Abstract

This study aimed to determine trends in prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension in Malaysia and to assess the relationship between socioeconomic determinants and prevalence of hypertension in Malaysia.

The distribution of hypertension in Malaysia was assessed based on available data in 3 National Health and Morbidity Surveys (NHMSs) and 1 large scale non-NHMS during the period of 1996 to 2011. Summary statistics was used to characterize the included surveys. Differences in prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension between any 2 surveys were expressed as ratios. To assess the independent associations between the predictors and the outcome variables, regression analyses were employed with prevalence of hypertension as an outcome variable.

Overall, there was a rising trend in the prevalence of hypertension in adults ≥30 years: 32.9% (30%–35.8%) in 1996, 42.6% (37.5%–43.5%) in 2006, and 43.5% (40.4%–46.6%) in 2011. There were significant increase of 32% from 1996 to 2011 (P < 0.001) and of 29% from 1996 to 2006 (P < 0.05), but only a small change of 1% from 2006 to 2011 (P = 0.6). For population ≥18 years, only a 1% increase in prevalence of hypertension occurred from the 2006 NHMS (32.2%) to the 2011 NHMS (32.7%) (P = 0.25). A relative increase of 13% occurred in those with primary education (P < 0.001) and a 15% increase was seen in those with secondary education (P < 0.001). The rate of increase in the prevalence of hypertension in the population with income level RM 3000–3999 was the highest (18%) during this period. In general, the older age group had higher prevalence of hypertension in the 2006 and 2011 NHMSs. The prevalence peaked at 74.1% among population aged 65 to 69 years in the 2011 NHMS. Both the proportion of awareness and the control of hypertension in Malaysia improved from 1996 to 2006. A change in the control of hypertension was 13% higher in women than in men.

The findings suggest that the magnitude of hypertension in Malaysia needs additional attention. Strengthening the screening for hypertension in primary health-care settings in the high-risk groups and frequent health promotion to the community to enhance individual awareness and commitment to healthy living would be of immense value.

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension, the most common medical condition seen in primary health-care setting, can lead to myocardial infarction, stroke, renal failure, and premature death if not detected and treated early.1 It has been identified as the leading risk factor for global disease burden.2 The World Health Organization has highlighted that hypertension disproportionally affects populations in low- and middle-income countries where the health system is weak.3 According to the available reports, the prevalence of hypertension varies among countries, between countries in the same region, and among subgroups of populations in a country.4 Different populations have specific different determinants of hypertension. As such, empirical data emerging from any particular country is necessary to provide a baseline for monitoring and formulating better strategies tailored to the local context for prevention and control of hypertension.

Malaysia, a developing country in the Southeast Asian region with an upper income level, has a multiracial and multiethnic population of 30.07 million5 spread over 13 states and 3 federal territories. In line with modernization and a growing economy, many Malaysians have adopted new lifestyles, food habits, and dietary patterns. In Malaysia, the National Health and Morbidity Surveys (NHMSs), which included hypertension, were designed to explore the health status, health-related behavior, and health services utilization for a representative sample of the population of Malaysia.6 As such, the estimates of hypertension were available. The NHMS used stratified multistage probability samples of the Malaysia population.6–8 A large scale non-NHMS survey on hypertension was also conducted in the year 2004.9

The availability of data from repeated cross-sectional surveys is valuable for examining not only the changes in hypertension status, but also changes in related awareness, control of hypertension over time for sociodemographic determinants. Taken together, the objective of the current study was to determine trends in prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension in Malaysia from 1996 to 2011 and to assess the relationship between socioeconomic determinants and prevalence of hypertension in Malaysia during this period.

METHODS

Inclusion Criteria of the Surveys

For the current analysis, surveys were included if they reported national representative data on prevalence of hypertension and/or the levels of awareness and control of hypertension.

Operational Definitions

Ascertainment of hypertension was made on the basis of systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg,10 the Seventh Joint National Committee standards for self-reported hypertension,11 or taking antihypertensive medication.12

Participants were considered to be aware of their hypertension, if they answered “yes” to the interview question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health personnel that you had high BP?” This meant awareness of hypertension was defined by self-reporting of a prior elevated blood pressure (BP) made by a health-care staff (excluding women diagnosed during pregnancy).

Participants with SBP/DBP < 140/90 mm Hg and were taking antihypertensive medication were considered to have hypertension controlled.

Data Extraction

The current study used data from 3 NHMSs carried out in 1996,6 2006,7 and 20118,13 and 1 non-NHMS.9 This study, therefore, covered the period from 1996 to 2011.

We extracted data, using a piloted data extraction sheet prepared for the current study. Collected data included survey-related information (the year of survey, study location, study design, sampling method, sample size, and data collection tool), and hypertension-related information (confirmation of hypertension, number of people with hypertension, and age-specific and gender-specific data, wherever available).

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics was used for the characteristics of the surveys included. Differences in prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension between any 2 surveys were assessed by using a ratio, following a method described elsewhere14 (ie, estimate % in the later survey divided by estimate % in the earlier survey). We used data on the NHMS 2011 for comparison purpose, wherever possible.

Based on available data, regression analyses were employed with hypertension as an outcome variable and educational attainment and household income as predictors to assess the independent associations between the predictors and the outcome variables.

The generic equation was as follows:

У = β0 + β1χit + vi + it.

Where У is the prevalence of hypertension in the survey i in year t, χ is a vector such as educational attainment, etc. and is the error term. β0 is the constant term and β1 is the slope. The vi are random variables and Cov (χit, vi) = 0. We also investigated the model fit through regression diagnostics tests.15

An ethical approval was not necessary as the current study was carried out with the published dataset available in the public domain. Data entry was done with excel spreadsheet, whereas analysis was with STATA 12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Surveys

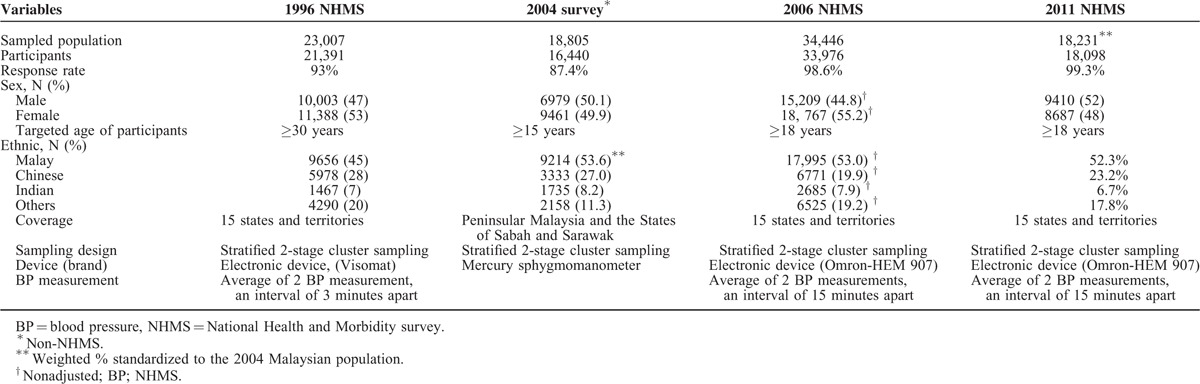

All surveys included were cross-sectional designs (Table 1). The number of participants ranged from 16,440 in the 2004 non-NHMS9 to 33,976 in the 2006 NHMS.7 The response rate ranged from 87.4% in the 2004 non-NHMS9 to 99.3% in the 2011 NHMS.8 The participants were ≥18 years in the 2006 and 2011 NHMSs,7,8 ≥30 years in the 1996 NHMS survey,6 and ≥15 years in the 2004 non-NHMS in Malaysia.9

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Surveys Between 1996 and 2011

In all 4 surveys,6–9 diagnosis of hypertension was made by Seventh Joint National Committee criteria (BP ≥ 140/90 mm Hg.16 The 3 NHMSs measured BP by digital devices, whereas the non-NHMS used mercury sphygmomanometers. All these surveys used random samplings with stratified 2-stage cluster sampling design.

Prevalence of Hypertension

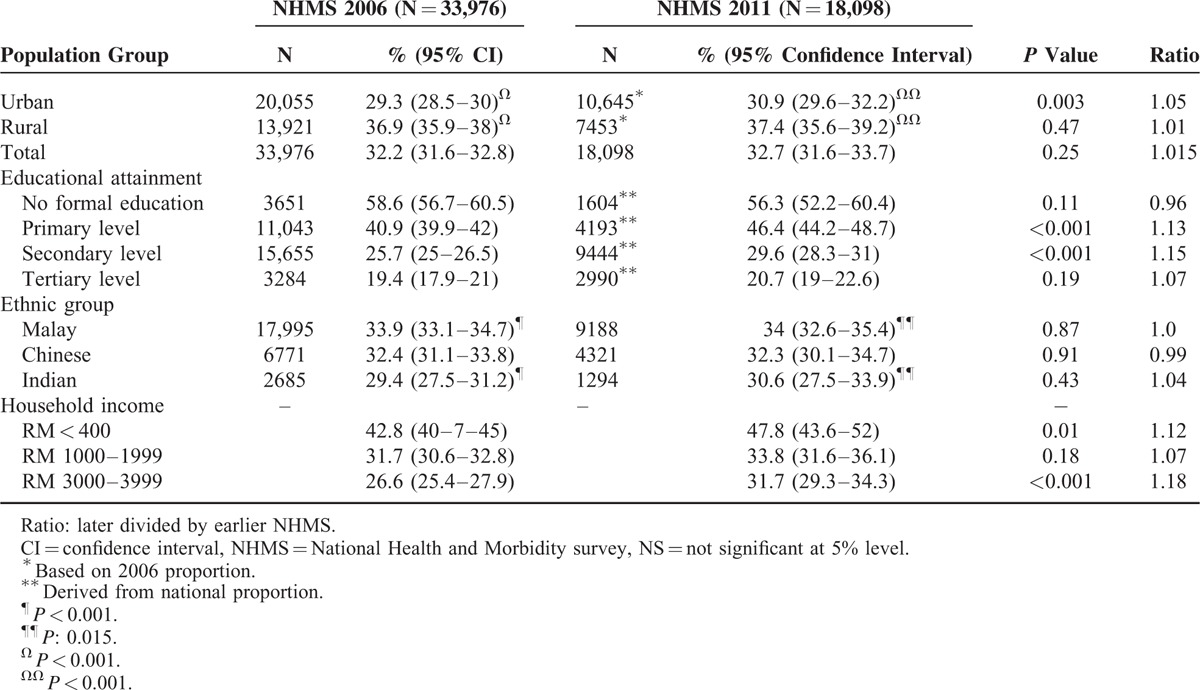

Overall, there was a rising trend in the prevalence of hypertension in adults ≥30 years: 32.9% (30%–35.8%) in 1996,6 42.6% (37.5%–43.5%) in 2006,7 and 43.5% (40.4%–46.6%) in 2011,13 with a significant increase of 32%. from 1996 to 2011 (P < 0.001) and of 29% from 1996 to 2006 (P < 0.05), but only a small change of 1% from 2006 to 2011 (P: 0.06). For population ≥18 years, only a 1% increase in prevalence of hypertension occurred from the 2006 NHMS (32.2%)7 to the 2011 NHMS (32.7%)8 (P: 0.25; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of Hypertension in Population 18 Years and Above

In general, the lower the educational level, the higher was the prevalence found in both the 2006 and 2011 NHMSs. The group with nonformal education (P: 0.25) as well as the group with tertiary level education (P: 0.19), however, had comparable prevalence from 2006 to 2011. Those with primary education (P < 0.001) as well as those with secondary education (P < 0.001) had increased trend of hypertension prevalence from 2006 to 2011. A relative increase of 13% occurred in those with primary education (P < 0.001) and a 15% increase was seen in those with secondary education (P < 0.001). Holding other factors constant, a 12.8% increase in prevalence was observed with a decrease in 1 level of educational attainment during the years 2006 and 2011.

Overall, the higher prevalence of hypertension was found among the Malays (33.9%) and the lowest level was seen among the Indians in NHMS 2006 (29.4%) (P < 0.001) and in the NHMS 2011 (34%, 30.6%) (P = 0.015; Table 2). Within ethnic group, however, showed comparable prevalence in both NHMS (P: 0.86, Malay; P: 0.91, Chinese; P: 0.43, Indian).

Hypertension prevalence increased by 12% in income level RM 400 or lower (P: 0.01), 7% in income level RM 1000–1999 (P: 0.18), and 18% in income level RM 3000–3999 (P < 0.001) from 2006 to 2011. Consistently, the highest prevalence was found in those with the lower income level (ie, level 1: RM 400 or lower) and the lower prevalence with the higher income level (ie, level 3: RM 3000–3999) between 2006 and 2011. The rate of increase in the prevalence of hypertension in the population with income level RM 3000–3999, however, was the highest (18%) (Table 2). A decrease in 1 level of income increases prevalence of hypertension by 8% (Supplemental Table 1).

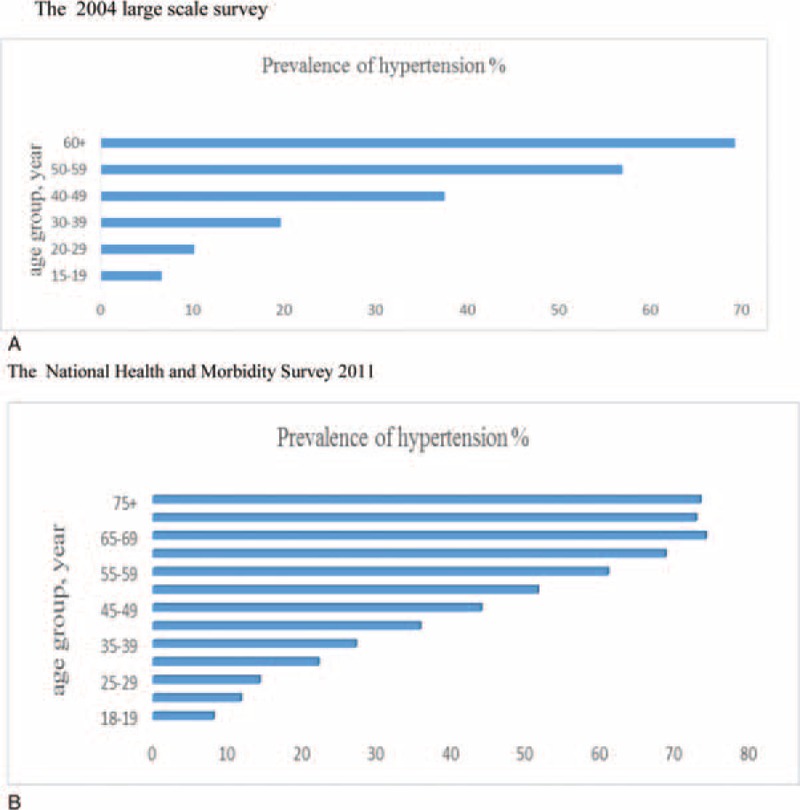

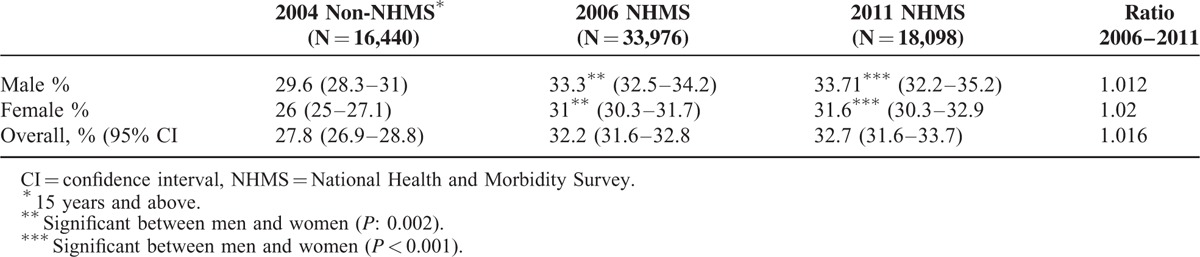

In general, the older age group had higher prevalence of hypertension in the 2004 and 2011 NHMSs (Figure 1). The prevalence peaked at 74.1% among population aged 65 to 69 years in the 2011 NHMS. Difference in cutoff points in the age grouping in these included surveys rendered comparison of the rate of change over time difficult. Based on available data, overall prevalence in ≥18 years showed a small increase of 1.6% from 2006 to 2011 (P: 0.25). When this was stratified by sex in ≥18 years, there were significant differences in prevalence of hypertension between men (33.3%) and women (31%) in the 2006 NHMS (P: 0.002) and the 2011 NHMS (33.7% versus 31.6%, P: 0.001; Table 3). The prevalence between the rural and urban settings were significantly different in both NHMS 2006 (36.9% versus 29.3%, P < 0.001) and NHMS 2011 (37.4% versus 30.9%, P < 0.001) with a higher prevalence in the rural setting from 2006 to 2011. The rate of change, however, is more pronounced in the urban community (5%), whereas this was only 1% in the rural community (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of hypertension in Malaysia stratified by age groups.

TABLE 3.

Sex-specific Prevalence of Hypertension in Adults 18 Years and Above

When stratified by states, 3 states in Malaysia, Johor, Perak, and Sarawak, had a relative increase in hypertension prevalence of 14% to 15% from 2006 to 2011 (Table 4). Perak showed an increasing trend as well as the highest hypertension prevalence in the country. The Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur showed a 1% relative increase between 2006 and 2011, but it remained below the national average (a 3% increase). An interesting observation was a 43% relative decrease in hypertension prevalence in the Federal Territory of Putrajaya, which also had the lowest level of hypertension prevalence compared with other states and federal territories.

TABLE 4.

Distribution of Hypertension Among States and Federal Territories in Malaysia

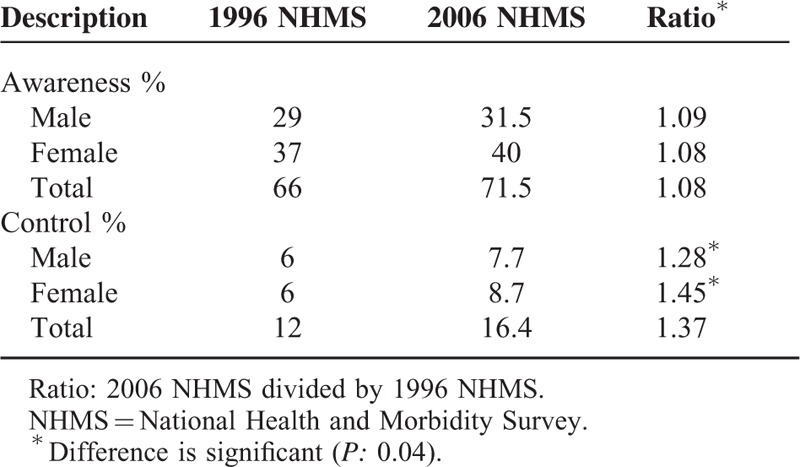

Awareness and Control of Hypertension

Based on available data from the 1996 to 2006 NHMSs,6,7 both the rate of awareness (an increase of 8%) and control of hypertension (an increase of 37%) improved over time. When stratified by sex, a slightly higher increase (0.9%, ratio 1.09/1.08) in the awareness of hypertension was found in men, whereas a 13% (ratio 1.45/1.28) rise in the control of hypertension occurred in women compared with men (P = 0.04) (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Awareness and Control of Hypertension in Population 30 Years and Above

DISCUSSION

The current study provides information on hypertension trends using data from 4 nationally representative surveys in Malaysia. The major observations are as follows.

Prevalence of hypertension was relatively higher in the older age group, in men, and in those with low educational attainment or lower household income level.

A rising trend of hypertension prevalence was found in three states of Malaysia.

The level of awareness and control of hypertension showed increasing improvement over time.

The prevalence of hypertension in Malaysia rises with increasing age. This upward trend was also reported in other parts of the world.4,16–18 Stiffening of the arteries is a well-established ageing process19 that could contribute toward this upward trend, particularly for systolic hypertension. Low educational attainment may be a proxy for low health literacy.20 Patients with adequate health literacy can read, understand, and act on health-care information.21 Also, low educational attainment may be a proxy for low income. Low socioeconomic status could have led to limited access to health care, and to ignorance of the complications of uncontrolled hypertension. Differences in personal values, beliefs, attitudes, outlook on life, and behavior could also contribute to these differences.22

A worldwide study in 17 countries reported a higher prevalence of hypertension among women.17 The current study, however, showed differently, with higher prevalence in men. In addition, there was an increase in the rate of controlled hypertension in women than men during the same period. A national survey in the year 2010 showed the labor force participation rate of Malaysian women to be 46.8% compared with 79.3% of their male counterparts.22 Thus, relatively less women could be in employment, allowing them more time to attend social groups or make frequent visits to healthcare facilities for medical checkups for themselves or their children. These factors could have contributed to a higher level of consciousness about hypertension in women, which could have contributed to a higher rate of controlled hypertension in women. Malaysia's rapid economic growth, accompanied by technological advancement, urbanization and increasing wealth could have led to changes toward an existence of convenience, luxury and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy dietary practices with instant meals, high sugar and salt intake, smoking, and drinking.23 Job stress in the competitive work environment and smoking are relatively more common in men, who are usually the major breadwinners in their families. These cumulative factors could have contributed to the higher prevalence of hypertension in men.

Interstate variation in prevalence of hypertension needs additional attention. A study in other parts of the world had highlighted that geographical variation in (diseases) burden distribution (hypertension in this case) and could be attributed to differential access of the communities to comprehensive prevention and control programs.24 The lowest prevalence rate in Putrajaya might be because of the socioeconomic determinants of the population residing there plus the fact that it is a relatively new planned garden city with good roads and no traffic congestion. Many, if not all, residences were purposely built for Government staff with relatively higher (or at least average) level of education attainment, which would be coupled with adequate health literacy. Perak state, which has the highest hypertension prevalence in the country and an increasing trend in prevalence has a mix of urban and rural settings. Equity and accessibility to healthcare services have always been highlighted as a commitment of the Malaysian government. In this perspective, inequity relates to the doctor-population ratio whereby the populations in urban areas (like in the Klang Valley), however, have better accessibility to (medical) doctors.25 Hence, early accessibility to timely health screening in the rural settings could be limited. Our findings of the relatively higher prevalence of hypertension among rural population might be related to this factor, among others. The accentuation of change in prevalence amongst urban population than in the rural population could be related to the changes in lifestyles and environment related to rapid urbanization, and competitive job stress. A reduction in the average BP could be achieved by lifestyle modification of the population, which would result in a reduced prevalence of hypertension3 as well as cardiovascular complications.

An interaction between genetic and environmental factors, such as food habit, salt intake, lifestyle, behavioral characteristics, and stress level could have contributed to the high prevalence of hypertension. A study has highlighted that racial disparity may be related to patient behavior.21 Furthermore, the heterogeneity of genetic predisposition to hypertension among different ethnic groups such as genes encoding the components of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system has emerged as potential candidates. For instance, angiotensin II type 1 receptor gene 1166A > C polymorphism (1166C allele) frequency in Malaysians was reported to be lower than other races such as Caucasians.26 Although exact mechanisms were not fully understood, animal models showed involvement of several factors in the modulation of arteriolar pressure, including G protein-coupled receptor kinase,27 the expression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV,28 and platelet antigen 2, among others.

Awareness and Control of Hypertension

The ultimate goal in the management of hypertension is to achieve control of BP in all individuals with hypertension, which is also an important public health target.29 Compared with India,30,31 the levels of awareness and control of hypertension in Malaysia were still low. Hypertension does not always cause symptoms, but hypertension is responsible for at least 45% of deaths because of heart disease and 51% of deaths because of stroke.3 In fact, controlling hypertension can prevent consequential morbidity and mortality, for example, lowering population SBP by 5 mm Hg reduces deaths because of stroke by 14%.29 The gap between hypertension awareness and controlled hypertension status implies poor compliance to medical treatment or noncompliance in taking medication, albeit with the availability of inexpensive and effective medications.

Strength and Limitations

Hypertension prevalence rates in the current study were for the noninstitutionalized and nonmilitary Malaysian population. The possibility of an underestimation is a concern. Self-reported information from a single household respondent could be subjected to recall bias. Difference in cutoff points in the age groupings in these included surveys made some difficulties in comparison of the rate of change over time. Despite these concerns, this study has provided more comprehensive information than a single survey. The NHMSs included prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in which BP measurements have followed the standard (or at least acceptable) methods and recruited large samples with appropriate sampling. The sampling frame was stratified by state and urban/rural households and by state and urban/rural residence. In doing so, these national surveys are considered to be nationally representative. Differences between the national surveys, such as survey design and geographical coverage could have contributed to differences in estimates arising from each survey.32 This, however, might be a less serious concern, compared with a single, small area survey.

IMPLICATIONS

Repeated cross-sectional health surveys, using standardized data collection procedures across populations and consistent over time, have been used to support evidence-based policy development and the planning and monitoring of health status.31 A study had highlighted that in the light of secondary level prevention, patients who strictly adhered to antihypertensive medications were 45% more likely to have controlled hypertension than those with medium or low compliances.32,33 Hence, hypertension control strategies should include measures to enhance treatment compliance as well as scaling up the community-based primary preventive measures, such as education on healthy lifestyles, particularly on weight control, reduced salt intake, modification of eating habits, and increased physical activity.29

CONCLUSIONS

The findings suggest that the magnitude of hypertension in Malaysia needs additional attention. Strengthening the screening for hypertension in primary health-care settings in the high-risk groups and frequent health promotion to the community to enhance individual awareness and commitment to healthy living would be of immense value.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participants and researchers of the national surveys included in this analysis and the International Medical University (IMU) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia for allowing us to perform this study. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers and editors for valuable inputs and comments given to update this article. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of any institution.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; CI = confidence interval; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; NHMS = National Health and Morbidity Survey; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

CN and PNY contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint national committee (JNC 8). J Am Med Assoc 2014; 311:507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380:2224–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. A Global Brief on Hypertension. Silent Killer, Global Public Health Crisis. 2013; Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/global_brief_hypertension/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Picon RV, Fuchs FD, Moreira LB, et al. Trends in prevalence of hypertension in Brazil: a systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012; 7:e48255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Indexmundi Malaysia Demographics Profile, 2014, http://www.indexmundi.com/malaysia/demographics_profile.html [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim TO, Morad Z. Hypertension Study Group. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in the Malaysian adult population: results from the national health and morbidity survey 1996. Singapore Med J 2004; 45:20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IPH (Institute for Public Health). The Third National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS III) 2006. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Ministry of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.IPH (Institute for Public Health). National Health and Morbidity Survey 2011 (NHMS 2011). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rampal L, Rampal S, Azhar MZ, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Malaysia: a national study of 16,440 subjects. Public Health 2008; 122:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Hypertension: Clinical Management of Primary Hypertension in Adults. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health (NIH). The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC7). National Institute for Health (NIH), 2004. Available online at: http://www.nhlbi.-nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/jnc7full.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. National heart, lung, and blood institute joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure; National high blood pressure education program coordinating committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. J Am Med Assoc 2003; 289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurpreet K, Guat HT, Mustapha F, et al. The epidemiology of hypertension in Malaysia: current status. 15th NIH scientific conference, incorporating the NHMS and GATS. 2012 June 12–14, Holiday Villa Subang Jaya 2012; http://www.ihm.moh.gov.my/images/files/15th-NIH-Scientific-Meeting/NIHSM-2012-LecNotes/SP5-The-Epidemiology-of-Hypertension-in-Malaysia-Dr-Gurpreet.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ezzati M, Oza S, Danaei G, et al. Trends and cardiovascular mortality effects of state-level blood pressure and uncontrolled hyper-tension in the United States. Circulation 2006; 117:905–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armitage P, Berry G. Automatic selection procedures and colinearity. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 3rd ed.1994; Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 321–323. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, et al. Worldwide prevalence of hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens 2004; 22:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, et al. PURE (prospective urban rural epidemiology) study investigators. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high, middle, and low-income countries. J Am Med Assoc 2013; 310:959–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naing C, Aung K. Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension in Myanmar: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2014; 93:e100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blacher J, Safar ME. Large-artery stiffness, hypertension and cardiovascular risk in older patients. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2005; 2:450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma YQ, Mei WH, Yin P, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in Chinese cities: a meta-analysis of published studies. PLoS One 2013; 8:e58302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hertz RP, Unger AN, Cornell JA, et al. Racial disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, and management. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:2098–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malaysian Government. Principal Statistics of Labor by Gender, Malaysia. Malaysian Government, 1990; 12–13. Available online at: http://www.statistics.gov.my/portal/download_Economics/files/DATA_SERIES/NEGERI/16MALAYSIA.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghazali SM, Seman Z, Cheong KC, et al. Sociodemographic factors associated with multiple cardiovascular risk factors among Malaysian adults. BMC Public Health 2015; 15:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.EUROASPIRE I II Group (European Action on Secondary Prevention by Intervention to Reduce Events). Clinical reality of coronary prevention guidelines: a comparison of EUROASPIRE I and II in nine countries. Lancet 2001; 357:995–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MOH (Ministry of Health). Country Health Plan. 10th Malaysian Plan. Malaysia: MOH (Ministry of Health); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rehman A, Rahman AR, Rasool AH. Effect of angiotensin II on pulse wave velocity in humans is mediated through angiotensin II type 1 (AT(1)) receptors. J Hum Hypertens 2002; 16:261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.2013; Santulli G, Trimarco B, Iaccarino G. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 20:5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanni F, Santulli G, Izzo R, et al. The Pl (A1/A2) polymorphism of glycoprotein IIIa and cerebrovascular events in hypertension: increased risk of ischemic stroke in high-risk patients. J Hypertens 2007; 25:551–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whelton PK, He J, Appel LJ, et al. National high blood pressure education program coordinating committee. Primary prevention of hypertension: clinical and public health advisory from the national high blood pressure education program. J Am Med Assoc 2002; 288:1882–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anchala R, Kannuri NK, Pant H, et al. Hypertension in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension. J Hypertens 2014; 32:1170–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE, et al. Demographic and health surveys: a profile. Int J Epidemiol 2012; 41:1602–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olives C, Myerson R, Mokdad AH, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in United States Counties, 2001–2009. PLoS ONE 2013; 8:e60308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bramley TJ, Gerbino PP, Nightengale BS, et al. Relationship of blood pressure control to adherence with antihypertensive monotherapy in 13 managed care organizations. Manag Care Pharm 2006; 12:239–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]