Abstract

Primary pulmonary non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) is very rare. It represents less than 1% of all NHL, and 0.5–1% of all primary pulmonary malignancies. Almost all cases of primary pulmonary NHL originate from B‐cell lineage. We present a case of a 53‐year‐old man with primary extranodal NK/T‐cell lymphoma of the bronchus and lung, presented progressive dyspnea caused by right lower lung consolidation, and pleural effusion. Initial chest computed tomography suggested advanced lung cancer. Bronchofiberscopy showed a polypoid tumor on which a biopsy was performed. Histologically, the diffusely infiltrative atypical cells were positive for cytoplasmic CD3, CD56, granzyme B, and negative for cytokeratin, CD20 immunostains, suggesting NK/T cell lineages. In situ hybridization for Epstein‐Barr virus encoded ribonucleic acid (EBER) was positive. Herein, we discuss the clinicopathological features of this case and review the literature on primary extranodal NK/T‐cell lymphoma of the lung. Compared with other patients, who died after the first cycle of chemotherapy and/or within three months, our patient had longer survival under aggressive chemotherapy and auto‐peripheral blood stem cell transplantation.

Keywords: Lymphoma, lung and/or bronchus, natural killer/T‐cell

Introduction

Primary pulmonary lymphoma is defined as clonal lymphoid proliferation affecting lung parenchyma and/or bronchi in a patient with no detectable extrapulmonary involvement at diagnosis or during the subsequent three months.1 Primary pulmonary lymphoma is very rare. Approximately 70–90% of cases are low‐grade B‐cell lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type. Patients with this entity most commonly present an asymptomatic mass discovered on chest radiograph.2 High grade diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma comprises 5–20% of all primary pulmonary lymphomas. Some patients complain of systemic “B” symptoms, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Imaging often shows solid and multiple masses.3 Primary pulmonary NK/T‐cell lymphoma (NKTCL) is extremely rare and highly aggressive. We report a case of primary extranodal NKTCL of the bronchus and lung, presented with a polypoid tumor involving the mediastinum, mimicking a small cell carcinoma.

Case report

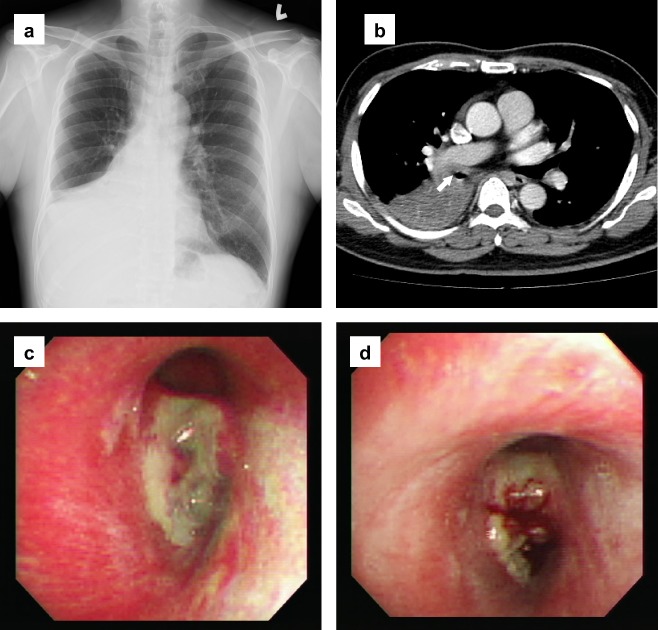

Our case, a 53‐year‐old male, had smoked one pack of cigarettes per day for five years. He complained of progressive dyspnea and a productive cough lasting for four months. He also had a persistent low‐grade fever, but denied weight loss, night sweats or hemoptysis in recent weeks. There was no nasal obstruction and no mass found in the nasal cavity. A chest radiograph showed lung consolidation over the right lower lung field, associated with pleural effusion (Fig 1a). Laboratory examination revealed a white blood cell count of 4.16 × 103/uL, hemoglobin 15.1 g/dL, platelets 128 × 103/uL, and mild elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 247 U/L (normal range 95–205 U/L). Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed a tumor in the right main bronchus and lung, with mediastinum involvement and regional lymphadenopathy, leading us to suspect an advanced lung cancer, such as a small cell carcinoma (Fig 1b). Bronchofiberscopy showed a polypoid tumor with erosion over the right main bronchus (Fig 1c,d). A biopsy was taken.

Figure 1.

(a) Chest radiograph showed lung consolidation over the right lower lung field with moderate pleural effusion. (b) Chest computed tomography revealed a tumor in the right main bronchus (arrow) and right lower lobe of the lung, with mediastinum and adjacent organ involvement. (c) Bronchofiberscopy showed a polypoid tumor with whitish tissue coating and erosion over the orifice of the right main bronchus. (d) Easy bleeding of the tumor after bronchofiberscopic biopsy.

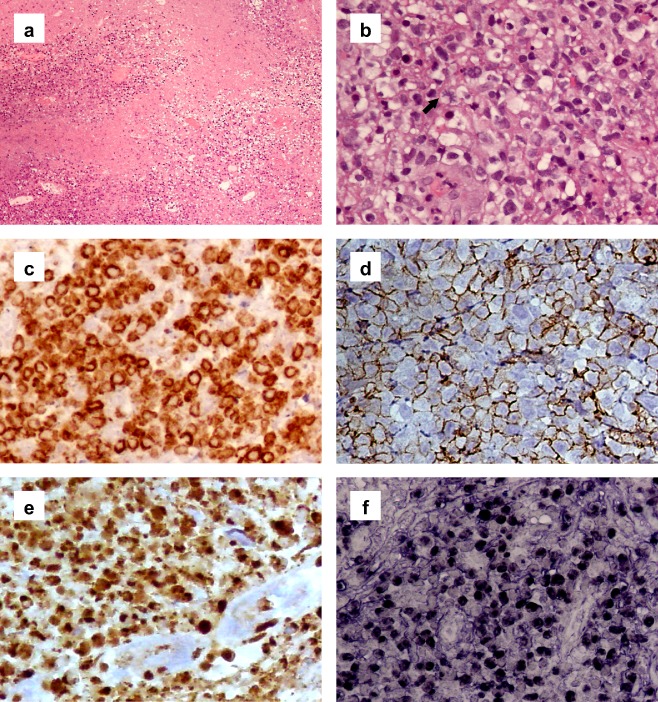

Histologically, the tissue showed extensive necrosis (Fig 2a). The tumor cells were small to medium‐sized with irregular nuclear contours, condensed chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and pale cytoplasm. Mitotic figures were easily found, including atypical forms (Fig 2b). An angiocentric growth pattern and angiodestruction were not found in this small biopsy specimen. Using immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells were positive for CD2, cytoplasmic CD3ε (Fig 2c), CD56 (Fig 2d), and granzyme B (Fig 2e), but were negative for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3), CD4, CD8, and CD20, indicating NK/T cell lineages of the neoplastic cells. The neoplastic NK/T cells were positive for Epstein‐Barr virus encoded ribonucleic acid (EBER) in situ hybridization (Fig 2f), but no CD20 positive B‐cells were present. A bone marrow biopsy revealed no abnormalities. Based on the morphologic and immunophenotypic findings, as well as clinical information, a diagnosis of primary pulmonary NKTCL was made.

Figure 2.

(a) Tissue showed extensive necrosis (hematoxylin & eosin [H&E] stain, magnification, 100x). (b) The diffusely infiltrative small to medium‐sized tumor cells had irregular nuclear contours, condensed chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and pale cytoplasm. Mitotic figures were easily found, including atypical form (arrow) (H&E 400x). (c) By immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells were positive for cytoplasmic CD3ε (400x). (d) Positive for CD56 (400x). (e) Positive for granzyme B (400x). (f) In situ hybridization for Epstein‐Barr virus encoded ribonucleic acid was positive (400x).

One week later, the patient received first line chemotherapy with combined regimens of cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOP). The follow up chest CT showed a partial response. After three cycles of CHOP therapy, CT revealed progressive disease with bilateral pleural effusion and increased tumor infiltration. Second line chemotherapy combining cisplatin, etoposide, cytarabine and solu‐medrol was administered for two cycles followed by auto‐peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (PBSCT). Laboratory examination revealed pancytopenia, a white blood cell count of 0.21 × 103/uL, hemoglobin 9.9 g/dL, platelets 23 × 103/uL, and a marked elevation of LDH (1148 U/L). The patient developed neutropenic fever, septic shock, multiple organ failure, and died seven months after initial diagnosis.

Discussion

Primary pulmonary NKTCL is extremely rare. A review of the literature found only a few reported cases in Japan, Korea, the United States, China, and Taiwan.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 The geographic distribution is similar to extranodal NKTCL, nasal type, which is prevalent in Asia, and central, and South America.10 In a summary of the clinicopathological features of these cases (Table 1), we found that most patients initially present with a fever, cough, and dyspnea, associated with unilateral or bilateral pulmonary consolidation and pleural effusion. Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy may be present. Histologically, most cases were found to have angiocentric and angiodestructive growth patterns with extensive necrosis, although these features may not be identified in a small biopsy specimen. The typical immunophenotype was CD2+, CD56+, surface CD3‐, and cytoplasmic CD3ε+. Cytotoxic molecules, including granzyme B, TIA‐1, and perforin, were positive. CD20, a B‐cell marker, was consistently negative. Almost all cases were positive for the Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV), proven either by elevated plasma EBV DNA levels or in situ hybridization for EBER.

Table 1.

Summary of the clinicopathological features and outcome of primary extranodal NK/T‐cell lymphoma of lung

| Case number | Age/ Gender | Clinical features | Image studies | Cell size | Necrosis | AC/AD | Immunophenotype | Treatment and outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 14 | 17/ F |

Dyspnea EBV (+), LDH↑ |

Multiple nodules in both lungs, bilateral PE, LAP (‐) |

Medium to large |

Present | AC + | CD2+, cytoplasmic CD3+, CD16+, CD56+, LCA+ | Died after first cycle of C/T |

| Case 2 5 | 50/ M |

Fever, general fatigue, EBV (+) |

Multiple nodules in both lungs LAP (+) |

Medium to large |

N/A | N/A | Cytoplasmic CD3+, CD56+, CD20‐ |

Pulse therapy Survived 29 days |

| Case 3 6 | 34/ F |

Fever, night sweating dyspnea, cough, EBV (+), LDH↑ |

Left lower lobe consolidation PE, LAP (‐) |

N/A | Extensive | N/A |

Cytoplasmic CD3 +, CD56+, CD20‐ |

Died after first cycle of C/T |

| Case 47 | 72/ F |

Fever, cough, shortness of breath |

Bilateral lung consolidation, right PE, LAP (‐) |

Small | N/A |

AC + AD + |

CD3+, CD56+, LCA+, CD20‐ | Died * |

| Case 5 & 68 | Young/ F |

Fever, cough, EBV (+) |

Bilateral lung consolidation, bilateral PE, LAP (‐) |

N/A | Present |

AC + AD + |

CD3+, CD56+, CD20‐, TIA‐1 + , perforin+, |

Died †

Survived 40 & 66 days |

| Case 79 | 80/ M |

Cough, splenomegaly, EBV (+), LDH↑ |

Left lower lobe mass‐like lesion, pulmonary nodules, LAP (+) | Medium | Present | N/A | Cytoplasmic CD3+, CD56+, CD30+, CD20‐ |

Introduction C/T Died three weeks after C/T |

| Our case | 53/ M |

Fever, dyspnea, cough, EBV (+), LDH↑ |

Right lower lobe consolidation, right PE, LAP (+), polypoid mass over bronchus |

Small to medium |

Extensive |

AC ‐ AD ‐ |

CD2+, cytoplasmic CD3+,CD56+, granzyme B + , CD20‐ |

C/T (CHOP+ESHAP) PBSCT Survived seven months |

*Diagnosis was made by post mortem examination, duration of survival unknown. †The treatment information was not available in English literature. AC, angiocentric; AD, angiodestruction; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, vincristine and prednisolone; C/T, chemotherapy; EBV, Epstein‐Barr virus; ESHAP, cisplatin, etoposide, cytarabine and solu‐medrol; LAP, lymphadenopathy; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; N/A, not available; PBSCT, peripheral blood stem cell transplantation; PE, pleural effusion.

Extranodal NKTCL occurring outside the nasal cavity is highly aggressive, with a short survival and poor response to therapy.11 A review of previous cases showed rapid disease progression and poor prognosis (Table 1). Patients died after the first cycle of chemotherapy and/or within three months after diagnosis. Our case had longer survival under aggressive chemotherapy and auto‐PBSCT, a previous unreported treatment of primary pulmonary NKTCL. An elevated LDH was found in our patient, as in three of the previous cases. As our patient's disease progressed, his serum LDH level of 247 U/L increased to 602 U/L and then to 1148 U/L. It also increased in pleural effusion (850 U/L to 3521 U/L). Our findings, as well as those of others, might suggest a correlation between high LDH levels and poor prognosis.12

Extranodal NKTCL of the lung is highly aggressive, and a correct diagnosis is crucial to determine prognosis. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LYG) involves the lung in over 90% of all cases.13 Morphologically, lymphoid infiltrate surrounds the vessel with angiodestruction and necrosis resembles NKTCL. The neoplastic cells of LYG are B cells. In our case, the CD3ε, CD56, and granzyme B positive tumor cells were also positive for EBER in situ hybridization. There were no CD20 positive B‐cells present. This would distinguish LYG from NKTCL. Small cell carcinoma is another important differential diagnosis in our patient. The neoplastic cells of small cell carcinoma can also be positive for CD56, and histologically, small to medium‐size with inconspicuous nucleoli resembling NKTCL. In our case, the tumor cells were positive for CD3ε and granzyme B, and negative for AE1/AE3, excluding a diagnosis of small cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

At this moment, there is no recommended treatment for primary pulmonary NKTCL because of the extreme rarity of this entity. A novel regimen of dexamethasone, methotrexate, ifosfamide, L‐asparaginase, and etoposide has been shown to have a response rate as high as 80% in NKTCL patients.14 Our patient was treated with aggressive chemotherapy and auto‐PBSCT and survived for seven months. The overall survival was much longer than in previously reported cases. Correct diagnosis with early aggressive treatment may have benefits for prognosis.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Cadranel J, Wislez M, Antoine M. Primary pulmonary lymphoma. Eur Respir J 2002; 20: 750–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kurtin PJ, Myers JL, Adlakha H et al Pathologic and clinical features of primary pulmonary extranodal marginal zone B‐cell lymphoma of MALT type. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 25: 997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li G, Hansmann ML, Zwingers T, Lennert K. Primary lymphomas of the lung: Morphological, immunohistochemical and clinical features. Histopathology 1990; 16: 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mizuki M, Ueda S, Tagawa S et al Natural killer cell‐derived large granular lymphocyte lymphoma of lung developed in a patient with hypersensitivity to mosquito bites and reactivated Epstein‐Barr virus infection. Am J Hematol 1998; 59: 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oshima K, Tanino Y, Sato S et al Primary pulmonary extranodal natural killer/T‐cell lymphoma: Nasal type with multiple nodules. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: 795–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee BH, Kim SY, Kim MY et al CT of nasal‐type T/NK cell lymphoma in the lung. J Thorac Imaging 2006; 21: 37–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laohaburanakit P, Hardin KA. NK/T cell lymphoma of the lung: A case report and review of literature. Thorax 2006; 61: 267–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xiao YL, Zhang DP, Wang Y. [Primary pulmonary involvement of NK/T cell lymphoma: Report of two cases with literature review.] Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2007; 46: 988–991. (In Chinese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu CH, Wang HH, Perng CL et al Primary extranodal NK/T‐cell lymphoma of the lung: Mimicking bronchogenic carcinoma. Thoracic Cancer 2014; 5: 93–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chan JK. Natural killer cell neoplasms. Anat Pathol 1998; 3: 77–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liao JB, Chuang SS, Chen HC, Tseng HH, Wang JS, Hseih PP. Clinicopathologic analysis of cutaneous lymphoma in Taiwan: A high frequency of extranodal natural killer/T‐cell lymphoma, nasal type, with an extremely poor prognosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010; 134: 996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bouafia F, Drai J, Bienvenu J et al Profiles and prognostic values of serum LDH isoenzymes in patients with haematopoietic malignancies. Bull Cancer 2004; 91: E229–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guinee D Jr, Jaffe E, Kingma D et al Pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Evidence for a proliferation of Epstein‐Barr virus infected B‐lymphocytes with a prominent T‐cell component and vasculitis. Am J Surg Pathol 1994; 18: 753–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kwong YL, Kim WS, Lim ST et al SMILE for natural killer/T‐cell lymphoma: Analysis of safety and efficacy from the Asia Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 2012; 120: 2973–2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]