) and Yang's trial25, 26. The two groups ended with similar doses, suggesting that patients successfully managed the dose titration themselves after training, and adjusted insulin dose as required to achieve good control of blood glucose.

Empowering patients to self‐titration allows treatment to be adjusted in a timely manner along with change of lifestyle, meanwhile it might improve treatment adherence and glycemic control27. As shown by the present study, patient‐titration was associated with improved treatment satisfaction. It is interesting to note that diabetes management and compliance were the most improved two subscales in Treatment‐Related Impact Measures for Diabetes evaluation. Considering the limited healthcare resources in China, the present study might be important. It was not surprising to see lower mandatory contact numbers and rates according to the protocol. Nevertheless, it was noticed that no more additional contacts were called for in the subject‐driven group, showing that patients were capable of making decisions and self‐managing their disease. To be noted is that the titration was successfully managed by the patients in the subject‐driven group after they gained sufficient training. The training in the present trial played a role in effective dose adjustment in the subject‐driven group.

The trial participants are representative of the general population using premixed insulin in China. However, caution needs to be taken when considering applying self‐titration in elderly patients, who might not be willing or able to learn and comply with the titration algorithm. There were some limitations to this trial. It was necessary to include some mandatory contacts in the trial design, in order to make necessary assessments (such as HbA1c) and record safety information (such as hypoglycemia) in both the subject‐driven and investigator‐driven groups. These contacts, even without providing any advice regarding titration, might add bias to the result of the subject‐driven group. Furthermore, the present study focused on patients who were experienced with insulin treatment using insulin BID. Further study needs to be carried out to investigate whether self‐titration by patients can be similarly well tolerated and effective among insulin‐naive patients.

In conclusion, the present study showed that subject‐driven titration of BIAsp30 BID was as effective and well tolerated as investigator‐driven titration under physicians’ supervision, shedding light on the possibility of patient empowerment to a premix formulation of insulin administration twice daily.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Novo Nordisk (China). All authors significantly contributed to the trial operation, data collection, discussion of the data, and the preparation, review and final approval of the manuscript. Additional gratitude should be given to Lili Pan, Ningning Qu and Cai Tang from Novo Nordisk (China) for their medical, statistical, and editorial assistance. Parts of this study were orally presented in 17th Chinese Diabetes Society Annual Meeting, 20–23 November 2013, Fuzhou, China; and presented in poster form at the International Diabetes Federation World Diabetes Congress, 2–6 December 2013, Melbourne, Australia.

J Diabetes Investig 2016; 7: 85–93

References

- 1. Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, et al Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1090–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Xu Y, Wang L, He J, et al Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults. JAMA 2013; 310: 948–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ji LN, Lu JM, Guo XH, et al Glycemic control among patients in China with type 2 diabetes mellitus receiving oral drugs or injectables. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 602. doi:10.1186/1471‐2458‐13‐602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khunti K, Davies MJ, Kalra S. Self‐titration of insulin in the management of people with type 2 diabetes: a practical solution to improve management in primary care. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013; 15: 690–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Diabetes Association . Standards of medical care in diabetes–2013. Diabetes Care 2013; 36(Suppl. 1): S11–S66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Collaborating Centre for for Chronic Conditions . Type 2 Diabetes: National Clinical Guideline for Management in Primary and Secondary Care. Royal College of Physicians, London, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Handelsman Y, Mechanick JI, Blonde L, et al American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan. Endocr Pract 2011; 17(Suppl. 2): 1–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Empowerment and self‐management of diabetes. Clinical Diabetes 2013; 22: 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gao Y, Guo XH, Vaz JA. Biphasic insulin aspart 30 treatment improves glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes in a clinical practice setting: Chinese PRESENT study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009; 11: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gao Y, Guo XH. Switching from human insulin to biphasic insulin aspart 30 treatment gets more patients with type 2 diabetes to reach target glycosylated hemoglobin < 7%: the results from the China cohort of the PRESENT study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010; 123: 1107–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang W, Xu X, Liu X, et al Treat‐to‐target comparison between once daily biphasic insulin aspart 30 and insulin glargine in Chinese and Japanese insulin‐naive subjects with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin 2013; 29: 1599–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xiao J, Bian X, Zhang Y, et al Cost‐effectiveness of switching to biphasic insulin aspart from human premix insulin in people with type 2 diabetes in China. Value Health 2014; 17: A242. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ligthelm RJ. Self‐titration of biphasic insulin aspart 30/70 improves glycaemic control and allows easy intensification in a Dutch clinical practice. Prim Care Diabetes 2009; 3: 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garber AJ, Wahlen J, Wahl T, et al Attainment of glycaemic goals in type 2 diabetes with once‐, twice‐, or thrice‐daily dosing with biphasic insulin aspart 70/30 (The 1‐2‐3 study). Diabetes Obes Metab 2006; 8: 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kann PH, Wascher T, Zackova V, et al Starting insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: twice‐daily biphasic insulin Aspart 30 plus metformin versus once‐daily insulin glargine plus glimepiride. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2006; 114: 527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oyer DS, Shepherd MD, Coulter FC, et al A(1c) control in a primary care setting: self‐titrating an insulin analog pre‐mix (INITIATEplus trial). Am J Med 2009; 122: 1043–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chinese Diabetes Society . Guidelines for Insulin Education and Management. China. Science & Technology Press, Tianjin, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Unnikrishnan AG, Tibaldi J, Hadley‐Brown M, et al Practical guidance on intensification of insulin therapy with BIAsp 30: a consensus statement. Int J Clin Pract 2009; 63: 1571–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. European Medicines Agency . Product information. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/includes/document/document_detail.jsp?webContentId=WC500029441&mid=WC0b01ac058009a3dc. (last accessed Jan. 2015)

- 20. Brod M, Hammer M, Christensen T, et al Understanding and assessing the impact of treatment in diabetes: the Treatment‐Related Impact Measures for Diabetes and Devices (TRIM‐Diabetes and TRIM‐Diabetes Device). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009; 7: 83. doi:10.1186/1477‐7525‐7‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group . Intensive blood‐glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352: 837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2545–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, et al Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang W, Ji Q, Zhu D, et al Biphasic insulin aspart 30 three times daily is more effective than a twice‐daily regimen, without increasing hypoglycemia, in Chinese subjects with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on oral antidiabetes drugs. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 852–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raskin P, Allen E, Hollander P, et al Initiating insulin therapy in type 2 Diabetes: a comparison of biphasic and basal insulin analogs. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. White RD. Patient empowerment and optimal glycemic control. Curr Med Res Opin 2012; 28: 979–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]