Abstract

Over-expression of the translesion synthesis polymerase (TLS pol) hpol κ in glioblastomas has been linked to a poor patient prognosis; however, the mechanism promoting higher expression in these tumors remains unknown. We determined that activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathway in glioblastoma cells leads to increased hpol κ mRNA and protein levels. We blocked nuclear translocation and DNA binding by the AhR in glioblastoma cells using a small-molecule and observed decreased hpol κ expression. Pharmacological inhibition of tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), the enzyme largely responsible for activating the AhR in glioblastomas, led to a decrease in the endogenous AhR agonist kynurenine (Kyn) and a corresponding decrease in hpol κ protein levels. Importantly, we discovered that inhibiting TDO activity, AhR signaling, or suppressing hpol κ expression with RNA interference led to decreased chromosomal damage in glioblastoma cells. Epistasis assays further supported the idea that TDO activity, activation of AhR signaling and the resulting over-expression of hpol κ function primarily in the same pathway to increase endogenous DNA damage. These findings indicate that up-regulation of hpol κ through glioblastoma-specific TDO activity and activation of AhR signaling likely contributes to the high levels of replication stress and genomic instability observed in these tumors.

Keywords: Aryl hydrocarbon receptor, DNA replication, glioblastoma, kynurenine, polymerase, translesion DNA synthesis

INTRODUCTION

Primary brain tumors arising in glial cells (gliomas) are one of the deadliest forms of cancer, accounting for 28% of all brain tumors and 80% of all malignant central nervous system tumors.1 As such, they represent the most common type of primary brain tumor in adults. With standard-of-care treatment, glioma patients diagnosed with the most malignant form of the disease, glioblastoma (also referred to as glioblastoma multiforme, GBM), have a median survival time of a little over 14 months, and without treatment, the median survival time for GBM patients is only ~4 months.1 The poor prognosis for glioma patients is due to several factors including (i) the location of the tumor, (ii) resistance to post-surgical therapy, as well as heterogeneity inherent to this disease, and (iii) a relative dearth of effective therapeutic options.2 Difficulties in treating gliomas with chemotherapy and radiation are due in part to the fact that these tumors exhibit constitutive activation of replication stress response (RSR) and DNA damage response (DDR).3 Early in the disease, these responses are thought to act as a barrier to tumorigenesis, but persistent replication stress contributes to tumor progression by selecting for mutations, such as mutant p53, that facilitate escape from cell-cycle checkpoint control and promote increased genomic instability.

In response to replications stress, specialized translesion DNA polymerases (TLS pols) are recruited to the fork as part of the DNA damage tolerance pathway.4 The Y-family member hpol κ resolves replication stress and is considered important for the bypass of bulky DNA adducts.5–8 Recently, DNA synthesis by hpol κ has been implicated in the activation of the Chk1 checkpoint pathway and the promotion of cell-cycle arrest.9, 10 In unstressed cells, the loss of hpol κ led to reduced phosphorylation of Chk1 and an increase in γH2AX9, a marker of RSR and DDR activation11. Conversely, separate studies have shown that over-expression of hpol κ can have effects on genomic stability that are just as detrimental as loss of hpol κ function, including reduced replication fork speed, increased γH2AX foci, higher levels of chromosomal damage, and tumorigenesis in immunodeficient mice.12, 13 A 2010 study with a cohort of 104 glioma patients found that increased expression of hpol κ was (i) associated with advanced tumor stage and (ii) correlated with shorter survival time.14 The authors went on to conclude that expression of hpol κ could be used as an independent prognostic factor for evaluating glioma patient outcome.14 From these and other studies, it is readily apparent that the precise regulation of TLS pols, such as hpol κ, is crucial to genome maintenance.

Post-translational modification of the sliding clamp has been the focus of many studies investigating the regulation of TLS pols, and these events clearly play a vital role in coordinating DNA damage tolerance.15–19 There are, however, additional mechanisms that are thought to regulate expression of TLS pols, such as the induction of pol κ expression upon activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR).20 Important studies have revealed that pol κ is critical to cell survival and accurate bypass of DNA adducts produced following exposure to AhR agonists like benzo[a]pyrene.6, 7, 21, 22 Given recent evidence implicating AhR activation in glioma pathology23, we hypothesized that over-expression of hpol κ in glioblastomas might be related to aberrant activation of the AhR pathway observed in these tumors. In the current study, we explored this hypothesis using in vitro approaches in an effort to uncover a previously unrecognized connection between kynurenine (Kyn)-driven activation of AhR signaling and genomic instability.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

All chemicals were molecular biology grade or better. L-kynurenine (Kyn), 3-methylcholanthrene (3-MC), and L-tryptophan (Trp) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The small-molecule inhibitor 680C91 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK) and CH-223191 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell Culture

The glioblastoma-derived cell lines A172, T98G, and U-87-MG were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). The cells were maintained (5% CO2 at 37 ºC) using either Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (A172 cells) or Modified Eagle’s medium (U-87-MG and T98G cells) containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum. A solution of 1% (v/v) antibiotic/antimycotic containing 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to all cell culture media. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was prepared by adjusting the pH of a solution containing 10 mM sodium phosphate dibasic, 2 mM potassium phosphate monobasic, 137 mM NaCl and 2.7 mM KCl to 7.4 (1X PBS). Where indicated, cell lines were treated with 1 μM 3-MC. The addition of DMSO alone served as our control experiment. The final concentration of DMSO was 0.1% (v/v) for all experiments. Cells were treated with agonist or DMSO for 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, or 48 hr prior to being harvested. Cells were scraped, washed with PBS, pelleted by centrifugation (1,000 x g for 5 min), and stored at −20 °C for further analysis. For experiments that examined tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) activity on hpol κ expression/activity, cells were treated with the small-molecule inhibitor of TDO 680C91 (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) alone (10 or 100 μM, as indicated) or 680C91 (10 μM) in combination with exogenous kynurenine (100 μM). The addition of DMSO alone served as our control experiment, with a final concentration of DMSO in each treatment of 1.0%. The cells were harvested by scraping after 24 hr and stored at −20°C for further analysis.

RNA interference

Cells were transfected with targeted siRNA oligonucleotides (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) at a final concentration of 33 nM using Lipofectamine™ (ThermoFisher Scientific, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The siRNA duplexes had the following sense sequences: hpol κ - 5′-GCAAUACAGCCUAUGUCAAGAACTT-3′. Knockdown efficiency was examined using quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) and Western blot analysis at 24, 48, and 72 hr after transfection. For qRT-PCR analysis, RNA was isolated from each pellet using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The isolated RNA was treated with DNase I (Invitrogen) to remove any contaminating DNA and Superscript First Strand Synthesis (Invitrogen) was used to generate cDNA with random primers. The cDNA concentration was then measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and 150 ng/μL stocks were prepared. Finally, real-time PCR was performed in technical triplicate in the presence of SYBR-Green dye (Bio-rad Laboratories) using the following primers: β-Actin forward primer (5′-CTGTGGCATCCACGAAACTA-3′) and reverse (5′-GAGCCAGAGCAGTGATCTCC-3′), hPol κ forward primer (5′-TTTCCTTCATATCTCCTTGGGTC-3′) and reverse (5′-ATA GGCTGTATTGCTCTTCCG-3′), hPol forward primer (5′-TCTACTGGCACAAGTTCGTG-3′) and reverse (5′-GCACTGGTCAGATCTACGTAAG-3′), CYP1A1 forward primer (5′-ATTGAGCACTGTCAGGAGAAG-3′) and reverse (5′-CCAGGAGATAGCAGTTGTGAC-3′). The real-time PCR protocol was performed as follows: a hot start for 2 minutes at 95 °C, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds, then 50 °C for 20 seconds. A melting curve from 50 °C to 95 °C was also performed following the PCR reaction to identify primer pairs that may form dimers. Data was analyzed using the Pffaffl method.24

Immunoblotting

Cell pellets were lysed for 45 min at 4 °C in 40 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) buffer containing 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, and 1% (v/v) TritonX-100 with 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) added. The lysate was centrifuged for 15 min at 13000 x g. The protein concentration of the supernatant was estimated using a Pierce™ bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Samples (10 or 25 μg total protein per sample as indicated) were mixed with Laemmli buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol at a 1:1 ratio, heated for 10 min at 95 °C, and loaded on a 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel. The NHA lysate was obtained from ScienCell (Carlsbad, CA). The separated proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Sigma). After blocking with 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in 1X PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20, the membranes were probed with a hPol κ antibody (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) at a 1:5,000 dilution in PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20, and 0.1% (w/v) BSA. A horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific) was added at a 1:5,000 dilution. The membranes were also probed with antibodies against the DNA damage marker -H2AX (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). After blocking in 5% (w/v) BSA in 1X PBS with 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, primary antibody against -H2AX was added at a 1:1,000 dilution in dilution buffer. Secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific) was then added at a 1:1,000 dilution in dilution buffer. Equal protein loading was verified using a β-actin antibody (Novus Biologicals) at a 1:5,000 dilution in dilution buffer after blocking in 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in 1X PBS with 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20. Secondary antibody was added at a 1:5,000 dilution in dilution buffer (Thermo Scientific). Protein bands were visualized using chemiluminescence (BioRad, Hercules, CA) detection on either the ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) or film. Quantification of the bands was performed using ImageJ software.

Measurement of Kyn secreted into the media by GBM cells

T98G cells were treated with the TDO inhibitor as described above. The media was collected and diluted with an equal volume of 0.2% (v/v) formic acid in water. As an internal standard, 4-nitrophenol (4NP, 1,000 pmoles) was added to each sample prior to processing. Ice cold 0.2% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile was then added to precipitate the proteins. The samples were centrifuged at 15,000 x g at 4 °C for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was collected. The supernatant was centrifuged under vacuum until dry and then re-suspended in 30 μL of 0.1% (v/v) acetic acid in acetonitrile. Samples were separated on a Zorbax Eclipse 5 μm XDB-C18 column (Agilent) heated to 45 °C using an isocratic method. The mobile phase was delivered at a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min. Absorbance at 360 nm was used to monitor elution of Kyn and 4NP from the column. Peak area was quantified and normalized to the internal standard and the concentration of Kyn in each sample was determined using a standard curve. Percent inhibition of TDO activity was calculated by dividing the change in Kyn concentration ([after treatment] – [before treatment]) for the treated samples by the change in concentration observed for the control experiment.

Micronucleation Assays

T98G cells were grown and processed in 8-well Lab-Teks Chamber Slide™ System slides (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cells were treated with 680C91 (10 or 100 μM) and/or CH-223191 (10 μM) for 24 hr. The addition of DMSO alone served as our control experiment, with a final concentration of DMSO in each treatment of 1.0% (v/v). In knockdown experiments, cells were lipofected with 6 pmoles siRNA against hPol κ (see siRNA knockdown protocol above) or a scrambled sequence. 48 hr after lipofection or 24 hr after TDO inhibition, cells were washed and treated with cytochalasin-B (2 μg/mL) (Sigma) for an additional 24 hr before fixation with formaldehyde. Slides were permeabilized in a PBS solution containing 0.2% (v/v) Triton X, 0.01% (w/v) sodium azide, and 100 μg/mL OVA (chicken). Slides were then stained with mouse anti-a tubulin (Sigma) at a 1:500 dilution in the permeabilization solution followed by anti-mouse secondary antibody at a 1:100 dilution in the permeabilization solution and mounted in Vectashield with 0.1 μg/mL DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were obtained at 60X magnification and micronuclei scoring was blinded according to established criteria. Experiments were repeated in biological replicate (n = 3 or 4) and >50 cells were scored per condition per replicate. The mean and standard deviation of each condition was calculated and a Student’s t-test was applied.

RESULTS

Glioblastoma-derived cell lines over-express hpol κ and exhibit DNA damage response activation

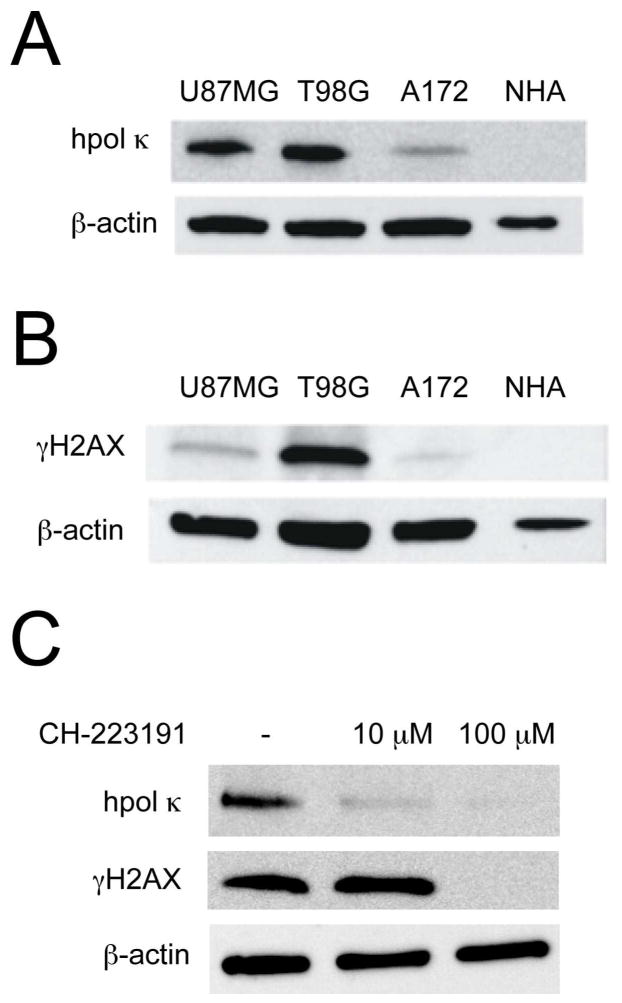

To ascertain the relative expression of hpol κ in GBM-derived cell lines, we performed Western blot analysis on lysates from normal human astrocytes and three GBM-derived cell lines: A172, U-87-MG, and T98G (Fig. 1A). All three GBM-derived cell lines expressed hpol κ, and T98G cells showed the highest level of expression for the TLS pol. Expression of hpol κ in NHAs was below the limit of detection when 10 μg of total protein was loaded onto the gel. A comparison of the three GBM samples revealed that hpol κ expression in U-87-MG cells was ~90% of that observed in T98G cells, while hpol κ expression in A172 cells was ~40% of that observed in the other two tumor-derived cell lines. As a measure of DDR activation in these cell lines, we probed for expression of γH2AX (Fig. 1B). The level of γH2AX in the three GBM cell lines revealed that, like hpol κ, T98G cells exhibited the highest level of γH2AX, the U-87-MG cell line had an intermediate level of γH2AX, and A172 cells had the lowest amount of γH2AX for the three GBM cell lines tested. Again, γH2AX was not detected in NHAs under these conditions. These results confirm that, similar to patient samples, GBM-derived cell lines expressed higher levels of hpol κ than NHAs and that constitutive activation of the DDR occurred in GBM cells, as reported by others3 and evidenced by relatively high γH2AX levels.

Figure 1.

High levels of hpol κ and γH2AX expression in glioblastoma cell lines is modulated by inhibition of AhR signaling. A. The relative expression of hpol κ was examined by immunoblotting using total cell lysate from three glioblastoma-derived cell lines (T98G, U-87-MG, and A172), as well as normal human astrocytes (NHAs). B. Expression of the DNA damage response protein γH2AX was determined by immunoblotting. C. Expression of hpol κ and γH2AX in T98G glioblastoma cells treated with the AhR inhibitor CH-223191 (10 μM and 100 μM, 24 hrs) were determined by immunoblotting. Expression of both hpol κ and γH2AX decrease in cells treated with 100 μM CH-223191.

We then determined whether direct inhibition of the AhR signaling pathway modulated hpol κ expression levels. We used the small-molecule CH-223191 to block AhR action in glioblastoma cells and then probed for changes in hpol κ expression, as well as γH2AX formation. We observed a decrease in hpol κ expression following exposure of T98G cells to the AhR inhibitor CH-223191 (Fig. 1C). Likewise, we observed a decrease in γH2AX but only at the higher concentration of CH-223191 (Fig. 1C). The reduction in hpol κ expression in response to treatment with CH-223191 supported a role for the AhR in the aberrant stimulation of TLS in glioblastoma cells.

Treatment with the AhR agonist 3-MC increases expression of hpol κ

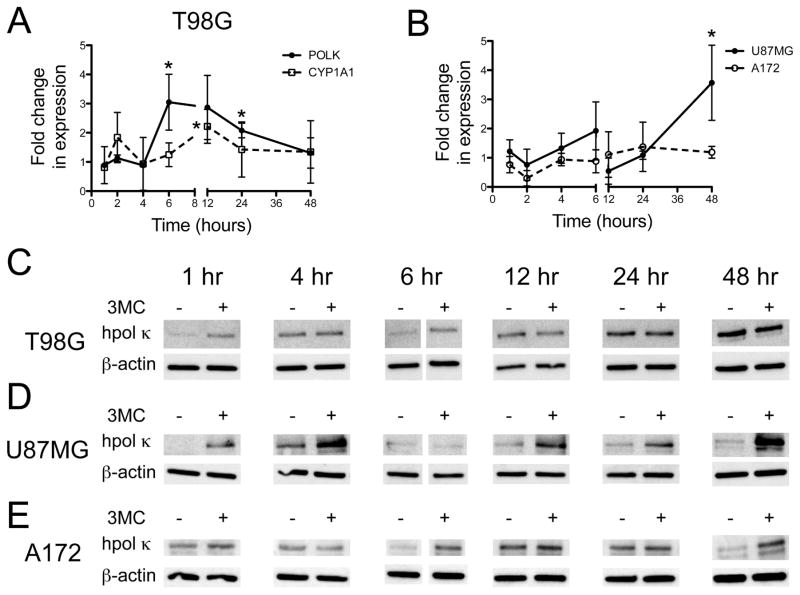

We next examined whether treating GBM cells with the AhR agonist 3-MC alters the expression of the POLK gene. The T98G GBM-derived cell lines were exposed to 3-MC (1 μM) for up to 48 hr and changes in hpol κ transcript levels were measured by real time PCR. As a positive control, we monitored changes in expression of the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP1A1, a known responder to AhR activation. The resulting qRT-PCR analysis revealed different transcriptional responses for the two genes. The expression of POLK increased 3-fold relative to DMSO-treated cells after six hr exposure to 3-MC and then gradually decreased to near basal levels at 48 hr (Fig. 2A). The CYP1A1 transcript increased 2-fold relative to control cells at four hr and then again at 12 hr before decreased back to near basal levels at 48 hr (Fig. 2A). We also measured 3-MC-induced changes in POLK mRNA in U-87-MG and A172 glioblastoma cells. Compared to T98G cells, more modest changes in POLK transcript levels were observed in the other two GBM cell lines (Fig. 2B). Monitoring changes in protein by immunoblotting revealed an increase in hpol κ expression as early as one hour after treatment with 3-MC in T98G and U87MG cells, with A172 cells displaying a noticeable increase in hpol κ expression at 6 hrs (Fig. 2C–E). The hpol κ protein levels returned to that of the control experiment by 12 hrs in both T98G and A172 cells (Fig. 2C and E). The A172 cells then exhibited an increase in hpol κ expression at 48 hrs, while protein levels remained near that of the control in T98G cells treated for 48 hrs with 3-MC. For U-87-MG cells, hpol κ protein levels increased early after exposure to 3-MC, returned to basal levels at 6 hrs, and then showed an increase from 12 to 48 hrs (Fig. 2D). The changes in hpol κ expression were not terribly robust following treatment with 3-MC. This is most likely due to the fact that exogenous 3-MC must compete with endogenous Kyn for the AhR in glioblastoma cells. However, the combined immunoblotting and qRT-PCR results were consistent with a model where activation of the AhR caused in an increase in the number of hpol κ transcripts and protein in glioblastoma cells.

Figure 2.

Expression of hpol κ changes in glioblastoma cells treated with the AhR agonist 3-MC. A. The expression of the POLK and CYP1A1 genes in T98G glioblastoma cells treated with 3-MC (1 μM) was measured relative to DMSO control over a period of 48 hrs using qRT-PCR. The values shown represent the mean ± s.d. (n = 3). A two-tailed Student’s t-test revealed that statistically significant changes in expression occurred at 6 hrs (P = 0.031) and 24 hrs (P = 0.039) for POLK and at 12 hrs for CYP1A1 (P = 0.013). B. The expression of POLK in U-87-MG and A172 glioblastoma cells treated with 3-MC (1 μM) was measured relative to DMSO control over a period of 48 hrs using qRT-PCR. The values shown represent the mean ± s.d. (n = 3). A two-tailed Student’s t-test revealed that statistically significant changes in POLK expression occurred at 48 hrs (P = 0.038) in U-87-MG cells. C–E. Immunoblotting reveals changes in hpol κ expression in all three glioblastoma cell lines following treatment with 3-MC (1 μM).

Pharmacological inhibition of the Kyn signaling pathway reduces hpol κ expression and γH2AX formation in glioblastoma cells

Recent studies have implicated aberrant activation of the AhR by the tryptophan catabolite kynurenine (Kyn) in glioma progression.23 Catabolism of tryptophan (Trp) to the AhR agonist Kyn drives several features related to brain tumor malignancy (e.g. suppression of anti-tumor immune response, tumor cell survival and motility). We tested the hypothesis that AhR activation through the Kyn pathway leads to over-expression of hpol κ in GBM cells by treating GBM-derived cells with an inhibitor of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), the enzyme that catalyzes the rate-limiting step in Kyn formation.

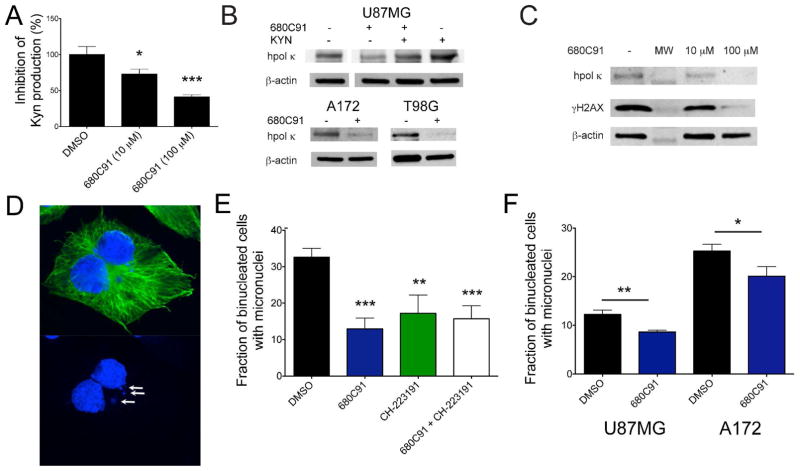

We first measured the amount of Kyn in the media of T98G cells treated with either DMSO or the TDO inhibitor 680C91 to be certain that our experimental conditions caused a reduction in the amount of endogenous AhR ligand similar to what was reported previously in U-87-MG cells.23 The amount of Kyn in each dish was measured before and after treatment to normalize for baseline Kyn production in each sample. Media was collected 24 hrs after plating the cells (i.e. before treatment) and replaced with fresh media containing either DMSO or 680C91 (10 μM and 100 μM). The cells were cultured another 24 hrs and the medium was collected again. The change in Kyn from the baseline concentration was calculated for each sample to determine how much the Kyn concentration changed as the cells proliferated in the presence of either DMSO or 680C91. As expected, the addition of 680C91 caused a dose-dependent reduction in Kyn production (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Modulation of Kyn signaling alters hpol κ expression and DNA damage levels in glioblastoma cells. A. Kyn production was measured in glioblastoma cells treated with the TDO inhibitor 680C91 (10 μM and 100 μM, 24 hrs). The Kyn concentration in the media was measured before and after treatment with 680C91 to calculate the percent inhibition of TDO activity. Values reported represent the mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3). A statistically significant decrease in TDO activity was observed at both concentrations of 680C91 (10 μM 680C91, P = 0.023; 100 μM 680C91, P = 0.0009). B. Immunoblotting of lysates from U-87-MG cells treated with DMSO, 680C91 (10 μM, 24 hrs), 680C91 (10 μM) + Kyn (100 μM), or Kyn (100 μM) alone reveals that inhibition of TDO activity decreases hpol κ levels. Adding Kyn to the cell culture conditions abrogates the effect of 680C91 and adding excess Kyn (100 μM) further increases expression of hpol κ. Similar to U-87-MG cells, treating either T98G or A172 cells with 680C91 (10 μM) leads to a decrease in hpol κ expression. C. Treating T98G cells with increasing concentrations of 680C91 leads to a dose-dependent reduction in both hpol κ and γH2AX expression. D. Micronuclei (MN) were quantified in glioblastoma cells using immunofluorescence against α-tubulin (green) and with DAPI (blue) staining. A representative binucleated cell containing MN (white arrows) is shown. E. The percentage of binucleated cells containing MN was quantified for T98G cells treated with DMSO (33.6 ± 1.2 %), 10 μM 680C91 (12.9 ± 1.5 %, P = <0.0001 when compared to DMSO), 10 μM CH-223191 (17.2 ± 2.5%, P = 0.0015 when compared to DMSO), and 10 μM 680C91 + 10 μM CH-223191 (15.7 ± 1.8%, P = 0.0002 when compared to DMSO). The values reported represent the mean ± s.e.m for n = 4, >50 binucleated cells were scored for each biological replicate. F. The percentage of binucleated cells containing MN was quantified for U-87-MG cells treated with DMSO (12.3 ± 0.5 %), 10 μM 680C91 (8.7 ± 0.2 %, P = 0.0029 when compared to DMSO), and for A172 cells treated with DMSO (25.3 ± 0.8 %), 10 μM 680C91 (20.1 ± 1.1 %, P = 0.022 when compared to DMSO); The values reported represent the mean ± s.e.m for n = 3, >50 binucleated cells were scored for each biological replicate. Asterisks in all panels represent P values calculated using an unpaired Student’s t-test for treatments relative to control.

Next, the effect of 680C91 on hpol κ expression was tested. As expected, treatment with 680C91 (10 μM) reduces hpol κ expression in all three glioblastoma cell lines (Fig. 3B). Kyn has been shown to preferentially accumulate in the mammalian brain through the action of large neutral amino acid transporters (LATs).25–27 High-expression of LAT-1 has been observed in infiltrating glioma tissue from glioma patients.28 Therefore, we attempted to restore hpol κ expression by adding exogenous Kyn to the media. Previous studies measured Kyn concentrations from the media glioblastoma cells in the range of 5–60 μM, and a maximal response for a dioxin-responsive luciferase reporter system when glioblastoma cells were treated with 100 μM Kyn.23 Adding exogenous Kyn (100 μM) abrogated the effect of 680C91 by restoring hpol κ expression back to the levels observed in DMSO treated cells. Furthermore, addition of exogenous Kyn alone led to an increase in hpol κ expression similar to what was observed in glioblastoma cells treated with 3-MC. Interestingly, we also observed a dose-dependent decrease in γH2AX formation following treatment with the TDO inhibitor (Fig. 3C), suggestive of less ongoing DNA damage/replication stress. These results are consistent with the notion that AhR activation through the Kyn pathway contributes to over-expression of the TLS enzyme hpol κ and activation of the DDR/RSR in GBM-derived cells.

Inhibition of either Kyn signaling or AhR activation reduces chromosomal damage in glioblastoma cells

The decreases in γH2AX we observed in experiments blocking AhR signaling indicated that there was less ongoing DNA damage. Given the fact that over-expression of hpol κ has been shown elsewhere to promote genomic instability by several different measures, we wanted to determine if suppressing hpol κ altered DNA damage levels in GBM-derived cells. As a more direct measurement of DNA damage, we assessed the formation of micronuclei (MN) in cells treated with AhR-modulating agents (Fig. 3D).

First, we measured the number of binucleated cells with MN formation in T98G cells treated with either the TDO inhibitor 680C91, the AhR inhibitor CH-223191, or a combination of the two inhibitors (Fig. 3E). Addition of either inhibitor significantly decreased MN formation in binucleated cells. Combining the two inhibitors did not further reduce the percentage of MN positive cells. The lack of an additive effect on MN formation in the combined treatment is consistent with the notion that TDO activity influences genomic instability largely through a pathway involving the AhR. Similar to T98G cells, treating U-87-MG and A172 cells with the TDO inhibitor resulted in decreased MN formation (Fig. 3F). The T98G cell line had the highest level of endogenous MN (32.6 ± 1.2%) followed by A172 cells (25.3 ± 0.8%), and U-87-MG cells possessed the lowest number of endogenous MN (12.3 ± 0.5%). The reduction in damage following treatment with 680C91 was most pronounced for T98G cells where MN formation decreased nearly 3-fold relative to the DMSO control (from 32.6 % ± 1.2% to 12.9 ± 1.5%, P = <0.0001). In A172 cells, MN formation was reduced ~20% relative to control (P = 0.022) following treatment with 680C91, while U-87-MG cells exhibited an approximate 30% decrease in MN relative to control (12.3 ± 0.5% for DMSO versus 8.7 ± 0.2% for 680C91 treated cells; P = 0.0029). These results support a model in which Kyn signaling has an important role in determining the level of endogenous DNA damage in gliomas. Such a scenario is consistent with the model proposed by others relating TDO-related activation of AhR with tumor cell survival/motility and evasion of the anti-tumor immune response in glioblastomas.23

TDO signaling, AhR activation, and hpol κ expression act in a single pathway to increase genomic instability in glioblastoma cells

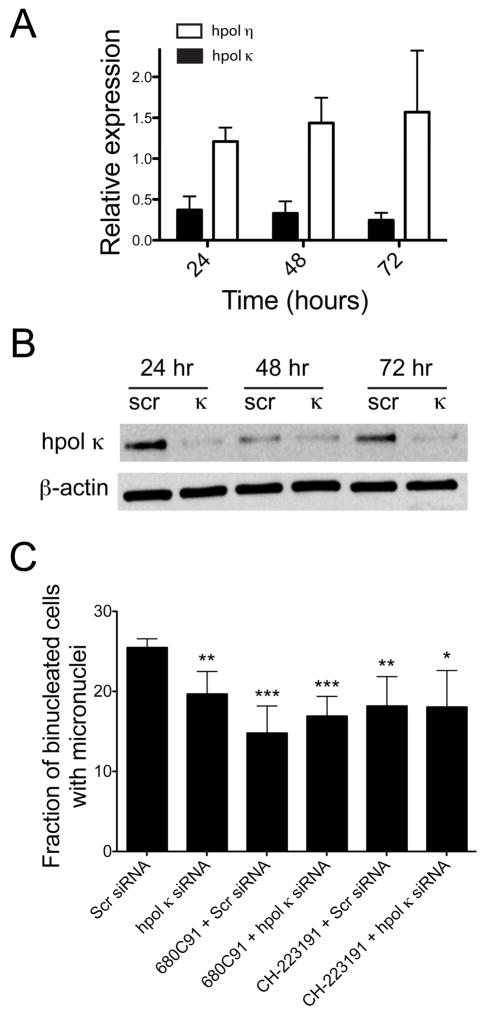

Next, we wanted to test whether knock-down of hpol κ expression alone had any effect on MN formation in glioblastoma cells. Transient siRNA-mediated knock-down of hpol κ expression was confirmed in T98G cells by qRT-PCR and western blotting (Fig. 4A and 4B). Suppression of hpol κ transcript and protein levels was observed over a 72 hr period. We then compared MN formation in cells treated with siRNA targeting hpol κ to control cells treated with scrambled siRNA duplexes. There was an approximate 23% decrease in MN in glioblastoma cells that had hpol κ knocked down relative to the cells treated with a scrambled control siRNA duplex (Fig. 4C), reminiscent of the decrease in MN observed in cells treated with either 680C91 or CH-223191.

Figure 4.

Transient knock-down of hpol κ reduces MN formation and epistasis assays reveal that TDO, AhR, and hpol κ function together to effect genomic instability in glioblastoma cells. A. Transcript levels for mRNA encoding either hpol η (white bars) or hpol κ (black bars) were quantified in cells treated with siRNA targeting hpol κ for knock-down and compared to cells treated with scrambled (scr, control) siRNA. The relative expression of each transcript was measured at 24, 48, and 72 hr (n = 2). The expression of hpol κ decreases by ~60-80% over the 72 hr time period, while hpol η expression does not change. B. Knock-down of hpol κ was confirmed by immunoblotting. C. The percentage of MN in cells treated with either scr or hpol κ siRNA alone or in combination with 680C91 (10 μM) or CH-223191 (10 μM). MN formation decreases from 25.5 ± 0.5 % for scr siRNA to 19.7 ± 0.5 % hpol κ (P = 0.0087). Combining 680C91 with scr and hpol κ siRNA results in MN formation of 14.8 ± 1.7 % for scr siRNA (P = 0.0010 compared to scr siRNA alone) to 16.9 ± 1.2 % hpol κ (P = 0.0007 compared to scr siRNA alone), respectively. Combining CH-223191 with scr and hpol κ siRNA results in MN formation of 18.2 ± 1.8 % for scr siRNA (P = 0.0090 compared to scr siRNA alone) to 18.0 ± 2.3 % hpol κ (P = 0.019 compared to scr siRNA alone), respectively. The values reported represent the mean ± s.e.m for n = 4, >50 binucleated cells were scored for each biological replicate.

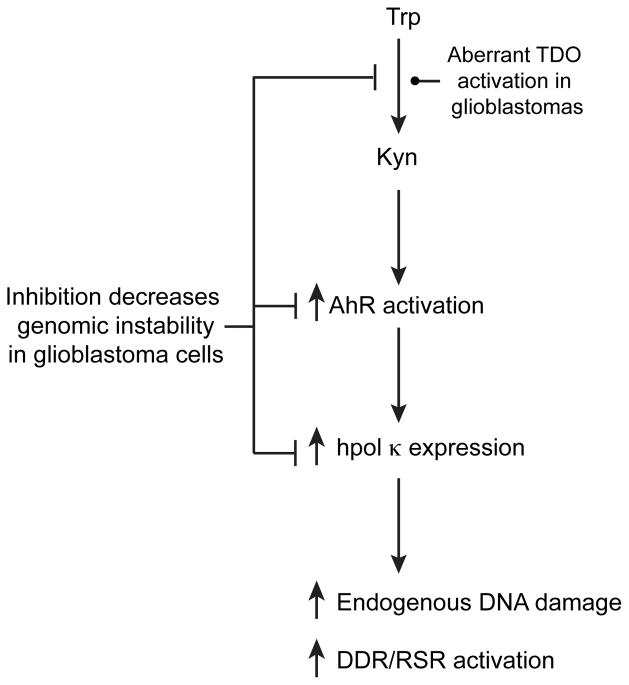

We tested whether TDO activity, AhR activation, and hpol κ expression were acting together to influence endogenous DNA damage levels in glioblastoma cells using epistasis-type experiments that combined knock-down of hpol κ with pharmacological inhibition of either TDO activity or AhR activation. Knock-down of hpol κ with either TDO inhibition (10 μM 680C91) or AhR inhibition (10 μM CH-223191) failed to produce an additive effect on MN formation (Fig. 4C). These results again point to all three factors (TDO, AhR, and hpol κ) functioning in a single pathway to impact MN formation in glioblastoma cells (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Kyn signaling through AhR activation and increased hpol κ expression leads to constitutive DDR/RSR activation and higher levels of endogenous DNA damage. A model depicting the relationship between aberrant Kyn signaling, AhR activation, and over-expression of hpol κ is shown. Modulation at any point along this pathway alters endogenous DNA damage levels in glioblastoma cells.

DISCUSSION

Malignant gliomas are an especially deadly form of cancer, and patients with this disease usually face a grim prognosis. Ongoing DNA damage through constitutive activation of replication stress contributes to glioblastoma progression and resistance to genotoxic anti-cancer drugs.3 The protective effect of DDR and RSR activation in low-grade astrocytomas is thought to become deleterious at later stages of the disease once selection of mutant tumor cells that have escaped cell cycle checkpoint/senescence mechanisms (e.g. p53-mutant clones) has occurred. A retrospective analysis of TLS pol expression in glioma samples further supports such a model, as over-expression of hpol κ was found to be an independent prognostic indicator of poor outcomes for patients with malignant gliomas.14 In that study, the fraction of patients staining positive for hpol κ increased from ~50% for stage I and II gliomas to ~80-90% of hpol κ-positive for patients with stage III or IV gliomas, but the factors driving over-expression of hpol κ in glioblastomas have remained poorly defined.

The objective of the current study was to elucidate molecular mechanisms contributing to mis-regulation of hpol κ in glioblastomas. Previous work has established that expression of POLK in mammals is stimulated following exposure to AhR agonists, such as 3-MC and B[a]P.20, 22, 29 Recent studies have highlighted a role for aberrant activation of AhR signaling in both malignant progression and evasion of the immune response.23, 30 Moreover, TDO activity is known to stimulate proliferation of glioblastoma cells, based on Ki67 staining.23 It is, therefore, not unreasonable to propose that these processes might be functioning together to affect primary brain tumors. The results of our study support the idea that there is a direct connection between AhR activation, hpol κ expression, and ongoing DNA damage, as down-regulation of TDO-Kyn-AhR signaling leads to a reduction in chromosomal damage. Linking these three factors to glioma pathology provides a new framework for understanding how these tumors progress and respond to treatments.

Others have reported the effect of hpol κ over-expression on genome stability and replication fork progression.12, 13 It is clear from those previous studies that expression of hpol κ can be a double-edged sword. Deficiencies in hpol κ expression can lead to failed bypass of DNA adducts and/or failure to activate Chk1 signaling with subsequent cell cycle arrest, while over-expression can interfere with replication fork dynamics and increase genomic instability.9, 12, 13 Based on our results, reducing the amount of hpol κ expressed in glioblastoma cells through inhibition of TDO-Kyn-AhR signaling leads to a decrease in chromosomal damage. It is tempting to speculate that limiting the amount of DNA damage in gliomas contributed in part to the slower tumor growth observed previously in a TDO-deficient xenograft model of glioblastoma.23 Whether hpol κ is important to the reduced tumor growth in these animals is unknown, but our finding that reducing hpol κ expression leads to less MN formation in glioblastoma cells is certainly consistent with such a scenario.

TDO is normally expressed in the liver and neurons, but the enzyme has been reported to be expressed at high levels in multiple types of cancer.23 Furthermore, animal models of Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases implicate abnormal TDO activity with neurodegeneration.31, 32 Still, it remains unclear what drives aberrant TDO expression in glioblastomas. A recent study revealed a negative correlation between expression of FKBP52 (an immunophilin with peptidylprolyl isomerase activity involved in the steroid receptor/heat shock protein 90 heterocomplex) and TDO in tumors of glial origin.33 The same study showed that increasing endogenous glucocorticoid signaling reduces TDO expression in glioblastoma cells.33 Similarly, they found that treating glioblastoma cells with the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone (DEX) also reduced TDO expression and activity.33 Interestingly, DEX has been shown to act as a radiosensitizer in astrocytoma cells.34 However, an earlier study found that DEX upregulated alkylguanine transferase (AGT, also called methylguanine methyl transferase, MGMT) in HeLa cells, which led to increased DNA repair.35 It remains to be seen if a similar effect is observed in glioblastoma cells where AGT plays an important role in determining patient response to temozolomide (TMZ) and other DNA alkylating agents.

Modulation of the interplay between Kyn signaling and DDR/RSR in gliomas could be leveraged to help improve patient response to chemotherapy and/or slow progression of the disease. Constitutive activation of cellular responses involved in removing/bypassing DNA damage is clearly a barrier to successful treatment with genotoxic agents, such as TMZ, and improved outcomes have been realized by combining DNA damaging agents with inhibitors of the repair proteins, such as AGT.36–38 The exact role of hpol κ in resistance to TMZ has not been determined, but there is some indication that it is relevant to the bypass of alkylated DNA.39, 40 As such, decreasing hpol κ activity, either directly or indirectly through modulation of Kyn signaling, could improve the efficacy of drugs like TMZ. Additionally, an intriguing possibility is that over-expression of hpol κ could be further enriched in the tumor-initiating stem-like population of cells within gliomas similar to what has been observed for hpol η in ovarian cancer stem cells.41

CONCLUSIONS

The results described herein help establish a link between the aberrant activation of Kyn signaling and AhR-induced activation of TLS in glioblastomas. We find that modulation at any point in the TDO-AhR-hpol κ pathway alters the amount of endogenous DNA damage observed in glioblastoma cells, and it seems likely that this feature may contribute to tumor properties observed in vivo. Further exploration of TDO-AhR-hpol κ activation and the relationship between Kyn-signaling and DNA damage in glioblastomas will help improve our understanding of how tryptophan metabolism affects brain tumor biology, and may eventually allow us to propose new and potentially more effective routes to improving treatments for patients with this deadly disease.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01CA185893 (R.L.E.) with additional support from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Translational Research Institute (CTSA Grant Award UL1TR000039), the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship DGE 1452779 (J.H.H.) and the UAMS College of Medicine.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AhR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

- Kyn

kynurenine

- TDO

tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase

- TLS

translesion DNA synthesis

- TMZ

temozolomide

- Trp

tryptophan

References

- 1.Ostrum QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, Rouse C, Chen Y, Dowling J, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan J. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2007–2011. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:iv1–63. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furnari FB, Fenton T, Bachoo RM, Mukasa A, Stommel JM, Stegh A, Hahn WC, Ligon KL, Louis DN, Brennan C, Chin L, DePinho RA, Cavenee WK. Malignant astrocytic glioma: genetics, biology, and paths to treatment. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2683–2710. doi: 10.1101/gad.1596707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartkova J, Hamerlik P, Stockhausen MT, Ehrmann J, Hlobilkova A, Laursen H, Kalita O, Kolar Z, Poulsen HS, Broholm H, Lukas J, Bartek J. Replication stress and oxidative damage contribute to aberrant constitutive activation of DNA damage signalling in human gliomas. Oncogene. 2010;29:5095–5102. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sale JE, Lehmann AR, Woodgate R. Y-family DNA polymerases and their role in tolerance of cellular DNA damage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:141–152. doi: 10.1038/nrm3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avkin S, Goldsmith M, Velasco-Miguel S, Geacintov N, Friedberg EC, Livneh Z. Quantitative analysis of translesion DNA synthesis across a benzo[a]pyrene-guanine adduct in mammalian cells: the role of DNA polymerase kappa. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53298–53305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409155200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bi X, Slater DM, Ohmori H, Vaziri C. DNA polymerase kappa is specifically required for recovery from the benzo[a]pyrene-dihydrodiol epoxide (BPDE)-induced S-phase checkpoint. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22343–22355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi JY, Angel KC, Guengerich FP. Translesion synthesis across bulky N2-alkyl guanine DNA adducts by human DNA polymerase kappa. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21062–21072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jia L, Geacintov NE, Broyde S. The N-clasp of human DNA polymerase kappa promotes blockage or error-free bypass of adenine- or guanine-benzo[a]pyrenyl lesions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6571–6584. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Betous R, Pillaire MJ, Pierini L, van der Laan S, Recolin B, Ohl-Seguy E, Guo C, Niimi N, Gruz P, Nohmi T, Friedberg E, Cazaux C, Maiorano D, Hoffmann JS. DNA polymerase kappa-dependent DNA synthesis at stalled replication forks is important for CHK1 activation. EMBO J. 2013;32:2172–2185. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maiorano D, Hoffmann JS. Pol kappa in replication checkpoint. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:3713–3714. doi: 10.4161/cc.26976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirbu BM, Couch FB, Feigerle JT, Bhaskara S, Hiebert SW, Cortez D. Analysis of protein dynamics at active, stalled, and collapsed replication forks. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1320–1327. doi: 10.1101/gad.2053211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bavoux C, Leopoldino AM, Bergoglio V, JOW, Ogi T, Bieth A, Judde JG, Pena SD, Poupon MF, Helleday T, Tagawa M, Machado C, Hoffmann JS, Cazaux C. Up-regulation of the error-prone DNA polymerase promotes pleiotropic genetic alterations and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:325–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones MJ, Colnaghi L, Huang TT. Dysregulation of DNA polymerase kappa recruitment to replication forks results in genomic instability. EMBO J. 2012;31:908–918. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Wu W, Wang HW, Wang S, Chen Y, Zhang X, Yang J, Zhao S, Ding HF, Lu D. Analysis of specialized DNA polymerases expression in human gliomas: association with prognostic significance. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:679–686. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bienko M, Green CM, Crosetto N, Rudolf F, Zapart G, Coull B, Kannouche P, Wider G, Peter M, Lehmann AR, Hofmann K, Dikic I. Ubiquitin-binding domains in Y-family polymerases regulate translesion synthesis. Science. 2005;310:1821–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.1120615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bienko M, Green CM, Sabbioneda S, Crosetto N, Matic I, Hibbert RG, Begovic T, Niimi A, Mann M, Lehmann AR, Dikic I. Regulation of translesion synthesis DNA polymerase eta by monoubiquitination. Molecular Cell. 2010;37:396–407. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bomar MG, D’Souza S, Bienko M, Dikic I, Walker GC, Zhou P. Unconventional ubiquitin recognition by the ubiquitin-binding motif within the Y family DNA polymerases iota and Rev1. Molecular Cell. 2010;37:408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo C, Tang TS, Bienko M, Dikic I, Friedberg EC. Requirements for the interaction of mouse Pol kappa with ubiquitin and its biological significance. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4658–4664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo C, Tang TS, Bienko M, Parker JL, Bielen AB, Sonoda E, Takeda S, Ulrich HD, Dikic I, Friedberg EC. Ubiquitin-binding motifs in REV1 protein are required for its role in the tolerance of DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8892–8900. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01118-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogi T, Mimura J, Hikida M, Fujimoto H, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Ohmori H. Expression of human and mouse genes encoding polkappa: testis-specific developmental regulation and AhR-dependent inducible transcription. Genes Cells. 2001;6:943–953. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bi X, Barkley LR, Slater DM, Tateishi S, Yamaizumi M, Ohmori H, Vaziri C. Rad18 regulates DNA polymerase kappa and is required for recovery from S-phase checkpoint-mediated arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3527–3540. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3527-3540.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogi T, Shinkai Y, Tanaka K, Ohmori H. Pol kappa protects mammalian cells against the lethal and mutagenic effects of benzo[a]pyrene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15548–15553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222377899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Opitz CA, Litzenburger UM, Sahm F, Ott M, Tritschler I, Trump S, Schumacher T, Jestaedt L, Schrenk D, Weller M, Jugold M, Guillemin GJ, Miller CL, Lutz C, Radlwimmer B, Lehmann I, von Deimling A, Wick W, Platten M. An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature. 2011;478:197–203. doi: 10.1038/nature10491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sekine A, Okamoto M, Kanatani Y, Sano M, Shibata K, Fukuwatari T. Amino acids inhibit kynurenic acid formation via suppression of kynurenine uptake or kynurenic acid synthesis in rat brain in vitro. SpringerPlus. 2015;4 doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-0826-9. eCollection 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Speciale C, Hares K, Schwarcz R, Brookes N. High-affinity uptake of L-kynurenine by a Na+-independent transporter of neutral amino acids in astrocytes. J Neuroscience. 1989;9:2066–2072. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-06-02066.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Speciale C, Schwarcz R. Uptake of kynurenine into rat brain slices. J Neurochem. 1990;54:156–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb13296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nawashiro H, Otani N, Uozumi Y, Ooigawa H, Toyooka T, Suzuki T, Katoh H, Tsuzuki N, Ohnuki A, Shima K, Shinomiya N, Matsuo H, Kanai Y. High expression of L-type amino acid transporter 1 in infiltrating glioma cells. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2005;22:89–91. doi: 10.1007/s10014-005-0188-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brauze DRAA. The effect of aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands on the expression of polymerase (DNA directed) kappa (Pol k), polymerase RNA II (DNA directed) polypeptide A2 (PolR2a), CYP1B1 and CYP1A1 genes in rat liver. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012;34:819–825. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams S, Braidy N, Bessede A, Brew BJ, Grant R, Teo C, Guillemin GJ. The kynurenine pathway in brain tumor pathogenesis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5649–5657. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campesan S, Green EW, Breda C, Sathyasaikumar KV, Muchowski PJ, Schwarcz R, Kyriacou CP, Giorgini F. The kynurenine pathway modulates neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of Huntington’s disease. Curr Biol. 2011;21:961–966. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Groot AT, Zhu W, Vásquez-Manrique RP, Seinstra RI, Dettmer K, Michels H, Farina F, Krijnen J, Melki R, Buijsman RC, Ruiz Silva M, Thijssen KL, Kema IP, Neri C, Oefner PJ, Nollen EA. Delaying aging and the aging-associated decline in protein homeostasis by inhibition of tryptophan degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14912–14917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203083109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ott M, Litzenburger UM, Rauschenbach KJ, Bunse L, Ochs K, Sahm F, Pusch S, Opitz C, Blaes J, von Deimling A, Wick W, Platten M. Suppression of TDO-mediated tryptophan catabolism in glioblastoma cells by a steroid-responsive FKBP52-dependent pathway. Glia. 2015;63:78–90. doi: 10.1002/glia.22734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortega-Martínez S. Dexamethasone acts as a radiosensitizer in three astrocytoma cell lines via oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2015;5:388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grombacher T, Mitra S, Kaina B. Induction of the alkyltransferase (MGMT) gene by DNA damaging agents and the glucocorticoid dexamethasone and comparison with the response of base excision repair genes. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:2329–2336. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.11.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quinn JA, Desjardins A, Weingart J, Brem H, Dolan ME, Delaney SM, Vredenburgh J, Rich J, Friedman AH, Reardon DA, Sampson JH, Pegg AE, Moschel RC, Birch R, McLendon RE, Provenzale JM, Gururangan S, Dancey JE, Maxwell J, Tourt-Uhlig S, Herndon JE, 2nd, Bigner DD, Friedman HS. Phase I trial of temozolomide plus O6-benzylguanine for patients with recurrent or progressive malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7178–7187. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinn JA, Jiang SX, Reardon DA, Desjardins A, Vredenburgh JJ, Rich JN, Gururangan S, Friedman AH, Bigner DD, Sampson JH, McLendon RE, Herndon JE, 2nd, Walker A, Friedman HS. Phase II trial of temozolomide plus O6-benzylguanine in adults with recurrent, temozolomide-resistant malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1262–1267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinn JA, Pluda J, Dolan ME, Delaney S, Kaplan R, Rich JN, Friedman AH, Reardon DA, Sampson JH, Colvin OM, Haglund MM, Pegg AE, Moschel RC, McLendon RE, Provenzale JM, Gururangan S, Tourt-Uhlig S, Herndon JE, 2nd, Bigner DD, Friedman HS. Phase II trial of carmustine plus O6-benzylguanine for patients with nitrosourea-resistant recurrent or progressive malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2277–2283. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin JR, Zeman MK, Chen JY, Yee MC, Cimprich KA. SHPRH and HLTF Act in a Damage-Specific Manner to Coordinate Different Forms of Postreplication Repair and Prevent Mutagenesis. Molecular Cell. 2011;42:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lupari E, Ventura I, Marcon F, Aquilina G, Dogliotti E, Fortini P. Pol kappa partially rescues MMR-dependent cytotoxicity of O6-methylguanine. DNA Repair. 2012;11:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srivastava AK, Han C, Zhao R, Cui T, Dai Y, Mao C, Zhao W, Zhang X, Yu J, Wang QE. Enhanced expression of DNA polymerase eta contributes to cisplatin resistance of ovarian cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:4411–4416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421365112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]