Abstract

Men who have sex with men (MSM) living in countries with strong stigma toward MSM are vulnerable to HIV and experience significant barriers to HIV care. Research is needed to inform interventions to reduce stigma toward MSM in these countries, particularly among healthcare providers. A cross-sectional survey of 1158 medical and dental students was conducted at seven Malaysian universities in 2012. Multivariate analyses of variance suggest that students who had interpersonal contact with MSM were less prejudiced toward and had lower intentions to discriminate against MSM. Path analyses with bootstrapping suggest stereotypes and fear mediate associations between contact with prejudice and discrimination. Intervention strategies to reduce MSM stigma among healthcare providers in Malaysia and other countries with strong stigma toward MSM may include facilitating opportunities for direct, in-person or indirect, media-based prosocial contact between medical and dental students with MSM.

Keywords: Contact hypothesis, Discrimination, HIV, Malaysia, MSM, Stigma

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) bear the greatest burden of the HIV epidemic worldwide, with MSM experiencing greater prevalence of HIV than adults in general in every global context [1, 2]. Moreover, HIV transmission continues to expand among MSM despite decreasing among most other adult populations [1, 2]. Beyrer and colleagues have described these high rates of HIV prevalence and incidence among MSM as the “next wave of global HIV” [2], and have called for significant changes in healthcare delivery to enhance HIV treatment and prevention strategies for MSM [3].

Structural MSM Stigma

Stigma has been cited as a critical barrier to HIV treatment and prevention services for MSM [3, 4]. Societal stigma is social devaluation and discrediting associated with a characteristic, mark, or identity [5]. Societal stigma of MSM is structurally manifested and reinforced by civil laws in some countries. Although several countries have recently eradicated laws restricting rights of MSM, others have stood by or even passed new persecutory legislation [6]. As of May 2014, same-sex sexual acts were punishable by death in five countries and by imprisonment in 78 countries [7].

These persecutory laws make it dangerous for MSM to access HIV treatment and prevention services [6, 8]. In Senegal, MSM reported heightened fear for their safety and hiding following the arrest of HIV prevention workers under a law restricting “unnatural” acts with persons of the same sex [9]. HIV service provision and uptake declined as both MSM and providers feared arrest. In Asia, MSM living in countries scoring lower on the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Human Rights Index (which includes persecutory laws for same-sex sexual acts as an indicator of the index) report less exposure to HIV prevention services, less HIV knowledge and testing, and more unprotected anal intercourse [10]. MSM living in countries with laws persecuting same-sex sexual acts appear to be particularly vulnerable to both becoming infected with HIV and experiencing greater barriers to care once infected [4].

Potential for MSM Stigma Reduction Among Healthcare Providers

It is critical to improve HIV treatment and prevention for MSM, particularly in these countries with strong societal MSM stigma. In addition to its manifestations at the structural level, societal stigma is manifested at the individual level among healthcare providers as prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination [11]. Prejudice is a negative orientation toward MSM. Stereotypes are group-based beliefs, or cognitions, about MSM that are applied to individual MSM, such as MSM are promiscuous. Discrimination is unfair or unjust treatment, such as providing MSM with care worse than provided to other patients.

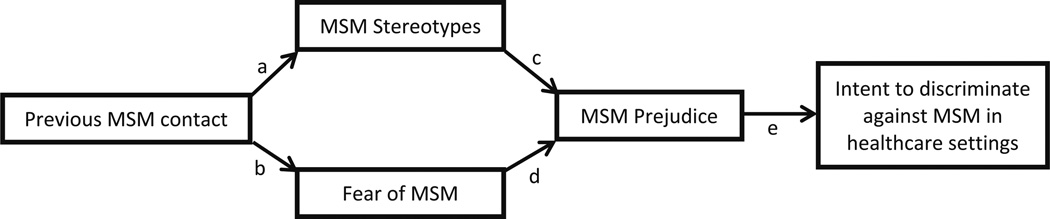

Decades of research on the contact hypothesis [12] demonstrates that prejudice toward outgroups, or social groups with which individuals do not identify [13], may be reduced via interpersonal interaction [14]. Meta-analytic evidence suggests that interpersonal contact leads to greater knowledge about outgroup members, which may reduce stereotypes about outgroups [15]. Evidence further suggests that contact leads to less anxiety or fear of interacting with outgroup members. Reductions in stereotypes and fear, in turn, are associated with reduced prejudice. Prejudice is a key motivator of discrimination [16]; therefore, reduced prejudice can lead to reduced discrimination. This process, as applied to MSM, is depicted as a conceptual model in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of effect of previous contact with MSM on discrimination intentions among healthcare providers

Current Study

In the current study, we evaluate this conceptual model among medical and dental students in Malaysia. The prevalence of HIV in Malaysia is estimated to be 0.4 %, with approximately 86,000 Malaysians living with HIV [17]. HIV has historically been concentrated among people who inject drugs, but is rapidly increasing among MSM [17, 18]. HIV risk behaviors are prevalent and HIV testing rates are low among Malaysian MSM [19].

Same-sex sexual acts are forbidden legally and culturally in Malaysia. They are punishable under Malaysian Penal Code Section 377 and Sharia law. Section 377 is a remnant of a British colonial-era law [20] and punishes “carnal intercourse against the order of nature,” defined as anal or oral penile penetration, and states that “whoever voluntarily commits carnal intercourse against the order of nature shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to 20 years, and shall also be liable to whipping” [7]. Islamic Sharia law criminalizes anal sex (“liwat”) among Muslims and carries punishments including imprisonment, fines, and whipping. Malaysian religious authorities regularly raid MSM venues such as bars, saunas, parks, and cruising spots to enforce Sharia law. Top Malaysian officials, including former and current prime ministers, have publicly condemned MSM [21]. The imprisonment of an opposition leader who allegedly committed a crime under Section 377 received global attention in the 1990s and 2000s [20, 22]. Other MSM, and men perceived to be MSM, persecuted under Section 377 describe physical and psychological abuse during incarceration [20]. Malaysia scored in the bottom three of 22 Asian countries on the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Human Rights Index, reflecting significant repression endured by Malaysian sexual minorities [10].

We aim to examine differences between students who report previous versus no previous interpersonal contact with MSM, including differences in socio-demographic and clinical characteristics as well as endorsement of MSM stereotypes, fear, prejudice, and discrimination intent. Additionally, we aim to explore the process linking previous interpersonal contact with MSM with lower prejudice and discrimination intent.

Methods

Procedure and Participants

A cross-sectional survey of undergraduate-level medical and dental students pursuing a Bachelor of Medicine Bachelor of Surgery or a Bachelor of Dental Surgery (MBBS) degree was conducted between May and October 2012 at seven public and private Malaysian universities. Participating universities included: University of Malaya, National University of Malaysia, International Islamic University Malaysia, University Malaysia Sarawak, Penang International Dental College, Universiti Teknologi MARA Malaysia, and Universiti Sains Malaysia. A link to the survey was emailed to students from university administrative offices. Students were informed that their participation was voluntary, and that their answers would remain anonymous and would not affect their student status. The survey lasted 30 minutes or less. Institutional review boards at Yale University and all participating Malaysian universities approved the study.

Of 3191 students who were emailed the link, 1296 accessed the link (40.6 % of students emailed), and 1165 responded (89.9 % of students who accessed the link). Our data analyses are limited to 1158 students who provided information regarding whether they had previous contact with MSM.

Measures

All measures were reviewed and judged culturally appropriate by Malaysian representatives of the research team. Education and training occur in English at all participating universities; therefore, the survey was conducted in English.

Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Participants reported their age, gender, ethnicity, religion, year of study, training status (pre-clinical, clinical), and area of study (dental, medicine).

Previous MSM Contact

Participants indicated yes or no to whether they have had contact with MSM in response to the question “Do you personally know any homosexuals?”

Stereotypes

A four-item measure of stereotypes was developed for the current study. Participants indicated their agreement to items on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree [1] to strongly agree [5]. Items included: “Men who have sex with men are promiscuous,” “Men who have sex with men do not care about their health,” “Men who have sex with men make bad decisions,” and “Men who have sex with men are untrustworthy.” A mean stereotypes score was created, which demonstrated high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.88).

Fear, Prejudice, Discrimination Intent

Measures of fear, prejudice, and discrimination intent were adapted from subscales of the multidimensional HIV stigma scale developed by Stein and Li [23]. This scale was originally developed to measure attitudes about people living with HIV/AIDS as well as perceptions of appropriate medical care for and responsibilities toward patients with HIV among healthcare professionals in China. The research team adapted items to refer to MSM in Malaysia. Participants indicated their agreement to all items on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree [1] to strongly agree [5].

Three fear items included: “I am afraid of men who have sex with men,” “I am afraid that men who have sex with men will be attracted to me,” and “I am afraid that men who have sex with men will give me HIV/AIDS if I treat them.” A mean fear score was created, which demonstrated reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.78). Four prejudice items included: “Men who have sex with men do not belong in society,” “Men who have sex with men should be identified,” “Men who have sex with men should not be able to visit public hospitals,” and “It is unnatural for men to have sex with men.” A mean prejudice score was created, which demonstrated adequate reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.63). Four discrimination intent items included: “I am willing to work with men who have sex with men,” “I am willing to provide the same care to men who have sex with men as I am to other patients,” “I am willing to do physical exams on men who have sex with men,” and “I am willing to interact with men who have sex with men the same way I interact with other patients.” A mean discrimination score was created, which demonstrated strong reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.93).

Data Analysis

First, we explored differences in socio-demographic and clinical characteristics among participants who had versus had not had previous contact with MSM. Second, we conducted a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) in SPSS 22 to examine the association between previous contact with MSM with all stigma-related variables, including stereotypes, fear, prejudice, and discrimination intent. The MANOVA included socio-demographic and clinical characteristics (age, gender, religion, year of study, training status, area of study) to estimate the relationship between previous contact with MSM and stigma-related variables controlling for these characteristics. Third, we conducted a path analysis in mPlus 7.2 to evaluate our hypothesis regarding the psychological process linking previous contact with MSM with lower prejudice and discrimination intentions (Fig. 1). Path analysis is a form of structural equation modeling that is recommended when researchers have hypotheses regarding causal associations between measured variables [24]. The use of path analysis allowed us to include multiple mediators operating in serial, correlate errors between stereotypes and fear to account for their association, and control for the effects of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics on all mediating and outcome variables. We used bootstrapping, a statistical resampling method, to estimate indirect effects of predictor variables on outcome variables via mediating variables (e.g. the effect of previous MSM contact on MSM prejudice via MSM stereotypes). This yielded a fully saturated model, which has zero degrees of freedom and yields no information about model fit.

Results

Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Previous MSM Contact

Socio-demographic characteristics stratified by whether students reported previous contact with MSM are included in Table 1. On average, students were in their early twenties and the majority identified as female, Malay, and Muslim. On average, students were in their third year of study and undergoing clinical training. Slightly more students were studying dentistry than medicine.

Table 1.

Participant socio-demographic and clinical characteristics by contact with MSM, n = 1158

| Overall [M(SD) or n (%)] |

No previous MSM contact [M(SD) or n (%)] |

Previous MSM contact [M(SD) or n (%)] |

Comparison by previous contact [t or χ2] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||

| Sample size | 1158 (100) | 999 (86.3) | 159 (13.7) | |

| Age | 22.43 (1.65) | 22.38 (1.66) | 22.75 (1.57) | t(1147) = −2.65** |

| Gender | χ2(1) = 37.76*** | |||

| Male | 366 (31.6) | 283 (77.3) | 83 (22.7) | |

| Female | 790 (68.2) | 716 (90.6) | 74 (9.4) | |

| Ethnicity | χ2(2) = 7.60* | |||

| Malay | 716 (61.8) | 633 (88.4) | 83 (11.6) | |

| Chinese | 342 (29.5) | 283 (82.7) | 59 (17.3) | |

| Other | 96 (8.3) | 79 (82.3) | 17 (17.7) | |

| Religion | χ2(2) = 8.00* | |||

| Muslim | 741 (64.0) | 654 (88.3) | 87 (11.7) | |

| Buddhist | 257 (22.0) | 209 (81.3) | 48 (18.7) | |

| Other | 160 (13.8) | 136 (85.0) | 24 (15.0) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Year of study | 3.31 (1.42) | 3.26 (1.42) | 3.67 (1.41) | t(1155) = −3.38*** |

| Training status | χ2(1) = 7.45** | |||

| Pre-clinical | 395 (34.1) | 356 (90.1) | 39 (9.9) | |

| Clinical | 758 (65.5) | 639 (84.3) | 119 (15.7) | |

| Area of study | χ2(1) = 4.97* | |||

| Dental | 657 (56.7) | 579 (88.1) | 78 (11.9) | |

| Medical | 492 (42.5) | 411 (83.5) | 81 (16.5) | |

p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001.

Percentages may not total to 100 due to missing data

Only 14 % of students reported previous contact with MSM. Students with previous contact with MSM were slightly older. More males than females reported previous contact with MSM. Chinese students and students of other ethnicities reported more previous contact with MSM than Malay students. Similarly, Buddhist students and students of other religions reported more previous contact with MSM than Muslim students. Students with previous contact with MSM were slightly further along in their training. More clinical than pre-clinical students reported previous contact with MSM, and more medical than dental students reported previous contact with MSM.

Additional exploratory analyses demonstrated considerable overlap between ethnicity and religion. Almost all participants who identified as Malay (n = 716) also identified as Muslim (n = 715/716, 99.9 %). Similarly, most participants who identified as Chinese also identified as Buddhist (n = 255/342, 75.0 %). Given overlap between religion and ethnicity, only religion was included in subsequent multivariate analyses to prevent multicollinearity.

Stereotypes, Fear, Prejudice and Discrimination Intent by Previous MSM Contact

Participants who had previous contact with MSM scored lower on measures of stereotypes, fear, prejudice, and discrimination intent than participants who did not have previous contact with MSM (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) test on stigma-related variables

| Stereotypes | Fear | Prejudice | Discrimination intent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous MSM contact | ||||

| F(1,1023) = 6.22**, | F(1,1023) = 11.22***, | F(1,1023) = 15.34***, | F(1,1023) = 18.10***, | |

| No | M(SD) = 2.94(0.85)a | M(SD) = 2.71(0.86)a | M(SD) = 2.85(0.66)a | M(SD) = 2.41(0.79)a |

| Yes | M(SD) = 2.65(1.08)a | M(SD) = 2.39(1.02)a | M(SD) = 2.55(0.81)a | M(SD) = 2.07(0.82)a |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age | F(8,1023) = 1.62, | F(8,1023) = 0.71, | F(8,1023) = 0.78, | F(8,1023) = 1.96*, |

| r = 0.04 | r = −0.07 | r = 0.00 | r = 0.79 | |

| Gender | F(1,1023) = 0.52, | F(1,1023) = 13.75***, | F(1,1023) = 4.02*, | F(1,1023) = 20.56*** |

| Male | M(SD) = 2.87(0.92) | M(SD) = 2.74(0.92)a | M(SD) = 2.80(0.71)a | M(SD) = 2.43(0.88)a |

| Female | M(SD) = 2.91(0.87) | M(SD) = 2.64(0.87)a | M(SD) = 2.82(0.68)a | M(SD) = 2.33(0.76)a |

| Religion | F(2,1023) = 103.74***, | F(2,1023) = 35.53***, | F(2,1023) = 99.75***, | F(2,1023) = 20.21***, |

| Muslim | M(SD) = 3.20(0.84)a,b | M(SD) = 2.84(0.89)a,b | M(SD) = 3.03(0.63)a,b | M(SD) = 2.49(0.84)a,b |

| Buddhist | M(SD) = 2.36(0.64)a | M(SD) = 2.39(0.77)a | M(SD) = 2.46(0.57)a | M(SD) = 2.14(0.63)a |

| Other | M(SD) = 2.37(0.80)b | M(SD) = 2.31(0.83)b | M(SD) = 2.36(0.67)b | M(SD) = 2.12(0.75)b |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Year of study | F(5,1023) = 2.47*, | F(5,1023) = 2.44*, | F(5,1023) = 0.80, | F(5,1023) = 3.01**, |

| r = −0.10 | r = −0.16 | r = −0.11 | r = −0.13 | |

| Training status | F(1,1023) = 4.64*, | F(1,1023) = 0.37, | F(1,1023) = 0.13, | F(1,1023) = 0.53, |

| Pre-clinical | M(SD) = 3.00(0.83)a | M(SD) = 2.82(0.86) | M(SD) = 2.91(0.62) | M(SD) = 2.48(0.79) |

| Clinical | M(SD) = 2.84(0.91)a | M(SD) = 2.59(0.89) | M(SD) = 2.76(0.72) | M(SD) = 2.30(0.80) |

| Area of study | F(1,1023) = 1.48, | F(1,1023) = 29.66***, | F(1,1023) = 21.39***, | F(1,1023) = 53.53***, |

| Dental | M(SD) = 2.90(0.86) | M(SD) = 2.77(0.87)a | M(SD) = 2.86(0.67)a | M(SD) = 2.48(0.78)a |

| Medicine | M(SD) = 2.90(0.92) | M(SD) = 2.53(0.89)a | M(SD) = 2.74(0.71)a | M(SD) = 2.18(0.79)a |

p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001.

Letters with matching superscripts were statistically significantly different in post hoc analyses.

Means and standard deviations are included for categorical variables, and correlation coefficients are included for continuous variables to describe the direction of the association

To determine whether associations between previous contact with MSM and any of the stigma-related variables were moderated by socio-demographic or clinical characteristics, a supplementary MANOVA was conducted including interaction terms between previous MSM contact and all socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. Only one interaction term was statistically significant, suggesting that age moderated the effect of previous contact with MSM on prejudice [F(7,1023) = 2.25, \,p = 0.03, \,\eta_{p}^{2} = 0.02]. This interaction term was probed using PROCESS, a computational tool for testing moderation and mediation that can be executed as a macro within SPSS [25]. PROCESS generates the conditional effects of a predictor variable on an outcome variable at different values of a moderating variable, and identifies the value of the moderating variable at which the effect of the predictor variable on the outcome variable changes from significance to non-significance. Results suggest that previous contact with MSM is significantly associated with decreased prejudice across students’ ages, but there is a small trend for the effect to be stronger at older ages. Overall, analyses suggest that students with previous MSM contact score lower on stigma-related variables regardless of their socio-demographic and clinical characteristics.

Mediational Process Linking Previous MSM Contact with Prejudice and Discrimination Intent

Results from the path model (Table 3) further confirmed that students who had contact with MSM endorsed stereotypes to a lesser extent and felt less fear. In turn, students who endorsed stereotypes to a lesser extent and who felt less fear also felt less prejudice. Finally, students who felt less prejudice also had lower intentions to discriminate against MSM. Tests of the indirect effects suggested that previous MSM contact was associated with lower discrimination intent via the mediators of fear and prejudice operating in serial. In addition, the indirect effect of previous MSM contact on discrimination intent via stereotypes and prejudice operating in serial was marginally statistically significant (p = 0.07), even though the indirect effect of stereotypes on prejudice was significant (p = 0.03). Conceptually, this finding suggests that students who have had contact with MSM are less fearful of and endorse stereotypes of MSM to a lesser extent. These students, in turn, endorse less prejudice toward MSM. Finally, students who are less prejudiced toward MSM have lower intentions to discriminate against MSM. Analyses further suggest that reductions in fear may play a slightly stronger role than reductions in stereotypes on discrimination intentions.

Table 3.

Results of path model

| Stereotypes | Fear | Prejudice | Discrimination intent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||

| Previous MSM contact | −0.19 (0.08)*a | −0.26 (0.09)**b | −0.12 (0.04)** | −0.16 (0.04)*** |

| Stereotypes | 0.28 (0.03)***c | 0.10 (0.04)** | ||

| Fear | 0.20 (0.02)***d | 0.29 (0.03)*** | ||

| Prejudice | 0.21 (0.05)***e | |||

| Indirect effects | ||||

| Contact → Stereotypes | −0.05 (0.03)* | |||

| Contact → Fear | −0.05 (0.02)** | |||

| Contact → Stereotypes → Prejudice | −0.01 (0.01)† | |||

| Contact → Fear → Prejudice | −0.01 (0.01)* | |||

| R2 | 0.22 (0.03)*** | 0.13 (0.04)*** | 0.47 (0.04)*** | 0.34 (0.03)*** |

p = 0.07;

p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001;

Superscripts refer to paths in Fig. 1; Analysis control for age, gender, religion, year of study, training status, area of study

Discussion

Malaysian medical and dental students who had previously interacted with MSM were less prejudiced toward MSM and reported lower intentions to discriminate against them within healthcare contexts than students who had not interacted with MSM. Results suggest that students who interact with MSM may gain knowledge about MSM that combats stereotypes, and may become less anxious and fearful about interacting with MSM. These decreased stereotypes and fear relate to lower prejudice, which, in turn, relates to lower discrimination intentions. Results further provide insight into which Malaysian medical and dental students have had less contact with MSM, who may be targeted for prejudice reduction interventions. Students who were younger, female, Malay, and Muslim reported less contact with MSM than students who were older, male, of other ethnicities, and of other religions. Additionally, students who were less advanced in their studies, preclinical status, and studying dentistry reported less contact with MSM than students who were more advanced, clinical status, and studying medicine. Multivariate analyses highlighted particularly strong associations between religion with prejudice and discrimination intent.

Strengths and Weaknesses

The study focuses on MSM stigma in Malaysia, where societal stigma toward MSM is strong and structurally manifested via policies that punish same-sex sexual acts with incarceration, physical violence, and fines [7]. Similar to countries with strong societal MSM stigma, HIV rates among MSM are rising in Malaysia [1, 2, 17]. Finding ways to ensure safe and non-stigmatizing HIV prevention and treatment services for MSM within Malaysian healthcare settings is therefore critical. This study further focuses on associations between contact with MSM and MSM stigma. Unlike other factors associated with MSM stigma among Malaysian medical and dental students, such as religion, contact experiences can be changed. Interventions can focus on increasing prosocial contact with MSM to reduce MSM stigma. Additionally, this study includes a large sample of medical and dental students who represent future healthcare providers in Malaysia. These students may be appropriate targets for intervention, with intervention content potentially incorporated into undergraduate curriculum.

The current study is cross-sectional, which limits our ability to determine causal associations between variables. Meta-analytic evidence on the contact hypothesis, including results from 38 countries and experimental studies, suggests that contact leads to lower prejudice [14]. Yet, experimental and longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether contact causes reductions in prejudice toward MSM among Malaysian medical and dental students. Future experimental and longitudinal studies can also continue to examine the psychological processes linking contact with reduced prejudice. The current work focuses on stereotypes and fear as proxies for knowledge and anxiety, which are identified as mechanisms whereby contact reduces prejudice [15]. The effect of interpersonal contact on prejudice via stereotypes was significant. The effect of contact on discrimination intent via stereotypes, however, was marginally significant, suggesting the need for further research to determine the magnitude of the impact of reduced stereotypes on discrimination specifically. This study does not measure empathy, a third mechanism whereby contact may reduce prejudice [15]. Future studies should explore the roles of knowledge, anxiety, and empathy in associations between contact and prejudice to build stronger understanding of how contact may affect prejudice.

Approximately 41 % of students emailed accessed the link and 37 % completed the survey. Although this response rate is comparable to other online studies, future work might distribute the survey in other ways (e.g. via internet-based learning platforms frequently accessed by students) and offer an incentive for survey completion to encourage a higher response rate [26]. Additionally, the item measuring previous MSM contact referred to “homosexuals” generally whereas all other items in the survey referred to MSM specifically. The contact item, therefore, may reflect contact with MSM as well as other sexual minorities. Future work should differentiate between contact with gay, lesbian, bisexual, and other sexual minority individuals to better understand the impact of contact with these specific group members on healthcare providers.

Future Directions: Intervention Implications

Interventions to eliminate MSM stigma among future healthcare providers are needed to enhance HIV treatment and prevention strategies for MSM in Malaysia and other countries where societal MSM stigma is strong and where HIV rates are rising among MSM [1, 2, 6, 7, 17]. Such interventions may be integrated into medical and dental school curricula to reduce prejudice among future providers. Research on the contact hypothesis provides guidance on the optimal conditions under which contact should take place to reduce prejudice [12, 14, 15]. These include fostering intergroup cooperation, establishing common goals, assuring equal status, and gaining support from authorities. For example, students could work with MSM or staff members from MSM-centric service organizations to develop strategies for HIV prevention. The complementary strengths and expertise of students and MSM could be emphasized. It may be possible to draw support for these activities from students’ universities (e.g. professors, school administrators) even if support is lacking in society. Campus-wide policies may help protect MSM students from discrimination. In contexts wherein contact is not feasible due to safety risks to MSM, it may be possible to facilitate indirect contact in classrooms via educational material such as books, videos and video-conferencing. Certain media interventions, which have proven effective in other contexts [27, 28], may be challenging in Malaysia where the government controls major media outlets and prohibits gay characters [20].

Combating MSM stigma in healthcare contexts must be prioritized in this “next wave of global HIV” [2]. Providing opportunities for interpersonal interaction between medical and dental students with MSM, under MSM-affirmative conditions, may reduce prejudice and discrimination toward MSM among these future healthcare providers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12 HS022986 for VAE); the Downs International Health Student Travel Fellowship (for HJ); the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia’s High Impact Research Grant (E000001-200001 for AK, UM.C/625/1/HIR/MOHE/DENT/07 for JJ); and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA025943 for JAW, AK, FLA; K24 DA017072 for FLA; K01 DA038529 for JAW; NIDA-International AIDS Society Award for SHL). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. The authors would like to thank Drs. Petrick Periyasamy, Samsul Draman, Lela Hj Suut, Lahari Telang, Tan Su Keng, and Azirrawani Ariffin for coordinating participant recruitment at their respective universities.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380:367–377. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyrer C, Sullivan P, Sanchez J, et al. The increase in global HIV epidemics in MSM. AIDS. 2013;27:2665–2678. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000432449.30239.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyrer C, Sullivan PS, Sanchez J, et al. A call to action for comprehensive HIV services for men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380:424–438. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61022-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altman D, Aggleton P, Williams M, et al. Men who have sex with men: stigma and discrimination. Lancet. 2012;380:439–445. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60920-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goffman ES. Notes on the management of spoiled identity. 1st ed. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beyrer C. Pushback: the current wave of anti-homosexuality laws and impacts on health. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itaborahy LP, Zhu J. A world survey of laws: criminalization, protection and recognition of same-sex love. Geneva: ILGA—International Lesbian Gay Bisexual Trans and Intersex Association; 2014. www.ilga.org. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beyrer C, Baral SD. MSM, HIV and the law: the case of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM); Working paper for the third meeting of the Technical Advisory Group of the Global Commission on HIV and the Law; 2011. Jul 7–9, [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poteat T, Diouf D, Drame FM, et al. HIV risk among MSM in Senegal: a qualitative rapid assessment of the impact of enforcing laws that criminalize same sex practices. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson JE, Kanters S. Lack of sexual minorities’ rights as a barrier to HIV prevention among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Asia: a systematic review. LGBT Health. 2015;2:16–26. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Am Psychol. 2013;68:225–236. doi: 10.1037/a0032705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Cambridge: Perseus Books; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tajfel H, Billig MG, Bundy RP, Flament C. Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1971;1:149–178. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;90:751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2008;38:922–934. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brewer MB. The social psychology of intergroup relations: social categorization, ingroup bias, and outgroup prejudice. In: Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Social psychology: handbook of basic principles. New York: The Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ngadiman S, Suleiman A, Taib SM, Yuswan F. Malaysia 2014: country responses to HIV/AIDS. HIV/STI Section of Ministry of Health Malaysia. 2014 http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents//MYS_narrative_report_2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanter J, Koh C, Razali K, et al. Risk behaviour and HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in a multiethnic society: a venue-based study in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22:30–37. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim SH, Bazazi AR, Sim C, Choo M, Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A. High rates of unprotected anal intercourse with regular and casual partners and associated risk factors in a sample of ethnic Malay men who have sex with men (MSM) in Penang, Malaysia. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:642–649. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams WL. Islam and the politics of homophobia: the persecution of homosexuals in Islamic Malaysia compared to secular China. In: Harib S, editor. Islam and homosexuality. 1st ed. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baharom H. Najib: LGBTs, liberalism, pluralism are enemies of Islam. [Accessed 3 Jan 2015];Malays Insid. 2012 http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/najib-lgbts-liberalism-pluralism-are-enemies-of-islam. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Profile: Anwar Ibrahim. [Accessed 6 Nov 2014];BBC news Asia. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-16440290. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein JA, Li L. Measuring HIV-related stigma among Chinese service providers: confirmatory factor analysis of a multidimensional scale. AIDS Behav. 2007;12:789–795. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9339-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janke R. Effects of mentioning the incentive prize in the email subject line on survey response. Evid Based Libr Inf Pract. 2014;9:4–13. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paluck EL, Green DP. Prejudice reduction: what works? A review and assessment of research and practice. Ann Rev Psychol. 2009;60:339–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paluck EL. Reducing intergroup prejudice and conflict using the media: a field experiment in Rwanda. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96:574–587. doi: 10.1037/a0011989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]