A nationwide survey of physicians in Japan was conducted to determine factors that influence when they held end-of-life discussions with their patients with advanced cancer. Experience with and beliefs regarding end-of-life discussions, as well as physicians’ own perceptions of what constitutes a good death, significantly contributed to these discussions being held at the time of diagnosis.

Keywords: Oncologist, End-of-life discussion, Attitude, Hospice, Do-not-resuscitate

Abstract

Background.

End-of-life discussions (EOLds) occur infrequently until cancer patients become terminally ill.

Methods.

To identify factors associated with the timing of EOLds, we conducted a nationwide survey of 864 medical oncologists. We surveyed the timing of EOLds held with advanced cancer patients regarding prognosis, hospice, site of death, and do-not-resuscitate (DNR) status; and we surveyed physicians’ experience of EOLds, perceptions of a good death, and beliefs regarding these issues. Multivariate analyses identified determinants of early discussions.

Results.

Among 490 physicians (response rate: 57%), 165 (34%), 65 (14%), 47 (9.8%), and 20 (4.2%) would discuss prognosis, hospice, site of death, and DNR status, respectively, “now” (i.e., at diagnosis) with a hypothetical patient with newly diagnosed metastatic cancer. In multivariate analyses, determinants of discussing prognosis “now” included the physician perceiving greater importance of autonomy in experiencing a good death (odds ratio [OR]: 1.34; p = .014), less perceived difficulty estimating the prognosis (OR: 0.77; p = .012), and being a hematologist (OR: 1.68; p = .016). Determinants of discussing hospice “now” included the physician perceiving greater importance of life completion in experiencing a good death (OR: 1.58; p = .018), less discomfort talking about death (OR: 0.67; p = .002), and no responsibility as treating physician at end of life (OR: 1.94; p = .031). Determinants of discussing site of death “now” included the physician perceiving greater importance of life completion in experiencing a good death (OR: 1.83; p = .008) and less discomfort talking about death (OR: 0.74; p = .034). The determinant of discussing DNR status “now” was less discomfort talking about death (OR: 0.49; p = .003).

Conclusion.

Reflection by oncologists on their own values regarding a good death, knowledge about validated prognostic measures, and learning skills to manage discomfort talking about death is helpful for oncologists to perform appropriate EOLds.

Implications for Practice:

Oncologists’ own perceptions about what is important for a “good death,” perceived difficulty in estimating the prognosis, and discomfort in talking about death influence their attitudes toward end-of-life discussions. Reflection on their own values regarding a good death, knowledge about validated prognostic measures, and learning skills to manage discomfort talking about death are important for improving oncologists’ skills in facilitating end-of-life discussions.

Introduction

Having timely end-of-life discussions (EOLds) with advanced cancer patients is essential; multiple empirical studies demonstrate that EOLds reduce unnecessary aggressive care near death, provide end-of-life (EOL) care consistent with patients’ preferences, increase early hospice referrals, and improve patients’ quality of life [1–5]. Many physicians, however, do not actually discuss EOL options with advanced cancer patients until they are in the terminal phase of life [6, 7]. This delay could be a result of both patient- and physician-related factors [1].

Understanding physician-related factors associated with the timing of EOLds will help obtain insights on how the oncology community may further improve EOLds. Existing literature has identified a variety of factors contributing to physician attitudes toward EOLds [8–16]; a study by Keating et al. showed that a physician’s background (i.e., age, specialty, and practice site) was significantly correlated with the timing of discussions about prognosis, hospice enrollment, the preferred site of death, and do-not-resuscitate (DNR) status [6]. Based on these findings, a recent review proposed a conceptual framework of physician factors associated with their attitudes toward EOLds, including lack of communication training, discomfort in discussing EOL issues, time constraints, and difficulties in prognostication [1]. Few studies, however, to our best knowledge, have systematically evaluated factors associated with physician attitude toward EOLds, especially whether oncologists’ own experience, perception, and beliefs about EOL influence the timing of EOLds [1].

The primary aim of this study was to systemically explore oncologist factors (i.e., experience of EOLds, factors physicians perceive as influencing a good death, and beliefs regarding EOLds) contributing to the timing of discussing EOL issues with advanced cancer patients. Our main interest was to clarify the relative importance of multiple oncologists’ factors in determining the timing of EOLds.

Materials and Methods

This was a nationwide, cross-sectional survey. We distributed questionnaires to medical oncologists in Japan. The questionnaires were distributed by mail in January 2014, with a reminder sent 1 month later.

Subjects and Procedure

All medical oncologists certified by the Japanese Society of Medical Oncology who worked at designated cancer hospitals in Japan were recruited. The Japanese Society of Medical Oncology is the only approved organization that issues certification of medical oncologists. Physicians’ names and affiliations were obtained from the website of the Society. Responses were considered consent to participate. No reward was provided. Responses to the questionnaire were voluntary, and confidentiality was maintained throughout all investigations and analyses. No identification numbers were linked with the original data. The study was exempt from review by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Center Hospital, based on the national ethical guideline of epidemiological studies.

Measurements

Endpoint

The study endpoint was oncologists’ attitudes toward the timing of discussing EOL issues. We used the same questions as those in the Keating et al. study [6]. We asked participants, “Assume you are caring for a patient who has been newly diagnosed with metastatic cancer, but is currently feeling well. When, in the course of the typical patient’s illness, are you most likely, for the first time, to discuss the following with this patient or his/her family: (a) the prognosis, (b) hospice enrollment, (c) the preferred site of death, and (d) DNR status?” Response options were “now (at diagnosis of a metastatic cancer),” “when the patient first has symptoms,” “when there are no more nonpalliative treatments,” “only if the patient is hospitalized,” “only if the patient and/or family brings it up,” and “never explain.” After a pilot test, we decided to add “never explain” as a response option to better reflect clinical practice in Japan. For clarification, we also specified that the patient was 40 years old and had an estimated survival of 2–3 years.

We had acknowledged that having an EOLd at the time of diagnosis was not always appropriate for all patients, and that the response options were not mutually exclusive; we had decided, however, to use the timing of the first discussion of the EOL issues as the primary endpoint, consistent with the Keating et al. study [6]. This was on the basis of the hypothesis that distribution of the timing would demonstrate the overall tendency of oncologists toward timing of EOLds and comparability with previous findings [6].

Potential Factors Contributing to Oncologists’ Attitudes Toward EOLds

Potential factors contributing to the endpoint included demographic data, oncologists’ experience of EOLds, the physician’s perception of what constituted a good death, and beliefs regarding EOLds. These measurements were developed based on a systematic literature review [1, 6–16], discussions among research groups, and preliminary in-depth interviews with medical oncologists. Face validity was confirmed by pilot testing.

Demographic Data

Oncologists’ characteristics investigated included age, sex, specialty, institution, clinical experience, number of cancer patients seen in past year, responsibility as treating physician at EOL, and region.

Experience of EOLd

To explore oncologists’ experience of EOLds, we presented participants with 4 statements to rate the frequency of their clinical experience on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very frequently). The statements were as follows: marked anxiety of patients caused by an EOLd, marked anxiety of families caused by an EOLd, patients spend terminal phase as desired because of EOLds, and experience of patients attempting/committing suicide just after an EOLd. Because of their high internal consistency, we combined the first two statements into “marked anxiety of patients/families caused by EOLd” (α = 0.76) and calculated subscale scores by averaging individual item scores. Each score, therefore, ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher levels of agreement for each subscale or item. Based on the actual distributions of the responses, we divided responses to the last statement (experience of patients attempting/committing suicide just after an EOLd) into “never” and “others.”

Physician-Perceived Good Death

To explore physicians’ perceptions of factors influencing a good death, we adopted a conceptual framework based on previous studies on good death [17–19]. We asked participants how important they perceived each element to be for terminally ill patients on a 6-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not important at all) to 6 (essential). We determined 4 concepts to be investigated: autonomy (3 items; α = 0.73), life completion (3 items; α = 0.83), physical comfort, and dying in the preferred place (1 item for each). For domains with multiple items, the score was defined as the mean of item scores; thus, higher scores indicate a higher physician-perceived importance of the domain. These measures have been used in previous surveys with interpretable findings, although a formal validation test was not performed [18, 19]. The actual questions are listed in supplemental online Table 1.

Beliefs Regarding EOLds

We asked participants to rate 17 statements on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We performed exploratory factor analysis to identify the underlying structure of beliefs regarding EOLds, and we calculated Cronbach α coefficients for each factor. The subscales of the underlying structure included the following: “difficulty estimating prognosis” (1 item); “discomfort talking about death” (1 item); “severely distressing for patients and families” (4 items; α = 0.77); “lack of sufficient time” (1 item); “lack of education on EOLd” (2 items; α = 0.64); “negative general image of hospices and palliative care” (1 item); “availability of other health-care professionals” (5 items; α = 0.83); “perception of EOLd as failure of medicine” (1 item); and “perception of physician’s role as sustaining patient’s life” (1 item). For a subscale with multiple items, we defined the score as the mean of item scores. Each subscale score, therefore, ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher levels of agreement for each subscale factor. The actual statements are listed in supplemental online Table 2.

Statistical Analysis

For comparisons, responses regarding physicians’ attitudes toward EOLds were divided into two categories (“now” vs. other responses). To explore the potential association between the factors scored by oncologists and the timing of EOLds, logistic univariate regression analyses were performed to screen the use of demographics, experience of EOLds, physicians’ perception of a good death, and beliefs regarding EOLds as independent variables, and the use of the timing of EOLds as a dependent variable. Last, to identify independent determinants of having an EOLd at diagnosis, all factors with a p value of <.1 identified in univariate analyses were entered into multivariate logistic regression analysis.

In all statistical evaluations, p values of ≤.05 were considered significant for the exploratory nature of the study. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 22.0 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, http://www-01.ibm.com/).

Results

Participants’ Characteristics

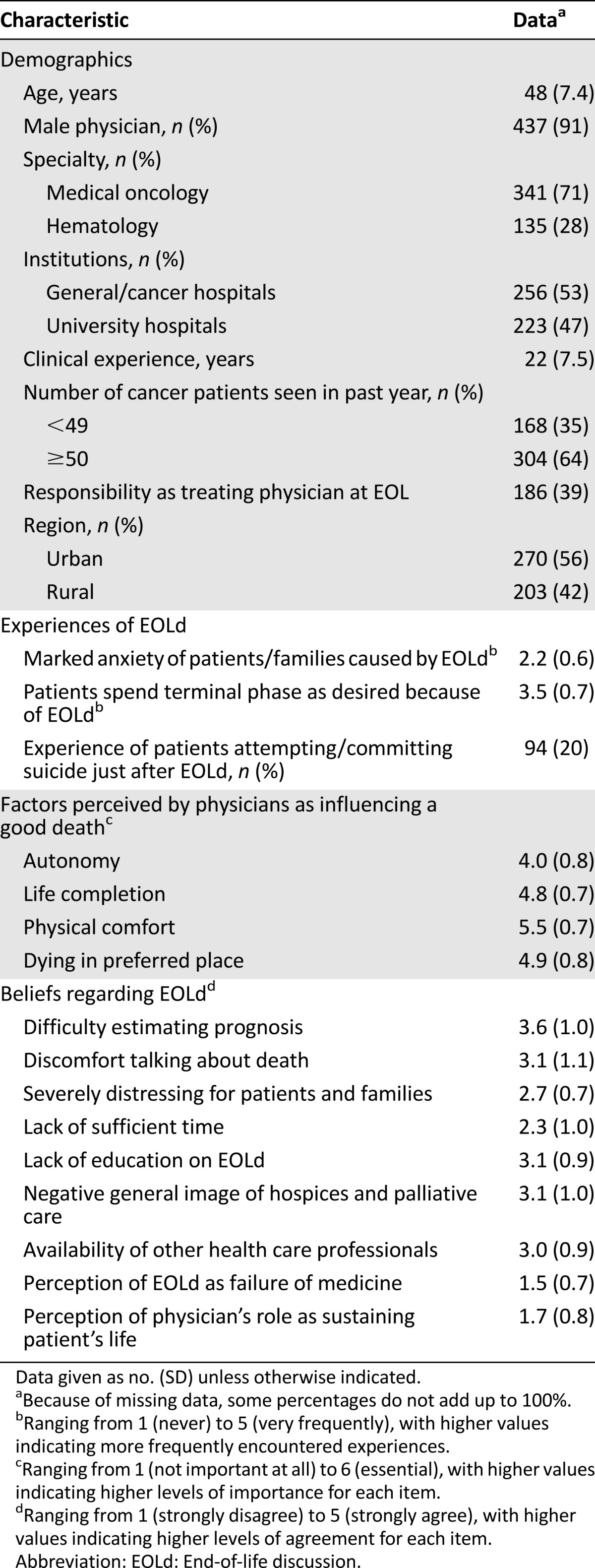

Among the 864 participants who were provided with the questionnaire, 490 responded (response rate: 57%). We further excluded 11 physicians who were neither medical oncologists nor hematologists (surgeons, n = 4; radiation oncologists, n = 4; urologist, n = 1; radiologist, n = 1; physician translational researcher, n = 1). The characteristics of a total of 479 physicians (effective response rate, 55%) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participating physicians (n = 479)

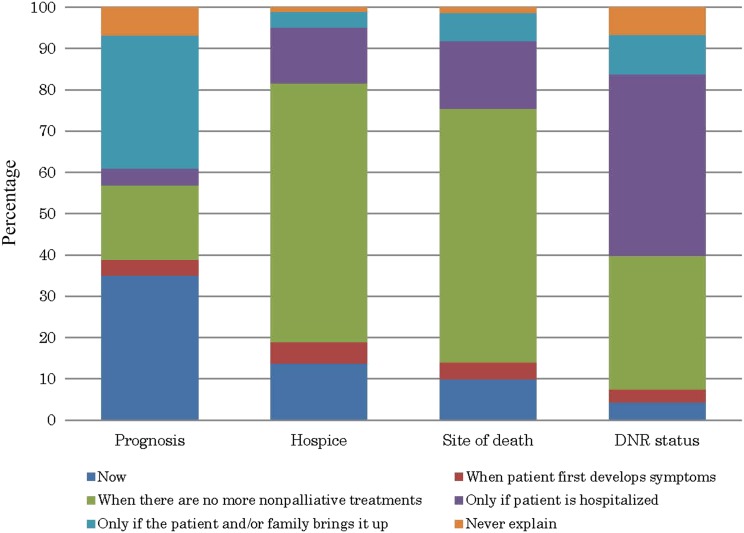

Attitudes Toward EOLd

Figure 1 presents participants’ reports of when they would discuss the prognosis, hospice enrollment, the preferred site of death, and DNR status with their advanced cancer patients. The most frequent timing of EOLds for prognosis was “now” (i.e., at diagnosis of a metastatic cancer) (34%; n = 165) and “only if the patient and/or family brings it up” (32%; n = 152); followed by hospice and site of death, when there are no more nonpalliative treatments (62% [n = 298]; and 61% [n = 290], respectively); and DNR status, when patient is hospitalized (43%; n = 207).

Figure 1.

Bar graph of oncologists’ reports of when they would discuss the prognosis, hospice enrollment, the preferred site of death, and DNR status with a patient newly diagnosed with metastatic cancer.

Abbreviation: DNR, do-not-resuscitate.

Factors Contributing to Attitudes Toward EOLd

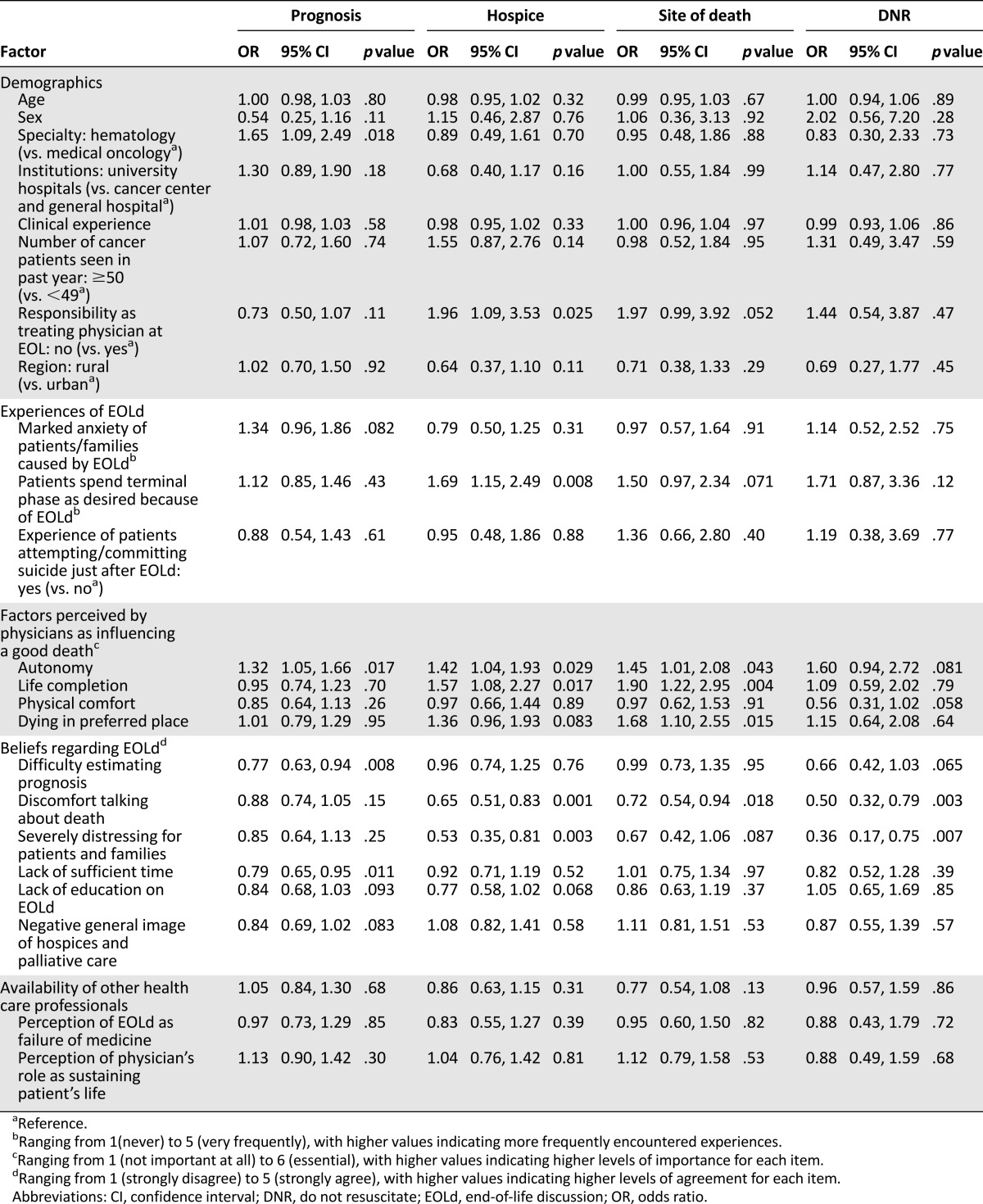

The results of univariate analyses are summarized in Table 2. Participants’ attitude toward discussing the prognosis “now” was significantly correlated with being a hematologist, and the physician perceiving greater importance of autonomy to experience a good death, less difficulty in estimating the prognosis, and not perceiving that there is insufficient time to discuss the patient’s prognosis. The attitude toward discussing hospice enrollment “now” was significantly correlated with no responsibility as a treating physician at EOL, more experience with patients spending their terminal phase as they desired because of an EOLd, the physician perceiving greater importance of autonomy and life completion to experience a good death, less discomfort talking about death, and not perceiving EOLds as being severely distressing for patients and families. Attitude toward discussing the preferred site of death “now” was significantly correlated with the physician perceiving greater importance of autonomy, life completion, and dying in the preferred place to experience a good death, and less discomfort in talking about death. The attitude toward discussing the DNR status “now” was significantly correlated with less discomfort talking about death and not perceiving EOLds as being severely distressing for patients and families.

Table 2.

Factors predicting physicians discussing the prognosis, hospice enrollment, the site of death, and DNR status with patients “now” (at diagnosis of a metastatic cancer): univariate analyses

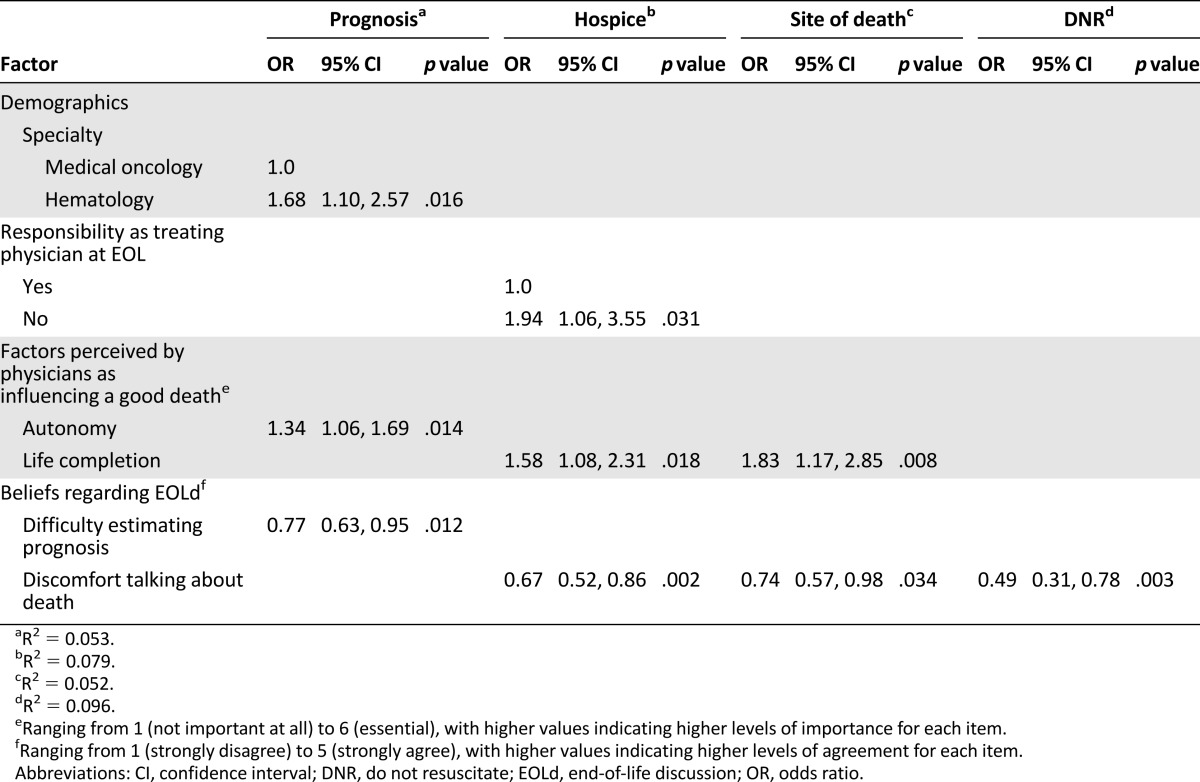

Multivariate Analyses

The results of multivariate analyses are summarized in Table 3. Independent determinants of the attitude toward discussing the prognosis “now” included being a hematologist, and the physician perceiving greater importance of autonomy to experience a good death and less difficulty estimating the prognosis. Independent determinants of the attitude toward discussing hospice enrollment “now” included no responsibility as the treating physician at EOL, the physician perceiving greater importance of life completion to experience a good death, and less discomfort talking about death. Independent determinants of the attitude toward discussing the preferred site of death “now” included the physician perceiving greater importance of life completion to experience a good death and less discomfort talking about death. Last, the only independent determinant of the attitude toward discussing the DNR status “now” was less discomfort talking about death.

Table 3.

Factors predicting physicians discussing the prognosis, hospice enrollment, the site of death, and DNR status with their patients “now” (at diagnosis of a metastatic cancer): multivariate analyses

Discussion

This nationwide survey is one of few studies to systematically identify oncologists’ factors contributing to the timing of EOLds, especially their experience with EOLds, the physician’s perception of a good death, and beliefs regarding EOLds. Our results suggest multiple promising strategies to help oncologists discuss end-of-life issues in an earlier phase of a metastatic cancer.

One of the important findings was that oncologists who felt discomfort talking about death were more likely to discuss hospice enrollment, the preferred site of death, and DNR status at a later time. This was supported by prior studies showing that physicians’ discomfort, difficulty, and burden about talking about death and dying are strong barriers for EOLds [1, 11, 13–16, 20–24]. Physicians engaged in EOL care can have a high level of burnout and psychiatric morbidity; skills to manage discomfort when talking about death would be valuable for oncologists [22]. While recent randomized controlled trials revealed that training improved oncologists’ communication skills, patients’ mental health, and patients’ trust in oncologists [23, 24], little is known about how oncologists obtain skills to manage their own discomfort with talking about death. Examples of practical ways may include, but may not be limited to, talking with colleagues and/or senior medical oncologists who have confidence in communicating EOL issues, rotating palliative care services such as home hospice programs during the oncology fellowship, sharing personal experiences of patients and their families who have received hospice care and perceived cexperiencing a good death, and normalizing death and dying by engaging in nonmedical activities such as reading humanistic books on death. Future studies are strongly encouraged to establish effective strategies specifically focusing on skills to manage discomfort talking about death.

The second important finding was that oncologists who felt difficulty estimating the prognosis were more likely to discuss the prognosis later. While precise prognostic information enables patients and their families to make decisions and set goals and priorities, clinical prediction of survival is often inaccurate and overestimated [25]. Recent studies, however, confirmed that some scoring systems (i.e., Palliative Prognostic Score, Palliative Prognostic Index, and Prognosis in Palliative Care Study predictor models) are reliable tools for prognostic assessment of advanced cancer patients [25–27]. Knowledge about these prognostic measures may improve the accuracy of oncologists’ prognostications and thus facilitate earlier EOLds.

The third important finding was identification of the impact of oncologists’ own experience of EOLds and their perception about life completion as experiencing a good death. Oncologists who experienced patients spending their terminal phase as they desired because of an EOLd and those who valued life completion to experience a good death were more likely to discuss hospice enrollment and the preferred site of death earlier. This is supported by an observation that patients who died at home or in hospices had a better feeling about life completion compared with those who died in hospitals [5, 28]. The finding of our study indicates that some oncologists believe that early discussion about hospices and place of death could lead to life completion. Recognizing place of death as an important outcome of medicine and sharing positive experiences of EOLds about hospice and place of death may be helpful to facilitate EOLds.

This study also clarified oncologists’ experience and beliefs about EOLds. Of note was that 20% of oncologists experienced a patient attempting or committing suicide just after an EOLd. Cancer and disclosure of incurability can be risks for suicide [29, 30], and a further cohort study, especially of patients who received an EOLd, is required to clarify the potential effects of EOLds on patient suicide. This study revealed that oncologists who perceived an EOLd as a failure of medicine and the physician’s role in sustaining a patient’s life were in the minority (i.e., an average of less than a 2-point agreement on 1–5 Likert scale). Rather, agreements on the statements of difficulty estimating prognosis, lack of education on EOLds, and discomfort talking about death were scored higher (more than 3). These results indicate oncologists consider EOLds as one of their important tasks but feel strong conflicts in achieving quality EOLds. Multifaceted strategies suggested in this study are promising to improve practice of EOLds for both patients and oncologists.

Despite the strengths of the nationwide survey, this study had several limitations. First, the response rate was moderate (57%) and baseline characteristics of nonresponders were not available. We believe, however, that this limitation is acceptable because previous national surveys from U.S. and Japanese physicians also reported similar response rates [6, 18, 19]. Second, we performed no formal testing of the validity and reliability of some items of our questionnaire. We believe that this limitation does not severely limit the quality of our study, because established tools to measure physicians’ experiences of and beliefs regarding EOLds are not available, and we performed exploratory analyses and calculated the Cronbach α. Third, our findings were based on self-report instead of actual occurrences of EOLds. A prospective study on the EOLd experience of patients will be warranted to explore actual occurrences of discussions of various EOL issues. Fourth, our model explained only less than 10% of the variation and, thus, there must have been unmeasured factors. Future studies should include other variables such as participants’ mental health, religious background, availability of specialized palliative care services, and previous training in communication skills. Fifth, this is a vignette survey; thus, prospective studies are needed to capture physicians’ attitudes toward EOLds in real-world situations to confirm the results of this study. Finally, cultural differences might limit the generalizability of the findings. We believe, however, the findings of this study could be applied to other ethnic populations because the factors identified in literature are universally identical [1].

Conclusion

This large survey revealed that oncologists’ factors (i.e., experience of EOLd, physician’s perception of a good death, and beliefs regarding EOLds) significantly contributed to the timing of EOLds with advanced cancer patients. As practical ways to make positive outcomes through EOLds, we suggest that medical oncologists (a) be aware of their own personal attitudes, experiences, beliefs, and perceptions of EOLds through talking with colleagues or self-reflection; (b) make efforts not to impose their own values on the patient, but instead to ask and respect their patient’s goals, wishes, and preferences; (c) familiarize themselves with validated prognostic measures; and (d) introduce a multidisciplinary approach with or without early referral to a palliative care team to help facilitate this important communication process.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (25-B-5). This study was partially supported by the Mitsubishi Foundation and the Japan Hospice Palliative Care Foundation. The funding bodies were not involved in the conducting of the study or its submission.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Alicia K. Morgans, Lidia Schapira. Confronting Therapeutic Failure: A Conversation Guide. The Oncologist 2015;20:946-951.

Implications for Practice: Discussing the failure of anticancer therapy remains a very difficult conversation for oncologists and their patients. In this article, the process of confronting this failure is broken down into various components, and practical tips are provided for clinicians following a classic protocol for breaking bad news. Also addressed are the emotions of the oncologist and the reasons why these conversations are typically so hard. These insights are based on solid research intended to deepen the therapeutic connection between physician and patient.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Masanori Mori, Chikako Shimizu, Asao Ogawa, Takuji Okusaka, Saran Yoshida, Tatsuya Morita

Provision of study material or patients: Asao Ogawa

Collection and/or assembly of data: Chikako Shimizu

Data analysis and interpretation: Masanori Mori, Chikako Shimizu, Asao Ogawa, Tatsuya Morita

Manuscript writing: Masanori Mori, Chikako Shimizu, Asao Ogawa, Takuji Okusaka, Saran Yoshida, Tatsuya Morita

Final approval of manuscript: Masanori Mori, Chikako Shimizu, Asao Ogawa, Takuji Okusaka, Saran Yoshida, Tatsuya Morita

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, et al. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: Predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1203–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lundquist G, Rasmussen BH, Axelsson B. Information of imminent death or not: Does it make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3927–3931. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.6247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinoshita H, Maeda I, Morita T, et al. Place of death and the differences in patient quality of death and dying and caregiver burden. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:357–363. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.7355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO, Jr, et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end-of-life care. Cancer. 2010;116:998–1006. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levin TT, Li Y, Weiner JS, et al. How do-not-resuscitate orders are utilized in cancer patients: Timing relative to death and communication-training implications. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6:341–348. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markson L, Clark J, Glantz L, et al. The doctor’s role in discussing advance preferences for end-of-life care: Perceptions of physicians practicing in the VA. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley EH, Cicchetti DV, Fried TR, et al. Attitudes about care at the end of life among clinicians: A quick, reliable, and valid assessment instrument. J Palliat Care. 2000;16:6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruhnke GW, Wilson SR, Akamatsu T, et al. Ethical decision making and patient autonomy: a comparison of physicians and patients in Japan and the United States. Chest. 2000;118:1172–1182. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.4.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reilly BM, Magnussen CR, Ross J, et al. Can we talk? Inpatient discussions about advance directives in a community hospital. Attending physicians’ attitudes, their inpatients’ wishes, and reported experience. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2299–2308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mebane EW, Oman RF, Kroonen LT, et al. The influence of physician race, age, and gender on physician attitudes toward advance care directives and preferences for end-of-life decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:579–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granek L, Krzyzanowska MK, Tozer R, et al. Oncologists’ strategies and barriers to effective communication about the end of life. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:e129–e135. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otani H, Morita T, Esaki T, et al. Burden on oncologists when communicating the discontinuation of anticancer treatment. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:999–1006. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyr092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell ES, et al. Why don’t patients and physicians talk about end-of-life care? Barriers to communication for patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and their primary care clinicians. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1690–1696. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baile WF, Lenzi R, Parker PA, et al. Oncologists’ attitudes toward and practices in giving bad news: An exploratory study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2189–2196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyashita M, Sanjo M, Morita T, et al. Good death in cancer care: A nationwide quantitative study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1090–1097. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimada A, Mori I, Maeda I, et al. Physicians’ attitude toward recurrent hypercalcemia in terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:177–183. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morita T, Oyama Y, Cheng SY, et al. Palliative care physicians’ attitude toward patient autonomy and good death in East-Asian countries. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;2:190–199.el. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley EH, Cramer LD, Bogardus ST, Jr, et al. Physicians’ ratings of their knowledge, attitudes, and end-of-life-care practices. Acad Med. 2002;77:305–311. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al. Communicating prognosis in cancer care: A systematic review of the literature. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1005–1053. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whippen DA, Canellos GP. Burnout syndrome in the practice of oncology: Results of a random survey of 1,000 oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1916–1920. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.10.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Asai M, et al. Effect of communication skills training program for oncologists based on patient preferences for communication when receiving bad news: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2166–2172. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goelz T, Wuensch A, Stubenrauch S, et al. Specific training program improves oncologists’ palliative care communication skills in a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3402–3407. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.6372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maltoni M, Caraceni A, Brunelli C, et al. Prognostic factors in advanced cancer patients: Evidence-based clinical recommendations--a study by the Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6240–6248. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Pittureri C, et al. Prospective comparison of prognostic scores in palliative care cancer populations. The Oncologist. 2012;17:446–454. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gwilliam B, Keeley V, Todd C, et al. Development of prognosis in palliative care study (PiPS) predictor models to improve prognostication in advanced cancer: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343:d4920. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. Place of death: Correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4457–4464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu D, Fall K, Sparén P, et al. Suicide and suicide attempt after a cancer diagnosis among young individuals. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:3112–3117. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamauchi T, Inagaki M, Yonemoto N, et al. Death by suicide and other externally caused injuries following a cancer diagnosis: The Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Psychooncology. 2014;23:1034–1041. doi: 10.1002/pon.3529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.