Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate preoperative anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels in women with endometrioma or other benign ovarian cysts and differences of AMH changes according to various characteristics.

Methods

Ninety-seven patients aged 20 to 39 years who underwent surgery for benign ovarian cyst were enrolled retrospectively. Of these, 65 patients were diagnosed as endometriomas, and 32 had other benign cysts. Serum AMH, mean, maximum, and total diameter of ovarian cysts were measured. The AMH levels were compared according to pathology (endometrioma vs. other benign cyst), size of ovarian cyst, age-matched AMH quartile percentile and characteristics of endometrioma.

Results

Preoperative serum AMH level was significantly lower in endometrioma group than other benign cyst group (4.12 ± 2.42 ng/mL vs. 6.02 ± 2.29 ng/mL, P < 0.001). Serum AMH level was significantly lower in endometrioma group, especially in patients aged 30 to 39 years. Dividing to age-matched AMH quartile percentile, there were significantly fewer patients with AMH level ≥ 75 percentile in endometrioma group (24.6% vs. 50.0%, P = 0.035). Among 4 subgroups of endometrioma, patients with AMH level ≥ 75 percentile were significantly decreased in multiple bilateral endometrioma group. Mean and total diameter of cysts were negatively correlated with preoperative serum AMH level in other benign cyst group.

Conclusion

We suggest that preoperative AMH level measurement might be considered in women with endometrioma, especially in 30 to 39 years old, multiple bilateral type, or big-sized other benign ovarian cyst to assess the diminished ovarian reserve.

Keywords: Anti-Müllerian hormone, Endometriosis, Ovarian cysts, Ovarian reserve

Introduction

Ovarian masses are uncertain of their etiology, and making a discrimination between benign masses and malignant masses is difficult. Several studies demonstrate the advantage of using cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) and risk of malignancy index (RMI).1,2 Benign ovarian cysts such as endometrioma, teratoma, serous or mucinous cystadenoma are frequently seen during reproductive age. Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial tissue (gland and stroma) outside the uterus. It is estimated to occur in 10% of reproductive aged women and is associated with pelvic pain and infertility. The overall prevalence of endometriosis is greater in infertile women than in fertile women.3 The etiology of endometriosis is not exactly known, however, polymorphism studies on estrogen receptor (ER) associated with the risk of endometriosis in different countries showed that the risk of endometriosis varies and it is associated with genetic, environmental, and other numerous factors.4

There are many studies suggesting the causal relationship between the presence of endometriosis and subfertility, but the exact mechanism is still unclear.5 However, it is evident that when endometriosis is moderate to severe, involving the ovaries and causing adhesions that block tubo-ovarian motility and ovum pickup, it is associated with subfertility.6,7 Because benign ovarian cysts including endometrioma are frequently encountered in women of reproductive age, fertility preservation is important in patient management.

Assessment of ovarian reserve is an important issue in infertility.8,9 Several serologic tests, such as basal follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), estrogen, and inhibin B and ultrasonographic findings, such as ovarian volume and antral follicle count can be used to predict fertility, however, there are several limitations.8,9,10,11 Serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) is a dimeric glycoprotein within the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily, and is produced by the granulosa cells of primary to small antral follicles to prevent depletion of the primordial follicle pool. AMH levels are independent of the menstrual cycle and are not affected by the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists or oral contraceptives. Hence, serum AMH measurement has been widely used in clinical practice for assessment of ovarian reserve and is currently measured frequently during the initial work-up for infertility.12,13,14

Endometriosis is related to subfertility and many studies have shown corresponding results. Shebl et al.15 demonstrated the association between low serum AMH levels and severity of women with endometriosis. In addition, Campos et al.16 showed that patients with minimal to mild endometriosis have similar follicular-fluid AMH concentrations during natural in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle, as patients with tubal obstruction without endometriosis. Pacchiarotti et al.17 reported that serum AMH levels are reduced in women with endometriosis who have never undergone ovarian surgery, suggesting a state of poor ovarian reserve. However, it is unclear whether patients with endometriosis have a real decrease in ovarian reserve, furthermore, what causes the decreased ovarian reserve is unknown.

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether the preoperative serum AMH levels are lower in young women with ovarian endometrioma, as compared to other benign ovarian cyst. In addition, the differences of AMH changes according to various characteristics were investigated to demonstrate when surgeons could be concerned with ovarian reserve before ovarian surgery.

Material and Methods

1. Study population

Before ovarian surgery, serum AMH levels were measured between March, 2011 and September, 2014 at Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital. Total 97 patients aged 20 to 39 years who were diagnosed with ovarian endometrioma or benign ovarian cyst by histopathologic confirmation were enrolled. Exclusion criteria consisted of the followings: 1) confirmed polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), 2) previous history of ovarian surgery (including oophorectomy and cystectomy), 3) endocrine disorder such as hyperprolactinemia or thyroid dysfunction, and 4) oral contraceptives or hormone use.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital.

2. Pelvic ultrasonography

All the included patients underwent transvaginal or transrectal ultrasonography preoperatively to examine the size and characteristics of the ovarian cysts. Ultrasound examination was performed with a 7-MHz transvaginal transducer (Logic 400 General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) or transrectally for virgin patients.

Mean, maximum, and total diameter of cysts were measured. Mean diameter of cyst was calculated by averaging the maximum diameter of cyst and its vertical diameter. Total diameter of cyst was calculated by summation of each cyst's mean diameter, when cysts were multiple. According to the characteristics of cysts, the patients were divided into 4 groups i.e., single unilateral, single bilateral, multiple unilateral, and multiple bilateral.

3. AMH measurements

Before the operation, blood samples were obtained by venipuncture and the venous blood samples were taken after overnight fasting for at least 8 hours, during their follicular phase of menstrual cycle. In the case of women with amenorrhea, blood was sampled considering the ovarian morphology investigated by ultrasound.

The serum AMH level was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (AMH Gen II ELISA, Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The kit has sensitivity of 0.57 pmol/L and reported intra- and interassay coefficients of variation of < 5.6%, according to the products' inserts.

Between endometrioma and other benign ovarian cyst groups, serum AMH levels were compared and analyzed according to size of ovarian cysts and age-matched AMH quartile percentile. In endometrioma group, AMH levels and age-matched AMH quartile percentile were compared according to characteristics of ovarian cysts. The age-matched AMH quartile percentile was based on normal levels in 1,298 Korean women with regular menstruation.18

4. Surgical procedure

All patients underwent laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy under general anesthesia. The surgery was performed either by multi-port or single-port technique. All specimens obtained intra-operatively were submitted for pathologic examination.

5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 20 (Statistical Package for Social Science Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Subjects were divided into 2 groups based on pathology (endometrioma or other benign ovarian cysts) and AMH differences between the 2 groups were determined by Student's t-test and χ2 test. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to analyze correlation between AMH levels and mean, maximum, total diameters, number of ovarian cysts. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

In total, 97 patients were divided to 2 groups by pathologic confirmation. Sixty-five patients were diagnosed with ovarian endometrioma and 32 patients had other benign ovarian cysts. The mean age of endometrioma group was 30.3 ± 4.4 years and 27.6 ± 4.2 years in other benign ovarian cysts group. Mean age was significantly older in the endometrioma group than other ovarian cyst group. The 32 patients with other benign ovarian cysts were as follows: 24 patients with mature cystic teratoma, 4 patients with mucinous cystadenoma, 2 patients with serous cystadenoma, 1 patient with adenofibroma, and 1 patient with serous adenofibroma and mucinous cystadenoma.

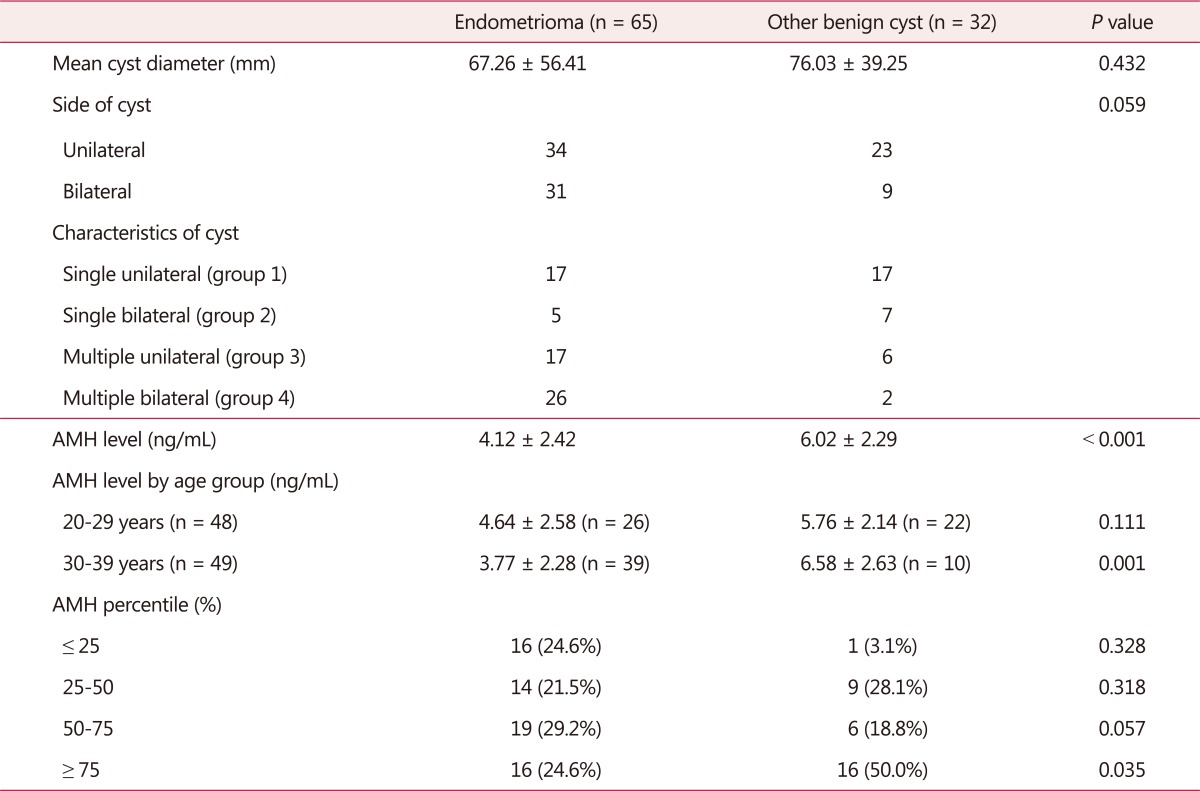

Mean diameter of endometrioma group was 67.26 ± 56.41 mm, and 76.03 ± 39.25 mm in other benign cyst group. The difference was not statistically significant. Among the 65 patients with endometrioma, 34 patients had unilateral endometrioma and 31 patients had bilateral endometriomas. Grouping by bilaterality and multiplicity, single unilateral (group 1) were 17, single bilateral (group 2) were 5, multiple unilateral (group 3) were 17, and multiple bilateral (group 4) were 26 (Table 1). In all patients with ovarian endometrioma, advanced endometriosis (stage III and IV) was diagnosed by laparoscopy.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels in patients with ovarian endometriomas compared to other benign ovarian cysts.

AMH: anti-Müllerian hormone

Preoperative serum AMH level was 4.12 ± 2.42 ng/mL in endometrioma group and 6.02 ± 2.29 ng/mL in other benign cyst group. Although there is a limitation that age was significantly different between 2 groups, the result indicated that AMH level was significantly lower in endometrioma group (P < 0.001).

Divided by age group, serum AMH level was 4.64 ± 2.58 ng/mL in endometrioma group aged 20 to 29 years and 5.76 ± 2.14 ng/mL in other benign cyst group aged 20 to 29 years. In endometrioma group aged 30 to 39 years, serum AMH level was 3.77 ± 2.28 ng/mL and 6.58 ± 2.63 ng/mL in other benign cyst aged 30 to 39 years group. According to the result, serum AMH level was significantly lower in endometrioma group, especially in patients aged 30 to 39 years.

Patients were divided into 4 groups, by AMH percentile according to age-specific serum AMH level in Korean women, as ≤ 25 percentile, 25 to 50 percentile, 50 to 75 percentile, and ≥ 75 percentile. Thus, in endometrioma group, 16 patients (24.6%) were ≤ 25 percentile, 14 (21.5%) were 25 to 50 percentile, 19 (29.2%) were 50 to 75 percentile, and 16 (24.6%) were ≥ 75 percentile. In other benign cyst group, 1 (3.1%) was ≤ 25 percentile, 9 (28.1%) were 25 to 50 percentile, 6 (18.8%) were 50 to 75 percentile, and 16 (50.0%) were ≥ 75 percentile. There was a significantly higher proportion of patients with AMH level ≥ 75 percentile in other benign cyst group (P = 0.035) (Table 1).

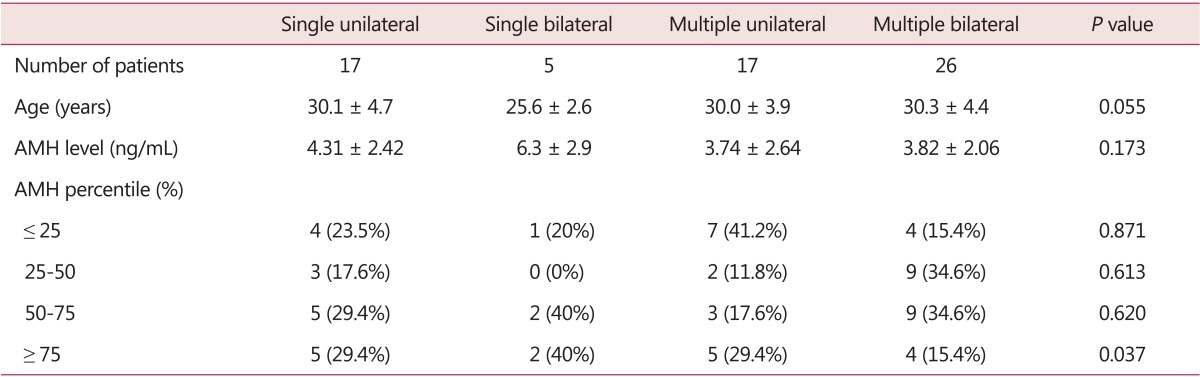

AMH levels were not significantly different between the 4 groups divided by bilaterality and multiplicity and mean age. However, according to the AMH percentile, patients with AMH level ≥ 75 percentile were significantly decreased in multiple bilateral endometrioma group (Table 2).

Table 2. The serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels in patients with different characteristics of endometriomas.

AMH: anti-Müllerian hormone

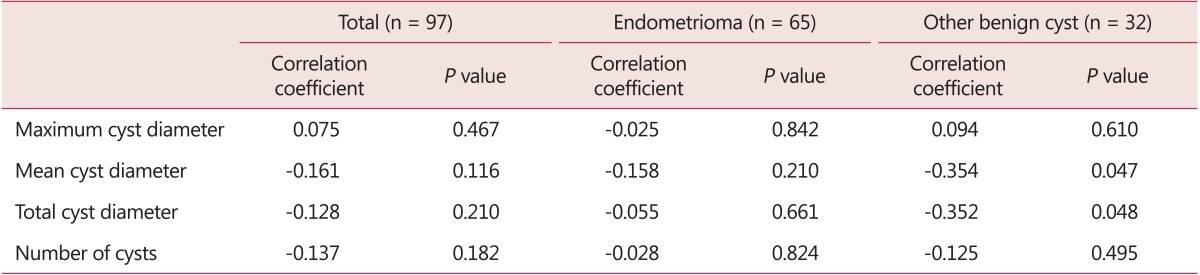

By Pearson correlation coefficient, mean and total diameter of cysts were negatively correlated with preoperative serum AMH level in other benign cyst group (Table 3).

Table 3. Univariate analysis of variance to evaluate the correlation with serum anti-Müllerian hormone level.

Discussion

The present study was designed to compare the preoperative serum AMH levels between endometriomas and benign ovarian cysts. Our results showed that preoperative AMH level was significantly lower in endometrioma group than other benign ovarian cyst group in similar sized diameter. Additionally, this difference was statistically significant, especially in 30 to 39 years old. Increasing exponential follicle loss after the age of 30 years might aggravate the impact of endometrioma on diminished ovarian reserve.

Although it is not yet definite whether the ovarian reserve is diminished in patients with endometriosis, several studies demonstrated decreased ovarian reserve in endometriosis patients. Follicular density in cortex from ovaries with endometriomas is lower19 and increased oxidative stress in ovarian cortex around endometriomas might induce follicular depletion.20 By space-occupying effects and local reactions, cysts can reduce the amount of functional ovarian tissue available, and endometriosis-related inflammation causes ovulatory dysfunction, disturbed folliculogenesis, decreased oocyte quality, and increased granulosa cell apoptosis.21,22,23

AMH appears in the fetal period and decreases continuously throughout puberty. It becomes undetectable when menopause occurs, identifying it as a typical hormone of reproductive age.24,25 The levels of AMH reflect the number of preantral follicles; that comprise the oocyte pool. Moreover serum levels of AMH are highly correlated with the antral follicle count assessed by ultrasonography and also with AMH concentrations measured in the follicular fluid.26 Recently, AMH has been used in initial fertility work up and follow up studies on ovarian damage due to chemotherapy, ovarian surgery of diseases like endometriosis.27

As in endometriosis, majority of studies investigated AMH as an assessment tool for ovarian reserve depletion after ovarian surgery,28,29,30 predictive responses to assisted reproduction techniques.31,32,33 Endometriosis possibly related to infertility or subfertility. Endometriosis can have direct effect on ovarian reserve and presents with low serum AMH level without previous ovarian surgery or regardless of their fertility state.

In this study, we investigated the ovarian reserve impairment according to AMH percentile by age-specific serum AMH levels in Korean women and various characteristics. The patients with AMH level ≥ 75 percentile were significantly decreased in endometrioma group, especially in multiple bilateral group. Ovarian follicles are firmly adjacent to endometrioma with tissue alteration unlike other benign ovarian cysts and endometrioma may invade the ovarian cortex causing direct damage to ovarian follicles. Therefore, multiple bilateral endometrioma could affect the ovarian reserve negatively although there are limited data on how the endometrioma size contributes to ovarian function. In other benign cyst group, we demonstrated that preoperative AMH level was correlated negatively with mean and total diameter of cysts. The impact of endometrioma on ovarian reserve is assumed to appear earlier as in big-sized other benign cysts.

Social trends suggest that Korean women desire pregnancy at an increasing age; therefore, the importance of ovarian function preservation is emphasized up to late age. Furthermore, the risk of decreased ovarian reserve cannot be overlooked if women of reproductive age have to undergo ovarian surgery before childbearing.

Our results showed, that preoperative AMH measurement might be helpful in women with endometrioma, especially in those who are 30 to 39 years old and have multiple bilateral type of endometriomas. In women with other benign ovarian cysts, preoperative AMH measurement might be considered when the size is big. In these cases, we suggest that surgeons could consider the risk of diminished ovarian reserve before surgery as well as after surgery for the future pregnancy.

There is still insufficient data to compare age-specific AMH and analyze according to stage and score of endometriosis because the endometrioma group was limited in advanced endometriosis. A limit of this study is the small number of patients sampled.

Further larger studies will be required to confirm whether the reduced ovarian reserve precedes ovarian surgery in women with endometrioma, differing from other benign ovarian cysts.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Kim CR, Ku CH, Jeon IS, Son DW, Lee JS. The clinicopathologic features and significance of preoperative CA 125 in patients who had an operation for ovarian tumors. J Korean Soc Menopause. 2013;19:26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park JW, Hwang SO, Park JH, Lee BI, Lee JH, Kim KW, et al. Discrimination between benign and malignant pelvic masses using the risk of malignancy index 1. J Korean Soc Menopause. 2013;19:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins. ACOG practice bulletin. Medical management of endometriosis. Number 11, December 1999 (replaces Technical Bulletin Number 184, September 1993). Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2000;71:183–196. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)80034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mun MJ, Kim JH, Kim TH, Hwang JY, Jang WC. Associations between estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms and endometriosis. J Korean Soc Menopause. 2013;19:64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Hooghe TM, Debrock S, Hill JA, Meuleman C. Endometriosis and subfertility: is the relationship resolved? Semin Reprod Med. 2003;21:243–254. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benaglia L, Somigliana E, Vercellini P, Abbiati A, Ragni G, Fedele L. Endometriotic ovarian cysts negatively affect the rate of spontaneous ovulation. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2183–2186. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The American Fertility Society. Classification of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1979;32:633–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gleicher N, Weghofer A, Barad DH. Defining ovarian reserve to better understand ovarian aging. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sills ES, Alper MM, Walsh AP. Ovarian reserve screening in infertility: practical applications and theoretical directions for research. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Azemi M, Killick SR, Duffy S, Pye C, Refaat B, Hill N, et al. Multi-marker assessment of ovarian reserve predicts oocyte yield after ovulation induction. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:414–422. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shin SY, Lee JR, Noh GW, Kim HJ, Kang WJ, Kim SH, et al. Analysis of serum levels of anti-Mullerian hormone, inhibin B, insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3, and follicle-stimulating hormone with respect to age and menopausal status. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23:104–110. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Marca A, Sighinolfi G, Radi D, Argento C, Baraldi E, Artenisio AC, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) as a predictive marker in assisted reproductive technology (ART) Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:113–130. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cate RL, Mattaliano RJ, Hession C, Tizard R, Farber NM, Cheung A, et al. Isolation of the bovine and human genes for Müllerian inhibiting substance and expression of the human gene in animal cells. Cell. 1986;45:685–698. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90783-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toner JP, Seifer DB. Why we may abandon basal follicle-stimulating hormone testing: a sea change in determining ovarian reserve using antimullerian hormone. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1825–1830. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shebl O, Ebner T, Sommergruber M, Sir A, Tews G. Anti muellerian hormone serum levels in women with endometriosis: a case-control study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25:713–716. doi: 10.3109/09513590903159615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campos CS, Vaamonde D, Andreoli C, Martins AC, Genro VK, Souza CA, et al. Follicular-fluid anti-Müllerian hormone concentration is similar in patients with endometriosis compared with non-endometriotic patients. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;21:470–473. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pacchiarotti A, Frati P, Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Gentile V, Moscarini M. Evaluation of serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels to assess the ovarian reserve in women with severe endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;172:62–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoo JH, Kim HO, Cha SW, Park CW, Yang KM, Song IO, et al. Age specific serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels in 1,298 Korean women with regular menstruation. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2011;38:93–97. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2011.38.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitajima M, Defrère S, Dolmans MM, Colette S, Squifflet J, Van Langendonckt A, et al. Endometriomas as a possible cause of reduced ovarian reserve in women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:685–691. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Li XH, Ma X, Wang ZH, Lu S, Guo YL. Redoxinduced apoptosis of human oocytes in resting follicles in vitro. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006;13:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halis G, Arici A. Endometriosis and inflammation in infertility. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1034:300–315. doi: 10.1196/annals.1335.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stilley JA, Birt JA, Sharpe-Timms KL. Cellular and molecular basis for endometriosis-associated infertility. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;349:849–862. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1309-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta S, Goldberg JM, Aziz N, Goldberg E, Krajcir N, Agarwal A. Pathogenic mechanisms in endometriosis-associated infertility. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Vet A, Laven JS, de Jong FH, Themmen AP, Fauser BC. Antimullerian hormone serum levels: a putative marker for ovarian aging. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:357–362. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02993-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee MM, Donahoe PK, Hasegawa T, Silverman B, Crist GB, Best S, et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance in humans: normal levels from infancy to adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:571–576. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.2.8636269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaya C, Pabuccu R, Satiroglu H. Serum antimüllerian hormone concentrations on day 3 of the in vitro fertilization stimulation cycle are predictive of the fertilization, implantation, and pregnancy in polycystic ovary syndrome patients undergoing assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2202–2207. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.La Marca A, Broekmans FJ, Volpe A, Fauser BC, Macklon NS. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH): what do we still need to know? Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2264–2275. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang HJ, Han SH, Lee JR, Jee BC, Lee BI, Suh CS, et al. Impact of laparoscopic cystectomy on ovarian reserve: serial changes of serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Streuli I, de Ziegler D, Gayet V, Santulli P, Bijaoui G, de Mouzon J, et al. In women with endometriosis anti-Mullerian hormone levels are decreased only in those with previous endometrioma surgery. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:3294–3303. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Somigliana E, Benaglia L, Vigano P, Candiani M, Vercellini P, Fedele L. Surgical measures for endometriosis-related infertility: a plea for research. Placenta. 2011;32(Suppl 3):S238–S242. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Carvalho BR, Rosa-e-Silva AC, Rosa-e-Silva JC, dos Reis RM, Ferriani RA, de Sá MF. Anti-müllerian hormone is the best predictor of poor response in ICSI cycles of patients with endometriosis. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falconer H, Sundqvist J, Gemzell-Danielsson K, von Schoultz B, D'Hooghe TM, Fried G. IVF outcome in women with endometriosis in relation to tumour necrosis factor and Anti-Müllerian hormone. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;18:582–588. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papaleo E, Ottolina J, Vigano P, Brigante C, Marsiglio E, De Michele F, et al. Deep pelvic endometriosis negatively affects ovarian reserve and the number of oocytes retrieved for in vitro fertilization. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:878–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]