Abstract

Study Design.

A case report.

Objective.

To report a case of the lumbar giant cell tumor (GCT) utilizing a new clinical treatment modality (denosumab therapy), which showed a massive tumor reduction combined with the L4 spondylectomy.

Summary of Background Data.

There are some controversies about spinal GCT treatments. Denosumab has provided good clinical results in terms of tumor shrinkage, and local control in a short-time follow-up clinical study phase 2, although for spinal lesions, it has not been described. Nonetheless, “en bloc” spondylectomy has been accepted as being the best treatments modalities in terms of oncological control.

Methods.

A case study with follow-up examination and series radiological assessments 6 months after therapy started, followed by a complex spine surgery.

Results.

The denosumab therapy showed on the lumbar computed tomography scans follow-up 6 months later, a marked tumor regression around 90% associated to vertebral body calcification, facilitating a successful L4 spondylectomy with an anterior and posterior reconstruction. The patient recovered without neurological deficits.

Conclusion.

A new therapeutic modality for spinal GCT is available and showing striking clinical results; however, it is necessary for well-designed studies to answer the real role of denosumab therapy avoiding or facilitating complex spine surgeries as spondylectomies for spinal GCT.

Level of Evidence: 5

Keywords: arthrodesis, discectomy, laminectomy, lumbar pain, neuromonitoring, radiotherapy, spinal instability, spondylectomy, transperitoneal approach, vertebral giant cell tumor

Giant cells tumor (GCT) is a rare aggressive benign spinal neoplasm with an unpredictable behavior.1 GCT usually occurs at the end of long bones.2 Only 2% to 3% of the cases occur in the spine and sacrum, having a slight preponderance of females to males (1.5: 1).3 Histologically, GCT of the bone consists of neoplastic mononuclear cells (stromal cells) with an osteoclast-like giant cell. These cells express RANK ligand, which is a pivotal mediator of osteoclast formation, function, and survival.4,5 Osteoclasts activation plays a crucial event in the development and progression of this disease.

The optimal treatment of GCT is controversial. Over the last two decades, the surgical resection, preferentially “en bloc” spondylectomy has shown the best results.6,7 When compared with other spinal GCT treatment modalities, such as a piecemeal resection, radiotherapy, and embolization, it showed lower local recurrence rates, in spite of morbidity and became, under oncological perspective, the first option for the best local oncological control. On the other hand, radiotherapy is reserved for residual, inoperable lesions, or for patients without any clinical conditions to undergo a major surgical procedure8 showing a good local control. Nevertheless, it presents a potential risk of the malignant transformation. Recently, the denosumab, which is a fully human monoclonal antibody that specifically inhibits RANKL,9 thereby inhibiting osteoclast activation, has provided good clinical results in terms of tumor shrinkage, and local control in a short time follow-up.10 Herein, the aim of the authors was to report to the best of their knowledge the first case of a patient with spinal GCT that was managed with combined fourth lumbar spondylectomy and denosumab therapy.

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old male was referred to our Oncological Spinal Center to evaluate a severe back pain associated with a L4 nerve root pain and complete motor deficit during the last 48 hours. His history started 2 months before his admission, with progressive back pain irradiated to the L4 dermatome on the right side. He did not present any history of fever, loss of weight, trauma, and previous infection. His physical examination showed a tender point on the back, an absence of patellar jerk on the right leg, loss of strength of the leg extension, and dorsiflexion of the right foot. Laboratory examinations were normal for infection, hematological diseases, and parathyroid disease. The X-ray plan was normal; however, the spine computed tomography (CT) scan evidenced an osteolytic lesion involving the L4 vertebral body without any instability, and the lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed the L4 vertebral body involvement with the right paravertebral extension toward the psoas muscle, the transverse process and pedicle on the T1 contrast MRI (Figure 1) with compression of the right L4/L5 nerve roots. No evidence of another spinal involvement was found. Surgery was immediately carried out to decompress the L4/L5 nerve roots on the right side, and make an arthrodesis to achieve the diagnosis, and to obviate spinal instability. After pathological and immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2), the diagnostic of the GCT was done. The patient improved his deficit 1 month later. A preoperatively MRI showed an intact anterior tumor lesion (Enneking SIII) (Figure 3). Based on a clinical study phase 2, we prescribed him six cycles of the 120 mg denosumab subcutaneously monthly, with a daily ingestion of the 400 IU vitamin D and 1 g calcium. No adverse effects were observed. During the treatment, the lumbar CT scan imaging series showed a massive reduction of the paravertebral volume (>90%) associated with a vertebral body calcification (Figure 4). The patient was scheduled for an anterior L4 spondylectomy after six cycles of the denosumab treatment. Based on Tomita technique, in two stages (first part: posterior approach; second part: anterior approach), under spinal cord neuromonitoring through the somatosensory-evoked potentials (SSEPs) and motor evoked potentials (MEPs), these two stages took 12 hours to be completed. During the first part, we bilaterally released the L3 and L4 nerve roots, anterior release of Hoffman's ligaments to the dura mater, discectomies as lateral as possible, and utilizing a Bone Scalpel (SONOCA 300, Soering GmbH, Germany) to take out the left transverse process, pars interarticularis, superior facet, and pedicle en bloc, and replaced the pedicle screws two levels above and below the L4. The second part was completed by an anterior transperitoneal approach (Figure 5) by an oncological surgeon exposing the aorta and the inferior vena cava. The vertebral body was taken out after complete discectomies L3-L4 and L4-L5 and the psoas muscle were released bilaterally from the L4 vertebral body with no uneventful events (Figure 6), after an anterior reconstruction utilizing an expandable cage and anterior plate (Figure 7). A new histological analysis was performed (Figure 8). After 24 hours in the intensive care unit, the patient was discharged from the hospital on the fourth postoperative day, being able to walk without any neurological deficit.

Figure 1.

The magnetic resonance imaging T1 contrast sequence. The L4 lesion presents a high intense contrast enhancement in the vertebral body with extension to the right pedicle and transverse process; expansion of mass forming a pseudocapsule (Enneking SIII).

Figure 2.

Multinucleate giant cells are seen surrounded by neoplastic stromal cells: pre-denosumab therapy (hematoxylin and eosin 40×).

Figure 3.

Postoperative lumbar computed tomography scan after the first surgery and before starting the denosumab therapy.

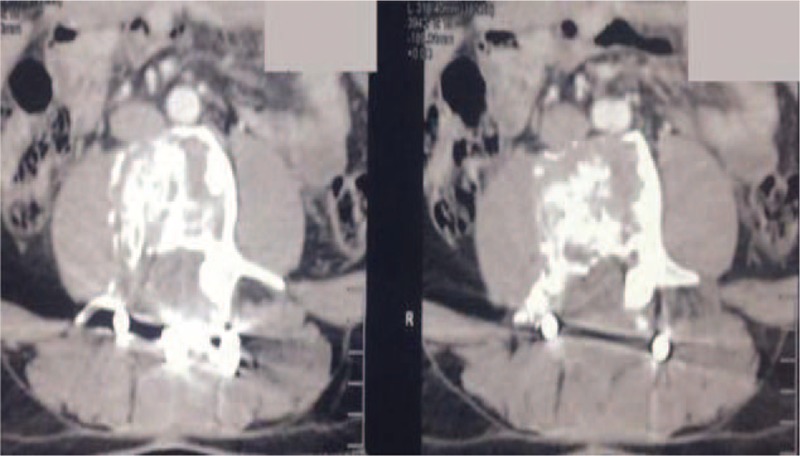

Figure 4.

After 6 months of the denosumab therapy, showing a reduction of the volume tumor, more than 90% associated with calcification.

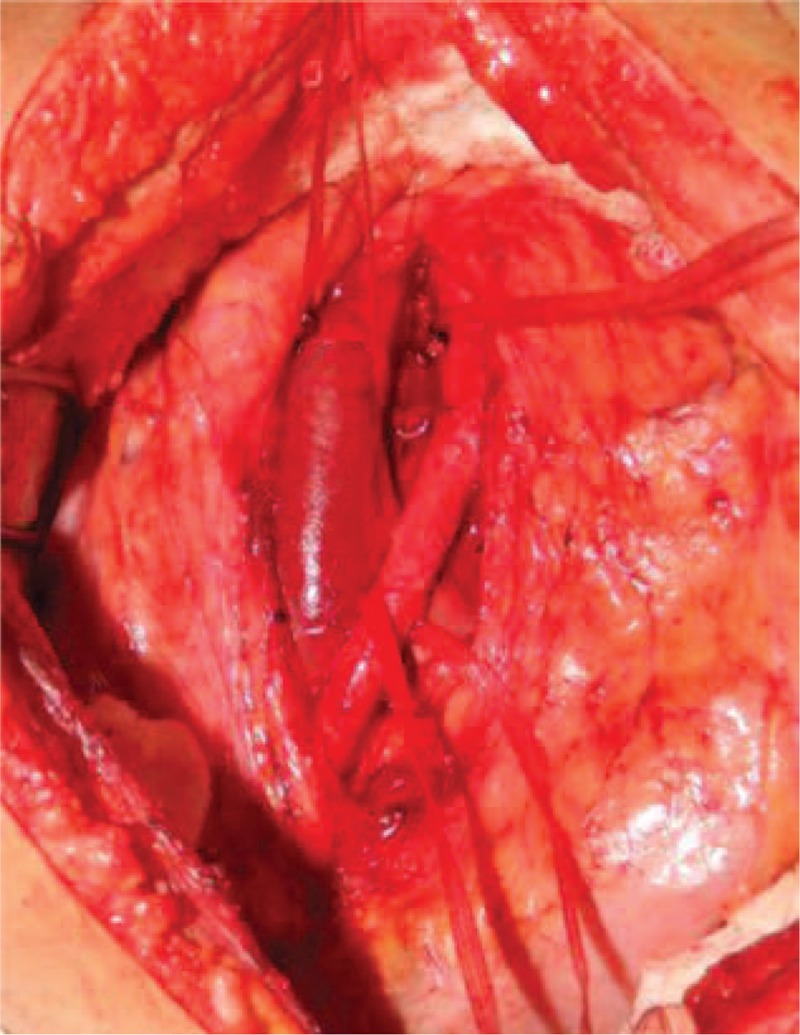

Figure 5.

Showing an exposure via transperitoneal approach of the inferior vena cava and aorta bifurcation over L4 vertebral body.

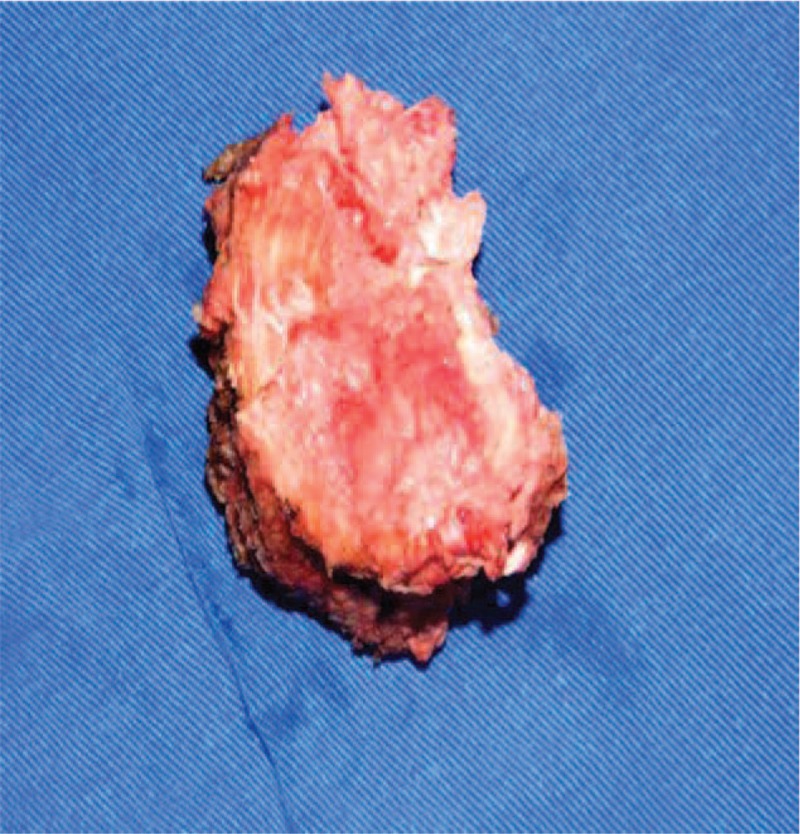

Figure 6.

A complete removal of the L4 vertebral body was completed by anterior transperitoneal approach.

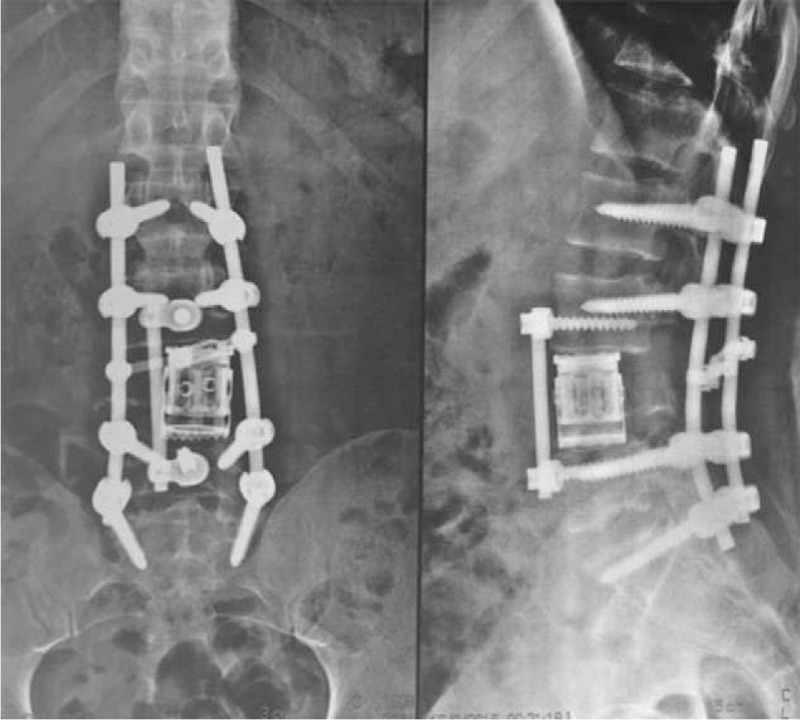

Figure 7.

X-ray images are showing an anterior and posterior reconstruction, using expandable cage anteriorly and fixation with pedicle screws two levels above and below.

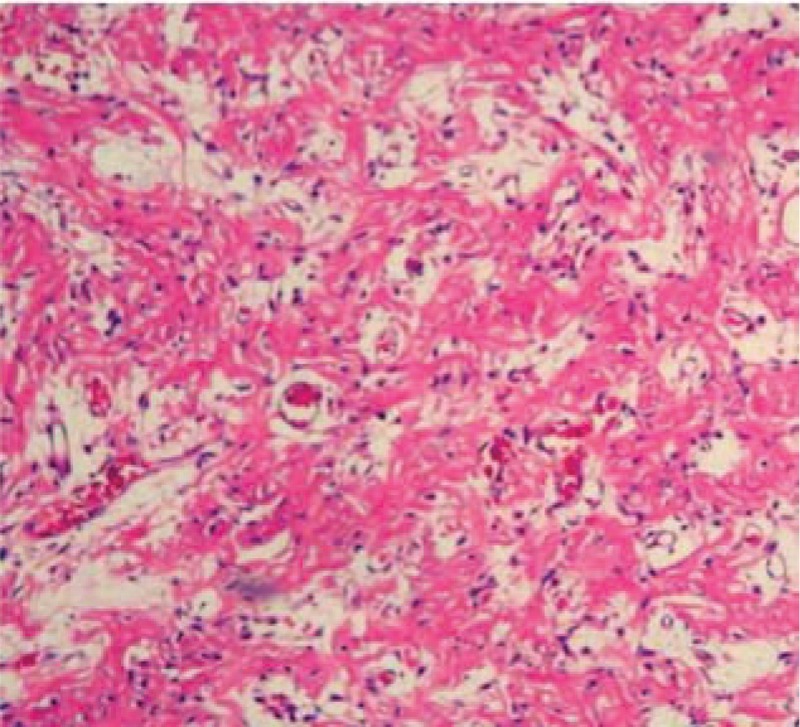

Figure 8.

Demonstrates an absence of giant cells and stromal cells inside of the L4 vertebral body after spondylectomy and 6 months of the denosumab therapy (hematoxylin and eosin 40×).

DISCUSSION

Spinal GCT is a rare entity accounting for less than 2% to 3% of all bone GCT,11 and its treatment is still challenging. The literature has not yet provided a consensus between oncological spinal surgeons; what is the best approach to manage it and certainly it should be based on age, site, neurological status, and feasibility of the en bloc resection, presence of metastases, rates of recurrence, comorbidities, and local stage. At present, surgical resection of the lesion with wide or marginal margins has been accepted as being the best treatment12 to achieve good oncological control, minimizing the risk of local recurrence, and obviating high comorbidities associated with reoperations;12,13 however, a criticism of this procedure is the morbidity associated with it,13 and the fact that this should be considered and discussed with patient beforehand. An intralesional excision with adjuvant treatment is also an option treatment, which provides a good functional neurological results in relation to installed deficit but its high recurrence rates, ranging from 36% to 49%,14 could create a necessity of reoperation and radiotherapy treatment after incomplete resection, making this approach less suitable in some cases like ours.12 This more conservative approach should be out weighted mainly for sacral GCT, presenting an acceptable local recurrence rate of 29.2% at 13-month follow-up, and 5-year local recurrence free survival rate of 69.6%.15 For sacral GCT, an intralesional excision obviates the neurological deficit associated with en bloc sacrectomy, improving the patient's quality of life. In an emergence context, such as acute neurological deficit without previous biopsy, this approach was acceptable to decompress nerve roots and to restore neurological function, which occurred 1 month later in our case. An arthrodesis was performed to achieve a spinal fusion and prevent a deformity development and chronic lumbar pain, after a wide bilaterally laminectomy. The intraoperatively pathological analysis suggested GCT tumor, and it was confirmed after immunohistochemical study. After the GCT diagnosis was made and patient's neurological recovered, three options were pointed out: radiotherapy, en bloc spondylectomy, and denosumab therapy. Initially, the first was discarded because we have a young patient, without comorbidities, and the 11% risk of sarcoma transformation16 should be raised despite the high local control of 84%.8 This option should be considered, when a trade-off between surgical risks and patient cure is desirable. En bloc spondylectomy is an amenable alternative for lumbar spine without significant neurological risks and mortality associated.17,18 As described by Boriani et al,19 patients who have Weinstein-Boriani-Biagini 5–8, 4–9 zones, Enneking S3 (aggressive stage for benign spine tumors) are the best candidates for this approach. In our case, we did not have this condition preoperatively because the right pedicle was violated. This suitable approach demands a complete surgical oncological team with spine, oncological, and vascular surgeons involved to accomplish a safe procedure to minimize contamination, thus potentially decreasing the likelihood of local recurrence. Based on a clinical study phase 2,10 which showed 86% regression of bone GCT after 6 months of denosumab therapy, we decided to start the same scheme therapy in our patient. An impressive regression of the lesion on the follow-up lumbar spine CT scan (about 90%), in addition to paravertebral calcification was noted. Then, the authors decided to perform a major surgery due to regression of the lesion and additional calcification in an attempt to minimize a local recurrence after drug cessation.20 An en bloc spondylectomy was performed following a posterior reconstruction in addition to anterior reconstruction utilizing an expandable cage. This device facilitates intraoperative maneuverability for surgeon, and minimizes cage migration. Therefore, the higher subsidence was found in comparison with static cages of 36.3% at 1-month follow-up and 51.6% at 1-year follow-up, which in our case could be minimized by posterior fusion two levels above and below L4.21 No excessive bleeding was noted, with an estimate of 1 L loss of blood volume without preoperative embolization. This fact is so uncommon for GCT, and such an approach could be questionable (we supposed that this drug can reduce tumor vascularization due to the calcification process in the follow-up CT scans). Denosumab is an antagonist of the RANK-L,9 inhibiting the osteoclast activation and formation of the giant cells. Hence, there was a reduction of tumor volume, and histologic evaluation post-lumbar spondylectomy showing a complete absence of the GCT inside the vertebra, and stromal neoplastic cells. This fact could bring to the spinal oncological team a different treatment paradigm22 because a less invasive and very effective treatment could be tried.

CONCLUSION

Although the management of GCT is still challenging, new options of treatment are becoming available and showing striking clinical results. Maybe in the future, denosumab therapy could become the first-line option or crucial adjuvant treatment for this disease, avoiding or facilitating complex spine surgeries. Nevertheless, well-designed studies will need to be addressed to answer this question.

Key Points.

A new spinal GCT treatment modality.

The anterior L4 spondylectomy after we started denosumab therapy.

Tomita's technique (first part: posterior approach; second part: anterior approach) is a suitable option for lumbar spinal GCT resection combined with medical therapy.

Footnotes

The device(s)/drug(s) that is/are the subject of this manuscript is/are FDA-approved or approved by corresponding national agency for this indication.

No funds were received in support of this work.

No relevant financial activities outside the submitted work.

References

- 1.Sung HW, Kuo DP, Shu WP, et al. Giant-cell tumor of bone: analysis of two hundred and eight cases in Chinese patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1982; 4:755–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szendroi M. Giant-cell tumour of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004; 86:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng MH, Robbins P, Xu J, et al. The histogenesis of giant cell tumour of bone: a model of interaction between neoplastic cells and osteoclasts. Histol Histopathol 2001; 16:297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang L, Xu J, Wood DJ, et al. Gene expression of osteoprotegerin ligand, osteoprotegerin, and receptor activator of NF-kappa B in giant cell tumour of bone: possible involvement in tumour cell-induced osteoclast-like cell formation. Am J Pathol 2000; 156:761–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell 1998; 93:165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Refai D, Dunn GP, Santiago P. Giant cell tumor of the thoracic spine: case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 2009; 71:228–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundaresan N, Boriani S, Okuno S. State of the art management in spine oncology: a worldwide perspective on its evolution, current state, and future. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009; 34 suppl 22:S7S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruka W, Rutkowski P, Morysinsk T, et al. The megavoltage radiation therapy in treatment of patients with advanced or difficult giant cell tumor of bone. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010; 78:494–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bekker PJ, Holloway DL, Rasmussen AS, et al. A single-dose placebo-controlled study of AMG162, a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL, in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 2004; 19:1059–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas D, Henshaw R, Skubitz K, et al. Denosumab in patients with giant-cell tumour of bone: an open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11:275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlin D. Giant cell tumor above the sacrum. Cancer 1977; 39:1350–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer C, Saravanja D, Dvorak M, et al. Surgical management of primary bone tumors the spine: validation of an approach to enhance cure and reduce local recurrence. Spine 2011;36: 830–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandiera S, Boriani S, Donthineni R, et al. Complications of en bloc resection in the spine. Orthp Clin N Am 2009; 40:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker W, Dohle J, Bernd L, et al. Local recurrence of giant cell tumor of bone after intralesional treatment with and without adjuvant therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90:1060–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Wei, Ji Tao, Tang X, et al. Outcome of conservative surgery for giant cell tumor the sacrum. Spine 2009; 34:1025–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leggon RE, Zlotecki R, Reith J, et al. Giant cell tumor of the pelvis and sacrum: 17 cases and analysis of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; 196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santiago-Dieppa DR, Hwang LS, Bydon A, et al. L4 and L5 spondylectomy for en bloc resection of giant cell tumor and review of the literature. Evid Based Spine Care J 2014; 5:151–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawahara N, Tomita K, Murakami H, et al. Total en bloc spondylectomy of the lower lumbar spine: a surgical techniques of combined posterior and anterior approach. Spine 2011;36: 74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boriani S, Weinstein JN, Biagini R. Primary bone tumors of the spine. Terminology and surgical staging. Spine 1997; 22:1036–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matcuk G, Jr, Patel D, Schein A, et al. Giant cell tumor: Rapid recurrence after cessation of long term denosumab therapy. Skeletal Radiol 2015; 44:1027–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau D, Song Y, Guam Z, et al. radiological outcomes of static vs expandable titanium cages after corpectomy: A retrospective analysis of subsidence. Neurosurgery 2013;72: 529–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldschlager T, Dea N, Reynolds J, et al. Giant cell tumors of the spine: Has denosumab changed the treatment paradigm? J Neurosurg Spine 2015; 20:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]