Abstract

Background & Aims

Little is known in the United States (US) about the epidemiology of liver diseases that develop only during (are unique to) pregnancy. We investigated the incidence of liver diseases unique to pregnancy in Olmsted County, MN and long-term maternal and fetal outcomes.

Methods

We identified 247 women with liver diseases unique to pregnancy from 1996 through 2010 using the Rochester Epidemiology Project database. The crude incidence rate was calculated by the number of liver disease cases divided by 35,101 pregnancies.

Results

Of pregnant women with liver diseases, 134 had preeclampsia with liver dysfunction, 72 had hemolysis-associated increased levels of liver enzymes and low-platelet (HELLP) syndrome, 26 had intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, 14 had hyperemesis gravidarum with abnormal liver enzymes, and 1 had acute fatty liver of pregnancy. The crude incidence of liver diseases unique to pregnancy was 0.77%. Outcomes were worse among women with HELLP or preeclampsia than the other disorders—of women with HELLP, 70% had a premature delivery, 4% had abruptio placentae, 3% had acute kidney injury, and 3% had infant death. Of women with preeclampsia, 56.0% had a premature delivery, 4% had abruptio placentae, 3% had acute kidney injury, and 0.7% had infant death. After 7 median years of follow up (range, 0–18 years), 14% of the women developed recurrent liver disease unique to pregnancy; the proportions were highest in women with initial hyperemesis gravidarum (36%) or intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (35%). Women with preeclampsia were more likely to develop subsequent hepatobiliary diseases.

Conclusion

We found the incidence of liver disease unique to pregnancy in Olmsted County, MN to be lower than that reported from Europe or US tertiary referral centers. Maternal and fetal outcomes in Olmsted County were better than those reported from other studies, but fetal mortality was still high (0.7%–3.0%). Women with preeclampsia or HELLP are at higher risk for peri-partum complications and subsequent development of comorbidities.

Keywords: AFLP, ICP, risk factor, neonate

Liver diseases are potentially serious complications of pregnancy, which can lead to various maternal and perinatal morbidities with potentially serious consequences including maternal or fetal death1, 2. Liver diseases of pregnancy (LDoP) include intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) and HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets) syndrome. In addition, hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) and preeclampsia (PE) are frequently associated with liver abnormalities.

The epidemiology of the five LDoP is not well studied, particularly in the US. Currently available information about LDoP is derived mostly from tertiary referral centers and population-based studies from Europe3, 4. ICP has been described in 0.2-0.3% of pregnancies in the US5, 6, 1.5% in Europe 7 and up to 6.5% in Chile 8. ICP can be associated with prematurity9-11, stillbirths12, and subsequent maternal liver disease13. HELLP syndrome has been reported in 0.2-0.6% of pregnancies 14, while AFLP occurs less frequently at 1/13,000- 15,000 deliveries 15. Both conditions are associated with worse maternal and fetal outcomes than ICP, particularly if they are not recognized in a timely manner16, 17. It has been described that HG occurs in 0.3% of pregnancies and 50% of cases have liver tests abnormalities2, 18. PE affects 2-8% of pregnancies and is directly associated with 10-15% of maternal deaths. Liver involvement in PE may herald significant maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality 19.

To the degree that most of these clinical outcome data in the US are accumulated at academic practices, the reports may be skewed towards the more severe end of the spectrum. Population-based studies have demonstrated that in many disease categories, referral center-based studies overestimate the incidence and disease severity. Furthermore, long-term studies of LDoP recurrence rates and subsequent development of hepatobiliary disease in US communities are lacking. Epidemiologic data would provide useful guidance in clinical decision making and patient counseling in regards to immediate and long term outcomes.

In light of the paucity of literature on this topic, particularly in the US, we used population-based data from Olmsted County, MN to determine: 1) the incidence of LDoP in the community; 2) the maternal and fetal outcomes in LDoP; and 3) long term prognosis, including recurrent LDoP and subsequent development of hepatobiliary and other medical conditions.

Methods

Data source

Population-based epidemiological research can be conducted in Olmsted County, Minnesota, because medical care is effectively self-contained within the community and there are only a few providers. As of 2010, the Olmsted County population included 144,428 people, of which 85.7% were white and 48.9% were male. Currently, the medical providers include Mayo Clinic and its affiliated hospitals, Olmsted Medical Center and its affiliated hospital, and the Rochester Family Clinic, a private practitioner in the area. Importantly, all medical information from each of these providers for each individual resident of Olmsted County is linked to a single identification number allowing linkage across health-care systems. The diagnoses recorded in billing data from each institution are indexed so that all individuals with any specific diagnosis can be identified across system and the corresponding patient records can easily be retrieved from each site.

The system and infrastructure that collects, collates and indexes the data is the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP)20, 21, which has been funded by the National Institutes of Health since 1966.

Patient selection

Using the REP, we constructed a community cohort of all pregnancies in Olmsted County, MN from 1996 to 2010. Women with a diagnosis of LDoP were identified by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes and Hospital International Classification of Diseases Adapted (HICDA) codes (a system developed at Mayo for research diagnosis coding from 1976 – 2010) described in the Supplementary Table. Because only three of the five LDoP diagnoses have specific diagnostic codes (namely PE, HELLP and HG), AFLP and ICP were searched under the non-specified category of “Liver diseases of pregnancy” (ICD-9 code 646.7).

Of all providers in Olmsted County, Mayo Clinic delivers specialty care, including high-risk obstetrics, making it more likely that their practice is enriched with patients with LDoP. Further search of the Mayo database using Data Discovery and Query Builder (DDQB) was performed, to enhance the ascertainment of LDoP cases, particularly the two non-coded diagnoses, namely AFLP and ICP. DDQB is an advanced query tool that allows access to a clinical data warehouse (Mayo Clinic Life Sciences System), such as patient demographics, clinical notes, diagnosis data and laboratory test results. This tool allowed the identification of an additional small number of women with ICP, who were Olmsted County residents, and who would have been missed due to lack of a specific ICD-9 code.

All available liver tests (ALT, AST and bilirubin) of all pregnant women identified by the above algorithm were electronically extracted from the laboratory database. Patients with AST >40 U/L, ALT>40 U/L or total bilirubin >1 mg/dL during pregnancy were identified and included in the final cohort of patients with a diagnosis code of LDoP. Medical records of each subject included in this cohort were reviewed in detail (outpatient and hospital notes, images, laboratory studies) to confirm the LDoP diagnosis and to exclude other conditions captured under the ICD-9 code 646.7 (the broader category of liver diseases of pregnancy), which were not in fact LDoP.

Table 1 summarizes the definitions used to identify LDoP cases. Subjects with known liver diseases such as acute and chronic hepatitis, alcoholic or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Budd-Chiari syndrome, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, gallbladder diseases or prior liver transplant were excluded.

Table 1. Definitions of liver diseases of pregnancy.

| Diagnosis | Definition |

|---|---|

| Hyperemesis gravidarum with liver dysfunction22 | Elevated liver enzymes or bilirubin in the presence of persistent vomiting for more than one week during the first or second trimester. |

| Pre-eclamptic liver dysfunction23 | Elevated liver enzymes or bilirubin in the presence of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema after 20 weeks of gestation. |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP)24 | Pruritus with elevated serum transaminases and/or bile acids in the second or third trimester. |

| HELLP syndrome25, 26 | (1) elevated AST >40 U/L, (2) low platelet count <150×109/L, and (3) absence or presence of hemolysis (lactate dehydrogenase >600 U/L). |

| Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP)27 | Six or more of the following features in the absence of another explanation: (1) vomiting, (2) abdominal pain, (3) polydipsia/polyuria, (4) encephalopathy, (5) elevated bilirubin, (6) hypoglycemia, (7) elevated urate, (8) leukocytosis, (9) ascites or bright liver on ultrasound scan (USS), (10) elevated transaminases, (11) elevated ammonia, (12) renal impairment, (13) coagulopathy or (14) microvesicular steatosis on liver biopsy. |

Data Analysis

The study outcomes included maternal, fetal and neonatal death, prematurity, and rates of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission. Long term outcomes such as recurrent LDoP, subsequent development of hepatobiliary and other medical conditions were also extracted from the REP database.

In calculating incidence rates LDoP in the community, all pregnancies identified in the REP database were considered to be the population at risk (as some women had more than one pregnancy). The crude incidence rate was calculated by the number of cases of each LDoP category (including recurrences within the study period) divided by the total number of pregnancies. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Mayo Clinic and the Olmsted Medical Center.

Results

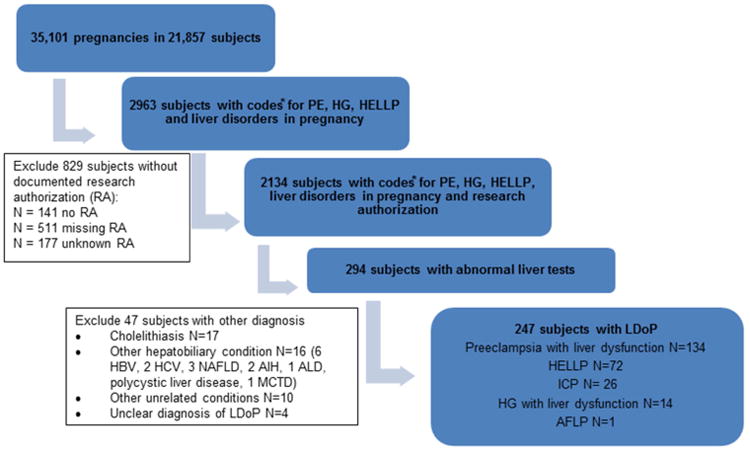

Between January 1st 1996 and December 31st 2010, a total of 35,101 pregnancies were identified in 21,857 women in Olmsted County. From this cohort, 2,963 women with a prespecified diagnosis code of PE, HELLP, HG and the broader category of “liver disorders of pregnancy” were identified, 829 of whom did not grant research authorization and were excluded from the study (Figure 1). Of the remaining 2,134 subjects, 294 had abnormal liver tests during pregnancy. After detailed review of their medical records, we further excluded 47 subjects with an alternate hepatobiliary disease, who otherwise would have been captured under the ICD code of “liver disorders of pregnancy”. The final cohort of patients with LDoP who met the case definition shown in Table 1 included 247 subjects, who were followed until July 1st 2014.

Figure 1.

Selection of patients with liver diseases of pregnancy from the community. PE: preeclampsia; HG: hyperemesis gravidarum; HELLP: hemolysis- elevated liver tests- low platelets syndrome; ICP: intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy; AFLP: acute fatty liver of pregnancy; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; AIH: autoimmune hepatitis; ALD: alcoholic liver disease; MCTD: mixed connective tissue disease.

PE with liver dysfunction was the most common condition (134 subjects), followed by HELLP (72 subjects), ICP (26 subjects), HG with abnormal liver tests (14 subjects) and AFLP (1 subject). To calculate the incidence of LDoP, the number of recurrent LDoP with subsequent pregnancies within the study time frame was included (8 PE, 8 HELLP, 6 ICP and 4 HG). The crude incidence of LDoP was 0.77% (1 in 130 pregnancies), HELLP 0.23% (1 in 435 pregnancies), PE 0.40% (1 in 250 pregnancies), ICP 0.10% (1 in 1000 pregnancies), HG 0.05% (1 in 2000 pregnancies).

Table 2 describes the demographic, clinical and obstetric characteristics of patients. The median age was 29 (range 25-33) and 80% were Caucasian. The majority of women (63%) were nulliparous, except for women with ICP. Most of the subjects (87%) had a single fetus, largely without gender preponderance. The LDoP was diagnosed at a median gestational age of 35 weeks, earlier for HG (12 weeks) and for AFLP (26 weeks). Patients with HELLP, AFLP and PE with liver dysfunction delivered within the same week from diagnosis. Subjects with ICP delivered within 2.5 weeks from diagnosis (median gestational age 37.5 weeks). All patients with HG and liver dysfunction delivered at term (37- 40 weeks). Gestational diabetes coexisted in 15% of women with ICP. Preexisting medical conditions were most common in women with PE.

Table 2. Patient demographic, clinical and obstetric characteristics.

| Characteristic | ICP N=26 |

PE with liver dysfunction N=134 |

HELLP N= 72 |

AFLP N=1 |

HG with liver dysfunction N= 14 |

Total N= 247 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, median (IQR) | 29 (26-31) | 29 (24-35) | 29 (26- 33) | n/a* | 26 (22-26) | 29 (25-33) | |

| Race | Caucasian | 23 (88%) | 98 (75%) | 61 (87%) | n/a* | 10 (72%) | 193 (80%) |

| African-American | 0 | 10 (8%) | 4 (6.0%) | 1 (7%) | 15 (6%) | ||

| Asian/PI | 1 (4%) | 10 (8%) | 2 (3.0%) | 0 | 13 (6%) | ||

| Other | 2 (8%) | 12 (9%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (21%) | 20 (8.0%) | ||

| Obstetric characteristics | |||||||

| Nulliparous | 7 (27%) | 92 (69%) | 48 (67%) | 0 | 8 (57%) | 155 (63%) | |

| Single fetus | 22 (92%) | 114 (86%) | 61 (86%) | 1 (100%) | 14 (100%) | 212 (87%) | |

| Male fetus | 13 (52%) | 58 (43%) | 37 (51%) | 0 | 4 (31%) | 112 (46%) | |

| History of LDoP | 2 (8%) | 2 (1.5%) | 2 (3%) | 0 | 1 (8%) | 7 (3%) | |

| Gestational age at diagnosis (weeks) | 35 (33-37) | 36 (33-37)∞ | 35 (32-37) | 26 (26-26) | 12 (7-15) | 35 (32-37) | |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 37.5 (37-38) | 36 (34-38) | 35 (32-37) | 26 (26-26) | 37.5 (37-40) | 36 (33-38) | |

| Gestational diabetes | 4 (15%) | 13 (10%) | 6 (9%) | 0 | 0 | 23 (9%) | |

| Preexisting clinical characteristics | |||||||

| BMI, median (IQR) | 22 (21-29) | 26 (22-30) | 23 (21-27) | n/a | 20 (20-20) | 24 (21-29) | |

| Obesity | 0 | 11 (8%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (8%) | 14 (6%) | |

| Preexisting HTN | 2 (8%) | 14 (11%) | 5 (7%) | 0 | 0 | 21 (9%) | |

| DM | 0 | 3 (2%) | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.5%) | |

The age and race of the patient with AFLP were not disclosed to maintain patient confidentiality

There were 2 patients diagnosed with PE postpartum. One patient with pregnancy induced hypertension presented with symptomatic hypertension and elevated liver tests (AST 171 U/L, ALT 196 U/L) 3 days after delivery. The second patient had preeclampsia with normal liver tests at the time of delivery, but was found to have persistent hypertension and mildly elevated AST (73 U/L) 5 days after delivery.

The most common symptoms at LDoP diagnosis are presented in Table 3. Patients with ICP presented with typical intractable pruritus, largely without additional symptoms. Symptoms leading to the diagnosis of PE with liver dysfunction were nonspecific and present in a minority of patients; headache was the most common symptom, noted in 32% of cases, followed by abdominal pain (20%) and nausea/vomiting (10%). Abdominal pain was the leading presentation in cases of HELLP and AFLP. The patient with AFLP presented with acute onset of epigastric and left hypochondrial pain at 26 weeks gestation. She did not have nausea/vomiting, HTN, proteinuria or thrombocytopenia. Abdominal pain was common in patients HG with liver dysfunction (48%) in addition to nausea and vomiting.

Table 3. Clinical presentation at LDoP diagnosis and immediate complications.

| Symptom | ICP N=26 |

PE with liver dysfunction N=134 |

HELLP N= 72 |

AFLP N=1 |

HG with liver dysfunction N= 14 |

Total N= 247 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea/vomiting | 1 (4%) | 13 (10%) | 16 (23%) | 0 | 14 (100%) | 44 (18%) |

| Headache | 0 | 42 (32%) | 19 (27%) | 0 | 0 | 61 (25%) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (4%) | 27 (20%) | 34 (48%) | 1 (100%) | 7 (50%) | 70 (29%) |

| ALT (U/L) | 69 (49-349) | 42 (27-82) | 214 (100-371) | 211 (211-211) | 96 (49-225) | 66 (37-189) |

| AST (U/L) | 57 (42-100) | 57 (45-96) | 240 (138-389) | 386 (386-386) | 52 (34-106) | 81 (47-197) |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.6 (0.5-1.0) | 0.4 (0.3- 0.6) | 0.6 (0.4-0.7) | 0.9 (0.9-0.9) | 0.9 (0.6-1.1) | 0.5 (0.4-0.8) |

| Abruptio placentae | 0 | 6 (4%) | 3 (4%) | 0 | 0 | 9 (4%) |

| Acute kidney injury | 0 | 4 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 6 (2%) |

The highest ALT and AST levels were found in HELLP and AFLP, followed by HG. The patient with AFLP had a peak ALT of 386 U/L shortly after admission, which returned to normal 3 days after urgent delivery. None of the subjects in this LDoP cohort, including those with ICP, had jaundice or abnormal bilirubin. Ursodeoxycholic acid was used in 46% of patients with ICP. There were no major complications such as multi-organ failure, encephalopathy, disseminated intravascular coagulation, liver hematoma or intra-abdominal bleeding. Abruptio placentae (4%) and acute kidney injury (3%) were present in a minority of patients with PE and HELLP. There were no maternal deaths.

Table 4 summarizes obstetric and neonatal outcomes. Overall, 44% of pregnancies were delivered by cesarian sections. The majority of subjects with HELLP (70%) and PE (56%) delivered prematurely. There was one spontaneous premature rupture of membranes in a patient with ICP. The remaining ICP cases were delivered at term, 4 via cesarian sections and 22 vaginal deliveries, 17 of which were induced. There were nine fetal deaths: five in utero and four postpartum. Most of the intrauterine deaths resulted from pregnancies complicated by PE: two miscarriages (infant death prior to 24 weeks gestation) and two cases of stillbirth (infant death after 24 weeks gestation). There was one miscarriage in a patient with HG, and another patient elected for early termination of pregnancy due to intractable nausea and vomiting. Four infants died after delivery (neonatal case fatality rate, NCFR = 1.6%); two infants from two mothers with HELLP (NCFR=3%), one from a mother with PE with liver dysfunction (NCFR=0.7%), and the infant born from the mother with AFLP. Almost one third of infants (31%) required neonatal intensive care after delivery.

Table 4. Obstetric and neonatal outcomes in patients with LDoP.

| Outcome | ICP N= 26 |

PE with liver dysfunction N= 134 |

HELLP N= 72 |

AFLP N= 1 |

HG with liver dysfunction N= 14 |

Total N= 247 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OBSTETRIC OUTCOMES | ||||||

| Cesarian section | 4 (17%) | 68 (51%) | 34 (47%) | 1 (100%) | 1 (8%) | 108 (44%) |

| Premature delivery‡ | 1 (4%) | 75 (56%) | 50 (70%) | 1 (100%) | 2 (14%) | 129 (53%) |

| NEONATAL OUTCOMES | ||||||

| Infant death | 0 | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (100%) | 0 | 4 (1.6%) |

| Miscarriagea | 0 | 2 (1.5%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (7%) | 3 (1%) |

| Stillbirth* | 0 | 2 (1.5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.8%) |

| Overall fetal mortality rate∞ | 0 | 5 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (100%) | 1 (7%) | 9 (4%) |

| NICU admission | 0 | 42 (32%) | 31 (44%) | 1 (100%) | 0 | 74 (31%) |

| RECURRENT LDoP | ||||||

| % subjects with recurrent LDoP | 35% | 10% | 14% | 0 | 36% | 14% |

| % subsequent pregnancies with recurrent LDoP | 63% (10/16) | 12% (12/102) | 17% (11/63) | 0% (0/11) | 64% (7/11) | 21% (40/193) |

Live delivery before 37 weeks gestation

Intrauterine death before 24 weeks gestation

Intrauterine death after 24 weeks gestation

Includes infant death, miscarriage and stillbirth

The patients were followed for a median of 7 years (range 0-18 years). During this time, 14% of patients developed recurrent LDoP. The highest recurrence rate was noted in HG (36% of subjects, 64% of subsequent pregnancies) and ICP (35% of subjects, 63% of subsequent pregnancies), followed by HELLP (14% of subjects, 17% of subsequent pregnancies). Patients with PE with liver dysfunction had the lowest recurrence rate (10% of subjects, 12% of subsequent pregnancies). Notably, 3 of the 10 subjects with HELLP had PE as recurrent LDoP. Similarly, in 2 of the 13 patients with PE the recurrent LDoP was HELLP.

Table 5 illustrates subsequent liver and non-liver related diseases in women with LDoP. During the study follow-up, hepatobiliary diseases were diagnosed in 7% of women with PE with liver dysfunction and 4% of subjects with HELLP. One patient with ICP was subsequently diagnosed with idiopathic sclerosing cholangitis. One patient with HG was later diagnosed with hepatitis B. The proportion of women who subsequently developed other (non-liver related) medical conditions was highest in subjects with PE with liver dysfunction (10% HTN, 6% obesity, 3% diabetes, 3% hyperlipidemia). Interestingly, obesity (ICD- 9 code 278.00) was subsequently recorded in 23% of women with HG with liver dysfunction.

Table 5.

Subsequent hepatobiliary and non-liver related diseases in patients with liver diseases of pregnancy.

| Subsequent diseases | ICP N= 26 |

PE with liver dysfunction N= 134 |

HELLP N= 72 |

AFLP N=1 |

HG with liver dysfunction N= 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatobiliary disease | Idiopathic sclerosing cholangitis (1) | Cholelithiasis (4) Cholecystitis (1) NAFLD (4) | Cholelithiasis (2) NAFLD (1) | Cholelithiasis | Hepatitis B |

| HTN | 0 | 14 (10%) | 2 (3%) | 0 | 1 (8%) |

| DM | 0 | 4 (3%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 | 0 |

| Obesity | 0 | 8 (6%) | 4 (5%) | 0 | 3 (23%) |

| HLD | 0 | 4 (3%) | 3 (4%) | 0 | 0 |

| PIH | 0 | 3 (2%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

In this first population-based cohort study of LDoP in the US, the overall incidence of LDoP was 0.77% of pregnancies. Preeclampsia with liver dysfunction was the most common (0.40%), followed by HELLP (0.23%) and ICP (0.10%). HG with liver abnormalities was present in 0.05% of pregnancies, while AFLP was diagnosed in only one patient during the study timeframe. While maternal deaths were not observed, the overall fetal mortality rate was 4% in patients with PE, 3% in patients with HELLP and 100% in the one case with AFLP. HG had the highest recurrence rate in subsequent pregnancies (64%), followed by ICP (63%) and HELLP (17%). While subsequent hepatobiliary diseases and other medical conditions were not common, they were most likely to develop in patients with PE and HELLP.

Accurate and generalizable data on the epidemiology of LDoP are scarce for several reasons. First, in general, population-based epidemiological data are difficult to obtain in the US. With a few exceptions such as the REP, it is nearly impossible to reliably collect information derived from health care in a defined population, which is provided by multiple hospitals and providers that do not share a common data system. Second, data about relatively rare conditions that require specialty care such as LDoP are studied at academic referral centers, represent the more severe end of the disease spectrum and overestimate the impact of the disease. This referral bias (Berkson bias) has been identified previously for many conditions 28. In addition, the lack of specific diagnosis codes for each of the LDoP conditions limits the accuracy of studies derived from administrative data29, which use the broad diagnosis code of “liver diseases of pregnancy” (ICD-9 code 646.7) and may include other hepatobiliary conditions which are not unique to pregnancy. Indeed, by manual review of their medical records, we excluded a large number of subjects with abnormal liver tests during pregnancy (47 out of 294), due to acute biliary conditions and chronic hepatitis which were captured under ICD-9 codes used for liver diseases unique to pregnancy. Third, there may be geographic variation in the incidence of LDoP, related to racial and ethnic composition of the population. The incidence of preeclampsia has been reported to be higher in the southern US, a trend in part attributed to the higher proportion of black women30. Climate may also affect the variability, as the incidence of preeclampsia is associated with conception during the spring and summer months31.

These factors may explain a large part of the variability in the available epidemiological data on LDoP. For example, in our study, derived from a mostly white US population of almost 145,000 people, the overall incidence of LDoP was 0.77%, whereas a prospective study in the UK suggested that the incidence LDoP may be as high as 3%3. On the other hand, we observed better maternal and fetal outcomes than those reported at tertiary referral centers16, 32-34. Although case fatality rate of affected babies was lower, it was substantially higher than that of uncomplicated pregnancies, with a high percentage of a prematurity and neonatal care admission. Recurrence of LDoP was also not as high as tertiary-center reports35.

From the clinical standpoint, it is noteworthy that, despite liver involvement, most of the subjects with PE presented with vague, non-specific symptoms, while those with HELLP more frequently had abdominal pain. A high index of suspicion to recognize these seemingly innocuous presentations may be needed for proper diagnosis, as PE and HELLP had the highest rates of maternal and fetal complications. This underscores the importance of recognizing blood pressure trends and new onset of hypertension during pregnancy, as one of the key signs that will lead to the discovery of liver dysfunction. Congruent with prior studies, ICP was commonly seen with gestational diabetes and recurred frequently in subsequent pregnancies6. We did not find a high incidence of subsequent hepatobiliary diseases, such as cholelithiasis, in women with ICP, in contrast to previous studies that suggested shared genetic susceptibility (e.g., variants in the ABCB4 gene)36,37. We did find a patient with ICP who later developed sclerosing cholangitis – the significance of the observation is uncertain. Finally, PE has been recognized as a marker for future cardiovascular disease, via shared risk factors, persistent endothelial dysfunction38 and target organ damage39. In our cohort, women with liver dysfunction due to PE and HELLP were more likely to have preexisting hypertension and diabetes mellitus and were more prone to subsequent development of an unfavorable metabolic profile. These data provide opportunities for counseling and intervention in women with LDoP to decrease future health risk.

This study has several limitations. While REP is a unique and robust population-based epidemiological resource, our data may not be generalizable to all communities. Compared to the US population, the Olmsted County residents are less ethnically diverse and have a higher socioeconomic status, in general reflecting the Upper Midwest population40. Nevertheless, because of the lack of specificity of diagnostic codes for LDoPs and in the absence of a nationwide database, their epidemiologic description in the United States remains limited to population-based data, such as the REP. While we acknowledge that the findings cannot be generalized to a population of a different racial/ethnical or socioeconomic mix, they are more informative than single-center data, where the incidence and case-severity is biased by tertiary referral.

Second, as our data arose from routine practice, diagnostic investigation and treatment were not standardized. For example, we lacked serum bile acid levels in patients with ICP, which may help assess its severity. It is difficult to gauge whether the favorable outcomes noted in our ICP patients were related to less severe disease, empiric treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid and/or expertise in high-risk obstetrical management of our patients.

Lastly, our study does not describe the full spectrum of liver test abnormalities in pregnancy, but rather the entities unique to pregnancy. Unlike coincidental liver diseases with clinical manifestations (such as biliary disease, viral hepatitis or drug-induced liver injury), or preexisting liver disease (such as viral or autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson's or cholestatic liver disease), the LDoPs are associated with worse outcomes, pose a diagnostic challenge and are generally entities that cause anxiety on the provider's and patient's part. Moreover, the long term hepatic and medical complications of each of the five LDoP entities has not been described in US epidemiologic studies.

In summary, in this first population-based study of LDoP in the US, the incidence of LDoP in this population is not as high as reported in the literature derived from Europe or US tertiary referral centers. The maternal and fetal outcomes are better than reported, but the fetal mortality rate is still high. Women with PE and HELLP are at higher risk for peripartum complications and subsequent development of comorbidities. For gastroenterologists and hepatologists, familiarity of the non-specific presentation and a high index of suspicion are required to make a correct and timely diagnosis. Given subsequent liver and systemic consequences, patient counseling and judicious follow-up are recommended. In the meantime, better understanding of the pathogenesis of these unique disorders is needed for prevention and optimal prognostication for future mothers and their babies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table. ICD-9 and HICDA codes used to select LDoP subjects

Acknowledgments

Funding source: Dr. Kim is supported by a grant from the National institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease (DK-92336).

Abbreviations

- AFLP

acute fatty liver of pregnancy

- DDQB

Data Discovery and Query Builder

- HELLP

hemolysis-elevated liver enzymes-low platelets syndrome

- HG

hyperemesis gravidarum

- HTN

hypertension

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases-9

- ICP

intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- LDoP

liver diseases of pregnancy

- NICU

neonatal intensive care unit

- PE

preeclampsia

- REP

Rochester Epidemiology Project

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

- Study concept and design: AMA, WRK

- Acquisition of data: AMA, JJL, JKR

- Analysis and interpretation of data: AMA, WRK, JJL, JKR, JEH

- Drafting of the manuscript: AMA

- Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: WRK, JEH, BPY

- Approval of the final manuscript: AMA, WRK, JJL, JKR, BPY, KM, JEH

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hay JE. Liver disease in pregnancy. Hepatology. 2008;47:1067–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.22130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riely CA. Liver disease in the pregnant patient. AJG. 1999;94:1728–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ch'ng CL, Morgan M, Hainsworth I, et al. Prospective study of liver dysfunction in pregnancy in Southwest Wales. Gut. 2002;51:876–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight M, Nelson-Piercy C, Kurinczuk JJ, et al. A prospective national study of acute fatty liver of pregnancy in the UK. Gut. 2008;57:951–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.148676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laifer SA, Stiller RJ, Siddiqui DS, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid for the treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. The Journal of maternal-fetal medicine. 2001;10:131–5. doi: 10.1080/714052719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martineau M, Raker C, Powrie R, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of gestational diabetes. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2014;176:80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glantz A, Marschall HU, Mattsson LA. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Relationships between bile acid levels and fetal complication rates. Hepatology. 2004;40:467–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribalta J, Reyes H, Gonzalez MC, et al. S-adenosyl-L-methionine in the treatment of patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with negative results. Hepatology. 1991;13:1084–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bacq Y, Sapey T, Brechot MC, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a French prospective study. Hepatology. 1997;26:358–64. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wikstrom Shemer E, Marschall HU, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and associated adverse pregnancy and fetal outcomes: a 12-year population-based cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120:717–23. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson CE, Shah RR, Gottimukkala S, et al. Primum non nocere: how active management became modus operandi for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geenes V, Chappell LC, Seed PT, et al. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a prospective population-based case-control study. Hepatology. 2014;59:1482–91. doi: 10.1002/hep.26617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marschall HU, Wikstrom Shemer E, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and associated hepatobiliary disease: a population-based cohort study. Hepatology. 2013;58:1385–91. doi: 10.1002/hep.26444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sibai BM, Ramadan MK, Chari RS, et al. Pregnancies complicated by HELLP syndrome: subsequent pregnancy outcome and long-term prognosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:125–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reyes H, Sandoval L, Wainstein A, et al. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: a clinical study of 12 episodes in 11 patients. Gut. 1994;35:101–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sibai BM, Ramadan MK, Usta I, et al. Maternal morbidity and mortality in 442 pregnancies with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP syndrome) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1000–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90043-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kingham JG. Liver disease in pregnancy. Clinical medicine. 2006;6:34–40. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.6-1-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kallen B. Hyperemesis during pregnancy and delivery outcome: a registry study. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 1987;26:291–302. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(87)90127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duley L. The global impact of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Seminars in perinatology. 2009;33:130–7. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, et al. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2012;87:1202–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, et al. Data resource profile: the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. International journal of epidemiology. 2012;41:1614–24. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knox TA, Olans LB. Liver disease in pregnancy. The New England journal of medicine. 1996;335:569–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;122:1122–31. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williamson C, Geenes V. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;124:120–33. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin JN, Jr, Blake PG, Perry KG, Jr, et al. The natural history of HELLP syndrome: patterns of disease progression and regression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:1500–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)91429-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin JN, Jr, Rinehart BK, May WL, et al. The spectrum of severe preeclampsia: comparative analysis by HELLP syndrome classification. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1373–84. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bacq Y, Riely CA. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: the hepatologist's view. The Gastroenterologist. 1993;1:257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berkson J. Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospital data. Biometrics. 1946;2:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellington SR, Flowers L, Legardy-Williams JK, et al. Recent trends in hepatic diseases during pregnancy in the United States, 2002-2010. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Oct 30; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.10.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallis AB, Saftlas AF, Hsia J, et al. Secular trends in the rates of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension, United States, 1987-2004. American journal of hypertension. 2008;21:521–6. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudra CB, Williams MA. Monthly variation in preeclampsia prevalence: Washington State, 1987-2001. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine. 2005;18:319–24. doi: 10.1080/14767050500275838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira SP, O'Donohue J, Wendon J, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcome in severe pregnancy-related liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:1258–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westbrook RH, Yeoman AD, Joshi D, et al. Outcomes of severe pregnancy-related liver disease: refining the role of transplantation. AJT. 2010;10:2520–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tuffnell DJ, Jankowicz D, Lindow SW, et al. Outcomes of severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia in Yorkshire 1999/2003. BJOG. 2005;112:875–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Habli M, Eftekhari N, Wiebracht E, et al. Long-term maternal and subsequent pregnancy outcomes 5 years after hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:385 e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ropponen A, Sund R, Riikonen S, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy as an indicator of liver and biliary diseases: a population-based study. Hepatology. 2006;43:723–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.21111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider G, Paus TC, Kullak-Ublick GA, et al. Linkage between a new splicing site mutation in the MDR3 alias ABCB4 gene and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Hepatology. 2007;45:150–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.21500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chambers JC, Fusi L, Malik IS, et al. Association of maternal endothelial dysfunction with preeclampsia. JAMA. 2001;285:1607–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, et al. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:974. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.385301.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, et al. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2012;87:151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table. ICD-9 and HICDA codes used to select LDoP subjects