ABSTRACT

In order to optimize interactions with their environment and one another, bacteria regulate their motility. In the case of the rod-shaped cells of Myxococcus xanthus, regulated motility is essential for social behaviors. M. xanthus moves over surfaces using type IV pilus-dependent motility and gliding motility. These two motility systems are coordinated by a protein module that controls cell polarity and consists of three polarly localized proteins, the small G protein MglA, the cognate MglA GTPase-activating protein MglB, and the response regulator RomR. Cellular reversals are induced by the Frz chemosensory system, and the output response regulator of this system, FrzZ, interfaces with the MglA/MglB/RomR module to invert cell polarity. Using a computational approach, we identify a paralog of MglB, MXAN_5770 (MglC). Genetic epistasis experiments demonstrate that MglC functions in the same pathway as MglA, MglB, RomR, and FrzZ and is important for regulating cellular reversals. Like MglB, MglC localizes to the cell poles asymmetrically and with a large cluster at the lagging pole. Correct polar localization of MglC depends on RomR and MglB. Consistently, MglC interacts directly with MglB and the C-terminal output domain of RomR, and we identified a surface of MglC that is necessary for the interaction with MglB and for MglC function. Together, our findings identify an additional member of the M. xanthus polarity module involved in regulating motility and demonstrate how gene duplication followed by functional divergence can add a layer of control to the complex cellular processes of motility and motility regulation.

IMPORTANCE Gene duplication and the subsequent divergence of the duplicated genes are important evolutionary mechanisms for increasing both biological complexity and regulation of biological processes. The bacterium Myxococcus xanthus is a soil bacterium with an unusually large genome that carries out several social processes, including predation of other bacterial species and formation of multicellular, spore-filled fruiting bodies. One feature of the large M. xanthus genome is that it contains many gene duplications. Here, we compare the products of one example of gene duplication and divergence, in which a paralog of the cognate MglA GTPase-activating protein MglB has acquired a different and opposing role in the regulation of cellular polarity and motility, processes critical to the bacterium's social behaviors.

INTRODUCTION

For the Gram-negative soil bacterium Myxococcus xanthus, motility and its regulation are essential for a variety of social behaviors, including the coordinated spreading of colonies in the presence of nutrients, predation, and the formation of spore-filled, multicellular fruiting bodies in the absence of nutrients (1). The rod-shaped cells of M. xanthus move across surfaces in the direction of their long axis and, thus, have a defined leading and lagging cell pole. Cell movements are powered by two distinct yet coregulated motility systems (2). Type IV pilus (T4P)-dependent motility is cell-cell contact dependent and is driven by the retraction of T4P located at the leading cell pole (3, 4), whereas gliding motility allows individual cells to move across surfaces. Although characterization of the gliding motility motor is ongoing, current research supports a model in which multiprotein complexes assemble at the leading cell pole, remain stationary with respect to the substratum as a cell moves forward, and disassemble as they reach the lagging cell pole (5–11). These complexes either span the cell envelope, creating contact points where a cell generates traction force (7–9, 11, 12), or alternatively distort the cell envelope to generate force powering cell movement (13, 14).

In order to coordinate movement between cells or appropriately react to the environment, M. xanthus cells occasionally stop and reverse their direction of movement (15). The Frz chemosensory system regulates the reversal frequency, and this regulation is essential for social behaviors in M. xanthus (15–17). During a reversal, cells switch polarity; the old leading pole becomes the new lagging cell pole, and the two motility systems switch polarity accordingly (18–20). Many components of the Frz system are homologous to those of the Che system involved in regulating flagellar rotation in flagellated bacteria (21). However, unlike the Che system, in which the output response regulator CheY interacts directly with the flagellar motor (22), the output response regulator FrzZ of the Frz system does not interface directly with the motility motors but rather acts indirectly by controlling the localization of the proteins necessary for establishing and maintaining the dynamic polarity of the two motility systems (23).

The protein module that regulates polarity of the two motility systems in M. xanthus consists of the small Ras-like G protein MglA, its cognate GTPase-activating protein (GAP) MglB, and the response regulator RomR (24–27). MglA in the active GTP-bound form is primarily localized to the leading cell pole, while the inactive GDP-bound form is diffusely located throughout the cytoplasm (25, 26, 28), although recent work suggests that MglA-GTP may also form a gradient within the cell that is highest at the leading cell pole (29). Both MglB and RomR are primarily located at the lagging cell pole, with only lower quantities at the leading cell pole (25, 26, 30). All three proteins interact directly and are mutually dependent for their appropriate asymmetric localization (24–27, 31). RomR has been suggested to act as the link between the Frz chemosensory system and the MglA/MglB/RomR module. Specifically, it has been hypothesized that Frz signaling results in phosphorylation of the receiver domain in RomR (24, 30). Then, by an unknown mechanism, RomR phosphorylation causes the polar release of the three proteins followed by their redistribution to the opposite cell poles.

Among the three proteins in the polarity module and the Frz system, MglA is essential for cellular motility, and lack of RomR causes significant motility defects (24, 27, 30). MglA stimulates the formation of the gliding motility complexes at the leading cell pole and remains associated with these complexes as they move toward the lagging cell pole (10, 26, 32). MglA also stimulates T4P activity at the leading cell pole by regulating the correct polar localization of the two ATPases required for T4P function, PilB and PilT, although the mechanism is still unknown (25, 33). In contrast, MglB and Frz are not required for motility per se but for proper regulation of the reversal frequency (15, 24, 27).

Here, we explore the role of a previously uncharacterized MglB homolog, MglC (MXAN_5770), in motility regulation in M. xanthus. We demonstrate that MglC regulates cellular reversals and interacts directly with the polarity module proteins RomR and MglB. Interestingly, despite its homology to MglB, MglC plays an opposite role in regulating cellular reversals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Software and settings.

Multiple-sequence alignments were built using the L-INS-i algorithm of the MAFFT version 6.717b software package (34). Phylogenetic trees were built with FastTree version 2.1.3 (35) using the slow option. Relevant data were mapped onto phylogenetic trees using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) tool (36). Sequence logos of the positions shared between a multiple alignment of coupled and orphan MglB sequences were constructed using WebLogo version 3 (37). The MglC homology model was built by the Phyre2 web server (38) using the intensive option. Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with the UCSF Chimera package version 1.10.1 (39). Chimera was developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by NIGMS P41-GM103311).

Strains, strain construction, and cultivation.

Plasmids were propagated in Escherichia coli TOP10 [F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ϕ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7679 galU galK rpsL endA1 nupG] unless otherwise stated. E. coli cells were grown in LB or on plates containing LB supplemented with 1.5% agar at 37°C, with added antibiotics if appropriate (40). All M. xanthus strains are derivatives of the laboratory strain DK1622, the wild-type (WT) strain for this study (4). All DNA fragments generated by PCR were verified by sequencing. All M. xanthus strains constructed were confirmed by PCR. The M. xanthus strains and the plasmids used in this work are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Cells were routinely grown in 1% Casitone (CTT) medium or on CTT agar (CTT containing 1.5% agar) at 32°C (44). Kanamycin (50 μg/ml) or oxytetracycline (10 μg/ml) was added when appropriate. The in-frame deletion mutation of mglC was created as described previously using plasmid pAM1 (45). Other plasmids were integrated by site-specific recombination at the Mx8 attB site (46, 47). The plasmids created for this work were generated with the primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

TABLE 1.

M. xanthus strains used in this work

| Strain | Relevant genotypea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| DK1622 | WT | 4 |

| SA4420 | ΔmglA | 25 |

| SA3387 | ΔmglB | 25 |

| SA3985 | ΔfrzZ | 24 |

| SA3300 | ΔromR | 24 |

| SA7300 | ΔmglC | This work |

| SA7301 | ΔmglA ΔmglC | This work |

| SA7302 | ΔmglB ΔmglC | This work |

| SA7303 | ΔfrzZ ΔmglC | This work |

| SA7304 | ΔromR ΔmglC | This work |

| SA7305 | ΔmglC attBΩppilA-mglC (pAM5) | This work |

| SA7306 | ΔmglC attBΩppilA-YFP-mglC (pAM10) | This work |

| SA7307 | ΔmglA ΔmglC attBΩppilA-YFP-mglC (pAM10) | This work |

| SA7308 | ΔmglB ΔmglC attBΩppilA-YFP-mglC (pAM10) | This work |

| SA6303 | ΔromR ΔmglC attBΩppilA-YFP-mglC (pAM10) | This work |

| SA7310 | ΔmglC attBΩppilA-mglCF25A D26A I28A (pMH11) | This work |

| SA7314 | ΔmglC attBΩppilA-YFP-mglCF25A D26A I28A (pMH12) | This work |

Plasmids listed in parentheses were integrated at the Mx8 attB site.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this work

| Plasmid | Use and/or relevant characteristic(s) (plasmid of origin) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pBJ114 | In-frame deletion vector, kan | 41 |

| pSW105 | Complementation from attB with ppilA kan | 42 |

| pSL60 | attP ppilA-YFP-mglA kan | 25 |

| pAM1 | To create in-frame deletion of mglC (pBJ114) | This work |

| pAM5 | attP ppilA-mglC kan (pSW105) | This work |

| pAM10 | attP ppilA-YFP-mglC kan (pSL60) | This work |

| pMH11 | attP ppilA-mglCF25A D26A I28A kan (pSW105) | This work |

| pMH12 | attP ppilA-YFP-mglCF25A D26A I28A kan (pSL60) | This work |

| pTM1 | MglA-His6 overexpression (pET28a) | 26 |

| pTM2 | His6-MglB overexpression (pET28a) | 26 |

| pAM15 | His6-MglC overexpression (pET28c) | This work |

| pUT18c | Empty vector, T18 cyaA fragment, bla | 43 |

| pKNT25 | Empty vector, T25 cyaA fragment, kan | 43 |

| pDK53 | FrzZ (pKNT25) | This work |

| pDK61 | FrzZ (pUT18C) | This work |

| pDK70 | MglA (pKNT25) | This work |

| pDK71 | MglB (pKNT25) | This work |

| pDK74 | MglB (pUT18C) | This work |

| pDK75 | MglA (pUT18C) | This work |

| pDK110 | RomR C-terminal Glu-rich region (pKNT25) | This work |

| pDK111 | RomR C-terminal Glu-rich region (pUT18C) | This work |

| pDK114 | RomR N-terminal receiver (pKNT25) | This work |

| pDK119 | RomR N-terminal receiver (pUT18C) | This work |

| pDK126 | RomR Pro-rich linker (pKNT25) | This work |

| pDK127 | RomR Pro-rich linker (pUT18C) | This work |

| pDK136 | MglC (pUT18C) | This work |

| pDK137 | MglC (pKNT25) | This work |

| pMH6 | MglCF25A D26A I28A (pKNT25) | This work |

Assays for gliding motility, type IV pilus-dependent motility, and cellular reversal frequency.

Motility assays were performed as described by Keilberg et al. (24). For reversal frequency assays, cells were grown in CTT overnight and adjusted to an optical density at 550 nm (OD550) of 7; then, 5 μl was spotted onto agar pads (1.5% agar, 0.5% Casitone, 10 mM Tris, 8 mM MgSO4, 1 mM KPO4, pH 7.6), mounted on glass slides, incubated 16 h at 32°C, and covered with a coverslip. Images were captured every 30 s for 15 min; then, individual cells were selected at random, and cellular reversals were tallied for the selected cells.

Fluorescence microscopy.

Fluorescence microscopy was carried out as described previously (25). For time-lapse microscopy, cells were placed on thin 1.5% agar pads buffered with TPM (10 mM Tris, 8 mM MgSO4, 1 mM KPO4, pH 7.6) and imaged every 30 s for 15 min, and images were captured and analyzed with Metamorph (Molecular Devices, Inc.).

Bacterial two-hybrid analysis.

Plasmids listed in Table 2 were transformed pairwise into chemically competent E. coli BTH101 cells [F− cya-99 araD139 galE15 galK16 rpsL1 (Strr) hsdR2 mcrA1 mcrB1] (Euromedex, France), and after recovery, cells were plated on LB plates containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin, 30 μg/ml kanamycin, 1 mM isopropyl-β–d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and 40 μg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal). Plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 h, and then randomly selected individual colonies were suspended in 50 μl LB, and 5 μl were spotted onto fresh LB ampicillin-kanamycin-IPTG-X-gal plates and incubated for 48 h at 30°C prior to imaging.

Protein purification.

Plasmids pTM1, pTM2, and pAM15 were transformed into E. coli Rosetta [F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm(pRARE2)] (Novagen). His6-tagged MglB, MglA, and MglC were expressed and affinity purified as described previously using an Ni2+ resin (Macherey-Nagel) (24–26).

GTPase assay.

[γ-32P] GTP hydrolysis reactions were carried out with 2 μM (final concentration) each of the purified proteins at 37°C in phosphate buffer (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaPO4), as described previously (48). After activated charcoal quenching, the free 32P in the resulting supernatant was measured with a scintillation counter (LS6500; Beckman Coulter).

RESULTS

M. xanthus has an orphan paralog, MglC, of the GAP MglB.

A recent computational analysis of 1,609 prokaryotic genomes identified homologs of MglA and MglB in many of these genomes (49). This analysis also revealed that there are five distinct groups (MglA_1 to MglA_5) within the MglA family and that MglA of M. xanthus is a member of group 1. Moreover, most mglA genes (390 of 449) are located within four genes of an mglB gene, which we will refer to here as coupled mglA and mglB genes. Phylogenetic analysis also demonstrated that coupled mglA and mglB genes have coevolved. Although most mglA genes are coupled to an mglB gene, only 421 of 749 mglB genes identified, in contrast, are genetically coupled to an mglA gene. The difference in numbers between coupled mglB and mglA genes is due to a subset of the mglA genes that are coupled to two mglB genes (49). However, 328 mglB genes are not coupled to an mglA gene, and we refer to these mglB genes as orphans.

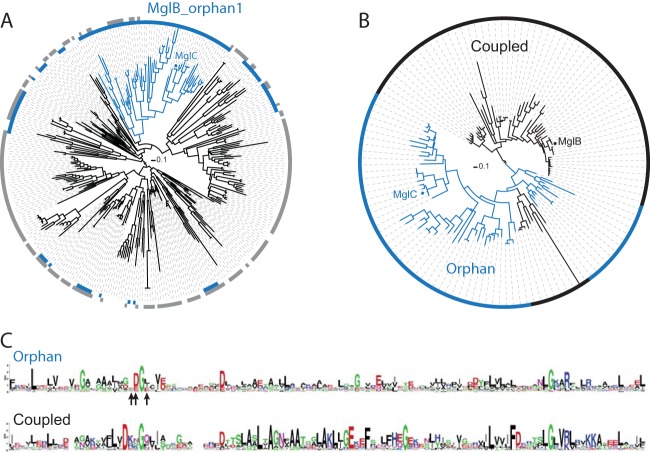

We performed a phylogenetic analysis of all 328 orphan MglB family members and found that there is a distinct subfamily of orphan MglB sequences (MglB_orphan1) that are found in genomes that all encode a member of the MglA_1 group (Fig. 1A). Among the 59 members of the MglB_orphan1 subfamily, we identified one encoded by the M. xanthus genome, MXAN_5770, here referred to as MglC. We constructed a phylogenetic tree from a multiple-sequence alignment of the newly identified MglB_orphan1 sequences and those MglB sequences (MglB_coupled1) that are genetically coupled to an MglA_1 group member (49) (Fig. 1B). We identified two distinct clades in this tree. One clade (n = 60 sequences) is composed entirely of sequences from the MglB_coupled1 group, including MglB from M. xanthus, whereas the second clade (n = 68 sequences) is primarily composed of MglB_orphan1 sequences, including MglC. In this analysis, nine MglB_coupled1 sequences are present in the predominantly orphan clade. Seven of these nine MglB_coupled1 sequences are cases where two mglB sequences are genomically coupled to an mglA_1 group sequence, with one mglB sequence in the coupled clade and the other in the orphan clade. This pattern supports the ideas that MglB and MglC are the result of a gene duplication event and that both members may play a role in group 1 MglA/MglB systems.

FIG 1.

MglC is an orphan homolog of MglB. (A) Identification of the MglB_orphan1 subfamily. A phylogenetic tree was constructed from a multiple-sequence alignment of 328 orphan MglB sequences identified in a previous study (46). The innermost ring around the tree (blue) shows the sequences encoded in genomes that also encode group 1 MglA sequences, and the ring in gray shows the sequences encoded in genomes that encode group 2, 3, 4, or 5 MglA sequences. The blue branches identify the conserved MglB_orphan1 clade. (B) A phylogenetic tree built from a multiple-sequence alignment of members of the MglB_orphan1 clade and the MglB_coupled1 clade. Branches and ring colors identify the sequences from the MglB_orphan1 clade found in panel A (blue) and the MglB_coupled1 sequences that are genomically coupled to group 1 MglA (black). (C) Sequence logo corresponding to the clade composed entirely of coupled sequences and the clade composed of primarily orphan sequences (MglB_orphan1 sequences plus nine MglB_coupled1 sequences, as described in the text) were generated from the multiple-sequence alignment used in panel B that includes residues 15 to 129 of MglB (MXAN_1926) or residues 3 to 120 of MglC (MXAN_5770). Arrows below the orphan sequence logo indicate residues of MglC targeted for mutagenesis: F25, D26, and I28. In the logos, the letter size at each position represents the relative frequency of the given amino acid at that position.

In order to further understand the sequence differences underlying the primarily orphaned and coupled clades (Fig. 1B), we built sequence logos from the protein sequences of each clade. Comparisons between sequences from each clade revealed few conserved positions shared between the two groups (Fig. 1C). Overall, the orphan clade sequences show fewer conserved positions than the coupled clade sequences, which is consistent with the longer branch lengths between orphan clade members than those between coupled clade members (Fig. 1B). We identified a few key sequence attributes in each of the two groups that correlate with their group status (Fig. 1C). Both groups share an invariant glycine in the same position (corresponding to G27 in MglC and G39 in MglB). The orphan sequences have a conserved aspartate (corresponding to D26 in MglC) adjacent to the conserved glycine that is not conserved in the coupled sequences. Instead, there is a strongly conserved aspartate near but distinct from this position in the coupled sequences (corresponding to D36 in MglB from M. xanthus).

MglC is important for T4P-dependent motility and gliding motility.

Due to its homology with MglB and the cooccurrence of MglB_orphan1 sequences with members of the MglA_1 group, we hypothesized that MglC might play a role in motility or motility regulation in M. xanthus. To that end, we created an in-frame deletion mutant of mglC and tested the mutant for T4P-dependent and gliding motility. On a 0.5% agar medium that favors T4P-dependent motility (50), wild-type (WT) cells formed the long flares characteristic of T4P-dependent motility, while ΔmglC cells formed fewer flares that varied greatly in length, with some flares resembling those in WT and others being significantly shorter (Fig. 2A). On 1.5% agar medium, which favors gliding motility (50), the WT colony edge was irregular in the case of WT when viewed at low magnification, and, at higher magnification, individual cells characteristic of gliding motility were visible at the colony edge (Fig. 2B). Such irregular colony edges and individual cells were also present in colonies of ΔmglC cells. Additionally, these colonies contained swirls of cells (Fig. 2B, white arrowheads). Colonies of the ΔmglC mutant had 10.1 ± 2.8 swirls per colony (mean ± standard deviation) at 24 h, whereas WT colonies had significantly fewer of these swirls (1.2 ± 1.1 swirls per WT colony at 24 h) (P < 5 × 10−9). To more precisely quantify a potential defect in gliding motility in the ΔmglC cells, we measured colony expansion after 96 h. As shown in Fig. 2C, WT colonies spread significantly further over 96 h than ΔmglC colonies.

FIG 2.

MglC is important for regulation of T4P-dependent motility and gliding motility. Strains of the indicated genotypes were incubated on 0.5% agar–0.5% CTT plates (A) or 1.5% agar–0.5% CTT plates (B) for 24 h. Images within the black rectangle in panels A and B represent double mutants. In the ΔmglC mutant that is complemented by a WT copy of mglC, the complementing copy is expressed from the pilA promoter at the Mx8 attB site. Colonies on 1.5% agar–0.5% CTT plates were incubated for 96 h and imaged (C), and the colony diameter was measured (D). Bars represent the average diameter of at least four colonies, and error bars represent the standard deviation. *, P < 0.05 from a two-sample t test between WT and the indicated mutant. Scale bars represent 2 mm (A) or 100 μm (B). (D) MglC is necessary for timely reversals. Fifty representative cells of the indicated genotype were imaged at 30-s intervals for 15 min, and the number of reversals per cell were manually quantified and plotted. Dashed lines represent the mean, the solid lines represent the median, the boxes denote quartiles, whiskers indicate 10% and 90% quantiles, and circles represent outliers.

Because ΔmglC mutant cells were still motile by both T4P-dependent motility and gliding motility but showed reduced colony expansion, as previously described, for the hyperreversing ΔmglB and hyporeversing ΔfrzZ mutants, we tested whether MglC is involved in regulating the reversal frequency. To that end, we tracked individual cells by time-lapse microscopy and determined that ΔmglC cells reversed less frequently than WT cells, reversing a mean of 0.36 time in 15 min compared to 1.16 times in 15 min for WT cells (Fig. 2D).

To confirm that the motility defects in the ΔmglC mutant were caused by the lack of MglC, we created a plasmid for complementation experiments in which mglC was expressed from the ppilA promoter and integrated at the Mx8 attB site. The motility defects as well as the reversal defect were corrected by the ectopic expression of MglC (Fig. 2). We concluded that MglC is essential neither for T4P-dependent motility nor for gliding motility and that MglC is important for regulation of the reversal frequency.

MglC functions in the same pathway as MglA, MglB, RomR, and FrzZ.

To test whether MglC functions together with MglA, MglB, RomR, and FrzZ in the regulatory pathway that controls motility and reversals, we created double mutants with mutations in mglC and mglA, mglB, romR, or frzZ. Motility assays confirmed that cells that contained an in-frame deletion of mglA (ΔmglA) were deficient in T4P-dependent motility and gliding motility and that ΔromR, ΔmglB, and ΔfrzZ cells displayed a significant reduction in both T4P-dependent and gliding motility after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 2A and B). After 24 h of incubation, the motility phenotypes of the double mutants most closely resembled that of the single ΔmglA, ΔmglB, and ΔromR mutants (Fig. 2A and B), suggesting that these three genes are epistatic to mglC. Moreover, mglB is also epistatic to mglC in terms of reversal frequencies; the ΔmglB and ΔmglB ΔmglC mutants reversed on average 2.80 and 2.92 times in 15 min, respectively, which is hyperreversing compared with WT or the ΔmglC single mutant (Fig. 2D). The phenotypes of the ΔfrzZ, ΔmglC, and ΔfrzZ ΔmglC mutants were similar, which was expected since the ΔfrzZ and ΔmglC phenotypes are also similar (Fig. 2B). These data were also supported by detailed quantifications of spreading after 96 h by gliding motility (Fig. 2C). The ΔmglA and ΔmglA ΔmglC mutants both showed lack of spreading, with colonies remaining at the initial 0.5-cm diameter upon inoculation. The ΔmglB and ΔmglB ΔmglC mutants also spread a similar small amount. Although the ΔromR and ΔromR ΔmglC mutants exhibited the expected reduced colony spreading after 96 h, they showed a small but statistically significant difference in colony spreading at 96 h (P = 0.0012). This suggests that romR is not completely epistatic to mglC. Finally, the ΔfrzZ, ΔmglC, and ΔfrzZ ΔmglC mutants spread similarly and significantly less than WT but were not differentiable. Thus, excluding RomR, these data are in agreement with the epistasis analysis based on the 24-h time point. In total, these data suggest that MglC functions in the same pathway as MglA, MglB, RomR, and FrzZ.

As described, the ΔmglC mutant hyporeverses compared to WT. The ΔmglA and ΔromR mutants showed too little gliding motility to allow quantification of the reversal frequencies (24, 27). On the other hand, the ΔmglB mutant reverses more frequently than WT (24, 27) (Fig. 2D), and the ΔfrzZ mutant, similarly to the ΔmglC mutant, hyporeverses (51). We suggest that these reversal differences compound over time to create distinct gliding motility spreading distances over the course of 96 h. WT colonies spread significantly further over 96 h than colonies with mutations in any of the tested motility- and polarity-regulating genes. Furthermore, the hyperreversing ΔmglB mutant generated colonies that spread significantly less than the hyporeversing ΔfrzZ and ΔmglC mutants (Fig. 2C) (P < 0.05 with t test comparing ΔmglB mutant and each of the other strains, except for the ΔmglB ΔmglC double mutant). We conclude that MglC is not essential for motility but rather has a function in regulating the reversal frequency, and we suggest that MglC acts upstream of MglA and MglB and downstream of FrzZ in the regulation of motility, whereas the epistasis analysis is inconclusive in regard to the relationship between MglC and RomR. Also, MglC is functionally distinct from its paralog, MglB.

MglC is asymmetrically localized to the lagging cell pole.

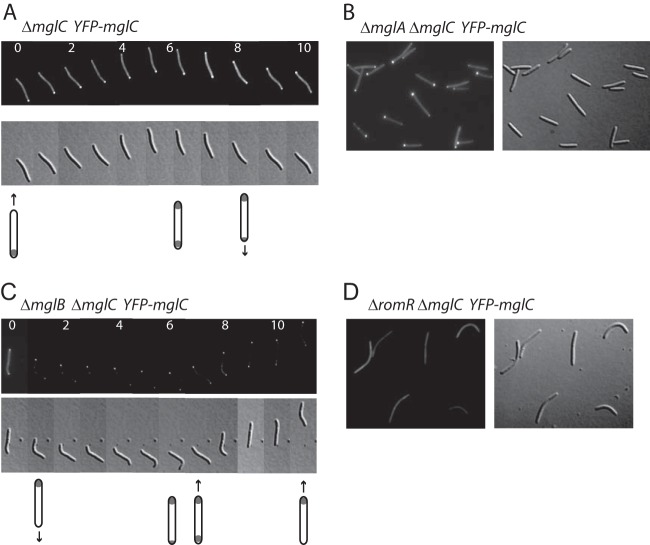

MglA, MglB, and RomR are all polarly localized. To determine the localization of MglC in moving cells, we expressed a functional and fully complementing copy of MglC fused to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) at its N terminus (YFP-MglC) from the Mx8 attB site in the ΔmglC mutant (data not shown). We then observed the localization of the fusion protein during cell movement by fluorescence microscopy. MglC was primarily located at the lagging cell pole in 96% of 50 motile cells and had a smaller distinct cluster at the leading cell pole in 10% of those cells (Fig. 3A). Moreover, in 38 of 40 reversals observed (95%), the localization of YFP-MglC changed so that, after a reversal, the large cluster was at the new lagging cell pole.

FIG 3.

Asymmetric polar localization of MglC depends on MglB and RomR. Cells from exponentially growing liquid cultures of the ΔmglC YFP-mglC, ΔmglA ΔmglC YFP-mglC, ΔmglB ΔmglC YFP-mglC, or ΔromR ΔmglC YFP-mglC strain were spotted onto TPM agar pads and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. (A and C) Dynamic localization of YFP-MglC in moving cells; individual images were captured every 30 s. Numbers indicate time in minutes, and the cartoons below indicate the fluorescence localization patterns and direction of cell movement. The cell in panel A reversed at 5 min, and the cell in panel C reversed at 6 min.

Next, we systematically determined whether MglB, RomR, or MglA affects the localization of MglC. In the absence of MglA, all cells were nonmotile, and 96 of 100 cells had a highly asymmetric YFP-MglC localization, with a cluster at only one cell pole (Fig. 3B). As these cells did not move, however, there was no leading or lagging cell pole.

In the ΔmglB mutant, of 50 individual moving cells, YFP-MglC was symmetrically bipolar in 50%, was primarily localized to the leading cell pole in 40% of cells, and was primarily localized to the lagging pole in 10% of cells, although this lagging pole localization pattern was the least stable over time (Fig. 3C). For many of the observed cells, the localization patterns changed over time between symmetric or asymmetric and also switched from lagging pole to leading pole localization, and this switching was not necessarily associated with cellular reversals (Fig. 3C). These data provide evidence that MglB influences the localization of MglC and that, while MglB is not important for polar localization of MglC, MglB is important for stably maintaining the primarily lagging cell pole localization of MglC. Interestingly, in the absence of MglB, MglA and RomR are also mostly symmetrically localized at the two cell poles (24–27).

In the ΔromR mutant cells, which were essentially nonmotile by gliding motility, YFP-MglC no longer showed polar localization; instead, YFP-MglC showed diffuse cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 3D). Similarly, MglA was diffusely localized in the absence of RomR, whereas MglB was mostly symmetrically localized at the two poles in the absence of RomR (24, 27). Thus, MglC is completely dependent on RomR for polar localization.

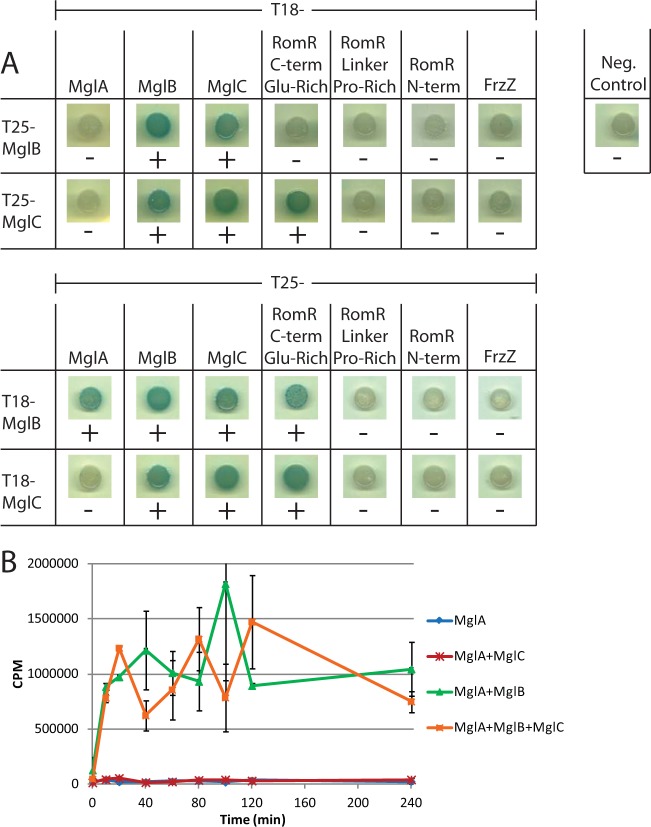

MglC directly interacts with MglB, RomR, and itself.

Given that the motility assays as well as the epistasis and localization results suggested that MglC is important for regulation of motility, we next sought to determine if MglC could directly interact with the other proteins that regulate motility. MglA and MglB are single-domain proteins, FrzZ consists of two receiver domains, and the RomR response regulator consists of a receiver domain and a C-terminal output domain. This output domain has been divided into two regions, a Pro-rich linker and a C-terminal Glu-rich region (24). Bacterial two-hybrid (BACTH) analysis revealed that MglC directly interacts with itself, MglB, and the C-terminal Glu-rich region of RomR, but we did not detect interactions with MglA, FrzZ, or the N-terminal receiver domain or Pro-rich linker domain of RomR (Fig. 4A). Importantly, in this assay, MglB, as expected, interacted with MglA, whereas no interaction was detected between MglC and MglA. These data support a model in which MglC acts to regulate motility by interacting directly with RomR and MglB.

FIG 4.

MglC interacts with itself, MglB, and the C-terminal Glu-rich region of RomR. (A) Full-length MglB, MglA, MglC, FrzZ, the C-terminal Glu-rich region of RomR, the Pro-rich linker of RomR, or the N-terminal receiver domain of RomR was fused to the indicated variant of the Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase and coexpressed in the indicated combinations in E. coli BTH101. The negative control demonstrates that there is no interaction between the T25 and T18 adenylate cyclase fragments in the absence of bait proteins. +, blue colonies and protein interactions; −, white colonies and no protein-protein interactions. (B) Purified MglC does not inhibit GAP activity of MglB and does not stimulate GTPase activity of MglA in vitro. In vitro GTPase assays were carried out as described previously (45) using 2 μM (each) indicated purified protein combinations. Aliquots of each reaction were sampled and quenched with activated charcoal at the indicated time points. Each data point represents the average of two separate experiments, except for MglA 20 min and MglA + MglB 20 min, which only represent one replicate. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Because ΔmglB and ΔmglC mutants have opposite reversal phenotypes (hyperreversing and hyporeversing, respectively [Fig. 2D]) and the two proteins interact, we hypothesized that MglC could act to inhibit the GAP activity of MglB on MglA. To this end, we purified His6-tagged soluble MglA, MglB, and MglC from E. coli and performed a GTPase assay in vitro. In short, we incubated the proteins with [γ-32P]GTP, collected samples after discrete periods of incubation, and measured the 32P freed by GTP hydrolysis in those samples. MglA had a low level of GTPase activity, which was stimulated when MglB was added in an equimolar amount to MglA (Fig. 4B). Adding an equimolar amount of MglC to MglA did not stimulate MglA GTPase activity. Similarly, addition of equimolar amounts of MglB, MglC, and MglA did not interfere with the GAP activity of MglB (Fig. 4B), nor did adding a 4-fold molar excess of MglC in comparison to MglA and MglB (data not shown). Thus, MglC does not appear to regulate motility by directly altering the GTPase activity of MglA or by reducing the GAP activity of MglB.

The MglC FDI surface is necessary for interaction with MglB and for proper function.

The structures of Thermus thermophilus MglB alone and complexed with MglA-GppNHp have been solved (31). MglB alone as well as in the complex with MglA forms a dimer in which each protomer adopts a Roadblock/LC7 fold. MglB and MglC of M. xanthus have little primary sequence homology, with 8%/17% identity/similarity. We performed a structural analysis of MglC using the Phyre2 fold prediction server (38) and found that MglC is predicted to have a Roadblock/LC7 fold similar to the crystallized MglB homologs from T. thermophilus and Streptomyces avermitilis. These predictions suggest that, despite primary sequence divergence, MglC and MglB of M. xanthus may have significant similarity in their tertiary and quarternary structures and that MglC forms a dimer (Fig. 5A).

FIG 5.

The FDI surface of MglC is necessary for MglB interaction and function in vivo. (A) A structural model of an MglC dimer based on the MglB structures from T. thermophilus and S. avermitilis. Substituted residues on the FDI surface are highlighted in red. (B) MglCF25A D26A I28A interacts less efficiently with MglB than the MglC WT protein. BACTH analyses were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 4A. (C) MglCF25A D26A I28A does not complement the ΔmglC mutant. Motility assays on 0.5% agar, favoring T4P-dependent motility, and on 1.5% agar, favoring gliding motility, were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2A and B. (D) YFP-MglCF25A D26A I28A shows aberrant localization. Cells were imaged as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

We hypothesized that the surface region in MglC, which corresponds to the surface region in MglB that interacts with MglA, could be involved in the interaction with MglB and/or RomR. To test this hypothesis, we first superimposed a structural model of MglC onto the structure of the MglA-GppNHp/MglB complex. From this superimposed structure, we identified three amino acids (F25, D26, and I28) that are within 5 Å of MglA in the MglA-GppNHp/MglB complex and that are unlikely to be essential for either dimerization or proper folding of MglC (Fig. 5A). Of these residues, D26 is highly conserved in MglB_orphan1 proteins; however, F25 and I28 are not (Fig. 1C, arrows).

To test this surface, which we refer to as the FDI surface due to the substituted amino acid residues, for a possible role in protein-protein interactions and function, we created a triple-substitution mutant replacing F25, D26, and I28 in MglC with alanines (MglCF25A D26A I28A). The FDI surface substitutions did not affect the interaction between MglCF25A D26A I28A and a WT variant of MglC in BACTH analyses (Fig. 5B). Next, we tested the ability of MglCF25A D26A I28A to interact with MglB and the C-terminal domain of RomR. MglCF25A D26A I28A did not show reduced interaction with RomR, suggesting that this interaction probably involves a different region on the MglC surface. Interestingly, MglCF25A D26A I28A was unable to interact with MglB, suggesting that this surface is necessary for the MglB/MglC interaction (Fig. 5B).

To assess the importance of the reduced interaction between MglB and the MglCF25A D26A I28A variant, we next attempted to complement the ΔmglC mutant with MglCF25A D26A I28A or with YFP-tagged MglCF25A D26A I28A. Complementation with WT MglC was complete, as is complementation with a YFP-tagged variant of MglC (Fig. 2 and 5C and data not shown). In contrast, MglCF25A D26A I28A was unable to restore T4P-dependent and gliding motility in the ΔmglC mutant, and these defects were both visible after 24 h (Fig. 2C) and could be quantified in the ultimate colony size after 96 h of gliding motility (Fig. 5C).

We next examined the role of the FDI surface in MglC localization. YFP-MglCF25AD26A I28A still showed polar localization but was preferentially located at the leading cell pole (Fig. 5D), in contrast to the WT MglC protein that preferentially localized to the lagging cell pole. Thus, the FDI surface is necessary for proper MglC localization and function. Interestingly, the leading pole localization pattern of the FDI surface mutant was similar to the predominant localization pattern of WT MglC in the absence of MglB (Fig. 3C), although, instead of occurring in 40% of cells, 100% of cells showed leading pole localization in the case of YFP-MglCF25A D26A I28A. We conclude that the FDI surface is necessary for the interaction between MglB and MglC; however, given the altered frequencies of bipolar and leading pole localization, this surface may also influence MglC localization in an MglB-independent manner.

DISCUSSION

Gene duplication followed by neo- or subfunctionalization is a common paradigm for the evolution of novel proteins and, in that way, novel protein functions (52–56). Here, we demonstrated that MglC, which is a paralog of MglB, the cognate GAP of MglA, is involved in regulating motility in M. xanthus. Surprisingly, although these two paralogs interact directly and act in the same pathway to regulate cell polarity and motility, their functional roles have diverged, and they now play opposite roles. MglB is important neither for T4P-dependent motility nor for gliding motility, but it is essential for continued movement in a given direction by stimulating the disassembly of motility complexes at the lagging cell pole and, thus, suppressing reversals (1, 10, 23, 25, 26). Similarly, MglC is not important for T4P-dependent motility or for gliding motility; however, MglC is important for cellular reversals. Interestingly, the small GTPase SofG is an orphan MglA paralog and plays a divergent role in regulating T4P-dependent motility compared to its paralog, MglA (33, 49). We hypothesize that these examples of gene duplication followed by functional divergence have evolved to allow M. xanthus to more finely regulate the important cellular process of motility.

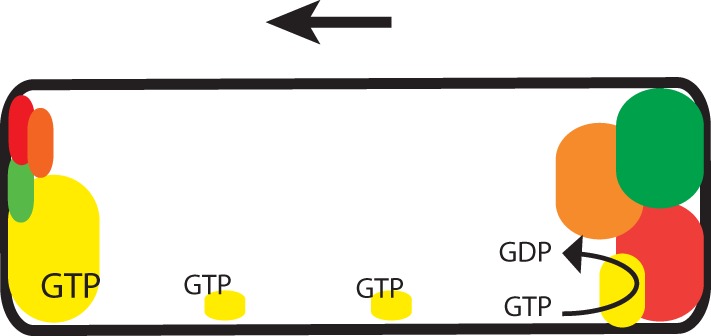

MglA, MglB, and RomR all interact directly with each other, while we detected interactions only between MglC and MglB and RomR, and no interactions were detected between MglC and MglA. Accordingly, we were unable to detect an effect of MglC on the GTPase activity of MglA in vitro. Also, we did not find evidence that MglC inhibits the GAP activity of MglB in vitro. In the current model for regulation of the polarity of the motility systems in M. xanthus, RomR recruits MglA-GTP to the cell poles, while MglB at the lagging cell pole is important for establishing the MglA-GTP asymmetry by means of its GAP activity. Ultimately, these interactions result in the formation of MglA/RomR and MglB/RomR complexes at the leading and lagging cell pole, respectively, although the process initiating this asymmetry is still under investigation (Fig. 6). The cytological data and data from direct interaction analyses presented here suggest that MglC is also recruited to the poles in an asymmetric fashion by RomR (Fig. 6). MglC also interacts directly with MglB; however, this interaction is not sufficient for polar localization of MglC, because MglC is diffusely localized in the absence of RomR. In the absence of MglB, RomR localization is biased toward a more bipolar symmetric pattern (24, 27). Thus, we hypothesize that the more bipolar symmetric localization pattern of MglC in the absence of MglB is explained by the effect of MglB on RomR localization. Moreover, we suggest that MglC switches polarity during a reversal by following RomR.

FIG 6.

Model of regulation of motility polarity in M. xanthus. Schematic of protein localization in a cell moving in the direction indicated by the arrow. The size of the colored regions corresponds to the relative amounts of protein at the indicated pole or cellular location. Yellow, MglA; red, MglB; green, RomR; orange, MglC. The small clusters of MglA-GTP along the cell length indicate MglA-GTP associated with gliding motility complexes.

The ΔmglC mutant largely phenocopies a ΔfrzZ mutant, i.e., both mutants show reduced T4P-dependent motility and gliding motility in colony expansion assays, and both mutants hyporeverse. Therefore, we suggest that the primary function of MglC, similarly to FrzZ, is in regulating reversals. According to current models, cellular reversals are induced by signaling of the Frz chemosensory system leading to FrzZ phosphorylation. By an unknown mechanism, FrzZ phosphorylation is hypothesized to result in RomR phosphorylation, which causes the release and subsequent relocation of MglA, MglB, RomR, and MglC to opposite cell poles. Because the ΔmglC mutant hyporeverses, we suggest that MglC is important for one or more of these processes. How MglC functions to regulate cellular reversals remains to be deciphered. However, on the basis of the data presented here, we suggest that MglC, by interacting with RomR and MglB, either functions between FrzZ and RomR or between RomR and MglB to stimulate reversals. Future work will be aimed at identifying the mechanism of MglC function in regulating cellular reversals.

Gene duplication followed by functional divergence is a common paradigm for evolution of novel genes and novel functions (52–56). To our knowledge, MglC is unique in that it has apparently lost its ability to bind to MglA as well as its GAP activity against MglA but is still able to interact with some of the same proteins, has the same localization pattern, and is expressed under the same conditions as its paralog, MglB. Given the frequency of paralogous orphaned copies of this GAP in bacterial genomes, MglC may represent an important paradigm of gene duplication and divergence, in which a protein maintains the expression pattern and many of the protein-protein interactions of its ancestor while taking on a new regulatory function. MglC represents an important elaboration in the control of Ras-like GTPases and of complex biological processes like cellular motility.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank T. Mignot for plasmids pTM1 and pTM2 and J. Shrout for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a long-term postdoctoral fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation to A.L.M., by the German Research Council within the framework of the German-Israeli Project Cooperation Spatial and Temporal Regulation of Macromolecular Complex Formation in Bacteria, and by the Max Planck Society.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00548-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang Y, Ducret A, Shaevitz J, Mignot T. 2012. From individual cell motility to collective behaviors: insights from a prokaryote, Myxococcus xanthus. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36:149–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodgkin J, Kaiser D. 1979. Genetics of gliding motility in Myxococcus xanthus (Myxobacterales): two gene systems control movement. Mol Gen Genet 171:177–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00270004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu SS, Kaiser D. 1995. Genetic and functional evidence that Type IV pili are required for social gliding motility in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol 18:547–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser D. 1979. Social gliding is correlated with the presence of pili in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76:5952–5956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mignot T, Shaevitz JW, Hartzell PL, Zusman DR. 2007. Evidence that focal adhesion complexes power bacterial gliding motility. Science 315:853–856. doi: 10.1126/science.1137223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nan B, Mauriello EM, Sun IH, Wong A, Zusman DR. 2010. A multiprotein complex from Myxococcus xanthus required for bacterial gliding motility. Mol Microbiol 76:1539–1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun M, Wartel M, Cascales E, Shaevitz JW, Mignot T. 2011. Motor-driven intracellular transport powers bacterial gliding motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:7559–7564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101101108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balagam R, Litwin DB, Czerwinski F, Sun M, Kaplan HB, Shaevitz JW, Igoshin OA. 2014. Myxococcus xanthus gliding motors are elastically coupled to the substrate as predicted by the focal adhesion model of gliding motility. PLoS Comput Biol 10:e1003619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luciano J, Agrebi R, Le Gall AV, Wartel M, Fiegna F, Ducret A, Brochier-Armanet C, Mignot T. 2011. Emergence and modular evolution of a novel motility machinery in bacteria. PLoS Genet 7:e1002268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treuner-Lange T, Macia E, Guzzo M, Hot E, Faure L, Jakobczak B, Espinos L, Alcor D, Ducret A, Keilberg D, Castaing JP, Gervais SL, Franco M, Søgaard-Andersen L, Mignot T. 2015. The small G-protein MglA connects to the MreB actin cytoskeleton at bacterial focal adhesions. J Cell Biol 210:243–256. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201412047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jakobczak B, Keilberg D, Wuichet K, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2015. Contact- and protein transfer-dependent stimulation of assembly of the gliding motility machinery in Myxococcus xanthus. PLoS Genet 11:e1005341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ducret A, Fleuchot B, Bergam P, Mignot T. 2013. Direct live imaging of cell-cell protein transfer by transient outer membrane fusion in Myxococcus xanthus. eLife 2:e00868. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nan B, Chen J, Neu JC, Berry RM, Oster G, Zusman DR. 2011. Myxobacteria gliding motility requires cytoskeleton rotation powered by proton motive force. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:2498–2503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018556108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nan BY, Bandaria JN, Moghtaderi A, Sun IH, Yildiz A, Zusman DR. 2013. Flagella stator homologs function as motors for myxobacterial gliding motility by moving in helical trajectories. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E1508–E1513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219982110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackhart BD, Zusman DR. 1985. Frizzy genes of Myxococcus xanthus are involved in control of frequency of reversal of gliding motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82:8767–8770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sager B, Kaiser D. 1994. Intercellular C-signaling and the traveling waves of Myxococcus. Genes Dev 8:2793–2804. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.23.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berleman JE, Scott J, Chumley T, Kirby JR. 2008. Predataxis behavior in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:17127–17132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804387105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulyha I, Schmidt C, Lenz P, Jakovljevic V, Höne A, Maier B, Hoppert M, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2009. Regulation of the type IV pili molecular machine by dynamic localization of two motor proteins. Mol Microbiol 74:691–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06891.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mignot T, Merlie JP, Zusman DR. 2005. Regulated pole-to-pole oscillations of a bacterial gliding motility protein. Science 310:855–857. doi: 10.1126/science.1119052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedrich C, Bulyha I, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2014. Outside-in assembly pathway of the type IV pilus system in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol 196:378–390. doi: 10.1128/JB.01094-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zusman DR, Scott AE, Yang Z, Kirby JR. 2007. Chemosensory pathways, motility, and development in Myxococcus xanthus. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:862–872. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2004. Making sense of it all: bacterial chemotaxis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:1024–1037. doi: 10.1038/nrm1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keilberg D, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2014. Regulation of bacterial bell polarity by small GTPases. Biochemistry 53:1899–1907. doi: 10.1021/bi500141f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keilberg D, Wuichet K, Drescher F, Sogaard-Andersen L. 2012. A response regulator interfaces between the Frz chemosensory system and the MglA/MglB GTPase/GAP module to regulate polarity in Myxococcus xanthus. PLoS Genet 8:e1002951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonardy S, Miertzschke M, Bulyha I, Sperling E, Wittinghofer A, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2010. Regulation of dynamic polarity switching in bacteria by a Ras-like G-protein and its cognate GAP. EMBO J 29:2276–2289. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Franco M, Ducret A, Mignot T. 2010. A bacterial Ras-like small GTP-binding protein and its cognate GAP establish a dynamic spatial polarity axis to control directed motility. PLoS Biol 8:e1000430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Guzzo M, Ducret A, Li YZ, Mignot T. 2012. A dynamic response regulator protein modulates G-protein-dependent polarity in the bacterium Myxococcus xanthus. PLoS Genet 8:e1002872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patryn J, Allen K, Dziewanowska K, Otto R, Hartzell PL. 2010. Localization of MglA, an essential gliding motility protein in Myxococcus xanthus. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 67:322–337. doi: 10.1002/cm.20447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nan B, Bandaria JN, Guo KY, Fan X, Moghtaderi A, Yildiz A, Zusman DR. 2015. The polarity of myxobacterial gliding is regulated by direct interactions between the gliding motors and the Ras homolog MglA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E186–E193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421073112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonardy S, Freymark G, Hebener S, Ellehauge E, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2007. Coupling of protein localization and cell movements by a dynamically localized response regulator in Myxococcus xanthus. EMBO J 26:4433–4444. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miertzschke M, Koerner C, Vetter IR, Keilberg D, Hot E, Leonardy S, Søgaard-Andersen L, Wittinghofer A. 2011. Structural analysis of the Ras-like G protein MglA and its cognate GAP MglB and implications for bacterial polarity. EMBO J 30:4185–4197. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mauriello EMF, Mouhamar F, Nan B, Ducret A, Dai D, Zusman DR, Mignot T. 2010. Bacterial motility complexes require the actin-like protein, MreB, and the Ras homologue, MglA. EMBO J 29:315–326. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulyha I, Lindow S, Lin L, Bolte K, Wuichet K, Kahnt J, van der Does C, Thanbichler Søgaard-Andersen L. 2013. Two small GTPases act in concert with the bactofilin cytoskeleton to regulate dynamic bacterial cell polarity. Dev Cell 25:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T. 2005. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res 33:511–518. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. 2009. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol 26:1641–1650. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Letunic I, Bork P. 2007. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics 23:127–128. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. 2004. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res 14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. 2009. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc 4:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Julien B, Kaiser AD, Garza A. 2000. Spatial control of cell differentiation in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:9098–9103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jakovljevic V, Leonardy S, Hoppert M, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2008. PilB and PilT are ATPases acting antagonistically in type IV pili function in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol 190:2411–2421. doi: 10.1128/JB.01793-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karimova G, Pidoux J, Ullmann A, Ladant D. 1998. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:5752–5756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodgkin J, Kaiser D. 1977. Cell-to-cell stimulation of movement in nonmotile mutants of Myxococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 74:2938–2942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi X, Wegener-Feldbrugge S, Huntley S, Hamann N, Hedderich R, Sogaard-Andersen L. 2008. Bioinformatics and experimental analysis of proteins of two-component systems in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol 190:613–624. doi: 10.1128/JB.01502-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li SF, Shimkets LJ. 1988. Site-specific integration and expression of a developmental promoter in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol 170:5552–5556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stellwag E, Fink JM, Zissler J. 1985. Physical characterization of the genome of the Myxococcus xanthus bacteriophage Mx-8. Mol Gen Genet 199:123–132. doi: 10.1007/BF00327521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brinkmann T, Daumke O, Herbrand U, Kuhlmann D, Stege P, Ahmadian MR, Wittinghofer A. 2002. Rap-specific GTPase activating protein follows an alternative mechanism. J Biol Chem 277:12525–12531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wuichet K, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2015. Evolution and diversity of the Ras superfamily of small GTPases in prokaryotes. Genome Biol Evol 7:57–70. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi W, Zusman DR. 1993. The two motility systems of Myxococcus xanthus show different selective advantages on various surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:3378–3382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inclán YF, Vlamakis HC, Zusman DR. 2007. FrzZ, a dual CheY-like response regulator, functions as an output for the Frz chemosensory pathway of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol 65:90–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glasauer SM, Neuhauss SC. 2014. Whole-genome duplication in teleost fishes and its evolutionary consequences. Mol Genet Genomics 289:1045–1060. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0889-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scannell DR, Wolfe KH. 2008. A burst of protein sequence evolution and a prolonged period of asymmetric evolution follow gene duplication in yeast. Genome Res 18:137–147. doi: 10.1101/gr.6341207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lynch M, Conery JS. 2000. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science 290:1151–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salazar ME, Laub MT. 2015. Temporal and evolutionary dynamics of two-component signaling pathways. Curr Opin Microbiol 24:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alm E, Huang K, Arkin A. 2006. The evolution of two-component systems in bacteria reveals different strategies for niche adaptation. PLoS Comput Biol 2:e143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.