Abstract

Over the last decade there has been a bottleneck in the introduction of new validated cancer metabolic biomarkers into clinical practice. Unfortunately, there are no biomarkers with adequate sensitivity for the early detection of cancer, and there remain a reliance on cancer antigens for monitoring treatment. The need for new diagnostics has led to the exploration of untargeted metabolomics for discovery of early biomarkers of specific cancers and targeted metabolomics to elucidate mechanistic aspects of tumor progression. The successful translation of such strategies to the treatment of cancer would allow earlier intervention to improve survival. We have reviewed the methodology that is being used to achieve these goals together with recent advances in implementing translational metabolomics in cancer.

Keywords: cancer, cancer diagnosis, diagnostic biomarkers, lipidomics, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, NMR spectroscopy, prognostic biomarkers, untargeted metabolomics targeted metabolomics

Metabolomics has been defined as the study of “the complete set of metabolites, which are context dependent, varying according to the physiology, developmental or pathological state of the cell, tissue or organism” [1]. However, metabolomics studies cannot possibly meet this lofty goal because of the large number of small molecule lipid metabolites that can potentially exist. Examination of lipid structures suggest that there are likely to be >100,000 possible esterified lipid molecules. Probably for this reason, most studies have tended to focus primarily on non-esterified lipids and on higher abundance low-molecular-weight metabolites that can be analyzed by GC-MS [2]. The field of lipidomics has evolved to fill this gap and lower abundance metabolites are analyzed in more specialized assays such as those described for estrogens [3]. Cancer metabolic studies are generally conducted using either NMR spectroscopy or LC-MS using three major approaches: first, untargeted LC-MS methods to profile metabolites in order to discover those that are dysregulated using sophisticated software packages to reveal differences in the chromatographic profiles [4–7]. Characterizing the differentially regulated metabolites that are found remains a major challenge. Second, quantitative NMR or LC-MS studies of metabolites from particular metabolic pathways [1,6,8,9]. This requires appropriate validation and quality control samples to provide adequate rigor [10]. Third, NMR- or LC-MS-based isotopomer analyses targeted to specific metabolic pathways using stable isotope labeled precursors [11,12]. Unfortunately, these studies have been primarily restricted to cell culture and tissue samples from animal models. Some progress has been made in developing surrogate tissues such as blood platelets for conducting isotopomer studies in humans [13]. However, this methodology has not yet been tested in cancer patients.

In spite of a huge number of metabolomics-based studies, over the last decade, little progress has been made in introducing new cancer biomarkers into clinical practice. This means that there still is a heavy reliance on carbohydrate antigens (CA) for monitoring the treatment of many cancers such as CA 125 for ovarian cancer and CA 19–9 for pancreatic cancer. Fortunately, metabolic biomarker discovery and validation is an incredibly active area of research and there are a number of candidate biomarkers undergoing validation studies. Unfortunately, there are still no biomarkers with adequate sensitivity for the early detection of any cancers, which contributes to making this disease very difficult to treat. There is hope that the untargeted metabolomics and lipidomics methodology will lead to the discovery of early biomarkers of specific cancers. This would allow the treatment of specific cancers to be initiated at a much earlier stage and improve overall survival. Early detection is particularly relevant to pancreatic cancer, which takes some 15 years to develop and results in a very poor prognosis after the cancer is detected. One-year survival rates from pancreatic cancer are <5%; whereas in contrast, survival rates of >40% were observed when pancreatic cancer was identified early from CT scans conducted for other reasons (such as after car crashes). There is also emerging evidence that early detection of lung cancer from CT scanning can lead to improved survival, although a large number of false positives and false negatives were observed. Metabolomics or lipidomic biomarkers could potentially help eliminate the false negatives and false positives that have been found in these studies. Therefore, in principle, validated serum metabolomic or lipidomic biomarkers could further improve survival and help avoid unnecessary invasive procedures.

Metabolomics methodology in cancer research

A metabolomics approach will include steps of sample collection, sample preparation, spectral acquisition and data analysis, followed by iterative steps of validation. Although this workflow resembles approaches of proteomics and genomics, the variation in the properties of diverse metabolites versus the comparatively uniform properties of proteins, RNA and DNA, require an attention to rigor not yet achieved uniformly in the field. As an –omics methodology, metabolomics has great promise with equally great barriers and has already uncovered controversial findings across disease states. Metabolomics offers a target rich environment in oncology since extensive metabolic reprogramming is observed in cancer cells as highlighted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells.

In cancer cells an increased uptake of glucose occurs as well as diversion of glycolytic intermediates to biosynthetic pathways including nucleosides, amino acids and lipids, which support cell growth and proliferation. Up and down arrows indicate cancer-associated upregulation/activation or downregulation/inhibition of enzymes. Alterations in red can be caused by the activation of HIF-1.

CA9 and 12: Carbonic anhydrase 9 and 12; CPT: Carnitine palmitoyltransferase; GLUT: Glucose transporter: GSH: Glutathione; HIF: Hypoxia inducible factor: IDO: Indoleamine, 2,3,-dioxygenase: HK: Hexokinase; LAT1: L-type amino acid transporter: LDHA: Lactate dehydrogenase isoform A; MCT: Monocarboxylate transporter; OXPHOS: Oxidative phosphorylation; PDH: Pyruvate dehydrogenase; PDK: Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; PFK: Phosphofructokinase; P13K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PGM: Phosphoglycerate mutase; PKM2: Pyruvate kinase isoform M2; PPP: Pentose phosphate pathway; SCO2: Synthesis of cytochrome c oxidase 2; TLK: Transketolase; VDAC: Voltage-dependent anion channel.

Reproduced with permission from [35] © Elsevier.

Broadly, methodological approaches to metabolomics can be categorized as either targeted or untargeted. Targeted approaches measure a defined number of analytes, and maximize sensitivity and specificity toward those analytes. Untargeted approaches aim to capture the greatest number of metabolites, and trade sensitivity and specificity for wide metabolic coverage. Targeting can be imposed by experimental design, and influenced by collection, extraction, sample analysis and data analysis. A mixed approach, including both targeted and untargeted analysis in the same run, is possible depending on platform and workflow. Other metabolomics approaches may utilize stable isotope tracers to measure isotopic labeling or by increasing signal to noise ratios [12]. A priori knowledge of the chemical space in the sample can greatly influence design and workflow, and can reduce the problem of multivariable optimization in experimental design.

Sample collection is critical to metabolomics. A wide variety of biological specimens have been used for metabolomics studies including urine, feces, tissues, blood, saliva sputum, seminal fluid, synovial fluid, cerebrospinal fluid and exhaled breath condensate [14]. For example, this has resulted in the discovery of volatile organic compounds in exhaled breath condensate as candidate biomarkers for esophageal-gastric cancers [15]. The influences of diet, circadian rhythm, xenobiotic exposure, collection technique and a host of other variables will introduce variation or possibly systematic bias into a metabolomics experiment. Matched samples, such as pre-/post-treatment can reduce individual variation, but introduce other temporally related bias. Attention should be paid to proper collection including quenching of ongoing metabolism and storage of samples.

Sample preparation often removes the chemicals of interest from a complex matrix. ‘Cleaning’ the sample through extraction can increase sensitivity, specificity and robustness. Extraction processes may be as simple as filtration and protein removal or as complex as multistep orthogonal workflows. The dramatic effect of protein removal can be seen on NMR spectra before and after protein removal in Figure 2. However, extreme care should be taken in extraction because even seemingly simple protein removal can systematically bias the experiment through unequal removal of protein binding analytes. Chemical and physical properties such as aqueous/organic partition, pH, redox state, salt and counterion pairing, protein binding or chemical instability can influence extracted metabolites. Extractions may incorporate different amounts of automation and be off-line of analysis, on-line or a mix of both.

Figure 2. A 500 MHz 1H NMR spectrum of blood plasma sample: (A) before and (B) after protein removal.

Reproduced with permission from [9].

Spectral acquisition by NMR and mass spectrometry (MS) will primarily be covered in the next two sections. Analysis can be multidimensional and multiplatform to increase coverage and/or overlap. It is worth noting that sample analysis need not be only by these two methods, but could include other modes of detection such as UV-Vis, radiographic or fluorescent. However, the capabilities of NMR and MS have made these two platforms the almost universally preferred methods for modern metabolomics.

Data analysis in metabolomics has an ever expanding requirement to deal with an equally expanding set of data points. Powerful bioinformatics platforms incorporating adaptive binning, peak alignment, peak fitting, multidimensional analysis, correlation and pattern finding capabilities and/or database integration are constantly being developed and improved. Broadly, data analysis can be organized into a workflow of feature detection, quantitation, pattern recognition and metabolite identification. Feature detection relies on defining windows within a dimension of analysis (binning) or fitting a predefined algorithm to the data (peak finding) [8]. A basic illustration of these approaches can be found in Figure 3. Detection of features may also include alignment of the spectra or background/noise subtraction. Features may also be annotated for relation to each other, such as where multiple peaks correspond to the same molecule. An important criterion of feature detection is that it directly impacts the computational load of the rest of the analysis. Quantitation is then based on integration of the defined features. This step is prone to errors because of the complexity of spectra from biological sources and unresolved features along any dimension of analysis. The pattern recognition step of metabolomics continues to evolve as big data projects become more commonplace. However, certain existing multivariate analyses are suited to metabolomics data. Principle component analysis (PCA) and partial least-squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) are both widely used [9]. The benefit of both of these methods is that they distinguish groups based on specific variables by reducing an otherwise impractical number (thousands) of variables to a manageable number (often around 10). The loading plots of PCA and PLS-DA then describe the contribution of specific features to the differences between the groups, greatly facilitating identification and downstream validation of targets. An illustration of the PLS-DA driven workflow can be seen in Figure 4. Biologically informed interpretation such as pathway grouping can be performed before or after multivariate analysis [9].

Figure 3. Representative 600 MHz 1H NMR spectra showing the methyl resonances of 20 mM valine and 5 mM isoleucine (A) with manual integration of defined regions, (B) after deconvolution with peak fitting and (C) using binned integral regions.

Fitted data in (B) are shown in blue and green for valine and isoleucine, respectively, with the residual discrepancy between calculated and actual spectrums shown as a dashed red line. Peak fitting was performed by ACDlabs Spectrum Processor.

Reproduced with permission from [8].

Figure 4. Partial least-squares-discriminant analysis and biomarker validation to distinguish metabolic signatures of responsiveness and resistance to imatinib in human Bcr-Abl positive cells from CML patients.

The leukemic cell lines K562 and LAMA84 were treated with imatinib (1µM) for 24 h. Statistical PLS-DA on high-resolution 1H NMR spectra (both extras and medium spectra sets were used) allows for group clustering sensitive untreated cells (gray squares) versus sensitive cells treated with imatinib (black circles) versus resistant cells treated with imatinib (open triangles). The group clustering was based on changes in glucose, lactate, choline intermediates and glutamine, with a minor contribution from creatinine and alanine.*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Cho: Choline; CML: Chronic myeloid leukemia; GPC: Glycerophosphocholine; PC: Phosphocholine; tCr: Total creatine (includes creatine and phosphocreatine).

Reproduced with permission from [16].

Even with good pattern finding approaches visualization of complex data remains a difficult issue. The problem of reducing dimensionality of data while retaining the utility of the visualization to convey a finding is nontrivial. Adopting techniques from other–omics methods may be useful. Relative changes can be shown through a heatmap projection, and diagnostic ability of a model is visualized well through receiver operating characteristic curves. As a rule of thumb, in targeted approaches, metabolite identification is often based on the specificity of the analysis. In untargeted approaches, metabolite identification is often the last step in analysis because it can be the most time, resource and effort intensive. Expanding databases of chemical information may reduce this significant barrier.

Validation in metabolomics is one of the most critical steps in the process from metabolomics discovery to translation and clinically relevant findings. Aspects of validation include complete structural determination and moving from discovery-based metabolomics to hypothesis-testing gold-standard analytical methods. Validation should also include repeating the same findings in at least one independent cohort of samples. Despite the emergence of metabolomics from a scientific lineage of rigorous gold-standard analytical methods based on MS and NMR platforms, many metabolomics studies do not adequately validate their findings. This is unfortunate because the full potential of metabolomics should translate to incredible benefit to patients, clinicians and scientists.

NMR-based methodology

Despite the limitation of analysis in the mid-µM range for metabolite concentration, NMR is a widely used tool for metabolomics. NMR is considered the gold-standard method for analyte identification and gives a directly quantitative measurement relating amount of analyte to signal [8]. Absolute quantification is possible with a single internal standard, and some methods are proposing quantitation based off electronic output alone. 1H NMR has found the most use in metabolomics, due to speed of spectral acquisition and signal resulting from a relatively higher number of atoms participating in the resonance versus other atoms [16]. Other studies have used 13C or 31P nuclei in NMR as well as employing magnetic resonance to image metabolism in vivo.

Practical considerations in NMR include the field strength of the NMR spectrometer, the number of atoms contributing to the resonance and the region where the resonances are detected. Advances in NMR have included: stronger magnets resulting in increased field strength (from routine 500 to high-end 900 MHz), hyperpolarization techniques leading to increased signal to noise and advanced pulse techniques resulting in narrower resonances [9]. With the use of ultrashielded magnets, it is now possible to combine flow-injection NMR and mass spectroscopy to a total analysis system with minimized space requirements and controlled by single software. Such a system can also be used for sample preparation in an integrated manner.

High-resolution 1H NMR is extremely useful for biomarker studies in biofluids such as urine with high concentrations of endogenous metabolites because the intensity of the signal will not vary due to matrix effects. 1H NMR spectra of different sets of urine samples show high similarity. The range from 0.5 to 4.5 ppm provides a wealth of information in the NMR spectrum of urine. All the aliphatic protons from high abundance metabolites such as creatinine, creatine, urea, pyruvate and citrate will give intense peaks in the NMR spectra. It is worth mentioning that alanine which is found in relatively low levels in urine (<1 mM) can be readily identified by a doublet at 1.48 ppm that has a constant spin–spin interaction of 7.22 Hz. This is because there are only a few other resonating protons around that frequency. At 2.34 ppm is a singlet corresponding to pyruvate that is formed during lactam oxidation. Citrate is also present in all of the urine spectra and is visible as two doublets at 2.55 and 2.70 ppm with a large coupling constant of 16 Hz. Dimethylamine shows a singlet that can sometimes overlapped with the citrate doublet at 2.73 ppm, depending on the pH of the sample. Creatinine is one of the major metabolites in urine, and on its accurate measurement depend the values of different other metabolites reported in urine, so it is particularly necessary be able to correctly quantify it.

The NMR spectral results generated in a metabolomic study yield a unique metabolic fingerprint for each biological fluids sample consisting of thousands of overlapping resonances, and measurement of a small set of signals will not reflect the full potential of the spectral profile [17]. If the status of a given organism changes, such as in a diseased state or following, smoking or after exposure to a drug, a unique metabolic fingerprint or signature could potentially reflect this change. Multivariate statistical methods provide an expert means of analyzing and maximizing information recovery from complex NMR spectral data sets [18]. Detailed inspection of NMR spectra and integration of individual peaks can give valuable information on dominant biochemical changes; however, small variations in spectral information can easily be overlooked. Therefore, pattern recognition methods have been employed to map the NMR spectra into a representative low dimensional space such that any clustering of the samples based on similarities of biochemical profiles can be determined and the biochemical basis of the pattern interrogated [19]. Early pattern recognition studies on NMR data employed a reductionist approach of preselecting metabolite signals of interest [20].

NMR instruments coupled with LC-MS provide the ultimate metabolomics tool by providing overlapping and nonoverlapping information. NMR remains dominant in the quantitative analysis of highly abundant small molecules and can give an overview of changes in a biological sample without prior knowledge. MS is currently better suited for the analysis of compounds at low abundance, although it can of course also be used for analyzing high abundance metabolites as well. Dealing with the wide variation in concentration of human metabolites of ~10 orders of magnitude, multiple approaches are required.

Mass-spectrometry-based methodology

MS-based metabolomics is chosen by researchers because of robustness, sensitivity and ability to measure diverse metabolites. Improvements in instrumentation have led to gains in sensitivity, so reporting of picomole to femtomole levels are common in MS analysis. Although MS is a destructive technique, because of sensitivity only small amounts of sample are used for analysis whereby additional modes of MS analysis can be used to reinterrogate the same samples [4].

MS platforms for metabolomics differ by ionization technique and the mass analyzer. Resolving power, scan speed and mass accuracy are important attributes of an MS platform and polarity of analysis also influences the results. MS can be coupled to orthogonal modes of separation in-line such as GC-MS, capillary electrophoresis-MS and LC-MS. A summary of ionization techniques and separation modes are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Diagram showing the general mass range and polarity ranges covered by different MS ionization and chromatography techniques.

Reproduced with permission from [5].

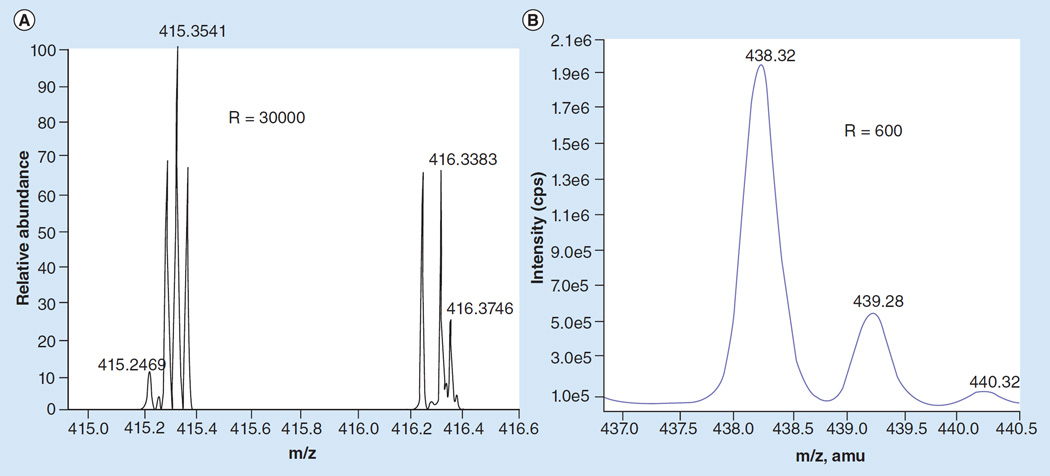

In reported metabolomics experiments the most common ionization technique for biomolecules was ESI followed by APCI [4]. Other ionization techniques such as MALDI and desorption ESI can be used to provide a spatial dimension to metabolomics data or analyze an intact biological sample. Mass analyzers in the order of increasing resolution include: quadrupole, linear ion trap, multiple designs of TOF, Orbitrap and Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR). Increasing resolution massively increases the specificity and informational content of spectra as is clearly demonstrated in Figure 6. Mass accuracy of Orbitrap analyzers can be better than 1–3 part per million, and FT-ICR have reported accuracy into subpart per million in the small molecule m/z range. Higher order MS (e.g., MS/MS or MSn) acquired in a data dependent or independent mode can give structural information on an analyte, useful for molecular identification. Hybrid instruments combining different mass analyzers in sequence or parallel along the ion path are particularly useful for MSn.

Figure 6. Comparison of spectra between high- and low-resolution mass spectrometers.

(A) High-resolution lysolipid spectra obtained on a Thermo Fisher Orbitrap with a resolution of 30,000. (B) Low-resolution lysolipid spectra obtained on an AB Sciex 4000 QTrap with a resolution of 600.

Reproduced with permission from [6]. © American Chemical Society (2013).

Direct MS analysis refers to the infusion of the sample without chromatographic separation into the MS, allowing high throughput and long spectral acquisition times for high- and ultrahigh-resolution mass analyzers such as Orbitraps and FT-ICR. However, it reduces specificity and sensitivity significantly. Emerging techniques such as ion mobility or innovative ionization techniques may make this technique more useful. GC-MS is a popular technique for analysis of volatile compounds and derivatized nonvolatile compounds. However, because many biomolecules are neither thermally nor chemically stable under analysis conditions, GC-MS is transitioning to use as a complimentary technique in metabolomics. LC-MS is increasingly the mainstay of MS-based metabolomics. LC using normal-phase and reversed-phase chemistries are widely used. C18 reversed phase is the most utilized, due to robustness and selectivity but polar molecule analysis by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography is also growing in popularity. Reducing the particle size of LC packing material to sub-2 µm has created the technique of ultrapressure liquid chromatography (UPLC), increasing chromatographic resolution and peak capacity. Although UPLC can reduce peak width to timescales incompatible with high-resolution mass analyzers, adapting nanoflow-UPLC methods to metabolomics can circumvent this problem [21].

In MS analysis, molecules are ionized and introduced into mass spectrometer, then separated and analyzed resulting in the determination of the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). A single analyte may give rise to multiple m/z values due to multiple charge states and adduct formation resulting in collinear values. It is also important to understand that MS is not inherently a quantitative tool. The amount of analyte in sample is not always proportionate to the amount of signal read by the detector due to the large number of possible confounders in analysis. Ion suppression, losses during analysis, adduct formation, dynamic range of instrumentation and many other factors can systematically bias an improperly controlled metabolomics experiment. Even rigorous quality control of an analysis or proper randomization of sample analysis may reduce other sources of bias but does not overcome the inherent limits of MS as a quantitative tool. Gold-standard stable isotope dilution methods remain the truly rigorous test of metabolite abundance in MS analysis. Metabolite identification has been significantly improved with accurate mass databases and tandem MS fragmentation information. However, this still remains a very labor-intensive endeavor, particularly for lipid-derived metabolites.

Clinical issues for metabolomics in cancer research

The importance of well-characterized, carefully collected clinical samples cannot be overstated. It is important that the biobanked samples used for metabolomics studies should reflect the biological variability of the targeted population [14]. There are some serious issues that relate to the ‘right to privacy’ of biobanked samples that must be dealt with at the time of sample acquisition. There is a need for specimens to be anonymous or deidentified from sensitive clinical information. However, this has to be balanced by the need of researchers to access information about a particular sample without knowing the identity of the donor. This requires a sophisticated system in which information that could identify the donor is coded, and then key which could decipher the identity of the donors is stored in a separate location. This serves to protect the donor but allows contact to be made if this is absolutely necessary.

The biobanked samples must be well annotated with standard operating procedures in place to limit preanalytical problems that could arise for handling of biospecimens. One of the major problems that can arise is differences in the time between tissue or biofluid harvesting and stabilization, either by rapid cooling or with chemical additives. It is critical to reduce to a minimum the amount of time that harvested tissues spend under ischemic conditions before stabilization. Similarly, biofluids should be frozen at −80°C as rapidly as possible to prevent degradation of potential biomarkers. Failure to address these concerns will result in expensive metabolomic studies that generate data, which cannot be interpreted or reproduced.

Metabolomics studies in lung cancer

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide and so numerous studies have examined gene/protein expression profiles in order to provide useful information on the metabolic dysfunctions that occur in lung cancer. It was reasoned that this might provide insight into potential therapeutic interventions. However, gene/protein expression profiles do not give a complete picture of metabolic changes that result in the malignant phenotype. This is because (as noted by Fan et al.) post-translational modifications, protein inhibitors, allosteric regulation by effector metabolites, alternative gene functions and compartmentalization can induce also significant metabolic changes [11]. Therefore, stable isotope-resolved metabolomics (SIRM) using [U-13C6]-glucose has been employed in combination with NMR- and MS-based methodology in order to search for key metabolic transformation processes that occur in tumors [12]. The SIRM methodology made it possible to conduct a systematic determination of human tumor-specific metabolic alterations by conducting metabolic profiling investigations as a complement to transcriptomic and proteomic studies [11]. A combination of NMR and MS were used to analysis of labeling patterns of individual atoms (isotopomers) in a wide range of metabolites when conducting stable isotopic tracer studies. Thus, 2D 1H total correlation spectroscopy and 1H-13C heteronuclear single quantum coherence experiments were able to profile [13C]-enrichment at specific atomic positions ([13C]-positional isotopomers) while MS analyses enabled quantification of [13C]-mass isotopomers, regardless of the labeled position. Such [13C]-labeling profiles were crucial to simultaneously tracing the multiple biochemical pathways shown in Figure 1.

Metabolic changes in lung tissues were monitored after infusing [U-13C6]-glucose into human lung cancer patients. The infusion was followed by resection and processing of paired noncancerous lung and non-small-cell carcinoma tissues. NMR and GC-MS were then used for [13C]-isotopomer-based metabolomic analysis of the extracts of tissues and blood plasma. Many primary metabolites were consistently found at higher levels in lung cancer tissues than their surrounding noncancerous tissues. [13C]-enrichment in lactate, alanine, succinate, glutamate, aspartate and citrate was also higher in the tumors, in keeping with more active glycolysis and Krebs cycle in the tumor tissues. Particularly noteworthy were the enhanced production of the aspartate isotopomer with three [13C]-labeled carbons and the buildup of 2,3-[13C2]-glutamate isotopomer in lung tumor tissues. This was consistent with the transformations of glucose into aspartate or glutamate from glycolysis, anaplerotic pyruvate carboxylation and the Krebs cycle (Figure 1). Pyruvate carboxylate activation in tumor tissues was also shown by an increased level of pyruvate carboxylase mRNA and protein.

Metabolomics studies in prostate cancer

Serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) remains the major biomarker employed for monitoring prostate cancer treatment and for surveillance. Unfortunately, the low specificity and sensitivity means that it has little utility in prostate cancer screening although specificity is increased when used in combination with a rectal examination. For men diagnosed with prostate cancer, prognostic algorithms or nomograms utilizing primarily tumor pathology and PSA are available. Although these tools generally work well, significant variability in prediction exists for men at both the low- and high-end of the risk spectrum. Metabolomic profiling in prostate cancer has attracted increased interest, particularly since a provocative study suggested that the amino acid sarcosine (N-methylglycine) is a potential cancer biomarker [22].

Significant progress has been made in the application of NMR spectroscopy and magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) for the detection, diagnosis and characterization of dysregulated metabolism in human prostate cancer [23]. A number of metabolic changes have been detected in prostate cancer cells when compared with normal cells, reflecting metabolic reprogramming across multiple pathways, suggesting that metabolomics approaches could be useful in guiding diagnosis and therapy. For example, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging combined with 3D-MRSI images was used to guide sampling of postsurgical prostatectomy specimens to areas of healthy tissue (high citrate and polyamines coupled with low choline) or cancer (low citrate coupled with high choline), which were then evaluated by high-resolution magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy [22]. Prostate cancer specimens had lower concentrations of citrate and polyamines when compared with healthy matched epithelial tissue. However, the concentrations of citrate and polyamines were similar to those found in healthy stroma. A subsequent study found higher choline and phosphatidylethanolamines concentrations together with decreased ethanolamine concentrations in prostate cancer tissue samples when compared with benign matched epithelial tissues; stromal tissues also exhibited lower levels of choline-containing metabolites [22]. These changes suggested there was enhanced synthesis and degradation of phospholipid membranes coupled with increased cellular proliferation. This was confirmed by comparison of biopsy tissues from men with and without prostate cancer, which revealed increased ratios of total choline to citrate ratios and glycerophosphocholine + phosphocholine to creatine together with a decreased ratio of citrate to creatine.

Unbiased metabolomic profiling using LC/GC-MS identified six metabolites (sarcosine, uracil, kynurenine, glycerol-3-phosphate, leucine and proline), which increased in tumor samples during progression when compared with benign prostate tissue adjacent to the tumor. Among these metabolites, sarcosine was the most significantly different. A similar result was found in an independent set of tissue samples in which sarcosine was analyzed by stable isotope dilution GC-MS. In contrast to the results of metabolomic profiling of prostate tissue, an unbiased analyses of matched plasma and postdigital rectal exam urine sample was unable to discriminate between positive biopsies of prostate cancer and negative biopsies. However, sarcosine concentrations (when normalized to alanine) were significantly increased in both urine sediment and urine supernatant from biopsy-positive men. Similar results were observed when sarcosine was normalized to creatinine concentrations. In samples from men within the PSA values of 2–10 ng/ml, urinary sarcosine concentrations more reliably discriminated between biopsy-positive and biopsynegative men than PSA, the widely used biomarker of prostate cancer [22]. Unfortunately, the utility of sarcosine concentrations as a biomarker for prostate cancer still remains controversial in spite of two recent large studies. The association between serum sarcosine levels and risk of prostate cancer in 1122 cases (813 nonaggressive and 309 aggressive) and 1112 controls was studied using LC-MS-based methodology [24]. A significantly increased risk of prostate cancer was observed with increased levels of serum sarcosine [24]. In contrast, a larger nested case–control study of 3000 prostate cancer cases and 3000 controls showed that high serum sarcosine and glycine concentrations (determined by GC-MS) were associated with a reduced prostate cancer risk of borderline significance [25].

Metabolomics studies in breast cancer

1H-NMR metabolomics has been used to examine the effects of hypoxia in the MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cell line, both in vitro and in vivo [26]. MDA-MB-231 cell in culture were compared with respect to their metabolic responses during growth under either hypoxic (1% O2) or normoxic conditions. Orthogonal PLS-DA was used to identify a set of metabolites that were responsive to hypoxia. Intracardiac administration of MDA-MB-231 cells was also used to generate widespread metastatic disease in immunocompromised mice. Serum metabolite analysis was conducted to compare animals with and without a large tumor burden. A subset of metabolites including amino acids and those derived from energy metabolites indicative alterations in energy metabolism, and possibly protein synthesis or catabolism. These results suggested that metabolite patterns identified might prove useful as a marker for intratumoral hypoxia in breast cancer.

Estrogen receptor positive (ER+) breast cancer tissue was compared with estrogen receptor negative (ER−) using GC-MS-based metabolomics [27]. Increased concentrations of β-alanine, 2-hydroyglutarate, glutamate, xanthine and decreased concentrations in glutamine were found in the ER-subtype. β-Alanine demonstrated the strongest (2.4-fold) change between ER− and ER+ breast cancer. In a correlation analysis with genome-wide expression data in a subcohort of 154 tumors, a strong negative correlation between β-alanine and 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase (ABAT) was observed. Immunohistological analysis confirmed downregulation of the ABAT protein in ER− breast cancer. It was concluded that increased glutamate and decreased glutamine concentrations in ER− breast cancer compared with ER+ breast cancer and compared with normal breast tissues were indicative of a potential role for glutaminase therapy ER− breast cancer. A separate study conducted a serum metabolic study in breast cancer using a combination of NMR spectroscopy and LC-MS [28]. The study identified glutamine (together with threonine, isoleucine and linolenic acid) as being significantly dysregulated in chemotherapy-resistant breast cancer. These results suggested that more personalized neoadjuvant treatment protocols could be devised for breast cancer patients using metabolomics methodology.

Several recent studies have developed multiplexed methods of analysis in order to expand the utility of metabolomics profiling capabilities to breast cancer biomarker discovery. Unfortunately, most of the reported studies did not examine whether the biomarkers were present in other cancers or other disease states and so the sensitivity and specificity of the resulting biomarkers has not been completely established. For example, five potential urinary biomarkers for breast cancer were identified using GC-MS by simply comparing breast cancer patients with normal controls and none of them was characterized [29]. Gene expression profiles and urinary metabolomics methodology was employed to select candidate biomarkers identified by GC-MS from 50 breast cancer patients and 50 normal subjects. Among the altered metabolic pathways, four metabolic biomarkers such as homovanillate, 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, 5-hydroxyindoleacetate and urea, were identified [29]. In a more extensive metabolomics study, a comprehensive metabolic map of breast cancer was constructed by GC-MS analysis [29]. A total of 368 metabolites were significantly dysregulated in cancer tissue compared with normal tissues. The cytidine-5-monophosphate/pentadecanoic acid ratio was the most significant discriminator and allowed detection with a sensitivity of 94.8 and a specificity of 93.9%. Metabolic phenotypes of breast cancers in urine have also investigated. Intermediates of the Krebs cycle and metabolites relating to energy metabolism, amino acids and gut microbial metabolism were perturbed and illustrated that urinary metabolomics may be useful for detecting early-stage breast cancer [29]. Finally, high sensitivity methodology was developed recently for the analysis of the serum estrogen metabolome in breast cancer [30]. Using this assay, obesity was found to associated with increased extraglandular estrogen production and metabolism before the onset of puberty in girls [31]. Therefore, further estrogen biomarker studies will be required in order determine whether there is any increase in breast cancer risk in obese prepubertal girls.

Metabolomics studies in colorectal cancer

There is a need for biomarkers to complement strategies based on colonoscopy in order to improve the detection of colorectal cancer. Patients with early stage colorectal have a significant higher five-year survival rates compared with patients diagnosed at late stage. In spite of substantial efforts, there are no useful biomarkers for the early detection of colorectal cancer. The most widely used biomarker (serum carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA]) is also elevated in breast and pancreatic cancer. This means that serum CEA is used mainly for surveillance following resection and for monitoring recurrence in advanced disease. Therefore, metabolomics-based strategies can potentially lead to the discovery and validation of new biomarkers for the early detection of colorectal cancer [32].

Ritchie et al. used direct infusion high-resolution MS/MS coupled with LC-MS to evaluate the utility of selected serum biomarkers for discriminating between colorectal cancer and healthy subjects [33]. This led to the identification of previously unknown hydroxylated polyunsaturated ultralong chain fatty acid metabolites with 28 and 36 carbons that were downregulated in the serum of colorectal cancer patients. These metabolites can be readily quantified in serum and a decrease in their concentration appears to be highly sensitive and specific for the presence of colorectal cancer. In a more recent study, metabolomics analysis was conducted using GC-MS in which serum from colorectal cancer patients was compared with sex-matched healthy volunteers [34]. Significant differences in serum 2-hydroxybutyrate, aspartic acid, kynurenine and cystamine concentrations were observed between cancer patients and controls with sensitivity and specificity of 85.0 and 85.0%, respectively. In contrast, the sensitivity and specificity accuracy of CEA were 35.0, 96.7%, respectively, and cancer antigen (CA19–9) were 16.7 and 100%, respectively. The prediction model established with the GC-MS-based serum metabolomic analysis might be useful for the early detection of colorectal cancer, although the sensitivity and specificity suggests there will likely be a substantial false positive and false negative rate, which will limit its utility.

Metabolomics studies in pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer is perhaps the most compelling cancer for biomarkers of early detection. As noted above, the disease takes 15 years to develop and therapeutic options in late-stage disease are very limited. The most useful biomarker (serum CA19–5) is elevated in colon cancer and is also elevated in nonmalignant jaundice, liver cirrhosis. This contributes to its poor specificity and sensitivity. Specificity of CA19–5 as a pancreatic cancer biomarker is improved when combined with radiological imaging but its use is restricted to distinguishing between resectable and unresectable disease and for monitoring the effect of treatment. Metabolomic analyses could therefore potentially be useful for the development of new early detection biomarkers and for monitoring treatment with different chemotherapeutic drugs.

1H-NMR-based metabolomics methodology was employed to quantify 58 unique metabolites in serum samples from patients with benign hepatobiliary disease and from patients with pancreatic cancer [35]. Data were analyzed by ‘targeted profiling’ followed by supervised pattern recognition and orthogonal partial least-squares discriminant analysis of the most significant metabolites. The metabolomic profiles of serum from patients with pancreatic cancer were significantly different from that of patients with benign pancreatic disease. However, diabetes mellitus was identified as a possible confounding factor in the pancreatic cancer group and so diabetics were then excluded from the analysis. A multivariate analysis revealed that serum concentrations of glutamate and glucose were the most elevated metabolites in this more homogeneous pancreatic cancer group. In contrast creatine and glutamine were the most abundant metabolites found in serum samples from benign hepatobiliary disease patients. To examine the usefulness of these metabolites as potential biomarkers, a comparison was made to age- and gender-matched controls with benign pancreatic lesions that mimic cancer (n = 14 per group). The metabolic profile in serum from patients with pancreatic cancer remained distinguishable; however, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was only 0.83.

In a subsequent GC-MS metabolomics study, sera from patients with pancreatic cancer, healthy volunteers and chronic pancreatitis were compared [36]. The pancreatic cancer and healthy volunteers were randomly allocated to the training or the validation set. A diagnostic model was constructed using multiple logistic regression analysis in a training set study the results were confirmed by a subsequent validation set study. The model possessed sensitivity of 86.0 and specificity of 88.1% for pancreatic cancer. However, validation revealed a sensitivity of only 71.4 and a specificity of only 78.1% so the model has little utility for pancreatic cancer screening. More comprehensive LC-MS metabolomics studies could potentially yield a panel of biomarkers with higher sensitivity and sensitivity.

Metabolomics studies in leukemia

The recent discovery that leukemia is often associated with mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) has stimulated metabolic approaches to leukemia biomarkers [37]. Mutated IDH1 (cytosolic) and IDH2 (mitochondrial) function as reductases of α-ketoglutarate rather than converting isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate through oxidative decarboxylation. The reduction of α-ketoglutarate results in the specific formation of 2(R)-hydroxyglutarate suggesting that analysis of this metabolite in serum might serve as an early detection of leukemia and other disease such a glioblastoma multiforme where IDHs are mutated. In fact a significant correlation has been established between IDH mutations and serum 2-hydroxyglutarate [37]. However, the analyses did not examine the chirality of the 2-hydroxyglutarate. This suggests that improved specificity and sensitivity could be obtained by a more rigorous chiral analysis. Furthermore, the success of this metabolite as a leukemia biomarker provides encouragement for the detection of leukemia biomarkers when IDHs are not mutated.

Conclusion & future perspective

Metabolomics studies in cancer have been quite successful in helping to address mechanistic issues in cancer [1]. However, little progress has been made in improving upon the current biomarkers for the early detection of specific cancers or as an alternative for monitoring the effects of therapy or detection progression during therapy. NMR methodology lacks the sensitivity for early biomarker detection and GC-MS is restricted to low molecular weight metabolites that survive high temperature in the injection port of the instrument. The increase use of high-resolution LC-MS-based methodology offers to extend the range of metabolites to thermally labile higher molecular weight metabolites [38]. This is particularly relevant to the potential utility of the diverse esterified lipids, which constitute a diverse structurally complex set of >37,000 identified metabolites [39]. Examination of structures of lipids suggests that are potentially >100,000 different family members that have yet to be identified. Therefore, this could be a rich source of metabolomic biomarkers that will also provide novel pathways that can potentially be targeted for new cancer therapies [40,41]. It is noteworthy that that 2(R)-hydroxyglutarate is a specific metabolite of mutated IDHs in leukemia and glioblastoma multiform. The finding that serum 2-hydroxyglutarate quantified using an achiral LC-MS method correlate well with mutation of IDH in corresponding tumor samples [37] provides encouragement that metabolomics studies will eventually provide clinically useful assays that can be used to guide treatment. Hopefully, metabolomics-based methodology will also prove useful for the early detection of specific cancers.

Executive summary.

Currently available diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of cancer are inadequate, especially for pancreatic, ovarian and colorectal cancer.

Earlier diagnosis and intervention as well as biomarkers responsive to treatment can improve survival.

Translation of biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and therapy has been slower than the pace of discovery.

Untargeted and targeted metabolomics for discovery and validation of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers has shown promise but remains an evolving field.

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and liquid chromatography or gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry are the primary technologies in metabolic biomarker discovery and validation.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of NIH grants R01CA158328, P30ES023720, P30ES013508 and P30CA016520.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.O’Connell TM. Recent advances in metabolomics in oncology. Bioanalysis. 2012;4(4):431–451. doi: 10.4155/bio.11.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blair IA. Eliminating Bottlenecks for Efficient Bioanalysis: Practices and Applications in Drug Discovery and Development. London, UK: Future Science Group; 2015. Bioanalysis supporting disease biomarker discovery and validation; pp. 162–181. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blair IA. Analysis of estrogens in serum and plasma from postmenopausal women: past present, and future. Steroids. 2010;75(4–5):297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lei Z, Huhman DV, Sumner LW. Mass spectrometry strategies in metabolomics. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(29):25435–25442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.238691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forcisi S, Moritz F, Kanawati B, Tziotis D, Lehmann R, Schmitt-Kopplin P. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry in metabolomics research: mass analyzers in ultra high pressure liquid chromatography coupling. J. Chromatogr. A. 2013;1292:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milne SB, Mathews TP, Myers DS, Ivanova PT, Brown HA. Sum of the parts: mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Biochemistry. 2013;52(22):3829–3840. doi: 10.1021/bi400060e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang T, Watson DG, Wang L, et al. Application of holistic liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry based urinary metabolomics for prostate cancer detection and biomarker discovery. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barding GA, Jr, Salditos R, Larive CK. Quantitative NMR for bioanalysis and metabolomics. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012;404(4):1165–1179. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6188-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smolinska A, Blanchet L, Buydens LM, Wijmenga SS. NMR and pattern recognition methods in metabolomics: from data acquisition to biomarker discovery: a review. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2012;750:82–97. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciccimaro E, Blair IA. Stable-isotope dilution LC-MS for quantitative biomarker analysis. Bioanalysis. 2010;2(2):311–341. doi: 10.4155/bio.09.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan TW, Lane AN, Higashi RM, et al. Altered regulation of metabolic pathways in human lung cancer discerned by (13)C stable isotope-resolved metabolomics (SIRM) Mol. Cancer. 2009;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane AN, Fan TW, Bousamra M, Higashi RM, Yan J, Miller DM. Stable isotope-resolved metabolomics (SIRM) in cancer research with clinical application to nonsmall cell lung cancer. OMICS. 2011;15(3):173–182. doi: 10.1089/omi.2010.0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basu SS, Deutsch EC, Schmaier AA, Lynch DR, Blair IA. Human platelets as a platform to monitor metabolic biomarkers using stable isotopes and LC-MS. Bioanalysis. 2013;5(24):3009–3021. doi: 10.4155/bio.13.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore HM, Compton CC, Lim MD, Vaught J, Christiansen KN, Alper J. 2009 Biospecimen research network symposium: advancing cancer research through biospecimen science. Cancer Res. 2009;69(17):6770–6772. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S, Huang J, Abbassi-Ghadi N, Spanel P, Smith D, Hanna GB. Selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry analysis of exhaled breath for volatile organic compound profiling of esophago-gastric cancer. Anal. Chem. 2013;85(12):6121–6128. doi: 10.1021/ac4010309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serkova NJ, Spratlin JL, Eckhardt SG. NMR-based metabolomics: translational application and treatment of cancer. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2007;9(6):572–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gulston MK, Rubtsov DV, Atherton HJ, et al. A combined metabolomic and proteomic investigation of the effects of a failure to express dystrophin in the mouse heart. J. Proteome. Res. 2008;7(5):2069–2077. doi: 10.1021/pr800070p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karakach TK, Wentzell PD, Walter JA. Characterization of the measurement error structure in 1D 1H NMR data for metabolomics studies. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2009;636(2):163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou J, Xu B, Huang J, et al. 1H NMR-based metabonomic and pattern recognition analysis for detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2009;401(1–2):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coen M, Holmes E, Lindon JC, Nicholson JK. NMR-based metabolic profiling and metabonomic approaches to problems in molecular toxicology. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008;21(1):9–27. doi: 10.1021/tx700335d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snyder NW, Khezam M, Mesaros CA, Worth A, Blair IA. Untargeted metabolomics from biological sources using ultraperformance liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC-HRMS) J. Vis. Exp. 2013;75:e50433. doi: 10.3791/50433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trock BJ. Application of metabolomics to prostate cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2011;29(5):572–581. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeFeo EM, Wu CL, McDougal WS, Cheng LL. A decade in prostate cancer: from NMR to metabolomics. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2011;8(6):301–311. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koutros S, Meyer TE, Fox SD, et al. Prospective evaluation of serum sarcosine and risk of prostate cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian cancer screening trial. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(10):2281–2285. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Vogel S, Ulvik A, Meyer K, et al. Sarcosine and other metabolites along the choline oxidation pathway in relation to prostate cancer – a large nested case–control study within the JANUS cohort in Norway. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;134(1):197–206. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weljie AM, Bondareva A, Zang P, Jirik FR. (1)H NMR metabolomics identification of markers of hypoxia-induced metabolic shifts in a breast cancer model system. J. Biomol. NMR. 2011;49(3–4):185–193. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budczies J, Brockmoller SF, Muller BM, et al. Comparative metabolomics of estrogen receptor positive and estrogen receptor negative breast cancer: alterations in glutamine and beta-alanine metabolism. J. Proteomics. 2013;94:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei S, Liu L, Zhang J, Bowers J, et al. Metabolomics approach for predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2013;7(3):297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang AH, Sun H, Qiu S, Wang XJ. Metabolomics in noninvasive breast cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2013;424:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Q, Rangiah K, Mesaros C, et al. Ultrasensitive quantification of serum estrogens in postmenopausal women and older men by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Steroids. 2015;96:140–152. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mauras N, Santen RJ, Colon-Otero G, et al. Estrogens and their genotoxic metabolites are increased in obese prepubertal girls. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;100(6):2322–2228. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang A, Sun H, Yan G, Wang P, Han Y, Wang X. Metabolomics in diagnosis and biomarker discovery of colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;345(1):17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritchie SA, Ahiahonu PW, Jayasinghe D, et al. Reduced levels of hydroxylated, polyunsaturated ultra long-chain fatty acids in the serum of colorectal cancer patients: implications for early screening and detection. BMC Med. 2010;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishiumi S, Kobayashi T, Ikeda A, et al. A novel serum metabolomics-based diagnostic approach for colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bathe OF, Shaykhutdinov R, Kopciuk K, et al. Feasibility of identifying pancreatic cancer based on serum metabolomics. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(1):140–147. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi T, Nishiumi S, Ikeda A, et al. A novel serum metabolomics-based diagnostic approach to pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(4):571–579. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DiNardo CD, Propert KJ, Loren AW, et al. Serum 2-hydroxyglutarate levels predict isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations and clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(24):4917–4924. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-493197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mesaros C, Worth A, Snyder NW, et al. Bioanalytical techniques for detecting biomarkers of response to human asbestos exposure. Bioanalysis. 2015;7(9):1157–1173. doi: 10.4155/bio.15.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fahy E, Subramaniam S, Murphy RC, et al. Update of the LIPID MAPS comprehensive classification system for lipids. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl.):S9–S14. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800095-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kroemer G, Pouyssegur J. Tumor cell metabolism: cancer’s Achilles’ heel. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(6):472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dang CV. Links between metabolism and cancer. Genes Dev. 2012;26(9):877–890. doi: 10.1101/gad.189365.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]