Abstract

Lipids are emerging as key regulators of membrane protein structure and activity. Such effects can either be attributed to modification in bilayer properties (thickness, curvature and surface tension) or to binding of specific lipids to the protein surface. For G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs), the effect of phospholipids on receptor structure and activity remains poorly understood. Here we reconstituted purified β2-adrenergic receptor in High-Density-Lipoparticles to systematically characterize the effect of biologically relevant phospholipids on receptor activity. We observe that the lipid head-group type affects ligand binding (agonist and antagonist) and receptor activation. Specifically, phosphatidylgycerol markedly favors agonist binding and facilitates receptor activation while phosphatidylethanolamine favors antagonist binding and stabilizes the inactive state of the receptor. We then show that these effects can be recapitulated with detergent-solubilized lipids, demonstrating that the functional modulation occurs in the absence of a bilayer. Our data suggest that phospholipids act as direct allosteric modulators of GPCR activity.

INTRODUCTION

Protein sequences have evolved so as to optimize function within a given environment and, as such, membrane proteins have adapted to accommodate the physico-chemical properties of the lipid bilayer. As a corollary, changes in the composition of the lipid bilayer may affect the structure and the function of membrane proteins 1. The role of lipids in such modulation has often been discussed as either “specific”, where bound lipid act as chemical partner, or “bulk”, where given physical properties of the membrane are responsible for the effect on protein function. Numerous studies have demonstrated that bilayer thickness, curvature and surface tension can significantly influence the behavior of embedded proteins 2, 3. On the other hand, binding of given lipidic species to specific binding pockets may be required for protein stability and/or activity 3, 4. High-resolution structures have illustrated such tight binding in a variety of cases 5, 6 and in several instances the presence of lipids was actually required for crystallogenesis 2, 7, 8 Furthermore, crystal structures of proteins obtained in the presence of bound lipids have shown conformational changes when compared to similar structures obtained in the absence of bound lipids 4.

For G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs), earlier studies (typically based on depletion by cyclodextrin) have indicated that cholesterol is a key player in providing appropriate environment for receptor function (reviewed in 9). This was originally viewed as a modulation of the lipid order by cholesterol itself and/or the requirement for cholesterol-rich microdomains for efficient signaling 10, 11 but direct cholesterol-receptor interactions had also been described 12. Remarkably, the effect of cholesterol on GPCR function is receptor-dependent. For example, cholesterol modulates agonist binding to oxytocin receptors 13 and serotonin receptors 14 whereas in the case of the NTS1 receptor its presence allows for dimerization 15. Stability studies of detergent-solubilized receptors and high-resolution structures have demonstrated binding of cholesterol molecules to a conserved motif located between helices 1, 2, 3 and 4 16, 17. Still, the effect of cholesterol on the order and fluidity of the membrane may be an important parameter for receptor function 18.

The role of phospholipids on GPCRs has been studied by following protein function after reconstitution in given lipidic environments. Early work on rhodopsin suggested that bulk properties of the bilayer may modulate GPCR function 19-22 while structural studies indicated that specific rhodopsin-PE interactions are also at play 23. Furthermore, addition of solubilized phospholipids to the transducin-rhodopsin complex significantly improved light-induced activation 24. Recent studies on NTS1 receptor reconstituted in nanodiscs have indicated that change in phospholipid composition may alter G protein coupling without affecting agonist binding 25.

In this context, a clear picture on how biologically relevant phospholipids affect GPCR function is lacking and, in particular, it is not known whether given lipidic species are interacting with receptors to modulate their activity. Taking advantage of the recent availability of appropriate biochemical tools, we use the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2R) to systematically characterize the effect of biologically relevant lipid species on receptor function. Our data show that lipids act as specific modulators of β2R activity.

RESULTS

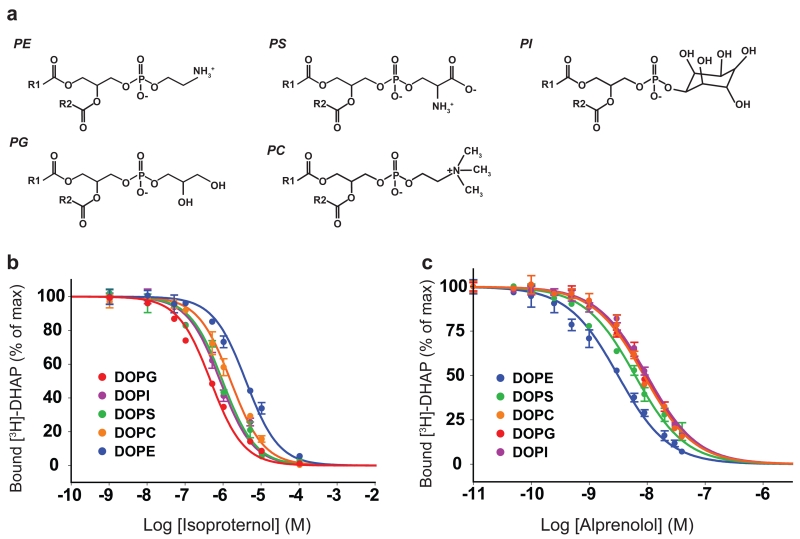

Purified human β2R receptor was reconstituted in High-Density-Lipoparticles (HDLs, or nanodiscs) of defined homogenous composition. We opted for HDL reconstitution over proteoliposomes in order to avoid the critical issue of protein orientation. In addition, previous studies have demonstrated that the β2R can be reconstituted as a fully functional monomer in HDL 26. We focused on the main lipids observed in membranes of mammalian cells, as detected by quantitative mass-spectrometry analysis of HEK293 membranes: phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylinositol (PI) (Fig. 1a). We selected 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycerol (two chains of 18 carbons with one unsaturated double bond) lipids because they are among the most abundant in mammalian membranes and all have transition temperatures below 0°C, allowing for efficient reconstitution. Conditions for reconstitution of β2R into HDL were optimized for each lipid species (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1&2).

Figure 1. Lipids modulate ligand affinity of β2R.

a. Chemical structure of the lipids used for in this study. For clarity the acyl chains are not shown and replaced by R1 and R2 labels.

b-c. Ligand binding curves for the agonist Isoproterenol and the antagonist Alprenolol competing against [3H]-dihydroalprenolol ([3H]-DHA) for β2R reconstituted in rHDL particles of different lipid compositions.

For each reconstitution we tested binding of agonist and antagonist by competition with a radiolabelled ligand (3H–DHA). As shown in Fig. 1, the binding affinities are strongly modulated by the phospholipid type surrounding the receptor. The IC50 for the agonist isoproterenol is about 5.9*10−7M when the receptor is reconstituted in DOPG but increases to 4.3*10−6M when the receptor is in DOPE, a 7.2 fold difference (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). Statistical analysis (see Methods) shows that pIC50(DOPG)≈ pIC50(DOPS)≈ pIC50(DOPI)< pIC50(DOPC)≈ pIC50(DOPE) where “<” implies statistically significant difference with p<0.05 and ≈ implies no statistically significant difference. Remarkably, the behavior is dramatically changed when comparing agonist and antagonist binding (Fig. 1c) with DOPE providing the better environment for binding the antagonist alprenolol, and DOPG, DOPC and DOPI the least efficient. The statistical test shows that pIC50(DOPE)< pIC50(DOPS)< pIC50(DOPG)≈ pIC50(DOPC)≈ pIC50(DOPI). This also demonstrates that the receptor is properly reconstituted in each one of the lipid compositions and suggests that specific lipids may favor a given functional state of the β2R.

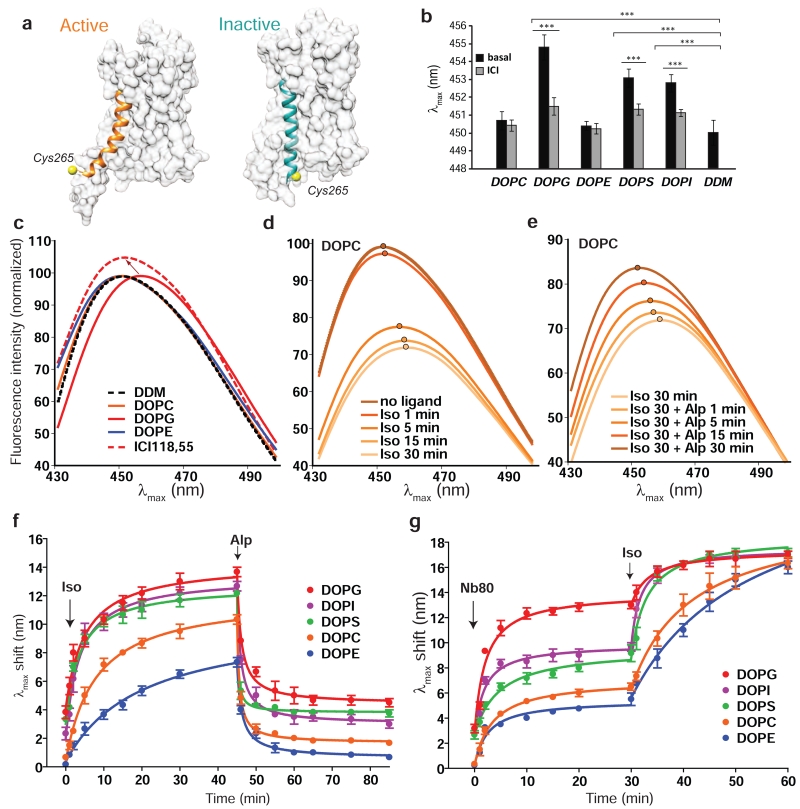

These results suggest that lipid head-groups have allosteric effects on the β2R structure. To directly examine the effect of phospholipids on receptor conformation, we monitored the fluorescence of a conformational reporter on the cytoplasmic end of TM6. Upon activation of the β2R, TM6 opens outward by about 14Å 27. This movement can be detected by monitoring the florescence properties of a bimane probe covalently bound to Cys265, because the outward movement of TM6 leads to an increase solvent exposure of bimane (Fig. 2a) and thus a decrease in fluorescence intensity along with a red-shift of the emission maximum 28. After reconstituting bimane-labelled receptor in each lipidic composition we measured fluorescence emission spectra and compared them to the signal observed for detergent-solubilized receptor. For DOPC and DOPE, this basal signal (agonist-free) is similar to the one observed in detergent, with a λmax of about 450nm (Fig. 2b) but a significant red shift is observed when the receptor is reconstituted in DOPG where the λmax is about 455nm (Fig. 2b and 2c) as well as DOPI and DOPS (Fig. 2b). This increased solvent exposure of Cys265 is not due to partial destabilization of the receptor as it can be reversed upon addition of the inverse agonist ICI118,55 (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. β2R activation is regulated by phospholipids.

a. Molecular surface representation of the active (PDB id: 3SN6) and inactive (PDB id: 4GBR) structures of the β2R with TM6 highlighted (colored ribbon) and the position of Cys265 (in yellow), showing the increased exposure of the latter in the active state.

b. Wavelength of the emission maximum fluorescence (λmax) in the absence of ligand (basal) and after addition of 100μM of inverse agonist ICI-118,551 for bimane-labelled receptors reconstituted in rHDLs of different lipid compositions compared with DDM solubilized receptor. Asterisk denotes statistically significant difference (p<0.05).

c. Basal fluorescence emission spectra for bimane-labelled receptors in rHDL of DOPC, DOPG and DOPE in comparison with DDM solubilized receptor. The effect of the inverse agonist (ICI-118,551) on β2R in DOPG rHDL is represented by dashed red curve. Blue shift in λmax is highlighted by an arrow.

d. Time dependent fluorescence change on β2R rHDL in DOPC upon addition of saturating concentration of 200μM agonist (Isoproterenol). The λmax positions are highlighted on each curve.

e. Fluorescence recovery of agonist-stimulated receptor shown in d upon the addition of saturating 100μM antagonist (Alprenolol).

f. Time dependent changes in bimane λmax upon addition of Isoproterenol (200 μM) followed by Alprenolol (100μM) for labelled receptor reconstituted in the different rHDLs. Data are the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.g. Time dependent changes in bimane λmax upon addition of 4μM Nb80 followed by agonist activation (200μM Isoproterenol). Data are the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

As the agonist-induced opening of TM6 will lead to a time-dependent decrease in bimane fluorescence, the intensity and kinetics of activation can be followed by monitoring the red-shift in the λmax of bimane emission (Fig. 2d, the λmax is highlighted with filled dots on each curve). Similarly, reversal of the TM6 opening upon addition of saturating concentration of antagonist will lead to a fluorescence recovery that results in a blue-shift in the λmax (Fig. 2e). We have therefore used the time dependent changes in λmax to directly compare the effect of the lipidic environment on receptor activation. We monitored the rate and magnitude of changes in λmax upon addition of 200 μM of the agonist isoproterenol (Fig. 2f) to β2R reconstituted into different lipids. We observed the fastest rate of change and the largest shift in λmax (relative to basal fluorescence in detergent) for DOPG, followed by DOPI and DOPS. The smallest change and slowest rate of change was observed for DOPE, with DOPC being intermediate. These results parallel the effect of lipids on the binding affinity of isoproterenol.

Testing the effect of lipids on effector coupling is complex as the G protein interacts directly with the membrane and thus changes in coupling efficiency may be due to modified affinity of the G protein for the membrane, altered receptor behavior, or combination of both. Therefore, isolating the respective contributions may be very difficult, as observed in the case of the NTS1 receptor, where PG increased G protein coupling without affecting receptor pharmacology 25. In the case of the β2R, this issue can be circumvented by using nanobody Nb80, a G protein surrogate that does not interact with the bilayer but stabilizes a true active state of the receptor27 and behaves as a G protein mimetic from a pharmacological standpoint 29. As shown in Fig. 2g, the ability of Nb80 to stabilize an active conformation is strongly influenced by the lipidic composition and here again DOPG provides the better environment for activation, reaching a λmax shift of 13 nm after 30 min. Interestingly, DOPS and DOPI do not stabilize the Nb80-bound active state as well as DOPG, indicating that a negative charge on the headgroup is not sufficient to fully stabilize the active conformation. Considering the respective sizes of the polar head-groups (PS ≈ PG < PI), these differences are not likely to arise from variability in charge density. In agreement with our other assays, DOPE provides the least supportive environment for Nb80-induced β2R activation. Interestingly, upon addition of a saturating concentration of isoproterenol, each lipidic composition allows for complete stimulation as measured by a final λmax shift of 18nm, observed in every case, further demonstrating that the β2R is fully functional in the different nanodiscs.

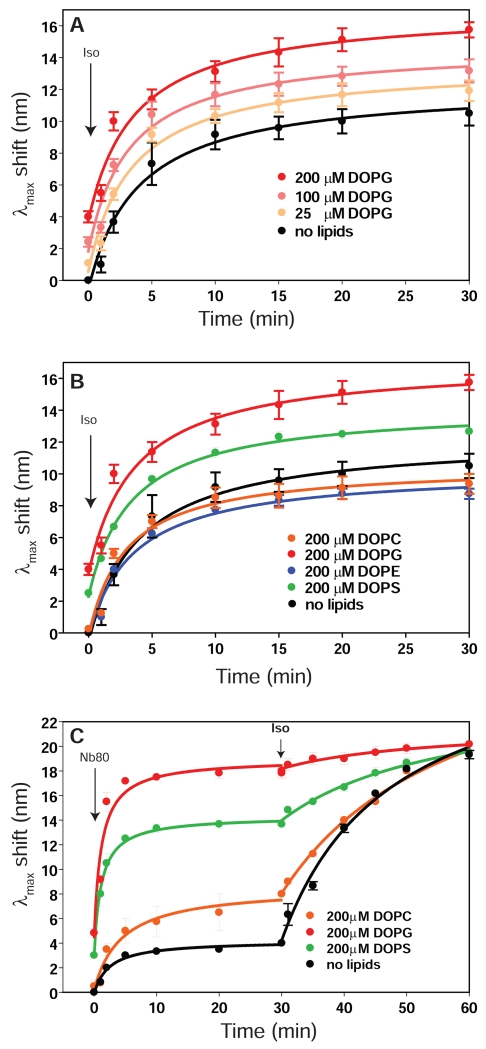

The limited size of a HDL particle implies that only a few lipid layers surround the reconstituted beta2R, indicating that bulk effect of lipids observed in native membranes or lipid vesicles should be limited in such system30. We tested this hypothesis by adding detergent-solubilized lipids on purified β2R in the absence of apolipoprotein. We verified using size-exclusion chromatography, dynamic light scattering and electron microscopy that no liposomes were formed under these conditions (Supplementary Fig.3).

As shown in Fig. 3a, adding increasing amounts of solubilized DOPG leads to a dose-dependent positive effect on β2R activation as the bimane fluorescence is affected quicker and stronger than in the absence of lipids. A dose-dependent basal λmax shift is observed, reaching 4nm at 200μM of solubilized DOPG. When comparing different solubilized phospholipids at this concentration, DOPG remains the strongest positive modulator; DOPS also shows a positive effect albeit not as strong, while DOPC and DOPE show little or no effect (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Modulation of β2R function by lipids does not require a bilayer.

a. Time dependent changes in bimane λmax of solubilized bimane-labelled β2R (1μM receptor, 500μM DDM) upon addition of saturating concentration of 200μM Isoproterenol in the presence of increasing concentration of solubilized DOPG (with 600 μM Sodium Cholate). No lipids condition was performed in presence of 600 μM sodium cholate. Data are the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

b. Time dependent changes in bimane λmax upon addition of saturating concentration of 200μM Isoproterenol in the presence of 200 μM of either DOPC, DOPG, DOPE and DOPS (detergent concentrations are identical to those in panel a). Data are the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

c. Time dependent changes in bimane λmax upon addition of 4μM Nb80 followed by agonist activation (200μM Isoproterenol). Data are the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

Stabilization of the active state by Nb80 is also modulated by lipids (Fig. 3c) in the absence of a bilayer, with DOPG facilitating a fast and large change in bimane fluorescence, reaching an almost completely active state even before addition of agonist. Here also DOPS provides a positive modulation of the activation, although not as strong as DOPG. The combination of G protein mimetic and saturating concentration of agonist leads to full activation in all conditions tested including in the absence of lipids.

While our functional data suggests a possible physiological role for PG in the activity of the β2R, this lipid is a minor component in mammalian cell membranes, representing just over 2% of all detected phospholipids. We thus investigated whether the receptor binds preferentially this lipid. To this end, we purified β2R expressed in Sf9 cells with half the detergent concentration normally used to prepare the samples (0.5% vs. 1% DDM), leading to significant increase in retained lipids (see Supplementary Table 2). These bound lipids were extracted and quantitatively measured, allowing to compare the relative amounts of each phospholipid bound to the receptor with those found in Sf9 membranes (see Methods).

As shown in Supplementary Table 2, while PG constitutes about 4% of total lipids in Sf9 membranes, it represents over 16% of all β2R-bound lipids. In fact, the receptor appears to favor binding of specific PG species such as DOPG, constituting about 0.1% of all Sf9 lipids but over 7% of all receptor bound phospholipids (Supplementary Table 3). In total, specific PG species found on the purified receptor (18:1–18:1 and 18:1–16:1) are increased about 15 fold compared to the insect cell membrane. For PC and PE we observed modest relative enrichment. While the total amount of stably bound lipids is probably underestimated due to the inevitable use of detergent for protein solubilization, our data argue that β2R and phosphatidylglycerol are likely to interact even with low natural abundance of PG.

DISCUSSION

Taken together, our data demonstrate that lipids act as modulators of GPCR structure and activity, and that this effect is driven by the head-group. Both binding studies and agonist-induced conformational assays show that DOPG, DOPS and DOPI are promoting β2R activation, while DOPE appears to favor the inactive state. The effect of lipids on the β2R structure can be observed in the absence of ligand (Fig. 2c, Fig. 2g and Fig. 3c), demonstrating that they are not due to interactions between the lipids and the ligands.

A key finding is that the negatively charged lipids favor receptor activation in the absence of a bilayer and in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3a and 3b), thus acting as true positive allosteric modulators. The presence of these lipids enhances the constitutive activity of the receptor as detected by the redshift of bimane fluorescence in the absence of ligand (Fig. 3).

In the absence of agonist and lipids, Nb80 shows a mild effect on bimane fluorescence (ie about 4nm max shift in λmax after 10 mins, Fig. 3c), which correlates with the limited basal activity of the receptor under these conditions as this nanobody strictly requires opening of TM6 for binding. The level of stimulation at steady state must reflect the balance between the dynamics of the conformational transition of the receptor (ie. relative time spent in the active and inactive state) and the specific off-rate of the nanobody. Both in nanodiscs and in solution, we observe a highly cooperative effect of negatively charged lipids as their addition dramatically potentiates the ability of Nb80 to stabilize the active state (Fig 2g and Fig. 3c). This effect is lipid-specific as the magnitude correlates with the ability of each lipid species to increase constitutive activity of the receptor (Fig. 2b), thus confirming that the nanobody Nb80 acts as a sensor of basal activity. It is unlikely that the differences between the lipid species are due to differences in affinity for the receptor as we observed them in nanodiscs (Fig. 2g) where the very high local concentration of lipids ensures permanent interaction. Rather, these variations most likely indicate that the lipids differentially affect the conformational kinetics of the receptor, e.g. that binding of DOPG maintains the cytoplasmic side of the β2R in an open conformation for a longer (average) time than binding of other lipids, leading to a larger apparent stimulation by Nb80, with almost complete receptor activation after 10 mins (Fig. 2g and Fig. 3c). This suggests that binding of such negatively charged lipids favors TM6 opening through specific binding of the head-group to the protein, most likely on the intracellular side of the receptor.

Recent studies have shown that, even at saturating concentration of full agonist, the majority of the receptor population adopts an inactive or intermediate conformation, indicating that each agonist-bound receptor spends only a limited time in the active state 31, 32 and that additional binding of a G protein (or G protein mimetic) is required to completely shift the receptor ensemble towards the active conformer. We observe a similar behavior here as, in several conditions (for example in absence of lipids, see Fig. 3a and 3b), only partial λmax shifts of bimane labeled receptor are observed even after more than 30 min of incubation with 200 μM of isoproterenol; full activation is consistently observed in the presence of both agonist and Nb80 whether or not lipids are present. However the time-dependence of this activation greatly depends on the presence of lipids, thus showing that they act as allosteric modulators that primarily regulate the kinetics of the process.

In the presence of negatively charged lipids the effect of the agonist on activation of the receptor population is greatly enhanced. As this effect is observed at saturating concentrations of isoproterenol, it is unlikely that these lipids act in an agonist-like fashion on the receptor, but rather that they stabilize the active conformation of the cytoplasmic side of the β2R. This would also be consistent with a direct interaction of the lipid at the intracellular end of the receptor. However, in contrast to what is observed with Nb80 (Fig. 2g), we do not see strong differences between the three negatively charged lipids on isoproterenol response (Fig. 2f). While this could imply a different molecular mechanism than the one potentiating Nb80 (i.e. another lipid binding site), it could also be simply due to kinetic effects (for example if the off-rate of the agonist is slower than that of Nb80).

Specific and direct lipid-protein interactions have been demonstrated for a variety of membrane proteins5, including mammalian ones7, and in a number of cases this interaction is essential for protein activity 3, 6. It is reasonable to expect that GPCRs may also contain phospholipid binding sites that would be coupled to the activation mechanism. The strong effect of negatively charged phospholipid would suggest ionic interactions between receptor side chains and lipid head-group. In addition the stronger effect observed with DOPG compared to DOPS or DOPI indicates a clear level of specificity, suggesting that given sequence motifs of the receptor interact directly with the phosphatidylglycerol head-group.

Identification of such binding sites typically relies on structural studies. Crystallizing the β2R in complex with PG could locate the binding sites involved on positive allosteric modulation, assuming that lipids will be present in the crystal and sufficiently ordered. However such studies will face practical challenges as β2R is typically crystallized in lipidic cubic phases that may dilute out or compete with bound lipids, or that the allosteric lipids may promote intermediate states not compatible with crystallization.

A key question that will also require detailed identification of the lipid binding site is whether the functional coupling to lipid binding is receptor-dependent. Adding lipids greatly enhanced stability and function of detergent-solubilized rhodopsin with negatively charged lipids (DOPS) having the strongest effect on the activation rate 24. Work on nanodisc-reconstituted rhodopsin has also shown that the presence of PG enhances arrestin-induced active state (meta-II) formation 33, but direct interaction between the effector and the lipids could possibly be responsible for the effect. For the NTS1 receptor, no difference in ligand affinity was observed upon changes in the lipidic composition, including variations in the amount of PG, in contrast to what we observed with the β2R. 25. Note however that G protein coupling to the NTS1 receptor was increased in PG nanodiscs, although this effect could be due to G protein-PG interactions.

While our data show that direct lipid binding affects receptor function, they do not rule out additional modulation of the β2R by bulk properties of the membrane. Early studies on rhodopsin have focused on identifying global properties of the bilayer as determinant of receptor state or conformational transition. As increasing the relative amount of PE appeared to favor the meta-II state, Brown and colleagues have proposed that membrane curvature stress is a key element in supporting the activation of the photoreceptor 20. In contrast, our data show that phosphatidylethanolamine tends to stabilize the inactive state of the β2R. As the lipidic composition of rod outer segment (ROS) is different from most plasma membranes 34, rhodopsin may show specific adaptation to the physico-chemical properties of its surrounding membrane. On the other hand, reconstitution of rhodopsin in HDL particles have demonstrated native-like transducing activation 35 and photointermediates 36, indicating that bulk effects are not required for rhodopsin function.

Note that testing bulk effects on the β2R receptor would require reconstitution in larger structures than HDLs but, as mentioned earlier, the lipidic composition of proteoliposomes may strongly affect the orientation of the receptor which, unlike for rhodopsin, will alter ligand access and thus void comparisons of pharmacological profiles.

Considering the magnitude of the effects observed in vitro, it is legitimate to ask how they will translate in vivo. As different tissues will typically display distinct lipidic compositions, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the actual pharmacology of a given receptor may vary from one organ to another due to change in lipid composition. Not only the apparent affinity of a given ligand for its target receptor could be different from tissue to tissue, our data suggest that the kinetics of response would also be modulated by the lipidic composition. Variations in ligand response with cellular background have been described in the past for several GPCRs 37 but are typically attributed to difference in signaling or regulatory partners. Our study suggests that the phospholipid composition of the cell type or lipid domain might play a key role.

ONLINE METHODS

All lipids used in this study were purchased from Avanti® polar lipids inc.β2AR cold ligands Isoproterenol hydrochloride I6504, Alprenolol hydrochloride A7686, ICI-118,551 I127 and Monobromobimane 69898 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich®.

Cell culturing and β2R expression

The constructs ofβ2R used in this study are 365N and PN1.β2AR-365N contains the human wild-type coding sequence of theβ2AR with a FLAG epitope tag at the aminoterminus. A sequence containing a TEV cleavage site was introduced between the FLAG epitope and the start of the receptor. The third glycosylation site was removed by mutating N187E and the receptor sequence was terminated after Gly365.β2AR-PN1 contains the human wild-type coding sequence of theβ2AR with a FLAG epitope tag at the aminoterminus. A sequence containing a TEV and 3C protease cleavage site were introduced respectively between Val24 and Thr25 and Gly365 and Tyr 366 of the receptor. The third glycosylation site was removed by mutating N187E and the receptor sequence was terminated after Gly365. Four mutations were introduced to the construct M96T, M98T, C378A and C406A. The sequences were cloned into the pFastBac1 Sf9 insect cell expression vector (Invitrogen). Expression ofβ2R for purification was achieved in SF9 cells. 4L of cells were infected with bacculovirus encoding for one of theβ2R constructs (365N or PN1) and grown in ESF 921 protein free medium from Expression system at 27°C with 130 rpm agitation for 48-50h. Cells were then harvested and pellets stored at −80°C for purification.

β2R purification and bimane labelling

β2R was purified from Sf9 cells using a three-step purification procedure as described previously38. Briefly, cell pellets were lysed in lysis buffer (10mM Tris pH 7.4, 1mM EDTA, 1 uM alprenolol, protease inhibitors) and centrifuged (15 min at 30,000g). Lysed cells were resuspended in solubilization buffer (20mM HEPES pH 7.4, 100mM NaCl, 1% dodecylmaltoside, 1μM alprenolol, protease inhibitors) and homogenized with 10 rounds of potter and then stirred for 1 h at 4 °C. Solubilized receptor was purified by chromatography using M1 Flag antibody affinity resin (sigma). The eluate from the M1 anti-Flag column was further purified on an alprenolol-sepharose affinity column and finally through a second M1 flag antibody affinity resin purification step. For bimane labeling, Flag pure receptor (50-70nmol) was incubated on ice with 100uM TCEP then 20μM mBBr in presence of protease inhibitors for at least 2h, then and 2mM Iodoacetamide were added for 30min and 5 mM cysteine were added to quench Iodoacetamide before proceeding to Alprenolol-M1 Flag affinity purification as described above.

HDL reconstitutions

ApoAI used for HDL reconstitutions was purified as described 39. Reconstitution ofβ2R in HDL particles of different lipid compositions was done based on methods previously published 26 Briefly, the reconstitution mix consisted on the following: 3.6mM detergent (cholate), 1.2mM lipids, and 72-100μM apoA-I (depending on the lipid composition) and 5μM purifiedβ2R. Lipids were solubilized with 20mM Hepes, pH 8/100 mM NaCl/1 mM EDTA plus 50 mM detergent. Purified apoA-I was mixed (at least 10-fold excess) to receptor then solubilized lipids added. ApoAI/lipid ratio was optimized for each lipidic composition in order to have homogeneous HDL population; we used a range of 1/30 to 1/50. Reconstitution mix incubated O.N. on ice, and then samples were subjected to BioBeads (BioRad, Hercules, CA) to remove detergents, resulting in the formation of rHDL particles. rHDLs were then injected on a Superdex200 300GL (GE Healthcare) size exclusion column in HNE buffer (20mM HEPES, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA) and the main homogeneous peak kept. Samples were stored on ice until used. If necessary,β2R rHDL particles from receptor-free rHDL were subsequently purified by M1-anti-FLAG immunoaffinity chromatography. Purifiedβ2R rHDL particles were eluted with 1mM EDTA plus 200ug/ml FLAG peptide and stored on ice.

Electron Microscopy

rHDL formation and homogeneity were further checked by electron microscopy. Grids were treated in a glow discharge system over 1 min in a low current regime, 5 mA, 2 μl of β2R rHDL sample at 10 μg/ml were used per grid and stained with Uranyl Formate 0.75%.TEM data was collected at magnification 60000 and pixel size 1.9Å/px in a Jeol Jem-1400 operating at 120 kV with a LaB6 filament and equipped with a CMOS TEMCAM-416 4016×4016.

Radioligand binding affinities

Competition binding assays were performed using [3H]-dihydroalprenolol (DHA) on reconstituted β2R. Concentrations of [3H]-DHA used was 1 nM. Competing ligands were added at following concentrations: 10−11 to 10−4 M for cold antagonist (alprenolol) and 10−13 to 10−1 M for cold agonist (isoproterenol). The assays were carried out for 60 min at room temperature with shaking at 130 rpm. Reactions were harvested on a Brandel haverster M-24T on GF/B filters.

All data points were obtained in duplicates and experiments were repeated at least three times. Data were normalized and fit to theoretical one-site competition binding models using Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). A one-way ANOVA plus a posteriori Scheffe statistical test was used to compare pIC50 values. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 21, with p < 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

Bimane fluorescence spectroscopy on solubilized or reconstituted in HDL particles β2R

To compare lipids effect on receptor conformation β2R was labelled with the environmentally sensitive fluorescent probe monobromobimane (Invitrogen) at cysteine 265 located in the cytoplasmic end of TM6. Fluorescence spectroscopy was performed on a Photon Technology International (PTI) fluorometer, digital mode, using excitation and emission bandpass of 6nm. Excitation wavelength was set at 370nm and emission was collected from 430 to 510nm 1nm increments with 0.5scm−1. Spectra were registered at 25°C as mean of two. 1μM of bimane labeled receptor in 0.025% DDM or in rHDL particles was used for each measure. The lipid effect on basal activity of rHDLs β2R was quantified as the red-shift of bimane λmax compared to the detergent solubilized receptor. For basal activity inhibition, the receptor was treated with 100μM inverse agonist ICI-118,551 and λmax blue shift monitored. A two-way ANOVA plus a posteriori Scheffe statistical test was used to compare λmax values. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 21, with p < 0.05 considered as statistically significant. Conformation changes upon ligand binding were assayed using saturating concentrations of agonist Isoproterenol (200μM) and antagonist Alprenolol (100μM). Effect on coupling was measured in presence of 4μM (4 molar excess) Nb80 (G protein-mimetic nanobody29) followed by the addition of 200μM Isoproterenol. Kinetics of maximum wavelength (λmax) Shift was monitored for each condition with at least 6 time points. The initial value was established a the λmax of condition without ligand - λmax of receptor in DDM without ligand nor lipid. For the effect of lipids on DDM solubilized receptor, 25, 100, or 200μM lipids in sodium cholate were added to the receptor. Ratios of lipids/receptor/detergent were as following:

2 μM lipids/1μM β2R/75μM cholate/500μM DDM; 100μM lipids/1μM β2R /300μM cholate/500μM DDM; 200μM lipids/1μM β2R /600μM cholate/500μM DDM; and (non-lipidated control) 0μM lipids/1μM β2R/600μM cholate/500μM DDM.

Kinetic curves were drawn using Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) as mean of at least 3 independent experiments.

Mass spectrometry identification and quantification of lipids in SF9 membranes and bound to purified β2R

Lipid extraction and mass spectrometry analysis of lipids from SF9 membranes and SF9 purified β2R was performed as following: Briefly, cell pellets of 6*107 SF9 cells were transferred into hypotonic lysis buffer (10mM Tris pH7.4, 1mM EDTA) and stirred for 15min for cell breaking. Lysed cells were centrifuged at 25000g for 10 min and the pellet containing the membranes was resuspended in PBS. Standards for each phospholipid class and cholesterol-13C3 were added to the SF9 membrane or 1-2mg purified receptor and lipids were then extracted from membranes by methanol/chloroform extraction as described in 40 with the following modifications: 10μL HCl 6N were added to the mixture and extraction was repeated 3 times on the same sample to have maximum recovery of all types of lipids; corresponding organic phases were pooled together, the solvent evaporated under nitrogen stream and lipids then dissolved in dichloromethane:Isopropanol (1:4) prior to mass spectrometry analysis. Samples were injected in a rapid resolution liquid chromatography system (RRLC 1200 series from Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) fitted with a XDB Eclipse Plus C18, 4.6×150 mm, 1.8 μm. A 6520 series electrospray ion source (ESI) - quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-TOF) from Agilent Technologies was used for the MS/MS analyses in positive and negative mode. Data were acquired by the Mass Hunter Acquisition® (Agilent Technologies). For quantification, single MS analyses were performed and data were acquired by the Mass Hunter Acquisition® (Agilent Technologies). For data analysis, first fragment based searching mode analysis by Mass Hunter Qualitative Analysis® (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) was applied on MS/MS spectra in positive and negative mode to identify lipid species. Then for quantification, samples were run in simple MS mode. Extracted ion chromatograms were extracted based on the exact masses of the lipids observed during auto MSMS analyses. Phospholipids were quantified by the standard curves run during the set of experiments.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1:Size-exclusion of β2R rHDLs of different lipidic compositions

Size-exclusion chromatography profiles of the various rHDL using a Superdex 200/300GL column (GE Healthcare) showing one major peak in all cases. The main peak was collected for subsequent functional assays.

Supplementary Figure 2: Homogeneity and particle size analysis ofβ2R rHDLs in different lipidic compositions.

Transmission electron micrographs for negatively stained rHDLs of different lipid compositions. Defined homogeneous particles of 9-12.5 nm depending on the lipid used were observed. Particle sizes in each environment were measured and mean diameter ± SEM in nm is shown in the table.

Supplementary Figure 3: Solubilized lipids do not form bilayer

Transmission electron micrographs for negatively stained samples ofβ2R + solubilized DOPG (1μMβ2R, 200μM DOPG, 500μM DDM and 600 μM sodium cholate), showing particle size of about 8 nm, as expected for receptor/detergent micelles. No liposome was observed.

Supplementary table 1:β2R affinities to agonist and antagonist in different rHDL.

Affinities (IC50) of agonist (Isoproterenol) and antagonist (Alprenolol) forβ2R reconstituted in rHDLs of different lipid compositions measured by competition against [3H]-dihydroalprenolol. Values represent means ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

Supplementary Table 2: Lipids bound to purifiedβ2R determined by mass spectrometry.

Lipids from Sf9 membranes and Sf9 purifiedβ2R were identified and quantified using rapid resolution liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Relative percentage of each type of phospholipid and cholesterol is represented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. Enrichment of each lipid is calculated as the ratio of the percentage of the given lipid bound to receptor in relation to the percentage of the lipid found in Sf9 membranes.

Supplementary Table 3: Specific enrichment of phosphatidylglycerol species on theβ2R.

Phosphatidylglycerol species found with purifiedβ2R were identified and quantified in lipids mixes from Sf9 membranes and from lipids extracted from Sf9 purifiedβ2R as in supplementary table 2. Relative percentage of each phosphatydilglycerol species is represented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. Enrichment of each species on theβ2R relative to their specific abundance in Sf9 membranes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rouslan Efremov for assistance with electron microscopy, Els Pardon & Jan Steyaert for providing purified Nb80, Aashish Manglik and Daniel Hilger for help with receptor production, Leonardo Pardo for help with the statistical tests, Roger Sunahara for providing the apoA1 plasmid and J-M Ruysschaert for helpful discussions. We acknowledge support from the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique F.R.S.-F.N.R.S. (grants F.4523.12, 34553.08 and T.0136.13) and a grant from the “Fond Extraordinaire de Recherche” (FER) 2007 of ULB. C. D. is a postdoctoral of the FRS-FNRS. C.G. is a Chercheur Qualifié of the FRS-FNRS and a WELBIO investigator. M.M. was supported by a Hoover Foundation Brussels Fellowship from the BAEF and AHA Award 15POST22700020.

Footnotes

Author Contributions R.D. expressed and purified the receptor, performed all HDL reconstitutions and functional characterizations, with the assistance of C.T. R.D. also performed all mass spectrometry analysis. M.M. also expressed and purified receptor samples. C.D. and P.V.A. performed mass spectrometry experiments. C.G. and B.K.K. provided overall project supervision and wrote the paper together with RD.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee AG. Biological membranes: the importance of molecular detail. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011;36:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gourdon P, et al. HiLiDe: Systematic Approach to Membrane Protein Crystallization in Lipid and Detergent. Crystal Growth & Design. 2011;11:2098–2106. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee AG. How lipids affect the activities of integral membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1666:62–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laganowsky A, et al. Membrane proteins bind lipids selectively to modulate their structure and function. Nature. 2014;510:172–175. doi: 10.1038/nature13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunte C, Richers S. Lipids and membrane protein structures. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:406–411. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koshy C, et al. Structural evidence for functional lipid interactions in the betaine transporter BetP. EMBO J. 2013;32:3096–3105. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long SB, Tao X, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature. 2007;450:376–382. doi: 10.1038/nature06265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan L, Smirnova IN, Verner G, Nagamori S, Kaback HR. Manipulating phospholipids for crystallization of a membrane transport protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:1723–1726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510922103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oates J, Watts A. Uncovering the intimate relationship between lipids, cholesterol and GPCR activation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011;21:802–807. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ostrom RS, Insel PA. The evolving role of lipid rafts and caveolae in G protein-coupled receptor signaling: implications for molecular pharmacology. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004;143:235–245. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang P, et al. Cholesterol reduction by methyl-beta-cyclodextrin attenuates the delta opioid receptor-mediated signaling in neuronal cells but enhances it in non-neuronal cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007;73:534–549. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albert AD, Young JE, Yeagle PL. Rhodopsin-cholesterol interactions in bovine rod outer segment disk membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1285:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(96)00145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gimpl G, Fahrenholz F. Cholesterol as stabilizer of the oxytocin receptor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1564:384–392. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00475-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pucadyil TJ, Chattopadhyay A. Cholesterol modulates ligand binding and G-protein coupling to serotonin(1A) receptors from bovine hippocampus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1663:188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oates J, et al. The role of cholesterol on the activity and stability of neurotensin receptor 1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:2228–2233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherezov V, et al. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson MA, et al. A specific cholesterol binding site is established by the 2.8 A structure of the human beta2-adrenergic receptor. Structure. 2008;16:897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell DC, Straume M, Miller JL, Litman BJ. Modulation of metarhodopsin formation by cholesterol-induced ordering of bilayer lipids. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9143–9149. doi: 10.1021/bi00491a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Botelho AV, Huber T, Sakmar TP, Brown MF. Curvature and hydrophobic forces drive oligomerization and modulate activity of rhodopsin in membranes. Biophys. J. 2006;91:4464–4477. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Botelho AV, Gibson NJ, Thurmond RL, Wang Y, Brown MF. Conformational energetics of rhodopsin modulated by nonlamellar-forming lipids. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6354–6368. doi: 10.1021/bi011995g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown MF. Curvature forces in membrane lipid-protein interactions. Biochemistry. 2012;51:9782–9795. doi: 10.1021/bi301332v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soubias O, Teague WE, Jr., Hines KG, Mitchell DC, Gawrisch K. Contribution of membrane elastic energy to rhodopsin function. Biophys. J. 2010;99:817–824. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soubias O, Teague WE, Gawrisch K. Evidence for specificity in lipid-rhodopsin interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:33233–33241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jastrzebska B, Goc A, Golczak M, Palczewski K. Phospholipids are needed for the proper formation, stability, and function of the photoactivated rhodopsin-transducin complex. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5159–5170. doi: 10.1021/bi900284x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inagaki S, et al. Modulation of the interaction between neurotensin receptor NTS1 and Gq protein by lipid. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;417:95–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whorton MR, et al. A monomeric G protein-coupled receptor isolated in a high-density lipoprotein particle efficiently activates its G protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:7682–7687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611448104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen SG, et al. Crystal structure of the beta2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature. 2011;477:549–555. doi: 10.1038/nature10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao XJ, et al. The effect of ligand efficacy on the formation and stability of a GPCR-G protein complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:9501–9506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811437106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasmussen SG, et al. Structure of a nanobody-stabilized active state of the beta(2) adrenoceptor. Nature. 2011;469:175–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuler MA, Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Nanodiscs as a new tool to examine lipid-protein interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;974:415–433. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-275-9_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nygaard R, et al. The dynamic process of beta(2)-adrenergic receptor activation. Cell. 2013;152:532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manglik A, et al. Structural Insights into the Dynamic Process of beta2-Adrenergic Receptor Signaling. Cell. 2015;161:1101–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsukamoto H, Sinha A, DeWitt M, Farrens DL. Monomeric rhodopsin is the minimal functional unit required for arrestin binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;399:501–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fliesler SJ, Anderson RE. Chemistry and metabolism of lipids in the vertebrate retina. Prog. Lipid Res. 1983;22:79–131. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(83)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whorton MR, et al. Efficient coupling of transducin to monomeric rhodopsin in a phospholipid bilayer. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:4387–4394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703346200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsukamoto H, Szundi I, Lewis JW, Farrens DL, Kliger DS. Rhodopsin in nanodiscs has native membrane-like photointermediates. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5086–5091. doi: 10.1021/bi200391a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kenakin T. Drug efficacy at G protein-coupled receptors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;42:349–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.091401.113012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Granier S, et al. Structure and conformational changes in the C-terminal domain of the beta2-adrenoceptor: insights from fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:13895–13905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Velez-Ruiz GA, Sunahara RK. Reconstitution of G protein-coupled receptors into a model bilayer system: reconstituted high-density lipoprotein particles. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;756:167–182. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-160-4_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1:Size-exclusion of β2R rHDLs of different lipidic compositions

Size-exclusion chromatography profiles of the various rHDL using a Superdex 200/300GL column (GE Healthcare) showing one major peak in all cases. The main peak was collected for subsequent functional assays.

Supplementary Figure 2: Homogeneity and particle size analysis ofβ2R rHDLs in different lipidic compositions.

Transmission electron micrographs for negatively stained rHDLs of different lipid compositions. Defined homogeneous particles of 9-12.5 nm depending on the lipid used were observed. Particle sizes in each environment were measured and mean diameter ± SEM in nm is shown in the table.

Supplementary Figure 3: Solubilized lipids do not form bilayer

Transmission electron micrographs for negatively stained samples ofβ2R + solubilized DOPG (1μMβ2R, 200μM DOPG, 500μM DDM and 600 μM sodium cholate), showing particle size of about 8 nm, as expected for receptor/detergent micelles. No liposome was observed.

Supplementary table 1:β2R affinities to agonist and antagonist in different rHDL.

Affinities (IC50) of agonist (Isoproterenol) and antagonist (Alprenolol) forβ2R reconstituted in rHDLs of different lipid compositions measured by competition against [3H]-dihydroalprenolol. Values represent means ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

Supplementary Table 2: Lipids bound to purifiedβ2R determined by mass spectrometry.

Lipids from Sf9 membranes and Sf9 purifiedβ2R were identified and quantified using rapid resolution liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Relative percentage of each type of phospholipid and cholesterol is represented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. Enrichment of each lipid is calculated as the ratio of the percentage of the given lipid bound to receptor in relation to the percentage of the lipid found in Sf9 membranes.

Supplementary Table 3: Specific enrichment of phosphatidylglycerol species on theβ2R.

Phosphatidylglycerol species found with purifiedβ2R were identified and quantified in lipids mixes from Sf9 membranes and from lipids extracted from Sf9 purifiedβ2R as in supplementary table 2. Relative percentage of each phosphatydilglycerol species is represented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. Enrichment of each species on theβ2R relative to their specific abundance in Sf9 membranes.