Abstract

The food insecurity faced by many Native American communities has numerous implications for the health and welfare of families. To identify and address upstream causes of food insecurity in a rural California reservation, we conducted a community assessment using the Tool for Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments (THRIVE). Guided by a community-based participatory research orientation, the THRIVE tool was adapted using digital storytelling and implemented in a series of focus groups. As a result of the THRIVE assessment, community members identified racial injustice and physical and financial barriers to accessing healthy and culturally appropriate foods as areas of greatest importance. Subsequently, the project partnership developed policies to reduce identified barriers which included an integrated community supported agriculture and commodity food program, the introduction of Electronic Benefits Transfer and culturally appropriate foods at the local farmers’ market and reallocation of shelf space at the grocery store to include vegetables and fruits as well as special foods for diabetics. Results suggest that a participatory research orientation coupled with the use of a culturally adapted THRIVE tool may be an effective means for identifying structural determinants of food insecurity and initiating novel policy interventions to reduce health disparities experienced by Native American communities.

Introduction

Many Native American communities experience a lack of access to high quality and culturally appropriate foods. Food insecurity, defined as ‘having limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways’ [1], is a result of the underlying social, economic and institutional factors within a community that affect the quantity and quality of available food and its affordability or price relative to the financial resources available to acquire it [2, 3]. Such factors include supermarket flight, transportation barriers, the growth of fast-food chains and a lack of healthy foods sold at corner stores [4–9]. Food insecurity is also associated with fluctuations in funding for food assistance and other social safety net programs [10]. In some Native American reservations, over 85% of residents receive food assistance from the US Department of Agriculture's (USDA’s) Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR), typically consisting of canned and packaged foods that are high in salt, sugar and fat [11, 12]. Food insecurity has been studied primarily in urban areas where it is most prevalent in households with children, female-headed households and among African Americans and Latinos [13–15]. Few studies have examined food insecurity among Native Americans living on reservations [16–20].

The health consequences of food insecurity are well documented. Food insecure communities have higher rates of chronic disease related outcomes including obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease [13–15]. These outcomes are also highly prevalent among Native Americans, who have higher rates of obesity (24 versus 19%) and lower levels of leisure-time physical activity (33 versus 28%) than other race/ethnic groups combined [21]. The prevalence of diabetes among Native Americans is almost three times that of non-Hispanic whites of similar ages [21, 22]. Programs that have attempted to address these health disparities have typically been based on a medical model, which is clinical in nature and focused on individual weight loss and physical activity increases [23–26]. These programs have seen limited success.

We carried out the following community-based participatory research (CBPR) study with the Round Valley Indian Reservation community in Northern California to assess food insecurity within this community. Our project employed the Tool for Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments (THRIVE), a policy engagement framework developed by the Prevention Institute that helps communities “identify and foster elements and characteristics in the community environment that promote positive health and safety outcomes for racial and ethnic minorities’ [27, 28]. Action-oriented tools such as THRIVE are consistent with a participatory theoretical framework in that they seek to increase collective competence of communities and agencies to collaborate in identifying solutions by engaging community stakeholders in the identification of community needs and their root causes [29–31].

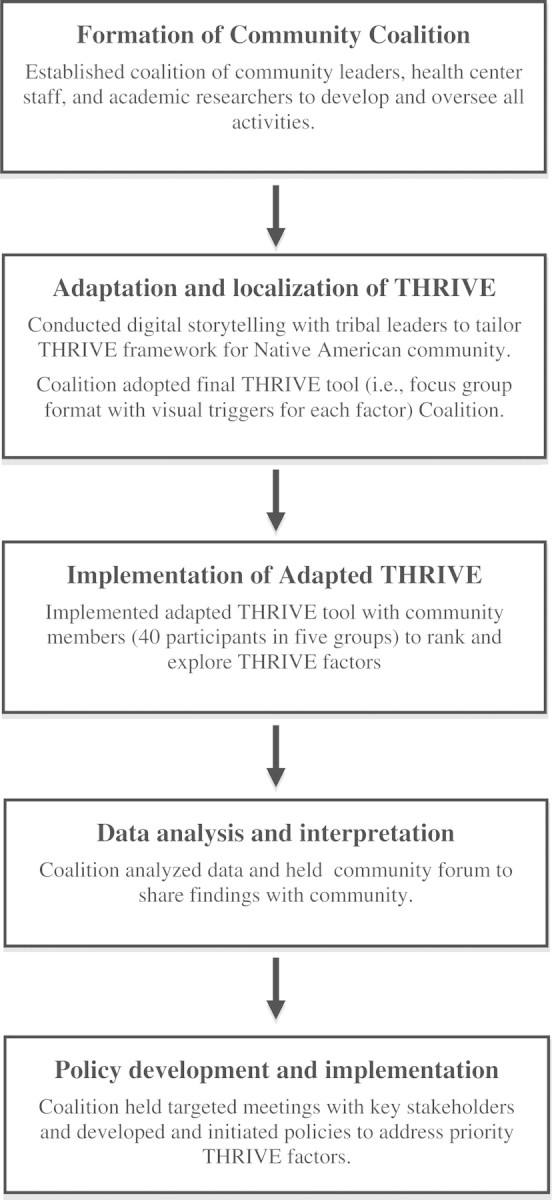

The main aims of this CBPR study were to: (i) identify community priority factors using the THRIVE assessment tool; (ii) link these priority factors to local community issues and (iii) design and implement policies related to the community issues. In this paper, we describe the cultural adaptation of the THRIVE tool, the results yielded from the THRIVE application as well as the policy alternatives developed by the partnership as a result of this process. An overview of this CBPR THRIVE assessment and policy development process is illustrated in Fig. 1. To our knowledge, no other study to date has employed THRIVE with a Native American community.

Fig. 1.

Overview of CBPR THRIVE assessment and policy development.

Methods

Community profile and food environment

The Round Valley community (referred to as Round Valley) is a geographically isolated community located within a dense mountain range in Mendocino County in Northern California. The Valley consists of approximately 4000 people living both on the Round Valley Indian reservation and the adjacent town of Covelo. The reservation was created in 1856 during the California gold rush when Native Americans from a number of local tribes were forced to relocate onto reservation land. Approximately 2000 people, or about half of the Valley’s population, are Native American and reside on the reservation. Educational and income levels in the Valley are low and unemployment is very high (52% for the Valley overall and 73% for Native American residents residing on the reservation). The Round Valley Indian Health Center, established in 1968, is the only source of health care in the Valley and offers primary health care services to all residents.

Surveys conducted by the Round Valley Indian Health Center, consistent with studies of Native Americans elsewhere [32–38], have found Native American community members to have low physical activity levels and diets that are nutritionally poor and high in fat and sugar. Of Native American residents aged 20–74 years, 68% are obese (Round Valley Indian Health Center survey, unpublished data), which is double the national average for all US adults (34%) [39]. Similarly, the rate of diabetes (11%) among the health center’s Native American adult patient population (Round Valley Indian Health Center survey, unpublished data) is much higher than the national average for all US adults of (<8%) [40].

The Valley has a single small local grocery store, located in the town of Covelo, in which approximately 85% of the shelf space is allocated to packaged foods (Round Valley Indian Health Center survey, unpublished data). A fast-food fried chicken establishment is located within the store. The only other place to purchase food in the Valley is a gas station, also located in the town of Covelo, which sells packaged snack foods and hot dogs. While a small farmers’ market does operate once a week in the town of Covelo, Native Americans in the Valley have reported in surveys administered by the Round Valley Indian Health Center that they do not shop at the farmer’s market because they do not feel welcome and because the cost of the produce is too high (Round Valley Indian Health Center survey, unpublished data). Ironically, two of the county’s largest organic farms are located in the Valley, but virtually, all of the produce from these farms is shipped out of the community, primarily to the San Francisco Bay area. About a third of Native American families in the Valley receive food from the FDPIR and nearly half of the food used for school meals at the Round Valley Unified School District comes from FDPIR [11].

CBPR orientation

This project used a CBPR orientation. CBPR offers an alternative to traditional research by placing the agenda and control of research in the hands of communities [41, 42]. This orientation has shown great promise for developing culturally relevant health interventions within Native American communities and tailoring successful programs for implementation across communities [43–53]. The following participatory research process was followed: (i) formation of a Community Coalition, (ii) adaptation and localization of the THRIVE framework using digital storytelling and Coalition recommendations, (iii) implementation of adapted THRIVE community focus groups and (iv) development of policy alternatives to address community priorities identified.

Formation of the Community Coalition

The formation of a Community Coalition (n = 10) composed of community leaders, Round Valley Indian Health Center staff, California Indian Health Service representatives and academic researchers was critical to the development of the project. Academic partners worked with Round Valley Indian Health Center staff, using snowball sampling to identify community leaders and stakeholders, both Native and non-Native. This group included members of the tribal council, Parent Teacher Association (PTA) and women’s and elder’s groups. Approximately, half of the coalition members were Native American and living on the reservation. At the onset of the project, coalition members discussed their roles and desired project outcomes. The primary author of this paper, a Native American researcher with expertise in CBPR and participatory media, initiated and led this process. Her participation facilitated a positive starting point of understanding and supported the goal of furthering tribal sovereignty. The project was reviewed and approved by the University of California Davis Institutional Review Board as well as the research committee of the tribal council and Round Valley Indian Health Center.

Adaptation and localization of THRIVE

The THRIVE policy engagement framework is designed to assist community members in identifying key social and environmental factors affecting health in their communities (Table I) [27, 28]. The tool is divided into three domains: (i) Equitable Opportunity, (ii) The People and (iii) The Place. Each domain is further divided into three to seven factors associated with health. Stakeholders are asked to rate the importance of each factor and then to respond to a number of related questions. The final stage of THRIVE is to engage stakeholders in actions to address identified policies and conditions contributing to health disparities. THRIVE can be accessed and completed online (http://thrive.preventioninstitute.org/thrive.html).

Table I.

THRIVE tool domains, factors and examples of adapted questions and digital story themes

| Domain | Factors | Example of adapted questions and digital story themes |

|---|---|---|

| Equitable Opportunity | Racial justice | Do people of all races and ethnicities have equal opportunity in our community? |

| Jobs and local ownership | Can people make a living wage in our community? | |

| Education | Does everyone in our community benefit from quality education and training? | |

| The People | Social networks and trust | Do people know and trust each other? |

| Participation and willingness to act for the common good | Is the community willing to take action to make things better? | |

| Acceptable behaviors and attitudes | Do members of the community expect and reinforce respectful, safe and health-promoting behaviors and attitudes? | |

| The Place | What's sold and how it's promoted | Are healthy products available and affordable in our community? |

| Look, feel and safety | Do we feel proud of our community? | |

| Parks and open space | Are there places where people can enjoy nature and be active in our community? | |

| Getting around | Can we affordably and efficiently get to where we need to be? | |

| Housing | Are there places we can afford to live in our community? | |

| Air, water and soil | Can I safely drink the water and breathe the air in my neighborhood? | |

| Arts and culture | Is expression through art honored and supported in my community? |

The Community Coalition determined that THRIVE needed to be adapted and tailored for cultural appropriateness. The THRIVE domains and factors, as well as the THRIVE rating system, could remain the same. However, the Coalition wanted to (i) use digital storytelling for local relevance and (ii) use focus groups to prioritize the THRIVE domains that resulted from the digital storytelling. A digital story is a short, first person video-narrative created by combining recorded voice, still and moving images and music or other sounds [54]. Based in the tradition of ‘photovoice’ and other participatory action methodologies, digital storytelling uses the power of the visual image and accompanying stories to create a participatory means of sharing expertise to create policy [55, 56]. Digital stories were created to accompany each THRIVE factor, illustrating the meaning of the factor and its manifestation in the local community context. Coalition members recommended that THRIVE be implemented in a focus group format rather than an online survey because focus groups provided community members with opportunities to discuss social and environmental factors affecting their health, identify strategies for policy change and build necessary support for change. Lastly, community members were asked to review and rate all of the THRIVE questions, of which food was only one part. The THRIVE tool was not modified to specifically address food insecurity on the reservation and the digital stories were not related solely to food insecurity.

The Native American members of the Coalition identified and invited additional Native American community leaders (n = 12) who participated in the digital storytelling component of this project. This group was composed of key stakeholders from various community groups, including the tribal council, PTA and women’s and elder’s groups and school administration. The Coalition members felt it was important to involve key leaders from these various stakeholder groups in this process of adapting and tailoring the intervention in order to raise awareness of the project and create community buy-in. The criterion for participation in the digital storytelling component of the project was identification by Native American Coalition members as a Native American community leader. Participants were provided compensation for their time and group meals were provided during the activities.

After receiving training on digital storytelling and THRIVE, digital storytelling participants used digital cameras to take still pictures and videos based on their interpretations of the THRIVE factors and how they experienced the factors in their community. After the digital stories were created, they were presented back to the group for further refinement, using the SHOWeD technique [57], which engages the group through a series of questions: (i) What do you see here? (ii) What’s really happening here? (iii) How does this relate to our lives? (iv) Why does this problem, concern or strength exist? and (v) What can we do about it? The group then selected the digital stories they felt were most appropriate to be used as visual triggers to facilitate dialogue in the THRIVE focus groups. The stories were reviewed by Coalition members and incorporated into a THRIVE focus group guide (Table I). As an example of the process, the THRIVE factor ‘what’s sold and how it’s promoted’ was accompanied by a digital story about the local grocery store, showing the lack of shelf space dedicated to fresh produce, the wilted and poor quality produce in the local grocery store and other such images. The process allowed the THRIVE factor to be interpreted and represented by community members for discussion.

Implementation of community focus groups

The subsequent THRIVE focus groups were carried out with the goal of identifying the THRIVE domains of greatest importance to the community. Five focus groups were conducted (n = 40 total participants) with patients at the health center, parents and teachers from the PTA, the elders group and small business owners. Members of the Coalition and participants in the digital storytelling process used snowball and convenience sampling to identify focus group participants. Both Native and non-Native American community members were invited to participate, with 31 of the 40 participants identifying as Native American. Each focus group contained eight participants. The Native American academic partner conducted training in leading focus groups with two Native American Coalition members, who then led the five focus groups. The Coalition members advised against video or audio recording the focus groups because of the historic distrust of research within the community and the concern that, in such a small community, sensitive information may be shared. Thus, one of the focus group leaders took notes while the other leader facilitated the questions and discussions.

Participants rated the thirteen THRIVE factors in terms of how much of a priority the factor was for their community (high, medium and low). Participants also assigned a community effectiveness score for each factor to measure how effective the community was at fostering each THRIVE factor. To obtain this score, a five-point scale was used to rate the community's effectiveness, with a level one rating meaning that elements are not in place and the community lacks capacity in that area and a level five rating meaning that the elements are in place to meet the range of developmental needs, are culturally appropriate, accessible and available to the community [28].

Data analysis

The goal of the data analysis was to identify priority THRIVE factors and community effectiveness scores as well as to learn how these specific factors manifested in Round Valley. The focus group data were analyzed, using summative content analysis, by Coalition academic partners using NVivo software (version 7) [58]. The THRIVE tool ratings were analyzed by the Coalition Indian Health Service partners, who volunteered the staff time of an epidemiologist to complete the descriptive statistical analysis using SPSS (version 16). Both members of the Coalition and the participants in the digital storytelling process, who were interested to learn how their digital stories had contributed to the community discussion, reviewed the findings. Findings were triangulated and presented back to focus group participants and open to the entire community in a ‘town hall’ style meeting held at the Round Valley Indian Health Center.

Results

Focus group THRIVE priority factors and how they manifested in the community

The focus groups found that ‘racial justice’ was the issue in the community of greatest importance, rated ‘high’ in priority by 27 of the 40 focus group participants and discussed at length in all five of the focus groups. As one focus group participant stated, ‘There are two worlds here, and no one talks about it because if we did we would never be able to live side-by-side like this’. However, when using the THRIVE priority ratings to determine which factors to take action on, participants in all five focus groups expressed that the issue of racial justice was overwhelming and somewhat abstract and that the community was not ready or able to address racial justice directly. Instead, THRIVE priority ratings identified three additional factors, all determined to be interrelated and indirectly impacting racial justice, which were selected by 29 of the 40 focus group participants as top priorities for action steps: (i) ‘jobs and local ownership’; (ii) what’s sold and how it’s promoted and (iii) look, feel and safety (Table II). These factors were all given poor community effectiveness scores (mean ranking of 2) and were rated as the top three priorities in all five of the focus groups.

Table II.

Focus group priority factors and how they manifested in the community and related polices implemented

| Priority THRIVE factors | How these factors manifested in the community | Policies implemented |

|---|---|---|

| Jobs and local ownership | Local growers ship nearly all fresh produce out of the valley to higher income and urban areas | Local growers formed Producers’ Guild (n = 32) |

| Growers have no financial incentive to keep produce local due to poor economy in the community | Community Coalition developed a CSA program that keeps local produce in the community and guarantees growers payment for unused food | |

| Only one Native-owned business in the community—a recycling stand | Pilot program started to increase vegetable and fruit intake in fifth grade class using CSA produce. Program provides 25% of families receiving commodity foods with supplemental fresh vegetables and fruit using CSA produce | |

| Native community members feel unwelcome at farmer’s market and are unable to pay for fresh produce | Community Coalition negotiated with farmer’s market vendors to provide EBT machines. Community members can purchase fresh produce using food assistance funds | |

| What’s sold and how it’s promoted | Little to no quality, culturally appropriate and traditional food available. Special dietary foods available at the only grocery store in the community | Shelf space at grocery store reallocated to include and promote fresh vegetables and fruits |

| No inexpensive bulk food available | Special order and bulk order program initiated to provide traditional and special foods for diabetics | |

| Look, feel and safety | Community has no playgrounds or parks and few safe places to exercise | Community Coalition designed a walking and bike path with culturally appropriate art and educational exhibits |

| Local health clinic created ‘Bike Wednesdays’ that include free bike repair and group rides |

When discussing ‘jobs and ownership’ participants talked about the lack of Native-owned businesses in the Valley (e.g. a small recycling station is the only known Native-owned enterprise in the valley). They pointed out that the absence of Native-owned stands at the weekly farmers’ market as well as its location in a mostly white area of town made Native people feel unwelcome. Cash-only sales at the farmers’ market were cited as an additional barrier for Native community members in accessing food at the market.

Closely related were issues regarding ‘what’s sold and how it’s promoted’. Community members pointed out that without a job or a living wage, it was difficult paying for the gas needed to travel 2 hours to the closest supermarket. As a result, Native American residents relied almost exclusively on the packaged foods from the local grocery store or on the canned goods from the USDA FDPIR program. The local grocery store had little to no quality and culturally appropriate and traditional foods; bulk and special dietary foods were entirely unavailable. The available foods were overpriced. Commodity foods consisted of canned goods high in fat, sugar and salt and low in fiber. Focus group participants reported that a favorite snack for the youth was gravy because it could easily be made from the large quantities of flour and lard in the USDA FDPIR food packages.

Focus group members felt that the factor ‘look, feel and safety’ played out in their community in its absence of playgrounds, parks, sidewalks and streetlights. They felt that the lack of such infrastructure made the community members feel unsafe and embarrassed of their community and made physical activity difficult to engage in.

Policies developed and implemented

Over the course of one year, following the THRIVE process and analysis of data, the Coalition held a series of meetings with key stakeholders including owners of the farms, grocery store and gas station. The goal of these meetings was to share and discuss THRIVE results and to identify policies to address the three factors identified by the community as priorities for action. The Coalition created presentations for these meetings using focus group data, images from the digital stories and local health statistics (e.g. obesity and diabetes rates). Community members participated in these meetings and shared accounts of their difficulty accessing healthy foods or having a voice in issues affecting jobs and local ownership in their community.

As a result of the THRIVE assessment and stakeholder meetings, the Coalition proposed a number of policy changes (Table II). To address ‘jobs and local ownership’, a Producer’s Guild was established to bring together the agricultural producers in the Valley with the Community Coalition members and other key stakeholders to develop relationships, assess the producers’ needs and ultimately develop a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program for the Valley. After a year of working with the Producers’ Guild, a CSA was established so that a portion of local produce would be set aside for sale in the local community and local growers would be guaranteed payment for any unsold produce [59]. The development and organization of the Producers’ Guild and subsequent CSA program created several new training and job opportunities in the Valley. The Round Valley Indian Health Center pledged funding for a pilot program to use CSA produce for Round Valley Unified School District school lunches. The Round Valley Indian Health Center also obtained funding for a program to supply CSA produce through the UDSA FDPIR commodity food distributions on the reservation; through this pilot program, approximately, 25% of families receiving commodity foods received additional local produce. Additionally, the Coalition successfully lobbied for portable Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) machines to be made available at the farmers’ market, allowing residents to use their food assistance funds to purchase fresh produce at the market.

To address ‘what’s sold and how it’s promoted’, the Coalition worked with the local grocery store to change the shelf-space allocation to include and promote fresh vegetables and fruits. Special order and bulk order programs were initiated to provide traditional and special foods for diabetics.

To address look, feel and safety, the tribal council and the health clinic wrote a grant to create a place for Native community members to engage in physical activity. The proposed walking and bike path, to include culturally appropriate art and educational exhibits designed by Native American community members, is in the planning stages. Additionally, the clinic created ‘Bike Wednesdays’ featuring group rides and free bike repair.

Discussion

In this CBPR study, we adapted and implemented THRIVE in a Northern California Native American reservation community. Through the use of a participatory framework, community stakeholders identified and addressed upstream determinants of food insecurity. While a number of previous studies have attempted to reduce obesity and diabetes among Native Americans through individual-level behavior change [23, 24, 60, 61], this study is one of few to date that aimed to address Native American health disparities through examining determinants of Native American food insecurity and changing the reservation food environment. Similar to previous studies that have examined barriers to healthy eating among Native Americans living on reservations [12, 62], our study uncovered numerous structural and environmental barriers to healthy eating and physical activity. Geographic isolation, extremely limited access to fresh produce, poverty and structural barriers to physical activity were prevalent in the reservation.

Through an intensive process of engaging the community and a range of stakeholders in identifying priority determinants for change, the project was successful in developing a number of viable policy alternatives and interventions to promote health and wellness in the Valley. The establishment of the Community Coalition was critical to the success of this project. Coalition members, who were selected because of their long-term engagement with and commitment to the community, provided a rich array of resources and expertise to the project. Committed to creating sustainable change for the valley community, these coalition members were crucial in engaging community stakeholders, such a farm and store owners, in intervention efforts. Furthermore, Coalition members obtained funding for a number of novel interventions such as the incorporating of CSA produce into the commodity food distribution.

The use of the THRIVE tool, a framework which focuses on upstream causes of health disparities, was effective in moving the Coalition and community members past a traditional, individually focused analysis of community health and wellness. Adaptation of this tool, through the incorporation of digital stories created by community members, illustrated THRIVE factors as they played out in the Valley and was essential in localizing and adapting the tool for implementation. Focus group discussions allowed community members to tell their stories and resulted in a more relevant instrument through which to identify and address community health disparities. This adapted and more participatory process permitted community members to discuss the challenging and rarely openly discussed issues affecting their community, such as racial justice. While focus group findings showed low community readiness to address this important factor directly, the interconnectedness of this factor to the other three prioritized factors—jobs and local ownership, what’s sold and how it’s promoted and look, feel and safety—led to a number of projects likely to have implications for addressing racial justice, including increasing access to fresh vegetables and fruits, promoting jobs and local ownership for Native people and supporting tribal sovereignty. The specific policies discussed within this article are currently in various implementation and evaluation stages, including the increased allocation of shelf space at the local grocery store and the implementation of EBT payments at the farmers’ market. Assessments of the effects of these policies on vegetable and fruit consumption are underway. The efficacy of the CSA pilot programs to increase vegetable and fruit intake among fifth graders and commodity food recipients is also being evaluated. The findings of these evaluations will guide the Community Coalition members, including tribal leadership and health center leaders, in further refining policy, system and environmental level strategies to reduce food insecurity.

In conclusion, CBPR, coupled with the evidence-based, theory driven THRIVE model, was effective in engaging this Native American reservation community in a process of identifying and addressing upstream factors impacting their health and well-being. This process resulted in the successful translation of research into practice and built the capacity of community members and academic partners alike.

Funding

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation New Connections Active Living Research program; California Endowment; California Department of Transportation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our gratitude to the Community Coalition members Beverly Calderon, Steve Viramontes, Rose Francia, Anna Fries, Diann Simmons and the residents of the Round Valley Indian reservation community.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Anderson SA. Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. J. Nutr. 1990;120(11 Suppl):1555–600. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.suppl_11.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breckwich Vasquez V, Lanza D, Hennessey-Lavery S, et al. Addressing food security through public policy action in a community-based participatory research partnership. Health Promot Pract. 2007;8:342–9. doi: 10.1177/1524839906298501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen B. Community Food Security Assessment Toolkit (E-FAN-02–013) Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drewnowski A. Obesity and the food environment: dietary energy density and diet costs. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3 Suppl):154–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill J. Obesity and the Built Environment: Improving Public Health Through Community Design; 2004 May 24–26. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health Conference; 2004. Addressing the environment to reduce obesity. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drewnowski A, Specter SE. Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:6–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galvez MP, Frieden TR, Landrigan PJ. Obesity in the 21st century. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:A684–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.111-a684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dannenberg AL, Jackson RJ, Frumkin H, et al. The impact of community design and land-use choices on public health: a scientific research agenda. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1500–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, et al. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:23–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook JT. Clinical implications of household food security: definitions, monitoring, and policy. Nutr Clin Care. 2002;5:152–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5408.2002.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris S, Harper BL. Lifestyles, diets, and Native American exposure factors related to possible lead exposures and toxicity. Environ Res. 2001;86:140–8. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burhansstipanov L. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2001. Cancer: a growing problem among American Indians and Alaska Natives. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cade J, Upmeier H, Calvert C, et al. Cost of a healthy diet: analysis from the 1K Women's Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr. 1999;2:505–12. doi: 10.1017/s1368980099000683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morland K, Wing S, Roux AD. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents' diets: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1761–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swinburn BA, Caterson I, Seidell JC, et al. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:123–46. doi: 10.1079/phn2003585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gittelsohn J, Toporoff EG, Story M, et al. Food perceptions and dietary behavior of American-Indian children, their caregivers, and educators: formative assessment findings from pathways. J Nutr Educ. 2000;32:2–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3182(00)70504-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham-Sabo L, Snyder MP, Anliker J, et al. Impact of the Pathways food service intervention on breakfast served in American-Indian schools. Prev Med. 2003;37(Suppl. 1):S46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curran S, Gittelsohn J, Anliker J, et al. Process evaluation of a store-based environmental obesity intervention on two American Indian reservations. Health Educ Res. 2005;20:719–29. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gittelsohn J, Anliker JA, Sharma S, et al. Psychosocial determinants of food purchasing and preparation in American Indian households. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2006;38:163–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gittelsohn J, Sharma S. Physical, consumer, and social aspects of measuring the food environment among diverse low-income populations. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4 Suppl. 1):S161–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jernigan VBB, Duran B, Ahn D, et al. Changing patterns in health behaviors and risk factors related to cardiovascular disease Among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:677–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.164285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burrows NR, Geiss LS, Engelgau MM, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among Native Americans and Alaska Natives, 1990–1997: an increasing burden. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1786–90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.12.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilliland SS, Azen SP, Perez GE, et al. Strong in body and spirit: lifestyle intervention for Native American adults with diabetes in New Mexico. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:78–83. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin JA, Gilliland SS, Perez G, et al. Participant satisfaction with a culturally appropriate diabetes education program: the Native American Diabetes Project. Diabetes Educ. 1999;25:351–63. doi: 10.1177/014572179902500306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, et al. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;290:1884–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narayan KM, Gregg EW, Fagot-Campagna A, et al. Diabetes–a common, growing, serious, costly, and potentially preventable public health problem. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;50(Suppl. 2):S77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis R, Cook D, Cohen L. A community resilience approach to reducing ethnic and racial disparities in health. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:2168–73. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute P. Thrive TOOL. Oakland, CA: Prevention Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eng E. Action-oriented community diagnosis: a health education tool. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1990;11:93–110. doi: 10.2190/W8MU-5H9X-PQW1-LV38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorensen G, Emmons K, Hunt MK, et al. Implications of the results of community intervention trials. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:379–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teufel NI, Dufour DL. Patterns of food use and nutrient intake of obese and non-obese Hualapai Indian women of Arizona. J Am Diet Assoc. 1990;90:1229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown AC, Brenton B. Dietary survey of Hopi Native American elementary students. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94:517–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russell ME, Weiss KM, Buchanan AV, et al. Plasma lipids and diet of the Mvskoke Indians. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:847–52. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.4.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Story M, Tompkins RA, Bass MA, et al. Anthropometric measurements and dietary intakes of Cherokee Indian teenagers in North Carolina. J Am Diet Assoc. 1986;86:1555–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Story M, Strauss KF, Zephier E, et al. Nutritional concerns in American Indian and Alaska Native children: transitions and future directions. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98:170–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Story M, Evans M, Fabsitz RR, et al. The epidemic of obesity in American Indian communities and the need for childhood obesity-prevention programs. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(4 Suppl):747S–54S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.747S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravussin E, Valencia ME, Esparza J, et al. Effects of a traditional lifestyle on obesity in Pima Indians. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1067–74. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.9.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US Adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the U.S. population. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1263–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Community Health Scholars Program. Community Health Scholars Program Spring Networking Meeting; 2001 June. Anne Arbor, MI: Community Health Scholars Program; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohatt G, Hazel K, Allen J, et al. Unheard Alaska: culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;33:263–73. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027011.12346.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santiago-Rivera A, Skawennio Morse G, Hunt A, et al. Building a community-based research partnership: lessons from the Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne. J Community Psychol. 1998;26:163–74. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ellis B. Mobilizing communities to reduce substance abuse in Indian Country. In: Nebelkopf E, Phillips M, editors. Healing and Mental Health for Native Americans: Speaking in Red. New York, NY: Altamira Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Severtson DJ, Baumann LC, Will JA. A participatory assessment of environmental health concerns in an Ojibwa community. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19:47–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lantz P, Orians C, Liebow E, et al. Implementing women's cancer screening programs in American Indian and Alaska Native populations. Health Care Women Int. 2003;24:674–96. doi: 10.1080/07399330390227481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis SM, Reid R. Practicing participatory research in American Indian communities. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:755S–9S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.755S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Satterfield DW, Volansky M, Caspersen CJ, et al. Community-based lifestyle interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2643–52. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fisher PA, Ball T. The Indian Family Wellness project: an application of the tribal participatory research model. Prev Sci. 2002;3:235–40. doi: 10.1023/a:1019950818048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fisher PA, Ball T. Tribal participatory research: mechanisms of a collaborative model. Am J Community Psychol. 2003;32:207–16. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000004742.39858.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jumper-Thurman P, Plested B, Edwards R, et al. Community readiness: the journey to community healing. In: Nebelkopf E, Phillips M, editors. Healing and Mental Health for Native Americans: Speaking in Red. New York, NY: Altamira Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jernigan VBB. Community-based participatory research with Native American communities: the chronic disease self-management program. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11:888–99. doi: 10.1177/1524839909333374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gubrium A. Digital storytelling: an emergent method for health promotion research and practice. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10:186–91. doi: 10.1177/1524839909332600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catalani C, Minkler M. Photovoice: a review of the literature in health and public health. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37:424–51. doi: 10.1177/1090198109342084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chavez V, Israel B, Allen A, et al. A bridge between communities: video-making using principles of community-based participatory research. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5:395–403. doi: 10.1177/1524839903258067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shaffer R. Beyond the Dispensary. Nairobi, Kenya: African Medical and Research Foundation; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sorensen A. NVivo 7 by QSR International. J Mixed Method Res. 2008;2:106. [Google Scholar]

- 59.US Department of Agriculture. Alternative Farming Systems Information Center. Washington, DC: National Agricultural Library; Community supported agriculture. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Narayan KM, Hoskin M, Kozak D, et al. Randomized clinical trial of lifestyle interventions in Pima Indians: a pilot study. Diabetes Med. 1998;15:66–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199801)15:1<66::AID-DIA515>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roubideaux Y. Perspectives on American Indian health. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1401–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]