Abstract

Objective

Randomized comparisons of acceptance-based treatments with traditional cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety disorders are lacking. To address this research gap, we compared acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to CBT for heterogeneous anxiety disorders.

Method

One hundred twenty eight individuals (52% female, mean age = 38, 33% minority) with one or more DSM-IV anxiety disorders began treatment following randomization to 12 sessions of CBT or ACT; both treatments included behavioral exposure. Assessments at pre-treatment, post-treatment, 6-month, and 12-month follow-up measured anxiety specific (principal disorder Clinical Severity Ratings [CSR], Anxiety Sensitivity Index, Penn State Worry Questionnaire, Fear Questionnaire avoidance) and non-anxiety specific (Quality of Life Index [QOLI], Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-16 [AAQ]) outcomes. Treatment adherence and therapist competency ratings, treatment credibility, and co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders were investigated.

Results

CBT and ACT improved similarly across all outcomes from pre- to post-treatment. During follow-up, ACT showed steeper CSR improvements than CBT (p < .05, d = 1.33) and at 12-month follow-up, ACT showed lower CSRs than CBT among completers (p < .05, d = 1.05). At 12-month follow-up, ACT reported higher AAQ than CBT (p = .08, d = .42; Completers: p < .05, d = .59) whereas CBT reported higher QOLI than ACT (p < .05, d = .43). Attrition and comorbidity improvements were similar, although ACT utilized more non-study psychotherapy at 6-month follow-up. Therapist adherence and competency were good; treatment credibility was higher in CBT.

Conclusions

Overall improvement was similar between ACT and CBT, indicating that ACT is a highly viable treatment for anxiety disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Several decades ago, the development of behavioral and cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders (Barlow & Cerny, 1988; Beck, Emery, & Greenberg, 1985) introduced time-limited, relatively effective treatments. Numerous randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses (e.g. Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006; Hofmann & Smits, 2008; Norton & Price, 2007; Tolin, 2010) have demonstrated the effectiveness of CBT for anxiety disorders, including panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, specific phobia and posttraumatic stress disorder, relative to wait-list and/or psychological control conditions. As a result of clinical efficacy and ease of implementation, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has become the dominant empirically validated treatment for anxiety disorders. However, a significant percentage of individuals with anxiety disorders do not respond to CBT (e.g., Barlow, Gorman, Shear, & Woods, 2000), relapse following successful treatment (Brown & Barlow, 1995), seek additional treatment (Brown & Barlow, 1995), or remain vulnerable to developing anxiety and mood disorders throughout the lifespan (see Craske, 2003). Further, the cognitive model, which posits that anxiety disorders stem from faulty cognitions and are treated by modifying the content of these cognitions, has been challenged by insufficient supporting evidence (see Longmore & Worrell, 2007) and theoretical arguments (see Brewin, 1996)

In attempt to broaden, improve upon, and provide theoretically strong alternatives to traditional (cognitive model-based) CBT, clinical researchers have shown increasing interest in mindfulness and acceptance-based treatments for psychopathology. Multiple treatment approaches have developed out of this exploration, including Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999), a behavioral therapy that cultivates mindfulness, acceptance, cognitive defusion (flexible distancing from the literal meaning of cognitions), and other strategies to increase psychological flexibility and promote behavior change consistent with personal values. Within ACT, psychological flexibility is defined as enhancing the capacity to make contact with experience in the present moment, and based on what is possible in that moment, persisting in or changing behavior in the pursuit of goals and values (Hayes et al., 1999). Case studies, multiple-baseline treatment studies and a single randomized clinical trial provide nascent evidence that ACT is an effective treatment for anxiety disorders, including obsessive compulsive disorder (Twohig et al., 2010), social anxiety disorder (Dalrymple & Herbert, 2007), panic disorder (Eifert et al., 2009), generalized anxiety disorder (Wetherell et al., 2011), and posttraumatic stress disorder (Orsillo & Batten, 2005). However, no randomized clinical trials for anxiety disorders have yet compared ACT with the gold standard therapy for anxiety disorders, CBT.

Several studies have compared ACT and CBT within general clinic samples. One randomized effectiveness trial (n=101) in undiagnosed anxious and depressed patients (Forman, Herbert, Moitra, Yeomans, & Geller, 2007) compared ACT and CBT1, concluding that the two treatments were equally effective across symptom outcome measures, but operated via somewhat different mechanisms. A small (n=28) randomized treatment study comparing ACT and CBT for undiagnosed “general clinic patients” (Lappalainen et al., 2007) found that ACT reduced symptoms to a greater degree than CBT and effected treatment processes at a different rate. In neither study, however, were anxiety disorders formally diagnosed, significantly limiting the conclusions for the treatment of anxiety disorders. Roemer, Orsillo and colleagues (2008) developed an acceptance-based treatment for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) that integrated several ACT principles, and found it to be significantly superior to a waitlist control group for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. However, this promising treatment was developed for generalized anxiety disorder alone and it has not yet been compared to another active treatment.

In summary, important work has begun to investigate ACT for anxiety disorders but studies to date have not compared ACT to the most evidence-based psychotherapy for most anxiety disorders, CBT. Directly comparing traditional CBT and ACT for anxiety disorders within a randomized clinical trial bridges a vital gap in the empirical treatment literature, fulfilling the gold-standard method for investigating the relative efficacy of two treatments for anxiety disorders (Chambless & Hollon, 1998). Further, it provides an opportunity to compare the efficacy of treatment packages that contain distinct strategies for dealing with maladaptive cognitions (change the content of thoughts in CBT vs. change the context by challenging the need to respond rigidly and literally to cognitions in ACT) and uncomfortable internal experiences (to master and reduce anxiety in CBT vs. open towards and accept anxiety in ACT), and that promote different treatment goals (anxiety reduction in CBT vs. living a valued life in ACT).

The current study compares ACT and CBT in a mixed anxiety disorders sample for two reasons. First, ACT (Hayes et al., 1999) originally was developed for the treatment of psychopathology in general rather than a specific disorder in particular. The ACT protocol used in the current study (Eifert & Forsyth, 2005) was designed for application across all of the anxiety disorders, with the content of values-guided behavioral exercises tailored to specific anxiety disorders. Second, CBT shares common treatment elements across the anxiety disorders with variation in content specific to each disorder. We thus designed a CBT manual that addressed all anxiety disorders via branching mechanisms specific to each disorder. Our CBT protocol included the same basic treatment elements across all of the disorders (e.g., psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, exposure – see Methods) but tailored the content of these elements to each specific disorder, an approach we have successfully tested in previous studies (e.g., Craske et al., 2011).

We assessed patients at four longitudinal measurement points, including pre-treatment, post-treatment, 6-month follow up, and 12-month follow up, providing a thorough assessment of treatment-related change over time. Due to limited extant data, we did not make specific predictions regarding whether one treatment would lead to greater reductions in anxiety disorder-related symptoms than the other treatment. Rather, investigating this question represented a central study aim. However, given the emphasis in ACT on psychological flexibility and valued living, we hypothesized that these measures would improve to a greater degree following ACT than CBT.

METHODS

Participants

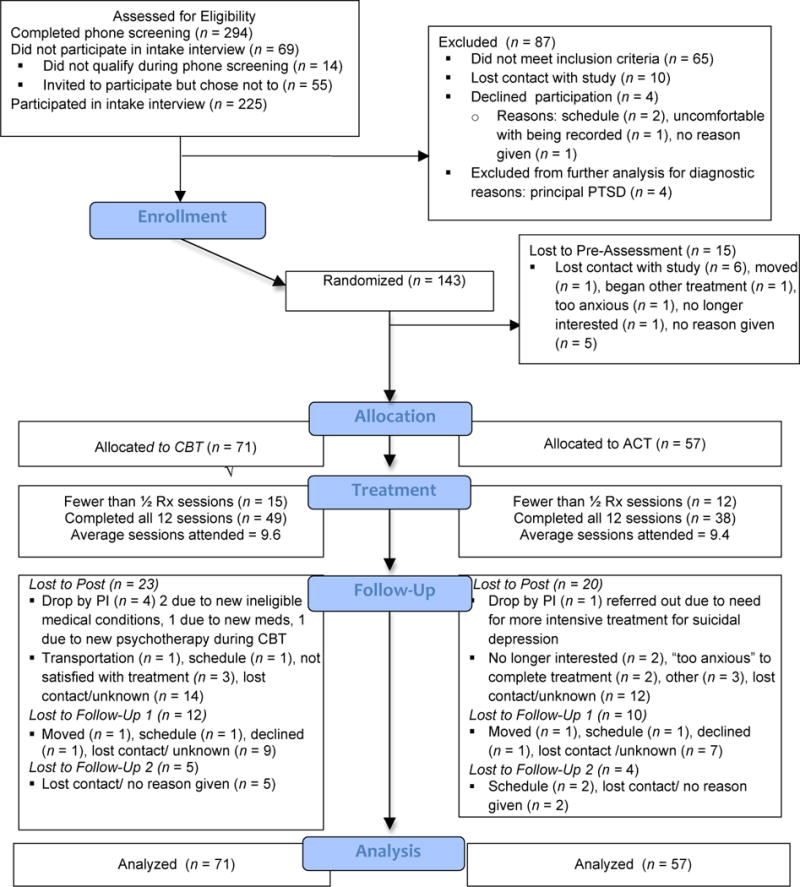

One hundred and forty-three participants (Ps) meeting DSM-IV criteria for a diagnosis of one or more anxiety disorders, including panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (PD/A), social anxiety disorder (SAD), specific phobia (SP), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)2, were randomized to ACT (n = 65) or CBT (n = 78). All Ps who began treatment (n = 128) were included in the intent-to-treat (ITT) sample (n=57 ACT, n=71 CBT). See Table 1 for ITT sample characteristics and Figure 1 for patient flow. Fifteen of the original 143 Ps, blinded to treatment randomization (unaware if they had been randomized to ACT or CBT), dropped prior to treatment initiation. Because pre-treatment attrition gave us no information about treatment preference or response, we did not analyze those Ps further. Ps who dropped prior to treatment did not differ significantly from Ps who began treatment on any sociodemographic variable from Table 1 (ps ≥ .20), nor did not differ by blind assignment to ACT vs. CBT (n = 8 each, p = .66). Ps who dropped treatment showed somewhat higher CSRs (M = 6.07, SD = .96) relative to Ps who began treatment (M = 5.63, SD = .92), but group differences were small and did not reach statistical significance p = .08. pη2 = 02. Eleven of the 15 Ps (73%) dropped prior to completing the pretreatment questionnaire assessment; therefore, we could not determine if they differed from Ps who initiated treatment on questionnaire measures.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Intent-To-Treat Sample

| Characteristic | TOTAL (n=128) |

ACT (n=57) |

CBT (n=71) |

t value or χ2 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 52.3% (67/128) |

50.0% (28/56) |

54.9% (39/71) |

.43 | .51 |

| Reported race/ethnicity | .82 | .36a | |||

| White | 67.2% (84/125) |

71.4% (40/56) |

63.8% (44/69) |

||

| Hispanic/Latino/a | 12.0% (15/125) |

10.7% (6/56) |

13.0% (9/69) |

||

| African-American/Black | 8.8% (11/125) |

7.1% (4/56) |

10.1% (7/69) |

||

| Asian-American/Pacific Islander | 8.0% (10/125) |

8.9% (5/56) |

7.2% (5/69) |

||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | .08% (1/125) |

1.8% (1/56) |

0.0% (0/69) |

||

| Age, in years | 37.93 (11.70) Range: 19–60 |

38.16 (12.41) |

37.75 (11.19) |

−.20 | .85 |

| Education, in years | 15.41 (2.07) Range: 9–21 |

15.59 (2.01) |

15.27 (2.12) |

−.86 | .39 |

| Marital Status | .19 | .91a | |||

| Married/Cohabiting | 32.3% (41/127)b |

32.1% (18/56) |

32.4% (23/71) |

||

| Single | 58.3% (74/127) |

57.1% (32/56) |

59.2% (42/71) |

||

| Other | 10.2% (13/127) |

10.7% (6/56) |

8.5% (6/71) |

||

| Children (1+) | 28.0% (35/125) |

30.4% (17/56) |

26.1% (18/69) |

.28 | .60 |

| Currently on psychotropic medication | 48.0% (61/127) |

44.6% (25/56) |

50.7% (36/71) |

.46 | .50 |

|

| |||||

| Primary diagnosis | 4.67 | .32 | |||

| Panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) | 41.7% (53/127) |

32.1% (18/56) |

49.3% (35/71) |

3.79 | .052 |

| Social anxiety disorder | 19.7% (25/127) |

23.2% (13/56) |

16.9% (12/71) |

.79 | .37 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 20.5% (26/127) |

25.0% (14/56) |

16.9% (12/71) |

1.26 | .26 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 13.4% (17/127) |

16.1% (9/56) |

11.3% (8/71) |

.62 | .43 |

| Specific Phobia | 4.7% (6/127) |

3.6% (2/56) |

5.6% (4/71) |

.69d | |

| Comorbid anxiety disorder (1+)c | 33.1% (42/127) |

39.3% (22/56) |

28.2% (20/71) |

1.75 | .19 |

| Comorbid depressive disorderc | 23.6% (30/127) |

23.2% (13/56) |

23.9% (17/71) |

.01 | .92 |

| Principal disorder clinical severity rating (mean) | 5.62 (.92) | 5.70 (.89) | 5.55 (.94) | .94 | .35 |

For race/ethnicity and marital status, analyses assessed group differences in minority versus white and married versus non-married status.

Demographic data was missing for 1 P.

Comorbidity was defined as a clinical severity rating of 4 or above on the ADIS

Fisher’s exact test p value was reported due to small n.

Figure 1.

Patient Flow

Ps were recruited from the Los Angeles area in response to local flyers, Craig’s List and local newspaper advertisements, and referrals. The study took place at the Anxiety Disorders Research Center at the University of California Los Angeles, Department of Psychology.

Ps were either medication-free or stabilized on psychotropic medications for a minimum standard length of time (1 month for benzodiazepines and beta blockers, 3 months for SSRIs/SNRIs and heterocyclics). Also, Ps were psychotherapy-free or stabilized on alternative psychotherapies other than cognitive or behavioral therapies, that were not focused on their anxiety disorder, for at least 6 months prior to study entry3. Ps were encouraged not to change their non-study medication or alternative psychotherapy during the course of the study. Exclusion criteria included active suicidal ideation, severe depression (CSR > 6 on ADIS-IV, see below), or a history of bipolar disorder, psychosis, mental retardation or organic brain damage. Ps with substance abuse or dependence within the last 6 months, or with respiratory, cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological, muscular-skeletal diseases or pregnancy were excluded.

Ps received 12 weeks of reduced-cost, sliding scale ($0–100/session) individual treatment, and received $15–$25 in cash or a gift certificate upon completion of the post-treatment and each followup assessment. Ps were reimbursed for UCLA parking fees for the assessments ($8–$10). The study was fully approved by the UCLA human subjects protection committee; full informed consent was obtained from all Ps, including for video- and audiorecordings.

Design

Ps were assessed at pre-treatment (Pre), post-treatment (Post), and at 6 months (6mFU) and 12 months (12mFU) after Pre. Assessments included a diagnostic interview, self-report questionnaires, and a 2 to 3 hour laboratory assessment (except at 6mFU) reported elsewhere. Assessors were blind to treatment condition. Randomization sequences were produced by www.randomizer.org CBT to ACT. Because fewer Ps were recruited in the fourth compared to the third quarter, the total number of Ps who began treatment in each condition was unequal (n = 57 to ACT; n = 71 to CBT). To maximize statistical power for the main group comparison hypotheses, we did not stratify patients on any variables.

Treatments

Following the Pre ADIS-IV and laboratory assessments, Ps were randomized to treatment condition. Ps received twelve weekly, 1-hour individual CBT or ACT therapy sessions based on detailed treatment manuals delivered by doctoral student therapists4. If clients presented with multiple anxiety disorders, treatment focused on the principal disorder. Following the 12 sessions, therapists conducted follow up phone calls once per month for 6 months, allowing 20–35 minutes per call to check in and troubleshoot in a manner consistent with the assigned therapy condition, to enhance long term outcomes (see Craske et al., 2006).

Therapists

Clinical psychology doctoral students at UCLA served as study therapists. The majority of therapists were relatively naïve to CBT and ACT and inexperienced more generally (i.e., in their first or second year of treating patients)5. Therapists were assigned to ACT, CBT, or both (i.e., treated in both CBT and ACT, though never at the same time), depending on the need for therapists in a particular condition and the availability of training in that condition (e.g., a multi-day training workshop with an ACT or CBT expert, see below). There were a total of 39 therapists; eighteen therapists worked exclusively in CBT, 9 worked exclusively in ACT, and 11 treated both ACT and CBT Ps (but never at the same time). Generally, therapists treated 1–2 patients at a time and 3–6 therapists worked within each treatment condition at a time. The mean number of patients treated by CBT-only therapists was M = 1.94, SD = 1.16 (range 1–4) for a total of 35 Ps, by ACT-only therapists was M = 1.89, SD = 1.05 (range 1–4) for a total of 17 Ps, and by therapists who treated in both conditions was M = 6.82, SD = 1.60 (range 4–9) for a total of 75 Ps. The mean patient number for therapists treating in both conditions was significantly higher than the mean for ACT- or CBT-only therapists, ps < .001, pη2= .77 for each comparison; there were no differences between ACT- and CBT-only therapists. This is because therapists were allowed to gain training in the second treatment modality (e.g., in CBT if they started out in ACT) only if they had seen at least several patients in their original modality (e.g., in ACT). Consequently, therapists who treated in both conditions treated more overall Ps. We tested the possibility, therefore, that therapists treating in different conditions evidenced systematic differences in competency that impacted study findings, see Results, below.

Weekly, hour-long group supervision for study therapists was led separately by the principal authors of the treatment manuals and by advanced therapists from UCLA and from Dr. Hayes’ laboratory at the University of Nevada, Reno, where ACT was originally developed. All sessions were videotaped for supervision purposes with a hidden video camera; sessions were also audiotaped for therapy adherence purposes with a discrete digital recorder. Videos were generally played in supervision sessions or watched beforehand by supervisors. ACT supervision occurred by phone and Skype with offsite supervisors supplemented by occasional face-to-face sessions whereas CBT supervision was face-to-face. All therapists completed extensive training including an intensive 3-day workshop with the principal treatment manual author (author M.G.C. for CBT, and author G.E. or Dr. Hayes for ACT) prior to treating Ps. ACT and CBT manuals were matched on the number of sessions devoted to exposure but differed in coping skills and the framing of the intent of exposure.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT for anxiety disorders followed a protocol authored by Craske (2005), which involved a single manual with branching mechanisms that listed cognitive restructuring and behavioral exposure content for each anxiety disorder. Session 1 focused on assessment, self-monitoring, and psychoeducation. Sessions 2–4 emphasized cognitive restructuring with hypothesis testing, self-monitoring, and breathing retraining. Exposure (e.g., interoceptive, in-vivo, and imaginal) was tailored to the principal diagnosis and focused on empiricism and anxiety reduction over time was introduced in Session 5, and emphasized strongly in Sessions 6–11. Session 12 focused on relapse prevention.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

ACT for anxiety disorders followed a manual authored by Eifert and Forsyth (2005). Session 1 focused on psychoeducation, experiential exercises and discussion that introduced acceptance, creative hopelessness, and valued action. Creative hopelessness involved a process of exploring whether efforts to manage and control anxiety had “worked” and experiencing how such efforts had led to the reduction or elimination of valued life activities. Ps were encouraged to behave in ways that enacted their personal values (“valued action”), rather than spend time managing anxiety. Acceptance was explored as an alternative to controlling anxiety. Sessions 2–3 further explored creative hopelessness and acceptance. Sessions 4 and 5 emphasized mindfulness, acceptance and cognitive defusion, or the process of experiencing anxiety-related language (e.g., thoughts, self-talk, etc.) as part of the broader, ongoing stream of present experience rather than getting stuck in responding to its literal meaning. Sessions 6–11 continued to hone acceptance, mindfulness, and defusion, and added values exploration and clarification with the goal of increasing willingness to pursue valued life activities. Behavioral exposures, including interoceptive, in-vivo, and imaginal, were employed as needed to provide opportunities to practice making room for, mindfully observing, and accepting anxiety (all types of exposure) and to practice engaging in valued activities while experiencing anxiety (in-vivo exposures). Session 12 reviewed what worked and how to continue moving forward. See supplementary materials for additional details.

Outcome measures

Because CBT emphasized symptom reduction whereas ACT emphasized broader aims of psychological flexibility and valued living, we investigated two sets of primary outcomes across both treatments: anxiety specific (i.e., symptom reduction related) and non-anxiety specific, or broader outcomes. For the anxiety-specific measures, we included the severity of each principal disorder. In addition, the mixed anxiety disorder nature of our sample required utilization of anxiety-specific outcome measures that were relevant across the anxiety disorders. We selected measures of worry, fear, and behavioral avoidance, features that characterize all anxiety disorders (Craske et al., 2009), and empirically tested them to ensure that they changed following treatment across the entire sample (not merely within a single disorder). For the non-anxiety specific, broader measures we assessed quality of life and psychological flexibility.

Anxiety-Specific Primary Outcomes

Diagnostic Interview Assessment

Clinical diagnoses were ascertained using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-IV (ADIS-IV) (Brown, DiNardo, & Barlow, 1994). Doctoral students in clinical psychology or research assistants served as interviewers after completing 15–20 hours of training and demonstrating adequate diagnostic reliability on 3 consecutive interviews. ‘Clinical severity ratings’ (CSR) were made for each disorder by group consensus on a 0 to 8 scale (0=none, 8=extremely severe). Ratings of “4” or higher indicated clinical significance based on symptom severity, distress and disablement, and served as the cutoff for study eligibility (see Craske et al., 2007). ADIS-IV interviews were audio-recorded and 15% (n = 22) were randomly selected for blind rating by a second interviewer.6 Inter-rater reliability on the principal diagnosis was 100%. Inter-rater agreement on dimensional CSR ratings was .65 with a single-measure, one-way mixed intraclass correlation7 coefficient across the anxiety disorders. Inter-rater agreement for each specific disorder (met DSM-IV criteria vs. subclinical vs. none) was as follows: SAD (10 subclinical or clinical cases) and OCD (3 cases) ICC = 1.00 (100% agreement), PD/A (11 cases) ICC = .91, GAD (8 cases) ICC = .85, and SP (7 cases) ICC = .75.

The Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI; Peterson & Reiss, 1992; Reiss, Peterson, Gursky, & McNally, 1986)8 assesses fear of anxiety-related sensations (e.g. shortness of breath) based on the belief that such sensations are harmful. Although particularly elevated in panic disorder (Taylor, Koch, & McNally, 1992), the ASI shows elevation across most anxiety disorders (Rapee, Brown, Antony, & Barlow, 1992) relative to nonanxious controls (Peterson & Reiss, 1992). Current sample α’s = .85 (Pre) and .93 (Post). The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990) assesses clinically relevant worry. Although particularly elevated in GAD, the PSWQ shows elevations across all anxiety disorders relative to non-anxious controls (Brown, Antony, & Barlow, 1992). Current sample αs = .90 (Pre) and .93 (Post). The Fear Questionnaire’s (FQ; Marks & Mathews, 1979) Main Target Phobia Scale, a single-item avoidance rating for each P’s “main phobia”, was used as the behavioral avoidance outcome.

Broader (Non-Anxiety Specific) Primary Outcomes

The Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI; Frisch, 1994b) assesses values and life satisfaction across 16 broad life domains and has good test-retest reliability and internal validity (Frisch et al., 2005). Current αs = .86 (Pre) and .84 (Post). The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-16 (AAQ; Bond & Bunce, 2000; Hayes et al., 2004) assesses psychological flexibility (Bond et al., 2011). The AAQ-16 is a 16-item version of the 7- and 9-item AAQ that is hypothesized to be more sensitive to clinical change (Hayes et al., 2004). Both one and two-factor solutions have been fit to the 16-item AAQ (Bond & Bunce, 2000, 2003). Herein, a one-factor scale was used, with higher scores indicating greater psychological flexibility. Current αs were .78 (Pre) and .86 (Post). See supplementary materials for additional psychometrics on primary outcomes.

Secondary Outcomes

Use of Additional Treatment

As a behavioral indication of the degree to which each treatment met clients’ needs, we assessed Ps reported use of additional (non-study-related) psychotherapy and psychotropic medication at Post-12m FU with questions on the ADIS-IV..At each assessment point, we compared groups on the portion of Ps who initiated new, dropped (e.g., among Ps using therapy or medication at the previous assessment point), or were using any form (e.g., either new or continued from the previous assessment) of non-study psychotherapy or psychotropic medication.

Generalization of Treatment Effects

Based on the ADIS interview, co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders (with CSR of 4+) at Post-12mFU were analyzed as an index of the generalization of treatment effects. We examined the number of co-occurring anxiety disorders, the presence of co-occurring mood disorders, and the total number of co-occurring anxiety and mood disorders as indices of the generalization of treatment effects.

Treatment Credibility

Prior to the second therapy session, after the treatment rationale had been fully described, Ps completed a six-item treatment credibility questionnaire adapted from Borkovec and Nau (1972), see Supplementary materials. Total sample α = .94; ACT α = .92 and CBT α = .95.

Treatment Adherence and Therapist competence

Treatment sessions were audiotaped and 143 sessions from 91 participants (50 in CBT, 41 in ACT) were randomly selected for treatment adherence and therapist competency ratings using the Drexel University ACT/CT Therapist Adherence and Competence Rating Scale (DUACRS; McGrath, Forman, & Herbert, in preparation). The treatment adherence items (n = 49) included 5 scales: general therapy adherence (12 items), general behavioral therapy adherence (11 items), cognitive therapy adherence (10 items), ACT adherence (16 items) and a therapist competence (5 items), see Supplementary materials. The first author of the DUACRS (McGrath), who had no involvement with the current study and extensive training in both ACT and CBT, completed adherence ratings. To check treatment integrity, the blind rater (McGrath) noted which of 49 therapist adherence items (e.g., specific therapist behaviors or therapy content) occurred in each 5-minute segment of therapy. Treatment-specific subscale scores (indicating adherence to ACT or CBT) were calculated by dividing the number of segments during which subscale-specific therapist behavior was present (i.e., at least one of the items composing a subscale was coded for that five-minute segment) by the total number of segments in the session, yielding an estimate of the percentage of time spent by the therapist on treatment-specific behavior. The general therapy adherence and general behavioral therapy adherence scales were computed in similar manner. At the end of each recording, therapist competence was rated and the mean of the scale items represented the therapist competency rating for that session.

Statistical analyses

Raw data were inspected graphically; outliers (3SD) were replaced with the next higher value, following the Winsor method (Guttman, 1973), prior to data analysis. In full HLM models (see below), Level 1 and 2 residuals were examined for model outliers and fit, and outliers (3SD) were treated in the Winsor method and on two occasions, eliminated due to particularly strong and uncorrectable influence. Less than 5% of the data were modified or eliminated during outlier correction.

Longitudinal data were analyzed with hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) and hierarchical multiple linear modeling (HMLM) in HLM 6.0 (Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2004). HLM/HMLM random effects models examined within and between group change across time (pre, post, 6m FU, 12m FU) and by condition (ACT and CBT). HLM/HMLM incorporates Ps with missing data by estimating the best fitting model from the data available for each P (Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006). Therefore, for the intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses, all data points for Ps who entered treatment were entered into the model. For Completer results, which are reported when different from ITT results, analyses included Ps who completed treatment and at least one subsequent assessment (Post, 6mFU, 12mFU). In fitting models to the longitudinal data, different variance-covariance structures were assessed starting with the simplest, the HLM compound symmetry model. HLM model fit was compared with multiple HMLM level 1 variance-covariance options (homogenous, heterogeneous, first order autoregressive, unstructured) using restricted log likelihood values (−2LL) in chi-square comparisons (see Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2004). The model with the best fit was selected; if models were not significantly different, the model with the fewest parameters was selected.

In the HLM/HMLM models, assessment time points (Pre, Post, 6mFU, 12mFU) were entered on Level 1, and nested within individuals on Level 2. Demographic and clinical covariates, and Group (dummy coded ACT vs. CBT) were entered on Level 2. Between-group differences focused on group differences in change slopes over time and at Post and 12mFU time points. Due to curvilinear patterns over time, quadratic and cubic time terms were tested on Level 1 and kept in final models if they were significant and significantly reduced model deviance (−2LL) according to chi-square based model comparisons. Cubic terms were fixed in order to not overestimate the model’s random effects. For analyses of non-CSR outcomes, pre-CSR was covaried on the intercept to account for pre-treatment diagnostic severity. Effect sizes for within-group change at each assessment point were examined in models that included linear and quadratic slopes only for the sake of clarity and brevity and to avoid overinflating within-group linear effect sizes, which can occur when both quadratic and cubic terms are in the model. We computed d effect sizes that accounted for the number of repeated measurement points as needed (Feingold, 2009)9 and used Cohen’s (1988) guidelines for interpretation.

Differences in rate of improvement should translate into different outcomes at post-treatment or follow up. Therefore, the Post and 12mFU time points represented our main time points of interest for examining cross sectional group differences.

For comorbidity analyses, we compared groups at Pre using chi-square and over time using repeated measures GHLM random effects repeated measure models (see Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, et al., 2004), which utilize Ps with incomplete data.

Three separate indices examined treatment response in terms of the percent of responders at each assessment point (Post, 6mFU, 12mFU); chi-square analyses examined between group differences. Diagnostic status improvement was defined in accordance with recent clinical trials (Newman et al., 2011; Roemer et al., 2008) as a principal diagnosis CSR of 3 or below. Reliable change was computed using the Jacobson & Truax (1991) method, using the more conservative denominator recommended by Maassen (2004). To remain consistent with previous randomized clinical trials, we focused the response indices on anxiety-specific outcomes. Due to the range of principal disorders and conservative method of defining change, we examined group differences in reliable change on at least 2/4 anxiety-specific primary outcomes (reliable change status), as well as reliable change plus falling within 1 SD of the nonclinical normative range (or 3 or less on CSR) on at least 2/4 anxiety-specific primary outcomes (high end state functioning status), and reliable change on the principal disorder CSR plus CSR of 3 or below (diagnostic change status) (e.g., Newman et al., 2011; Roemer et al., 2008). See supplementary materials for employed norms and computations details, and Table 6 for reliable change critical values.

Table 6.

Response Rates on Treatment Response Indices

| Shows reliable change1 on at least 2 of 4 anxiety-specific outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | CBT | ACT | χ2 | p | Cramer’s v |

| Post-treatment | 44.4% (16/36) | 56.7% (17/30) | .98 | .32 | .12 |

| 6-month | 53.6% (15/28) | 47.1% (8/17) | .09 | .76 | .05 |

| 12-month | 52.2% (12/23) | 52.6% (10/19) | .00 | .98 | .01 |

| Shows reliable change1 and High endstate functioning based on 2 of 4 anxiety-specific outcomes | |||||

| Assessment | CBT | ACT | χ2 | p | Cramer’s v |

|

| |||||

| Post-treatment | 47.2% (17/36) | 50.0% (15/30) | .05 | .82 | .03 |

| 6-month | 53.6% (15/28) | 47.1% (8/17) | .18 | .67 | .06 |

| 12-month | 39.1% (9/23) | 47.4% (9/19) | .29 | .59 | .08 |

| Shows reliable CSR change1 and Does not meet clinical diagnostic criteria (CSR ≤ 3) | |||||

| Assessment | CBT | ACT | χ2 | p | Cramer’s v |

|

| |||||

| Post-treatment | 51.0% (25/49) | 44.7% (17/38) | .34 | .56 | .06 |

| 6-month | 59.5% (22/37) | 44.4% (12/27) | 1.41 | .24 | .15 |

| 12-month | 50.0% (16/32) | 54.5% (12/22) | .11 | .74 | .05 |

Reliable change required the following minimum improvement values from pre-treatment (see Supplementary Materials for computational details): principal disorder clinical severity rating (CSR) = 2.75, Penn State Worry Questionnaire = 10.03, Anxiety Sensitivity Index = 10.48, Fear Questionnaire Main Target Phobia Avoidance Rating = 1.97.

To assess if data were missing at random, we conducted chi-square comparisons on primary outcomes comparing Ps who dropped out vs. finished treatment, and treatment finishers with complete vs. incomplete data at 6mFU and 12mFU. For dropouts vs. finishers, no significant differences emerged at Pre on any primary outcome variable. For treatment finishers with complete vs. incomplete data, no significant differences emerged at Pre or Post, with the minor exception that Ps with incomplete FU data had higher ASI scores at Pre (p = .04, pη2 =.05) but not at Post. The findings suggest that the data were missing at random.

Power analyses, conducted in Optimal Design (see Raudenbush & Liu, 2000), indicated that to reach 80% power, a cross sectional between-group difference (e.g., at 12mFU) with an effect size of .70 required 67 total Ps, whereas a between-group effect size of .50 required 126 total Ps. Therefore, our total sample size (n = 128) was sufficient to detect between group differences of moderate size at each assessment point.

RESULTS

Pre-treatment Group Differences

At pre-treatment, ACT and CBT evidenced no significant differences on anxiety specific or broader outcome measures, although ASI differences approached significance, t(111) = 1.91, p = .058 (all other outcome ps > .2). Further, ACT (8.82%, 3/34) and CBT (9.68%, 3/31)10 showed no differences in use of non-study psychotherapy at Pre, χ2 = .01, p = .91, nor in use of psychotropic medication, see Table 1. ACT and CBT showed no significant differences on socio-demographic or clinical characteristics in Table 1 with one exception. Despite randomization procedures, there was a trend for higher rates of a principal diagnosis of PD/A in CBT (49.3%) than in ACT (32.1%), χ2 = 3.79, p = .052. In HLM analyses, principal PD/A diagnosis predicted superior CSR outcomes compared to non-PD/A principal diagnoses, at Post (B = −1.14, SE = .45, t(126) = −2.53, p = .01, d = 1.31) and 6mFU (B = −1.01, SE = .51, t(126) = −2.11, p = .04, d = 1.16), but not at 12mFU (B = −.62, p = .26). Despite the significant impact of PD/A on CSR outcomes, we did not covary PD/A in further HLM/HMLM analyses to avoid further stratification of Ps into additional subgroups that lacked apriori significance and to avoid reduced statistical power to examine our principal comparison of CBT versus ACT. Principal PD/A did not predict other primary outcomes for which we found significant CBT versus ACT differences.

Treatment Credibility

Treatment credibility scores (immediately prior to Session 2) differed significantly by Group, F(1, 76) = 9.08, p= .004, pη2 = .11, with CBT evidencing higher scores (M = 6.08, SD = 1.44, n = 51) than ACT (M = 4.92, SD = 1.91, n = 27). Missing treatment credibility data from the first 24 ACT participants11 resulted in a lower n in this group. When the first 24 CBT participants were excluded from analyses, group differences held: F(1, 62) = 6.34, p = .01, pη2=.09, with CBT again showing significantly higher scores (M = 6.00, SD = 1.53, n = 37) than ACT (M = 4.92, SD = 1.91, n = 27).

Therapist competence and Treatment Integrity

Therapist competency scale scores (e.g., “knowledge of treatment”, “skill in delivering treatment”, and “relationship with client”; 1=poor, 3=good, 5=excellent) indicated “good” therapist skills in CBT (M = 3.08, SD = .64) and ACT (M = 3.25, SD = .77). ACT therapists and CBT therapists did not significantly differ on competency ratings F(1,77) = 1.17, p = .28, pη2 = .02.

Cognitive therapy adherence scores were higher for CBT (M=62.23, SD = 18.07) than ACT (M = 5.03, SD = 9.83), F(1, 87) = 316.88, p < .001, pη2 = .76. Conversely, ACT adherence scores were higher for ACT (M = 82.26, SD = 18.04) than CBT (M = 3.94, SD = 6.40), F(1, 87) = 813.58, p < .001, pη2 = .90. On the behavioral adherence scale, CBT (M = 47.41, SD = 23.59) scored significantly higher than ACT (M = 25.35, SD = 18.83), F(1, 87) = 22.77, p < .001, pη2 = .21, however, this scale included a range of behavioral items such as therapist modeling that are more commonly used in CBT. We explored group differences on behavioral exposure-related items from the behavioral adherence scale; differences between CBT (M = 14.25, SD = 18.34) and ACT (M = 8.01, SD = 11.77) on behavioral exposure items, p = .07 pη2 = .04 did not reach full significance. The general therapy adherence scale did not differ significantly between CBT (M = 96.89, SD = 9.86) and ACT (M = 99.10, SD = 4.27), F(1, 87) = 1.72, p = .19, pη2 = .02. The combined results show that therapists exhibited strong adherence to their assigned treatment.

To test the possibility that therapists treating in different conditions varied in competence, we compared CBT-only, ACT-only, and both-type (e.g., treated Ps in both CBT and ACT) therapists on competence. CBT-only (M = 2.96, SD = .64) and ACT-only therapists (M = 3.02, SD = .62) showed no differences in competence (p = .81), nor did ACT-only and both-type therapists (p = .13). Both-type therapists, however, showed significantly higher competence (M = 3.36, SD = .72) than CBT-only therapists (M = 2.96, SD = .64), F (1, 73) = 5.18, p = .03, pη2 = .07. To determine if therapists who treated in a single condition impacted study findings, we reran the CSR analyses twice, once without CBT-only therapists and once without CBT- and ACT-only therapists. Although reduced power from lower n (which meant the analyses fell below the 80% statistical power level) meant that group differences were not statistically significant, the pattern of findings for group differences matched those reported for the full sample below, suggesting that therapist assignment did not impact study findings. See supplementary materials for an example of these results.

Treatment Attrition

Eighty-five of 128 Ps (66%) completed the full 12 sessions of therapy, including 68% (48/71) in CBT and 65% (37/57) in ACT. The additional 43 Ps (34%) received a partial dose of therapy: 13 Ps attended 1 session (5 ACT, 8 CBT) and 30 Ps (15 in each ACT and CBT) attended 2 to 11 therapy sessions. The portion of Ps who did not complete the full 12 sessions did not differ by Group, χ2(1)= .40, n.s. Finally, the total number of treatment sessions attended by the ITT sample did not differ by Group; CBT M = 9.62 (SD = 4.08), ACT M = 9.37 (SD = 4.05), F(1, 126) = .12, p = .73, pη2 = .00.

Primary Outcomes

Table 2 provides the means and SDs for primary outcomes at each assessment point. We conducted separate ITT and treatment completer analyses. Completer analyses are reported when they differ in significance or effect size from the ITT analyses. Effect sizes for within-group and between-group change are listed by group in Table 3. Table 4 provides the means, SDs, effect sizes, and diagnostic response rates for primary outcomes at Post for each anxiety disorder. Individual disorder outcomes were not analyzed or discussed further, however, because we did not design or power this study to examine group differences in outcomes for individual anxiety disorders.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations for primary outcomes at each assessment point

| Measure and condition | Pre-treatment M (SD) |

Post-treatment M (SD) |

6-month M (SD) |

12-month M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Anxiety-Specific Outcomes | ||||

|

| ||||

| Clinician’s Severity Rating | ||||

| ACT | 5.70 (.89) | 3.11 (2.21) | 2.77 (2.39) | 2.33 (1.98) |

| CBT | 5.55 (.94) | 2.90 (2.12) | 2.67 (2.24) | 2.94 (2.52) |

|

| ||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity Index | ||||

| ACT | 31.81 (11.25) | 18.65 (11.89) | 14.56 (10.14) | 17.05 (12.62) |

| CBT | 27.60 (11.81) | 18.68 (11.16) | 20.47 (12.90) | 15.64 (8.04) |

|

| ||||

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire | ||||

| ACT | 46.52 (11.93) | 39.89 (11.01) | 37.79 (10.87) | 39.32 (12.26) |

| CBT | 45.00 (12.82) | 37.63 (15.22) | 37.72 (13.04) | 37.14 (12.72) |

|

| ||||

| Fear Questionnaire (avoidance) | ||||

| ACT | 5.84 (2.34) | 4.13 (2.37) | 4.00 (2.66) | 4.28 (2.72) |

| CBT | 5.34 (2.95) | 4.06 (2.96) | 4.22 (3.12) | 3.82 (2.70) |

|

| ||||

| Broader Outcomes | ||||

|

| ||||

| Quality of Life Index | ||||

| ACT | .19 (1.85) | 1.42 (1.88) | .50 (1.43) | 1.17 (1.51) |

| CBT | .55 (2.10) | 1.78 (1.35) | 1.45 (1.52) | 1.86 (1.88) |

|

| ||||

| Acceptance and Action-16 | ||||

| ACT | 59.01 (12.35) | 70.82 (13.14) | 72.14 (10.86) | 71.71 (11.42) |

| CBT | 58.49 (11.84) | 69.43 (14.75) | 68.38 (13.76) | 68.43 (11.65) |

Table 3.

Effect sizes (d) of Within and Between Subject Effects for Primary Outcomes

| Outcomes: | ACT | CBT |

Between Groups |

ACT | CBT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Specific | ||||||

| CSR | ||||||

| Linear Pre-Post | −3.74 | −3.46 | 0.26 | Quadratic: β | 0.71 | 0.73 |

| Linear Post-FU | −1.98 | −1.78 | 0.32 | Quadratic: effect size (d) | 0.82 | 0.84 |

| Linear 6–12m FU | −0.46 | −0.08 | 0.38 | |||

| ASI | ||||||

| Linear Pre-Post | −1.18 | −0.63 | 0.55 | Quadratic: β | 3.08 | 1.39 |

| Linear Post-FU | −0.65 | −0.39 | 0.26 | Quadratic: effect size (d) | 0.26 | 0.12 |

| Linear 6–12m FU | −0.12 | −0.15 | 0.03 | |||

| PSWQ | ||||||

| Linear Pre-Post | −0.74 | −0.64 | 0.11 | Quadratic: β | 2.00 | 1.64 |

| Linear Post-FU | −0.40 | −0.36 | 0.05 | Quadratic: effect size (d) | 0.17 | 0.14 |

| Linear 6–12m FU | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.02 | |||

| FQ | ||||||

| Linear Pre-Post | −0.83 | −0.52 | 0.31 | Quadratic: β | 0.34 | 0.61 |

| Linear Post-FU | −0.38 | −0.27 | 0.11 | Quadratic: effect size (d) | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| Linear 6–12m FU | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.08 | |||

| Non-Anxiety Specific | ||||||

| AAQ (higher scores indicate improvement) | ||||||

| Linear Pre-Post | 1.16 | 0.90 | 0.26 | Quadratic: β | −3.20 | −2.70 |

| Linear Post-FU | 0.63 | 0.45 | 0.18 | Quadratic: effect size (d) | −0.27 | −0.22 |

| Linear 6–12m FU | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.10 | |||

| QOLI (higher scores indicate improvement) | ||||||

| Linear Pre-Post | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.00 | Quadratic: β | −0.15 | −0.21 |

| Linear Post-FU | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.06 | Quadratic: effect size (d) | −0.08 | −0.11 |

| Linear 6–12m FU | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |||

Notes: For the sake of clarity, effect sizes reflect HLM models with linear and quadratic time terms only. Quadratic terms are invariant across assessment points.

CSR = ADIS-IV principal disorder clinical severity ratings; ASI = Anxiety Sensitivity Index; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; FQ = Main Target Phobia Scale (behavioral avoidance rating) from the Fear Questionnaire; AAQ = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire; QOLI = Quality of Life Inventory

Table 4.

Means and standard deviations for primary outcomes by disorder

| Anxiety Disordera and Measure | Pre M (SD) |

Postb M (SD) |

6mFUb M (SD) |

12mFUb M (SD) |

Linear/Quadratic d effect size for Pre-Postc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Panic disorder with or without Agoraphobia | |||||

|

| |||||

| Clinician’s Severity Rating | |||||

| ACT (n = 18 Pre) | 5.56 (.78) | 2.40 (2.27) | 2.00 (2.74) | 2.00 (2.08) | −4.24/.93 |

| CBT (n = 35 Pre) | 5.57 (.88) | 2.22 (2.15) | 2.59 (2.45) | 2.58 (2.84) | −4.02/1.02 |

|

| |||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity Index | |||||

| ACT (n = 17 Pre) | 37.29 (6.73) | 25.56 (12.39) | 26.67 (12.42) | 23.60 (14.12) | −.98/.19 |

| CBT (n = 33 Pre) | 32.03 (9.57) | 17.63 (10.87) | 18.72 (8.96) | 15.29 (8.88) | −1.31/.32 |

|

| |||||

| Social Anxiety Disorder | |||||

|

| |||||

| Clinician’s Severity Rating | |||||

| ACT (n = 13 Pre) | 5.46 (.88) | 4.33 (1.73) | 3.43 (2.07) | 2.60 (2.07) | −.93 |

| CBT (n = 12 Pre) | 5.75 (1.14) | 3.56 (1.24) | 3.33 (1.32) | 4.00 (2.00) | −.59 |

|

| |||||

| FQ- Social Phobia Subscale | |||||

| ACT (n = 11 Pre) | 17.45 (9.78) | 16.63 (7.60) | 14.80 (9.68) | 17.20 (9.52) | −.56/.19 |

| CBT (n = 10 Pre) | 20.60 (11.01) | 14.67 (8.26) | 14.67 (6.67) | 17.86 (6.96) | −54/.16 |

|

| |||||

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | |||||

|

| |||||

| Clinician’s Severity Rating | |||||

| ACT (n = 14 Pre) | 6.07 (.73) | 1.80 (1.69) | 1.75 (2.19) | 2.00 (1.55) | −5.70/1.47 |

| CBT (n = 12 Pre) | 5.25 (.97) | 3.00 (2.45) | 0.00 (.00) | 1.50 (3.00) | −2.97/.58 |

|

| |||||

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire | |||||

| ACT (n = 12 Pre) | 50.50 (10.83) | 35.26 (8.81) | 35.17 (5.64) | 36.09 (17.64) | −.58 |

| CBT (n = 11 Pre) | 52.14 (10.34) | 42.43 (14.65) | 37.20 (13.81) | 40.75 (12.09) | −.25 |

|

| |||||

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | |||||

|

| |||||

| Clinician’s Severity Rating | |||||

| ACT (n = 9 Pre) | 5.67 (1.23) | 4.00 (2.24) | 4.00 (2.74) | 2.00 (2.83) | −2.67/.52 |

| CBT (n = 8 Pre) | 5.88 (.84) | 5.00 (1.58) | 4.50 (2.38) | 3.50 (2.52) | −1.03/.15 |

|

| |||||

| PI-WSUR | |||||

| ACT (n = 7 Pre) | 36.69 (17.61) | 37.50 (24.37) | 28.25 (18.95) | 26.98 (13.69) | −.07 |

| CBT (n = 5 Pre) | 40.60 (23.93) | 27.25 (11.47) | 35.00 (22.63) | 28.00 (18.38) | −.25 |

We did not compute separate means or standard deviations for specific phobia Ps because of their low numbers (n = 6).

These represent the mean and standard deviation for Ps with data at each assessment point.

For ease of comparison with full-sample data reported in Table 3, we employed the pooled SD from the entire sample as the denominator in the Feingold (2009) effect size magnitude formula. This resulted in somewhat more conservative (lower) effect sizes for some measures.

Primary Outcomes Change Slopes: ITT

Anxiety Specific Outcomes

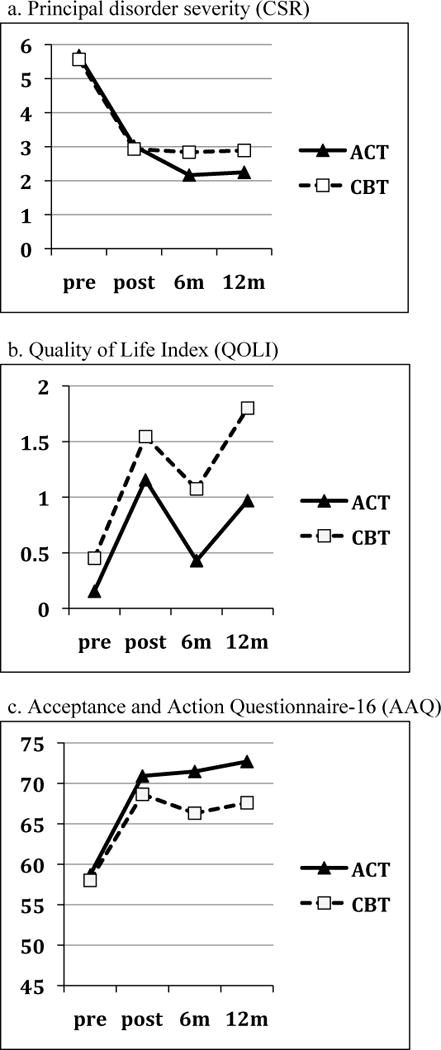

With the intercept (0) representing Pre, the HLM ITT model for CSR outcomes showed significant effects of linear, quadratic and cubic change over Time, all ps <.001, but no significant Group × Time interactions. However, after treatment, the groups showed significant differences in CSR linear slope (within the full model accounting for Group on higher order change terms) such that ACT continued to improve from Post to 12mFU, whereas CBT maintained but did not continue to improve as much, B = .58, SE = .28, t(126) = 2.03, p = .04, d = 1.33 (effect size of group difference from Post to 12mFU), see Figure 2a. The CSR slopes after treatment were best fit within a HMLM unrestricted covariance model.

Figure 2.

a–c. Primary outcomes in the ITT sample with ACT vs. CBT differences

The HLM ITT model for ASI, PSWQ, and FQ outcomes showed significant effects of linear, quadratic, and cubic change over Time, all ps <.01, but no significant Group × Time interactions from pre- to post-treatment, or after treatment.

Broader Outcomes

The HLM ITT models for AAQ and QOLI outcomes showed significant effects of linear, quadratic, and cubic change over Time, all ps ≤ .001, but no significant Group × Time interactions from pre- to post-treatment, or after treatment.

Primary Outcomes Change Slopes: Completers

Anxiety Specific Outcomes

Completers evidenced a similar but smaller Group × Linear slope interaction for CSR after treatment, B = .43, SE = .21, t(77) = 2.05, p = .04, d = .90, favoring ACT. A HMLM homogenous covariance structure best fit the data.

Primary Outcomes at Post: ITT Sample

Anxiety Specific and Broader Outcomes

At Post, ACT and CBT did not differ significantly on any anxiety specific measure or broader outcome measure.

Primary Outcomes at 12mFU: ITT Sample

Anxiety Specific Outcomes

At 12mFU, ACT and CBT did not differ on any anxiety specific measure.

Broader Outcomes

At 12mFU, CBT demonstrated higher QOLI ratings than ACT, B = .83, SE = .41, t(113) 2.05, p = .04, d = .43, see Figure 2b. In addition, group differences in AAQ approached significance, B = 5.10, SE = 2.86, t(117) = 1.78, p = .08, d = .42, with ACT showing greater psychological flexibility than CBT, see Figure 2c. An HLM covariance structure was the best fit for 12mFU outcomes.

Primary Outcomes at 12mFU: Completer Sample

Anxiety Specific Outcomes

ACT was assigned significantly lower CSR ratings for the principal anxiety disorder than CBT, B = 1.01, SE = .49, t(83) = 2.04, p = .04, d = 1.0512. A homogenous level 1 variance HMLM model best fit the CSR data. At this assessment point (12mFU), PD/A status was unrelated to CSR outcomes (see Results, above), bolstering the significance of this finding. The groups did not differ significantly on the ASI, PSWQ or FQ.

Broader Outcomes

CBT showed higher QOLI values than ACT, B = .68, SE = .32, t(65) = 2.12, p = .03, d = .36. ACT showed significantly higher AAQ scores than CBT, B = 6.76, SE = 2.65, t(66) = 2.65, p = .01, d = .59.

Secondary Outcomes

Use of Additional Psychotherapy and Medication

There were no group differences at Post, 6mFU or 12mFU in use of new or any (e.g., new or continued) psychotropic medication, all ps > .44, see Supplementary materials. For dropped medication, there was no group difference at 6mFU, p > .69, with n’s at 12mFU too small to compare. At Post, however, CBT resulted in borderline greater dropped medication than ACT, B = 2.13, SE = 1.10, p = .05 (p = .053), Exp(B) = 8.42 (95% CI: .97 to 73.06), with 37.04% (10/27) of CBT versus 7.14% (1/14) of ACT Ps dropping medication from Pre to Post. Because there were no group differences in overall medication use at Post (p = .86), however, we did not further analyze this borderline significant finding.

The groups did not differ in new, dropped, or any outside psychotherapy use at either Post or 12mFU, ps > .26. At 6mFU, groups did not differ on new (p = .13) psychotherapy, however, ACT reported greater use of any psychotherapy (e.g., new or continued) than CBT, B = 1.29, SE = .63, Wald (1) = 4.28, p = .04, Exp(B) = 3.65 (95% CI: 1.07 to 12.42): 39% (11/28) of ACT Ps versus 19% (5/27) of CBT Ps. To explore the clinical impact of this finding, we reran the CSR analyses dropping the Ps who reported any psychotherapy use at 6mFU, and found that the results followed the same pattern as the ITT analysis reported above. Further, we assessed whether psychotherapy use at 6mFU predicted principal diagnosis CSRs at 6mFU or 12mFU and found that it did not (ps > .4 for both ACT and CBT). Given these two sets of null findings, additional psychotherapy at 6mFU was not covaried in subsequent analyses. Exploratory analyses showed, however, that ACT patients who remained severe (CSR 4+) following treatment were somewhat more likely to seek additional treatment than CBT patients that remained severe, p = .07, see Supplementary materials.

Generalization of Treatment Effects

The groups did not differ significantly in the number of co-occurring anxiety, mood, or anxiety and mood disorders combined at Pre, ps >. 18. Nor did the groups differ significantly in rates of reduction of co-occurring disorders over Time, with both groups showing decreases in co-occurring disorders following treatment, see Table 5.

Table 5.

Co-occurring disorders: Rates and improvement among Ps with data at each time point

| % of Ps with co-occurring disorders | ACT | CBT | Between Group χ2 | ACT: ∆ slope over time (odds ratio)1` | CBT: ∆ slope over time (odds ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Treatment | |||||

| Anxiety Disorders | 39.3% (22/56) |

28.2% (20/71) |

p=.19 | ||

| Mood Disorders | 23.2% (13/56) |

23.9% (17/71) |

p=.92 | ||

| Mood or Anxiety | 52.8% (29/56) |

41.2% (28/68) |

p=.24 | ||

| Posttreatment | |||||

| Anxiety Disorders | 10.8% (4/37) |

8.7% (4/46) |

p =.75 | .38*** (CI: .24, .59) |

.47** (CI: .29, .78) |

| Mood Disorders | 8.1% (3/37) |

2.2% (1/46) |

p=.21 | .43** (CI: .23, .83) |

.36** (CI: .17, .76) |

| Mood or Anxiety | 18.9% (7/37) |

8.7% (4/46) |

p=.17 | .41*** (CI: .26, .63) |

.44** (CI: .26, .75) |

| 6m FU | |||||

| Anxiety Disorders | 7.7% (2/26) |

5.6% (2/36) |

p=.85 | ||

| Mood Disorders | 3.8% (1/26) |

2.8% (1/36) |

p=.85 | ||

| Mood or Anxiety | 11.5% (3/26) |

5.6% (2/36) |

p=.77 | ||

| 12m FU | |||||

| Anxiety Disorders | 5.9% (1/17) |

7.4% (2/27) |

p=.85 | ||

| Mood Disorders | 5.9% (1/17) |

7.4% (2/27) |

p=.85 | ||

| Mood or Anxiety | 11.8% (2/17) |

14.8% (4/27) |

p=.77 |

Within group

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

The odds ratios are based on fixed GHLM linear time slopes for within-group change over time for dichotomous outcomes, covarying pre-treatment CSR for the principal diagnosis at the model’s intercept. They are reported here at post-treatment but characterize the linear change rate over the pre-treatment to 12m FU period.

Treatment Response Rates

The groups did not significantly differ in treatment response rates, see Table 6.

DISCUSSION

Within a randomized clinical trial, we aimed to test the efficacy of ACT relative to a gold standard treatment for anxiety disorders, CBT. Because ACT represents a transdiagnostic treatment approach (Hayes et al., 1999), we focused on a mixed anxiety disorder sample. We explored the degree to which each treatment reduced anxiety symptoms, and tested the hypothesis that ACT would improve measures of quality of life and psychological flexibility to a greater extent than CBT.

Overall, the findings demonstrated that ACT and CBT did not differ significantly at post-treatment on either anxiety specific or broader outcomes. Over the follow up interval, group differences emerged with ACT showing superiority over CBT on principal disorder severity and psychological flexibility outcomes. However, the follow-up group differences are complicated by the fact that significantly more ACT participants utilized outside psychotherapy during the initial followup interval than CBT participants. Our hypothesis that ACT would improve more than CBT on broader outcomes met with limited support; on one broad outcome, ACT improved more than CBT but on the other, CBT improved more than ACT.

Primary Outcomes

On all primary outcomes, ACT and CBT showed substantial improvement from pre- to post-treatment. On anxiety-specific outcomes, within-group linear effect sizes in ACT and CBT from pre- to post-treatment ranged from very large for principal disorder severity (CSR) to moderate or large for other anxiety outcomes. Thus, both treatments were highly efficacious. Anxiety-related outcomes continued to improve through the six-month follow-up assessment within both ACT and CBT. From six to twelve months, improvement slowed but treatment gains endured. On broader outcomes, both groups showed large improvements in psychological flexibility and more moderate improvements in quality of life at post-treatment. Broader outcomes continue to improve through six-month follow up and gains endured from six to twelve-month follow up. In summary, ACT and CBT resulted in significant improvements from pre- to post-treatment that were maintained or improved upon during follow up, on both anxiety-specific and broader outcomes. Further, improvements were evident across two different dimensions of treatment response, namely, more objective, clinician-rated CSR outcomes as well as subjective, patient-rated self-report outcomes.

From the end of treatment through to the 12-month follow up, several noteworthy group differences emerged. On anxiety-specific outcomes, ACT demonstrated a steeper improvement rate than CBT in the principal disorder severity rating, a difference of large effect size. ACT’s steeper improvement rates resulted in lower principal disorder severity ratings than CBT at the 12 month follow up, again of large effect size, although statistically significant effects were limited to the Completer sample. Over the long term, therefore, ACT more effectively reduced principal anxiety disorder severity than CBT among those who completed treatment. This finding is consistent with a previous study (Lappalainen et al., 2007) that found that ACT resulted in more symptom improvement that CBT, albeit in a much smaller sample (n = 28) of unselected outpatients. However, since more ACT than CBT patients in the current study utilized outside therapy during the initial follow up interval, we cannot fully determine whether ACT’s superiority resulted from the ACT treatment alone or ACT plus additional psychotherapy. Excluding patients using non-study therapy from the principal disorder severity analyses, however, did not change the pattern of results, suggesting that use of non-study therapy did not influence the principal disorder severity findings.

For broader outcomes, one unexpected finding was that CBT participants reported significantly higher quality of life than ACT at 12-month follow up, a difference of moderate effect size. It had been hypothesized that the explicit focus on valued living in ACT would lead to greater improvements in quality of life. Conceivably, our measure of quality of life was too general to capture values-specific improvements. Consistent with hypotheses, however, ACT participants reported higher levels of psychological flexibility than CBT at 12-month follow up on a measure specifically designed to capture ACT-related improvement (Hayes et al., 2004). Please refer to the Supplementary materials for further discussion of primary outcomes.

Finally, ACT and CBT produced similar rates of reliable change, diagnostic improvement, and high end state functioning, comparable to our recent review showing that on average the mean response rate for CBT across anxiety disorder studies from 2000–2011 was 51.36% at post-treatment (180 studies) and 54.80% at follow-up (71 studies) (Loerinc, Meuret, Twohig, Rosenfield, & Craske, in submission). Very few studies (of the 180) used reliable change index methods to compute treatment response rates but the few that did (e.g., Addis et al., 2004; Carter, Sbrocco, Gore, Marin, & Lewis, 2003) evidenced response rates comparable to those in the present study.

Secondary outcomes

As noted above, more ACT than CBT patients reported non-study psychotherapy (new or continued psychotherapy) at the 6-month follow-up assessment, although there were no group differences in the initiation of new psychotherapy during this period nor in medication use, nor any group differences on these variables at 12-month follow up. Reasons for this group difference, nonetheless, were explored. The data showed some support for the notion that ACT patients who remained distressed following treatment were more likely to seek additional psychotherapy than CBT patients who remained distressed. Another possibility is that the broader focus on exploring personal values, pursuing meaningful life behaviors, and contacting the full range of emotions in ACT inspired patients to continue engaging in psychotherapy.

Both ACT and CBT resulted in robust reductions in co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders. This finding demonstrates that treatment effects generalized in both groups, replicating and extending previous work on the broader effects of CBT for panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder (e.g., Borkovec, Abel, & Newman, 1995; Tsao, Mystkowski, Zucker, & Craske, 2005).

Treatment and Therapist Variables

Attrition rates were relatively high across both ACT and CBT; however, no group differences emerged. Attrition was comparable to some large trials of CBT for anxiety disorders (e.g. Barlow et al., 2000) but was higher than the mean attrition (23%) reported in a meta-analysis of CBT studies for anxiety disorders (Hofmann & Smits, 2008). Although attrition reasons for many patients remain unknown, we suspect that four features of our study may have contributed to attrition. First, the study took place in a difficult to locate, high-traffic, parking-challenged clinic with limited public transportation options, and travel times to and from treatment often exceeded 45 minutes each way. Second, our assessments included a 2 to 3 hour physiological laboratory session that was strongly anxiety provoking for many patients (e.g. involving hyperventilation, negative picture slide viewing, etc.), which may have discouraged patients from study completion. Third, unlike many studies where treatment is free or low cost for all, most patients paid for treatment, and incurred significant parking costs. Fourth, we offered few incentives for treatment completion and failed to sufficiently incentivize post-treatment and follow-up assessment completion. Higher incentives may have been particularly needed in a study with such significant treatment barriers (e.g., long travel times, parking fees and difficulties, treatment fees, etc.).

An important finding to emerge from blind treatment integrity ratings was that ACT and CBT were clearly distinguished from one another and that therapists strongly adhered to the designated treatment. Despite the use of novice student therapists, therapists averaged “good” overall skills across both treatments with no differences between treatment groups. Therapists treating patients in both CBT and ACT nonetheless evidenced significantly higher competence than therapists treating in CBT only. Principal diagnostic severity analyses of patients treated only by “both-type” therapists showed the same pattern of outcomes, however, suggesting that these differences did not impact overall study findings.

Early in treatment, CBT was rated as a more credible treatment than ACT by a medium effect size. Thus, ACT therapists were not as successful as CBT therapists in convincing patients early on that they offered a credible treatment. This difference did not appear to influence attrition rates, which did not differ by group. Conceivably, abstract ideas of acceptance and creative hopelessness in initial ACT sessions (rather than concrete skills in CBT) contributed to a diminished sense of treatment credibility. Future studies should assess treatment credibility regularly throughout ACT to determine whether ACT follows a delayed trajectory in convincing patients that it offers something credible, or whether ACT patients remain skeptical throughout treatment but improve anyway. The latter would suggest that treatment credibility is relatively unimportant to the success of ACT. Certainly, in the current study, the lowered credibility ratings relative to CBT did not appear to disadvantage ACT outcomes relative to CBT outcomes.

Study Limitations

Several study limitations should be noted. First, our mixed anxiety disorder sample limits the conclusions that may be drawn about any single anxiety disorder. Anxiety disorders typically co-occur at high rates with other anxiety disorders and share many common features (see Barlow, 2002; Craske et al., 2009), however, strengthening the ecological validity of this approach. Second, relatively high attrition rates may have resulted in underestimated treatment effects or compromised ability to accurately assess treatment-related improvements in the ITT sample. On the other hand, we utilized a sophisticated statistical approach (HLM, HMLM) that utilized patients with incomplete data and drew upon all available data in the ITT analyses; we also conducted a separate Completers analyses. Third, we did not assess therapist allegiance, which may have impacted treatment results given that the study was conducted within a CBT-renowned research clinic. Based on the relatively inexperienced and junior nature of the therapists, however, allegiance is unlikely to be a significant factor. Therapist experience raises another limitation, which is that the results may differ in the hands of more experienced therapists. Fourth, CBT supervision was conducted onsite in a face-to-face manner whereas most ACT supervision was conducted via phone or Skype with offsite supervisors. We did not assess supervision quality and thus could not investigate the impact of this group difference. Fifth, we did not systematically assess reasons for attrition, and thus could not assess whether ACT and CBT differed in the extent to which patients dropped out because they were unsatisfied with treatment. Future ACT/CBT studies should assess group differences in stated reasons for attrition. Sixth, we utilized a single item rating from the Fear Questionnaire for behavioral avoidance due to the lack of avoidance measures relevant to all anxiety disorders. Seventh, we used a website to generate the randomization sequence whereas use of an external agency would have been preferable. Eighth, we did not include a no-treatment or treatment-as-usual control group, which may have obscured our capacity to assess improvement due to treatment versus the passage of time. It has been argued, however, that comparing a newer to a well-established treatment does not require a no-treatment or waitlist control group and is more ethical without one (Kazdin, 2002). Also, the roughly equal number of treatment sessions devoted to behavioral exposure in ACT and CBT may have obscured treatment differences. The two treatment conditions were matched on exposure, albeit framed with different intents, given the potency of exposure as a change agent. This feature may have altered the way that ACT is typically done. In addition, the Penn State Worry Questionnaire scores at pre-treatment in the GAD subsample were considerably lower that those in recently published randomized trials for GAD (Newman et al., 2011; Roemer et al., 2008), which may hold implications for the interpretation of findings in this subgroup. Finally, regarding the generalizability of our findings, our sample largely reflected the racial, ethnic, and sex distribution of U.S. residents at the time of data collection (Bureau, 2012), supporting the broad generalizability of our findings. On the other hand, our sample was relatively educated (the average participant had completed 3.5 years of college) and thus, our findings may not generalize to less educated samples. Further, we cannot assume that treatment was equally efficacious across racial subgroups because we lacked the statistical power to examine whether outcomes differed by race. This remains an important question for future research.

Summary and conclusion

To our knowledge, this study represents the first randomized clinical trial comparing ACT and CBT for anxiety disorders. Despite differences in underlying treatment models, the overall findings are characterized by similarities in the immediate and long-term impact of both treatments. We have argued elsewhere (Arch & Craske, 2008) that ACT and CBT for anxiety disorders may represent different approaches to affecting common therapeutic changes. This study largely supports this hypothesis. On the other hand, some differences did emerge, in that CBT resulted in higher quality of life whereas ACT resulted in greater psychological flexibility, and, among those who completed treatment, lower principal anxiety disorder severity, over the follow-up. Overall, our findings suggest that ACT is a highly viable psychosocial treatment alternative to CBT, the current gold standard psychosocial treatment for anxiety disorders. Further, they pave the way for future investigations of for whom each treatment approach is most effective, and the shared versus unique mechanisms of therapeutic change.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Daniel Dickson and Milena Stoyanova for study coordination, to John Forsyth for help with initial study planning, and to Chick Judd and Kate Wolitzky-Taylor for sound statistical advice. Thank you to the many research assistants (over one dozen) who assisted in data collection, the many graduate student therapists, and above all, the individuals who participated in the study.

Footnotes

The study called their approach “cognitive therapy” which they defined as the Beck-based treatment subtype of CBT, see Forman et al, 2007.

Only 4 Ps met principal diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) perhaps because our recruitment materials stated “anxiety disorders” but not “trauma”, therefore attracting fewer PTSD Ps. Of these, 1 did not begin treatment, 1 dropped treatment, and 2 completed treatment. Due to the very small n for this disorder (3 total PTSD Ps who began treatment, only 1 in ACT), these participants were excluded from analyses.

In order to match eligibility requirements between non-study psychotropic medication and non-study psychotherapy, we required a six month stabilization for each type of non-study treatment.

See author MGC for a copy of the CBT treatment manual; the ACT manual is published (Eifert & Forsyth, 2005).

Prior to study training, therapists had received only one or two lectures on CBT and one lecture incorporating thirdwave behavioral therapies at the point of initial study involvement.

Given the mixed anxiety disorder sample and subsequently low n per disorder, ICCs for individual disorders should be interpreted cautiously. Note, however, that agreement was based on all 22 rated audiotapes, not just the audiotapes of Ps with clinically significant symptoms.

This test was selected because the second interviewers included several different trained assessors who rated several tapes each.

We used the original ASI because the revised ASI-3 (Taylor et al., 2007) was not yet published at study initiation.

We did not report 95% confidence intervals for our Feingold (2009) effect sizes because there is not yet a method for doing so (see Feingold, 2009; Odgaard & Fowler, 2010).

To comply with IRB requirements, the original ADISs were already shred for the remaining half of the sample by the point at which we extracted these data. There is no reason to believe, however, that the remaining half differed from the first half in use of non-study psychotherapy.

Due to administrative error in which it was not understood that the treatment credibility measure should be administered to both the CBT and ACT Ps.

Due to the fact that study selection criteria required a CSR of 4 or above, the pre-treatment CSR range was restricted. Thus, the pre-treatment SD, which serves as the denominator in the Feingold (2009) effect size formula, was less than half the SD of the 12m FU CSRs in magnitude (whereas 12m FU SDs on other outcome measures were ≤ their SDs at pre-treatment). If we use the SD at 12m FU to compute effect size for 12m FU group differences on CSR, d = .44.

Contributor Information

Joanna Arch, University of Colorado Boulder

Georg H. Eifert, Chapman University

Carolyn Davies, University of California Los Angeles.

Jennifer C. Plumb Vilardaga, University of Nevada Reno

Raphael D. Rose, University of California Los Angeles

Michelle G. Craske, University of California Los Angeles

References

- Addis AE, Hatgis C, Bourne L, Krasnow AD, Jacob K, Mansfield A. Effectiveness of Cognitive–Behavioral Treatment for Panic Disorder Versus Treatment as Usual in a Managed Care Setting. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(4):625–635. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch JJ, Craske MG. Acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: Different treatments, similar mechanisms? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008;15(4):263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2nd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Cerny JA. Psychological treatment of panic. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, Woods SW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(19):2529–2536. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Emery G, Greenberg RL. Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York: Basic Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Bunce D. Mediators of change in emotion-focused and problem-focused worksite stress management interventions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5(1):156–163. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Bunce D. The role of acceptance and job control in mental health, job satisfaction, and work performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88:1057–1067. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KC, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, Zettle RD. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionniare - II: A revised measure of psychological flexibility and experiential avoidance. epub ahead of print. Behavior Therapy. 2011:1–38. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Abel JL, Newman H. Effects of psychotherapy on comorbid conditions in generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(3):479–483. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1972;3(4):257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR. Theoretical foundations of cognitive-behavioral therayp for anxiety and depression. Annual Review of Psychology. 1996;47:33–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Antony MM, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire in a clinical anxiety disorders sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1992;30(1):33–37. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90093-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. Long-term outcome in cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder: Clinical predictors and alternative strategies for assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(5):754–765. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, DiNardo PA, Barlow DH. Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV. Albany, NY: Center for Stress and Anxiety Disorders; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau, U. S. C. Statiscal Abstract of the United States: 2012. Table 10. Resident Population by Race, Hispanic Origin, and Age: 2000–2009. 2012 from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0010.pdf.

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter MM, Sbrocco T, Gore KL, Marin NW, Lewis EL. Cognitive–Behavioral Group Therapy Versus a Wait-List Control in the Treatment of African American Women With Panic Disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27(5):505–518. [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(1):7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG. Origins of phobias and anxiety disorders: Why more women than men? Oxford, UK: Elsevier Ltd; 2003. [Google Scholar]