Abstract

Objective

The prevalence of depression in older adults has been increasing over the last 20 years and is associated with economic costs in the form of treatment utilization and caregiving, including inpatient hospitalization. Comorbid alcohol diagnoses may serve as a complicating factor in inpatient admissions and may lead to overutilization of care and greater economic cost. This study sought to isolate the comorbidity effect of alcohol among older adult hospital admissions for depression.

Methods

We analyzed a subsample (N = 8,480) of older adults (65 + ) from the 2010 Nationwide Inpatient Sample who were hospitalized with primary depression diagnoses, 7,741 of whom had depression only and 739 of whom also had a comorbid alcohol disorder. To address potential selection bias based on drinking and health status, propensity score matching was used to compare length of stay, total costs, and disposition between the two groups.

Results

Bivariate analyses showed that older persons with depression and alcohol comorbidities were more often male (59.9% versus 34.0%, p < .001) and younger (70.9 versus 75.9 years, p < .001) than those with depression only. In terms of medical comorbidities, those with depression and alcohol disorders experienced more medical issues related to substance use (e.g., drug use diagnoses, liver disease, and suicidality; all p < .001), while those with depression only experienced more general medical problems (e.g., diabetes, renal failure, hypothyroid, and dementia; all p < .001). Propensity score matched models found that alcohol comorbidity was associated with shorter lengths of stay (on average 1.08 days, p < .02) and lower likelihood of post-hospitalization placement in a nursing home or other care facility (OR = 0.64, p < .001). No significant differences were found in overall costs or likelihood of discharge to a psychiatric hospital.

Conclusions

In older adults, depression with alcohol comorbidity does not lead to increased costs or higher levels of care after discharge. Comorbidity may lead to inpatient hospitalization at lower levels of severity, and depression with alcohol comorbidity may be qualitatively different than non-comorbid depression. Additionally, increased costs and negative outcomes in this population may occur at other levels of care such as outpatient services or emergency department visits.

Keywords: older adult, depression, alcohol, hospitalization, length of stay, cost, disposition

Late-life depression among older adults is a significant public health concern. Estimates suggest that over half of people with geriatric major depression had their first onset of a major depressive episode in old age (Fiske, Wetherell, & Gatz, 2009). Recent studies have estimated the prevalence of major depressive disorder to be between 3.0% and 4.5% of the older adult population, with even higher rates, estimated at 7.2%, of adults older than 75 experiencing major depressive disorder in the past year (Aziz & Steffens, 2013). Prevalence rates for depression among adults have increased since the early 1990s, which may indicate a need for increased services as the post–World War II cohort ages (Compton, Conway, Stinson, & Grant, 2006).

Late-life depression carries with it high economic costs (Smit et al., 2006). Older adults with late-life depression use more medical services than older adults without depressive symptoms. Total health care costs are an estimated 47% to 51% higher for patients with depression as compared to those without depression, and outpatient costs are an estimated 43% to 52% higher (Katon, Lin, Russo, & Unutzer, 2003). Furthermore, older adults with depressive symptoms require more informal caregiving than their nondepressed counterparts. The estimates of this caregiving cost in the United States reach $9 billion a year (Langa, Valenstein, Fendrick, Kabeto, & Vijan, 2004).

Acute care is frequently a primary driver of costs, and depression is the primary cause of psychiatric hospitalization for older adults (Zivin, Wharton, & Rostant, 2013). Depression is associated with longer medical hospital stays, particularly for older adults (Bressi, Marcus, & Solomon, 2006). Depressive symptoms are also associated with increased emergency department use for suicide-related injuries (Carter & Reymann, 2014), disproportionate hospital admissions (Nagamine, Jiang, & Merrill, 2006), and an increased likelihood of rehabilitation needs and inpatient death (Cullum, Metcalfe, Todd, & Brayne, 2008).

Substance abuse comorbidities are a complicating factor in psychiatric inpatient admissions (Unick et al., 2011). Older adults with depression are more likely to abuse alcohol than those without depression and to have an increased likelihood of a more severe onset and course of late-life depression (Cook, Winokur, Garvey, & Beach, 1991; Devanand, 2002). Consequently, individuals with substance abuse disorders and psychiatric comorbidity have a higher number of emergency room visits and general health service utilization than individuals without psychiatric comorbidity (Curran et al., 2008; Scott, Gilvarry, & Farrell, 1998), including specifically for alcohol and depression comorbidity (Lennox, Scott-Lennox, & Bohlig, 1993). Comorbid alcohol use disorder is a risk factor for quicker rehospitalization for individuals hospitalized with major depressive disorder (Lin, Chen, Lin, & Lin, 2007).

In understanding the role of alcohol in care outcomes, it is important to recognize complexities between alcohol use and health in older adulthood. Alcohol-related conditions and heavy drinking are associated with poor health status and depressive symptoms (Kirchner et al., 2007; Sacco, Bucholz, & Spitznagel, 2009). Even though alcohol-related diagnoses may worsen health, decrements in overall health may lead to changes in drinking over time, leading older adults to cut back on drinking or abstain completely (Brennan, Schutte, Moos, & Moos, 2011; Eigenbrodt et al., 2000; Moos, Brennan, Schutte, & Moos, 2010; Satre, Gordon, & Weisner, 2007). The relationship of current alcohol use and health services utilization (such as emergency room use or inpatient hospitalization) may be confounded by differential health status, creating selection bias. This effect has been called the “sick quitter” hypothesis (Balsa, Homer, Fleming, & French, 2008; Shaper, Wannamethee, & Walker, 1988) among older adults. Simply put, older adults who drink may be healthier due to the effect of abstention among those in poor health.

While current research has found that both alcohol and depressive disorders increase health care utilization, few studies have considered the potential additive effect of alcohol disorder on outcomes of inpatient depression admissions specifically (Saleh & Szebenyi, 2005). Thus, this study uses a nationally representative sample of all payer hospitals to examine how the presence of a comorbid alcohol condition influences the cost, length of stay, and disposition (mortality and placement) of older adult patients being treated for a primary depression diagnosis in the hospital. We hypothesized that alcohol comorbidity would be associated with greater costs, length of stay, risk of death, and placement in intermediate care.

METHODS

Data Source

This analysis utilized data from the 2010 Nationwide Inpatient Survey (Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, 2012), a 20% national probability of community hospital discharges in the United States. Data were collected from participating states by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, a part of the Administration on Healthcare Research and Quality. In 2010, the Nationwide Inpatient Survey contained 7,800,819 unique discharges. For each discharge, information about length of stay, charges, diagnoses, patient demographics, hospital characteristics, patient disposition, and other variables were collected. The survey sampled hospitals using a stratified cluster sampling strategy, which were stratified by ownership status, bed size, teaching status, urban/rural location, and U.S. region; data were weighted to calculate national estimates. The current study was ruled not human subjects research by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board.

Analysis Sample

For this study, we analyzed admissions for a primary diagnosis depression-related condition among individuals aged 65 years and older. Data were subset to admissions in which the primary diagnoses included major depressive disorders, mood and depressive disorders not otherwise specified, and dysthymia based on ICD-9-CM classifications. In the 2010 Nationwide Inpatient Survey, there were 10,178 such admissions, which translate to 145.78 per 100,000 adults aged 65 or older admitted with these conditions. Of those admissions, 909 (8.9%) had documented alcohol-related comorbidity, or 2.59 per 100,000 adults aged 65 or older. Among individuals with comorbid alcohol-related disorders, alcohol abuse and dependence was the most common diagnoses in 91.1% of admissions. Alcohol intoxication (8.4%) and alcohol withdrawal (9.2%) were diagnosed in some admissions as well. Alcohol-related memory problems (i.e., delirium, dementia, and amnesia) were less common (4.6%), and alcohol-induced mental health problems (e.g., psychosis) were diagnosed in 1.5% of comorbid cases.

Because data on race (12.9%) and ZIP code–based income (1.2%) were not provided by the some states, we imputed these variables using weighted sequential hot deck imputation using SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, 2012). In cases where hospital characteristics were missing (.6%), admissions were excluded from the analysis. Because of our interest in current alcohol problems, we excluded cases where patients were transferred from another hospital or institution, leaving a total sample of 8,480 cases. These cases include 7,741 in the untreated (non-alcohol comorbid) group and 739 in the treated (alcohol comorbid) group.

Variables

Alcohol-Related Comorbidity

In the analysis subsample, patient admissions were classified as either having alcohol-related comorbidity or not based on the presence of alcohol-related ICD-9-CM codes including alcohol-induced medical disorders, alcohol-induced psychotic and other mental health conditions, intoxication, alcohol abuse or dependence, and alcohol-related toxicity. The comorbidity variable was coded dichotomously.

Hospital Outcome Indicators

Data analysis focused on four major outcomes: length of stay, total hospital charges, death, and disposition type. Length of stay was the number of days spent in the hospital for the episode of care. Hospital total charges were the total amount of charges in dollars for that admission. For patient disposition, we looked at a number of indicators including hospital mortality, transfer to some form of intermediate care, or transfer to a freestanding psychiatric hospital. A discharge was coded as intermediate care if they went to a short-term hospital, skilled nursing facility, cancer center, federal health care facility, swing bed, inpatient rehabilitation facility, long-term care hospital, or critical access hospital. Psychiatric transfers were coded based on whether a person was discharged to a freestanding psychiatric hospital. In-hospital mortality was based on whether a patient died during the hospital stay.

Covariates

Demographic, clinical, and hospital covariates were used to develop propensity scores to compare hospital outcomes between those with alcohol-related comorbidity and those without comorbidity. Demographic measures included female gender, dummy-coded race (White, Black, Latino, Asian, Native American, and other), age in years, and median household income quartile for the patient’s ZIP code ($1 to $38,999, $39,000 to $47,999, $48,000 to $62,999, $63,000 + ). Matching clinical variables included comorbidities associated with aging and/or alcohol use (pulmonary/circulation, diabetes, renal failure, hypertension, valvular disease, aids, drug use, liver disease, psychosis, hypothyroid, dementia, and suicidality). These comorbidity variables were developed by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project and were selected for this study based on studies of multimorbidity in older adults (Barnett et al., 2012; Salive, 2013). Additionally, admissions were matched on a four-level severity variable (1 = minor loss of function; 2 = moderate loss of function; 3 = major loss of function; 4 = extreme loss of function) provided by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Hospital covariates included hospital region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), whether the hospital is in an urban area, and hospital size based on the number of beds (small, medium, large).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in three steps. First, univariate and bivariate analyses were conducted on hospital outcomes (e.g., length of stay) and relevant individual and hospital covariates based on alcohol comorbidity status among admissions where the primary diagnosis was depression-related. These analyses used weights and sample design variables provided by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project to adjust for complex sampling design. Second, we developed propensity score matched models to compare depression admissions with alcohol comorbidity to depression admissions without alcohol comorbidity. Propensity score matching is a method for estimating the treatment effect of a condition (i.e., alcohol comorbidity) on an outcome (e.g., hospital length of stay) when it is not feasible to randomize cases, as is common in observational studies. This method attempts to adjust for sampling bias by modeling a propensity score that balances the sample based on the likelihood of being a case (i.e., comorbid depression and alcohol). In propensity score–matched models, logistic regression is utilized to create propensity scores. Cases are then matched based on propensity values. We used propensity score matching specifically to address selection bias resulting from the so-called “sick quitting” effect (Shaper et al., 1988), where those with comorbid alcohol use diagnosis may have better overall health.

Propensity score–matched models were developed using sociodemographic variables (gender, race, age in years, and median ZIP code income), diagnostic comorbidities, functional severity, and hospital characteristics. Last, we compared length of stay, total charges, and disposition between propensity score matched cases to adjust for observed confounding variables.

All bivariate analyses were conducted using the SUDAAN statistical package (Research Triangle Institute, 2012) and adjusted for the complex sampling structure inherent in the Nationwide Inpatient Survey sample. Propensity score analysis was carried out using the “teffects” command in Stata (Statacorp, 2013). We used a 1 to 3 nearest neighbor match with a caliper of 0.18, which is 2 times the standard deviation of the propensity score estimates. Matching analysis used the average treatment effect estimator included in Stata’s teffect psmatch command. The propensity score–matched model was robust to changes in the matching algorithm, number of matching control subjects, and size of the caliper.

The third analytic step was to use multivariate logistic regressions to model the odds of being discharged to an intermediate care facility versus being discharged home and being discharged to a psychiatric hospital versus being discharged home. Both logistic regression models used comorbid alcohol disorder as the primary independent variable and adjusted estimates for the list of covariates in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Depression-Related Admissions by Alcohol Diagnostic Status (N = 8480)

| No Alcohol Comorbidity (n = 7,741) | Alcohol Comorbidity (n = 739) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | [95% CI] | M | [95% CI] | Wald F | p | |

| Length of stay | 10.06 | [9.40, 10.71] | 8.00 | [7.36, 8.65] | 5.05 | <.001 |

| Total charges | $22324 | [$20228,$24033] | $18967 | [$16193, $21742] | 2.29 | .023 |

| Disposition | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | t | p |

| Home | 69.83% | [65.25%, 74.05%] | 83.45% | [79.19%, 86.99%] | 33.38 | <.001 |

| SNF/MED | 26.68% | [22.50%, 31.32%] | 13.20% | [9.91%, 17.36%] | 35.90 | <.001 |

| Psychiatric hospital | 2.14% | [1.72%, 2.67%] | 2.47% | [1.39%, 4.34%] | .23 | .64 |

| Died | .13% | [.06%, .28%] | 0 | (0, 0) | — | — |

Note. CI = confidence interval; SNF/MED = skilled nursing facility/intermediate care facility.

RESULTS

Unadjusted Models

Table 1 displays unadjusted data on hospital outcome measures by alcohol comorbidity status. Depression admissions without alcohol-related comorbidity had an average length of stay of 10.06 days, longer than those with comorbid alcohol disorders and depression, who had an average length of stay of 8.00 days (Wald F = 5.05; p < .001). Similarly, among those admitted without comorbid alcohol diagnoses mean charges for comorbid individuals were $22,324, higher than for those admitted without a comorbid alcohol diagnosis ($18,967; Wald F = 2.29; p < .023).

We found similar differences for disposition status based on alcohol comorbidity; those admitted for depression without an alcohol use disorder were discharged to higher levels of care. Lower percentages of those without alcohol comorbidity were discharged home (69.83%) than those with depression with alcohol comorbidity (83.45%) and had higher rates (26.68%) of discharge to intermediate health care facilities such as nursing homes compared with those admitted for depression with comorbid alcohol use disorders (13.20%). In-hospital mortality among individuals in the sample was very low in the depression without comorbidity group and no one with alcohol comorbidity died in the hospital.

In addition to differences in unadjusted hospital outcomes, there were a number of significant differences in those admitted for depression with alcohol-related comorbidity (see Table 2). In terms of gender, 65.98% of those with depression without comorbid alcohol diagnoses were women, compared with 39.95% of those with depression and a comorbid alcohol related problems. Those with a depression diagnosis without alcohol comorbidity were significantly older (75.91 years) than those admitted with depression and comorbid alcohol diagnoses (70.93 years). Higher percentages of individuals with depression without a comorbid alcohol condition (29.57%) resided in areas with the lowest ZIP code income category ($1 to $38,999) compared with 24.93% of those with depression and alcohol comorbidity. The reverse was observed at the $48,000 to $62,999 ZIP code income level, with 23.91% admitted with depression without alcohol comorbidity and 28.62% admitted with depression and a comorbid alcohol disorder.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Depression-Related Admissions by Alcohol Diagnostic Status

| Demographic, Clinical, and Hospital Characteristics | Depression Without Alcohol Comorbidity (n = 7,741) | Depression With Alcohol Comorbidity (n = 739) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics | M | SE | M | SE | |

| Age | 75.91 | .2 | 70.93 | .32 | <.001 |

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender (female) | 5112 | 65.98 | 296 | 39.95 | <.001 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 6426 | 82.94 | 627 | 84.61 | .33 |

| Black | 634 | 8.27 | 59 | 8.22 | .97 |

| Latino | 365 | 4.74 | 33 | 4.47 | .83 |

| Asian | 70 | .92 | 3 | .44 | .13 |

| Native American | 60 | .75 | 2 | .25 | .08 |

| Other | 183 | 2.35 | 14 | 1.87 | .29 |

| Income (by ZIP code) | |||||

| $1–$38,999 | 2341 | 29.57 | 187 | 24.93 | .04 |

| $39,000–$47,999 | 2025 | 26.05 | 176 | 23.73 | .23 |

| $48,000–$62,999 | 1827 | 23.91 | 210 | 28.62 | .02 |

| $63,000 + | 1547 | 20.46 | 166 | 22.72 | .27 |

| Individual comorbidities | |||||

| Pulmonary/circulation | 52 | .69 | 2 | .27 | .06 |

| Diabetes | 1758 | 22.67 | 121 | 16.56 | <.001 |

| Renal failure | 565 | 7.22 | 19 | 2.55 | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 5452 | 70.56 | 504 | 68.30 | .23 |

| Valvular disease | 261 | 3.35 | 15 | 1.97 | .02 |

| Drug use | 320 | 4.17 | 108 | 14.85 | <.001 |

| AIDS | 2 | .03 | 2 | .28 | .20 |

| Liver disease | 45 | .58 | 38 | 5.25 | <.001 |

| Psychosis | 134 | 1.70 | 14 | 1.90 | .71 |

| Hypothyroid | 1580 | 20.36 | 88 | 11.92 | <.001 |

| Dementia | 2283 | 29.46 | 104 | 14.16 | <.001 |

| Suicidality | 1568 | 20.35 | 266 | 36.21 | <.001 |

| Functional severity | <.001 | ||||

| Minor | 5 | .05 | 1 | .10 | |

| Moderate | 6684 | 72.44 | 734 | 81.52 | |

| Major | 1950 | 21.04 | 139 | 15.72 | |

| Extreme | 592 | 6.47 | 23 | 2.67 | |

| Hospital characteristics | |||||

| Hospital region | |||||

| Northeast | 1608 | 20.49 | 168 | 22.30 | .48 |

| Midwest | 2232 | 28.24 | 153 | 20.69 | .007 |

| South | 3358 | 43.80 | 313 | 43.06 | .82 |

| West | 543 | 6.86 | 105 | 13.95 | <.001 |

| Urban hospital | 6238 | 82.14 | 638 | 87.94 | .008 |

| Hospital size | |||||

| Small | 1071 | 12.74 | 90 | 11.12 | .34 |

| Medium | 2060 | 26.74 | 183 | 24.98 | .61 |

| Large | 4610 | 60.51 | 466 | 63.90 | .32 |

| Teaching hospital | 3059 | 40.32 | 303 | 41.29 | .77 |

Medical conditions were different based on alcohol comorbidity as well. Medical conditions not generally related to substance use were more common in admissions diagnosed with depression but no alcohol comorbidity, including diabetes, renal failure, valvular disease, hypothyroid, and dementia. Conditions potentially related to alcohol use, such as drug use diagnoses, liver disease, and suicidality, were significantly more common among those with depression with alcohol co-morbidity. Consistent with comorbidity differences, the ordinal level of functional severity suggested that levels of severity were higher among those without comorbid alcohol problems.

Hospital characteristics were also associated with comorbid diagnostic status (i.e., depression with alcohol). Admissions with comorbid alcohol diagnosis to urban hospitals were slightly more common than among those with non-alcohol comorbid depression (see Table 2). Greater percentages of depression admissions were alcohol comorbid in the Western region and lower percentages were comorbid in the Midwest region.

Propensity Score Matched Adjusted Models

We constructed a model to estimate the probability of being in the comorbid alcohol disorder group and used those probabilities to match individuals in the depression diagnosis–only group. The matching criteria and quality are detailed in Table 3. The match produced an appropriate number of control participants who could be matched to the comorbid alcohol and depression participants, and there was a substantial reduction in bias associated with the match. The purpose of the matching was to identify individuals with no comorbid alcohol disorder who had a similar health profile to those in the comorbid alcohol and depression group. Table 3 shows that the treatment and matched groups were not statistically different on any of the matching covariates.

TABLE 3.

Propensity Score Matching Assessment

| Non-Matched

|

Propensity Score—Matched

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Match Variables | t | p | Bias | t | p | Bias | Bias Reduction |

| Individual Characteristics | |||||||

| Gender (female) | −42.9% | −3.1% | 92.7% | ||||

| Race | |||||||

| Black | −.83 | .41 | −0.6% | −.28 | .78 | −1.1% | −77.9% |

| Latino | −8.20 | <.001 | −6.5% | 1.31 | .19 | 4.8% | 26.3% |

| Asian | −7.35 | <.001 | −6.5% | −.38 | .71 | 4.8% | 78.6% |

| Native American | 5.56 | <.001 | 4.0% | .0 | 1.00 | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Other | −3.97 | <.001 | −3.1% | .82 | .41 | 3.4% | −8.7% |

| Age (in years) | 12.14 | <.001 | 10.2% | −.10 | .921 | −0.2% | 98.3% |

| Individual Comorbidities | |||||||

| Diabetes | 15.34 | <.001 | −12.3% | .67 | .51 | 4.5% | 63.8% |

| Renal failure | −11.45 | <.001 | −9.7% | .28 | .78 | 2.0% | 79.4% |

| Hypertension | 4.82 | <.001 | 3.7% | .48 | .63 | 2.6% | 29.2% |

| AIDS | 6.49 | <.001 | 4.5% | .0 | 1.00 | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Liver disease | 31.40 | <.001 | 19.8% | .28 | .78 | 2.0% | 79.4% |

| Psychosis | 2.34 | .02 | 1.8% | .53 | .59 | 2.9% | −65.5% |

| Hypothyroid | −15.55 | <.001 | −12.6 | .80 | .43 | 5.3% | 57.7% |

| Dementia | 22.90 | <.001 | −20.0% | −.27 | .79 | −2.9% | 85.3% |

| Suicidality | 17.90 | <.001 | 13.0% | −.25 | .80 | −1.3% | 90.2% |

| Functional severity | |||||||

| Major | −5.47 | <.001 | −4.3% | .24 | .81 | 1.8% | 58.4% |

| Extreme | −12.12 | <.001 | −10.3 | .11 | .92 | 0.8% | 92.7% |

| Hospital characteristics | |||||||

| Hospital region | |||||||

| Midwest | −5.57 | <.001 | −4.3% | .11 | .92 | 0.5% | 88.1% |

| South | −12.72 | <.001 | −9.8% | −.75 | .45 | −4.0% | 59.2% |

| West | 9.44 | <.001 | 7.1% | .33 | .75 | 1.8% | 75.2% |

| Urban hospital | 2.56 | .011 | 2.0% | −.20 | .84 | −1.1% | 46.7% |

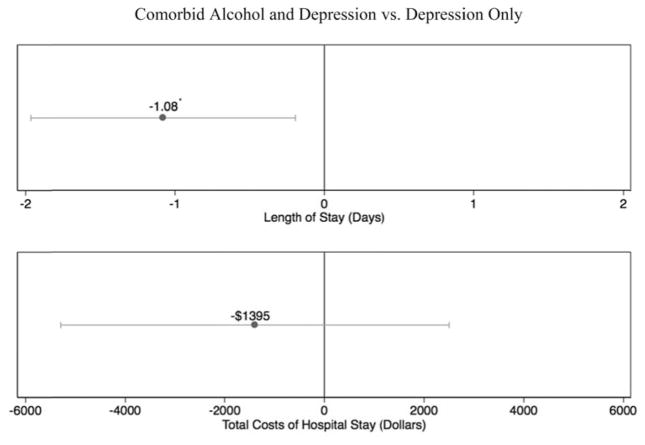

Figures 1 and 2 show the coefficients for two outcomes: length of stay and total costs. Being in the co-morbid alcohol and depression group was associated with 1.08 (p = .02) fewer days in the hospital compared to the depression-only group. While individuals in the comorbid alcohol and depression group had costs that were $1,395 lower than in the depression diagnosis–only group, the mean difference was not statistically significantly different from 0 (p = .48).

FIGURE 1.

Propensity score model estimates of length of stay and costs of stay. *p < .05.

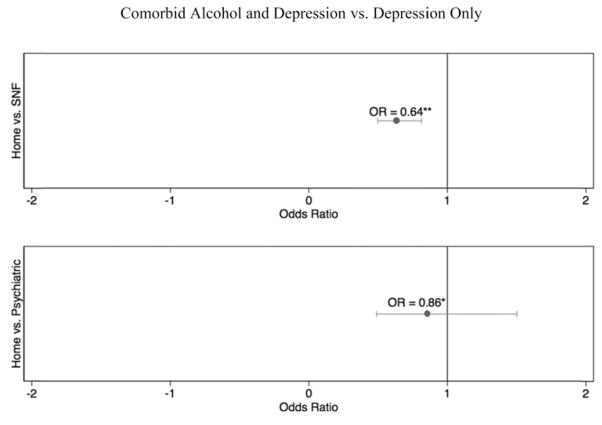

FIGURE 2.

Logistic models of disposition. Note. SNF = skilled nursing facility. *Not significant; **p < .001.

Logistic Regression Discharge Models

Figure 2 displays the odds ratios for the comorbid alcohol and depression diagnosis group compared to the depression diagnosis–only group for being discharged home versus a skilled nursing facility and home versus a psychiatric facility. We adjusted the odds ratio for the variables identified in Table 2. Having a comorbid alcohol disorder was associated with 36% lower odds of being admitted to a skilled nursing facility (OR = 0.64, p < .001) versus home. There was no statically significant difference in being admitted to a psychiatric facility versus home.

DISCUSSION

Our findings run counter to the notion that comorbid alcohol and depressive disorder is associated with higher utilization and cost when compared with depression only. There are several potential explanations for this counterintuitive finding. First, we could have not adequately adjusted for health conditions. Given that the strength of the Nationwide Inpatient Survey data set is its coding of health conditions, we find this explanation unpersuasive. A second explanation is that services system factors lead to a lower health threshold for admitting individuals with a comorbid alcohol disorder. These reasons include lack of treatment alternatives for older adults. Given that other studies have found similarly lower thresholds for admission of comorbid mental health and substance abuse patients and subsequently shorter stays and lower level discharges, we find this to be a plausible explanation (Stulz et al., 2014; Unick et al., 2011). A third explanation is that individuals admitted with depression only represent distinct depression subtypes in older adults, which have distinct clinical courses with resulting different lengths of stay.

Alcohol Comorbidity and Admission Thresholds

Even with matching, comorbid alcohol disorder was not associated with longer stay or greater costs. Factors associated with comorbid alcohol use among older adults, such as low utilization of preventative care and other psychiatric comorbidity, may lower the threshold for admission, leading alcohol comorbid individuals’ lower overall severity to be admitted. Merrick et al. (2011) identified a greater likelihood of an emergency department visit for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions among heavy drinking older adults. Similarly, those with alcohol-related diagnoses may be admitted with lower overall depression severity, because alcohol use disorders are associated with increased risk of suicide in older adults (Blow, Brockmann, & Barry, 2004; Conwell, Duberstein, & Caine, 2002). In a study of emergency department admissions for suicidality, Carter and Reymann (2014) found an increased likelihood of hospital admission for drug use, but not alcohol specifically.

If individuals with alcohol-related comorbidity are admitted with lower levels of severity, the course of treatment may be less expensive and shorter in individuals with non-comorbid depression, leading to earlier discharge. Similarly, alcohol-related diagnoses were commonly abuse and dependence diagnoses: detoxification and intoxication. The presence of these conditions may encourage specific psychiatric care. Studying treatment of depression among older adult veterans, Burnett-Zeigler et al. (2012) found that depressed older adults with psychiatric comorbidity were more likely to receive specialty care with psychotherapy and medication, while those without psychiatric comorbidity were more likely to receive treatment with medications in general medical settings.

Qualitative Differences in Comorbid Depression?

There may be a distinct set of differences between older adult depression admissions with alcohol disorder and those without alcohol use disorder. In non-matched models, a counterintuitive finding was that alcohol comorbidity was associated with shorter length of stay, inpatient costs, and lower likelihood of transfer to another medical setting. Dementia comorbidity was much higher in the depression-only group, a factor related to increased costs of care and length of stay (Lyketsos, Sheppard, & Rabins, 2000). Kales et al. (1999) found that veterans had greater inpatient utilization for comorbid depression and dementia than for either condition alone, but these differences did not extend to outpatient care. It should be noted that propensity score models included dementia diagnoses, limiting the possibility that differences can be explained by dementia diagnosis itself.

It is possible that the types of treatment needs among individuals with alcohol comorbid depression are less intensive (e.g., day treatment or outpatient care) versus among those with depression only. For instance, Vetrano et al. (2014) found that chronic alcohol consumption was associated with shorter length of stay in acute care settings. Research evidence suggests that the relationship of alcohol consumption and depression is not linear, in that depression severity does not appear to be associated with higher consumption levels (Skogen, Harvey, Henderson, Stordal, & Mykletun, 2009) and that alcohol consumption may not be an exacerbating factor in treatment of older adults with depression (Oslin, Katz, Edell, & Ten Have, 2000). Complex system interactions and severity profiles suggest that diagnosis of an alcohol-related disorder is not simply an exacerbating factor worsening outcomes for patients.

Limitations

This analysis includes a number of notable strengths including the use of a large nationally representative data set and the use of a sophisticated approach that addresses known potential confounds in comparing comorbidity. Still, our findings should be interpreted in light of a number of limitations. Because comorbidity was measured using formal diagnostic coding, it is possible that older adults who had comorbid alcohol related problems were under-represented. Using diagnostic categories, we did not address potential differences in severity specific to depression or alcohol disorders, only overall functional impairment. Propensity score–matched models are designed to address the issue of confounding resulting from observed covariates, not unobserved confounding factors (i.e., endogeneity). Individuals admitted to the hospital for depressive disorders may suffer from conditions that are the result of previous alcohol use. Longitudinal research has found that the development of health problems may lead to cessation of drinking among problem and heavy drinkers (Moos et al., 2010). With the exception of alcohol-related organ failure, these may not be captured in diagnostic coding, leading to the underestimate of alcohol’s effects to those with current diagnostic level problems. Finally, our findings are applicable to single episodes of care and should not be interpreted to apply to the overall cost of care for individuals with comorbid conditions within inpatients settings or across levels of care.

Implications for Further Research

Our findings suggest that alcohol comorbidity itself is not associated with higher costs, greater length of stay, or discharge to a higher level of care during a single episode of care. From the standpoint of geriatric mental health care, a number of issues should be considered. First, providers should recognize that alcohol comorbidity is not necessarily an indicator of adverse inpatient outcomes during a single episode of inpatient care. Second, the effect of alcohol on service utilization may be spread across levels of care (e.g., partial hospitalization) and systems of care (e.g., substance abuse specialty care) in the form of readmission, psychiatric care, and overall system costs. Research with older veterans suggests that increased service utilization among individuals with dual diagnosis occurs in outpatient rather than inpatient care (Kerfoot, Petrakis, & Rosenheck, 2011). Future research on health outcomes should consider inpatient treatment in the overall context of care. It is possible that shorter lengths of stay among those with depression and an alcohol use disorder are offset by readmission, higher outpatient costs, or inadequate care at the inpatient level.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

Support for this research was provided from an internal grant from the University of Maryland, School of Social Work.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors of this paper, Paul Sacco, Jay Unick, Faika Zanjani, and Elizabeth Camlin have no conflicts of interest that would influence the validity of this study.

References

- Aziz R, Steffens DC. What are the causes of late-life depression? Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2013;36(4):497–516. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa AI, Homer JF, Fleming MF, French MT. Alcohol consumption and health among elders. Gerontologist. 2008;48(5):622–636. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow FC, Brockmann LM, Barry KL. Role of alcohol in late-life suicide. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:48S–56S. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2004.tb03603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos BS, Moos RH. Twenty-year alcohol-consumption and drinking-problem trajectories of older men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol & Drugs. 2011;72(2):308–321. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressi SK, Marcus SC, Solomon PL. The impact of psychiatric comorbidity on general hospital length of stay. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2006;77(3):203–209. doi: 10.1007/s11126-006-9007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett-Zeigler I, Zivin K, Ilgen M, Szymanski B, Blow FC, Kales HC. Depression treatment in older adult veterans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;20(3):228–238. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ff6655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter MW, Reymann MR. ED use by older adults attempting suicide. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014;32(6):535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Changes in the prevalence of major depression and comorbid substance use disorders in the United States between 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2141–2147. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2141. doi:10.1176appi.ajp.163.12.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):193–204. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01347-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, Winokur G, Garvey MJ, Beach V. Depression and previous alcoholism in the elderly. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;158:72–75. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ff6655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullum S, Metcalfe C, Todd C, Brayne C. Does depression predict adverse outcomes for older medical inpatients? A prospective cohort study of individuals screened for a trial. Age and Ageing. 2008;37(6):690–695. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Sullivan G, Williams K, Han X, Allee E, Kotrla KJ. The association of psychiatric comorbidity and use of the emergency department among persons with substance use disorders: An observational cohort study. BMC Emergency Medicine. 2008;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanand DP. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in late life depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):236–242. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigenbrodt ML, Fuchs FD, Hutchinson RG, Paton CC, Goff DC, Jr, Couper DJ. Health-associated changes in drinking: A period prevalence study of the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) cohort (1987–1995) Preventive Medicine. 2000;31(1):81–89. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5:363–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Introduction to the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kales HC, Blow FC, Copeland LA, Bingham RC, Kammerer EE, Mellow AM. Health care utilization by older patients with coexisting dementia and depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(4):550–556. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, Unutzer J. Increased medical costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(9):897–903. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerfoot KE, Petrakis IL, Rosenheck RA. Dual diagnosis in an aging population: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders, comorbid substance abuse, and mental health service utilization in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2011;7(1–2):4–13. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2011.568306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner JE, Zubritsky C, Cody M, Coakley E, Chen H, Ware JH, … Levkoff S. Alcohol consumption among older adults in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(1):92–97. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0017-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa KM, Valenstein MA, Fendrick AM, Kabeto MU, Vijan S. Extent and cost of informal caregiving for older Americans with symptoms of depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(5):857–863. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennox RD, Scott-Lennox JA, Bohlig EM. The cost of depression-complicated alcoholism: Health-care utilization and treatment effectiveness. Journal of Mental Health Administration. 1993;20(2):138–152. doi: 10.1007/bf02519238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Chen YS, Lin CH, Lin KS. Factors affecting time to rehospitalization for patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2007;61(3):249–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JME, Rabins PV. Dementia in elderly persons in a general hospital. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):704–707. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick ES, Hodgkin D, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Panas L, Ryan M, … Saitz R. Older adults’ inpatient and emergency department utilization for ambulatory-care-sensitive conditions: Relationship with alcohol consumption. Journal of Aging and Health. 2011;23(1):86–111. doi: 10.1177/0898264310383156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos BS. Older adults’ health and late-life drinking patterns: A 20-year perspective. Aging & Mental Health. 2010;14(1):33–43. doi: 10.1080/13607860902918264. doi:10.1080 13607860902918264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamine M, Jiang J, Merrill CT. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) statistical briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 2006. Trends in elderly hospitalizations, 1997–2004: Statistical brief #14. Internet. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63499/ [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Katz IR, Edell WS, Ten Have TR. Effects of alcohol consumption on the treatment of depression among elderly patients. Amercan Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2000;8(3):215–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN language manual, release 11. Research Triangle Park, NC: Author; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco P, Bucholz KK, Spitznagel EL. Alcohol use among older adults in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions: A latent class analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(6):829–838. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh SS, Szebenyi SE. Resource use of elderly emergency department patients with alcohol-related diagnosis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salive ME. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2013;35(1):75–83. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxs009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, Gordon NP, Weisner C. Alcohol consumption, medical conditions, and health behavior in older adults. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2007;31(3):238–248. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.31.3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Gilvarry E, Farrell M. Managing anxiety and depression in alcohol and drug dependence. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23(6):919–931. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper AG, Wannamethee G, Walker M. Alcohol and mortality in British men: Explaining the U-shaped curve. Lancet. 1988;2(8623):1267–1273. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92890-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skogen JC, Harvey SB, Henderson M, Stordal E, Mykletun A. Anxiety and depression among abstainers and low-level alcohol consumers. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Addiction. 2009;104(9):1519–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit F, Cuijpers P, Oostenbrink J, Batelaan N, de Graaf R, Beekman A. Costs of nine common mental disorders: Implications for curative and preventive psychiatry. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2006;9(4):193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statacorp. Stata statistical software: Release 13. College Station, TX: Statacorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stulz N, Nevely A, Hilpert M, Bielinski D, Spisla C, Maeck L, Hepp U. Referral to inpatient treatment does not necessarily imply a need for inpatient treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0561-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unick GJ, Kessell E, Woodard EK, Leary M, Dilley JW, Shumway M. Factors affecting psychiatric inpatient hospitalization from a psychiatric emergency service. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2011;33(6):618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetrano DL, Landi F, De Buyser SL, Carfì A, Zuccalà G, Petrovic M, … Onder G. Predictors of length of hospital stay among older adults admitted to acute care wards: A multicentre observational study. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2014;25(1):56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.08.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivin K, Wharton T, Rostant O. The economic, public health, and caregiver burden of late-life depression. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2013;36(4):631–649. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]