Abstract

Background & Aims

We developed a comprehensive self-management (CSM) program that combines cognitive behavioral therapy with relaxation and dietary strategies; 9 sessions (1 hr each) over 13 weeks were shown to reduce gastrointestinal symptoms and increase quality of life in a randomized trial of patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), compared to usual care. The aims of this study were to describe strategies IBS patients selected and continued to use, 12 months after the CSM program began.

Methods

We performed a cohort study to continue to follow 81 adults with IBS (87% female; mean age 45±15 years old) who received the CSM program in the previous clinical trial. During the last CSM session, participants selected strategies they intended to continue using to manage their IBS. CSM strategies were categorized into subthemes of diet (composition, trigger foods, meal size or timing, and eating behaviors), relaxation (specific relaxation strategies and lifestyle behaviors), and alternative thoughts (identifying thought distortions, challenging underlying beliefs, and other strategies). Twelve months later, participants were asked how often they used each strategy (not at all or rarely, occasionally, often, very often, or almost always).

Results

At the last CSM session, 95% of the patients selected the subthemes of specific relaxation strategies, 90% selected diet composition, and 90% identified thought distortions (90%) for continued use. At 12 months, 94% of the participants (76/81) were still using at least 6 strategies, and adherence was greater than 79% for all subthemes.

Conclusions

We developed a CSM program to reduce symptoms and increase quality of life in patients with IBS that produced sustainable behavioral changes in almost all patients (94%) after 1 year of follow up.

Keywords: alternative medicine, self-management, behavioral therapy, psychology

Introduction

There is increasing evidence that psychological treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy, relaxation therapies, and dietary management are effective strategies for the management of patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).1 Our team therefore combined these strategies to develop a 9-week comprehensive self-management program (CSM) for IBS patients.2 In a prior study by our team, 188 adult IBS patients randomized to our CSM program demonstrated greater improvements in daily diary gastrointestinal (GI) symptom scores and quality of life (QOL) (p < 0.001) compared to usual care for at least 12 months.2 This follow-up study will now explore patients' perspectives on which strategies were considered the most effective for IBS symptom management and the adherence to each strategy at 12 months.

Understanding which non-medication therapies IBS patients prefer could help determine which strategies to emphasize during CSM teachings, leading to improved patient adherence and more appropriate use of medical resources.3 There are few studies describing patient's attitudes on and preferences of IBS non-medication treatments. In a telephone questionnaire study, Heitkemper et al asked 1014 women with IBS about the use of six common non-medication treatments. Diet (67%), relaxation exercises (38%) and stress reduction techniques (33%) were more commonly tried than psychotherapy (13%) and biofeedback (6%).4 In a questionnaire study by Harris et al, 645 IBS patients evaluated their acceptability of the following treatments: tablets, diet change, yoga, stomach cream, homeopathy, heat pad, hypnotherapy, acupuncture, and suppositories. The most acceptable treatments were diet (82%) and yoga (77%).5 We hypothesized that our participants would also preferentially select dietary and relaxation over alternative thinking strategies.

Self-reported adherence rates in the study by Heitkemper et al were 47% when IBS patients were asked if they followed their physician's IBS treatment recommendations “most of the time”.4 Adherence rates for behavioral interventions for other chronic medical conditions varied between 11% and 21%.6-8 Given that our participants can select which CSM strategies to continue, we hypothesized that adherence rates for this study would be greater than 50%.

The aims of this study was to describe which CSM strategies participants preferred immediately following the CSM program and adhered to at 12 months. We also assessed whether the ongoing use of specific CSM strategies at 12 months was associated with greater improvements in GI symptom scores. Finally, we evaluated whether patients' CSM strategy selections at the last session and at 12 months were related to any underlying demographic or clinical characteristics. Findings from this study will provide clinicians insight on CSM strategies patients with IBS find helpful and are able to adhere to.

Methods

This is a cohort study using follow-up data from a randomized trial of in-person or telephone CSM intervention versus usual care for adults with IBS (previously described elsewhere).2 Eighty percent (101 of the 126 participants) randomized to receive CSM intervention completed a comprehensive plan at their final CSM session and were included in this present analysis. Eighty-one participants (80%) provided 12-month follow-up data. Human participants institutional review approval was obtained prior to enrolling participants (May 2002). This study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov through the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Comprehensive Self-Management Sessions

The program was delivered in nine one-hour sessions within a 13-week period by two trained psychiatric nurse therapists. CSM sessions covered three main themes: “diet,” “relaxation” and “alternative thoughts.” Supplemental Table 1 provides an overview of the educational material covered during each CSM session and its corresponding homework assignments.

Specific strategies within each main theme were selected for each participant based on individualized assessments by the nurse therapist. For “diet,” participants completed a Food Frequency Questionnaire and food diary.9 A registered dietitian reviewed these items to identify specific problems in a participant's diet for tailored strategies. For “alternative thoughts,” participants completed a worksheet to help identify problematic thoughts following a specific event. To mitigate therapist bias, the provided workbook was written by two nurse therapists. All sessions were also recorded and reviewed by a separate nurse therapist to provide feedback if an inappropriate emphasis was spent on specific CSM strategies.

Comprehensive Plan

As the final homework assignment, participants were asked to write a comprehensive plan that specified which strategies they found the most helpful and planned on using over the next year in managing their IBS symptoms. The strategies included by each participant were categorized by P.B. into one of the strategies introduced from the CSM program. J.Z., a gastroenterologist, confirmed this categorization. Any disagreements on categorizations were resolved by a discussion between P.B. and J.Z. Table 1 outlines the CSM strategies within each main and sub theme.

Table 1. Comprehensive Self-Management Strategy Preferences at Last Session and Uses and Adherences at 12-months Post-Randomization.

| CSM Themes/Subthemes with Corresponding Strategies | Preferences at Last Session | Complete Case Analysis* | Conservative Imputation of Missing Data** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSM Use at 12 months$ | CSM Adherences at 12 months$ | CSM Use at 12 months$ | CSM Adherences at 12 months$ | ||

| All Subjects (N = 101) | All Subjects with 12-month data (N = 81) | Subjects who Selected Strategy in CP (N = variable) | All Subjects (N = 101) | Subjects who Selected Strategy in CP (N = variable) | |

| DIET | |||||

| Diet composition | 90% | 90% | 99% | 72% | 80% |

| Alter fiber to tolerable amount | 64% | 51% | 82% | 41% | 63% |

| Increase fluids to goal amount | 54% | 53% | 92% | 43% | 78% |

| Eat a balanced diet | 48% | 44% | 92% | 36% | 75% |

| Supplements & vitamins | 32% | 30% | 89% | 24% | 75% |

| Trigger foods | 81% | 75% | 91% | 60% | 74% |

| Meal size/timing | 75% | 69% | 92% | 55% | 74% |

| Eat small, frequent meals | 70% | 63% | 89% | 51% | 72% |

| Eat breakfast | 15% | 15% | 100% | 12% | 80% |

| Eating behaviors | 43% | 41% | 89% | 33% | 77% |

| Meal planning | 34% | 28% | 79% | 23% | 68% |

| Eat more slowly | 11% | 11% | 100% | 9% | 82% |

| Eat in relaxed setting | 5% | 5% | 80% | 4% | 80% |

| RELAXATION | |||||

| Specific relaxation strategies | 95% | 75% | 79% | 60% | 64% |

| Quieting response | 66% | 46% | 67% | 37% | 55% |

| Abdominal breathing | 59% | 47% | 76% | 38% | 63% |

| Visualization | 28% | 9% | 37% | 7% | 25% |

| Active progressive muscle relaxation | 20% | 5% | 25% | 4% | 20% |

| Autogenics | 16% | 9% | 54% | 7% | 44% |

| Mini-relaxation exercises | 15% | 10% | 53% | 8% | 53% |

| Own version or combination of relaxation exercises | 11% | 4% | 30% | 3% | 27% |

| Body scan | 9% | 7% | 86% | 6% | 67% |

| Passive progressive muscle relaxation | 8% | 5% | 67% | 4% | 50% |

| Lifestyle behaviors | 86% | 84% | 99% | 67% | 78% |

| Exercise | 57% | 48% | 85% | 39% | 67% |

| Time for self | 56% | 53% | 92% | 43% | 75% |

| Good sleeping habits | 23% | 22% | 82% | 18% | 78% |

| Spiritual practices | 23% | 14% | 69% | 11% | 48% |

| Relaxation strategies during times of stress | 7% | 2% | 67% | 2% | 29% |

| ALTERNATIVE THOUGHTS | |||||

| Identify thought distortions | 90% | 83% | 89% | 66% | 74% |

| Should think | 39% | 37% | 91% | 30% | 77% |

| Overgeneralization of negative | 37% | 35% | 85% | 28% | 76% |

| All or nothing thinking | 17% | 16% | 93% | 13% | 76% |

| Discounting the positive | 8% | 6% | 71% | 5% | 63% |

| Labeling | 7% | 6% | 100% | 5% | 71% |

| Personalization and blame | 5% | 5% | 80% | 4% | 80% |

| Catastrophic thinking | 5% | 2% | 100% | 2% | 40% |

| Emotional reasoning | 4% | 5% | 100% | 4% | 100% |

| Challenge underlying beliefs | 55% | 43% | 80% | 35% | 63% |

| Perfectionism | 23% | 19% | 88% | 15% | 65% |

| Control | 17% | 12% | 77% | 10% | 59% |

| Self-esteem | 16% | 10% | 73% | 8% | 50% |

| IBS | 12% | 11% | 90% | 9% | 75% |

| Assertiveness | 7% | 6% | 71% | 5% | 71% |

| Other useful strategies | 51% | 48% | 89% | 39% | 76% |

| 6-step problem solving process | 19% | 19% | 88% | 15% | 79% |

| Find support/connection | 14% | 12% | 77% | 10% | 71% |

| Action plan | 13% | 11% | 90% | 9% | 69% |

| Distraction/Refocus | 9% | 6% | 62% | 5% | 56% |

| Anticipate and recognize stress | 7% | 9% | 100% | 7% | 100% |

| Avoid rumination/worry | 7% | 7% | 100% | 6% | 86% |

CSM = comprehensive self-management; CP = comprehensive plan

Participants with no follow-up data at 12-month post-randomization were excluded.

Participants with no follow-up data at 12-month post-randomization were assumed to be non-adherent.

CSM preference and adherence percentages based on participants' report of at least “often” use (≥ 2 days a week) of each respective CSM strategy.

Use of CSM Strategies at 12 Months

At 12 months while participants were being re-assessed for the parent study's outcome measures, the nurse therapist would contact participants and assess whether they were still using each of the CSM strategies in their comprehensive plan by asking: “How often do you use this strategy?” Participants answered using one of the following responses: not at all/rarely, occasionally (at least 1 day a week), often (at least 2 days a week), very often (at least 4 days a week) or almost always.

Statistical Analysis

There was no significant difference in the strategies selected to be part of the comprehensive plan between participants randomized to receive CSM in-person or by telephone (data not shown). The data from the two intervention arms in the parent study were therefore combined for this study. Chi-square tests and t-tests were used to test whether those who provided strategy use data at 12 months differed from those who did not.

CSM strategy preferences at the last treatment session were described as the percentage of participants selecting each CSM strategy in their comprehensive plan amongst all participants who provided such a plan (N = 101). At 12 months, CSM strategy use and adherences were described as the percentage of participants still “using” each CSM strategy amongst all participants and amongst all participants who selected it for their comprehensive plan respectively. Participants were considered “using” a CSM strategy if they reported at least often use. We calculated these percentages using two different approaches: a complete case analysis and a conservative imputation of missing data. The complete case analysis only included participants with 12-month data (N = 81). The conservative imputation of missing data approach included all participants who completed a comprehensive plan (N = 101) and assumed participants with no follow-up data to be non-adherent to any CSM strategy.

To evaluate whether the use of some individual CSM strategies at 12 months might be associated with GI symptom scores, participants were divided into tertiles based on the amount of their improvement: least, mid and most. Chi-square tests were used to test whether the use of each CSM strategy or subtheme differed by tertile of improvement.

Chi-squared tests were performed to determine whether CSM subtheme strategy selections were related to demographic and clinical characteristics at the last CSM session and at 12 months. Demographic characteristics were dichotomized as follows: age (≤ 45 years vs. > 45 years based on the median age), gender (male vs. female), marital status (married/partnered vs. single), ethnicity (White vs. non-White), education (below vs. equivalent/beyond college degree) and family income (< $65,000 vs. ≥ $65,000). Clinical characteristics included IBS predominant bowel patterns (diarrhea, constipation, or mixed). Statistical significance was considered if p < 0.01. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 19.

Results

Participant Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Participants were mainly female (87%) and White (86%). The average age was 45 (SD = 15) years old. About half of the participants were either married/partnered (49%), held at least a college degree (74%), reported a family income over $65,000 per year (52%) and classified their jobs as professional (43%). Half (50%) were classified as the diarrhea-predominant IBS; the other half was divided into the constipation-predominant (28%) and mixed (23%) subtypes.

The only significant demographic difference observed between participants who did or did not provide follow-up data at 12 months was age (mean [SD], 47 [14] versus 39 [12], p = 0.002). There was also a trend towards lower baseline “percentage of days with moderate to very severe GI symptoms” for participants who provided follow-up data compared to those who did not (mean [SD], 47% [14%] versus 39 [12%], p = 0.07).

Selected CSM Strategies and Adherence Rates

The average number of CSM strategies identified per participant during their comprehensive plan was 10 (SD = 3). Participants identified more CSM strategies in the “diet” (5, SD = 2) than “relaxation” (3, SD = 1) and “alternative thoughts” (2, SD = 1) main themes.

Table 1 shows the CSM strategy preferences of participants at the last session. It also shows the CSM strategy uses and adherences of participants at 12 months using both the complete case and conservative analyses described in the Methods.

The CSM subthemes most frequently selected in the comprehensive plan were “specific relaxation strategies” (95%), “diet composition” (90%) and “identify thought distortions” (90%). The individual CSM strategies most frequently selected in the comprehensive plan were: “eat small, frequent meals” (70%), the “quieting response” (66%) and “alter fiber to tolerable amount” (64%). For certain CSM strategies (i.e. trigger foods, vitamins/supplements, exercise, time for self), participants wrote down specific examples (Supplemental Table 2).

Based on the complete case analysis, the CSM subthemes most frequently being used were “diet composition” (90%), “lifestyle behaviors” (84%), and “identify thought distortions” (90%). “Specific relaxation strategies” were still being used by participants at 12 months (75%) but its use declined compared to its intended use (95%). The individual CSM strategies most frequently being used at 12 months were “eat small, frequent meals” (63%), “time for self” (53%), “increase fluids to goal amount” (53%) and “alter fiber to tolerable amount” (51%).

Adherence for all chosen CSM subthemes was ≥ 79%. At 12 months, 94% of responding participants were still using at least six CSM strategies (range, 3-20; n=81). The highest adherence was observed for “diet composition” (99%) and “lifestyle behaviors” (99%). These results are from the complete case analyses. The conservative analysis gave smaller estimates. It is likely that the correct estimates are somewhere in between the complete case and conservative results.

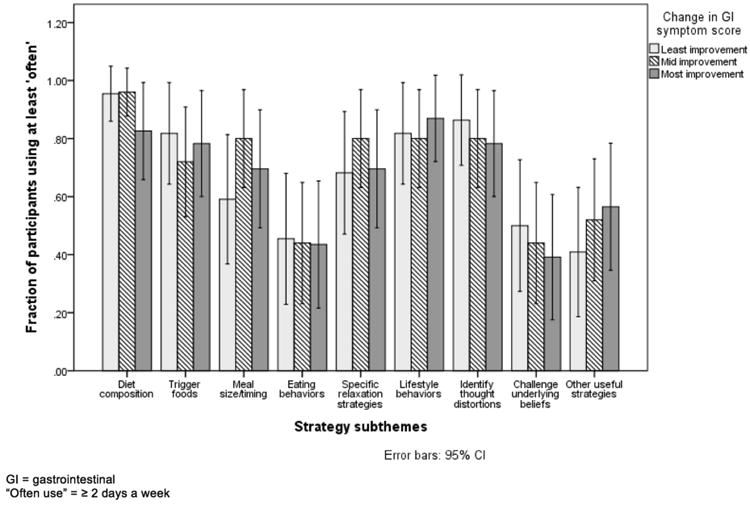

There were no significant associations between the “often” use of CSM strategies and change in GI symptom scores divided into tertiles (least, mid and most improved) at 12 months (Figure 1). Women were more likely to identify “specific relaxation strategies” in their comprehensive plan and at 12 months compared to men (p = 0.01). All other demographic and clinical characteristics were not significantly related to specific CSM strategy selections.

Figure 1. Association between the “often” use of comprehensive self-management strategies at 12 months and change in gastrointestinal symptom scores divided into tertiles (least, mid and most improved).

Discussion

Completion of our CSM program resulted in sustainable behavioral changes. At 12 months, the majority of participants were still using CSM strategies. This high level of adherence exceeded our expectations and prior observed adherence rates to behavioral changes in other patient populations.6-8 The primary goal of our CSM program was to provide IBS patients with a set of effective strategies to choose from with the expectation of ongoing use of only the most effective and feasible strategies for each individual patient. Based on the results of this study, this goal was successfully met.

The high adherence rates reported in this study were likely attributable to the unique structure of our CSM program which offered flexibility, individualization, practice and personal feedback. Our CSM program gave participants the freedom to pick and choose which strategies to use. There is growing evidence to support such patient preference and participation for IBS symptom management.10, 11 By trial and error, participants could assess, along with the guidance of the nurse therapist, which strategies best impacted their personal IBS symptoms and integrated into their daily routines. The variety of choices made by participants in this study supports the concept that different strategies work for different people. It was therefore not surprising to find a lack of association between the use of any specific CSM strategy and GI symptom scores.

Personal contact with the nurse therapist might have also contributed to the high adherence rates. IBS patients were provided reassurance that they were correctly performing CSM strategies by observed practice and real-time feedback. Participants also received scheduled calls by our nurse therapist at 6 and 12-months. Such a call might have offered encouragement and support to the participant, resulting in increased adherence to behavioral changes as seen in other patient populations.6 This effect might have been even more pronounced in this study since participants had established relationships with these therapists.

These high adherence rates possibly contributed to the lasting improvements seen in both symptoms and QOL in the parent study. In the parent study, 40% of participants had at least a 50% improvement in their GI symptom scores at 12 months.2 Further analysis showed that 84% of participants demonstrated at least some improvement in GI symptom scores. Although our study's adherence rates (≥99%) exceeded the percentage of participants demonstrating any GI symptom improvement (84%), this could be explained by CSM strategy adherence for therapeutic benefits outside of IBS symptom management or inflated adherence rates. Anecdotally, some of our participants with no symptom improvement described other factors (e.g. stress) accounting for their worsening IBS symptom scores despite perceived efficacy of CSM strategies.

Despite its effectiveness though, our CSM program is not realistically accessible to all IBS patients. It is our hope that the results of this study can guide clinicians on which CSM strategies to strategically focus their efforts on first, especially given their limited time and resources. Not all CSM strategies are created equally in their effectiveness and feasibility. For example, “trigger foods” was one of the most preferred and durable strategies selected by our participants. Providers might therefore consider trigger food elimination as their initial approach for IBS symptom management. Instead of familiarizing themselves with every CSM strategy, providers could start by finding patient educational materials on and/or local expert nutritionists in elimination diets. Alternatively, since our CSM program has been converted into a book, they could first focus on its chapters highlighting diet.12

As in past studies, dietary and relaxation strategies were favored over alternative thinking ones.4, 5, 13 Many factors are likely contributing to this pattern. First, psychological therapies are generally perceived by IBS patients with a non-specific dislike, fixed preconceptions and skepticism.5 Second, identifying an individual's thought distortions and underlying beliefs is difficult and takes time. Third, altering one's thinking, especially with only nine CSM sessions, is extremely challenging.

Women in our study were more likely than the men to identify strategies from the “specific relaxation strategies” subtheme. This was supported by a systematic review which found women to be more accepting of complementary alternative medicine but contradicts prior studies where gender had no association with IBS treatment preferences.5, 14, 15 The lack of association of income, age and other personal characteristics with CSM strategy selection observed in this study might be due to the growing acceptance and popularization of alternative medicine.15, 16

Study Limitations

Our study results might not be applicable to all populations. Participants were mainly young, well-educated, and married White females who suffered from diarrhea-predominant IBS. This population differed from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis that demonstrated only a slight increased prevalence of IBS in women and a more predominant constipation stool pattern in women compared to men.17 This study might have also oversimplified some personal characteristics (such as White versus non-White) and be unable to highlight potential differences between CSM strategy selections based on these characteristics.

Second, we did not evaluate the psychometric properties of our study's main outcome measure: CSM strategy adherence. Therefore, the adherence rates reported in this study were possibly inflated. This study relied on self-reported adherence, which has been shown to be markedly overestimated in other patient populations.6-8 Participants were also considered adherent to strategies they might have been using regularly prior to the study despite no behavioral changes. Responding participants might have also wanted to give socially desirable responses, namely ongoing adherence to CSM strategies. Regardless of whether the adherence rate was falsely elevated though, the parent study still demonstrated a significant improvement in both GI symptoms and QOL.

Third, participants might have been influenced to select certain CSM strategies based on the teaching time spent on them. “Abdominal breathing” and the “quieting response,” both preferred CSM strategies, were given regularly as homework assignments. CSM dietary strategies, also popular amongst participants, were taught in approximately 50% of CSM sessions. More teaching time is not always equivalent however to more emphasis. Some strategies take more time to explain and require more practice to master. For example, it takes more time to learn how to identify trigger food groups using food labels than how to walk three times a week.

Although the magnitude is debatable, a “therapist effect” could have generated biased CSM strategy selections and adherence.18 Therapists might value one treatment above another and communicate this bias to their patients and/or might be more skilled in teaching one treatment over another. Prior studies have noted the influence of treatment acceptability by IBS patients when it is recommended by a provider.5, 19 To mitigate this bias, all sessions were recorded and reviewed by a separate nurse therapist to provide feedback to the delivering therapist if an inappropriate emphasis was spent on specific CSM strategies. These measures did not however address another potential bias: the nurse therapists who taught the CSM program were also the same ones collecting follow-up data.

Finally, the rationale behind participants' selection and continuation of CSM strategies was not explored. Convenience, familiarity, preference, access, time commitment, physical capabilities and/or perceived effectiveness were all possible contributing factors in such decisions. Certain CSM strategies might have even been continued for non-IBS health benefits. Familiarity might have been the reason for the high adherence rates seen for “diet composition” and “lifestyle behaviors.” These strategies are not IBS specific and require little to no additional training.

Such information could help improve our CSM program. If a CSM strategy was effective but certain logistics (e.g. time, money, location) prevented participants from using it, we could spend more time identifying solutions for integrating it into patients' routines. If a CSM strategy felt intimidating or confusing, we could dedicate more session time and/or assign more homework assignments on it. If a CSM strategy was not effective in reducing IBS symptoms, we could completely omit it from our program.

Conclusion

Our CSM program resulted in sustainable behavioral changes for IBS symptom management in the majority of our participants, possibly accounting for the long-lasting improvements seen in both GI symptoms and QOL. A multi-component CSM intervention allowed patients to select the most effective and feasible strategies for their individualized set of symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. Overview of Comprehensive Self-Management Sessions

Supplemental Table 2. Detailed Responses of Relevant CSM Strategies

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Supported by grants from the NINR, NIH (R01 NR004142 and P30 NR04001).

Abbreviations

- CSM

comprehensive self-management

- FODMAP

fermentable, oligo-, di-, monosaccharides and polyols

- GI

gastrointestinal

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- QOL

quality of life

Footnotes

Author contributions: conception and design PB, MJ, KC; acquisition of data PB, MJ, KC; analysis and interpretation of data JZ, KC, PB; drafting of the manuscript JZ; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content MH, KC, PB, MJ; statistical analysis KC; obtaining funding MH; administrative, technical, material support JZ, MH; supervision MH.

Disclosures: None

Writing Assistance: No other authors

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lackner JM, Mesmer C, Morley S, et al. Psychological Treatments for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1100–1113. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarrett ME, Cain KC, Burr RL, et al. Comprehensive self-management for irritable bowel syndrome: randomized trial of in-person vs. combined in-person and telephone sessions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3004–14. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halpert A, Godena E. Irritable bowel syndrome patients' perspectives on their relationships with healthcare providers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:823–30. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.574729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heitkemper M, Carter E, Ameen V, et al. Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Differences in Patients' and Physicians' Perceptions. Gastroenterology Nursing. 2002;25:192–200. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris LR, Roberts L. Treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: patients' attitudes and acceptability. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:65. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simek EM, McPhate L, Haines TP. Adherence to and efficacy of home exercise programs to prevent falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of exercise program characteristics. Prev Med. 2012;55:262–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung ML, Lennie TA, de Jong M, et al. Patients differ in their ability to self-monitor adherence to a low-sodium diet versus medication. J Card Fail. 2008;14:114–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang PS, Benner JS, Glynn RJ, et al. How well do patients report noncompliance with antihypertensive medications?: a comparison of self-report versus filled prescriptions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13:11–9. doi: 10.1002/pds.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristal ARF, F Z, Coates RJ, Oberman A, George V. Associations of Race/Ethnicity, Education, and Dietary Intervention with Validity and Reliability of a Food Frequency Questionnaire. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;146:856–869. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drossman DA, Morris CB, Schneck S, et al. International survey of patients with IBS: symptom features and their severity, health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:541–50. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318189a7f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Protheroe J, Rogers A, Kennedy AP, et al. Promoting patient engagement with self-management support information: a qualitative meta-synthesis of processes influencing uptake. Implement Sci. 2008;3:44. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barney P, Weisman P, Jarrett M, et al. Master Your IBS: An 8-Week Plan to Control the Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Bethesda, MD: AGA Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lacy BE, Weiser K, Noddin L, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: patients' attitudes, concerns and level of knowledge. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1329–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Huskic SS, et al. Predictors of conventional and alternative health care seeking for irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:841–851. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ernst E. Prevalence of use of complementary/alternative medicine: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78:252–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong SC, Hurlstone DP, Pocock CY, et al. The Incidence of Self-prescribed Oral Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use by Patients With Gastrointestinal Diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:138–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lovell RM, Ford AC. Effect of gender on prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:991–1000. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falkenstrom F, Markowitz JC, Jonker H, et al. Can psychotherapists function as their own controls? Meta-analysis of the crossed therapist design in comparative psychotherapy trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:482–91. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jamieson AE, Fletcher PC, Schneider MA. Seeking Control Through the Determination of Diet: A Qualitative Investigation of Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clinical Nurse Specialist. 2007;21:152, 160. doi: 10.1097/01.NUR.0000270015.97457.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1. Overview of Comprehensive Self-Management Sessions

Supplemental Table 2. Detailed Responses of Relevant CSM Strategies