Abstract

Mutations in the gene encoding subunit B of the mitochondrial enzyme succinate dehydrogenase (SDHB) are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and are associated with hereditary paraganglioma (PGL) and pheochromocytoma. The phenotype of patients with SDHB point mutations has been previously described. However, the phenotype and penetrance of gross SDHB deletions have not been well characterized as they are rarely described. The objective was to describe the phenotype and estimate the penetrance of an exon 1 large SDHB deletion in one kindred. A retrospective and prospective study of 41 relatives across five generations was carried out. The main outcome measures were genetic testing, clinical presentations, plasma catecholamines and their O-methylated metabolites. Of the 41 mutation carriers identified, 11 were diagnosed with PGL, 12 were found to be healthy carriers after evaluation, and 18 were reportedly healthy based on family history accounts. The penetrance of PGL related to the exon 1 large SDHB deletion in this family was estimated to be 35% by age 40. Variable expressivity of the phenotype associated with a large exon 1 SDHB deletion was observed, including low penetrance, diverse primary PGL tumor locations, and malignant potential.

Keywords: paraganglioma, penetrance, pheochromocytoma, SDHB deletion, succinate dehydrogenase subunit B

Paragangliomas (PGLs) are neuroendocrine tumors that originate from neural crest cells in the adrenal medulla or along the sympathetic and parasympathetic ganglia. Pheochromocytoma (PHEO) specifically refers to the adrenal presentation of these tumors. Various point mutations in the gene encoding subunit B of the mitochondrial enzyme succinate dehydrogenase (SDHB) have been identified and shown to cause predominantly norepinephrine (NE)-producing PGL originating in adrenal, head and neck, and extra-adrenal abdominal locations (1–5). Extra-adrenal abdominal PGLs associated with SDHB point mutations have a high metastatic potential (1, 6–8) and a poor prognosis (9). However, the phenotype associated with large SDHB deletions is not well known as these mutations are rare and missed by standard direct sequencing methods (3, 6, 10). Recently, easier to implement methods employing multiplex amplification have been developed to detect large SDHB deletions (9, 11).

To date, eight families have been found to carry large deletions of exon 1, suggesting a probable recombination hot spot region (9, 11–13). The first three families identified with this exon 1 mutation originated from Brazil, Portugal, and Spain (11, 12). Recently, two new families originated from a similar region in the Iberian Peninsula as the previously reported Spanish patients were also identified as having the same exon 1 deletion breaking points (15.69 kb), suggesting a founder mutation (13). Three other families of French descent have also been affected by this large exon 1 SDHB deletion (9, 13). Of the 14 affected relatives identified from these eight families, 9 developed extra-adrenal abdominal PGL, 1 carotid body PGL, 1 thoracic PGL, 2 adrenal PHEO, and 1 possibly SDHB-related metastatic neuroblastoma. Only two other cases have been attributed to large SDHB deletions spanning different regions of the gene, one with a deletion of exons 3–8 (9) and another with an entire deletion of the SDHB gene (11). Limited information on the phenotype of patients with large SDHB deletions exists due to the small number of patients identified to date.

In this study, we describe the phenotype of 41 relatives of Spanish-Mexican descent found to have the same founder exon 1 SDHB heterozygous deletion previously reported in the literature for patients from the Iberian Peninsula. We discuss in detail the diverse clinical and biochemical phenotype of 11 relatives with PGL/PHEO and provide a Kaplan–Meier estimate of the penetrance of the gross deletion in this family.

Materials and methods

Patients

In 2002, a genetically determined form of PGL was suspected in the 41-year-old proband, IV-1, due to her family history of PGL and metastatic disease, 9 years after excision of a 10-cm left adrenal PHEO. Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a recurrence in the left adrenal bed of 4.5 cm, two metastatic liver lesions (the largest being 7 cm), and bone lesions in the lumbar spine. Her biochemical evaluation showed elevated plasma NE levels of 11,350 (80–498 pg/ml) and normetanephrine levels of 7304 (18–112 pg/ml). During this visit, she was accompanied by her younger sister, IV-11, with a medical history of pelvic PGL. No genetic mutations were detected after direct sequencing of the succinate dehydrogenase (SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD), von Hippel-Lindau (VHL), and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (RET) genes. However, we still had a high clinical suspicion for an SDHB mutation due to the proband's malignant phenotype and family history of PGL. In the hypothesis of a large SDHB deletion not detectable by direct sequencing, both sisters were tested with the quantitative multiplex polymerase chain reaction of short fluorescent fragments (QMPSF) method.

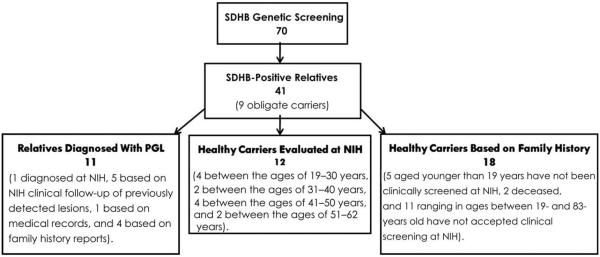

Subsequently, clinical and family history information was obtained on 40 of the proband's relatives, defined as those sharing a common ancestor across five generations (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study demographics. PGL, paraganglioma; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with and approval by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using standard methods (GENTRA Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). Direct sequencing for point mutations in the SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, VHL, and RET genes was performed in IV-1 and IV-11 as previously described (14). The QMPSF method was employed to screen for large rearrangements of the SDHB gene. The eight coding exons of the SDHB gene were amplified in one multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR). An additional fragment, from the HMBS gene, was co-amplified as a control in each PCR. The size of the fragments ranged from 208 to 341 bp. A 5′ extension, consisting of a rare combination of 10 nucleotides preceding the exon-specific sequence, was added to the primers as previously described (15). The forward primer of each pair was 5′ end labeled with 6-FAM fluorochrome. After amplified DNA fragments were separated using an ABI PRISM 3730 DNA Analyzer sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), data were analyzed using the genemapper software version 4.0 (Applied Biosystems).

Deletion breaking points

To establish the deletion break points occurring in these patients with germ line exon 1 SDHB deletion, we performed a PCR amplification specific of the Iberian Peninsula founder deletion (13).

We designed a pair of primers flanking the break points of the 15.69-kb deletion previously described.

Forward primer: GTAAAATAGATACGAGCCATCACTGG

Reverse primer: TAGTAGGGTAAGTGGGACAATATGCC

The amplification of a 228-bp fragment with this pair of primers is specific of the presence of the 15.69-kb heterozygous deletion.

Evaluation of phenotype

Medical records were requested from relatives with a previous diagnosis of PHEO/PGL at outside institutions and invited for clinical screening at NIH. In addition, carriers identified through mutation testing were invited to the NIH for appropriate screening. Family history reports from close relatives described the health status, age of diagnosis, and symptoms of relatives who were not available for clinical screening.

Clinical screening at NIH consisted of examination by standardized inventory of symptoms and signs as previously described (16). Radiological tumor screening at NIH included a whole-body CT of the head/neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis (CT scans were performed using a GenesisHi-Speed scanner; General Electric Healthcare Technologies, Waukesha, WI). Section thickness was up to 3 mm in the neck, 5 mm through the chest and abdomen, and 7.5 mm through the pelvis. Most studies were performed with a rapid infusion of non-ionic water-soluble contrast agent and oral barium contrast.

Loss of heterozygosity studies of non-PGL tumors

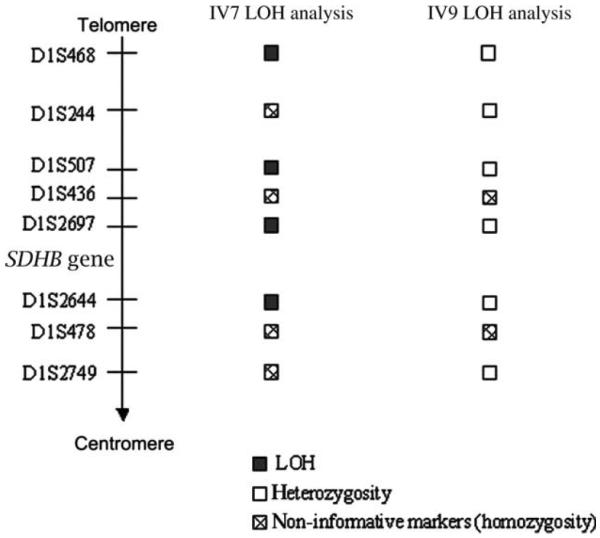

DNA was extracted from frozen tissue using standard techniques (GENTRA Systems, Inc.). Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) studies were performed as previously described (8). LOH analysis was performed for tumoral and germ line DNA samples using eight fluorescent microsatellite markers (D1S468, D1S244, D1S507, D1S436, D1S2697, D1S2644, D1S478, and D1S2749) overlapping a 50-cM region between telomere and 1p35, including SDHB locus.

Kaplan–Meier analysis

Penetrance of the gross exon 1 SDHB deletion in this family was estimated by cumulative incidence functions using Kaplan–Meier analysis where survival time was substituted by age at diagnosis (17). Only 23 of the 41 relatives identified as carriers were used for the analysis as the 18 relatives who have not been clinically evaluated at NIH may have an asymptomatic PHEO/PGL.

Results

Germ line exon 1 SDHB deletion

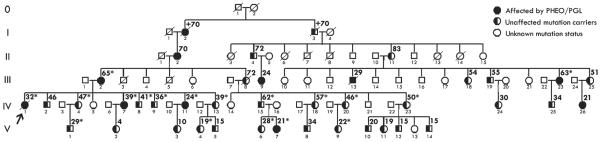

A five-generation pedigree is given in Fig. 2. Proband IV-1 and 40 additional relatives were identified as carriers of a large heterozygous exon 1 deletion of the SDHB gene. Nine relatives were identified as obligate carriers, based on their diagnosis of PGL or evidence of transmission of SDHB-related PGL to their offspring, and a gross deletion was identified in 31 relatives with the QMPSF method as shown by the twofold reduction of the corresponding exon 1 peak in the representative result in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Abbreviated pedigree of the large family with the gross SDHB exon 1 deletion, focusing on the 41 known mutation carriers. Individuals have Arabic numbers within each generation I–V. The age at presentation with PGL/PHEO and current age of unaffected mutation carriers are found at the upper right-hand corner of the symbol. An asterisk next to the age denotes those individuals clinically evaluated at NIH. The proband is designated with an arrow. PGL, paraganglioma; PHEO, pheochromocytoma.

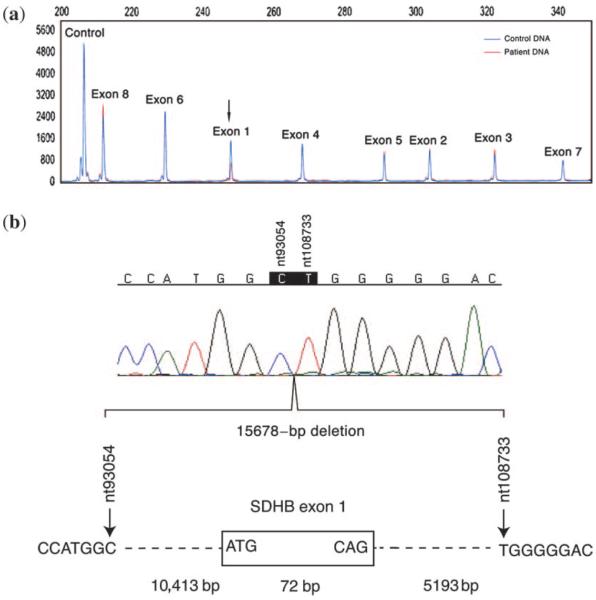

Fig. 3.

Identification of SDHB exon 1 deletion with quantitative multiplex polymerase chain reaction of short fluorescent fragments and determination of deletion breaking points by direct sequencing. (a) Large deletion of the first exon revealed by a twofold reduction of the corresponding peak obtained for the patient IV-1 DNA (red) comparing with a control subject (blue) after adjustment of the two peaks obtained with the control polymerase chain reaction (HMBS amplicon) to the same peak height. (b) Direct sequencing of the 228-bp fragment showing the SDHB exon 1 deletion break points in this family. This 15,678-bp deletion is the deletion previously described as Iberian Peninsula founder mutation. The nucleotides numeration is based on the NCBI reference sequence AL049569.

Determination of the deletion breaking points using PCR analysis revealed an identical deletion to the previously cited Iberian Peninsula founder mutation (11, 13) (Fig. 3).

Clinical presentations of PGL

Eleven mutation carriers were diagnosed with PGL in various locations, including 6 in the carotid body, 3 in the adrenal gland, 1 in the pelvis, and 1 in the thorax. The clinical presentation of the 41 mutation carriers is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Phenotype of 41 SDHB deletion carriers in one kindred

| Subject | Sex | Age at follow-up | Type of evaluation | Age at PGL diagnosis | Exon 1 SDHB deletion | PGL location | Prim. PGL size (cm) | Elevated biochemistry at diagnosis | Elevated biochemistry at follow-up | Disease course | Other tumor (age at diagnosis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V-4 | F | 19 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | Negative clinical screening |

| IV-26 | F | 22 | Pathology report |

21 | Confirmed | Mediastinum | 8 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | None reported |

| V-9 | F | 22 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | Negative clinical screening |

| V-6 | F | 28 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | None reported |

| V-1 | M | 29 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | None reported |

| V-7 | F | 31 | NIH visit | 21 | Confirmed | RT carotid body |

2.2 | Normal | Normal | Benign | None reported |

| IV-11 | F | 33 | NIH visit | 24 | Confirmed | Pelvis | 7 | Elevated | Normal | Benign | Negative clinical screening |

| III-13 | M | 33b | Family history |

29 | Obligatory | LT adrenal gland |

Unknown | Elevated | n/a | Malignant (33) | Negative clinical screening |

| IV-9 | M | 36 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | Papillary thyroid cancer (36) |

| IV-13 | F | 39 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | Uterine lelomyomas |

| III-9 | F | 40 | Family history |

24 | Obligatory | Adrenal | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Negative clinical screening |

| IV-8 | M | 41 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | None reported |

| IV-7 | F | 42 | NIH visit | 39 | Confirmed | RT carotid gland |

6 | NE and NMN | Normal | Benign | Renal cell carcinoma/oncocytoma (42) |

| IV-20 | F | 46 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | Negative clinical screening |

| IV-4 | F | 47 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | Adrenal nodule (1 cm) |

| IV-1 | F | 48b | NIH visit | 32 | Confirmed | LT adrenal gland |

10 | NE and NMN | NE and NMN | Malignant (41) | Negative clinical screening |

| IV-23 | F | 50 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | None reported |

| IV-18 | F | 57 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | Negative clinical screening |

| IV-15 | M | 62 | NIH visit | n/a | Confirmed | Negative clinical screening |

n/a | n/a | Normal | n/a | Papillary bladder cancer (59) |

| III-23 | F | 63 | NIH visit | 63 | Confirmed | RT carotid body |

2.1 | Normal | n/a | Benign | Uterine adenocarcinoma (62) |

| III-2 | F | 75 | NIH visit | 65 | Confirmed | RT carotid body |

4 | Normal | Normal | Recurrence (75) | Basocellular carcinoma precordial (74) |

| I-2 | F | 90 | Family history |

70+ | Obligatory | Carotid body |

Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | None reported |

| II-2 | F | 93 | Family history |

70 | Obligatory | RT carotid body |

Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | None reported |

| V-2 | F | 4 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| V-3 | F | 10 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| V-5 | M | 15 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| V-12 | M | 15 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| V-14 | M | 15 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| V-11 | F | 19 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| V-10 | M | 20 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| IV-24 | F | 30 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| IV-25 | M | 34 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| V-8 | M | 34 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| IV-2 | M | 46 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| III-25 | F | 51 | Family history |

n/a | Obligatory | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| III-18 | F | 54 | Family history |

n/a | Confirmed | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| III-19 | M | 55 | Family history |

n/a | Obligatory | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| II-4 | M | 72 | Family history |

n/a | Obligatory | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| II-11 | F | 83 | Family history |

n/a | Obligatory | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | None reported |

| I-3 | M | 70+b | Family history |

n/a | Obligatory | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Unknown |

| III-8 | F | 72b | Family history |

n/a | Obligatory | None reported |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | lung cancer (72) |

CA, cancer; LT, left; met, metastatic; n/a, not applicable; NE, norepinephrine; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NMN, normetanephrine; PGL, paraganglioma; PHEO, pheochromocytoma; RT, right.

The 23 subjects highlighted in gray either have a family history of PGL or are currently healthy carriers as determined by a clinical evaluation at NIH. Only family history information is available for the remaining 18 subjects as they have not been evaluated at NIH.

Age deceased.

Non-PGL malignancies

Table 1 summarizes other non-PGL malignancies detected in SDHB deletion carriers in this family. At age 42, 3 years after being diagnosed with a carotid body PGL, the proband's sister (IV-7) was diagnosed with a 2-cm hybrid renal cell carcinoma chromophobe/oncocytoma tumor. Similarly, the proband's younger brother (IV-9) was diagnosed with papillary thyroid cancer (2-cm solitary nodule in the left thyroid lobe) at age 36. LOH analysis was performed on these two non-PGL tumors. We have detected LOH in the 1pter to 1p35 in IV-7's hybrid renal cell carcinoma chromophobe/oncocytoma tumor but not in IV-9's papillary thyroid cancer (Fig. 4). Other malignancies observed in mutation carriers included papillary bladder cancer (IV-9), uterine adenocarcinoma (III-23), and lung cancer (III-8) (Table 1). Tumor tissue was not available for genetic analysis.

Fig. 4.

Somatic LOH analysis of eight microsatellite markers at chromosome 1pter to 1p35 for IV-7 and IV-9 tumors. LOH, loss of heterozygosity.

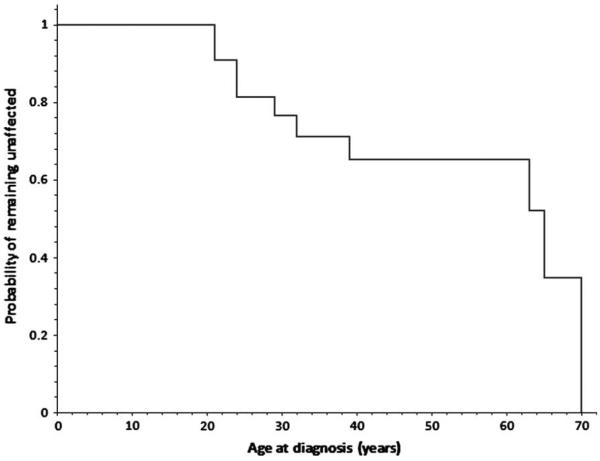

Kaplan–Meier estimates of penetrance

A Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to estimate the penetrance of the gross exon 1 SDHB deletion in this family as a function of the age of diagnosis (Fig. 5). The penetrance of this mutation is estimated to be 23% by age 30 and 35% by age 40.

Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier analysis curve displaying the probability of 23 exon 1 SDHB mutation carriers from the same family of remaining unaffected from birth to the age of 70 years.

Discussion

The present study describes the phenotype associated with a previously described founder SDHB exon 1 deletion. A high variability in the PGL tumor sites – including a possibly SDHB-related hybrid renal cell carcinoma chromophobe/oncocytoma tumor – diverse biochemical profiles, and disease courses (both malignant and benign) were observed in this family. Our findings not only emphasize the importance of ruling out the presence of large SDHB deletions in patients with familial PGL but also have implications for the clinical management of these patients, including appropriate preventive measures and genetic counseling.

Phenotype of SDHB mutations vs gross deletions

Although the small number of reported SDHB deletion cases prevents any definite comparisons between the phenotypes of point SDHB mutation carriers and the large deletion carriers, the 11 relatives with PGL from this large family suggest a similar phenotype.

Previous studies of the clinical phenotype of SDHB point mutation carriers have shown a predisposition for head and neck, thoracic, and extra-adrenal abdominal PGL (18, 19). Similarly, SDHB deletion cases reported in the literature have presented with PGL in all these locations. Although the majority of SDHB deletion cases published (10 of 14) had extra-adrenal abdominal PGL (11–13), our family screening study found a large number of cases with carotid and adrenal PHEO as well.

The more favorable prognosis of affected SDHB deletion carriers in this family, compared with other patients with SDHB point mutations, may be due to the fact that most of the primary tumors detected in this family arose from the head/neck area. Head and neck PGL are usually symptomatic and can be rapidly diagnosed and operated on, whereas thoracic and abdominal PGL may go undetected for a long period of time and diagnosed lately after the occurrence of first metastasis (6, 7, 20).

Non-PGL malignancies in SDHB deletion carriers

Previous reports detected cases of renal cell cancer caused by point mutations in the SDHB gene, suggesting that <3% of renal cancers may be due to an SDHB mutation (21–23). Herein, we present the first report of LOH study of chromosome 1p from a renal hybrid tumor. Our findings reveal a possible association between this hybrid renal tumor and SDHB-related PGL. Further screening of relatives of SDHB mutation carriers is needed to ascertain the prevalence of renal cancer in this family.

Papillary thyroid cancer is another malignancy that was also previously discussed in the literature to possibly be a component of SDHB-related PGL (19). However, tumor DNA analysis of the papillary thyroid cancer tumor DNA in this study did not show LOH of the chromosome 1p. Previous studies examining the 1p chromosomal region in thyroid cancer found LOH in the 1p chromosome in thyroid adenoma and medullary carcinoma but not in papillary carcinoma (24). Our data suggest that papillary thyroid cancer is not a component of the SDHB-related hereditary PGL.

Other malignancies observed in SDHB mutation carriers in this family included papillary bladder cancer, uterine adenocarcinoma, and lung cancer. None of these tumors are currently suspected to be associated with SDHB, but tumor tissue was not available to rule out possible connections.

Estimated penetrance

There are only eight families affected by large exon 1 SDHB deletion reported in the literature to date; therefore, calculating the penetrance is at this time inappropriate due to bias of ascertainment and the small number of clinically unaffected mutation carriers investigated. Although only 23 of 41 mutation carriers in this family were available for penetrance estimates, our study suggests a slightly lower penetrance by age 40 than previously cited in the literature for SDHB point mutation carriers. In a previous study of 82 SDHB point mutation carriers, an estimated 45% developed PGL by age 40 (18). In our report, with a smaller number of subjects, the penetrance of PGL related to exon 1 large SDHB deletion based on a Kaplan–Meier analysis was slightly lower and estimated to be 35% by age 40.

Conclusions

SDHB large deletion testing should be considered in patients with familial PGL who lack evidence of point mutations of susceptibility genes. The clinical spectrum among large SDHB deletion carriers appears to be similar to SDHB point mutation carriers with the exception of a slightly lower penetrance. Large SDHB deletions may also predispose to non-PGL tumors, such as hybrid renal cell carcinoma chromophobe/oncocytomas.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of this large family for participating in our study. We thank Dr P. Saugier-Veber, Prof M. Tosi and Prof T. Frébourg (INSERM U614, IFRMP, Faculty of Medicine, Rouen, France) for their advice on adapting the QMPSF technology to search for large rearrangements of PGL susceptibility genes. We also thank Thanh Truc Huynh (Reproductive and Adult Endocrinology Program, NICHD, NIH) for technical support in this project.

Funding This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NICHD/NIH.

References

- 1.Gimenez-Roqueplo A, Favier J, Rustin P, et al. Mutations in the SDHB gene are associated with extra-adrenal and/or malignant phaeochromocytomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5615–5621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astuti D, Hart-Holden N, Latif F, et al. Genetic analysis of mitochondrial complex II subunits SDHD, SDHB and SDHC in paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma susceptibility. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;59:728–733. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baysal B, Willett-Brozick J, Lawrence E, et al. Prevalence of SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD germline mutations in clinic patients with head and neck paragangliomas. J Med Genet. 2002;39:178–183. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.3.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benn D, Croxson M, Tucker K, et al. Novel succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) mutations in familial phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas, but an absence of somatic SDHB mutations in sporadic phaeochromocytomas. Oncogene. 2003;22:1358–1364. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin T, Irving R, Maher E. The genetics of paragangliomas: a review. Clin Otolaryngol. 2007;32:7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2007.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Astuti D, Latif F, Dallol A, et al. Gene mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase subunit SDHB cause susceptibility to familial pheochromocytoma and to familial paraganglioma. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:49–54. doi: 10.1086/321282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brouwers F, Eisenhofer G, Tao J, et al. High frequency of SDHB germline mutations in patients with malignant catecholamine-producing paragangliomas: implications for genetic testing. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4505–4509. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gimenez-Roqueplo A, Favier J, Rustin P, et al. Functional consequences of a SDHB gene mutation in an apparently sporadic pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4771–4774. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amar L, Baudin E, Burnichon N, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase B gene mutations predict survival in patients with malignant pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3822–3828. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armour J, Barton D, Cockburn D, et al. The detection of large deletions or duplications in genomic DNA. Hum Mutat. 2002;20:325–337. doi: 10.1002/humu.10133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cascón A, Montero-Conde C, Ruiz-Llorente S, et al. Gross SDHB deletions in patients with paraganglioma detected by multiplex PCR: a possible hot spot? Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:213–219. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McWhinney S, Pilarski R, Forrester S, et al. Large germline deletions of mitochondrial complex II subunits SDHB and SDHD in hereditary paraganglioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5694–5699. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cascón A, Landa I, López-Jiménez E, et al. Molecular characterisation of a common SDHB deletion in paraganglioma patients. J Med Genet. 2008;45:233–238. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.054965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amar L, Bertherat J, Baudin E, et al. Genetic testing in pheochromocytoma or functional paraganglioma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8812–8818. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houdayer C, Gauthier-Villars M, Laugé A, et al. Comprehensive screening for constitutional RB1 mutations by DHPLC and QMPSF. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:193–202. doi: 10.1002/humu.10303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timmers H, Kozupa A, Eisenhofer G, et al. Clinical presentations, biochemical phenotypes, and genotype-phenotype correlations in patients with succinate dehydrogenase subunit B-associated pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:779–786. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benn D, Gimenez-Roqueplo A, Reilly J, et al. Clinical presentation and penetrance of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma syndromes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:827–836. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann H, Pawlu C, Peczkowska M, et al. Distinct clinical features of paraganglioma syndromes associated with SDHB and SDHD gene mutations. JAMA. 2004;292:943–951. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amar L, Servais A, Gimenez-Roqueplo A, et al. Year of diagnosis, features at presentation, and risk of recurrence in patients with pheochromocytoma or secreting paraganglioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2110–2116. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricketts C, Woodward E, Killick P, et al. Germline SDHB mutations and familial renal cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1260–1262. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srirangalingam U, Walker L, Khoo B, et al. Clinical manifestations of familial paraganglioma and phaeochromocytomas in succinate dehydrogenase B (SDH-B) gene mutation carriers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69:587–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanharanta S, Buchta M, McWhinney S, et al. Early-onset renal cell carcinoma as a novel extraparaganglial component of SDHB-associated heritable paraganglioma. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:153–159. doi: 10.1086/381054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubo K, Yoshimoto K, Yokogoshi Y, et al. Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 1p in thyroid adenoma and medullary carcinoma, but not in papillary carcinoma. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1991;82:1097–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1991.tb01763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]