Intimate partner violence (IPV) involves intentionally inflicted harm (physical, sexual, and psychological) by a current or former intimate partner (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Although reports of IPV decrease as victims grow older, the problem does not dissipate. Bonomi and colleagues (2007) reported a lifetime prevalence of partner violence of 26.5% for women aged 65+. A review of Adult Protective Services (APS) data from 10 states revealed that 11% of the substantiated reports of abuse of persons aged 60+ by a known perpetrator involved a spouse/intimate partner (Teaster, Dugar, Mendiondo, Abner, Cecil, & Otto, 2006). Similarly, national data indicated that of the 9.0% of respondents aged 57+ who reported past year verbal mistreatment, 26.2% identified a spouse or romantic partner as the perpetrator and of the 2.0% who reported physical mistreatment, 19.6% identified a spouse/partner as the person responsible (Laumann, Leitsch, & Waite, 2008).

The steady growth of domestic violence (DV) services across the United States has helped improve public awareness of IPV and stimulated thinking about it as a community problem (Carlson & Worden, 2005). However, incidences of IPV in late life are often obscured under the broad umbrella of elder abuse, which does not resonate with community DV service providers and advocates and gives disproportionate attention to abuse perpetrated by adult children and caregivers (Desmarais & Reeves, 2007). The purpose of this study was to examine community professionals’ awareness and perceptions of and experience with IPV in late life.

Community Perspectives

The extant literature has identified experiential, cultural, and social factors, including social media (Brossoie, Roberto, & Barrow, 2012), that shape societal perceptions of and response to elder abuse and likely influence community professionals’ beliefs about IPV in late life (Roberto, Teaster, McPherson, Mancini, & Savla, 2015). Moreover, Jakobsson and colleagues (2013) found that professionals who reside in the communities they serve tend to mirror the attitudes and perspectives of the local culture. Thus, as the greater community increasingly acknowledges abuse, professional support is also likely to increase (Carlson & Warden, 2005). In this transitioning process, professionals will need assistance with recognizing signs and symptoms of abuse (Podnieks & Wilson, 2004), building consensus on what constitutes abuse, and agreeing upon sentencing protocols for perpetrators (Payne, Berg, & James, 2001).

In rural communities, professional awareness and response to IPV remains quite limited because the culture of self-sufficiency, patriarchal social structures, limited community service options, social and geographic isolation, and widespread economic hardships contribute to and conceal violence in relationships (Hornosty & Doherty, 2003; Riddell, Ford-Gilboe, & Leipert, 2009). These same factors also challenge the ability of the local criminal justice system to investigate and prosecute offenders (Teaster, Roberto, & Dugar, 2006; Websdale, 1997). The rural professional’s willingness to support victims may be hampered further when both victim and perpetrator are clients of the helping professional or related to the provider. In such situations, abuse generally is overlooked and offers of support are withheld (Hornosty & Doherty, 2003; Websdale, 1997).

Our research is guided by a socioecological framework, grounded in earlier research on elder abuse (Horsford, Parra-Cordona, Post, & Schiamberg, 2010; Roberto et al., 2015; Teaster, Roberto, et al., 2006) and theoretical work on building community capacity (Bowen, Martin, Mancini, & Nelson, 2000; Mancini, Nelson, Bowen, & Martin, 2006). The ecological framework facilitated our understanding of IPV in late life as a complex problem requiring systemic and coordinated responses from different levels of intervention (Teaster, Roberto, et al., 2006). Because IPV occurs in a community context, responses and solutions must include not only the victims, but also the broader environment. The community’s ability to respond to problems, such as IPV, is based on how well its members join together to demonstrate a sense of shared responsibility for the welfare of each other and the community (Bowen et al., 2000). By considering informal relationship networks (e.g., family, friends, neighbors) and formal support systems (e.g., legal, health, religious) that operate within the community and the ideological values and social norms held by community members, IPV can be better understood and effectively addressed (Mancini et al., 2006). Utilizing this prospective, we examined personal and professional awareness of IPV, individual perceptions about victims and their help-seeking behaviors, professional response protocols, and professionals’ interdisciplinary experience in responding to incidents of IPV in late life.

Methods

The project represented an academic-community partnership between researchers from the Center for Gerontology at Virginia Tech and the Women’s Resource Center (WRC), a local DV agency serving victims of violence in four rural counties and an independent city within the Appalachian region of southwest Virginia (see Roberto, Brossoie, McPherson, Pulsifer, & Brown, 2013 for project details). The WRC community advisory group, known at the time of the study as the New River Valley Task Force on Domestic Violence Among Older Adults, also provided regular input and guidance to the project. The Task Force included 47 members representing victims and community service professionals in law enforcement, healthcare, social services, long-term care, the faith community, and academia. At the time of the project (2007–2010), residents of the region were predominately White (93%); 14.0% of the population lived below the federal poverty level and 13.5% of the population were aged 65 and older (U.S. Census Bureau, 2007).

Study Sample and Procedures

This research was approved by the institutional review board of Virginia Tech. As part of the larger project, 12 focus groups were held with 72 local community professionals who were likely to encounter older female victims of IPV. An additional 15 community professionals who were unable to attend the focus groups were interviewed by telephone. Participants were identified and recruited by mail and telephone using the networks of Task Force members and the project team. The 87 participants included members of the criminal justice system (police officers, detectives, and lawyers; n=7), social workers (regional administrators and APS staff; n=9), WRC staff and victim advocates (n=10), mental health counselors (public and private; n=7), primary care doctors, emergency healthcare providers (emergency medical technicians (EMT), forensic nurses, and emergency room (ER) physicians; n=10), aging services professionals (home and community-based service providers, nursing home providers, hospice providers, local Agency on Aging staff, and a Long-Term Care (LTC) Ombudsman; n=11), clergy (senior pastors, ministers, priests, and bishops; n=7) and lay clergy (parish nurses, and older adult ministry volunteers; n=6), and community leaders (business owners and managers in housing, mental health, charities, academia, and family counseling; n=20).

Groups were configured by profession, which allowed for more free-flowing conversations among participants with similar roles and expertise as well as facilitated the analyses of differences in perspective between professional groups (Morgan & Krueger, 1997). Written informed consent was received from each of the focus group participants at the beginning of each session. Similarly, verbal consent was received from each person who participated by telephone prior to the start of the interview.

Sample selection techniques included both intensive and maximum variety strategies (Patton, 2001). We over-recruited by at least 20% per group to ensure professional and geographic representation from each of the four rural counties and one small independent city (Morgan & Krueger, 1997). Ultimately, each professional group was represented by at least one person from each region. The 87 participants reflected the racial make-up of the region and included 61 females (70.1%) and 26 males (29.9%) ranging in age from 22 to 71 (M=49.7; SD=11.3). On average, participants were in their professional position for 10.3 years (SD=9.4; range 1–40) and lived in their rural communities for 24.4 years (SD=15.3; range 1–59), suggesting professional commitment and strong ties to their communities.

Standard focus group methodology was followed to collect the data (Morgan & Krueger, 1997). Questions were generated based upon our conceptual framework and pilot-tested with members of the task force. The focus group facilitator (first author) promoted interactions among group members, guided by a pre-established list of probing questions to focus or expand discussions. The questions were designed to elicit predominant values and beliefs held by participants with respect to perceptions of and experience with responding to IPV in late life (see Table 1). Participants received ample time to respond to the questions/follow-up probes and provided opportunities to elaborate on and clarify their answers. The community professionals interviewed by telephone responded to the same questions posed to the focus group participants. Focus groups lasted approximately two hours and telephone interviews took one-half hour. Both the focus groups and telephone interviews were audio-recorded. Responses from individuals interviewed mirrored those of the focus group participants; thus, we analyzed the data collectively.

Table 1.

Focus Group/Interview Questions for Community Professionals

| Key Questions | Domain |

|---|---|

| 1. What are the common characteristics of older victims of IPV? | Individual Perceptions |

| 2. What factors influence an older woman’s decision to seek and accept help from others in her community? | |

| 3. How often in the course of your work do you come in contact with older women who are victims of IPV? | Professional Experiences |

| 4. Are individuals within your agency specifically as work with or called in to work with older victims of IPV? | |

| 5. How do older women come to your attention as wanting or needing help? | Organizational Responses |

| 6. What role does your agency or organization play in helping them be safe and rebuild their lives without violence | |

| 7. Which agencies or professional groups are you more likely to work with when helping older victims? | |

| 8. What professional mandates, or organizational policies prohibit you from addressing IPV effectively? | |

| 9. How willing do you think the NRV community will be to implement a community response model for older women? | Collaborative Community Responses |

Consistent with established qualitative analysis procedures, data collection, coding, and analysis were ongoing and integrated (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Such ongoing analysis allowed us to identify and obtain insights on previously unexplored phenomena that emerged as critical and eliminate lines of questioning that appeared tangential or irrelevant. Analysis of the data occurred in three phases (Morgan & Krueger, 1997). The first phase occurred during sessions/interviews when the facilitator decided which responses to probe further and which to redirect. The second phase occurred following each session/interview when the facilitator and co-facilitator, who also served as the note-taker, shared their observations and perceptions of the group members’ interactions with the research team and identified major themes of the session. At the completion of each focus group/interview, a professional transcriptionist transcribed the recorded session verbatim; however speakers were not tracked individually. The facilitator reviewed each transcript for accuracy, comparing the recording to the transcription content. In the last phase of the data analysis, the transcriptions and notes were reviewed and coded by the authors without the use of qualitative software.

Team members independently read the transcripts and identified an initial set of primary codes (e.g., awareness of problem, actions taken, and interprofessional collaborations), which were manually applied to the transcripts. Conflicts in coding were discussed as a team until consensus was reached. Next, team members reread the transcripts and focused on identifying the underlying assumptions, attitudes, and experiences shared within each primary code. The secondary coding framework included themes (e.g., ageism, filial responsibility, personal responsibility and accountability) that could be attributed to victims and their families, providers and the professions in which they worked, and the greater community. During analysis, participant quotes that best represented a theme were identified for use in reporting the study findings.

Applying the principles of effective data analysis for qualitative designs (Anfara, Brown, & Mangione, 2002), we developed rich descriptions of the community professionals’ perspectives through the construction of a coding frame for use in cross-respondent (and group of respondents) analysis of the transcript data. We established dependability by seeking data from multiple sources (e.g., seeking input from an array of community providers, and obtaining guidance from professionals in making sense of policies and protocols existing within a profession), employing a code-recode strategy, and seeking confirmation from community partners (e.g., Task Force).

Findings

Participants shared similar levels of awareness of IPV in late life and held comparable perceptions of victims and abusers, thus limiting the utility of making comparisons across professional groups. Highlights of the shared perspectives are presented along with participant quotes to showcase the scope and depth of their viewpoints.

Awareness of IPV in Late Life

To gauge awareness of IPV in late life we asked participants, “How often in the course of your work do you come in contact with older women who are victims of IPV?” Across the groups, the silence and shaking of heads revealed that participants could not readily identify a time when they worked with an older female victim of IPV. One aging services provider explained that her struggle and the struggles of others had to do with age, “When you talk about intimate partner violence, the first thing that comes to mind is a younger face. We don’t normally associate it with an older person.” However, as participants shared and discussed situations that they encountered involving domestic or family violence, they recognized that IPV could have been a problem even though they did not recognize it at the time and could not articulate it earlier in the focus group discussion. Still, with the exception of emergency healthcare providers, lawyers, lay clergy, and WRC staff, few participants were able to recall ever working with an older female victim of IPV.

Participants reasoned that their awareness of IPV in late life was limited largely because older women had not been asking them for help so they were unaware that it was a problem. Secondly, they did not have scholarly information that indicated it was a problem. Several participants admitted that they participated in the study because they figured if researchers were talking about IPV in late life, it must be a problem and they wanted to learn more.

Participants’ lack of awareness also was fueled by a shared assumption that individuals “mature out” (Winick, 1962) or grow too old to engage in violent relationships. Some participants came to the session assuming that IPV in late life was associated with cognitive impairment. That is, a husband with Alzheimer’s disease might suddenly attack his wife or a frustrated caregiver might handle his wife with dementia roughly; something neither person would have imagined doing in healthier times. Participants viewed both acts as wrong, but given the circumstances, understandable and forgivable.

It was challenging for some participants to accept IPV in late life as an issue deserving their attention. While it was an important issue, it was not as pressing as other persisting problems, such as child abuse. They explained that adults are responsible for handling their own problems, while children are not. One parish nurse was quick to point out that she would report abuse against an adult “if the abuse was bad enough;” although she could not articulate what her reporting threshold might be. Another lay clergy member solemnly added, “We just take the child more seriously than we do the adult.”

Perceptions of Victims and Help-Seeking Behaviors

When participants were asked to describe a typical older victim of IPV, inevitably their initial response was that she was poor, uneducated, in poor health, dependent on others, isolated, and possessed low self-esteem. Again, as conversations unfolded and professional experiences shared, a more inclusive description emerged; the typical victim became “any woman.”

Participants who worked with older victims (e.g., emergency healthcare providers, police, victim advocates), were quick to share that while some women can keep the violence in their lives secret and outwardly project living normal lives, other women keep it secret but act nervous or anxious – distinctions not lost on one EMT.

There have been times when we found out later that someone was a victim of violence and we honestly couldn’t tell because they acted normal, they seemed fine, and gave no clues … Then there are others, when we come into their houses, it’s like they are afraid we will see something; always looking over their shoulder.

EMTs and forensic nurses suggested it was easier to identify an alleged male perpetrator than a victim. They noted that in an emergency healthcare situation he will typically answer every question posed to the victim, even those not related to the presenting problem. The alleged perpetrator would also insist on accompanying his female victim everywhere during her healthcare visit, including the bathroom. Moreover, he was likely to pull staff aside to discuss her physical and mental shortcomings and confide in them about how her medical needs have become a burden or how her behaviors restrict him from living the lifestyle he truly deserved.

Participants across the groups offered several similar reasons why older women remained in violent relationships. Love for the abuser, especially if the abuser was cognitively impaired, was a common explanation. Despite having affections for their abusers, participants perceived the women as fearful; thus, making them unwilling or unable to leave. They agreed it was probably easier for an older woman to remain in a violent relationship than to leave behind personal belongings, property, financial security, and a lifetime of memories and family relationships, especially when leaving everything for the abuser to enjoy or destroy. One aging service professional commented, “It’s easier to be with somebody who is being abusive than to go without, because growing old already consists of losses.”

Older abused women frequently were described as stuck or frozen in their situation because of a lack of resources and support. One primary care doctor described such victims as, “… having no skills. They can’t get a job. They can’t take care of themselves. They don’t feel confident being on their own and they don’t have anywhere to go.” In addition to needing resources to support themselves, participants added that many women would also need to find shelter for their livestock. They explained that abusers in rural areas often keep victims silent (regardless of age) by threatening the welfare of family livestock and pets.

Even if older women wanted to leave their abusive situations, participants across the groups stressed that strong cultural values and expectations prevented them from seeking help. The value of self-sufficiency coupled with solid distrust of government intervention and outsiders offering help permeated life in the region. One community leader emphasized that the pressure to keep family problems in the family and hidden was vital, especially for residents living in the public eye.

There is a stigma attached that you don’t want to report problems. You don’t want anyone to know your business. If you’re an upstanding citizen in the community, you certainly can’t be seen as abusive or in an abusive relationship— so you hide it.

Participants also stressed that the social expectation that a marriage lasts forever loomed large. Separation or divorce was not a viable option for older women. They frequently used the old adage ‘you’ve made your bed, now lie in it’ to describe how older women were expected to respond to marital difficulties. Participants also suspected that the teachings of the fundamentalist Christian churches dotting the region likely encouraged victims to remain in abusive marriages by emphasizing the threat of spending eternity in hell if they were to leave.

Assumptions about Seeking Help

If victims were looking for help or information about local resources, participants from most groups overwhelmingly assumed that they turned to their church leaders or primary care doctors for answers. They reasoned that because physicians and the clergy were enmeshed in the fabric of rural life and had contact with many community members, they possessed insights into people’s lives — a hypothesis both professional groups soundly rejected. One pastor offered, “I think that a person would be fairly desperate to come to me because I think there’s a lot of shame associated with doing that.” Another minister added that his parishioners were fully aware that he was mandated by law to report charges of DV, which discouraged them from sharing personal matters with him. One aging services professional suggested that pastors might actually be the last persons victims turn to for help for fear of losing their social standing and community connections, “A deacon’s wife wouldn’t seek any kind of help that would cause him shame because she would also lose her personal status in the church.” Among physicians interviewed, one primary care doctor believed that only when a victim was ready to leave a violent relationship, would she admit to being abused. Until that time, she would only ask for medications for her aches and pains or “nerves”— a regional term for a range of symptoms including anxiety and depression.

Collectively, the participants also assumed that older victims contacted the WRC emergency hotline when they wanted to talk about their abuse; again, not an entirely accurate assumption. Participants praised the staff and services of the WRC and assumed that it had the resources needed to work with older women. However, when pushed, many admitted that they did not know exactly what services were available and the extent to which staff could actually provide help.

Professional and Organizational Responses

Although researchers and service providers have argued that cross-system collaboration is crucial for successful community response to violence and abuse in late life (Tetterton & Farnsworth, 2011), participants in the current study acknowledged that they most often responded to reports of IPV against older women from the vantage point of their own professional domain. They identified multiple challenges to addressing IPV with the older women they encountered and coordinating assistance and services within the community.

Non-emergency encounters

With few exceptions, participants providing non-emergency services (i.e., mental health counselors, lawyers, primary care doctors, clergy/lay clergy, aging services professionals) were unlikely to address IPV during a crisis. Their support was in response to concerns brought to their attention by their clients. Although participants speculated that abuse might be occurring in their clients’ lives, it was not a concern typically brought up by their clients and not a concern the participants shared. U.S. laws protecting client confidentiality and privileged communications (e.g., HIPAA, Federal Public Health code regulations) and professional codes of ethics prohibited most professionals from discussing the matter with other providers without the individual’s consent. For example, lawyers frequently suspected that their clients were victims of IPV, but unless specifically asked to address victimization, they did not raise the issue while providing legal services.

Even though participants were adamant about protecting their client-provider relationships, many recognized that communications between professionals could potentially benefit victims. One mental health counselor recalled how her success working with an older client could have been improved if she had access to additional information.

I had a client for four years who was 68 when I started seeing her. She talked about horrible childhood sexual abuse and always talked about how supportive her husband was. He would even come to some meetings with her.…he was her hero. They had been married some 40 years. [When] she died and her children started to come to see me to tell me how abusive he had been to her her whole life. Yet, she never revealed that to me.

Mental health counselors speculated that aside from the social stigma attached to counseling by older generations, few older adults sought counseling because of financial reasons. Their agencies did not accept Medicare because reimbursement requirements were too difficult to meet. If an agency accepted Medicare, coverage was not comprehensive, resulting in out-of-pocket expenses for the recipient, another potential deterrent from seeking help.

None of the participating physicians reported having older patients come to them to specifically discuss IPV, although it may have been an underlying issue. Even though not required, some family doctors screened women of all ages for abuse. One male primary care doctor proudly announced, “Once a year when I see people, I am pretty systematic and ask, ‘Do you feel safe in your current living situation?’ And you know I’ve never had a woman over 50 say ‘No.’” When asked if this was because older women might not feel comfortable confiding in a younger man, he replied that there was no reason to be uncomfortable. He felt he provided a good opportunity for a victim to speak up and if she did not, that was her problem.

One female primary care doctor passively screened patients during their post examination discussions. She framed the screening tool and placed it where her patients, sitting across from her, could read it.

I’ll be talking to the patient about her health and she will look up and say, “Yes, 3, 7, 12”. … and I say, “Oh really. Let’s talk more about that”. Usually at that point, they’re not asking for help; they don’t want me to butt in.

Even though patients alerted this doctor to problems, they did not want her to take action. One older woman left this doctor’s practice after her multiple attempts to talk about the abuse.

I haven’t seen her [professionally] for a while but her unexplained injuries are getting worse. I am watching it as a community member and there’s nothing I can do. If you call the law, basically, they say well, she’s an adult, you know. Sorry.

Like other community professionals in the study, the primary care doctors reported referring troubled patients to counseling services and admitted being reluctant to counsel them, as addressing violent relationships was beyond their expertise. However, nearly all of the family doctors were comfortable prescribing medications for cases of “nerves” without the addition of counseling services. One primary care doctor defended this treatment approach stating, “It’s basically pay for performance and the big things we are looking at in adults over 65 are cancer, incontinence, obesity, and smoking. There’s no push to screen for depression or domestic violence with this group.”

Clergy members also could not recall any instances of IPV occurring within their congregations. Moreover, they were unaware of any church regulations to screen or report IPV, despite being able to cite regulations instituted to protect children from abuse within their churches. If clergy members became aware of an abusive situation, they reported being open to calling the police, after attempting to help the persons involved (victims and abusers) through pastoral counseling. They might also suggest seeking help from the family.

If counseling doesn’t help, we usually advise them to get the family aware of the situation … somebody that is caring … and can help the situation. If it’s manageable and you can keep the privacy of the family, then obviously you want to do that without reporting it.

Conversely, lay clergy reported having extensive knowledge of IPV among congregants, but did not share the information with anyone. They strongly believed that the issue was personal and not theirs to disclose or address. If their relationship with the victim was strong and the timing was right, they encouraged victims to resolve the problem themselves. One lay clergy member explained her reluctance to involve anyone outside the church:

I just don’t think that every case has to be a legal case. I think that’s contrary to our Christian tradition. We are taught upfront to work out problems before having to take them to court; to try to reconcile and mediate beforehand.

Like members of the clergy, aging services professionals generally addressed situations involving IPV internally; opting first for support from the LTC Ombudsman (in Virginia, Ombudsman have the responsibility to receive, investigate and resolve complaints made by or on behalf of older adults in nursing homes and assisted living facilities as well as community based long-term care services provided by state and private agencies) before contacting outsiders. Their reluctance to report to the police was rooted in the belief that once contacted, focus would shift from serving the victim to prosecuting the abuser. By utilizing the confidential mediation skills of the LTC Ombudsman, they believed victims would become better positioned and empowered to direct changes in their lives than if involved with the legal system. While not considered by participants from other fields as the best approach to helping victims, such an approach is reminiscent of the early grassroots helping efforts of listening and taking directions from victims of DV (Kulkarni, Bell, & Rhodes, 2012).

When participants were asked if they were willing to coordinate their efforts to address IPV, the prevailing sentiment was “Why fix something that isn’t broken?” For some participants, formal collaboration was simply out of their control. They needed sanction from their parent organization to proceed and that did not guarantee that they or their organization would remain committed. One senior pastor added,

My church loves to jump on the bandwagons, but they really don’t push the wagons that much. Every once in a while they’ll send out some brochures and tell you that it’s prevention week or some sort of thing. They really don’t send people around to help us address the issue.

Emergency situations

When discussing emergency responses, most participants identified APS as the agency that could and should intervene on behalf of older victims of IPV. However, participants representing the Department of Social Services (DSS), under which APS operates, were quick to clarify that APS’s ability to intercede is limited due to the absence of services for victims who are under age 60 and not disabled. An APS investigation cannot and will not be conducted unless age and disability criteria are met.

Police officers reported that they generally became aware of potential victims of IPV while responding to incidents involving alleged criminal acts (i.e., simple assault, aggravated assault) or domestic disputes. Additionally, emergency medical providers (hospital staff and EMTs) alerted them to potential victims receiving emergency medical treatment. In both situations, police officers stated that their primary focus was to ensure citizen safety and collect evidence to be used in the arrest and prosecution of alleged abusers. Depending on the officer, follow-up support to victims generally included referrals to community services and resources.

EMTs reported encountering situations involving violence against older women more frequently than ER physicians and forensic nurses. They reported picking up on cues that abuse might be a problem (e.g., wearing long sleeves in hot weather, furtive glances, anxious behaviors) even though it was not the reason for their visit. True to their mission, EMTs focused on the presenting tasks, and did not report their suspicions, stating there were no protocols in place for reporting.

Unlike the protocols in place for medical conditions, there is no standardization as to how we proceed. We don’t know what to do. We sometimes call DSS and hope for the best… we really don’t have follow-up, we don’t know what happens, we just hope for the best.

Participants clearly stated that their professional roles guided their responses to victims of IPV and their response did not change because of the situation, although they did accommodate the needs of other professionals working with the victim. Forensic nurses identified themselves as coordinators of care and investigation once potential victims were identified. After contacting local police, APS, and a victim advocate, they coordinated healthcare examinations and interviews with the police and APS to reduce the emotional impact and stress on the victim. While EMTs, forensic nurses and ER physicians were complimentary of the working relationship they had with the police, APS, and victim’s advocates, the competing missions of the professions sometimes created tension when not managed appropriately. One detective explained,

Everyone works pretty well together, but it’s trying. Everybody has a different mission. What everybody needs to do is just deal with their own mission; don’t infringe on mine and I won’t infringe on yours. So, if I need to speak to a victim and I want to explain to her what I have to do and what we need to do, don’t interrupt and tell her she has the right not to do that.

Despite differences in professional approaches to emergency and non-emergency situations, participants clearly respected each other’s professional missions and mandates and expressed a general willingness to collaborate when needed. Yet, many participants resisted endorsing a formal response effort to address IPV in late life as it has yet to emerge as a significant problem. One community leader explained, “Once people recognize there is a problem or an issue, they tend to rally around that and collaborate very well together and that includes, different agencies with different backgrounds …but we have to recognize it as a problem first.”

Discussion

From our analyses of the focus group and interview data, we identified three interrelated themes that contributed to the understanding of rural community professionals’ views on IPV against older women. First, as national data suggest, our study participants likely encountered victims of IPV, although most appeared unaware of the abuse at the time. This lack of awareness of IPV in late life is a reminder of the invisibility of older victims (Straka & Montminy, 2006) who are often overlooked by the community professionals in the best position to offer support. Second, perceptions of IPV were shaped by the social norms and cultural values in their communities as well as their professional lens. Although individuals perpetrate violence, it occurs in community and neighborhood contexts (Mancini et al., 2006). Thus, responses and solutions to IPV in late life must include not only a focus on victims and perpetrators, but also an understanding of the culture within the broader community. Third, professionals who collaborated to provide support to victims did so primarily during healthcare emergencies and largely because legally-mandated communications forced them to become involved (i.e., healthcare providers must notify the police and APS, and the police must contact APS). Working collectively and coordinating responsibilities across professional boundaries for IPV intervention can provide a more comprehensive and effective approach to address the safety and well-being of older IPV victims (Malik, Ward, & Janczewski, 2008; Roberto et al., 2015; Vinton & Wilke, 2014).

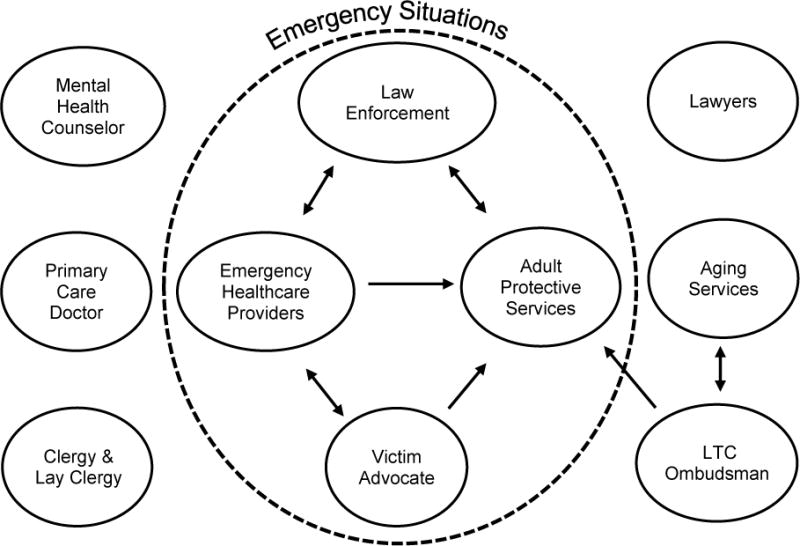

As depicted in Figure 1, the community professionals working in an emergency setting worked well together in restoring the immediate health and safety needs of victims. Conversely, professionals providing support to victims outside of emergency situations provide services characterized as fragmented. These silos of support resulted from professional mandates within each profession to maintain client confidentiality and prohibit professionals from exchanging information with other providers, even if they believed the client could benefit. Each profession included in the study could benefit from increased education and awareness about IPV in late life, screening and intervention tools, community services and resources, and interagency collaboration. If community professionals can gain these insights through continuing education and participation in collaborative response efforts, their willingness to share responsibility and demonstrate collective competence to reduce IPV is likely to improve (Roberto et al., 2015). As community professionals become more knowledgeable about IPV, they may also be more willing to initiate conversations about IPV with their clients and seek their permission to speak with other providers to link them with additional services.

Figure 1.

Interactions among professions responding to rural older victims of IPV

Raising awareness of IPV in late life and encouraging communication about it is a proactive step, but not an end goal. Service delivery systems must embrace community collaboration and develop a collective competence (Roberto et al., 2015). This involves disseminating information and building trust and reciprocity or social cohesion within communities. Client-centered and -directed models that can accommodate a variety of informal and formal networks providing support at different levels of frequency and intensity are warranted and likely to be more effective than current individual-level models functioning independently. By endorsing individualized and flexible service delivery models, professionals will be able to better engage victims in the solution process, leading to more promising long-term results (Beaulaurier, Seff, Newman, & Dunlop, 2005; Kulkarni et al., 2012). In this process, community professionals also must strive to be more empathetic, non-judgmental, empowering, ethical, and transparent in their efforts (Kulkarni et al., 2012) — characteristics not clearly articulated by or descriptive of most participants in this study.

For this project we limited our focused on IPV in late life wherein males were the perpetrators and females were victims. We recognize that IPV occurs among same-sex partners and includes female perpetrators and male victims. Future research must identify the unique needs of these older adults. Similarly, our findings may not be transferable to communities with more racially or ethnically diverse populations or other geographic locations (e.g., urban areas). For example, in urban areas, the working relationships and communications among networks of support (e.g., healthcare, aging services, faith community) may support older victims differently than in rural areas as there are more programs and portals to enter into services (Annan, 2008; Ruiz-Perez, Vives-Cases, Escriba-Aguir, Rodriguez-Barranco, & Nevot-Cordero, 2015). Victims can go unrecognized more easily in urban than rural areas because they have access to transportation and can go outside of their neighborhood and the watchful eyes of family and friends to seek help from providers who do not know them. Their ability to seek help outside of their immediate community can reduce the stigma, shame, and embarrassment experienced by rural victims (Annan, 2008). Nevertheless, our findings support other studies that report on the invisibility of IPV in late life in rural communities, contribute important new insights about community response, and lay the groundwork for further research and the development of more integrated community-based practice protocols to address this hidden, but widespread concern.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge research assistance provided by Marya McPherson, Mary Beth Pulsifer, and Detective E.M.E. Turner.

Funding: The project described was supported by Award Number R03HD059478 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) and the Office of the Director (OD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD or OD.

Contributor Information

Nancy Brossoie, Email: brossoie@vt.edu, Senior Research Associate, Center for Gerontology, Virginia Tech, 230 Grove Lane (0555), Blacksburg, VA 24061, Phone: 540-231-2335; FAX: 540-231-7157.

Karen A. Roberto, Email: kroberto@vt.edu, University Distinguished Professor, Center for Gerontology and The Institute for Society, Culture and Environment, Virginia Tech.

References

- Anfara VA, Brown KM, Mangione TL. Qualitative analysis on st age: Making the research process more public. Educational Researcher. 2002;31(7):28–38. doi: 10.3102/0013189x031007028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Annan SL. Intimate partner violence in rural environments. Annual Review of Nursing Research. 2008;26:85–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulaurier RL, Seff LR, Newman FL, Dunlop B. Internal barriers to help-seeking for middle-aged and older women who experience intimate partner violence. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. 2005;17(3):53–74. doi: 10.300/J084v17n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Reid RJ, Carrell D, Fishman PA, Rivara FP, Thompson RS. Intimate partner violence in older women. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:34–41. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GL, Martin JA, Mancini JA, Nelson JP. Community capacity: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Community Practice. 2000;8:1–21. doi: 10.1300/J125v08n02_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brossoie N, Roberto KA, Barrow KM. Making sense of intimate partner violence in late life: Comments from online news readers. The Gerontologist. 2012;52:792–801. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BE, Worden AP. Attitudes and beliefs about domestic violence: Results of a public opinion survey: I. Definitions of domestic violence, criminal domestic violence and prevalence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:1197–1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National intimate partner and sexual violence survey: Fact sheet. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. pp. 1–2. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv_factsheet2012-a.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais SL, Reeves KA. Gray, black and blue: The state of research and intervention for intimate partner abuse among elders. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2007;25:377–391. doi: 10.1002/bsl.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornosty J, Doherty D. Responding to wife abuse in farm and rural communities: Searching for solutions that work. In: Blake R, Nurse A, editors. The Trajectories of Rural Life: New Perspectives on Rural Canada. Regina: Saskatchewan Institute of Public Policy; 2003. pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Horsford S, Parra-Cordona JR, Post L, Schiamberg L. Elder abuse and neglect in African American families: Informing practice based on ecological and cultural frameworks. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect. 2010;23:75–88. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2011.534709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson A, Von Borgstede C, Krantz G, Spak F, Hensing G. Possibilities and hindrances for prevention of intimate partner violence: Perceptions among professionals and decision makers in a Swedish medium-sized town. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2013;20:337–343. doi: 10.1007/s12529-012-9238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni SJ, Bell H, Rhodes DM. Back to basics: Essential qualities of services for survivors of intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2012;18:85–101. doi: 10.1177/1077801212437137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Leitsch SA, Waite LJ. Elder mistreatment in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63(4):S248–S254. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.4.s248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini JA, Nelson JP, Bowen GL, Martin JA. Preventing intimate partner violence: a community capacity approach. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2006;13:203–227. [Google Scholar]

- Malik NM, Ward K, Janczewski C. Coordinated community response to family violence: The role of domestic violence service organizations. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:933–955. doi: 10.1177/0886260508315121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D, Krueger R. The focus group kit. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publication; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Payne BK, Berg BL, James LDF. Attitudes about sanctioning elder abuse offenders among police chiefs, nursing home employees, and students. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2001;45:363–382. [Google Scholar]

- Podnieks E, Wilson S. Raising awareness of abuse of older persons: An issue for faith communities? Journal of Religion, Spirituality, & Aging. 2004;17:55–86. doi: 10.1300/J496v17no1_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riddell T, Ford-Gilboe M, Leipert B. Strategies used by rural women to stop, avoid, or escape from intimate partner violence. Health Care for Women International. 2009;30:134–159. doi: 10.1080/07399330802523774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto KA, Brossoie N, McPherson M, Pulsifer MB, Brown P. Violence against rural older women: Promoting community awareness and action. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2013;32:2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2012.00649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto KA, Teaster PB, McPherson MC, Mancini JA, Savla J. A community capacity framework for enhancing a criminal justice response to elder abuse. Journal of Crime and Justice. 2015;38(1):9–26. doi: 10.1080/0735648X.2013.804286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Perez I, Vives-Cases C, Escriba-Aguir V, Rodriguez-Barranco M, Nevot-Cordero A. How does intimate partner violence differ depending on level of rurality of residential area in Spain? Health & Social Work. 2015;40:108–119. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlv024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straka SM, Montminy L. Responding to the needs of older women experiencing domestic violence. Violence against women. 2006;12(3):251–267. doi: 10.1177/1077801206286221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publication; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Teaster PB, Dugar TA, Mendiondo MS, Abner EL, Cecil KA, Otto JM. The 2004 survey of state adult protective services: Abuse of adults 60 years of age and older. Washington, DC: The National Center on Elder Abuse; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Teaster PB, Roberto KA, Dugar T. Intimate partner violence of rural aging women. Family Relations. 2006;55(5):636–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00432.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tetterton S, Farnsworth E. Older women and intimate partner violence: Effective interventions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:2929–2942. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. State and county quick facts: Virginia. 2007 Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/

- Vinton L, Wilke DJ. Are collaborations enough? Professionals’ knowledge of victim services. Violence Against Women. 2014;20:716–729. doi: 10.1177/1077801214539857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Websdale N. Rural woman battering and the justice system: An ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Winick C. Maturing out of narcotic addiction. Bulletin of Narcotics. 1962;14:1–7. [Google Scholar]